Reflection, Ritual, and Memory in the Late Roman Painted Hypogea at Sardis

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Roman Sardis and the Painted Hypogea

3. Standard Decorative Program and Technique

4. Exceptional Tombs and Chronology

God (the boethei) give help to Fl[avios] Chrysanthios, doukenarios fabrikesios, (who) for himself and his family built this tomb with his wife and childrenFl[avios] Chrysanthios built this tombFl[avios] Chrysanthios doukenarios zographos fabrikesios built this tomb

5. The Broader Context: Painting Style and Comparanda

6. Funerary Ritual

7. Conclusions: Sardis’ Wall Painting in the Context of Late Antique Art

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Catalogue of Painted Hypogea at Sardis50

Appendix A.1. T1. The “Tomb of Chrysanthios” (Tomb 76.1), Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6 and Figure 751

Appendix A.2. T2. The “Painted Tomb,” Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 1155

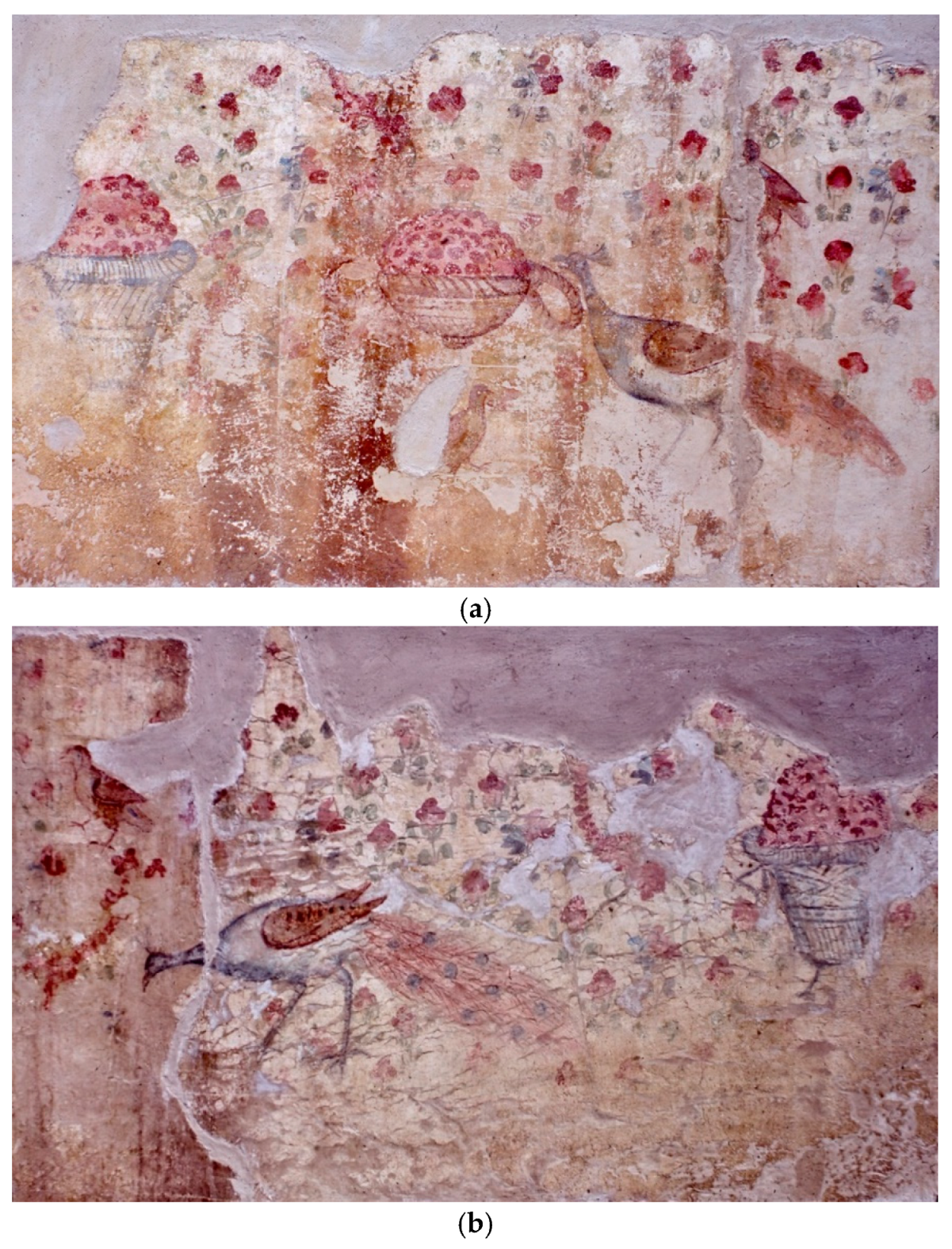

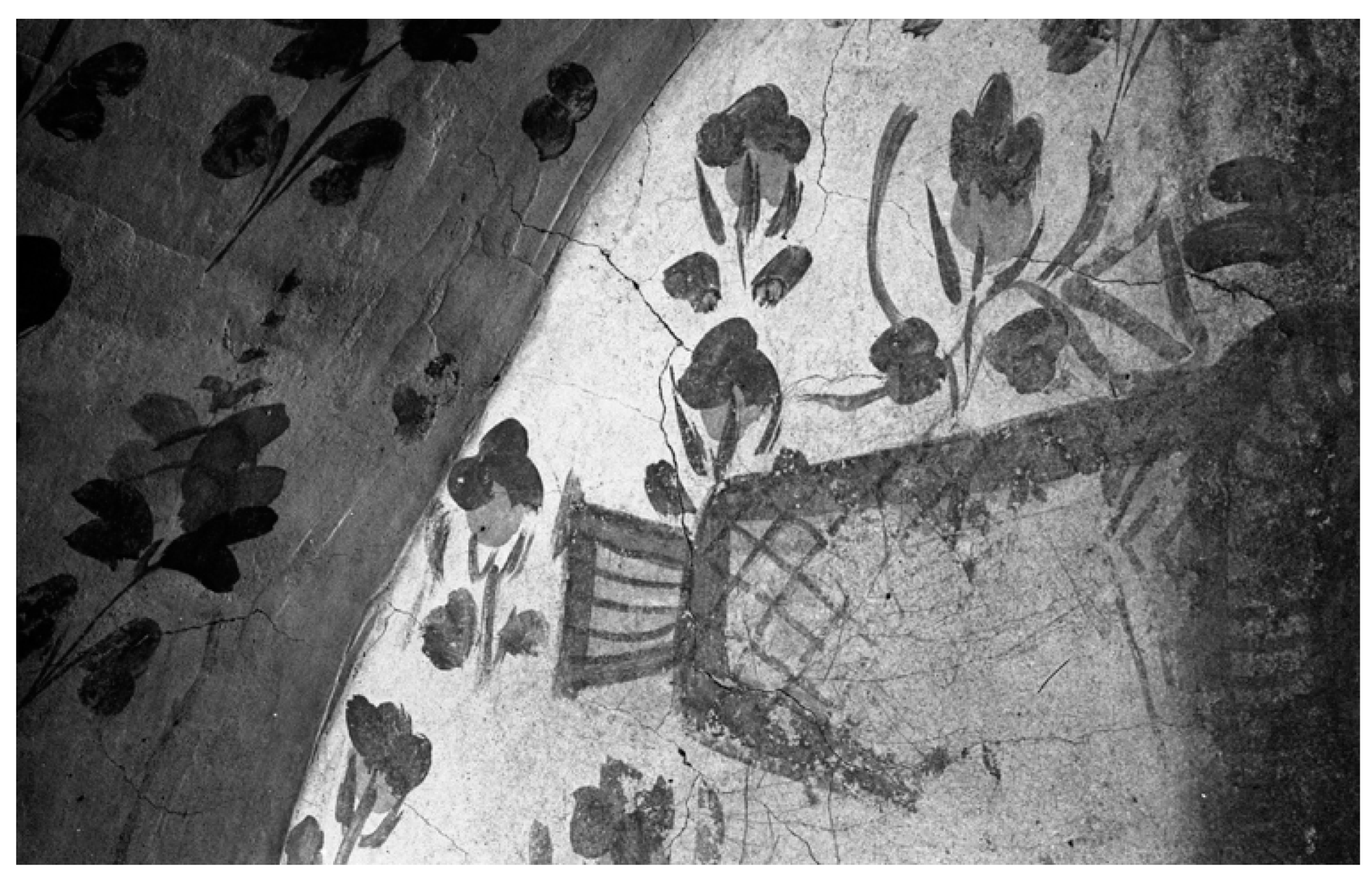

