High Performance Fine-Grained Biodegradable Mg-Zn-Ca Alloys Processed by Severe Plastic Deformation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

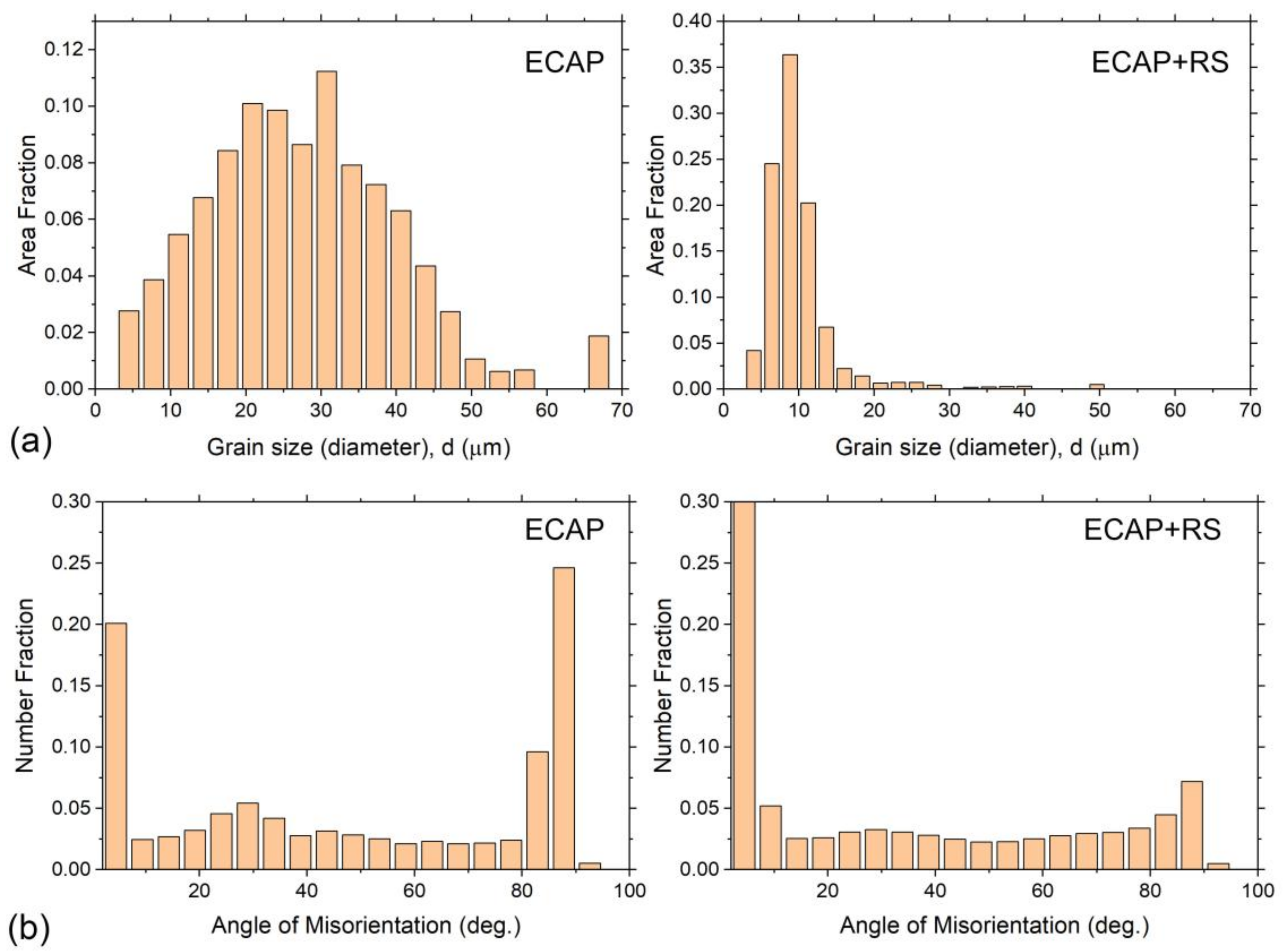

3.1. Microstructure

