1. Introduction

In 2004, Democratic Governor Philip Bredesen of Tennessee announced a plan to reform TennCare, the state’s Medicaid program. The reform package proposed to remove 323,000 adults from TennCare/Medicaid including a large number of African Americans, and benefit reductions to another 400,000 adult enrollees who still remained in the program. Taken together, the disenrollment plan and benefit reductions represented the most drastic cuts to Medicaid since its creation in 1965.

The governor’s reform package ignited a political battle that lasted several years. Health care advocates, civil rights groups, and TennCare beneficiaries rallied against the plan. They organized town hall meetings, protests, and a 77-day sit-in at the governor’s office in the Spring 2005. Despite the political struggle, a scaled down version of the plan was approved by the Tennessee General Assembly in 2005. The final plan targeted 226,000 beneficiaries for disenrollment and hundreds of thousands of enrollees for benefit reductions with more cuts expected after the legislative session.

In addition, the reform package altered the guidelines for how beneficiaries could appeal their disenrollment from TennCare. The new rules mandated that beneficiaries seeking to appeal their disenrollment had to complete a seven-page appeals form that was reviewed by administrative hearing examiners. The appeals application, advocates argued, was too complex and burdened with medical terminology that was difficult to interpret for even experienced health care professionals. The governor, with support from state lawmakers, also shifted the appellate hearings from the Tennessee Department of State to the Department of Human Services. Whereas the Department of State had an established group of administrative law judges, the Department of Human Services hired 95 temporary hearing examiners and placed them in charge of the TennCare appeal proceedings [

1,

2]. Health care advocates believed this change was designed to minimize the rate of successful appeals.

This study examines how race and policy backlash—that is the backlash against Medicaid expansion—influenced the appellate process for beneficiaries disenrolled from the program. The main argument is that race—especially the predisposition of African Americans—influenced the outcome of the appellate proceedings. African Americans (or those living in communities heavily populated by African Americans) were adversely and disproportionately affected by the appellate process. This was partially due to attempts by lawmakers to avoid a backlash among rural (and mostly) white residents who were isolated from comprehensive health centers, and because it was much more politically palatable given the persistence of racial polarization in the state.

The theoretical framework advanced in this study explains how procedural deliberations (legal decisions, policy disputes, administrative hearings) exacerbate disparities and produce differential outcomes that correspond with racial and other ascriptive hierarchies. These differential outcomes occur at various stages of policy development: formulation, implementation, rule changes to existing policies, enforcement, and administrative review [

3,

4,

5]. Overall, the theoretical framework underscores how lawmakers can rearrange social policies such that they can intentionally or unintentionally exclude historically disadvantaged groups. In this study, special attention is given to appellate proceedings in a state bureaucracy that adjudicates the eligibility status of Medicaid recipients.

The data for this study were obtained through an Open Records Requests with the Tennessee Department of Human Services in compliance with state law.

1 The dataset encompasses more than 60,000 TennCare beneficiaries including 8000 African Americans who appealed their disenrolled from the program. It is the only comprehensive repository that matches TennCare beneficiaries by race, residence, and the finality decisions of the administrative hearing examiners. The study is buttressed by archival documents of the TennCare policy debate obtained from the TennCare Saves Lives Coalition (TCSLC), the leading advocacy group opposing the reform measures from 2004–2006.

Analyzing these data with logistic regression reveals the relationship between race and appellate proceedings. African Americans were treated unfairly in the early stage of the appellate process and those from racially polarized voting areas were less likely to receive fair rulings by hearing examiners. Additional findings identified age-related disparities between younger and older appellants, as well as a regional disadvantage between rural and urban beneficiaries in the appellate proceedings.

The first part of this study lays out a theoretical framework for evaluating how procedural disadvantages, hidden biases, and political signaling inform administrative law decisions. This is followed by a closer examination of the controversies involving TennCare policy in the state. Finally, drawing from the TennCare dataset, this study examines the differential outcomes found in the TennCare appellate proceedings.

2. Differential Policy and Procedural Outcomes

This research evaluates how legal and policy decisions deliberated in state bureaucracy—what is sometimes referred to as the “black box” of government—reinforce hierarchies that are especially disadvantageous to African Americans [

6,

7]. The framework guiding this study,

Differential Policy and Procedural Outcomes (DPPO), suggests that procedural decisions produce distinctive outcomes for historically disadvantaged communities and are shaped by hidden and racial biases. These biases may not be motivated by intentional racial animus, but are the consequence of power struggles over which groups and communities will benefit from public policies.

2.1. Procedural Disadvantage and Administrative Hearings

The research on procedural justice helps to inform this discussion of biases. The concept of procedural justice has its origins in John Rawls’ classic study, Theory of Justice [

8] in which he argues that a “veil of ignorance” should inform public deliberations in the policy and legal arenas. The veil of ignorance proposes that decision-makers (e.g., judges, hearing examiners, policymakers, etc.) should make decisions with little or no knowledge of the disputants’ personal characteristics, socio-demographic backgrounds, political affiliations, and other factors that can potentially bias their decisions.

The veil of ignorance builds procedural safeguards into the initial stage of the decision-making process. It forces decision-makers to deliberate without considerations of their own long-standing biases such as race, class, or political affiliations [

9]. The veil of ignorance is supposed to yield fairer outcomes such as civil liberty protections and the reduction of social and economic inequalities for the “least advantaged members of society” ([

8], p. 13). Without the veil of ignorance, racial, gender, and other identity-based biases can overwhelm deliberative proceedings. When decision-makers are in front of the veil of ignorance—when they have information about the personal characteristics and socio-demographic backgrounds of disputants—then they are more likely to make decisions that are unfair to members of historically disadvantaged communities.