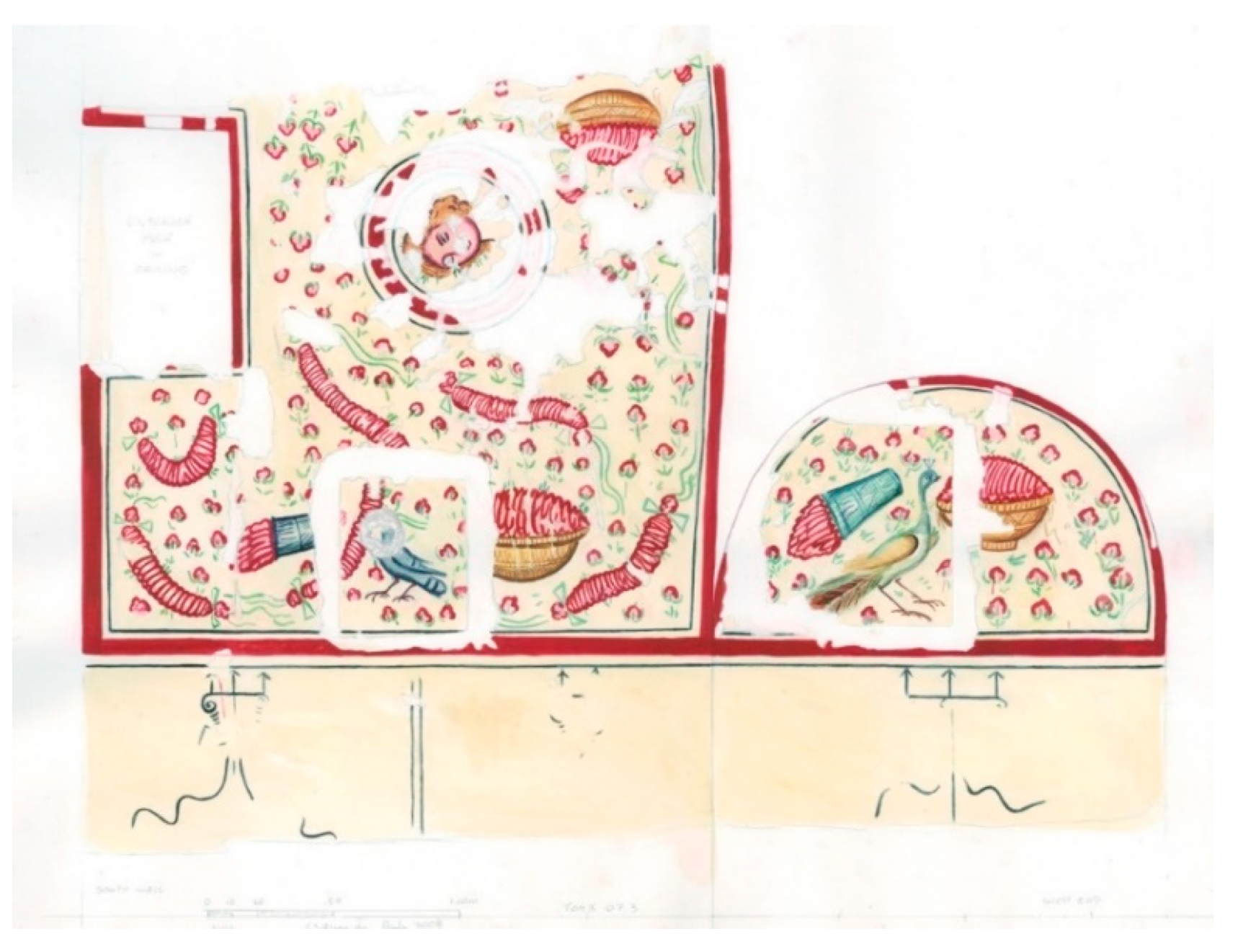

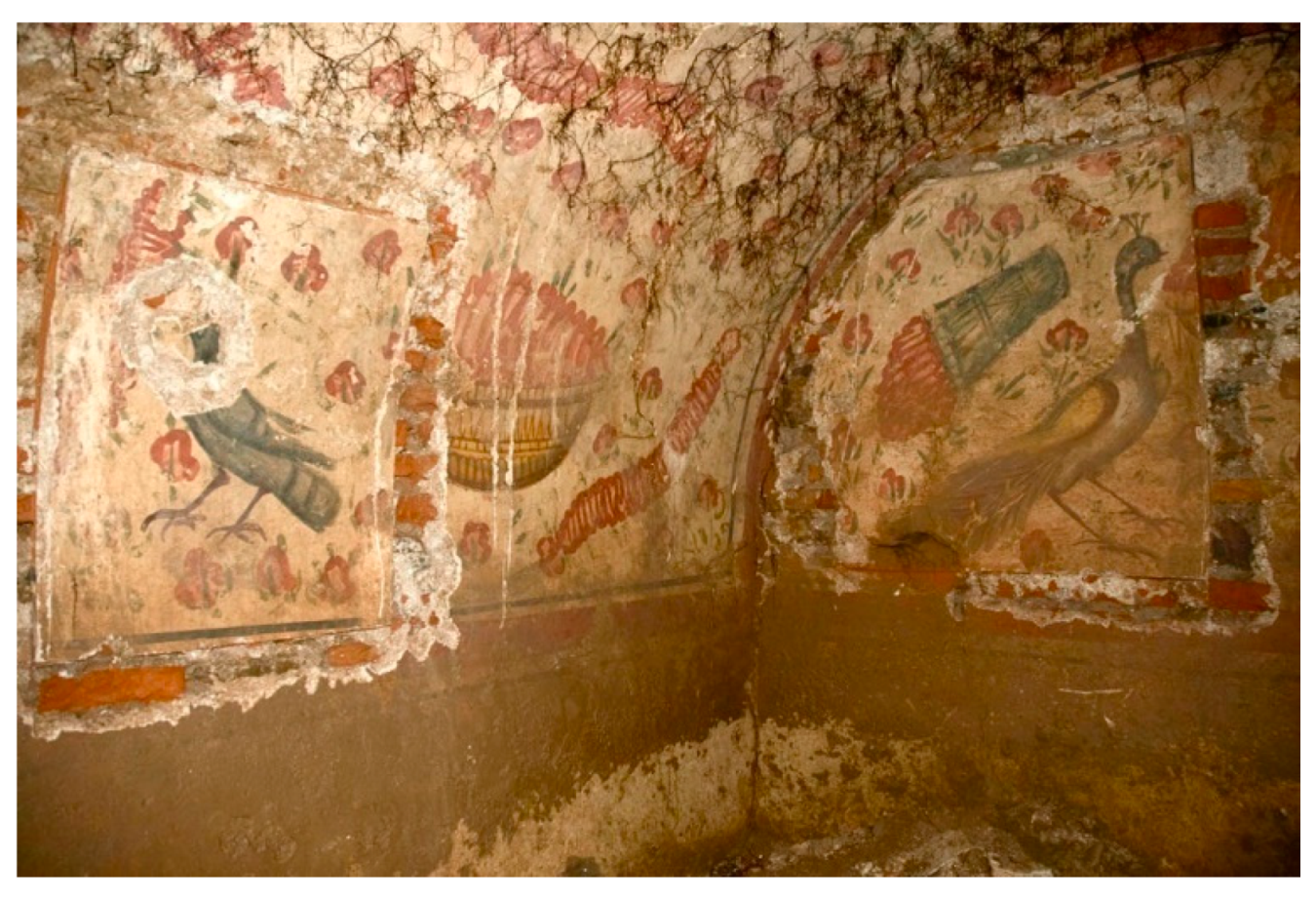

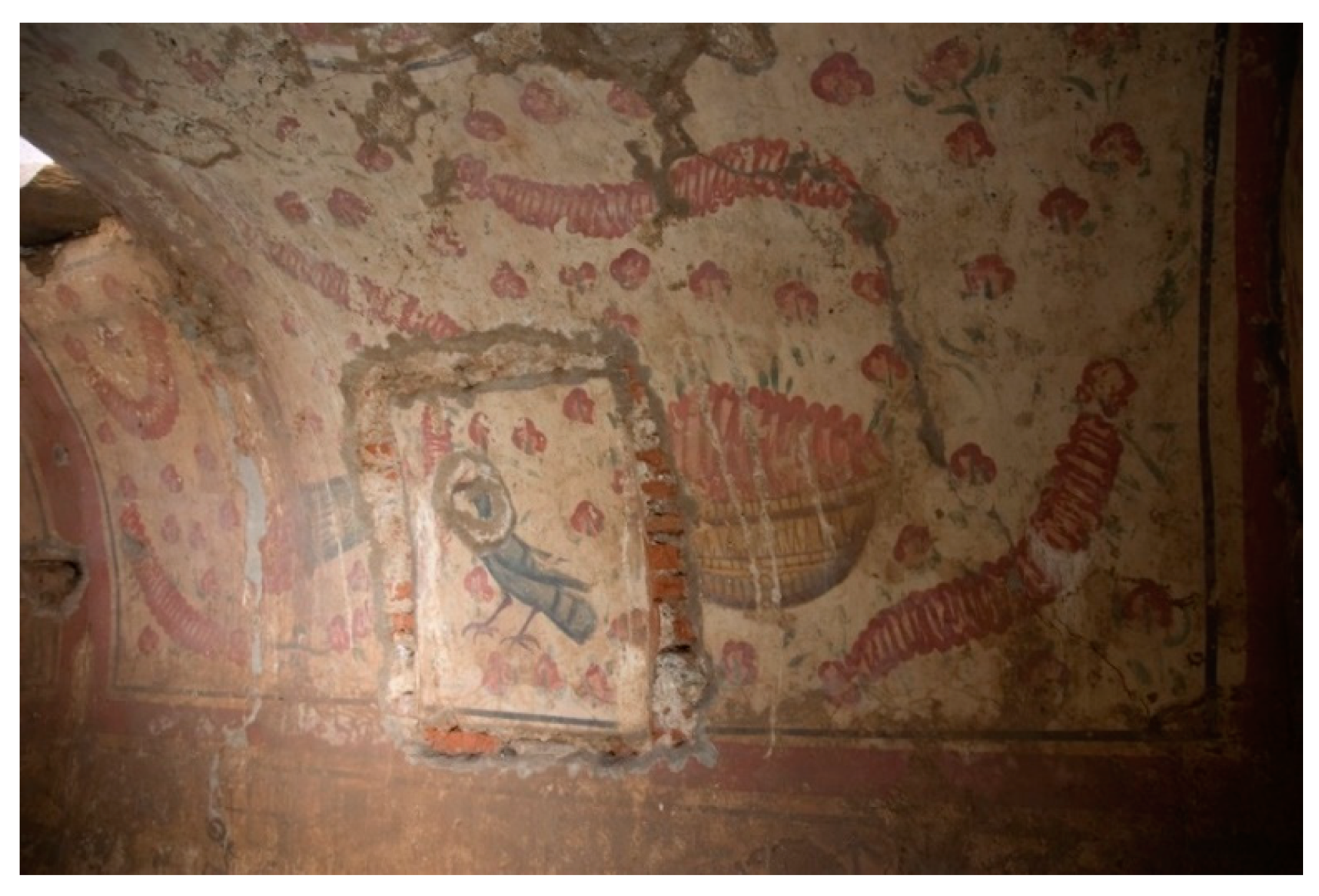

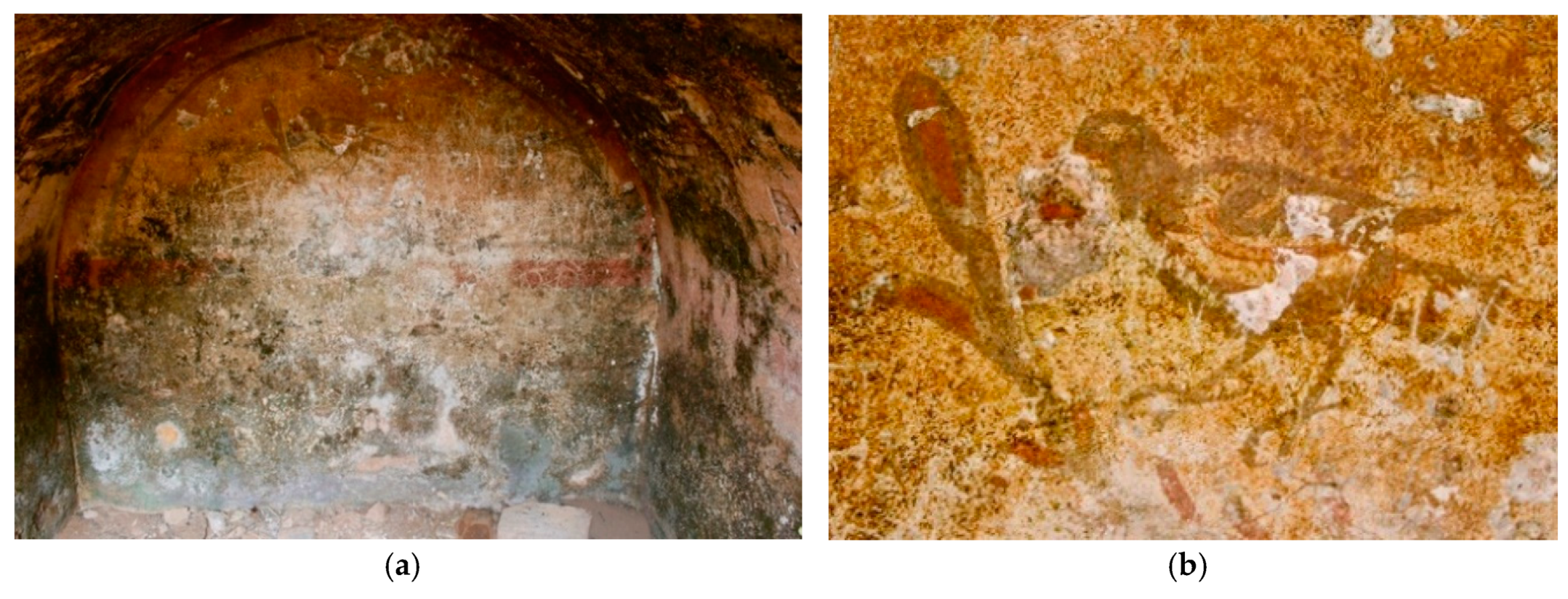

Appendix A.3. T3. The “Peacock Tomb” (Tomb 61.14), Figure A1 and Figure A258

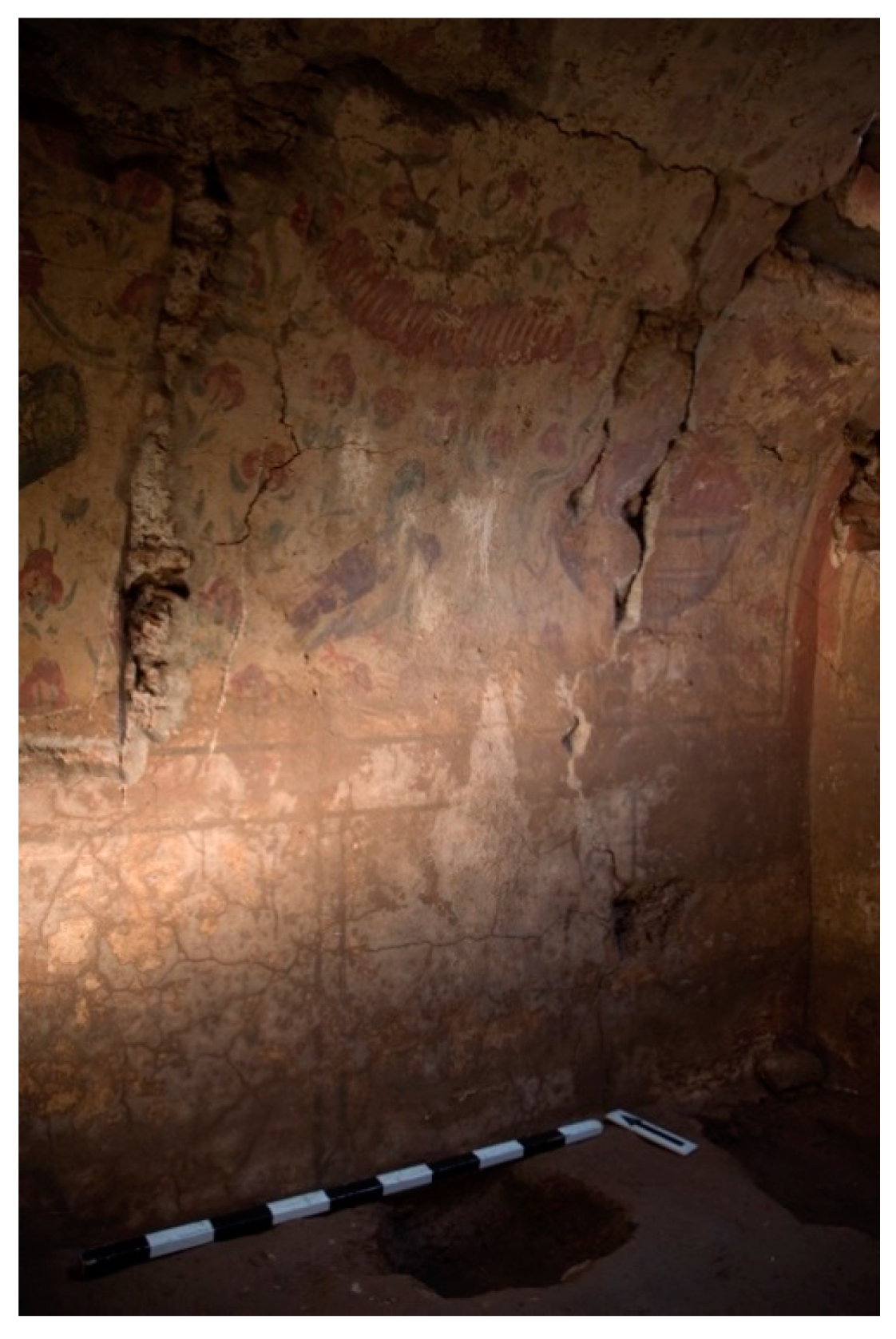

Appendix A.4. T4. Tomb 93.1, Figure A3, Figure A4 and Figure A561

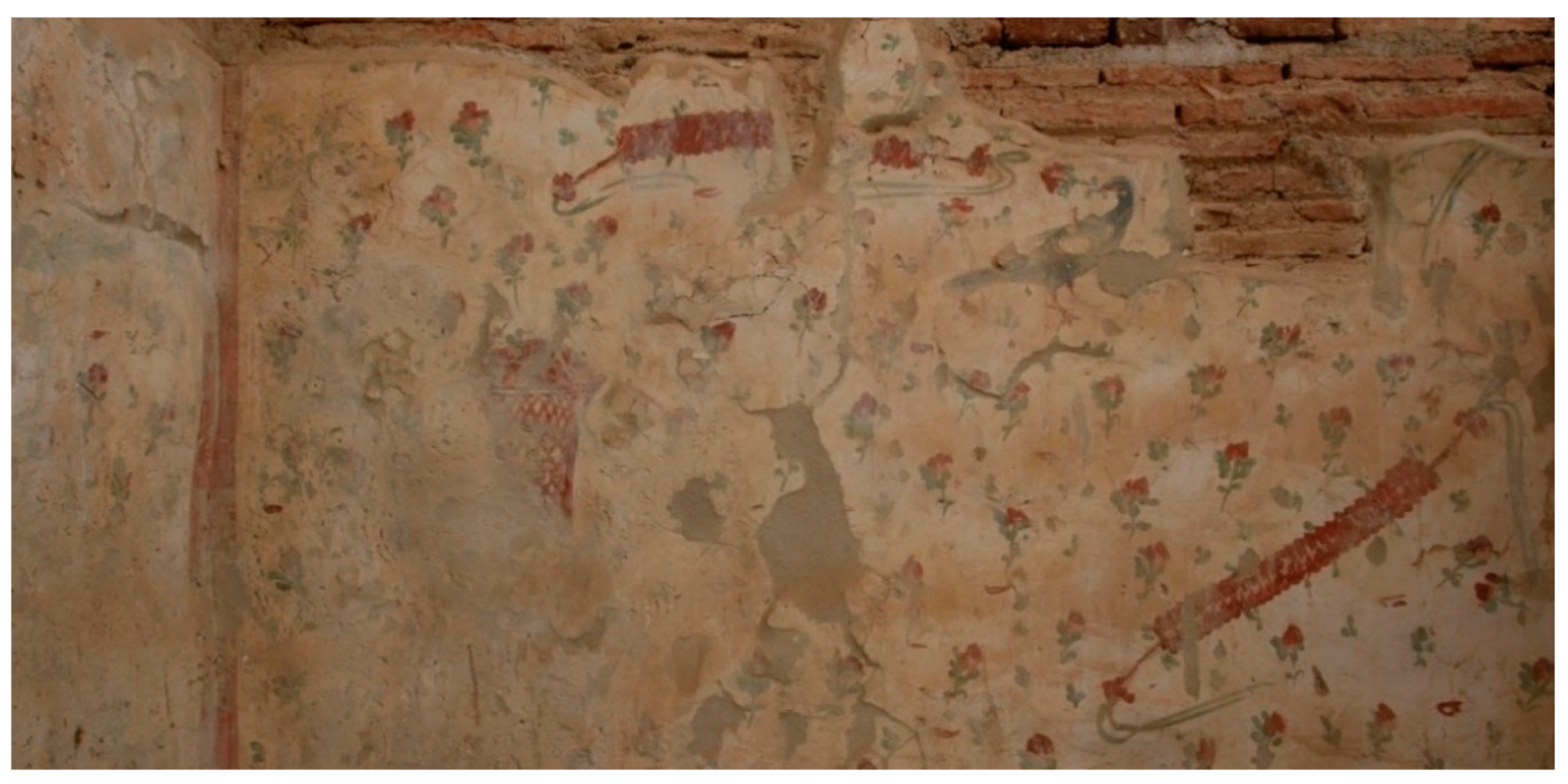

Appendix A.5. T5, T6. Tombs 07.2 (Figure A6, Figure A7 and Figure A8) and 07.3 (Figure 1, Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17)62

