Synthesis of High Performance Cyclic Olefin Polymers (COPs) with Ester Group via Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization

Abstract

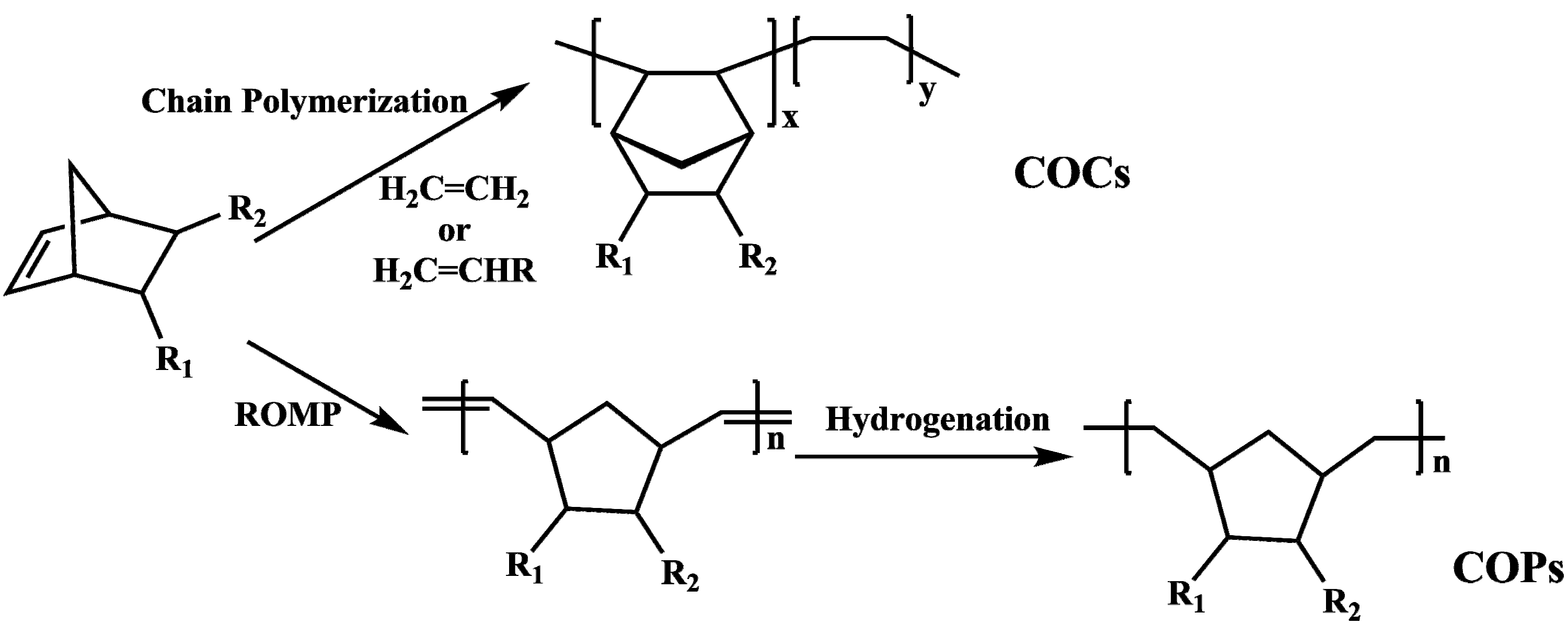

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. General

2.1.1. Procedure and Materials

2.1.2. Characterization

2.2. Ring-Opening Metathesis (Co)polymerization and Hydrogenation Procedure

2.3. Preparation of Film

3. Results and Discussion

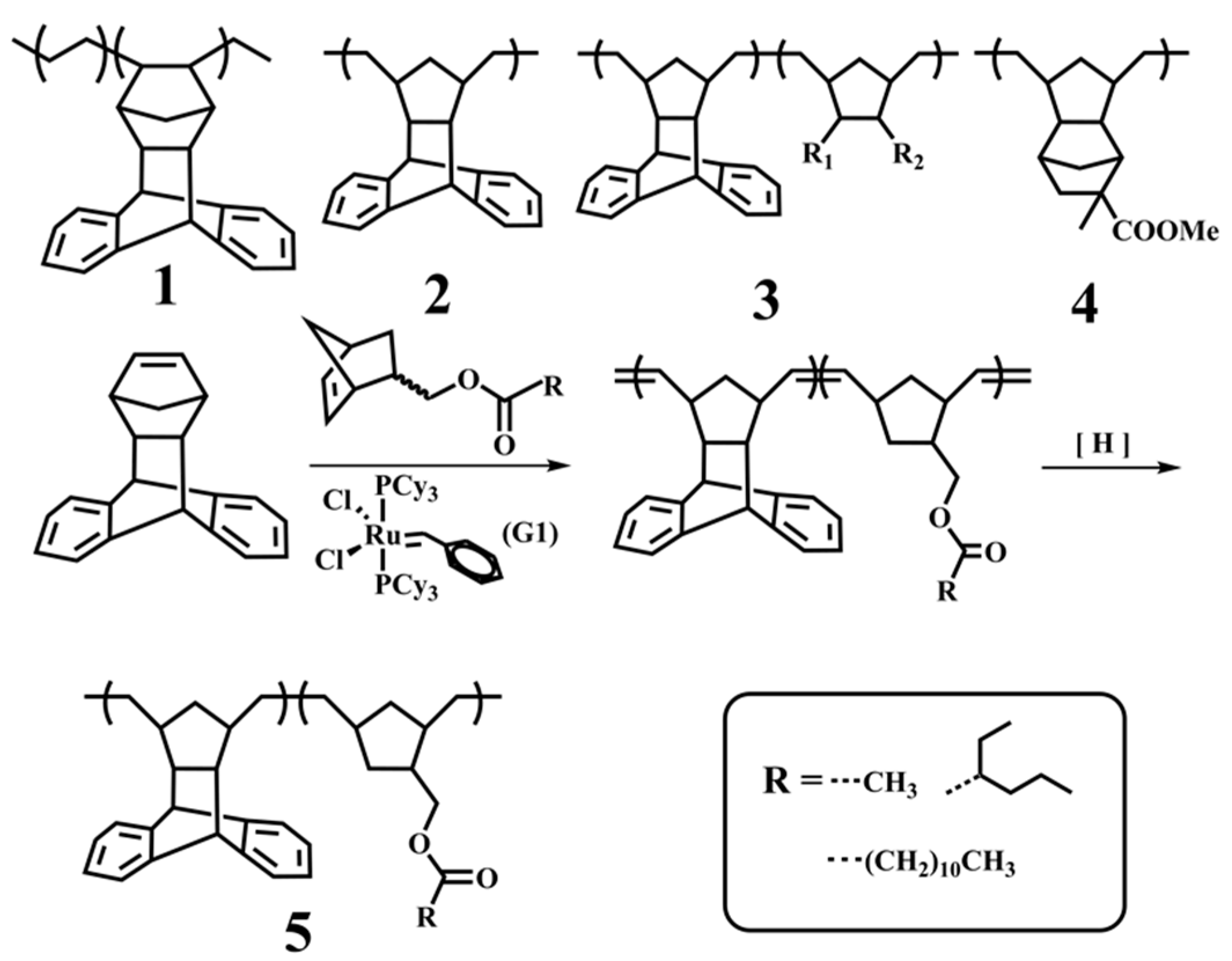

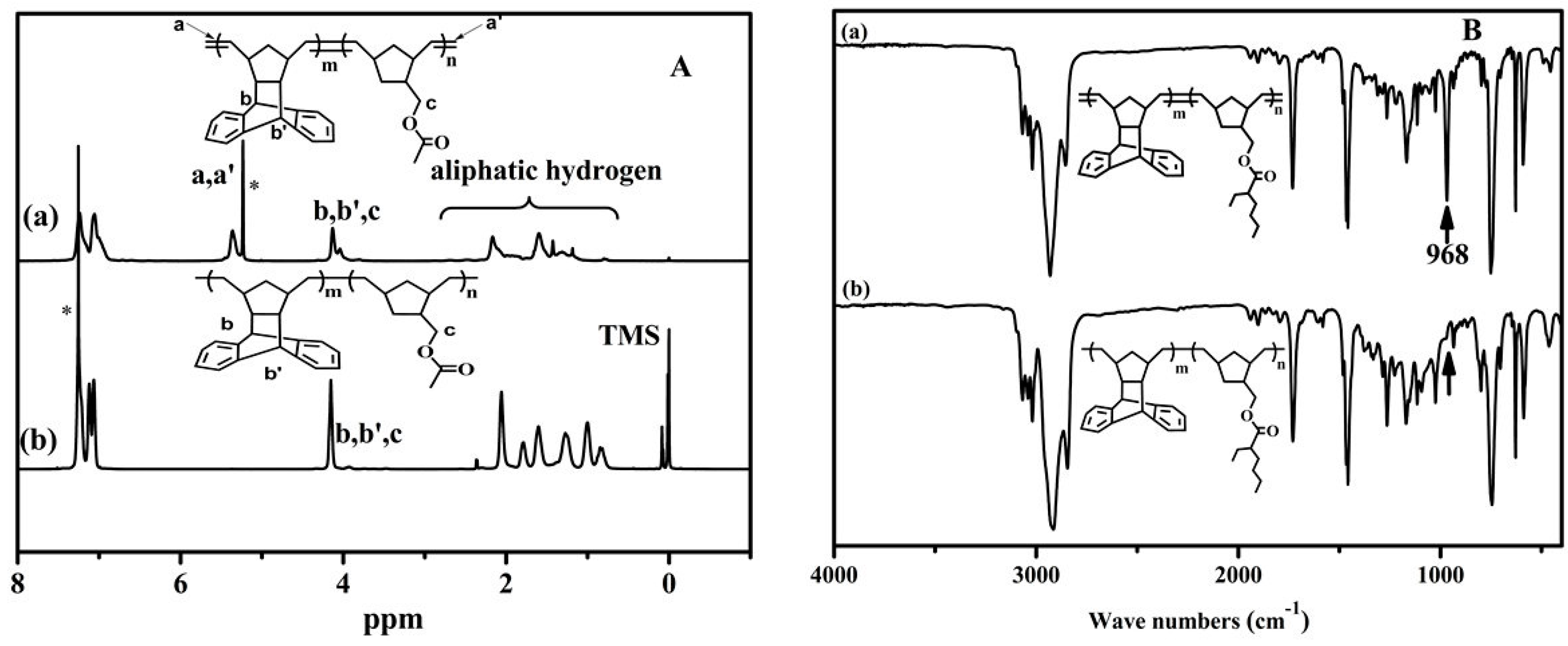

3.1. HBM/Comonomer Copolymerization

| Run | [HBM]:[M] b | HBM (mol%) c | Before Hydrogenation d | After Hydrogenation d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn (104) | PDI | Mn (104) | PDI | |||

