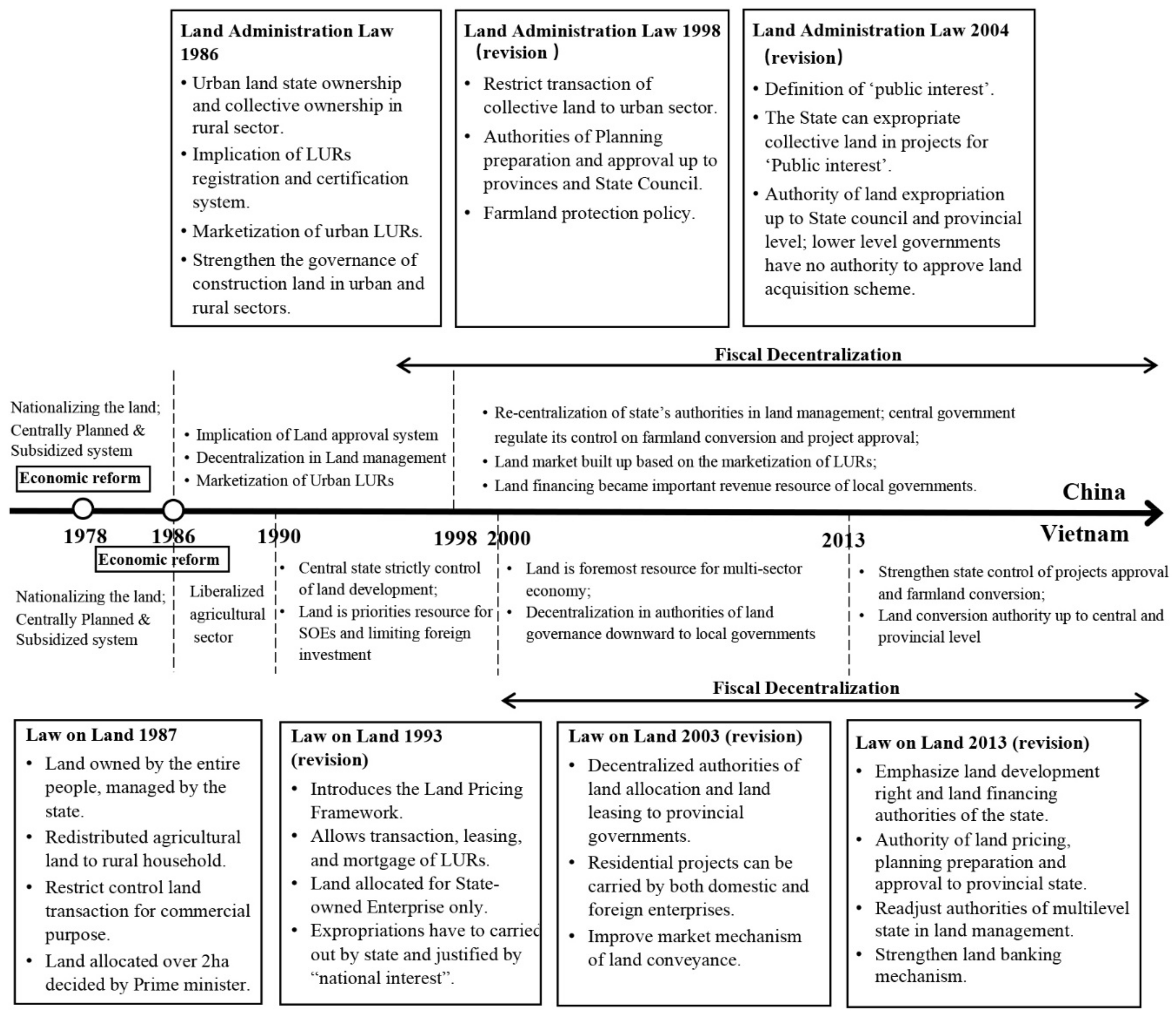

3.1. Ambiguous Boundary of State Intervention in Land Acquisition

All member nations of the old socialist system devised land legislation based on the principles of state ownership or the people’s ownership of all land, which allows the state to represent the “entire people” to expropriate land for public projects. In Vietnam, the current land conversion mechanism includes two major modes: compulsory land acquisition, which is based on the administrative decision of state bodies, and voluntary land conversion, which is based on the transaction of LURs between original land users and investors through negotiation. Compulsory land acquisition, which involves direct intervention by the state, has a profound impact on the livelihood of displaced land users. Therefore, there is an urgent need to clearly demarcate the boundary of the state’s power with respect to the purpose and extension of compulsory land acquisition. However, the 2013 Land Law in Vietnam assigned local governments the authority to acquire land for purposes of socioeconomic development, in line with “national and public interest”, which is broadly defined. Similarly, the “State-owned Land on the Housing Levy and Compensation Ordinance”, published in 2011 in China, emphasizes that the government can expropriate land and other properties for the purpose of “public interest” without the consent of the property owner.

In the name of “national and public interests” (Compulsory land acquisition in Vietnam applied to the purpose of national defense or the development of the economy/society for the national and public interest requires illegal land use (for more detail, see Law on Land 2013: article No. 61–65).), governments in C&V are granted the power to convert land from the rural sector for urban development in the pursuit of economic growth and industrialization. In recent years, both countries have experienced rapid state-led urbanization processes, and a massive amount of rural land has been converted to meet the growing demand for urban expansion and industrial development [

20,

26]. In fact, from 2001 to 2009, it has been estimated that approximately one million hectares of farmland in Vietnam was converted for urban use [

27]. In contrast, in China, widespread urban expansion caused a total loss of 3.3 million hectares of farmland during 2001 and 2013 [

28].