Later, the study examines TennCare beneficiaries who were disenrolled from the program in 2005 and 2006. The individuals were allowed to appeal their disenrollment before a hearing examiner under the supervision of a state agency. This process reflects the “single investigator model” in “which hearing examiners are commissioned to investigate particular disputes” ([

10], p. 1274). It is one of the least preferred conflict resolution models for historically disadvantaged groups because hearing examiners are privy to the appellants’ racial, gender, and other socio-demographic backgrounds. In other words, the single-investigator model can cause a procedural backlash because hearing examiners can make decisions in front of the veil of ignorance.

Yet procedural justice is not only a dyadic process that involves hearing examiners and appellants. In a polarizing political environment, perceptions of impartiality are likely to persist regardless of whether decision-makers operate behind or in front of the veil of ignorance ([

11], pp. 128–30). These officials can alter the rules or procedures of legal or administrative hearings before they take place in order to pre-determine the outcome of the process ([

12], pp. 416–17). Governments that have preexisting administrative arrangements that promote fairness or distributive measures are more likely to be more responsive to disadvantaged groups during periods of crises ([

13], p. 604). On the other hand, in political environments where distributive measures have garnered the least support, procedural processes can produce a backlash that positions policies and administrative decisions against the disadvantaged.

2.2. Hidden Biases and Administrative Law

The discussion of procedural justice is useful for understanding how and why some participants believe that administrative hearings and other judicial proceedings are biased against them. Theories of administrative law decisions generally focus on the fairness of the decisions and whether biases shape the opinions of administrative law judges (ALJs) or hearing examiners ([

14,

15]; [

16], p. 1521). How these biases emerge is worthy of extensive discussion.

AJLs often have to resolve disputes involving social policies. These policies are typically shaped by social constructions of which some groups are considered more deserving recipients ([

17], p. 335). This social construction can designate deserving/underserving recipients based upon distinct characteristics such as race, social class, and age. It can also use negative stereotypes to distinguish between underserving and deserving beneficiaries.

In many cases, biases are embedded in the structure of the administrative review proceedings and policymaking process [

18]. Even redistributive policies are shaped by ascriptive hierarchies as lawmakers tend to incorporate the preferences of their key constituency groups into the framework of these policies. For example, the New Deal was a far reaching set of initiatives that was supported by African Americans and civil rights groups in the 1930s. Yet, it produced differential outcomes for blacks and whites. Katznelson [

19] contends that New Deal policies amounted to an affirmative action program for whites, because they were crafted as a compromise between President Franklin D. Roosevelt and southern lawmakers intent on preserving state autonomy. Northern blacks in industrial centers also obtained more emergency health services than southern blacks living in de jure segregated environments during this period ([

19], pp. 37–38). These sentiments were echoed in Mettler’s [

20] examination of women and the New Deal. She discovered that white men represented by male-dominated labor groups and southern lawmakers were the primary beneficiaries of New Deal policies compared to women and blacks.

Race is a predictable variable that explains both racial inclusion and marginalization in administrative hearing proceedings. In housing discrimination cases, hearing examiners are more likely to decide in favor of African Americans compared to other marginalized groups such as persons with mental health disabilities or recovering addicts seeking access to affordable housing ([

21], p. 370). This is because the law was originally shaped by a civil rights framework that embedded the preferences of influential civil rights groups. These preferences were then institutionalized in the bureaucratic machinery of the executive branch.

Furthermore, race may be conditioned by regional differences that complicate the administrative adjudication process [

22]. Lens and Vorsanger ([

23], p. 446) found regional disparities regarding welfare recipients who appealed their disenrollment. Appellants in the North were disproportionately located in urban communities compared to those from the South. The authors found that New York City’s climate of social activism may have increased the rate of successful appeals in the city compared to rural communities across the state.

2.3. Political Signaling and Public Salience

Some research studies found that procedural disputes are influenced by the broader political environment even though they are supposed to be independent of politics [

15,

24]. Elected officials, lobbyists, and grassroots coalitions engage in what social scientists call ‘political signaling’ to distinguish publicly salient policies from less significant issues ([

25]; [

7], p. 144]). The Supreme Court, for example, may decide to hear a case based on the agenda-setting priorities of lawmakers or the executive branch [

26]. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 is an example of a publicly salient issue in which various political coalitions attempted to shape the Supreme Court’s position through signaling.

For various reasons, publicly salient issues achieve prominence in a competitive political arena. They may cause confusion or require interpretation by the courts, or they may be so polarizing that the judicial branch must intervene to resolve the disputes. Lawmakers may also shape the direction of administrative law decisions through ex post reviews ([

27], p. 310). Once a law has been implemented or rule changes are made to existing statutes, lawmakers may intervene through oversight, supervision, or by creating new guidelines for policy implementation. These ex post reviews can provide cues or signals for how bureaucrats, the courts, and ALJs should interpret the law or appellate decisions.

Political signaling raises several concerns about the fairness of the administrative legal process during political battles [

28]. An administrative legal process that is shaped during the ex ante stage of a policy dispute or one that is predicated by political motives may send a signal to ALJs about how they should adjudicate appeals. If appellants feel that the motives of adjudicators are partial to certain groups, then they will interpret the outcomes as unfair ([

29], p. 90; [

30], p. 485; [

31], pp. 127–28).