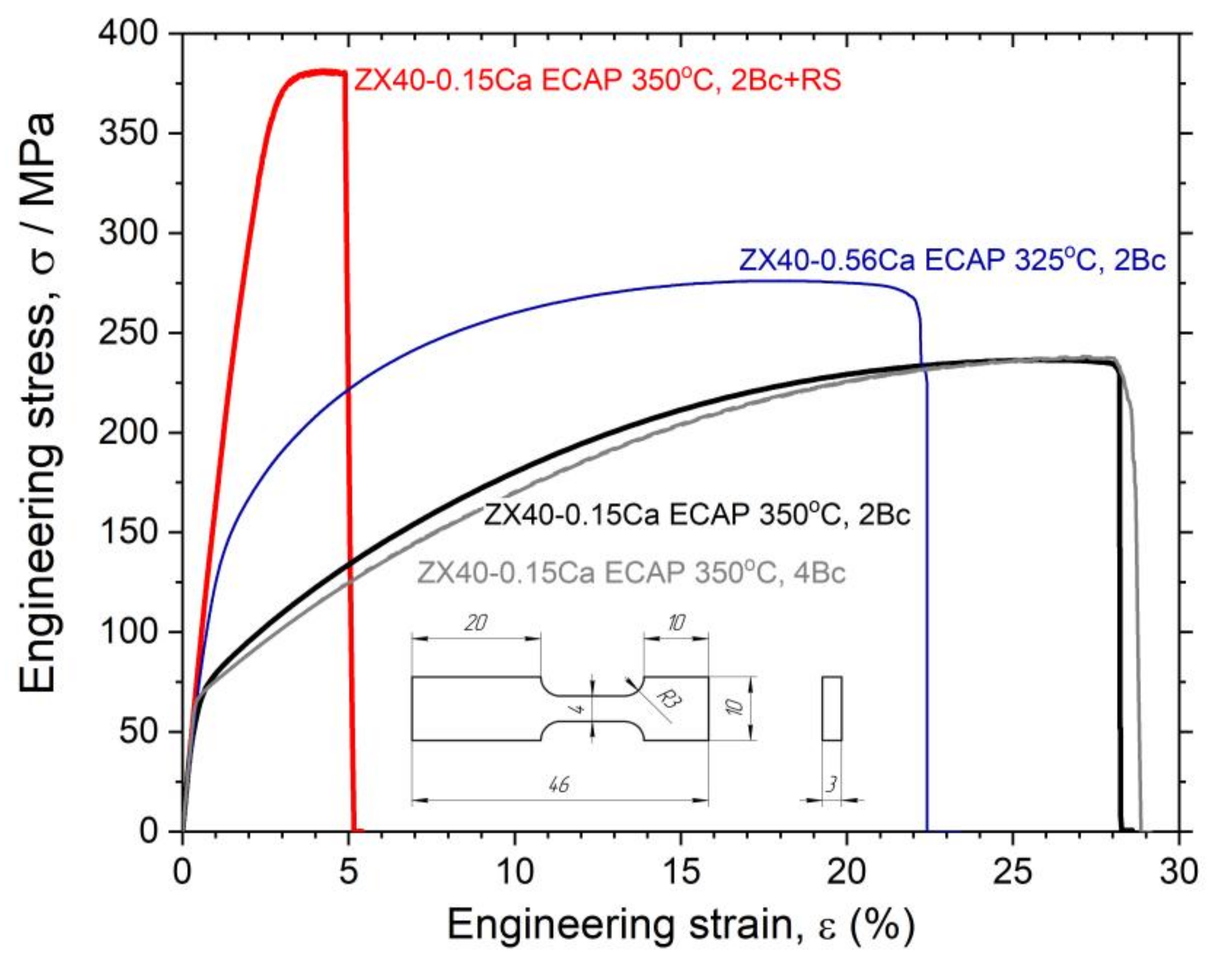

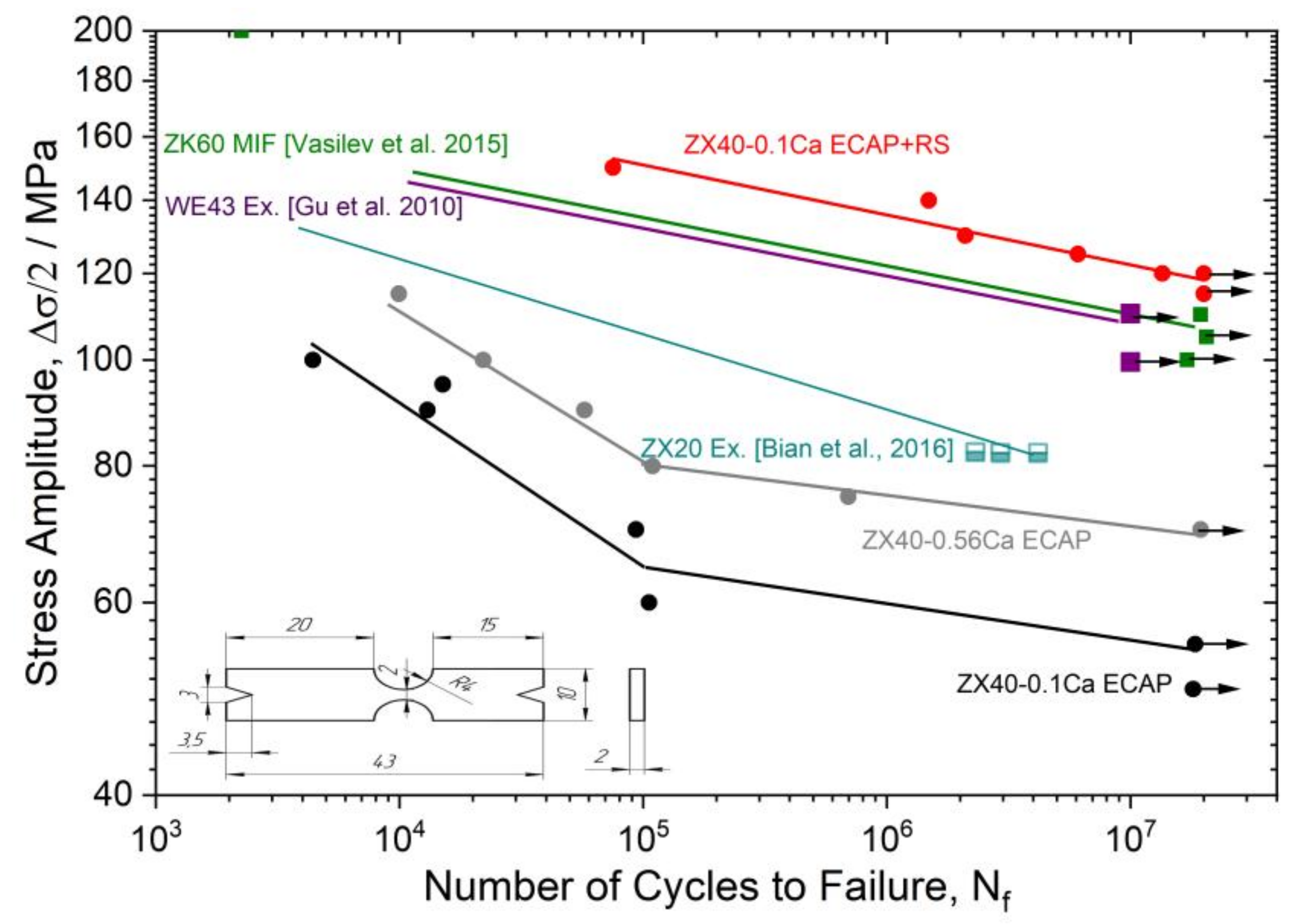

3.2. Mechanical Properties

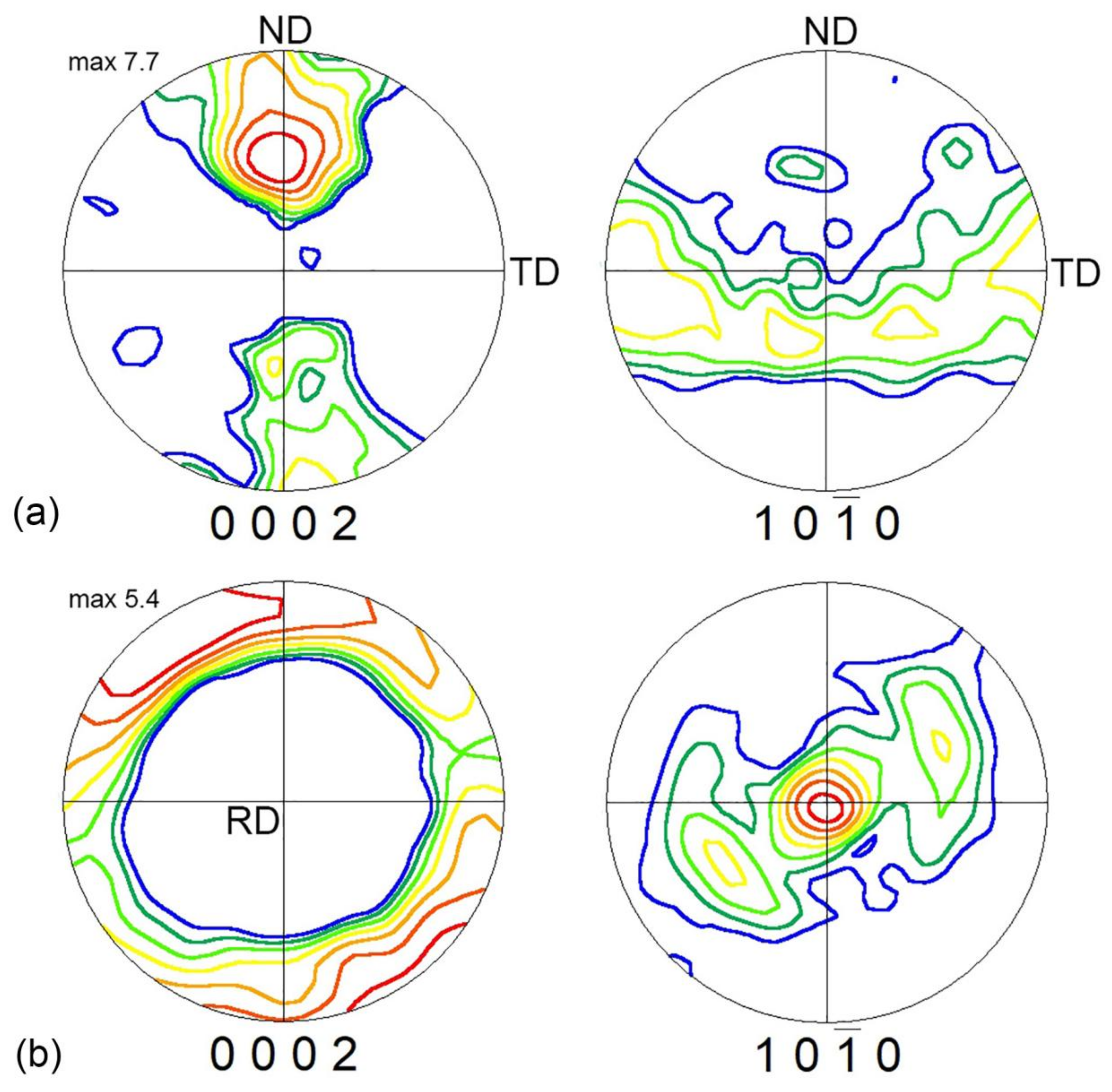

3.3. Texture Analysis

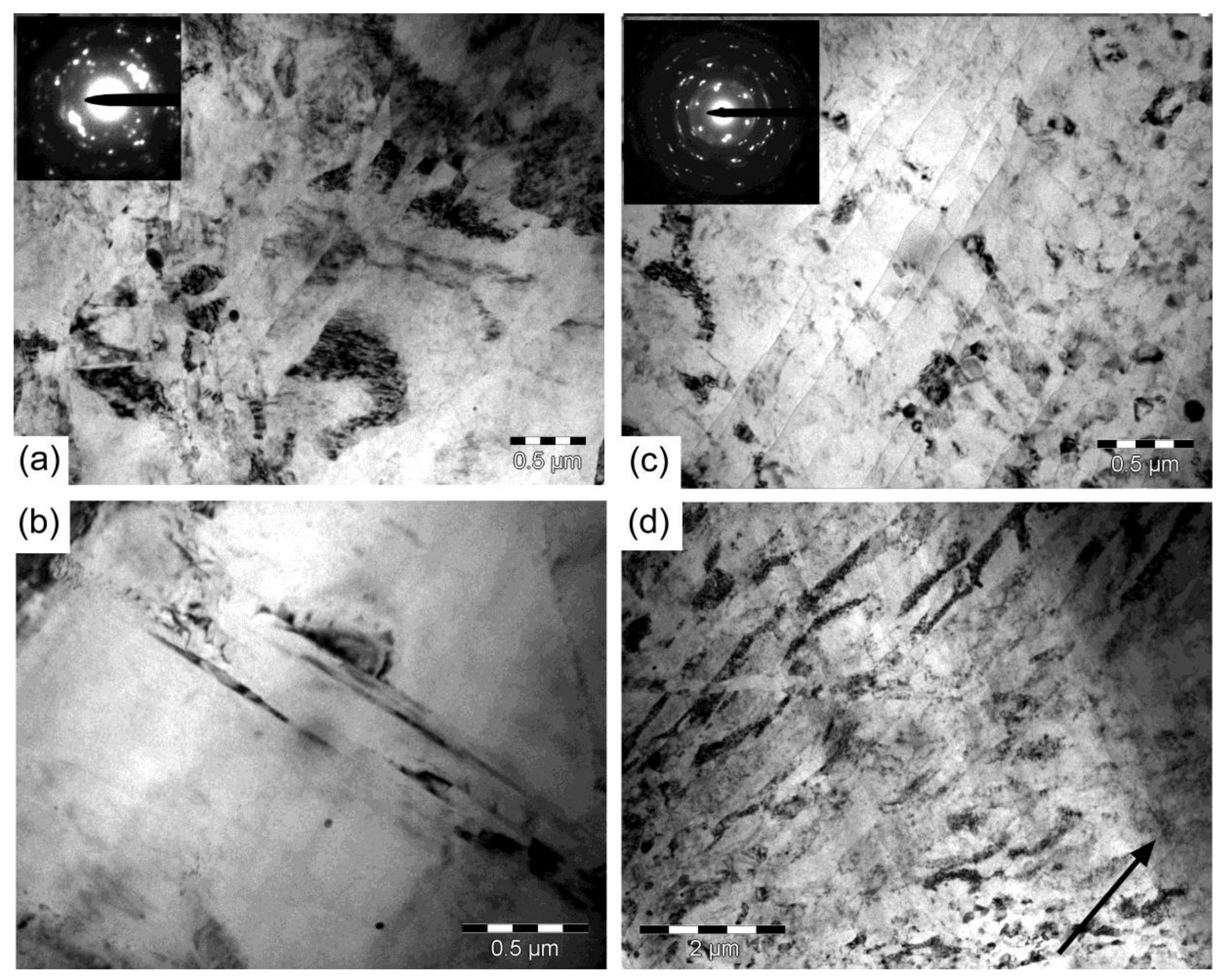

3.4. Tem Observations of the Microstructure of the Rotary Swaged Specimens

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- Hybrid SPD processing comprised of hot ECAP and cold (room temperature) rotary swaging of magnesium alloys paves a new avenue for the fabrication of nanostructured high strength alloys that benefits from a combined effect of grain refinement down to the nano-scale with dislocation strengthening and texture transformation.

