Sexual Motivations and Ideals Distinguish Sexual Identities within the Self-Concept: A Multidimensional Scaling Analysis

Abstract

:1. Sexual Motivations and Ideals Distinguish Sexual Identities within the Self-Concept: A Multidimensional Scaling Analysis

1.1. Psychological Differentiation of Sexual and Non-sexual Relationships

1.2. The Current Study

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Materials

2.3. Sexual Experience Variables

2.4. Sexual Motivation and Idealization Variables

2.5. Multidimensional Scaling Analysis

3. Results

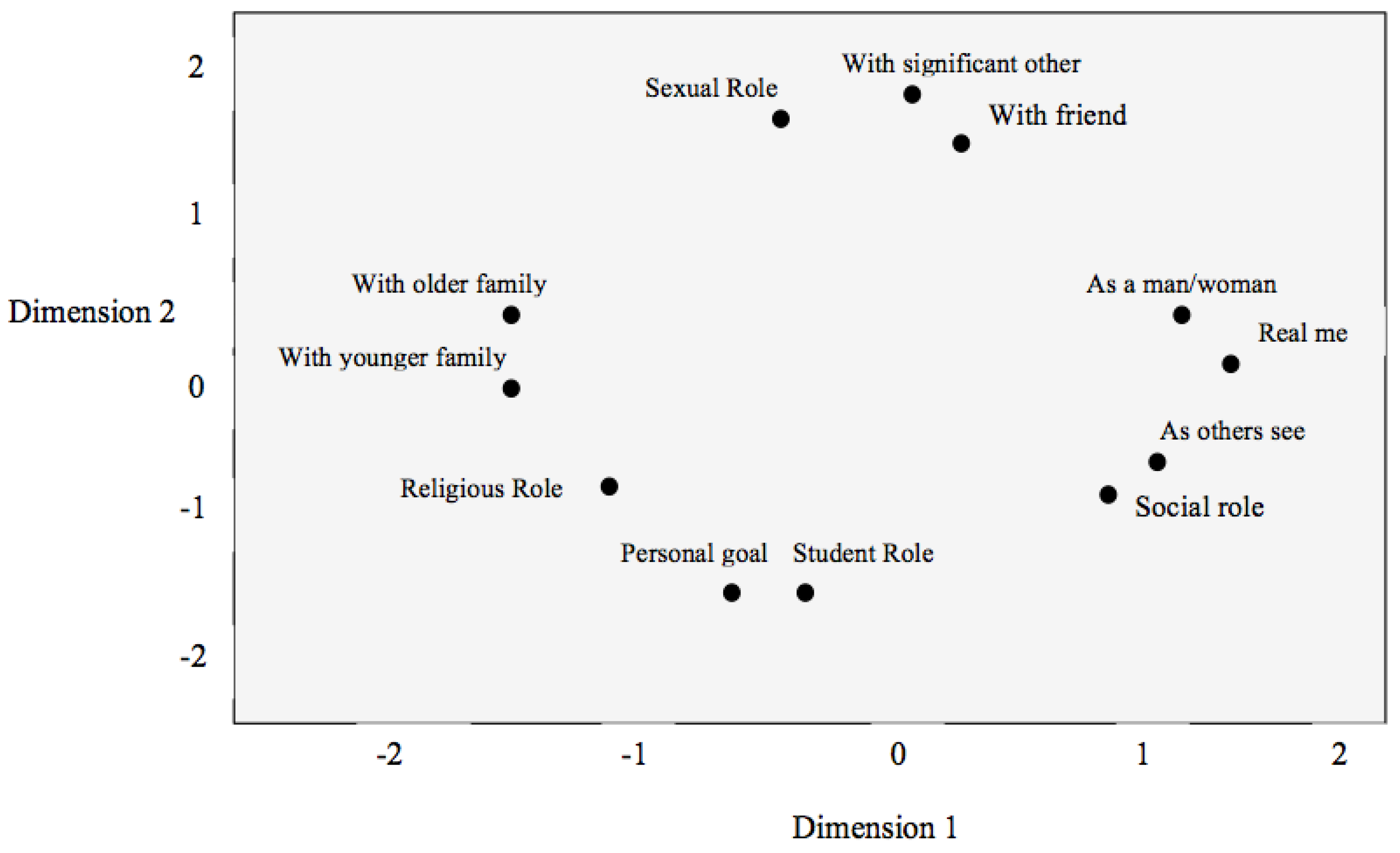

3.1. MDS Semantic Space Map

3.2. Correlations among Sexual Motivations, Idealization, and Identity Distinction

| Passion Idealization | Relational Idealization | |

|---|---|---|

| Dimension 1 weight | 0.25 * | −0.12 |

| Dimension 2 weight | 0.21 * | −0.03 |

| Passion Idealization | Relational Idealization | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Dimension 1 weight | 0.30 ** | −0.12 |

| Dimension 2 weight | 0.25 * | −0.02 | |

| Male | Dimension 1 weight | 0.18 | −0.23 |

| Dimension 2 weight | 0.15 | −0.08 |

| Intimacy | Enhance-ment | Self-Affirmation | Coping | Peer Pressure | Partner Approval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension 1 weight | 0.07 | 0.16 + | −0.07 | −0.02 | −0.10 | −0.06 |

| Dimension 2 weight | 0.11 | 0.14 | −0.06 | 0.01 | −0.12 | 0.08 |

| Intimacy | Enhancement | Self-Affirmation | Coping | Peer Pressure | Partner Approval | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Dimension 1 weight | 0.24 * | 0.24 * | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.14 | −0.14 |

| Dimension 2 weight | 0.23 * | 0.20 + | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.05 | |

| Male | Dimension 1 weight | −0.25 + | 0.07 | −0.22 | −0.21 | −0.23 | −0.27 |

| Dimension 2 weight | −0.13 | 0.05 | −0.18 | −0.24 | −0.24 | 0.22 + |

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Distinction of the Sexual Identity within the Self-Structure