| 1 | HBM/– | 100 | 9.2 | 1.29 | 9.1 | 1.29 |

| 2 | HBM/NMA (90:10) | 90.8 | 5.3 | 1.53 | 5.7 | 1.48 |

| 3 | HBM/NMA (80:20) | 81.8 | 8.0 | 1.54 | 9.8 | 1.45 |

| 4 | HBM/NMA (70:30) | 72.5 | 4.3 | 1.60 | 5.0 | 1.56 |

| 5 | HBM/NMA (60:40) | 62.5 | 11.1 | 1.24 | 9.7 | 1.29 |

| 6 | HBM/NMA (40:60) | 41.3 | 11.2 | 1.31 | 10.8 | 1.31 |

| 7 | –/NMA | 0 | 6.9 | 1.52 | 7.3 | 1.41 |

| 8 | HBM/NME (95:5) | 96.3 | 6.3 | 1.46 | 6.6 | 1.41 |

| 9 | HBM/NME (90:10) | 90 | 10.1 | 1.29 | 10.3 | 1.26 |

| 10 | HBM/NME (85:15) | 86.5 | 9.6 | 1.32 | 9.7 | 1.28 |

| 11 | HBM/NME (80:20) | 80.5 | 11.1 | 1.24 | 9.7 | 1.29 |