- (2)

- The nominally low strength Mg Zn-Ca alloys with the fine grain microstructure obtained by hybrid processing demonstrated an excellent combination of tensile and fatigue strength (σ0.2 = 380 and σ−1 = 120 MPa, respectively), exceeding those known for most conventionally processed alloys aimed at biomedical applications, though the ductility has been compromised to some extent. This combination makes these alloys appealing for a wide range of applications where weight saving and/or biocompatibility and biodegradability are of concern.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Witte, F. The history of biodegradable magnesium implants: A review. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 1680–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erinc, M.; Sillekens, W.H.; Mannens, R.G.T.M.; Werkhoven, R.J. Applicability of Existing Magnesium Alloys as Biomedical Implant Materials; Data Archiving and Networked Services: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 209–214. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Thouas, G.A. Metallic implant biomaterials. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2015, 87, 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farraro, K.F.; Kim, K.E.; Woo, S.L.Y.; Flowers, J.R.; McCullough, M.B. Revolutionizing orthopaedic biomaterials: The potential of biodegradable and bioresorbable magnesium-based materials for functional tissue engineering. J. Biomech. 2014, 47, 1979–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, B.P.; Wang, Y.; Geng, L. Research on mg-zn-ca alloy as degradable biomaterial, biomaterials—Physics and chemistry. In Biomaterials; Pignatello, R., Ed.; InTech.: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Y.; Bradshaw, A.R.; Chiu, Y.L.; Jones, I.P. Effects of secondary phase and grain size on the corrosion of biodegradable mg-zn-ca alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2015, 48, 480–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hänzi, A.C.; Gerber, I.; Schinhammer, M.; Löffler, J.F.; Uggowitzer, P.J. On the in vitro and in vivo degradation performance and biological response of new biodegradable Mg–Y–Zn alloys. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 1824–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hänzi, A.C.; Sologubenko, A.S.; Uggowitzer, P.J. Design strategy for new biodegradable Mg-Y-Zn alloys for medical applications. Int. J. Mater. Res. 2009, 100, 1127–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, E.; Kawamura, Y.; Hayashi, K.; Inoue, A. Long-period ordered structure in a high-strength nanocrystalline Mg-1 at% Zn-2 at% Y alloy studied by atomic-resolution z-contrast stem. Acta Mater. 2002, 50, 3845–3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamura, Y.; Yamasaki, M. Formation and mechanical properties of Mg97Zn1Re2 alloys with long-period stacking ordered structure. Mater. Trans. 2007, 48, 2986–2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstetter, J.; Becker, M.; Martinelli, E.; Weinberg, A.M.; Mingler, B.; Kilian, H.; Pogatscher, S.; Uggowitzer, P.J.; Löffler, J.F. High-strength low-alloy (HSLA) Mg–Zn–Ca alloys with excellent biodegradation performance. JOM 2014, 66, 566–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstetter, J.; Martinelli, E.; Pogatscher, S.; Schmutz, P.; Povoden-Karadeniz, E.; Weinberg, A.M.; Uggowitzer, P.J.; Löffler, J.F. Influence of trace impurities on the in vitro and in vivo degradation of biodegradable Mg-5Zn-0.3Ca alloys. Acta Biomater. 2015, 23, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstetter, J.; Rüedi, S.; Baumgartner, I.; Kilian, H.; Mingler, B.; Povoden-Karadeniz, E.; Pogatscher, S.; Uggowitzer, P.J.; Löffler, J.F. Processing and microstructure–property relations of high-strength low-alloy (HSLA) Mg–Zn–Ca alloys. Acta Mater. 2015, 98, 423–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roessle, M.L.; Fatemi, A. Strain-controlled fatigue properties of steels and some simple approximations. Int. J. Fatigue 2000, 22, 495–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heywood, R.B. Designing against Fatigue of Metals; Reinhold: New York, NY, USA, 1962; p. 436. [Google Scholar]

- Estrin, Y.; Vinogradov, A. Extreme grain refinement by severe plastic deformation: A wealth of challenging science. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 782–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdon, T.G. Twenty-five years of ultrafine-grained materials: Achieving exceptional properties through grain refinement. Acta Mater. 2013, 61, 7035–7059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, V.M. Equal channel angular extrusion: From macromechanics to structure formation. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 1999, 271, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, V. Review: Modes and processes of severe plastic deformation (SPD). Materials 2018, 11, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semenova, I.P.; Salimgareeva, G.K.; Latysh, V.V.; Valiev, R.Z. Enhanced fatigue properties of ultrafine-grained titanium rods produced using severe plastic deformation. Solid State Phenom. 2008, 140, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kegg, R.L. Mechanics of the rotary swaging process. J. Eng. Ind. 1964, 86, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulstaar, M.A.; El-Danaf, E.A.; Waluyo, N.S.; Wagner, L. Severe plastic deformation of commercial purity aluminum by rotary swaging: Microstructure evolution and mechanical properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2013, 565, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Huang, A.; Gao, L.; Li, Y.; Huang, C. Promising tensile and fatigue properties of commercially pure titanium processed by rotary swaging and annealing treatment. Materials 2018, 11, 2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALkhazraji, H.; El-Danaf, E.; Wollmann, M.; Wagner, L. Enhanced fatigue strength of commercially pure Ti processed by rotary swaging. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2015, 2015, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muller, J.; Janecek, M.; Wagner, L. Influence of post-ecap TMT on mechanical properties of the wrought magnesium alloy AZ80. Mater. Sci. Forum 2008, 584, 858–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, W.M.; Huang, Y.D.; Wang, R.; Zhong, Z.Y.; Hort, N.; Kainer, K.U.; Schell, N.; Brokmeier, H.G.; Schreyer, A. Bulk and local textures of pure magnesium processed by rotary swaging. J. Mag. Alloy. 2013, 1, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gan, W.M.; Huang, Y.D.; Wang, R.; Wang, G.F.; Srinivasan, A.; Brokmeier, H.G.; Schell, N.; Kainer, K.U.; Hort, N. Microstructures and mechanical properties of pure mg processed by rotary swaging. Mater. Des. 2014, 63, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minárik, P.; Zemková, M.; Král, R.; Mhaede, M.; Wagner, L.; Hadzima, B. Effect of microstructure on the corrosion resistance of the AE42 magnesium alloy processed by rotary swaging. Acta Phys. Pol. A 2015, 128, 805–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueiredo, R.B.; Cetlin, P.R.; Langdon, T.G. The processing of difficult-to-work alloys by ecap with an emphasis on magnesium alloys. Acta Mater. 2007, 55, 4769–4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasilev, E.; Linderov, M.; Nugmanov, D.; Sitdikov, O.; Markushev, M.; Vinogradov, A. Fatigue performance of mg-zn-zr alloy processed by hot severe plastic deformation. Metals 2015, 5, 2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkland, N.T.; Birbilis, N.; Staiger, M.P. Assessing the corrosion of biodegradable magnesium implants: A critical review of current methodologies and their limitations. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado, M.C.; García-Galvan, F.R.; Barranco, V.; Feliu Batlle, S. A measuring approach to assess the corrosion rate of magnesium alloys using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. In Magnesium Alloys; IntechOpen: Londone, UK, 2017; pp. 130–159. [Google Scholar]