Political signaling raises the question of the autonomy of ALJs, hearing examiners, and quasi-independent institutions inside the executive branch or state bureaucracy. Though not related to Medicaid policy, King-Meadows [

32] outlines how the U.S. Justice Department’s Voting Rights Section was reorganized under President George W. Bush (2001–2009). The Bush administration replaced long-time civil rights attorneys with political appointees, who attempted to redesign the rules for assessing voting rights claims from local jurisdictions.

Social movements and grassroots advocacy coalitions also engage in political signaling [

33]. Grassroots coalitions may shape the administrative law process with the understanding that lawmakers may make changes to it through ex post oversight. They may also mobilize dissent in order educate AJLs or hearing examiners about hidden biases in the appeal hearings. Rachlinski et al. ([

34], p. 1221) found that despite the racial biases entrenched in the administrative legal process, judges are more likely to police their behavior once they became aware of the racialized impact of their decisions.

In addition, grassroots coalitions can promote the distinct concerns of vulnerable constituency groups in order to win over lawmakers who are undecided on how they will vote on a critical issue. However, even grassroots coalitions will prioritize some constituency groups over others in order to win over undecided lawmakers and swing voters [

35]. At times, grassroots coalitions may be divided over which groups to present as the best examples for mobilizing public sentiment in support of a policy.

Accordingly, political signaling is important because it highlights publicly salient issues and attempts to coerce, directly or indirectly, the decision-making processes of the courts and quasi-independent agencies. Within a given debate, political signaling is not monotholic, but is carried out by political elites and grassroots coalitions, and divisions exist within both elite and grassroots coalitions about what constituency groups will benefit from statutory and administrative decisions.

The previous discussion highlights how procedural disadvantage, hidden biases, and political signaling can produce differential outcomes in the black box of government. Regarding the TennCare appeals, the appellate proceedings for TennCare built in a procedural disadvantage for historically disadvantaged groups. The hearing examiners had to make decisions under political duress and during a time when the governor and state lawmakers aggressively moved to downsize the program. Furthermore, the hearing examiners were mostly inexperienced in administrative proceedings and were privy to the socio-demographic characteristics of the appellants.

The concerns about political signaling converge with the discussion about hidden biases and procedural disadvantage. If policymakers are conditioned by group reputations such as stereotypes about low-income constituents, then they are likely to shape policy and procedural outcomes that benefit groups or social categories with good reputations. Political signaling can further enhance a group’s influence or disadvantage members of a group that presumably has a bad reputation. This signaling gives ALJs or hearing examiners a template for evaluating constituency groups.

The theoretical framework underscores several hypotheses that are evaluated in the remainder of the study. The first hypothesis is that appellate proceedings will produce racially disparate outcomes for blacks compared to whites. The second hypothesis suggests that beneficiaries from rural jurisdictions will receive more favorable decisions than those living in urban communities. This is because the governor and state lawmakers focused intentionally on the protecting the status of rural beneficiaries compared to those living in urban communities where there existed an extensive array of safety-net medical facilities. Furthermore, because both the governor and health care advocates were attempting to sway median voters and lawmakers, many of whom lived in rural communities, their constituents were targeted much more than urban communities. The third hypothesis suggests that the beneficiaries who lived in target counties or counties that experienced heightened levels of mobilization by grassroots activists were more likely to receive favorable administrative hearings. These mobilization activities, it can be argued, influenced the broader political environment and sent signals to hearing examiners that residents from their respective counties should receive fair hearings.

3. TennCare: A Case Study of Tennessee’s Medicaid Program

TennCare was created in 1994 as an expanded Medicaid program by Democratic Governor Ned McWherter. The governor was attracted to the expansion because it allowed the state to receive federal dollars as part of a two to one matching fund. For every one dollar Tennessee spent on the program, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) provided a two-dollar match.

The creation of TennCare provided health care access to groups historically excluded from traditional Medicaid coverage [

36]. This coverage encompassed hundreds of thousands of uninsured residents and others suffering from chronic diseases, as well as senior citizens whose prescription drug costs were not entirely covered by Medicare. Health care advocates further believed TennCare would encourage providers to invest in preventive care, as well as give medically needy and working-poor consumers access to better hospital care.

TennCare operated as a government-administered managed care program that converted health care providers and insurance companies into managed care organizations. Under this framework, providers would receive lump sums of money or capitated fees to deliver health care to thousands of patients ([

36], p. 23; [

37]). TennCare advocates insisted that the fee caps would coerce insurers to take a more aggressive posture in managing the health care of their patients. This meant, under the best case scenario, that insurers would pour resources into prevention strategies in order to mitigate risk behaviors. The focus on prevention intended to preempt the onset of chronic illnesses that were exacerbated by beneficiaries’ inattention to doctors’ visits.

Interestingly, TennCare was similar to the privately-administered health management organization (HMO) system of health care delivery. Yet ironically, the program was created during the height of the managed care backlash against private insurers ([

38], p. 62). The backlash against managed care consisted of “negative media coverage, repeated atrocity-type anecdotes, and bashing by politicians,” all of which was shaped by the belief that HMOs forced Americans to ration their health care ([

39], p. 37). In the case of TennCare, insurance companies and fiscal conservatives believed the program cost too much money and harmed the state budget considering that Tennessee had no state income tax to replenish its revenues.