Although the scope of “public interest” is limited by the law, the concept of “national interest” and “public interest” in C&V does not restrict government expropriation decisions because of its ambiguity. This definition confuses economic growth and state-led urban development with the actual public interest of citizens. In this sense, the state-led construction of high-tech zones, industrial parks, and new towns (khu do thi moi) can also be considered within the scope of “public interest”. Under the current land legislation system, the authority to acquire land based on land-use planning is granted to multiple levels of government, which can prepare and approve land-use planning and become involved in land acquisition within their territory. In theory, land-use planning should represent the “public interest” in urban development; however, both countries share some common issues in contemporary land-use planning. First, such planning reflects the ideology of state intervention in the land market, and has become an important tool for implementing state-led development projects. Second, land-use planning in C&V reflects the will of the government in local development rather than market demand, and becomes the legal foundation for attracting investment. Third, the current planning systems in both countries have a serious lack of public participation in the planning preparation and approval process. Hence, land-use planning in both countries is more of a state instrument to regulate land-use development than a means to fully represent the “public interest”.

In theory, compulsory land acquisition in Vietnam is applied only to public security, welfare and foreign investment projects. Private and commercial projects funded by domestic investment are not subjected to compulsory land conversion; developers have to negotiate with the land users in LURs transactions based on the market mechanism. Nevertheless, in practice, local governments often become involved in land acquisition for many real estate projects under the name of land-use planning or new town development. Many examples can be found in Vietnam’s cities. For instance, compulsory land acquisition was applied to the large-scale development of Eco-park, a new town in Hanoi, and Thu Thiem, a new district in Ho Chi Minh City [

29,

30]. In addition, market instruments, namely “land for infrastructure” and “build–transfer”, are widely applied in many cities in Vietnam to the construction of public infrastructure. With these instruments, the state can treat land as a type of payment for the cost of building infrastructure and public facilities [

1]. After the projects are finished, developers are allocated land by the government to invest in commercial projects or commodity housing. Certainly, such land is also within the scope of compulsory acquisition for “public-interest” projects.