4.2. Psychosocial Correlates of a Distinct Identities

Author Contributions

| Aggressive | Excited | Motivated | Romantic |

| Angry | Experienced | Not physically attractive | Sad |

| Arousable | Feeling | Open minded | Selfish |

| Assertive | Flashy | Optimistic | Sexual |

| Broad-minded | Friendly | Outgoing | Shame |

| Caring | Guilty | Outspoken | Shy |

| Confident | Happy | Passionate | Straightforward |

| Conservative | Honest | Physically attractive | Tired |

| Dependable | Inexperienced | Physically fit | Trusting |

| Direct | Insecure | Promiscuous | Vulnerable |

| Distant | Intelligent | Protective | Worried |

| Don’t care | Lazy | Respect | |

| Embarrassed | Loving | Revealing | |

Conflicts of Interest

References

- M. Lynne Cooper, Cheryl M. Shapiro, and Anne M. Powers. “Motivations for sex and risky sexual behavior among adolescents and young adults: A functional perspective.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 75 no. 6. (1998): 1528–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laura H. Dawson, Mei-Chiung Shih, Carl de Moor, and Lydia Shrier. “Reasons why adolescents and young adults have sex: Associations with psychological characteristics and sexual behavior.” Journal of Sex Research 45 no. 3. (2008): 225–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raymond C. Rosen, and Gloria A. Bachmann. “Sexual well-being, happiness, and satisfaction, in women: The case for a new conceptual paradigm.” Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy 34 no. 4. (2008): 291–97. [Google Scholar]

- Erik Homburger Erikson. Identity and the Life Cycle. New York: WW Norton & Company, 1980, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Erik Homburger Erikson. “The problem of ego identity.” Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association 4 (1956): 56–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- James William. The Principles of Psychology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1890. [Google Scholar]