After McWherter’s departure, Republican Governor Don Sundquist altered TennCare’s funding formula. He changed its traditional managed care framework of the program by shifting the costs from insurance companies and to the state. Tennessee elected Bredesen as the new governor in 2002, who, as a fiscally-conservative Democrat and former health care executive, promised to fix TennCare’s management and funding problems. Though he was ambiguous about what this fix entailed, he eventually decided on a massive overhaul of the program that disenrolled hundreds of thousands of beneficiaries and reduced benefits to the remaining recipients.

In response to this policy backlash, health care advocates lead a two-year campaign against the governor’s reform package [

40,

41]. From 2004–2006, they organized dozens of series of town halls, protests, and trainings to counter the governor’s proposal [

42]. Many of these actions occurred in targeted districts with large numbers of swing voters and TennCare beneficiaries.

Blacks were particularly critical of the Medicaid reforms. In the spring 2005, nearly 80% of blacks compared to 45% of whites expressed opposition to the Medicaid cuts [

43]. Civil rights groups such as the NAACP, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the Coalition of 100 Black Women, and the Missionary Baptist Convention also voiced opposition to Bredesen ([

44], p. A9). The governor countered these claims by arguing that cutting TennCare would do more harm to rural and presumably white beneficiaries instead of urban or black residents [

45]. Notwithstanding this grassroots opposition, the governor and state legislature still moved forward with a major overhaul of TennCare in 2005.

The Appeals Process and Administrative Hearing Exams

At the height of the TennCare debate, the governor’s office and the TennCare Bureau made rule changes to the eligibility guidelines of TennCare beneficiaries. The proposal was then sent to the state legislative committees that monitored rule changes related to the adjudication of TennCare appeals. The new guidelines stacked the deck against TennCare beneficiaries.

The most controversial change to the appellate process was that it shifted hearing examinations from the Tennessee Department of State and its experienced law judges to the Department of Human Services, which had to hire new lawyers to review the TennCare appeals. This change raised larger concerns about the independence of the judicial process. A decade earlier, the American Bar Association outlined a series of recommendations that encouraged states to give independent panels of judges or “central hearing” panels power over administrative law hearings [

46]. From the standpoint of procedural justice, the central hearing panels produce fairer outcomes for appellants [

47]. Yet placing the TennCare appeals into the hands of inexperienced and temporary judges, who then had to adjudicate the appeals in the middle of a polarized political environment, undermined the confidence that health care advocates and some lawmakers had in the appellate process.

Another significant rule change targeted what would constitute a legitimate appeal by a TennCare beneficiary. The new rule promulgated that successful appeals could only address “valid factual” disputes. These disputes involved disabled beneficiaries and those who were disenrolled due to an administrative error such as a mistaken address [

48,

49]. In other words, the “valid factual disputes” provision narrowed the scope of viable TennCare appeals. Only one group—those with “a health, mental health, learning problem, or disability”—had a chance for an appeal outside of an administrative error.

The initial reports of the administrative hearing exams were disconcerting to advocates and lawmakers. Appellants had little, if any, room to explain their medical conditions outside of the merits of the factual disputes. The appeals application excluded certain medical conditions such as cancer (many conditions were identified as an “Open Category”) that might lead to disabilities or other conditions. Once the new rules were implemented, hearing examiners were instructed to give exclusive attention to appeals that only met the narrow criteria of valid factual disputes. According to Brian McGuire [

50], the chief lobbyist of Tennessee’s American Association of Retired Persons, appellants were “usually limited to what they put on forms and evidence of actual eligibility is ignored.” Yet they were not allowed to communicate this medical condition in the administrative hearing—a condition that would have made them eligible for re-enrollment—since it was not identified in the appeals application.

Though the valid factual dispute issue may seem insignificant, it is central to the debate about administrative hearings. Even when appellants believe they will lose an appeal decision, some will still seek procedural due process as long as the proceedings are fair ([

51]; [

52], pp. 819–20). Hearings that are preempted with procedural disadvantages undermine the confidence that appellants have in the administrative legal process.

Within six months of the rule changes, state lawmakers revisited the appellate process as part of their ex post powers ([

27], p. 310). This occurred after several media reports uncovered cases of beneficiaries who were unfairly treated in the appeal hearings. Representative Beverly Marrero of Memphis told DHS officials, “We’re hearing stories about people being overrun by the system” ([

2], p. B1). Other lawmakers expressed concern that only a fraction of former enrollees (350 out of 70,000) won their appeal hearings.

4. Data and Methods

This section uses logistic regressions to assess the procedural outcomes of the appellate process. The data for TennCare appeals were obtained through Tennessee Open Records requests with the Tennessee Department of Human Services. The request specifically asked for the racial and socio-demographic data of TennCare beneficiaries disenrolled from the program, as well as former beneficiaries who appealed their disenrollment. The dataset consists of a treasure trove of information with more than 60,000 individuals including approximately 8000 black TennCare beneficiaries who appealed their disenrollment from the program. Matching zip codes and county residences of the beneficiaries were included for each resident.

Dependent/Outcome Variables. The first dependent variable consists of a measurement called “Timely” that assesses if the beneficiary had a timely hearing. This dummy variable (1 = yes, 0 = no) examines whether the appeals process complied with the time frame established in the new guidelines and approved by the state’s Government and Operations Committee. Another dependent variable, “Fair Hearing” (1 = Fair Hearing, 0 = Not a Fair Hearing), is included in the model. The Department of State classified both variables for the purpose of the Open Records Request.