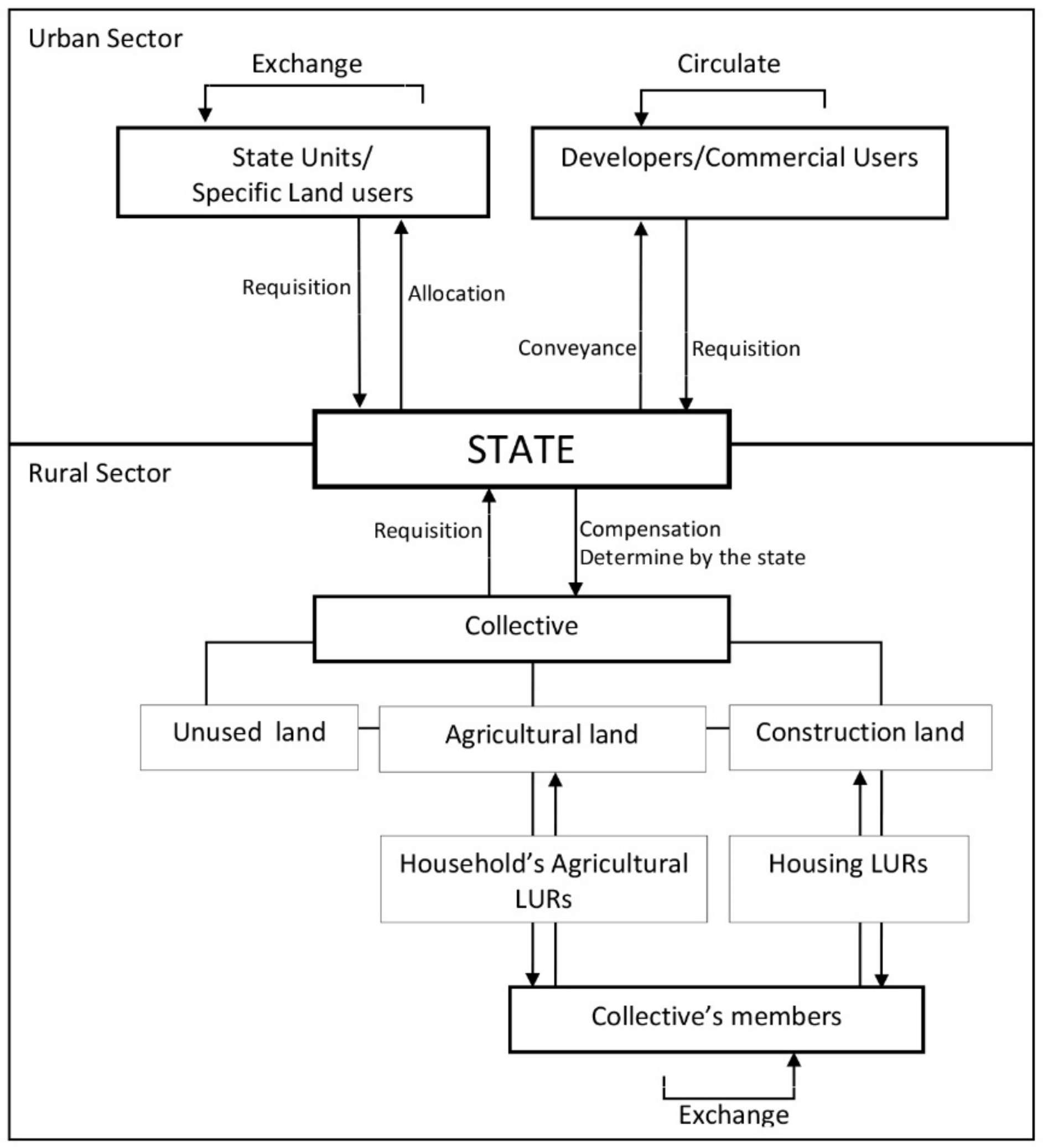

In China, no type of collective land can be directly transferred between rural land users and developers, which marks a significant difference in land conversion practices between the two countries. Because the land contract and management of collective LURs can only be internally circulated within the town and the collective’s members (including arable land, collectively owned construction land, and homestead land) (The economic reform in China, known as “gaige kaifang”, started in 1978. In Vietnam, this process, known as “Doi Moi”, began in 1986. In both countries, it was an economic and political reform initiated with the introduction of policy change from a planned economy towards a “socialist-oriented market economy”.), the only legal way to transfer land from the rural sector to the urban land market is through the land conversion process of the state, either for “public-interest” purposes or for commercial purposes. This is emphasized in article No. 43 of China’s Land Administration Law: “any unit or individual that needs to use land for construction must apply for the use of state-owned land in accordance with the law”. This regulation strengthens the ‘monopoly power’ of the government in rural land expropriation, and makes the state the only land supplier on the primary land market in China.