| 12 | –/NME | 0 | 11.2 | 1.31 | 10.8 | 1.31 |

| 13 | HBM/NMD (95:5) | 94.8 | 6.9 | 1.40 | 9.9 | 1.39 |

| 14 | HBM/NMD (90:10) | 89.5 | 10.2 | 1.36 | 10.7 | 1.31 |

| 15 | HBM/NMD (85:15) | 85.3 | 6.0 | 1.42 | 8.8 | 1.42 |

| 16 | HBM/NMD (80:20) | 78 | 9.8 | 1.32 | 9.8 | 1.31 |

| 17 | –/NMD | 0 | 14.6 | 1.29 | 13.4 | 1.32 |

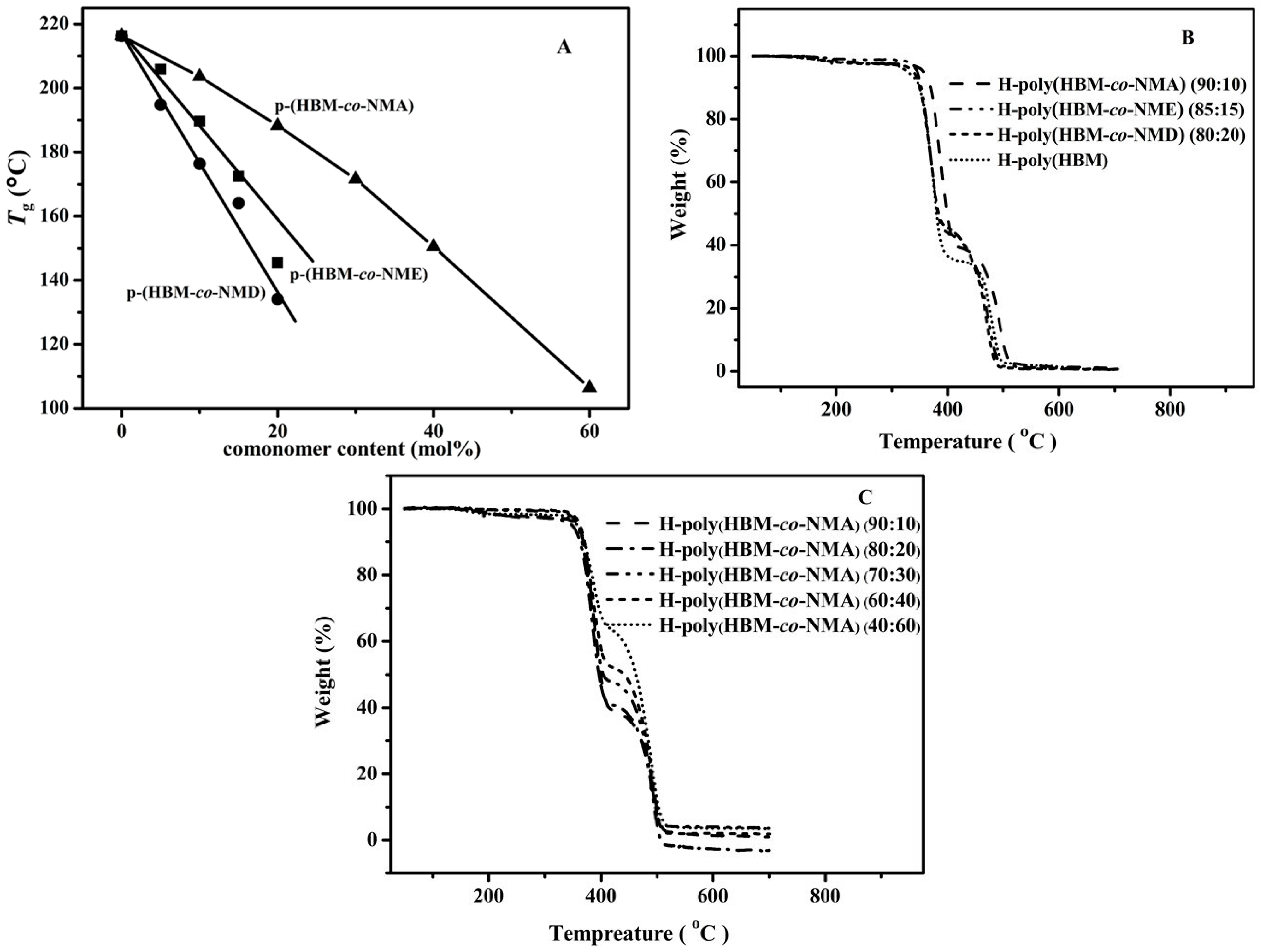

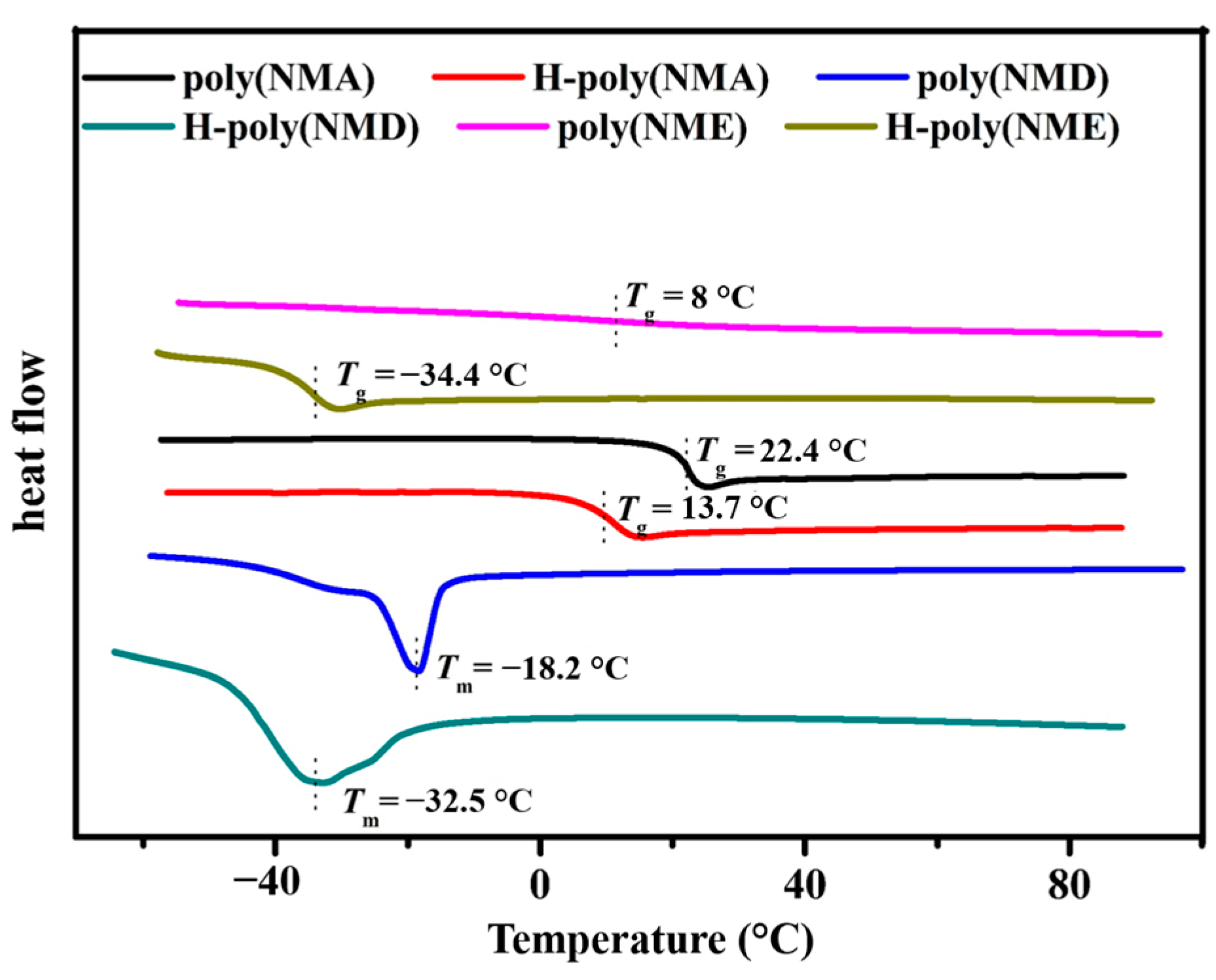

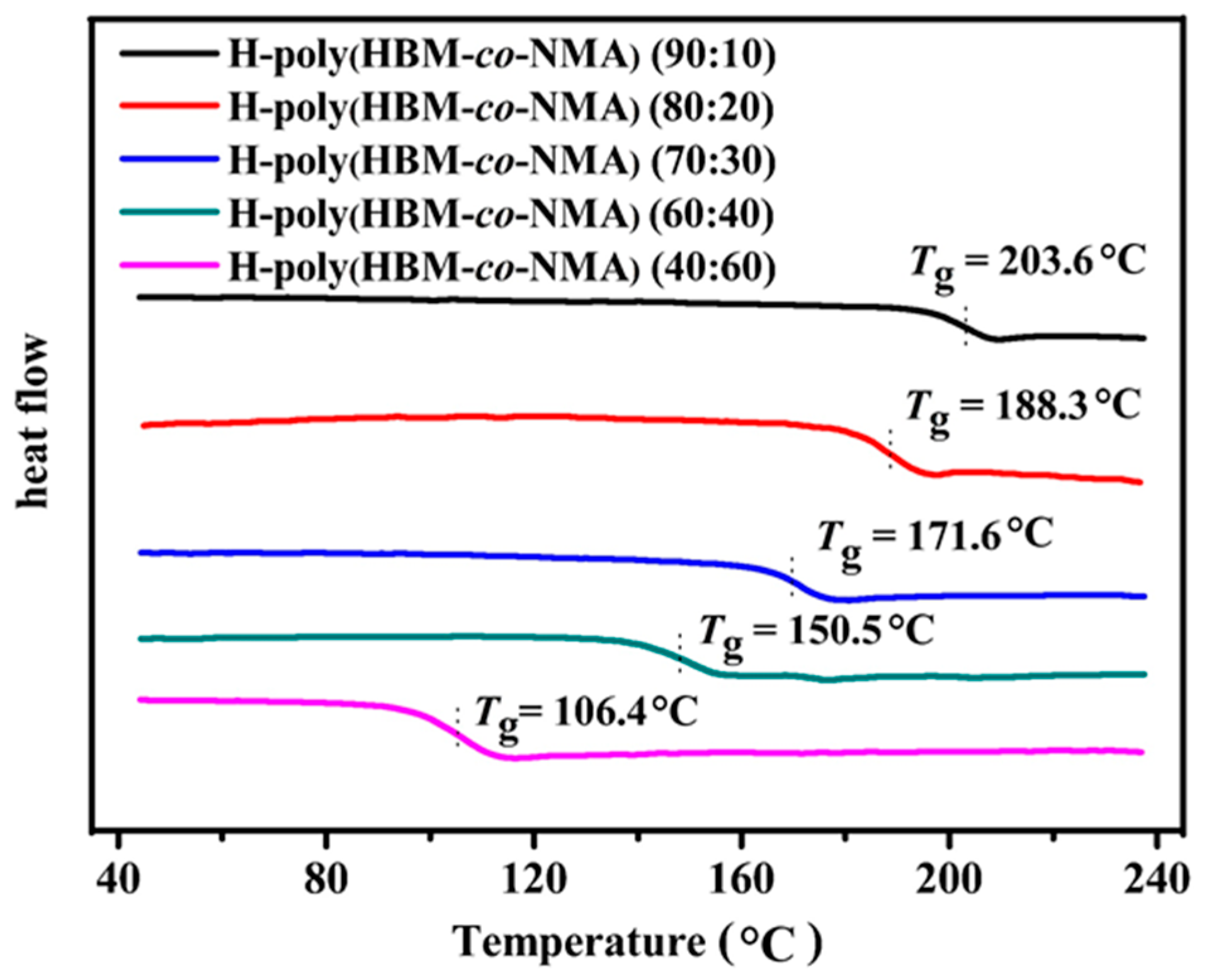

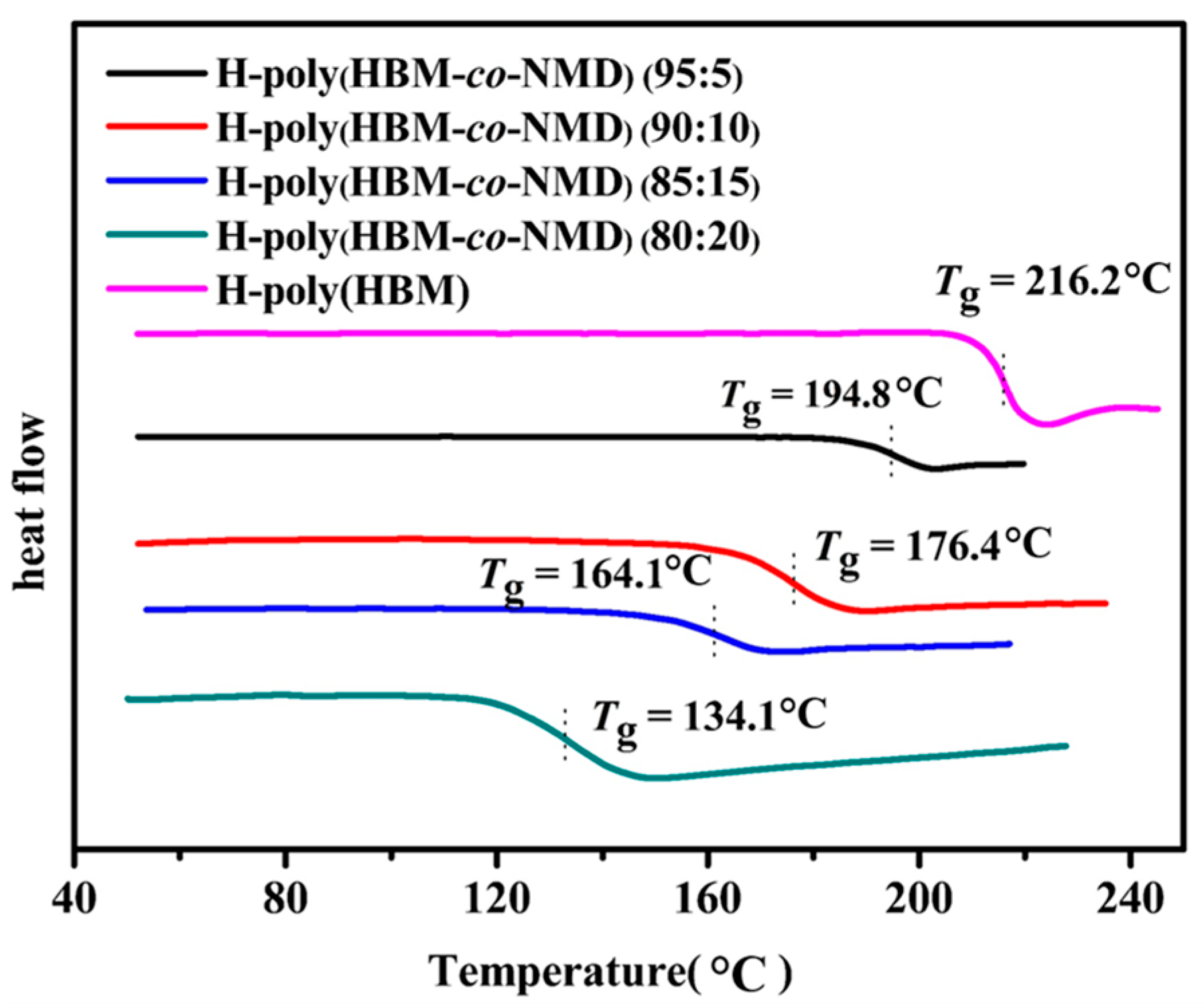

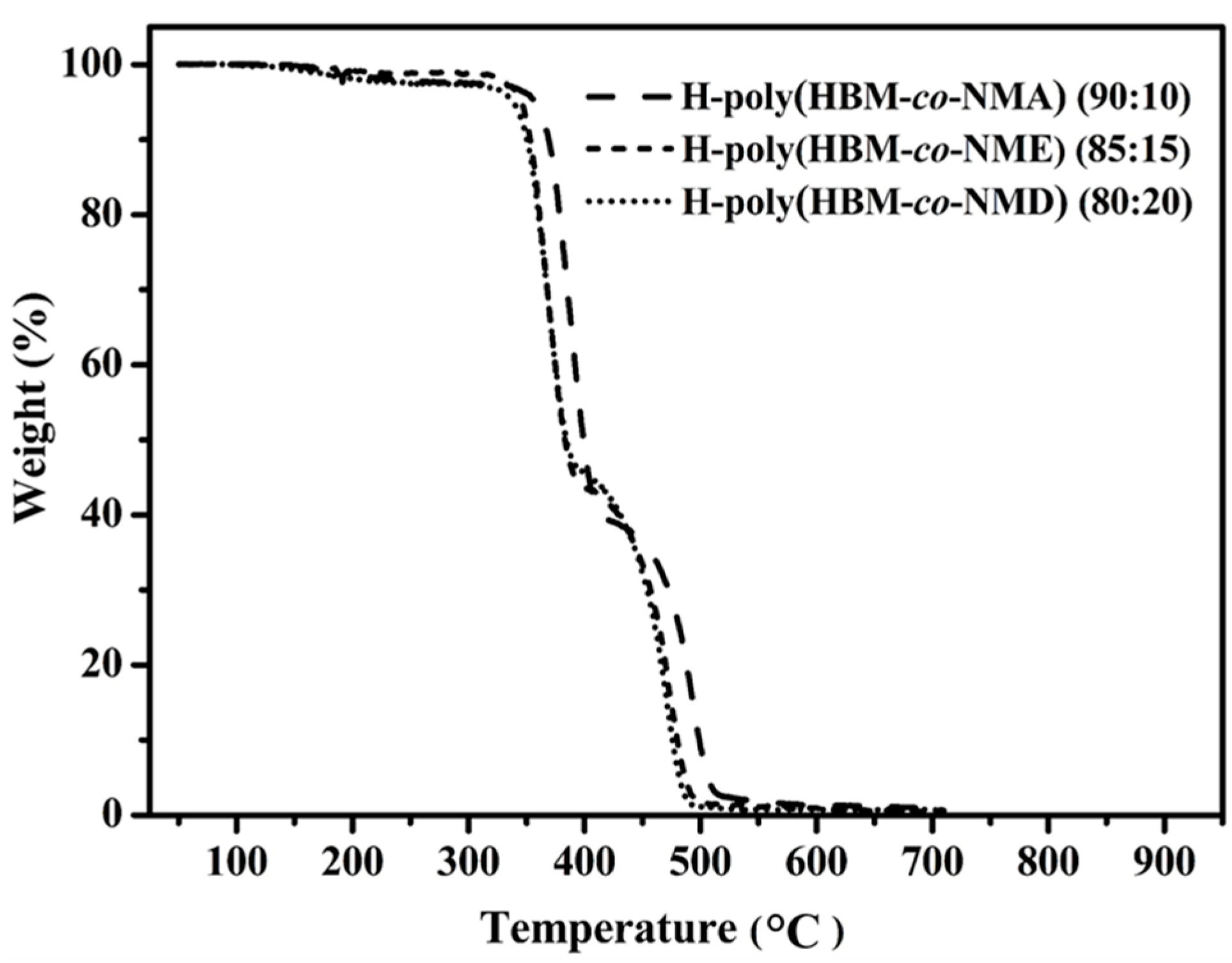

3.2. Thermal Properties of COPs

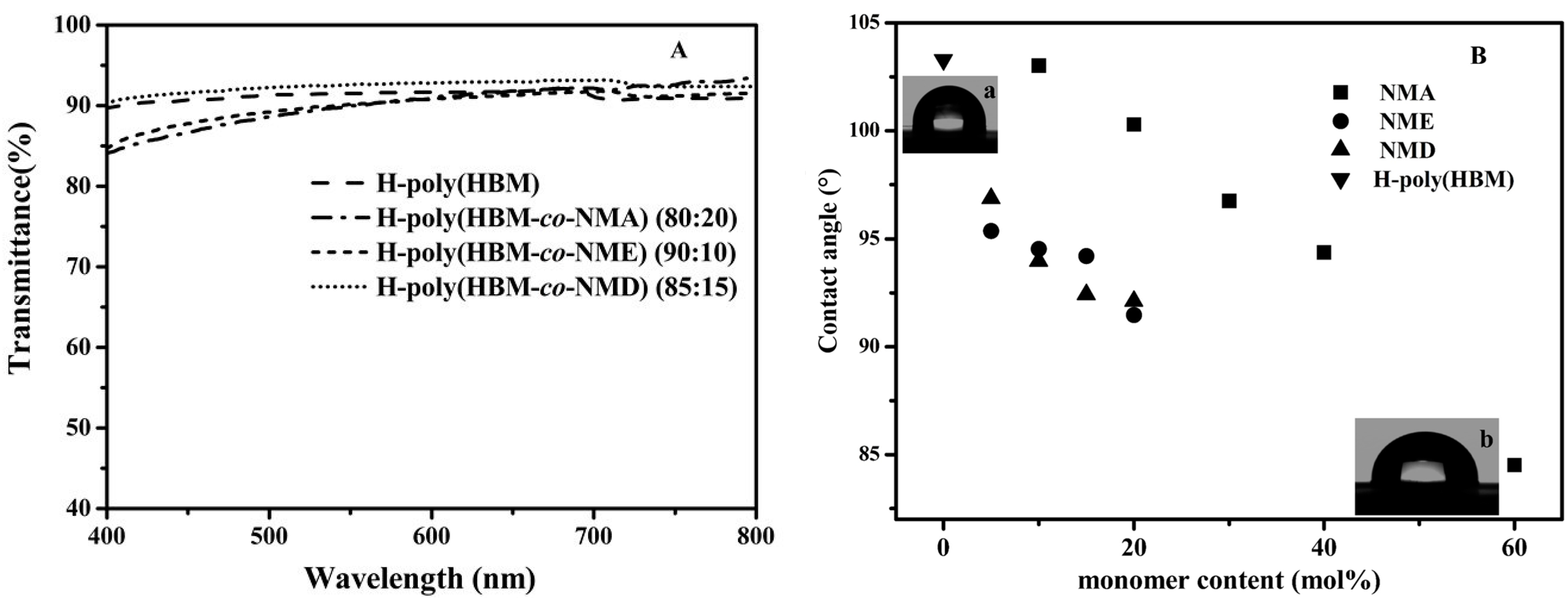