In addition to the racial background of the recipients, a racially polarized voting variable was created using ecological inference analyses that measured the black-white voting gap in each county. The TennCare Saves Live Coalition (TCSLC) collected data for each county based on the percentage of residents on TennCare and the total number of people who expected to be cut. The latter variable (TennCare cuts) was excluded in the models due to multicollinearity problems. However, other variables are included that account for the number of people expected to be cut by category: seniors or young people needing specialized health services; uninsured working-poor; uninsurable consumers or consumers with chronic health conditions; and senior citizens in need of supplemental prescription drug coverage. The data were collated from initial reports by the state’s Bureau of TennCare. These continuous variables are added to the model.

Another variable accounts for urban-rural divisions (1 = rural county, 0 = urban county) since Governor Bredesen claimed that TennCare would more adversely affect rural communities than cities. Bredesen’s attempt to recast the program as rural versus urban was designed to minimize black opposition to his reform package [

45]. One might expect rural respondents to have fairer and more timely hearings given his focus on this population compared to urban residents. A dummy variable was also created that measured whether a beneficiary lived in a county that was competitive in the 2002 gubernatorial elections.

Finally, a variable was created to identify beneficiaries living in counties that were targeted by advocacy groups such as the TCSLC. These “priority” counties were represented by lawmakers whose advocates believed were undecided in their support for the TennCare reforms. The variable was recoded accordingly: 0 = counties with no legislator on the TCSL target list, 1 = one legislator on the target list, 2 = more than one legislator in either the state House and/or Senate on the target list.

5. Findings

Before examining the logistic regressions, it is important to look more closely at the socio-demographic background of the TennCare beneficiaries seeking to have their disenrollment overturned.

Table 1 offers a portrait of the appellants during this critical period (2005–2006). Rural residents made up 43% of the appellants and the racial distribution (14% blacks and 85% whites) reflected the overall distribution of the state’s black and white population. More than 90% of the appellants had timely decisions, yet only 13% were reported as fair decisions.

Moreover, the data revealed that appellants lived in counties where the overall average TennCare population approached 25%. The group most affected by the cuts were working-poor residents who were uninsurable, with the second largest category being comprised of medically needy seniors and young people with acute health conditions (e.g., pregnancy) and disabilities. Many of these individuals were added to the program after TennCare/Medicaid was expanded in the mid-1990s.

The mean comparisons examining race and jurisdiction provide further insight into the differential outcomes of the appellate process.