To strengthen the land supply capacity of the state, the land banking mechanism was introduced in the late 1990s, and rapidly became a major land expropriation model in China, while in Vietnam, this mechanism was introduced for the first time in 2003. Land banking strengthens the ability of governments to collect land for future urban development by purchasing sites and requiring land parcels based on land-use planning and the local government’s economic development scheme. The separate land parcels are collected from land banking agencies, which carry out demolition, land levelling, and the construction of public facilities to meet the land transfer standards. Certainly, this mechanism can improve the municipal government’s ability to regulate and control the land market, improve the efficiency of land development and increase local land revenue. However, in addition to these positive effects, under the current land regime, land banking also raises concerns about the dominant power of the state in land governance.

In Vietnam, the 2013 Law on Land allows provincial-level governments to establish “land banking and trading” agencies that are responsible for land conversion according to land-use planning. This mechanism has raised concerns about the dominant power of provincial-level governments in land development, especially since agricultural land in Vietnam can only be converted for urban use by the state (Compulsory land acquisition in Vietnam applied to the purpose of national defense or the development of the economy/society for the national and public interest requires illegal land use (for more detail, see Law on Land 2013: article No. 61–65).). In the case of China, as analyzed above, provincial governments have supreme authority in rural–urban land conversion. Similar to Vietnam, the implementation of the land banking system consolidated authority in rural–urban land conversion to create “monopolization” among Chinese local governments, where local governments are granted a series of responsibilities, including land-use planning preparation, compulsory land acquisition for development and land pricing. Hence, the governments in C&V play the role of both “the player and the referee” in the land development process, and their dominant power is legitimized by the law. In both countries, the boundary between state intervention and the market mechanism in rural land acquisition policies has not been clearly defined, which raises concerns regarding inequality in land development.