- Robert L. Woolfolk, James Novalany, Michael A. Gara, Lesley A. Allen, and Monica Polino. “Self-complexity, self-evaluation, and depression: An examination of form and content within the self-schema.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 68 no. 6. (1995): 1108–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaela Hynie, John E. Lydon, Sylvana Cote, and Seth Wiener. “Relational sexual scripts and women’s condom use: The importance of internalized norms.” Journal of Sex Research 35 no. 4. (1998): 370–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- William Simon, and John H. Gagnon. “Sexual scripts: Permanence and change.” Archives of sexual Behavior 15 no. 2. (1986): 97–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seymour Rosenberg. “Multiplicity of selves.” In Self and Identity: Fundamental Issues. Edited by Richard D. Ashmore and Lee Jussim. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997, vol. 1, pp. 23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel M. Ogilvie, and Richard D. Ashmore. “Self-with-other representation as a unit of analysis in self-concept research.” In The Relational Self: Theoretical Convergences in Psychoanalysis and Social Psychology. Edited by Rebecca C. Curtis. New York: Guilford Press, 1991, pp. 282–315. [Google Scholar]

- Steve M. Jenkins, Walter C. Buboltz Jr., Jonathan P. Schwartz, and Patrick Johnson. “Differentiation of self and psychosocial development.” Contemporary Family Therapy 27 no. 2. (2005): 251–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray Bowen. Family Therapy in Clinical Practice. Lanham: Jason Aronson, Inc., 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Elizabeth A. Skowron, and Thomas A. Schmitt. “Assessing interpersonal fusion: Reliability and validity of a new DSI fusion with others subscale.” Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 29 no. 2. (2003): 209–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kathleen M. White, Joseph C. Speisman, Doris Jackson, Scott Bartis, and Daryl Costos. “Intimacy maturity and its correlates in young married couples.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 50 no. 1. (1986): 152–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurit E. Birnbaum, Harry T. Reis, Mario Mikulincer, Omri Gillath, and Ayala Orpaz. “When sex is more than just sex: Attachment orientations, sexual experience, and relationship quality.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 91 no. 5. (2006): 929–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R. Chris Fraley, and Phillip R. Shaver. “Adult romantic attachment: Theoretical developments, emerging controversies, and unanswered questions.” Review of General Psychology 4 no. 2. (2000): 132–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaela Hynie, and John E. Lydon. “Sexual attitudes and contraceptive behavior revisited: Can there be too much of a good thing? ” Journal of Sex Research 33 no. 2. (1996): 127–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrea C. Vial, and Warren A. Reich. “A hierarchical analysis the sexual self of college men and women.” Unpublished work. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Caryl E. Rusbult, and Isabella M. Zembrodt. “Responses to dissatisfaction in romantic involvements: A multidimensional scaling analysis.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 19 no. 3. (1983): 274–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richard J. Viken, Teresa A. Treat, Robert M. Nosofsky, Richard M. McFall, and Thomas J. Palmeri. “Modeling individual differences in perceptual and attentional processes related to bulimic symptoms.” Journal of Abnormal Psychology 111 no. 4. (2002): 598–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandra L. Robinson, and Rebecca J. Bennett. “A typology of deviant workplace behaviors: A multidimensional scaling study.” Academy of Management Journal 38 no. 2. (1995): 555–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbara L. Andersen, and Jill M. Cyranowski. “Women’s sexual self-schema.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67 no. 6. (1994): 1079–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren A. Reich, Ellen M. Kessel, and Frank J. Bernieri. “Life Satisfaction and the Self: Structure, Content, and Function.” Journal of Happiness Studies 14 no. 1. (2013): 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. Douglas Carroll, and Phipps Arabie. “Multidimensional scaling.” In Measurement, Judgment, and Decision Making. Edited by Michael H. Birnbaum. San Diego: Academic Press, 1998, pp. 179–250. [Google Scholar]