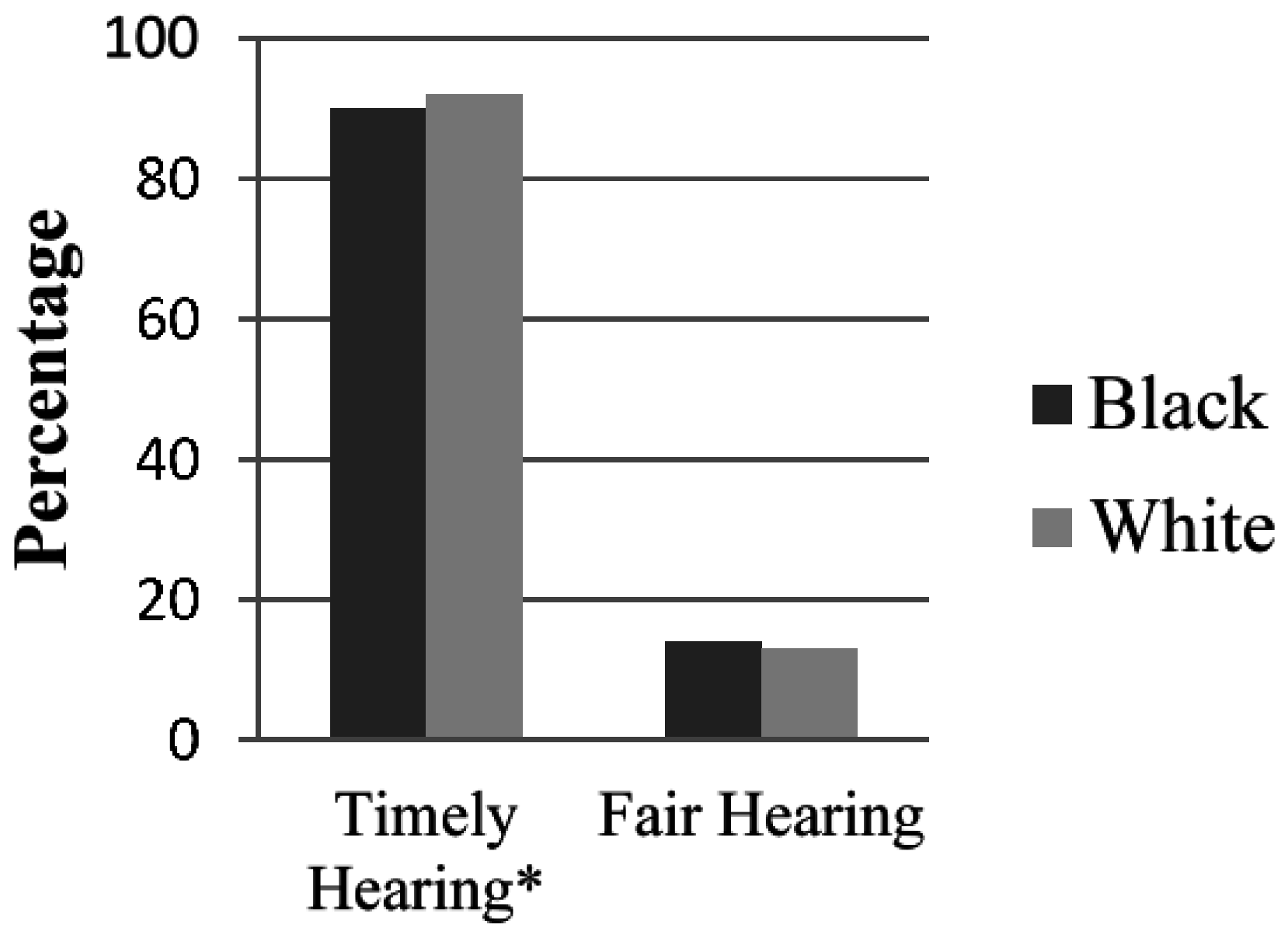

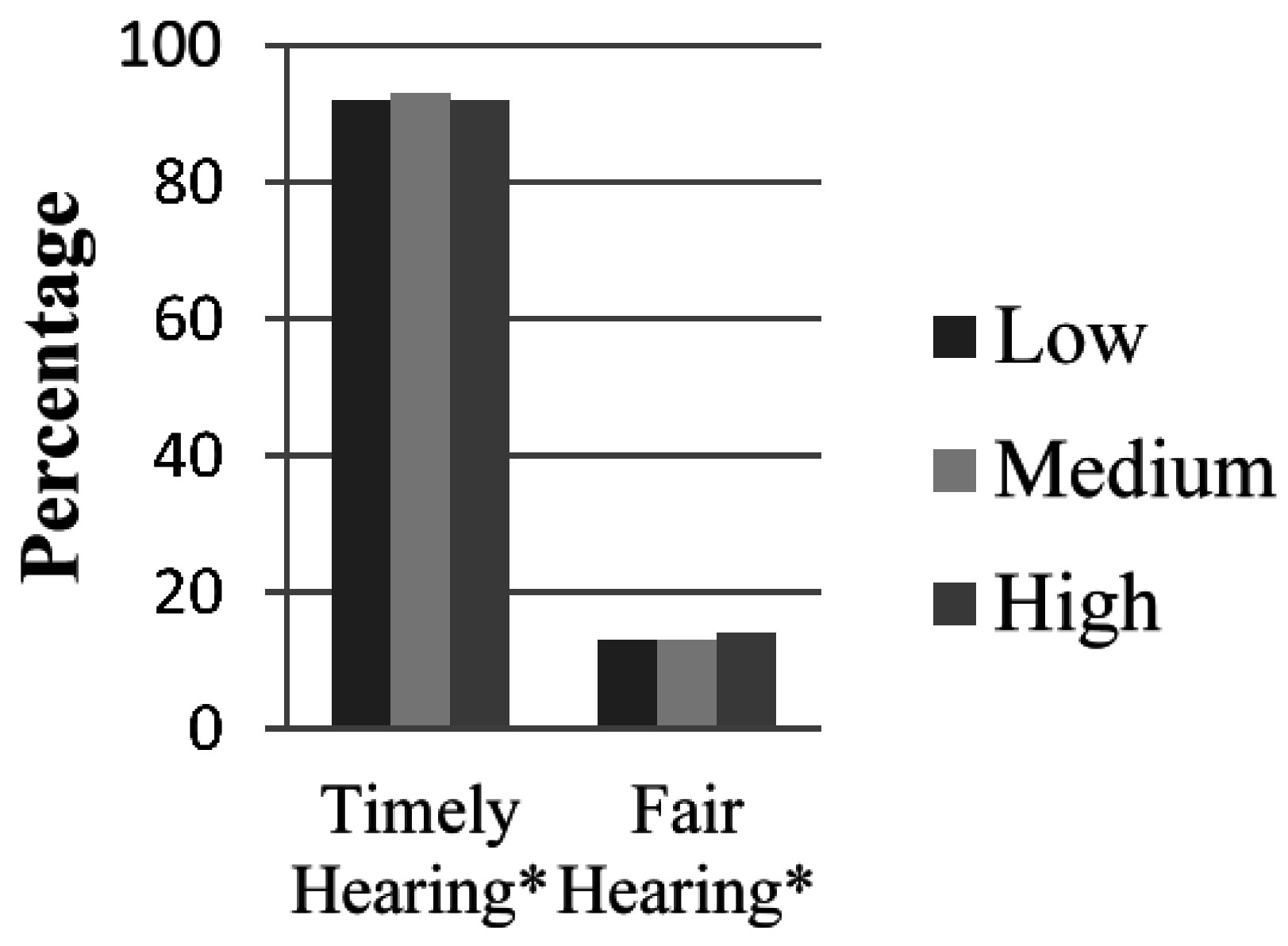

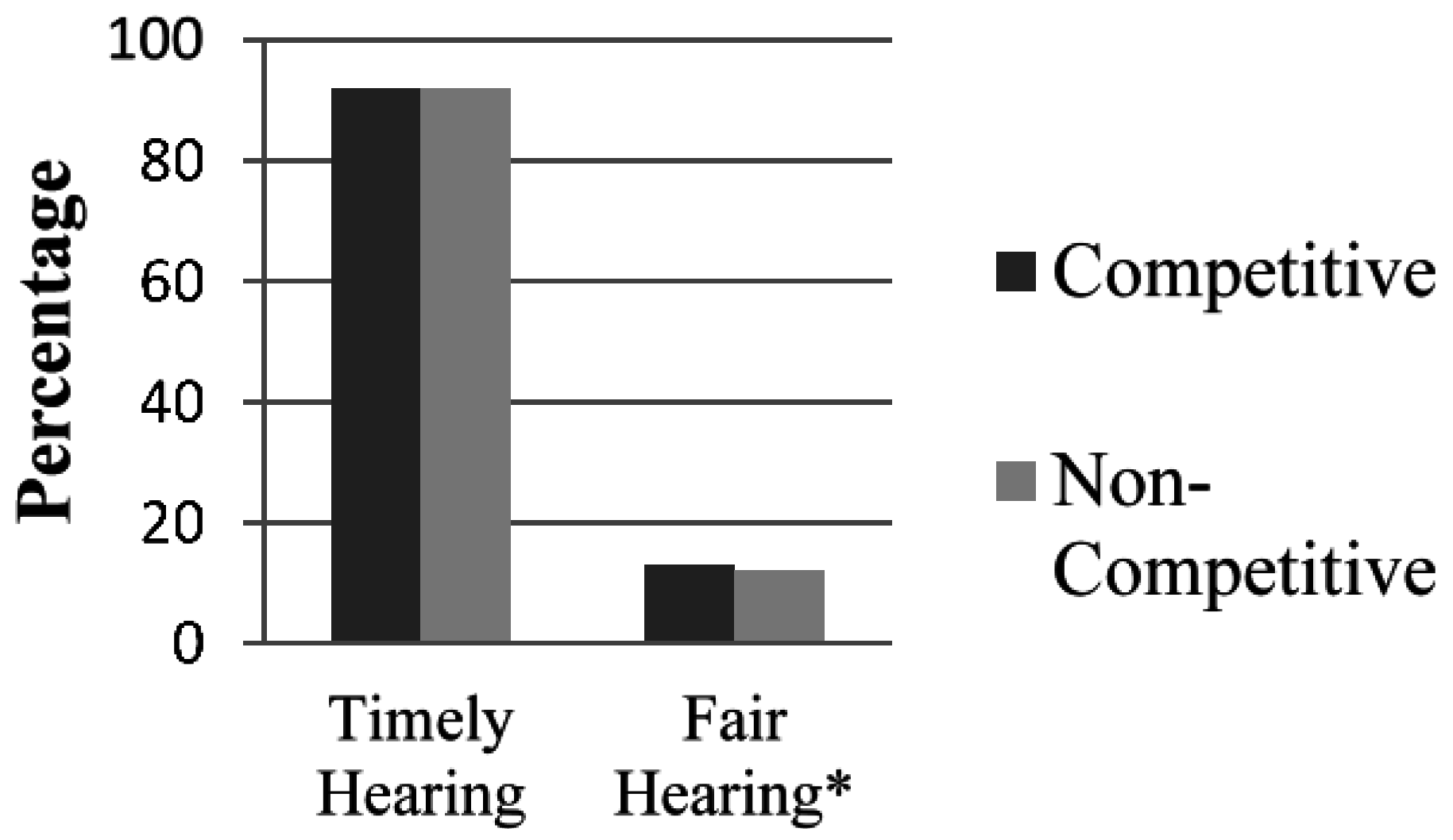

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 identify statistically significant (*

p < 0.05) findings for two assessments: whether the appeals process was resolved in timely fashion and if the process was fair to the appellants. Blacks were less likely to report a timely hearing for their appeals, although there were no statistically significant differences in the outcome of the hearings. Interestingly, rural residents were more likely to have their appeals reviewed in a timely fashion, but reported less favorable treatment in the outcome of the decisions. Appellants from counties that received moderate attention from health advocates were more likely to report timely hearings. Yet those from high-priority counties were more likely to receive favorable outcomes. Finally, there was no statistical significance in how quickly residents from competitive gubernatorial counties had appeal hearings. However, these residents were more likely to receive fair outcomes from the appeal hearings.

Next, the study provides a closer examination of the procedural outcomes of the administrative hearings. The findings do not look at the intent, but the outcome of the hearing exams. Our understanding is that the political environment can shape administrative law decisions even if there is no smoking gun that points to intent. The political environment is a coercive mechanism that shapes procedural outcomes [

6,

53]. For example, the ex ante procedures introduced to the Senate Government Operations Committee and the House Fiscal Review Committee stacked the deck such that many beneficiaries were faced with a procedural disadvantage in the appellate hearings.

Table 2 reports logistic regressions at a 95% confidence interval for timely and fair outcomes. The predicated correct percentage for both models was strong with 92.1% for timely hearings and 86.7% for fair hearings. The model fit, however, was much more significant for the model assessing fair hearings than timely hearings.

Overall, the mobilization strategy targeting priority counties had a positive impact on the time sequence of the appellate process, but the significance was minor (p < 0.10). Yet the appellant’s residence inside a priority county targeted by the advocacy coalition did not influence the outcome of the hearing examinations. The appellant’s residence inside a gubernatorial swing counties (counties where residents were divided in their choice for governor) also had no impact on both assessment measures.

Race had an interesting impact on appellate outcomes. Black appellants were less likely to receive timely hearings than whites, but race had no significance on determining if they received a fair outcome. Appellants from counties that had higher patterns of racially polarized voting were slightly (p < 0.10) more likely to receive timely hearings compared to other beneficiaries. However, they were also more likely to receive unfair outcomes compared to those who resided in counties where blacks and whites had similar voting patterns.