Appendix A.6. T7. 79.2, Figure A9, Figure A10 and Figure A1164

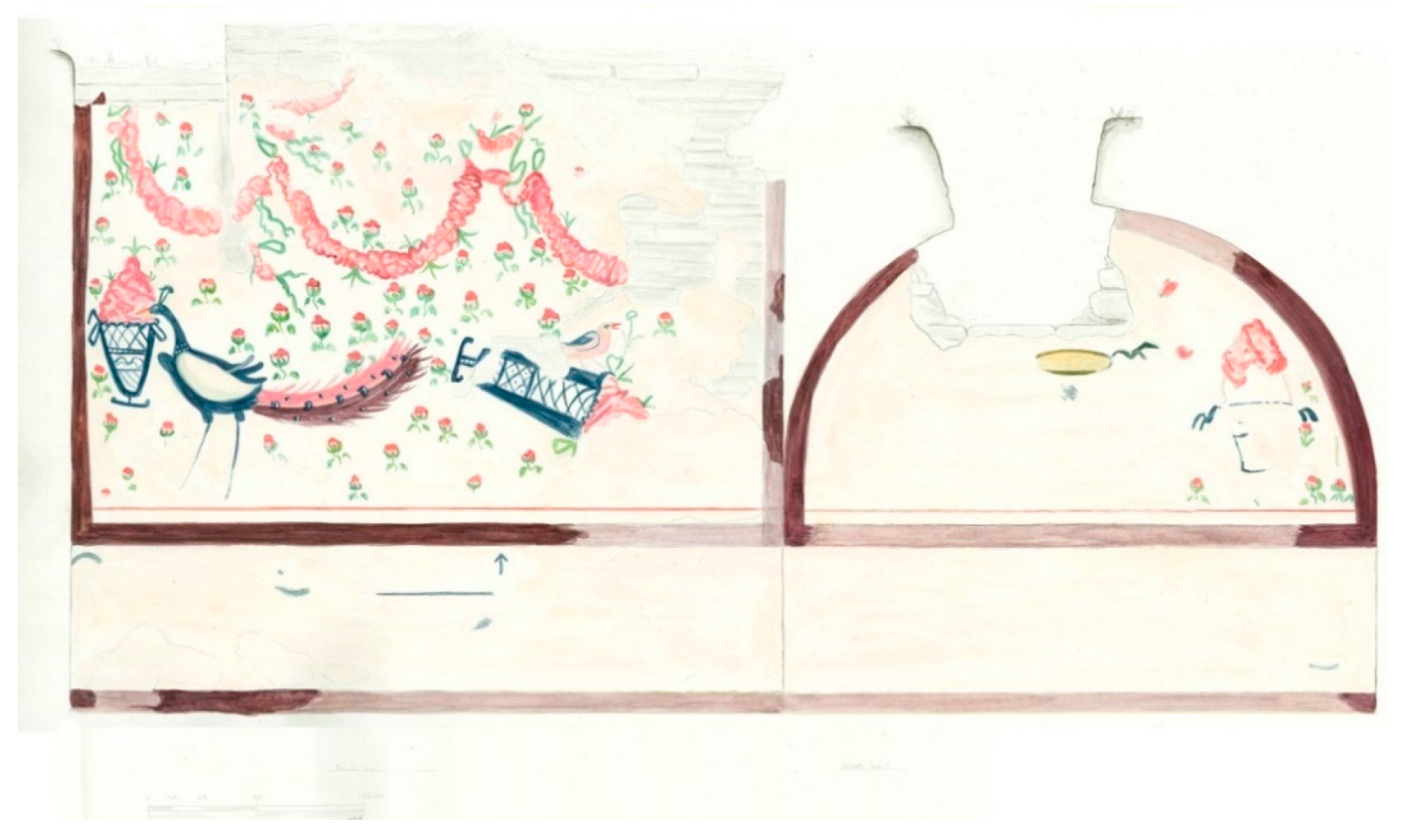

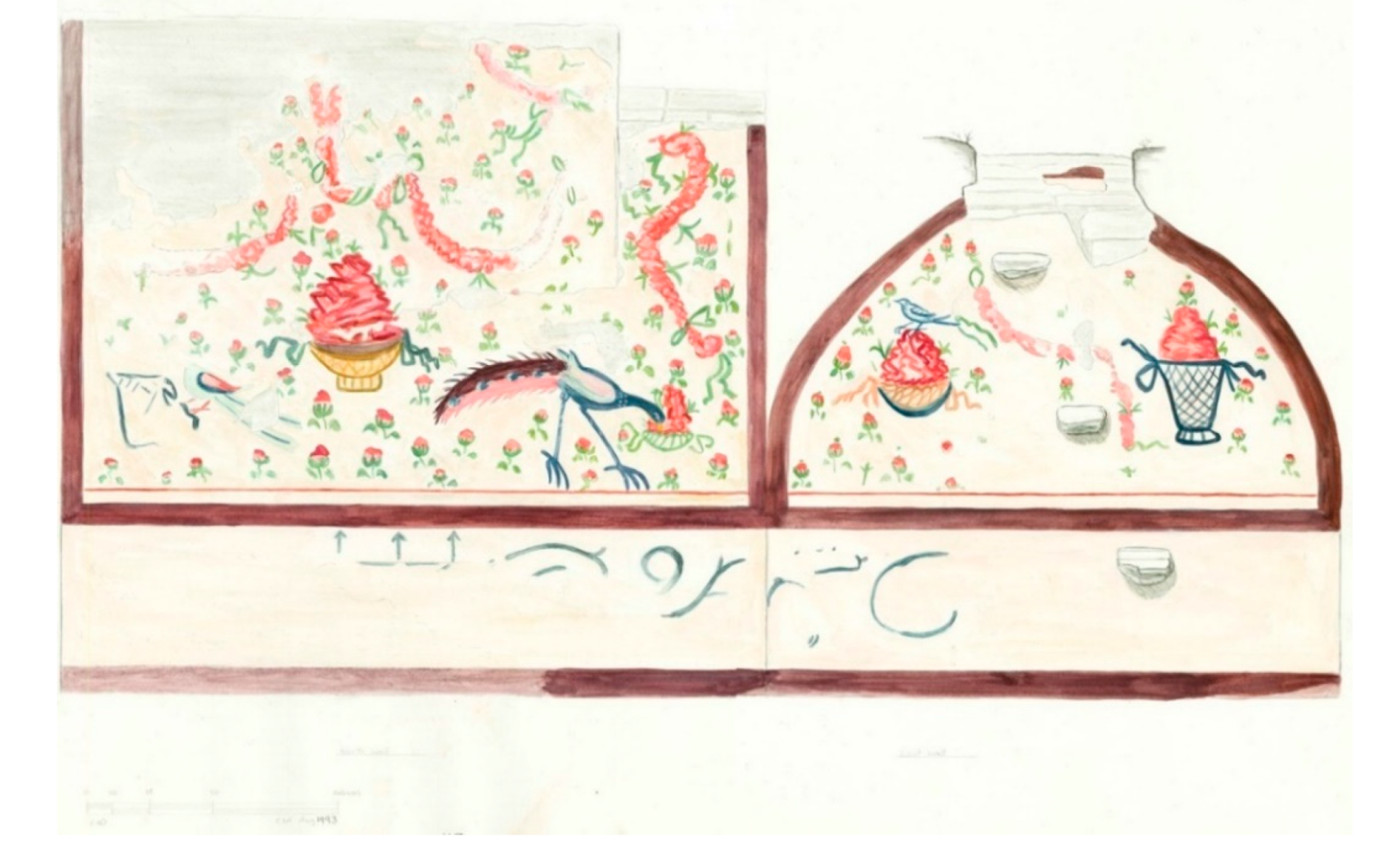

Appendix A.7. T8. Kâgirlik Tepe Tomb, Figure 18, Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21 and Figure 2268

Appendix A.8. T9. Tomb 79.1, Figure 23 and Figure 2472

Appendix A.9. T10. Artemis Precinct Tomb (Tomb AT.2), Figure 25 and Figure 2674

Appendix A.10. T11. Tomb under the House of the Bronzes (HoB), Unit 1678

Appendix A.11. T12. Pactolus Cliff (LVC and SVC)81

References

- Alexander, Catherine Swift. 2008. 2008 Drafting Report, Unpublished report. Archaeological Exploration of Sardis.

- Alföldi-Rosenbaum, Elisabeth. 1971. Anamur Nekropolü. The Necropolis of Anemurium. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi. [Google Scholar]

- Barbet, Alix. 2005. Zeugma II. Peintures Murales Romaines. Istanbul: Institut français D’études Anatoliennes-Georges Dumézil. [Google Scholar]

- Barbet, Alix. 2007. Le chrisme dans la peinture murale romaine. In Konstantin der Grosse: Geschichte, Archäologie, Rezeption; internationales Kolloquium vom 10–15 Oktober 2005 an der Universität Trier zur Landesausstellung Rheinland-Pfalz. Edited by Alexander Demandt and Josef Engemann. Trier: Rheinisches Landesmuseum, pp. 127–41. [Google Scholar]

- Barbet, Alix. 2014. Le Semis de Fleurs en Peinture Murale entre Mode et Style? In Actes du XIe Colloqie de l’Association Internationale pour la Peinture Murale Antique (Ephesos 13–17 September, 2010). Edited by Norbert Zimmermann. Vienna: Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, pp. 199–207. [Google Scholar]

- Barbet, Alix, and Claude Vibert-Guigue. 1994. Les Peintures des Nécropoles Romaines D’Abila Et Du Nord De La Jordanie. Beyrouth: Institut Français d’Archéologie du Proche-Orient. [Google Scholar]

- Barbet, Alix, Pierre-Louis Gatier, and Norman N. Lewis. 1997. Un tombeau peint inscrit de Sidon. Syria 74: 141–60. [Google Scholar]

- Bisconti, Fabrizio. 2002. The Decoration of the Roman Catacombs. In The Christian Catacombs of Rome. Edited by Vincenzo Fiocchi Nicolai, Fabrizio Bisconti and Danilo Mazzoleni. Translated by Cristina Carlo Stella, and Lori-Ann Touchette. Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner, pp. 71–145. [Google Scholar]

- Borg, Barbara. 2013. Crisis and Ambition: Tombs and Burial Customs in Third-Century CE Rome. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Buchwald, Hans. 2015. Churches EA and Eat Sardis. Archaeological Exploration of Sardis, Report 6. Cambridge: Archaeological Exploration of Sardis. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, Howard Crosby. 1913. Fourth Preliminary Report on the American Excavations at Sardes in Asia Minor. American Journal of Archaeology 17: 471–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, Howard Crosby. 1922. Sardis, The Excavations Part I, 1910–1914. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Calza, Guido. 1940. La necropoli del Porto di Roma nell’ Isola Sacra. Roma: La Libreria Dello Stato. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, Maureen. 2006. Spirits of the Dead: Roman Funerary Commemoration in Western Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, John R. 1991. The Houses of Roman Italy, 100 B.C.-A.D. 250: Ritual, Space, and Decoration. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, John R. 2003. Art in the Lives of Ordinary Romans: Visual Representation and Non-Elite Viewers in Italy, 100 B.C.-A.D. 315. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Connerton, Paul. 1989. How Societies Remember. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cormack, Sarah. 1997. Funerary Monuments and Mortuary Practice in Roman Asia Minor. In The Early Roman Empire in the East. Edited by Susan Alcock. Oxford: Oxbow Monograph 95, pp. 137–56. [Google Scholar]

- Cumont, Franz Valery Marie. 1942. Recherches sur le Symbolisme Funéraire des Romains. Paris: P. Geuthner. [Google Scholar]

- D’Angelo, Tiziana. 2008. Tomb 07.2 and Tomb 07.3 Mid-Season Report. Unpublished report, Archaeological Exploration of Sardis. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Douglas James. 2002. Death, Ritual and Belief: The Rhetoric of Funerary Rites. New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Del Chiaro, Maria A. 1960. Pactolus Cliff Excavations, 1960. Unpublished Report, Archaeological Exploration of Sardis. [Google Scholar]

- Deleman, İnci. 2008. Perge’den bir Yemek Sahnesinde Batı Yankıları. In Festschrift für Prof. Dr. Haluk Abbasoğlu zum 65. Haluk Abbasoğlu zum 65 Geburtstag. Edited by İnci Deleman, Sedef Çokay-Kepçe, Aşkım Özdizbay and Özgür Turak. İstanbul: AKMED, vol. 1, pp. 371–81. [Google Scholar]

- Denzey Lewis, Nicola. 2013. Roses and Violets for the Ancestors Gifts to the Dead and Ancient Roman Forms of Social Exchange. In The Gift in Antiquity. The Ancient World. Comparative Histories. Edited by Michael L. Satlow. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 122–36. [Google Scholar]

- Denzey Lewis, Nicola. 2016. Memory in Late Roman Mortuary Spaces. In Memory in Ancient Rome and Early Christianity. Edited by Karl Galinsky. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 263–85. [Google Scholar]

- Dunbabin, Katherine M. D. 1978. The Mosaics of Roman North Africa: Studies in Iconography and Patronage. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elsner, Jaś. 1995. Art and the Roman Viewer: The Transformation of Art from the Pagan World to Christianity. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elsner, Jaś. 2007. Roman Eyes: Visuality and Subjectivity in Art and Text. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Erhart, Katherine Patricia. 1979. Tombs 79-2 and 79-3 Final Report. Unpublished report, Archaeological Exploration of Sardis. [Google Scholar]

- Feraudi-Gruénais, Francisca. 2015. The Decoration of Roman Tombs. In A Companion to Roman Art. Edited by Barbara E. Borg. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, pp. 429–51. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, Clive. 1976. Byzantine and Turkish Sardis. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, Clive. 1979. The Fabricenses Ducenarii of Sardis. Zeitschrtfifiir Papyrologie und Epigraphik 35: 279–83. [Google Scholar]

- Gadbery, Laura. 1993. Roman wall-painting at Corinth: new evidence from east of the Theater. In The Corinthia in the Roman Period: Including the Papers Given at a Symposium Held at The Ohio State University on 7–9 March, 1991. Edited by Timothy E. Gregory. Ann Arbor: Journal of Roman Archaeology, pp. 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, Regina. Forthcoming. Funerary Imagery and Iconography. In Oxford Handbook of Imagery and Iconography. Edited by Lea Cline and Nathan Elkins. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Goodenough, Erwin R. 1965. Jewish Symbols in the Greco-Roman Period. New York: Pantheon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Grabar, Oleg. 1992. The Mediation of Ornament. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greenewalt, Crawford H., Jr. 1977. The Twentieth campaign at Sardis 1977. Rivista di Archeologia 2: 105–8. [Google Scholar]

- Greenewalt, Crawford H., Jr. 1978. The Sardis Campaign of 1976. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 229: 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenewalt, Crawford H., Jr. 1979. The Sardis Campaign of 1977. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 233: 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenewalt, Crawford H., Jr., and Machteld J. Mellink. 1977. Archaeology in Asia Minor. American Journal of Archaeology 81: 308–10. [Google Scholar]

- Greenewalt, Crawford H., Jr., Andrew Ramage, Donald G. Sullivan, Kubilây Nayir, and Atilla Tulga. 1983. The Sardis Campaigns of 1979 and 1980. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 249: 3–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenewalt, Crawford H., Jr., Christopher Ratté, and Marcus L. Rautman. 1995. The Sardis Campaigns of 1992 and 1993. Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research 52: 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hanfmann, George M. A. 1952. The Season Sarcophagus in Dumbarton Oaks. 2 vols. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hanfmann, George M. A. 1960. Excavations at Sardis, 1959. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 157: 8–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanfmann, George M. A. 1962. The Fourth Campaign at Sardis (1961). Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 166: 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanfmann, George M. A. 1970. The Eleventh and Twelfth Campaigns at Sardis (1968, 1969). Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 199: 7–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanfmann, George M. A. 1972. Letters from Sardis. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hanfmann, George M. A. 1981. A Painter in the Imperial Arms Factory at Sardis. American Journal of Archaeology 85: 87–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanfmann, George M. A., and W. E. Mierse. 1983. Sardis From Prehistoric to Roman Times: Results of the Archaeological Exploration of Sardis 1958–1975. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hanfmann, George M. A., and Jane C. Waldbaum. 1975. A Survey of Sardis and the Major Monuments Outside the City. Sardis R1. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, Donald P. n.d. Peacock Tomb. Unpublished report, Archaeological Exploration of Sardis.