- Cindy Hazan, and Debra Zeifman. “Sex and the psychological tether.” In Advances in personal relationships: Attachment Processes in Adulthood. Edited by Kim Bartholomew and Daniel Perlman. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 1994, vol. 5, pp. 151–78. [Google Scholar]

- Phillip R. Shaver, and Mario Mikulincer. “A behavioral systems approach to romantic love relationships: Attachment, caregiving, and sex.” In The New Psychology of Love. Edited by Robert J. Sternberg and Karin Weis. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006, pp. 35–64. [Google Scholar]

- John DeLamater. “Gender differences in sexual scenarios.” In Females, Males, and Sexuality: Theories and Research. Binghamton: Vail-Ballou Press, 1987, pp. 127–39. [Google Scholar]

- L. Monique Ward, and Kimberly Friedman. “Using TV as a guide: Associations between television viewing and adolescents’ sexual attitudes and behavior.” Journal of Research on Adolescence 16 no. 1. (2006): 133–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diana T. Sanchez, Corinne A. Moss-Racusin, Julie E. Phelan, and Jennifer Crocker. “Relationship contingency and sexual motivation in women: Implications for sexual satisfaction.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 40 no. 1. (2011): 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leslie Winfield Ballentine, and Jennifer Paff Ogle. “The making and unmaking of body problems in Seventeen magazine, 1992–2003.” Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal 33 no. 4. (2005): 281–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janell Lucille Carroll, Kari Doray Volk, and Janet Shibley Hyde. “Differences between males and females in motives for engaging in sexual intercourse.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 14 no. 2. (1985): 131–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbara Critchlow Leigh. “Reasons for having and avoiding sex: Gender, sexual orientation, and relationship to sexual behavior.” Journal of Sex Research 26 no. 2. (1989): 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnie J. Randolph, and Barbara Winstead. “Sexual decision making and object relations theory.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 17 no. 5. (1988): 389–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly A. Brennan, Shey Wu, and Jennifer Loev. “Adult romantic attachment and individual differences in attitudes toward physical contact in the context of adult romantic relationships.” In Attachment Theory and Close Relationships. Edited by Jeffry A. Simpson and W. Steven Rholes. New York: Guilford Press, 1998, pp. 394–428. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly A. Brennan, Catherine L. Clark, and Phillip R. Shaver. “Self-report measurement of adult attachment.” In Attachment Theory and Close Relationships. Edited by Jeffry A. Simpson and W. Steven Rholes. New York: Guilford Press, 1998, pp. 46–76. [Google Scholar]

- Elizabeth A. Skowron, and Myrna L. Friedlander. “The Differentiation of Self Inventory: Development and initial validation.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 45 no. 3. (1998): 235–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwen A. Hawley. MPD, Measures of Psychosocial Development: Professional Manual. Odessa: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc., 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Sally L. Archer, and Jeremy A. Grey. “The sexual domain of identity: Sexual statuses of identity in relation to psychosocial sexual health.” Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research 9 no. 1. (2009): 33–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1Other materials were given but are not reported here because they are not relevant to the current analyses.

© 2014 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sangiorgio, C.; Reich, W.A.; Vial, A.C.; Savone, M. Sexual Motivations and Ideals Distinguish Sexual Identities within the Self-Concept: A Multidimensional Scaling Analysis. Soc. Sci. 2014, 3, 215-226. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci3020215

Sangiorgio C, Reich WA, Vial AC, Savone M. Sexual Motivations and Ideals Distinguish Sexual Identities within the Self-Concept: A Multidimensional Scaling Analysis. Social Sciences. 2014; 3(2):215-226. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci3020215

Chicago/Turabian StyleSangiorgio, Celeste, Warren A. Reich, Andrea C. Vial, and Mirko Savone. 2014. "Sexual Motivations and Ideals Distinguish Sexual Identities within the Self-Concept: A Multidimensional Scaling Analysis" Social Sciences 3, no. 2: 215-226. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci3020215