3.3. Transparency of Cyclic Olefin Copolymer

3.4. Hydrophilicity of Cyclic Olefin Copolymer

3.5. Mechanical Properties of Cyclic Olefin Copolymer

| Entry | [HBM]:[M] b | HBM mol% | σ (MPa) b | E (MPa) c | εb (%) d | Tg (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | –/HBM | 100 | 28.8 | 1,910 | 1.9 | 216.3 |

| 2 | HBM/NMA (90:10) | 90.8 | 24.4 | 1,193 | 2.8 | 203.6 |

| 3 | HBM/NMA (80:20) | 81.8 | 23.6 | 1,140 | 3.7 | 188.3 |

| 4 | HBM/NMA (70:30) | 72.5 | 23.4 | 1,102 | 4.5 | 171.6 |

| 5 | HBM/NMA (60:40) | 62.5 | 21.7 | 1,042 | 6.9 | 150.5 |

| 6 | HBM/NMA (40:60) | 41.3 | 17.7 | 1,190 | 9.7 | 106.4 |

| 7 | HBM/NME (95:5) | 96.5 | 22.4 | 1,580 | 1.7 | 205.9 |

| 8 | HBM/NME (90:10) | 90 | 22.0 | 1,350 | 1.8 | 189.7 |

| 9 | HBM/NME (85:15) | 86.5 | 20.4 | 1,320 | 2 | 172.5 |

| 10 | HBM/NME (80:20) | 80.5 | 18.8 | 1,170 | 2.8 | 145.5 |

| 11 | HBM/NMD (95:5) | 94.8 | 30.8 | 1,630 | 2.1 | 194.8 |

| 12 | HBM/NMD (90:10) | 89.5 | 28.5 | 1,557 | 2.8 | 176.4 |

| 13 | HBM/NMD (85:15) | 85.3 | 25.7 | 1,258 | 2.9 | 164.1 |

| 14 | HBM/NMD (80:20) | 78 | 19.2 | 1,077 | 3.2 | 134.1 |

4. Conclusions

Appendix

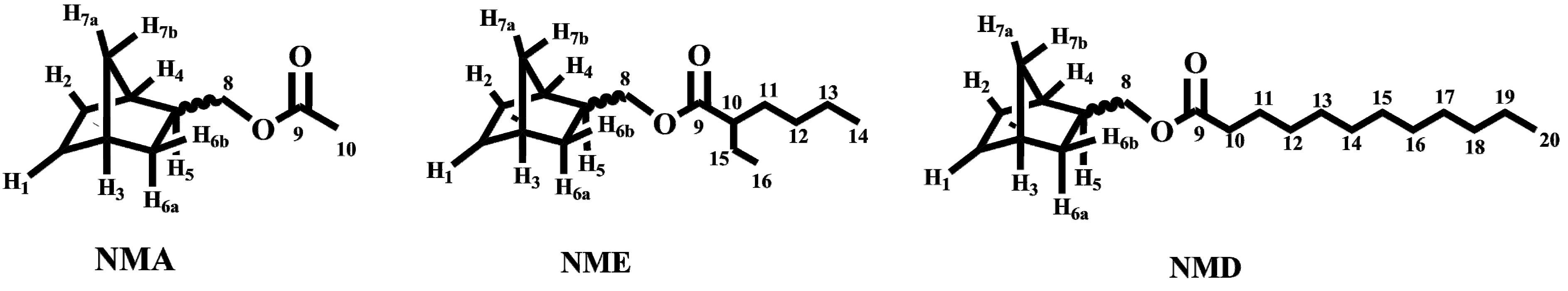

A1. Synthesis of 5-Norbornene-2-yl Methyl acetate (NMA)