- Hemans, Caroline Jane. 1987. Late Antique Painting from Stobi, Yugoslavia. Ph.D. dissertation, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Hölscher, Tonio. 2004. The Language of Images in Roman Art. Translated by Anthony Snodgrass, and Annemarie Künzl-Snodgrass. with a Foreword by Jaś Elsner. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Mark Joseph. 1999. Pagan-Christian Burial Practices of the Fourth Century: Shared Tombs? In Christianity and Society: The Social World of Early Christianity. Edited by Everett Ferguson. New York: Garland Publishing Inc., pp. 385–407. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Richard. 1987. Burial Customs of Rome and the Provinces. In The Roman World. Edited by John Wacher. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, pp. 812–37. [Google Scholar]

- Kay, N. M. 2015. Ausonius: Epigrams. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, David, and Julie Kennedy. 1998. The Twin Towns and the Region. In The Twin Towns of Zeugma on the Euphrates: Rescue Work and Historical Studies. Edited by David Kennedy. Portsmouth: Journal of Roman Archaeology, pp. 30–59. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, Henry. 1987. Earth and Ocean: The Terrestrial World in Early Byzantine Art. University Park: State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maguire, Henry. 1990. Garments Pleasing to God: The Significance of Domestic Textile Designs in the Early Byzantine Period. Dumbarton Oaks Papers 44: 215–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, Eunice Dauterman, Henry Maguire, and Maggie J. Duncan-Flowers. 1989. Art and Holy Powers in the Early Christian Church. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Majewski, Lawrence J. 1970. Report on the Present Status of The Sardis Mosaic and Wall Painting: Activities and Other Work from June 28 to August 1. Unpublished report, Archaeological Exploration of Sardis. [Google Scholar]

- Majewski, Lawrence J. 1973. Report on the Study of Wall Paintings and Mosaics at Sardis: August 1 to September 21. Unpublished report, Archaeological Exploration of Sardis. [Google Scholar]

- Majewski, Lawrence J. 1977. Report on the Conservation and Technical Study of the Wall Painting in the Tomb of Chrysanthios—Tomb 76.1, July 1–August 9. Unpublished report, Archaeological Exploration of Sardis. [Google Scholar]

- Mellink, Machteld J. 1977. Archaeology in Asia Minor. American Journal of Archaeology 81: 289–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaeli, Talila. 2004. The Pictorial Program of the Tomb near Kibbutz Or-ha-Ner in Israel. In Plafonds et Voûtes à L’époque Antique. Actes du VIIIe Colloque International de l’Association Internationale pour la Peinture Murale Antique (AIPMA) 15–19 mai 2001, Budapest–Veszprém. Edited by Borhy L. avec la collaboration de Sylvia Palágyi et de Myrtill Magyar. Budapest: Pytheas Publishing, pp. 37–76. [Google Scholar]

- Mitten, David Gordon. 1980. House of Bronzes 1980: Final Report. Unpublished report, Archaeological Exploration of Sardis. [Google Scholar]

- Noy, David. 2004. Where were the Jews of the Diaspora buried? In Jews in a Graeco-Roman World. Edited by Martin Goodman. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 75–90. [Google Scholar]

- Pencheva, Angela. 2017. An Interpretation of the ‘Wreath’ in the Context of the Hellenistic Macedonian and Thracian Funerary Mural Painting. In Actes du XIIe Colloqie de l’Association Internationale Pour la Peinture Murale Antique (Athens 16–20 September, 2013). Edited by Eric Moormann. Leuven: Babesch, pp. 179–84. [Google Scholar]

- Platt, Verity. 2012. Framing the Dead on Roman Sarcophagi. RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 61: 213–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rautman, Marcus. 2011. Sardis in Late Antiquity. In Archaeology and the Cities of Asia Minor in Late Antiquity. Edited by Ortwin Dally and Christopher Ratté. Ann Arbor: Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, University of Michigan. [Google Scholar]

- Rostovtzeff, Michael Ivanovitch. 1919. Ancient Decorative Wall-Painting. Journal of Hellenic Studies 39: 144–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostovtzeff, Michael Ivanovitch. 2004. La Peinture Décorative Antique En Russie Méridionale: Saint-Pétersbourg 1913–1914. Volume 1: Texte, Description Et Étude Des Documents. Volume 2: 112 Planches. Mémoires De L’académie des Inscriptions Et Belles-Lettres, Xxviii. Paris: Académie Des Inscriptions Et Belles-lettres. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, Vanessa. 2010. Late Roman Wall Painting at Sardis. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Rousseau, Vanessa. 2014. Paradisiacal Tombs and Architectural Rooms In Late Roman Sardis: Period Styles And Regional Variants. In Actes du XIe Colloqie de l’Association Internationale pour la Peinture Murale Antique. (Ephesos 13–17 September, 2010). Edited by Norbert Zimmermann. Vienna: Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, pp. 193–98. [Google Scholar]

- Rozenberg, Silvia. 1996. The wall paintings of the Herodian Palace at Jericho. In Judaea and the Greco-Roman World in the time of Herod in the Light of Archaeological Evidence: Acts of a Symposium Organized by the Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem and the Archaeological Institute, Georg-August-University of Göttingen at Jerusalem, November 3rd–4th 1988. Edited by Klause Fittschen and Gideon Foerster. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 121–38. [Google Scholar]

- Scheller, Robert Walter Hans Peter. 1995. Exemplum: Model-Book Drawings and the Practice of Artistic Transmission in the Middle Ages (ca. 900-ca. 1470). Translated by Michael Hoyle. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt-Colinet, Andreas. 1996. East and West in Palmyrene Pattern Books. In Palmyra and the Silk Road: International Colloquium, Palmyra, 7–11 Avril 1992. Damascus: Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums, pp. 417–23. [Google Scholar]

- Shear, Theodore Leslie. 1922. Sixth Preliminary Report on the American Excavations at Sardes in Asia Minor. American Journal of Archaeology 26: 389–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shear, Theodore Leslie. 1927. A Roman Chamber-Tomb at Sardis. American Journal of Archaeology 31: 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thébert, Yvon. 1987. Private Life and Domestic Architecture in Roman Africa. In A History of Private Life I. from Pagan Rome to Byzantium. Edited by Paul Veyne. Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, pp. 313–410. [Google Scholar]

- Toynbee, Jocelyn M. C. 1971. Death and Burial in the Roman World. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Toynbee, Jocelyn M. C. 1973. Animals in Roman Life and Art. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Valeva, Julia. 1980. Sur certaines particularités des hypogées paléochrétiens des terres thraces et leurs analogue en Asie Mineure. Anatolica 7: 117–50. [Google Scholar]

- Volp, Ulrich. 2002. Tod Und Ritual in Den Christlichen Gemeinden der Antike. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Von Hesberg, Henner, Christiane Nowak, and Ellen Thiermann. 2015. Religion and Tomb. In A Companion to the Archaeology of Religion in the Ancient World. Edited by Rubina Raja and Rüpke Jörg. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell, pp. 235–49. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, M. 1994. The Organisation of Jewish Burials in Ancient Rome in the Light of Evidence from Palestine and the Diaspora. Zeitschrift Für Papyrologie Und Epigraphik 101: 165–82. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, Norbert. 2015. Catacombs and the Beginnings of Christian Tomb Decoration. In A Companion to Roman Art. Edited by Barbara E. Borg. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, pp. 452–70. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, Norbert, Sabine Ladstätter, and Mustafa Büyükkolancı. 2011. Wall Painting in Ephesos from the Hellenistic to the Byzantine Period. Istanbul: Ege Yayınları. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The site of Sardis in Western Anatolia was historically important from the Lydian through the Late Roman and Byzantine periods, and the history and population of Sardis reflected the multicultural quality of the Roman empire. The Harvard–Cornell Archaeological Exploration of Sardis has exposed remains of public and private buildings and tombs from all eras of occupation. |

| 2 | For a discussion of dating the phases of the city wall, see (Rautman 2011, pp. 11–12). |

| 3 | A number of cemeteries have been identified along with reuse or repurposing of sites within the city. For an overview of these areas, see (Hanfmann and Mierse 1983, pp. 204–10). |

| 4 | This is, admittedly, difficult to quantify in the absence of much archaeological or epigraphic evidence indicating religious belief, but Johnson makes it clear that burial was more commonly based on kinship or collegial ties (Johnson 1999, pp. 402–6). Similarly, Noy and Williams both demonstrated that Jewish burials in Rome were interspersed with those from other faiths and in general influenced more by broader Roman culture than a governing Jewish body or process (Noy 2004; Williams 1994, pp. 179–82), and Cormack notes that the funerary inscriptions of Roman Asia Minor, while revealing social status, etcetera, rarely reveal religious beliefs or hopes for the afterlife (Cormack 1997, p. 151). |

| 5 | For patterns or model books, see (Scheller 1995; Schmidt-Colinet 1996). |

| 6 | The pigments, not soluble in water, probably had lime plaster as a binding medium mixed with pigment and applied to a wetted wall. The pigments used include lime white, carbon black, light and dark red earth, yellow ochre, umbers, green earth, and granular Egyptian blue (Majewski 1970, p. 55). |

| 7 | Red framing of edges and dado zone are common in tombs elsewhere, including those from the upper city necropolis at Ephesus dated from the second-early fourth centuries (Zimmermann et al. 2011, pp. 143–46). |

| 8 | I have only found dado-level trident, candelabra or rinceaux designs in tombs at Sardis, but they are not uncommon in domestic settings of the Roman east from the first c. B.C.E. to the fourth century. Alix Barbet compiled examples from a number of Roman sites that nicely illustrate the evolution of the candelabra-type volute into a more geometric trident (Barbet 2005, p. 201, Figure 113). See also examples from Masada (Rozenberg 1996) and Corinth (Gadbery 1993, p. 55). |

| 9 | A few have longish tails suggesting peahens, natural partners for the peacocks nearby. The other, more compact and rounder, birds are probably doves or pigeons. The birds in Terrace House 2 at Ephesus include invented varieties (Zimmermann et al. 2011, pp. 133–35). |

| 10 | On the Via Triumphalis (Borg 2013, Figure 40). |

| 11 | Only a few letters survived from the vault (Greenewalt 1979, p. 5). |

| 12 | Hemans pointed out that the Chrysanthios tomb shows a familiarity with current styles and techniques, and (assuming that the deceased did at least some of the painting here) suggests that Chrysanthios had painted on plaster before (Hemans 1987, p. 164). See also (Foss 1979). |