- Nidadavolu, E.P.S.; Feyerabend, F.; Ebel, T.; Willumeit-Römer, R.; Dahms, M. On the determination of magnesium degradation rates under physiological conditions. Materials 2016, 9, 627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.; Atrens, A. Understanding magnesium corrosion—A framework for improved alloy performance. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2003, 5, 837–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokubo, T.; Takadama, H. How useful is SBF in predicting in vivo bone bioactivity? Biomaterials 2006, 27, 2907–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, Y.; Hu, T.; Chu, P.K. Influence of test solutions on in vitro studies of biomedical magnesium alloys. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2010, 157, C238–C243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y. Magnesium Alloys as Degradable Biomaterials; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zander, D.; Zumdick, N.A. Influence of Ca and Zn on the microstructure and corrosion of biodegradable Mg–Ca–Zn alloys. Corros. Sci. 2015, 93, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhsheshi-Rad, H.R.; Hamzah, E.; Fereidouni-Lotfabadi, A.; Daroonparvar, M.; Yajid, M.A.M.; Mezbahul-Islam, M.; Kasiri-Asgarani, M.; Medraj, M. Microstructure and bio-corrosion behavior of Mg–Zn and Mg–Zn–Ca alloys for biomedical applications. Mater. Corros. 2014, 65, 1178–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Hou, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Geng, L. Mechanical properties, degradation performance and cytotoxicity of Mg–Zn–Ca biomedical alloys with different compositions. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2011, 31, 1667–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinogradov, A.; Vasilev, E.; Linderov, M.; Merson, D. Evolution of mechanical twinning during cyclic deformation of Mg-Zn-Ca alloys. Metals 2016, 6, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardim, P.M.; Solórzano, G.; Sande, J.B.V. Second phase formation in melt-spun Mg–Ca–Zn alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 381, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.-J.; Deng, K.-K.; Zhang, X.; Nie, K.-B.; Xu, F.-J. Effect of ultra-slow extrusion speed on the microstructure and mechanical properties of Mg-4Zn-0.5Ca alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2016, 677, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubok, K.; Lityńska-Dobrzyńska, L.; Wojewoda-Budka, J.; Góral, A.; Dȩbski, A. Investigation of structures in as-cast alloys from the Mg-Zn-Ca system. Arch. Metall. Mater. 2013, 58, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi, G.; Avraham, S.; Zilberov, A.; Bamberger, M. Solidification, solution treatment and age hardening of a Mg–1.6 wt.% Ca–3.2 wt.% Zn alloy. Acta Mater. 2006, 54, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasiur-Rahman, S.; Medraj, M. Critical assessment and thermodynamic modeling of the binary Mg–Zn, Ca–Zn and ternary Mg–Ca–Zn systems. Intermetallics 2009, 17, 847–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.C.; Ohkubo, T.; Mukai, T.; Hono, K. TEM and 3DAP characterization of an age-hardened Mg–Ca–Zn alloy. Scr. Mater. 2005, 53, 675–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, J.F.; Muddle, B.C. Precipitation hardening of Mg-Ca(-Zn) alloys. Scr. Mater. 1997, 37, 1475–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhsheshi-Rad, H.R.; Abdul-Kadir, M.R.; Idris, M.H.; Farahany, S. Relationship between the corrosion behavior and the thermal characteristics and microstructure of Mg–0.5Ca–xZn alloys. Corros. Sci. 2012, 64, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Charni, D.; Ishkina, S.; Epp, J.; Herrrmann, M.; Schenck, C.; Zoch, H.W.; Kuhfuss, B. Generation of Residual Stresses in Rotary Swaging Process; Dean, T.A., Qin, Y., Vollertsen, F., Yuan, S.J., Eds.; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, E. Eight routes to improve the tensile ductility of bulk nanostructured metals and alloys. JOM 2006, 58, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niendorf, T.; Canadinc, D.; Maier, H.J.; Karaman, I. The role of grain size and distribution on the cyclic stability of titanium. Scr. Mater. 2009, 60, 344–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapovok, R.; Cottam, R.; Thomson, P.; Estrin, Y. Extraordinary superplastic ductility of magnesium alloy zk60. J. Mater. Res. 2005, 20, 1375–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.-W.; Suh, B.-C.; Shim, M.-S.; Bae, J.H.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, N.J. Texture evolution in Mg-Zn-Ca alloy sheets. Met. Mat. Trans. A 2013, 44, 2950–2961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinogradov, A. Mechanical properties of ultrafine-grained metals: New challenges and perspectives. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2015, 17, 1710–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasnikov, I.S.; Estrin, Y.; Vinogradov, A. What governs ductility of ultrafine-grained metals? A microstructure based approach to necking instability. Acta Mater. 2017, 141, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.N.; Zhou, W.R.; Zheng, Y.F.; Cheng, Y.; Wei, S.C.; Zhong, S.P.; Xi, T.F.; Chen, L.J. Corrosion fatigue behaviors of two biomedical mg alloys—AZ91d and WE43—In simulated body fluid. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 4605–4613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, D.; Zhou, W.; Liu, Y.; Li, N.; Zheng, Y.; Sun, Z. Fatigue behaviors of Hp-Mg, Mg–Ca and Mg–Zn–Ca biodegradable metals in air and simulated body fluid. Acta Biomater. 2016, 41, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugmanov, D.R.; Sitdikov, O.S.; Markushev, M.V. Texture and anisotropy of yield strength in multistep isothermally forged Mg-5.8Zn-0.65Zr alloy. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2015, 82, 012099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Markushev, M.V.; Nugmanov, D.R.; Sitdikov, O.; Vinogradov, A. Structure, texture and strength of Mg-5.8Zn-0.65Zr alloy after hot-to-warm multi-step isothermal forging and isothermal rolling to large strains. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 709, 330–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogarevic, V.V.; Stephens, R.I. Fatigue of magnesium alloys. Ann. Rev. Mater. Sci. 1990, 20, 141–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Mario, C.; Griffiths, H.; Goktekin, O.; Peeters, N.; Verbist, J.; Bosiers, M.; Deloose, K.; Heublein, B.; Rohde, R.; Kasese, V.; et al. Drug-eluting bioabsorbable magnesium stent. J. Interv. Cardiol. 2004, 17, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erne, P.; Schier, M.; Resink, T.J. The road to bioabsorbable stents: Reaching clinical reality? Cardiovasc. Interv. Radiol. 2006, 29, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komai, K. 4.13—Corrosion fatigue. In Comprehensive Structural Integrity; Milne, I., Ritchie, R.O., Karihaloo, B., Eds.; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 2003; pp. 345–358. [Google Scholar]