A2. Synthesis of 5-Norbornene-2-yl Methyl 2-Ethylhexanoate (NME)

A3. Synthesis of 5-Norbornene-2-yl Methyldodecanoate (NMD)

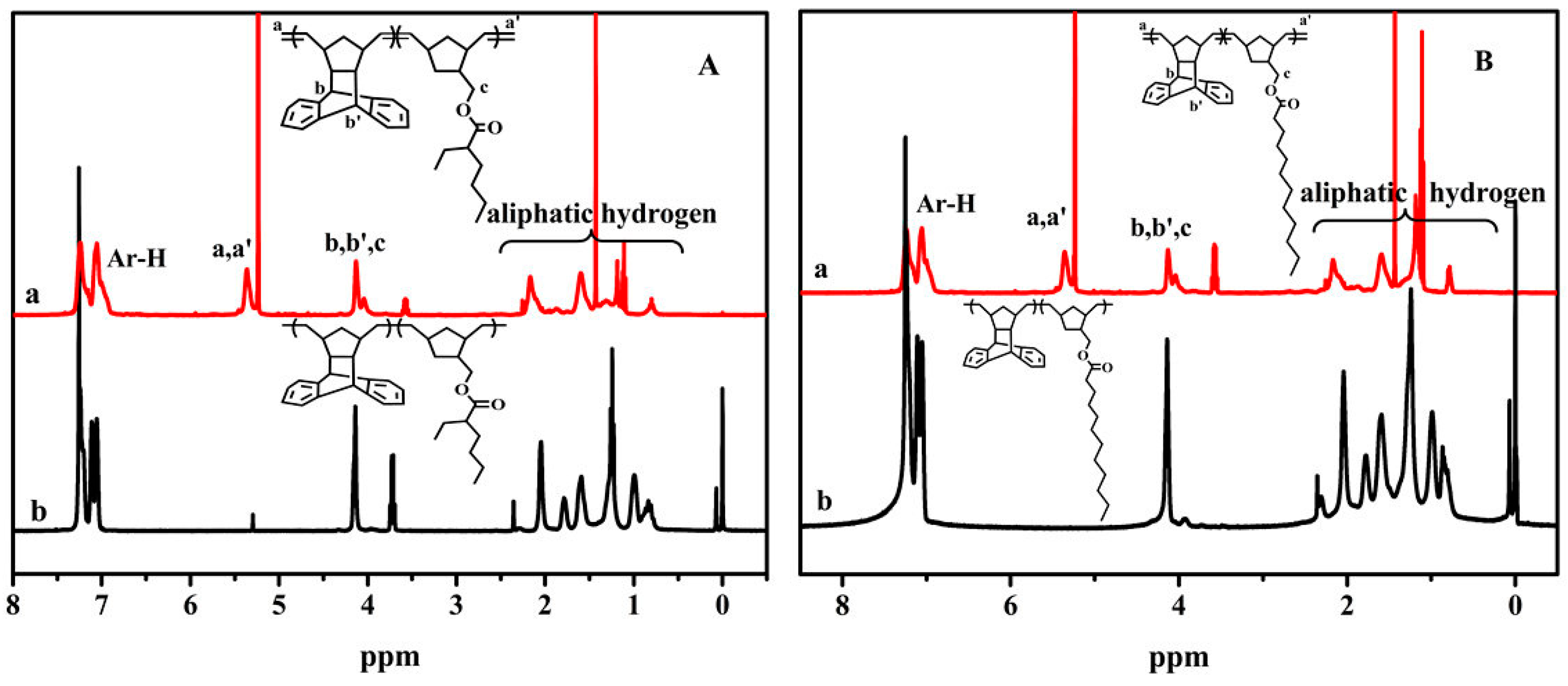

A4. The 1H NMR Spectra for the Copolymers

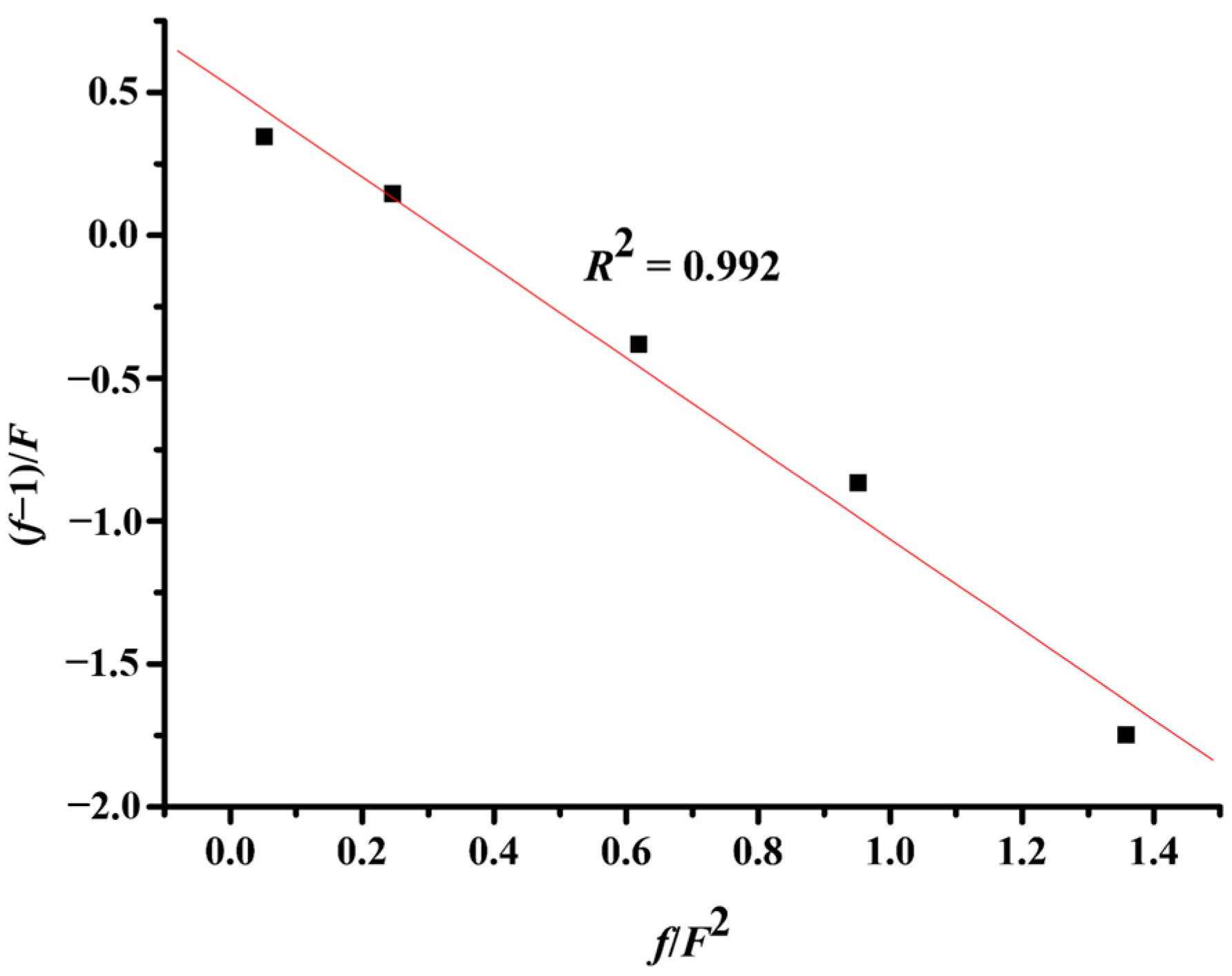

A5. Reactivity Ratios of Copolymerization

| Entry a | MNMA | MHBM | mNMA | mHBM | f b | F c | f/F2 | (f−1)/F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.285 | 0.715 | 0.399 | 0.667 | 0.897 | −0.901 |