| 13 | In addition to functioning as perpetual offerings to the deceased, wreaths were also pre-Christian symbols of special status later associated with immortality and then eternal life in the Christian context. For example, St. Paul speaks of the “imperishable wreath” granted to baptized Christians who succeed to eternal life. I Corinthians 9: 24–27. Goodenough describes the wreath as enclosing and thus protecting and sanctifying objects for pagans and probably for Jews and Christians as well (Goodenough 1965, pp. 42, 62). See also Pencheva on the wreath as indicator of ritual or change in status in Hellenistic Thrace (Pencheva 2017). |

| 14 | A notable exception is the Iznik Tomb, dated to the first third of the fourth century (Barbet 2007, p. 138). |

| 15 | Morey also notes that no Constantinian monograms antedate 300 C.E. (Butler 1922, p. 181). |

| 16 | For example, the head at Abila that may represent the deceased or a deity (Barbet and Vibert-Guigue 1994, p. 170). |

| 17 | For example, Tomb B1 at Anamur includes portraits of the Seasons (Alföldi-Rosenbaum 1971, pp. 112–14), and several vaults in Isola Sacra tombs have personifications of the seasons in their corners (Calza 1940, pp. 141–42, Figures 67 and 68). Other examples include the cubiculum of the Seasons in the catacomb of SS. Pietro and Marcellino (Bisconti 2002, p. 97, Figure 109). For Seasons on marble reliefs and sarcophagi, see (Hanfmann 1952, p. 125ff). |

| 18 | Dunbabin argues that the God of the Year was added to Season images as a way to reinvigorate the now mundane images. She further argues that patrons chose this imagery as way to attract the bounty represented (Dunbabin 1978, pp. 158–61, 165). |

| 19 | As Maguire argues for personifications of Ge or Earth (Maguire 1990, p. 217). |

| 20 | Even in the pre-Christian period, wine was associated with blood and understood as the element that separates the dead and the living. Similarly, the appropriateness of vines for burial is also noted in Petronius, when Trimalchio asks his family to grow vines and fruit trees around his burial (Petronius, Satyricon 71, 11–12; Michaeli 2004, pp. 59–60; Cumont 1942, p. 491). |

| 21 | See Appendix A.8; grave goods include a coin of Valentinian II (375-92 C.E.) (Greenewalt et al. 1983, pp. 24–25). |

| 22 | The corner flourishes are reminiscent of the domestic painting in MMS room 2 at Sardis. |

| 23 | Romans associated the dove with Venus, who is by extension a symbol of everlasting beauty and love. The dove of course became a symbol of the soul at peace early in the Christian period (Toynbee 1973, p. 259). |

| 24 | In the catacombs, tombs were roughed out and painted later, but the consistency of the majority of Sardis’s painting suggests largely contemporary decoration. |

| 25 | Valeva noted that the hypogea of Asia Minor have more abundant floral designs, while Thracian examples prefer architectonic illusionism characteristic of the Constantinian era. Valeva also notes that hypogea with built-in steps are found in Greece as well as Asia Minor, but in Thrace, doors are built into the lateral walls (Valeva 1980, pp. 119, 125). |

| 26 | For Alaşehir–Philadelphia, see (Mellink 1977, Figure 37); for Perge, see (Deleman 2008, Figures 1 and 2); for Anamur, see (Alföldi-Rosenbaum 1971); for Zeugma, see (Kennedy and Kennedy 1998); for Ephesus, see (Zimmermann et al. 2011). |

| 27 | Seven Sleepers is dated based on analogy, inscription letter forms, and textual formulae to the third century C.E., as is much of Hanghäuser 2 (Zimmermann et al. 2011, p. 158). |

| 28 | The only evidence for the freefield floral style at Sardis outside of tombs is a report indicating that fragments (now lost) very similar to the Peacock tomb came from an apse buttress wall of the fourth-century church EA and a few fragments from the Late Antique Wall and sector MMS 01.1. The fragments from the Late Antique Wall and MMS 01.1 are from fill, so the original context is unknown. On both fragments, the freefield design is painted on a c. 4 cm layer of plaster on top of an earlier layer of painted plaster. Since it seems highly unlikely that a tomb would have been redecorated, these may well have come from a domestic context and perhaps other examples will be revealed in the future (Rousseau 2010, cat. PB2, Figures 169, 159 and 160; Majewski 1973). Additionally, both funerary and domestic wall painting styles at Sardis lag behind Ephesus by about a century. For example, the third century funerary painting at Ephesus parallels Sardis’ tombs from the fourth century, and Sardis’s fifth-sixth century domestic painting resembles the fourth century Hanghauser 1 painting at Ephesus (Rousseau 2010, 2014). |

| 29 | Rostovtzeff argued that this “freefield” style (his “Floral style”) was derived from carpets decorating nomadic tents. He documents this style across the ancient world beginning in the first–second century C.E. in both painting and mosaic, and he connects it to a Ptolemaic revival of ancient Egyptian art, also noting New Kingdom tombs at Sheikh Abd-el-Gourna near Thebes and domestic paintings at Amarna (Rostovtzeff 1919, pp. 151, 160–62). |

| 30 | Clarke suggests that floral imagery has less to do with paradise than a luxurious life (Clarke 2003, pp. 110, 207). |

| 31 | Note also John Clarke’s “Tapestry Manner” (active from c. 250 B.C.E.-45 C.E.) among Fourth Style paintings, which borrowed compositions and motifs from carpets, arranging elements as flat frames on the wall surface (Clarke 1991, pp. 166–70). Additionally, references to the use of textiles in the home as prestige decoration became increasingly common in literary and visual sources from the fourth century forward, and it is clear that textiles were used commonly as curtains or doors as well as cushions and throws (Thébert 1987, pp. 388–89; Maguire et al. 1989, pp. 45–47). |

| 32 | The fact that motifs of animal and plant life (frequently including fruit) were meant to summon prosperity is proven by accompanying inscriptions on textiles, such as the invocation “flourish!” on one example and “EUPHORI” on a textile with a fruit-covered tree at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts (Maguire 1990, p. 217, Figure 8, p. 224). |

| 33 | Rostovtzeff notes examples of painted textiles on tomb vaults from Alexandria to South Russia and the Flavian Palace on the Palatine (Rostovtzeff 1919, p. 148), and Bisconti likens catacomb ceiling design to tents (Bisconti 2002, pp. 94–95). |

| 34 | See (Elsner 1995, pp. 77–78) on the function of the house as a rhetorical device. |

| 35 | The peacock was associated with immortality due to the annual shedding and regrowth of its feathers as well as the belief that its flesh did not decay (a theory tested by St. Augustine, De Civitate Dei, 21.4). By the late Hellenistic era, peacocks were associated with Dionysos and Juno, and apotheosis, used, for example, on coins minted to commemorate dead empresses (Maguire 1987, p. 39). Imperial poetry and literature associate peacocks and vegetal decoration with Elysium (Feraudi-Gruénais 2015, p. 443). In the Christian era, George of Pisidia (Hexaemeron, 1245–92) and Gregory of Nazianzus (Homilia XXVIII, 24) praised the peacock as the best of earthly creation, though it could also symbolize resurrection on Christian funerary monuments (Maguire 1987, pp. 39–40, n. 53–55). Dunbabin stresses context for determining the bird’s significance. For example, the earliest examples of peacocks in mosaics appear in Dionysiac cult contexts, but when not accompanied by specifically Dionysiac imagery, such as torch-bearing erotes, the peacock simply represents beneficence, prosperity, and fertility (Dunbabin 1978, pp. 167–69). |

| 36 | Feraudi-Gruénais applies the idea of “supra-natural” imagery transcending the natural world to “landscapes that seem to portray neither reality nor myth” (Feraudi-Gruénais 2015, p. 443). |

| 37 | Connerton and Davies outline the role of commemorative rites as expressions of identity that reaffirm social ties and continuity with the past (Connerton 1989, pp. 41–71; Davies 2002). |

| 38 | Denzey Lewis describes gift giving as a way to “redefine or reinscribe social relations among the living” (Denzey Lewis 2013, p. 124) and notes that offerings may represent the performative act of making or offering, rather than the deceased’s “direct relationship with the object.” (Denzey Lewis 2013, pp. 127–28). See also (Gee forthcoming). |

| 39 | Epigraphic sources also reference honoring the birthday of the deceased with gifts of roses in perpetuity. CIL V. 7454/ILS 8342; CIL V. 4489; CIL V. 7906/ILS 8374; CIL VI. 96.26; CIL X. 5835; Epigraphica 52 (1990) 171–74 (Carroll 2006, p. 42, n. 60). Jones notes that the literary references for these festivals date primarily to the upper classes of the first century B.C.E. and the first century C.E., but archaeological remains suggest widespread practice on some scale among all classes and into the Christian period (Jones 1987, pp. 813–14). |

| 40 | Barbet also notes that the earliest examples of the scattered flowers come from first century lararia at Pompeii, with funerary examples appearing by the early second century at Som (Barbet 2014, pp. 201–3; Von Hesberg et al. 2015, p. 246). |

| 41 | Compare, for example, the effect of flowers thrown through the Pantheon’s oculus at Pentecost. |

| 42 | Denzey Lewis describes tombs as “… ‘memory theatres’—space deliberately constructed in order to provoke, organize, broadcast and sow memories in the minds of visitors” (Denzey Lewis 2016, p. 267). See also (Gee forthcoming) on funerary imagery and iconography as well as the relationship between the dead and the living. |

| 43 | See (Volp 2002, p. 268; Denzey Lewis 2016, p. 267), among others. |

| 44 | An epitaph of Ausonius encourages adding roses to ashes and suggests an association with eternal spring and thus life beyond the grave (Kay 2015, no. 8, p. 85; Toynbee 1971, p. 63); additionally, epitaphs often mention the desire of the deceased for his or her ashes to transform into violets or roses (e.g., Servius En.: V, 79: VI, 221), and CIL: IX, 3184 states that “this flower is Flavia’s body” (Michaeli 2004). |

| 45 | Steps were not documented in the HoB and Pactolus Cliff hypogea, but this is likely due to speedy excavation or the happenstance of preservation. |

| 46 | Tomb 79.1, the only unrobbed hypogeum, contained two bodies that were either buried simultaneously or within a generation of one another; and the “Peacock tomb” contained the body of an adult in a recessed “sarcophagus” depression in the floor along with dispersed bones from other (presumably later) burials. |

| 47 | Cepotaphia are documented elsewhere by (Feraudi-Gruénais 2015, p. 444; Toynbee 1971, p. 97). |

| 48 | See also (Platt 2012, p. 220). |

| 49 | For example, Elsner presents the ideas that illusionistic Roman wall paintings (1) give the viewer a piece of the world imitated; or (2) deny the viewer the world imitated because it is false. The truth, according to Elsner, is that the viewer’s relationship with painting is subjective, and the viewer’s desires and responses move across a continuum between these two extremes (Elsner 1995, pp. 74–75). See also (Elsner 1995, 2007; Hölscher 2004). |