3.2. Dual Track of Land Pricing in Land Compensation

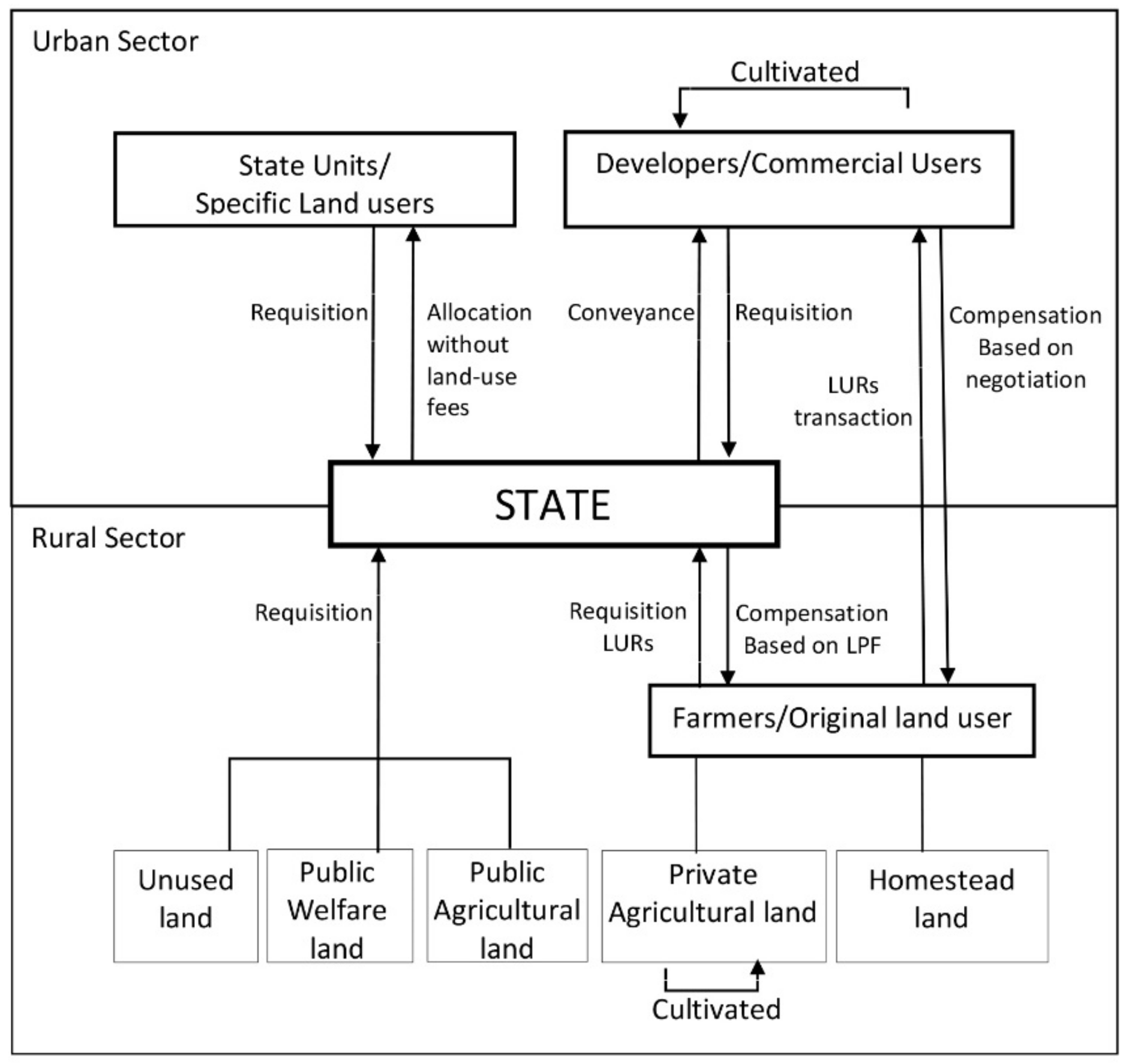

In Vietnam, land pricing is a powerful tool used by the state to regulate the land market. Since the early 1990s, the land-price framework (hereafter, LPF) has been used by the state as an instrument for all land-related valuations in the country, including establishing the compensation plan, allocating and leasing land, and calculating tax revenue [

31]. Truong and Perera (2011) argued that this land pricing mechanism was intentionally designed by the state to attract more investment and control the accessibility of land to developers [

32]. In 2003, the Law on Land officially granted provincial governments the authority to issue the LPF. The official land price in each province is annually adjusted to match the changing land value on the market. However, some recent studies have found that the official land price has failed to reflect the prevailing value of land. Indeed, the state-proposed rates for land appear to be 30–70% lower than the estimated market value [

27,

32]. This dual track of land pricing in Vietnam has been shaped by the state’s fixed land price and the prevailing price on the land transaction market.

In Vietnam, the compensation rate for compulsory land acquisition by the state is determined based on the LPF. Under this land pricing system, the cost of land compensation is minimized, which increases the investment profits for the parties of interest. Such profits are generated by the value gap between the dual track of land prices, which is determined by the administrative framework, and the market land price. In this way, developers capture substantial benefits from land value increases through development, while the profits flow to the state’s budget in the form of rental fees and related land taxes. Scholars in Vietnam have widely observed unequal benefit sharing between stakeholders in rural land conversion, where land-losing farmers tend to benefit the least [

33,

34]. Therefore, the inequality of interests between the multiple stakeholders in land conversion has created conflicts in the stage of land compensation, which has led to delays in construction and harmed the interests of investors, with effects carrying down to the people and the local economy.

In China, the dual-track land tenure system and the limitations of property rights in the rural sector have widened the gap in land prices between the urban and rural sectors. Because rural LURs can only be internally circulated within the township’s organization and the collective’s members, collective land is restricted to transfer in the secondary land market (Article 63 of the Land Administration Law 2004 stipulates as follows: no right to the use of land owned by peasant collectives may be assigned, transferred, or leased for non-agricultural construction, with the exception of enterprises that have lawfully obtained land for construction in conformity with the overall plan for land utilization but have to transfer, according to law, their land-use right because of bankruptcy or merger, or for other reasons.). These regulations strengthen the state’s control over access to collective land, and greatly weaken the property rights of rural land users and artificially keep the value of collective land lower than its market value.

As in Vietnam, current legislation on rural land compensation, which was established by the state, also purposely reduces the cost of land expropriation in China. Article No. 47 of the Land Administration Law states that “the value of compensation for cultivated land according to the original purpose of the land being expropriated and the total land compensation and resettlement subsidies shall not exceed 30 times the average annual output value of the expropriated land calculated on the basis of three years preceding such expropriation”. This law also stipulates that compensation for other types of collective land, such as construction land and homestead land, should refer to the rates of compensation and resettlement subsidies for the expropriation of cultivated land. Under these mechanisms, the collective and its members receive only a fixed price in compensation that is decided by the administrative track, which is based on the agricultural productivity of the land without considering the market value. This artificially low compensation price has failed to maintain the living standard of affected farmers [

5,

35]. Conversely, this dual track of land pricing allows the government to expropriate collective land with low compensation costs, and then gain substantial profits from land value increases achieved through land conveyance. This process supports the observation of Lin that the state uses it authority to foster the land market and incentivizes local governments to pursue land finance and local economic growth [

2].