- Hilpert, M.; Wagner, L. Corrosion fatigue behavior of the high-strength magnesium alloy AZ80. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2000, 9, 402–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliezer, A.; Gutman, E.M.; Abramov, E.; Unigovski, Y. Corrosion fatigue of die-cast and extruded magnesium alloys. J. Light Met. 2001, 1, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh Raman, R.K.; Jafari, S.; Harandi, S.E. Corrosion fatigue fracture of magnesium alloys in bioimplant applications: A review. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2015, 137, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tunold, R.; Holtan, H.; Berge, M.-B.H.; Lasson, A.; Steen-Hansen, R. The corrosion of magnesium in aqueous solution containing chloride ions. Corros. Sci. 1977, 17, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atrens, A.; Song, G.-L.; Liu, M.; Shi, Z.; Cao, F.; Dargusch, M.S. Review of recent developments in the field of magnesium corrosion. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2015, 17, 400–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullmann, B.; Reifenrath, J.; Seitz, J.-M.; Bormann, D.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A. Influence of the grain size on the in vivo degradation behaviour of the magnesium alloy LAE442. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part H: J. Eng. Med. 2013, 227, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gehrmann, R.; Frommert, M.M.; Gottstein, G. Texture effects on plastic deformation of magnesium. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2005, 395, 338–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Singh Dhinwal, S.; Suwas, S. Room-temperature equal channel angular extrusion of pure magnesium. Acta Mater. 2010, 58, 3247–3261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, S.R.; Horton, J.A.; Lillo, T.M.; Brown, D.W. Enhanced ductility in strongly textured magnesium produced by equal channel angular processing. Scr. Mater. 2004, 50, 377–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beausir, B.; Suwas, S.; Tóth, L.S.; Neale, K.W.; Fundenberger, J.-J. Analysis of texture evolution in magnesium during equal channel angular extrusion. Acta Mater. 2008, 56, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gzyl, M.; Rosochowski, A.; Boczkal, S.; Olejnik, L. The role of microstructure and texture in controlling mechanical properties of AZ31b magnesium alloy processed by i-ecap. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2015, 638, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, S.R.; Yoo, M.H.; Tome, C.N. Application of texture simulation to understanding mechanical behavior of mg and solid solution alloys containing Li or Y. Acta Mater. 2001, 49, 4277–4289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleiner, S.; Uggowitzer, P.J. Mechanical anisotropy of extruded Mg–6% Al–1% Zn alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 379, 258–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.J.; Liu, Z.Y.; Wang, E.D. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Mg–Al–Zn alloy deformed by cold extrusion. Mater. Lett. 2008, 62, 3051–3054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottstein, G.; Al Samman, T. Texture development in pure mg and mg alloy AZ31. Mater. Sci. Forum 2005, 495, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Samman, T.; Li, X. Sheet texture modification in magnesium-based alloys by selective rare earth alloying. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 528, 3809–3822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, Y.; Geng, L.; Lu, C. Effects of calcium on texture and mechanical properties of hot-extruded Mg–Zn–Ca alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2012, 539, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood Chaudry, U.; Hoo Kim, T.; Duck Park, S.; Sik Kim, Y.; Hamad, K.; Kim, J.-G. On the high formability of AZ31-0.5Ca magnesium alloy. Materials 2018, 11, 2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.-H.; You, B.-S.; Dong Yim, C.; Seo, Y.-M. Texture and microstructure changes in asymmetrically hot rolled AZ31 magnesium alloy sheets. Mater. Lett. 2005, 59, 3876–3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrin, Y.; Yi, S.B.; Brokmeier, H.G.; Zuberova, Z.; Yoon, S.C.; Kim, H.S.; Hellmig, R.J. Microstructure, texture and mechanical properties of the magnesium alloy AZ31 processed by ecap. Int. J. Mater. Res. 2008, 99, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serebryany, V.N.; Ivanova, T.M.; Savyolova, T.I.; Dobatkin, S.V. Effect of texture on tensile properties of an ecap-processed MA2-1 magnesium alloy. Solid State Phenom. 2010, 160, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.B.; Zheng, M.Y.; Hu, X.S.; Wu, K.; Xu, S.W.; Kamado, S.; Kojima, Y. Influence of ecap routes on microstructure and mechanical properties of Mg–Zn–Ca alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2010, 527, 4250–4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, S.R.; Mehrotra, P.; Lillo, T.M.; Stoica, G.M.; Liaw, P.K. Texture evolution of five wrought magnesium alloys during route a equal channel angular extrusion: Experiments and simulations. Acta Mater. 2005, 53, 3135–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, S.R.; Mehrotra, P.; Lillo, T.M.; Stoica, G.M.; Liaw, P.K. Crystallographic texture evolution of three wrought magnesium alloys during equal channel angular extrusion. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2005, 408, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabirian, F.; Khan, A.S.; Gnäupel-Herlod, T. Plastic deformation behavior of a thermo-mechanically processed AZ31 magnesium alloy under a wide range of temperature and strain rate. J. Alloy. Compd. 2016, 673, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, V.M. Severe plastic deformation: Simple shear versus pure shear. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2002, 338, 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Alloy/Composition | Processing | d, μm | σ0.2, MPa | σUTS, MPa | εf, (%) | σ−1, MPa | Nfc | CR, mm/year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZX40 A/Mg–4.0Zn–0.1Ca | ECAP, 325 °C | 28 ± 13 | 71 ± 4 | 265 ± 3 | 20 ± 2 | 55 ± 3 | 1.0 × 105 | 4.4 ± 0.2 |