| 50 | Please note that the T1–T12 designations come from (Rousseau 2010). |

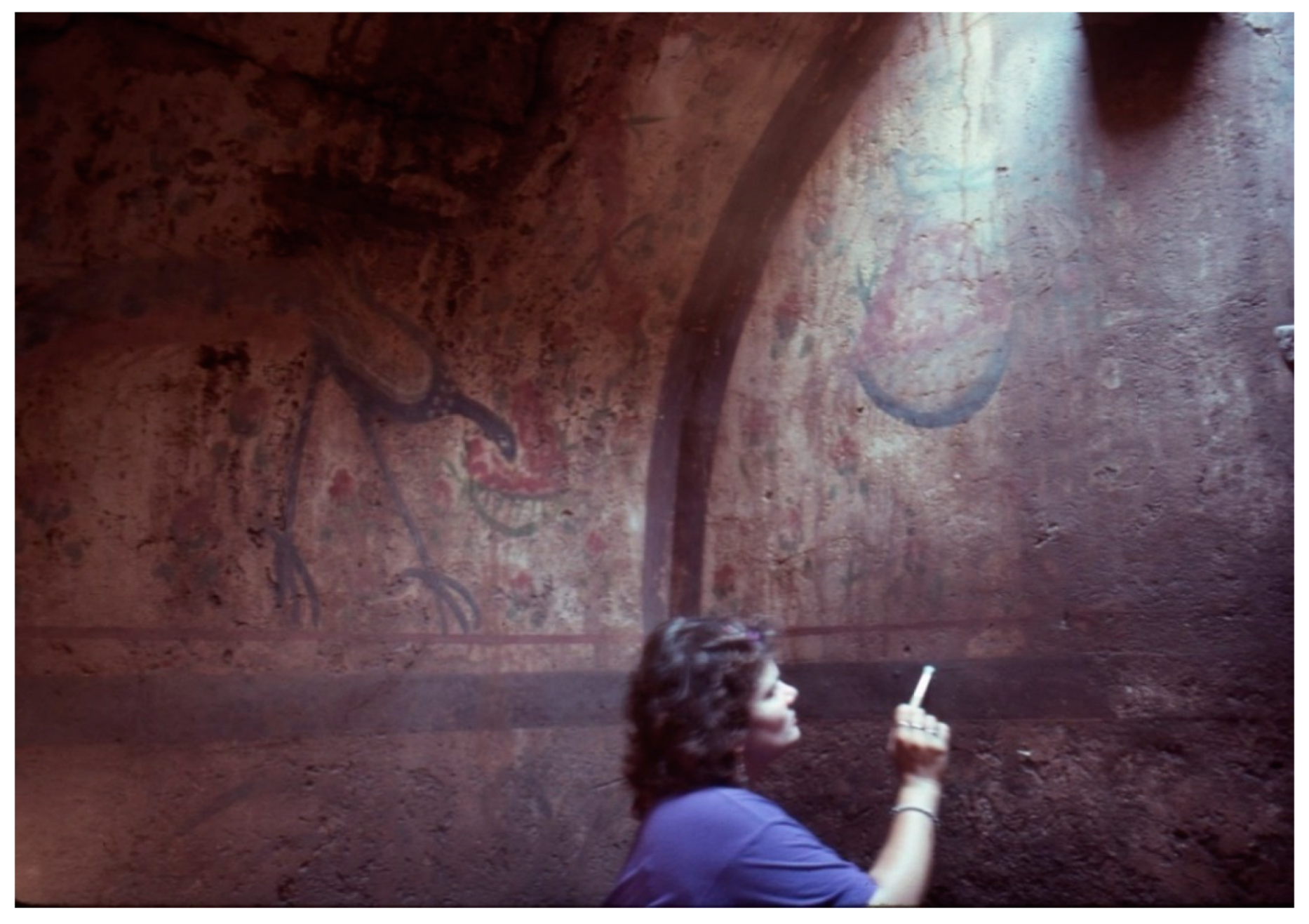

| 51 | The Chrysanthios Tomb (Tomb 76.1) was discovered in 1976 (Greenewalt and Mellink 1977, pp. 308–10, Figure 19; Greenewalt 1978, pp. 61–64, Figures 5–7), then excavated in 1977 (Greenewalt 1979, pp. 4–9, Figures 3–5; Greenewalt 1977, p. 105). See also (Hanfmann 1981; Hanfmann and Mierse 1983, p. 208, no. 4, 208; Majewski 1977). |

| 52 | The arc of the vault is greater at the entrance end (angle more acute) and does not bond with the rest (Greenewalt 1979, p. 5). |

| 53 | Majewski report quoted in (Greenewalt 1979, p. 6). |

| 54 | Only a few letters survived from the vault (Greenewalt 1979, p. 5). |

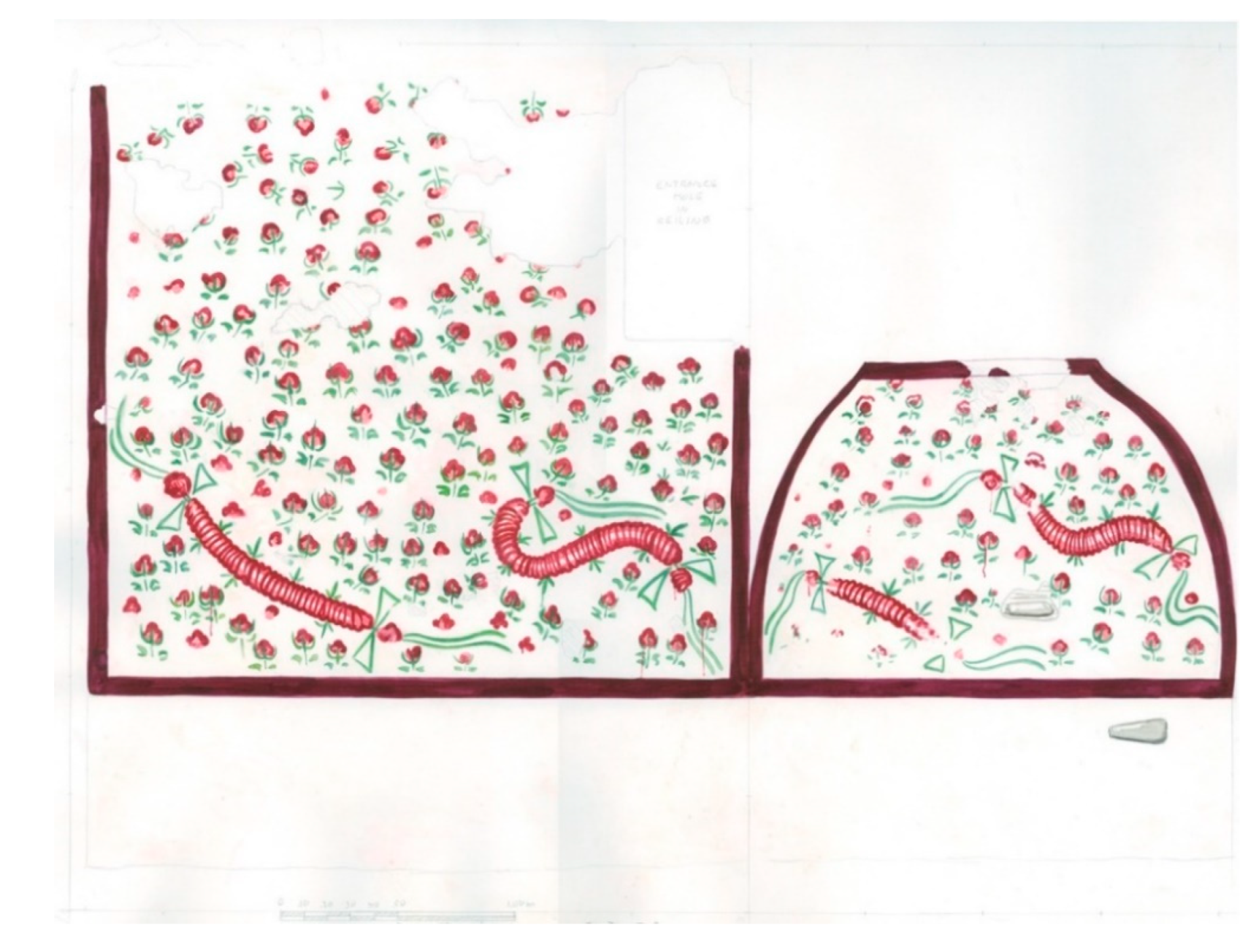

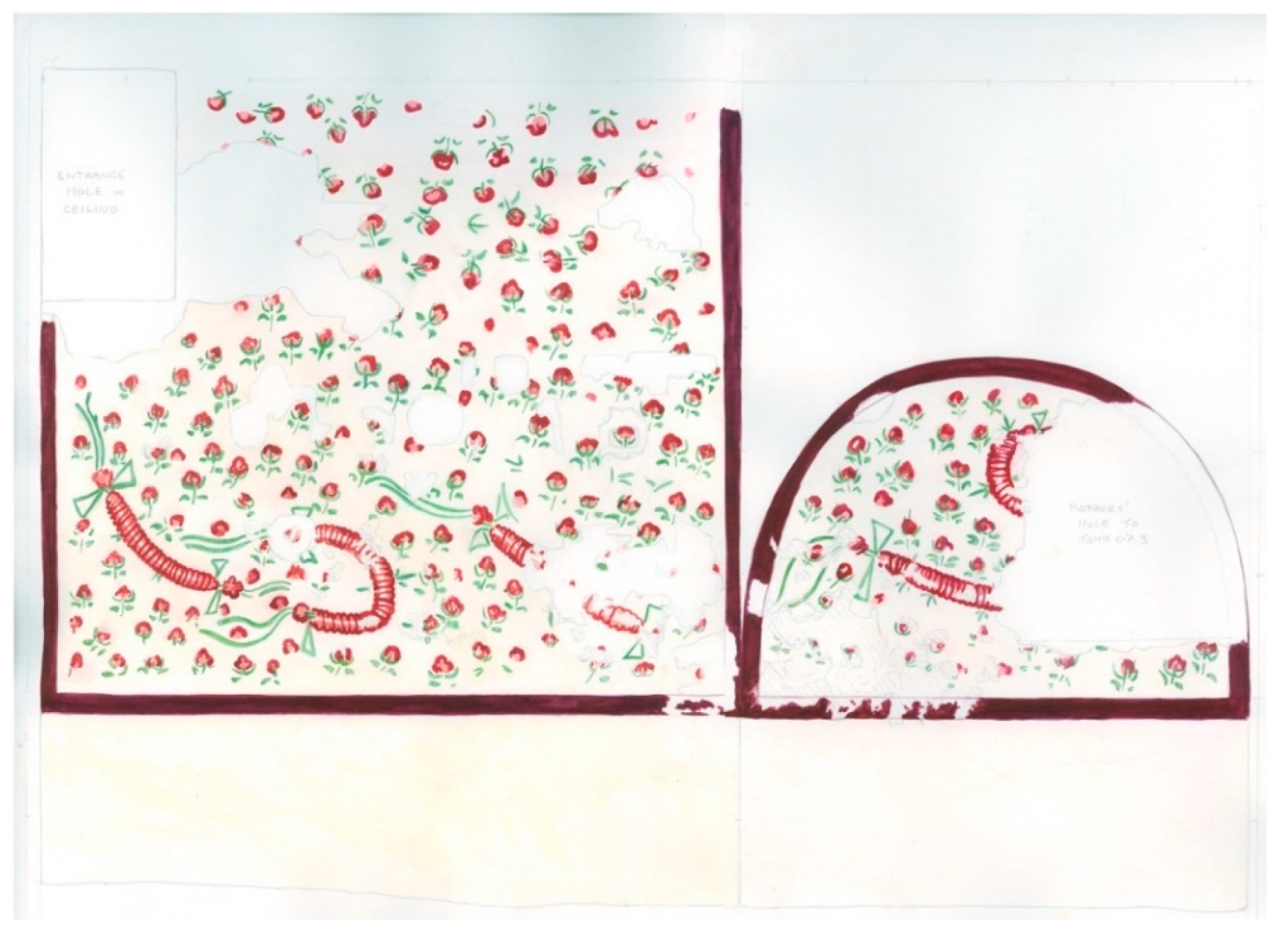

| 55 | This tomb is first mentioned in (Butler 1913, p. 478) and discussed more fully by C. R. Morey in (Butler 1922, pp. 174, 181–183, ill. 18, color pls. IV–V). The tomb was vandalized in 1913 and is now lost beneath a farmer’s field—only the paintings published in Sardis I remain. The Painted Tomb is #3 in (Hanfmann and Mierse 1983, p. 208). |

| 56 | A notable exception is the Iznik Tomb, dated to the first third of the fourth century (Barbet 2007, p. 138). |

| 57 | Morey also notes that no Constantinian monograms antedate 300 C.E. (Butler 1922, p. 181). |