3.3. Land Conveyance System and Rural–Urban Land Transactions

The unique land ownership system in China has created a dual land market system between the urban and rural sectors. As analyzed above, the only legal way to transfer collective land to the urban land market is through conversion by the state (

Figure 2). The authority over land-use planning and the establishment of the land banking mechanism have created a monopoly position for the state in land supply for urban development. After land expropriation, the government reassigns the LURs to new land users or developers through land conveyance or the administrative allocation of land (tudi huabo) (“Tudi huabo”: The administrative land allocation method is used to grant LURs to state or nonprofit users without any fees in China.). Land conveyance is a leasehold system whereby land parcels are conveyed to developers for a fixed term and fixed function through tender, auction, quotation, and negotiation modes (Land Administration Law 2004). This land leasehold system is based on the principles of market operation, in which developers must compete in land prices for state land allocation. The current land legislation in China combines the administrative power of the state with new market instruments, allowing the government to monopolize the land supply and maximize its income through the land conveyance system [

2,

5].

As in China, the land leasehold system in Vietnam includes a land conveyance method (auction, bidding, and negotiation modes) and an administrative land allocation method (allocate land without leasing fee) (Article 33 of the Law on Land 2013 in Vietnam stipulates that the state can allocate land to specific users without the collection of land-use fees.), which are applied only to specific projects. Land leasing through bidding and auction is based on market principles and requires a publicized and transparent assessment process, which tends to reduce the risk of corruption and help maximize the state’s income from leasing land. By contrast, negotiation in land leasing between the government and investors can lead to mass corruption, because it grants the government the right to select investors through personal contacts and bribes, rather than based on quality and affordability [

27]. However, current land legislation in Vietnam creates ambiguity, and there are internal conflicts in the regulations related to land conveyance. For instance, the 2013 Law on Land allowed negotiated conveyances to be applied only to public amenities, affordable housing projects, and in some specific circumstances (article No. 118). Nonetheless, article No. 110 in the same law allows local governments to apply negotiated conveyances to some projects “for production and business purposes in sectors or geographical areas that are given investment preferences”, except for investment projects in commodity housing. This ambiguous regulation allows local governments to appeal to developers through “under-the-table” land transactions, and to use land as an important resource to attract investment to their jurisdiction, especially for industrial and economic development. This type of ambiguous regulation can also be found in China, where local governments continuously allow land leasing to industries through negotiation. Wu (1999) argued that the negotiation of land allocation grants local governments the authority to manipulate land prices to appeal to developers [

36]. In contrast, Jiang Xu argued that this could be understood as a state strategy to sustain the competitiveness of China’s manufactured products in the global market [

9].

The major distinction in land transaction policies between C&V concerns the right to transfer land between land users and investors from the rural to urban land market (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3). In Vietnam, agricultural LURs can only be internally circulated within farmer households and agricultural organizations (Article 190 of Law on Land 2013 stipulates as follows: agricultural LURs in Vietnam can be transferred/inherited/granted only between farming households/individuals in one commune/township.). However, the LURs of homestead land can be legally transferred between land users and developers from rural to urban sectors under the mechanism of negotiation. In comparison with that in China, this transaction mechanism for homestead land in Vietnam has proved to be advantageous in some respects. First, this mechanism prevents state monopoly in rural–urban land supply. Second, the transaction mechanism ensures the rights of participation and negotiation for land users in the land development process; hence, it efficiently protects the interest of the affected people in land development. Third, the legitimization of transaction rights regarding homestead land has positively improved the development of the formal land market in Vietnam and reduced illegal land transactions between rural and urban land users. However, current land legislation still restricts transactions shifting agricultural land to the urban sector. In this sense, the government in Vietnam maintains its monopoly position in agricultural land conversion. In fact, a large amount of agricultural land has been converted to non-agricultural use by the administrative decisions of multiple levels of government in recent years [

11].