There were no differences in whether rural and urban residents received timely hearings. Although surprisingly, rural residents were more likely than urban constituents to claim that the appellate decisions were unfair. Beneficiaries from high-density TennCare counties were also no more likely to receive timely hearings than those living in counties with few TennCare beneficiaries. Yet, these beneficiaries reported significantly higher levels of unfair outcomes.

This study also examined whether timely and fair hearings were reported from beneficiaries living in counties with large TennCare populations earmarked as medically needy, uninsured working-poor, Medicaid eligible, and Medicare eligible. Only one of these subgroups produced statistically significant results. Beneficiaries living in counties where Medicare recipients needed TennCare to supplement prescription drug costs claimed that they received timely hearings. However, they insisted that the outcomes of these hearings were unfair. Coefficient measures for this variable were the strongest in both models.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

A central theme of this study is that the appellate process leads to differential outcomes that underscore racial and other ascriptive hierarchies. This claim is examined through the political battle over TennCare, Tennessee’s state Medicaid program that was drastically cut in 2005–2006 by Governor Bredesen. Although Medicaid was initially crafted as an insurance program for the nation’s poor [

54], in the 1990s, the program was extended in states such as Tennessee to working-poor beneficiaries and middle-income residents with severe chronic illnesses. Under TennCare, Medicaid was expanded to encompass disabled beneficiaries and the elderly who needed supplemental prescription drug coverage that was not paid for by Medicare or private insurance.

An instrumental component of Bredesen’s reform package was altering the appellate process for beneficiaries who were disenrolled from the program. Overall, the appellate process was produced a procedural disadvantage for some appellants. Hearing examiners were privy to the appellants’ socio-demographic information and medical conditions in the initial stage of the appeals process. More challenging was that the political context—the polarizing fight over Medicaid downsizing, the pressures of social movement groups, the governor’s bashing for TennCare—lead to a procedural backlash that reflected two outcomes. First, while most beneficiaries reported that their appeals were heard in a timely fashion, an overwhelming majority indicated that finality decisions were unfair. Secondly, the procedural backlash embedded biases in the final decisions of the appellate hearings that adversely affected some beneficiaries.

We hypothesized that hidden biases, with a specific interest in racial biases, shaped the appellate hearings. We found some evidence of that this was the case. It took longer for blacks to have their appeals heard compared to whites. However, there was no major difference between the racial groups regarding the fairness of the hearings.

The racial indicator underscores the significance of how blacks and whites assess universal and expanded health insurance programs. The racial animus attached to universal health care expansion has been well-documented [

55,

56]. While support for universal health insurance is strong, white support tends to fluctuate and is heavily influenced by partisanship [

55]. Strategies that promote the elimination of class-based disparities in healthcare also receive stronger support than those that seek to reduce racial-group-based disparities [

57]. Other research has shown that Medicaid beneficiaries have greater access to physicians in rural, white areas than similarly situated black communities ([

58], pp. 255–60). In fact, there is a lower rate of specialized physicians who service Medicaid patients in hypersegregated black communities.

One of the interesting findings that pertains to race is the racially polarized voting variable. Beneficiaries living in counties where blacks and whites were sharply divided in their choice for president were more likely to receive a timely hearing than those living in counties with homogenous voting patterns. Due to pressures from civil rights and health care advocacy groups, Bredesen was intent on minimizing opposition among African Americans. He even sent a letter to local officials in the summer 2005 titled “The Truth about TennCare Changes,” which explained that the TennCare cuts would mostly impact working-class counties in East Tennessee instead of urban areas where many blacks resided [

45]. This tactic may have signaled to hearing exams to be much more attentive about expediting appeal hearings from beneficiaries living in counties characterized by black-white voting gaps. The appeal hearings also occurred amidst his reelection gubernatorial campaign, which may have created an acute sensitivity to expediting the hearings for some beneficiaries. Yet, it is also worth noting that beneficiaries from racially polarized counties were more likely to be on the receiving end of unfair decisions.

In addition, we hypothesized that rural beneficiaries would be treated better than those from urban areas. This was primarily due to and long-standing patterns by lawmakers to rearrange federal-state programs in favor of rural, white communities in Tennessee. Yet contrary to our belief, rural appellants were actually treated unfavorably in the hearings, especially in the finality decisions. This was surprising given that rural communities were among the prime beneficiaries of Medicaid ([

58], pp. 255–60), and would seemingly have more urgency to leverage the appellate process.

In addition, black grassroots organizations and health care advocacy groups had developed a safety-net infrastructure for health care in urban areas. This infrastructure assisted beneficiaries in filling out the appeal applications for disenrolled beneficiaries [

41]. Representative Kathryn Bowers [

59], a leading black lawmaker from Memphis, the largest urban area in the state, was a vocal critic of the plan in her role as the Vice-Chair of the TennCare Oversight Committee in the state legislature. These collective efforts may have given beneficiaries from urban areas an advantage over rural areas in the appellate hearings.

Finally, we found little evidence that political signaling had a demonstrative impact the administrative procedures, thus disproving the third hypothesis. At best, beneficiaries that lived in districts targeted by health care advocates were slightly more likely to receive timely hearings than other recipients. Though minor in influence, civil rights and grassroots organizations expended a tremendous amount of energy educating their constituents in target counties about the adverse impact of the TennCare reforms.

Overall, the study underscores the need to take a second look at the administrative legal process. It is important to unlock this black box because it protects due process and can expand civil liberty protections for historically disadvantage groups. This will allow researchers to determine how racial biases, as well as other biases, are indicative of a complex policy backlash that is revealed in Medicaid appellate proceedings.