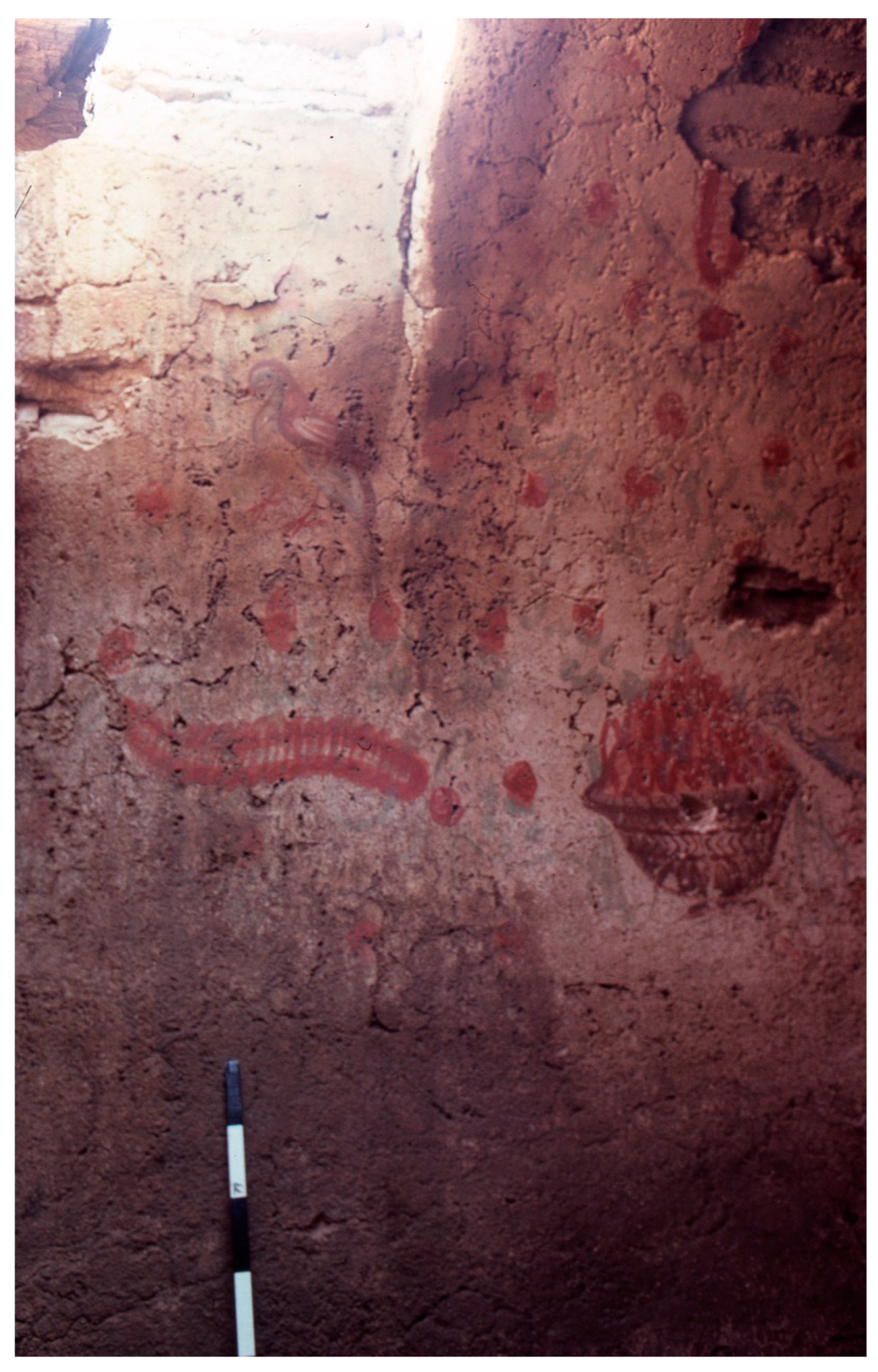

| 58 | The Peacock Tomb (Tomb 61.14) was excavated in 1961 (Hanfmann 1962, pp. 30–33, Figure 26), which is the presumed date for Donald P. Hansen’s undated “Peacock Tomb” report (Hansen n.d.). The removal of the frescoes was covered by Majewski in (Hanfmann 1970, pp. 56–58, Figures 44 and 45). See also (Hanfmann 1972, p. 89; Hanfmann and Mierse 1983, pp. 205, 207, 208, no. 7). |

| 59 | The body of an adult around 60 years of age was found in the floor along with dispersed bones from other burials. Coins found in the earth range from Honorius (393–423) to Phocas (602–610). The tile graves are graves 61.24 and 61.25 and the 60-year-old in the “sarcophagus” built into the floor is grave 61.14 (Hansen n.d., p. 1; Hanfmann and Mierse 1983, p. 208). |

| 60 | These were given catalogue numbers WP 61.1 E, WP 61.1 N and WP 61.1 S, respectively (Majewski 1970, pp. 57–58). |

| 61 | Published in (Greenewalt et al. 1995, pp. 1–3, Figure 2). |

| 62 | These tombs have not yet been published. The information is based on my observations of the paintings and (D’Angelo 2008). |

| 63 | Coin 2008.0017 is probably 3rd–4th c., and Coin 2008.0018 is a coin of Caracalla according to numismatist Jane DeRose Evans. |

| 64 | Tombs 79.2 and 79.3 were excavated during the campaign of 1979 (Greenewalt et al. 1983, p. 22, Figure 26). Tomb 79.2 is also published as the “Tomb excavated by K.P. Erhart in 1979” in (Hanfmann and Mierse 1983, p. 208, no. 9). |

| 65 | 79.2 and 79.3 were built into a hill in a stepped manner; the vault of 79.2 higher than that of 79.3. Unpainted tomb 79.3 is 2.74–2.84 m long by 1.75–1.84 m wide and 1.75 m high (Erhart 1979, p. 1). |

| 66 | Paint primarily survives on the east and west walls, and the dado band runs 0.53–0.66 m from the floor. In the upper field of each of the east and west walls, a pheasant (?) nibbles at a basket of fruit with another bird (possibly a dove on the west and a robin on the east). The birds were painted with red, green, and red-brown with touches of white, yellow, and blue. The excavator described the vault as perhaps having been decorated with a trellis or arborway in addition to the strewn flowers, but photos suggest the usual garlands or wreaths (Erhart 1979, pp. 3–4). |

| 67 | The grave goods include a bronze buckle (M79.1:8417), terracotta bowl, and two 4th century coins (Greenewalt et al. 1983, p. 22). |

| 68 | Discovered in 1922, Shear published this tomb along with watercolors by Mrs. Shear (Shear 1922, pp. 405–7, Figures 13 and 14; Shear 1927, pp. 19–25, Figures 1–3, pls. III–VI); and also in (Hanfmann and Mierse 1983, p. 207, no. 2); WP 69.2. |

| 69 | Only watercolor paintings recorded the decoration in this tomb at the time of its 1922 excavation, but a 2008 visit confirmed that the watercolors accurately captured its unusual painting style. |

| 70 | As Shear noted, these “garlands” seem to be open at the top and closed at the bottom and may well represent a bag stuffed with flowers, a carryover of Greek taenia, which also appears at Kertsch (Shear 1927, p. 21). |

| 71 | Shear dated the majority of the lamps to the first century C.E., with one “late or quasi-Christian”, and argues that the range of dates indicates reuse of the tomb and an initial construction date no later than the second century. The current location of the lamps is unclear, and comparison via the drawing published by Shear does little to narrow chronology (Shear 1927, pp. 24–25, Figure 3). |

| 72 | Tomb 79.1, found between seasons, was excavated by the Manisa museum and published in (Greenewalt et al. 1983, pp. 22–25, Figures 27–30). Tomb 79.1 is also published as the “Tomb excavated by the Manisa Museum in 1979” in (Hanfmann and Mierse 1983, p. 208). |

| 73 | Garlands are 0.53–0.66 m across (Greenewalt et al. 1983, pp. 24–25). |

| 74 | This tomb was excavated by Butler, who reported that it contained no paintings (Butler 1922, p. 128), Majewski first catalogued the frescoes in 1969 as WP 69.1 and published a note on them in (Hanfmann 1970). The tomb is published in (Hanfmann and Mierse 1983, p. 207, no. 1) and in (Hanfmann and Waldbaum 1975, pp. 59–60, Figures 59, 61, 68, 72–74). |

| 75 | The corner flourishes are reminiscent of the domestic painting in MMS room 2 at Sardis. |

| 76 | In addition, Butler excavated four vaulted and perhaps plastered tombs on the south side of the Artemis temple, which can only be tentatively dated as “early Byzantine” due to their poor state of preservation (Hanfmann and Waldbaum 1975, pp. 60, 66–67, Figures 59, 98–100; Butler 1922, p. III). |

| 77 | (Hanfmann and Waldbaum 1975, pp. 56, 58–61, Figures 59, 61, 68). See also (Hanfmann and Mierse 1983, pp. 195, 205). |

| 78 | This tomb was excavated in 1959 (Hanfmann 1960, p. 26; Hanfmann and Mierse 1983, p. 208, no. 5). |

| 79 | A coin of Justin II (565–578 C.E.) sealed between the tomb and floor of the house above gives a broad terminus ante quem, but there is every reason to date the tomb to the fourth century (Mitten 1980, pp. 8–13). |

| 80 | The 1967 Sardis conservation lab record states that little painting remained, but it was faced with muslin and cleaned in July 1964. No remains or images have survived. |

| 81 | In 1959, a landslide exposed remains in the Pactolus cliff, which proved to be from multiple periods (Hanfmann 1960, pp. 14–16, Figures 3 and 4). Both chambers were removed during the 1960 season in order to reach the Lydian levels below (Del Chiaro 1960, p. 1). |

| 82 | The two spaces were connected with their vaults at right angles to one another: A door in the north wall of LVC led into SVC, and it appears that LVC was oriented east–west and SVC north–south. The stone slabs making up the floor of each chamber covered burial pits built of stuccoed tiles (five in LVC and two in SVC). Pit 1 in LVC contained the sculpted head of a priest dated to the second half of the third century C.E. Hanfmann notes that the pits had already been opened but still contained glass and pottery (upon which he does not elaborate) (Hanfmann 1960, pp. 14–16, Figures 3 and 4). |

| 83 | According to the 1960 final report, SVC and LVC were removed in order to reach earlier levels (Del Chiaro 1960, p. 1). |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rousseau, V. Reflection, Ritual, and Memory in the Late Roman Painted Hypogea at Sardis. Arts 2019, 8, 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030103

Rousseau V. Reflection, Ritual, and Memory in the Late Roman Painted Hypogea at Sardis. Arts. 2019; 8(3):103. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030103

Chicago/Turabian StyleRousseau, Vanessa. 2019. "Reflection, Ritual, and Memory in the Late Roman Painted Hypogea at Sardis" Arts 8, no. 3: 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts8030103