| ZX40 A/Mg–4.0Zn–0.1Ca | ECAP+RS | 10 ± 6 | 348 ± 5 | 381 ± 5 | 5.0 ± 0.5 | 118 ± 3 | 1.7 × 105 | 3.0 ± 0.2 |

| ZX40 B/Mg–4.0Zn–0.56Ca | ECAP, 325 °C | 9 ± 7 | 127 ± 3 | 271 ± 6 | 22 ± 2 | 70 ± 3 | 7.5 × 104 | 2.4 ± 0.5 |

| ZX20/Mg–2Zn–0.2Ca [50] | Hot extruded | - | 118 ± 6 | 211 ± 11 | 24 ± 1 | 80* | - | - |

| ZK60 [51] | MIF** 300 °C | 5 ± 4 | 235 ± 7 | 328 | 31 ± 3 | 105 ± 3 | 3–7 × 105 | 2.6 ± 0.5 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vinogradov, A.; Vasilev, E.; Kopylov, V.I.; Linderov, M.; Brilevesky, A.; Merson, D. High Performance Fine-Grained Biodegradable Mg-Zn-Ca Alloys Processed by Severe Plastic Deformation. Metals 2019, 9, 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/met9020186

Vinogradov A, Vasilev E, Kopylov VI, Linderov M, Brilevesky A, Merson D. High Performance Fine-Grained Biodegradable Mg-Zn-Ca Alloys Processed by Severe Plastic Deformation. Metals. 2019; 9(2):186. https://doi.org/10.3390/met9020186

Chicago/Turabian StyleVinogradov, Alexei, Evgeni Vasilev, Vladimir I. Kopylov, Mikhail Linderov, Alexander Brilevesky, and Dmitry Merson. 2019. "High Performance Fine-Grained Biodegradable Mg-Zn-Ca Alloys Processed by Severe Plastic Deformation" Metals 9, no. 2: 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/met9020186