| 2 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.483 | 0.518 | 0.932 | 1.5 | 0.414 | −0.045 |

| 3 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.563 | 0.438 | 1.286 | 2.333 | 0.236 | 0.123 |

| 4 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.848 | 0.153 | 5.557 | 9 | 0.069 | 0.506 |

| Entry a | MNME | MHBM | mNME | mHBM | f b | F c | f/F2 | (f−1)/F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.300 | 0.700 | 0.200 | 0.800 | 0.250 | 0.429 | 1.358 | –1.748 |

| 2 | 0.400 | 0.600 | 0.298 | 0.703 | 0.423 | 0.667 | 0.951 | –0.865 |

| 3 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.383 | 0.618 | 0.619 | 1.000 | 0.619 | –0.381 |

| 4 | 0.700 | 0.300 | 0.573 | 0.428 | 1.339 | 2.333 | 0.246 | 0.145 |

| 5 | 0.900 | 0.100 | 0.805 | 0.195 | 4.128 | 9.000 | 0.051 | 0.346 |

| Entry a | MNME | MHBM | mNME | mHBM | f b | F c | f/F2 | (f−1)/F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.400 | 0.600 | 0.320 | 0.680 | 0.471 | 0.667 | 1.059 | –0.794 |

| 2 | 0.500 | 0.500 | 0.427 | 0.573 | 0.747 | 1.000 | 0.747 | –0.253 |

| 3 | 0.700 | 0.300 | 0.623 | 0.377 | 1.649 | 2.333 | 0.303 | 0.278 |

| 4 | 0.900 | 0.100 | 0.863 | 0.137 | 6.273 | 9.000 | 0.077 | 0.586 |

A6. Thermal Properties of COPs

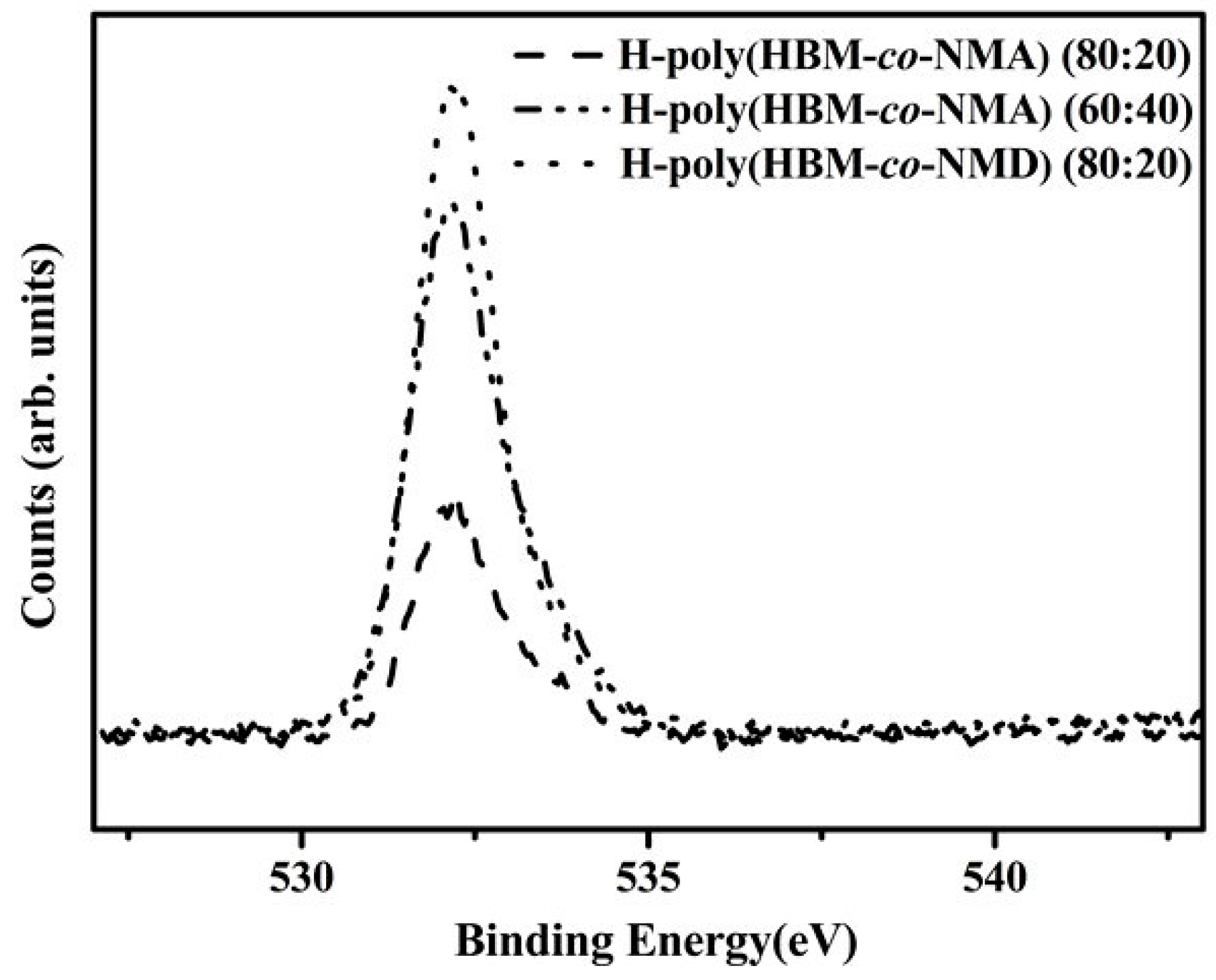

A7. X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) Test

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khanarian, G. Optical properties of cyclic olefin copolymers. Opt. Eng. 2001, 40, 1024–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mol, J.C. Industrial applications of olefin metathesis. J. Mol. Catal. A 2004, 213, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, P.; Ohlsson, P.; Ordeig, O.; Kutter, J. Cyclic olefin polymers: Emerging materials for lab-on-a-chip applications. Microfluid. Nanofluid. 2010, 9, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.Y.; Park, J.Y.; Liu, C.Y.; He, J.S.; Kim, S.C. Chemical structure and physical properties of cyclic olefin copolymers (IUPAC technical report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2005, 77, 801–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, E.S.; Joung, U.G.; Lee, B.Y.; Lee, H.; Park, Y.-W.; Lee, C.H.; Shin, D.M. Syntheses of 2,5-dimethylcyclopentadienyl ansa-zirconocene complexes and their reactivity for ethylene/norbornene copolymerization. Organometallics 2004, 23, 4693–4699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Baldamus, J.; Hou, Z. Alternating ethylene–norbornene copolymerization catalyzed by cationic half-sandwich scandium complexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 962–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Hou, Z. Organometallic catalysts for copolymerization of cyclic olefins. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2008, 252, 1842–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, A.L.; Waymouth, R.M. Ethylene/norbornene copolymerizations with titanium CpA catalysts. Macromolecules 1999, 32, 2816–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, S.J.; Wu, C.J.; Yoo, J.; Kim, B.E.; Lee, B.Y. Copolymerization of 5,6-dihydro-dicyclopentadiene and ethylene. Macromolecules 2008, 41, 4055–4057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, K.; Wang, W.; Fujiki, M.; Liu, J. Notable norbornene (NBE) incorporation in ethylene-NBE copolymerization catalysed by nonbridged half-titanocenes: Better correlation between NBE incorporation and coordination energy. Chem. Commun. 2006, 2659–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruchatz, D.; Fink, G. Ethene−Norbornene Copolymerization Using homogenous metallocene and half-sandwich catalysts: Kinetics and relationships between catalyst structure and polymer structure. 2. Comparative study of different metallocene- and half-sandwich/methylaluminoxane catalysts and analysis of the copolymers by 13C nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Macromolecules 1998, 31, 4674–4680. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ruchatz, D.; Fink, G. Ethene-norbornene copolymerization using homogenous metallocene and half-sandwich catalysts: Kinetics and relationships between catalyst structure and polymer structure. 1. Kinetics of the ethene-norbornene copolymerization using the [(isopropylidene) (η5-inden-1-ylidene-η5-cyclopentadienyl)]zirconium dichloride/methylaluminoxane catalyst. Macromolecules 1998, 31, 4669–4673. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ruchatz, D.; Fink, G. Ethene-norbornene copolymerization with homogeneous metallocene and half-sandwich catalysts: Kinetics and relationships between catalyst structure and polymer structure. 4. Development of molecular weights. Macromolecules 1998, 31, 4684–4686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tritto, I.; Boggioni, L.; Ferro, D.R. Metallocene catalyzed ethene- and propene co-norbornene polymerization: Mechanisms from a detailed microstructural analysis. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2006, 250, 212–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.T.; Na, S.J.; Lim, T.S.; Lee, B.Y. Preparation of a bulky cycloolefin/ethylene copolymer and its tensile properties. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 725–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.O.; Lin, H.F.; Yang, M.C.; Lai, M.J.; Chang, C.C.; Shiao, P.L.; Chen, I.M.; Chen, J.Y. Thermal, dynamic mechanical and rheological properties of metallocene-catalyzed cycloolefin copolymers (mCOCs) with high glass transition temperature. Mater. Lett. 2007, 61, 457–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, H.T.; Shigeta, M.; Nagamune, T.; Uejima, M. Synthesis of cyclo-olefin copolymer latexes and their carbon nanotube composite nanoparticles. J. Polym. Sci. Part A 2013, 51, 4584–4591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Wu, C.J.; Kim, W.J.; Kim, J.; Lee, H.; Kim, J.D. Ring-opening metathesis polymerization of tetracyclododecene using various catalyst systems. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2010, 116, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, O.J.; Huyen Thanh, V.; Lee, S.B.; Kim, T.K.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, H. Ring-opening metathesis polymerization and hydrogenation of ethyl-substituted tetracyclododecene. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2011, 32, 2737–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, W.R.; Wu, H.Y.; Wang, K.L.; Liaw, D.J.; Lee, K.R.; Lai, J.Y. High glass transition and thermally stable polynorbornenes containing fluorescent dipyrene moieties via ring-opening metathesis polymerization. J. Polym. Sci. Part A 2011, 49, 3673–3680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okaniwa, M.; Kawashima, N.; Kaizu, M.; Mutsuga, Y. Birefringence control by hydrogen bonding on compatible polymer pair composed of hydrogenated ring-opening polymer and modified polystyrene. J. Polym. Sci. Part A 2013, 51, 3132–3143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, E.S.; Park, J.H.; Jeon, J.; Sung, J.U.; Hwang, W.S.; Lee, B.Y. Ring-opening metathesis polymerization of dicyclopentadiene and tricyclopentadiene. Macromol. Res. 2013, 21, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiotsuki, M.; Endo, T. Synthesis of hydrocarbon polymers containing bulky dibenzobicyclic moiety by ROMP and their characteristic optical properties. J. Polym. Sci. Part A 2014, 52, 1392–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyaya, V.T.; Vo, H.T.; Putra, R.D.D.; Hwang, W.S.; Ahn, B.S.; Lee, H. Preparation and characterization of cycloolefin polymer based on dicyclopentadiene (DCPD) and dimethanooctahydronaphthalene (DMON). Eur. Polym. J. 2013, 49, 2680–2688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, M. Industrialization and application development of cyclo-olefin polymer. J. Mol. Catal. A 2004, 213, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Harada, R.; Nakayama, Y.; Shiono, T. Highly active living random copolymerization of norbornene and 1-alkene with ansa-fluorenylamidodimethyltitanium derivative: Substituent effects on fluorenyl ligand. Macromolecules 2010, 43, 4527–4531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, J.F.; Scrivani, T.; Benavente, R.; Marestin, C.; Pereña, J.M. Thermal and dynamic mechanical behavior of ethylene/norbornene copolymers with medium norbornene contents. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2001, 82, 2159–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rische, T.; Waddon, A.J.; Dickinson, L.C.; MacKnight, W.J. Microstructure and morphology of cycloolefin copolymers. Macromolecules 1998, 31, 1871–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.C.; Kim, A.; Lee, B.Y. Preparation of cycloolefin copolymers of a bulky tricyclo-pentadiene. J. Polym. Sci. Part A 2011, 49, 938–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.; Yang, G.F.; Long, Y.Y.; Yu, S.; Li, Y.S. Preparation of novel cyclic olefin copolymer with high glass transition temperature. J. Polym. Sci. Part A 2013, 51, 3144–3152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, M.; Cui, L.; Liu, S.; Li, Y. Synthesis of novel cyclic olefin copolymer (COC) with high performance via effective copolymerization of ethylene with bulky cyclic olefin. Macromolecules 2012, 45, 5397–5402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.X.; Cui, J.; Long, Y.Y.; Li, Y.G.; Li, Y.S. Synthesis of cyclic olefin polymers with high glass transition temperature by ring-opening metathesis copolymerization and subsequent hydrogenation. J. Polym. Sci. Part A 2014, 52, 2654–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.X.; Cui, J.; Long, Y.Y.; Li, Y.G.; Li, Y.S. Synthesis of novel cyclic olefin polymers with excellent transparency and high glass-transition temperature via gradient copolymerization of bulky cyclic olefin and cis-cyclooctene. J. Polym. Sci. Part A 2014, 52, 3240–3249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slugovc, C.; Demel, S.; Riegler, S.; Hobisch, J.; Stelzer, F. Influence of functional groups on ring opening metathesis polymerisation and polymer properties. J. Mol. Catal. A 2004, 213, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiono, T.; Sugimoto, M.; Hasan, T.; Cai, Z. Facile synthesis of hydroxy-functionalized cycloolefin copolymer using ω-alkenylaluminium as a comonomer. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2013, 214, 2239–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Jantasee, S.; Jongsomsjit, B.; Tanaka, R.; Nakayama, Y.; Shiono, T. Copolymerization of norbornene with ω-alkenylaluminum as a precursor comonomer for introduction of carbonyl moieties. J. Polym. Sci. Part A 2013, 51, 5085–5090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, J.B.; Raines, R.T. Olefin metathesis for chemical biology. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2008, 12, 767–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leitgeb, A.; Wappel, J.; Slugovc, C. The ROMP toolbox upgraded. Polymer 2010, 51, 2927–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slugovc, C. The ring opening metathesis polymerisation toolbox. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2004, 25, 1283–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutthasupa, S.; Shiotsuki, M.; Sanda, F. Recent advances in ring-opening metathesis polymerization, and application to synthesis of functional materials. Polym. J. 2010, 42, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trnka, T.M.; Grubbs, R.H. The development of L2X2RuCHR olefin metathesis catalysts: An organometallic success story. Acc. Chem. Res. 2001, 34, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwab, P.; Grubbs, R.H.; Ziller, J.W. Synthesis and applications of RuCl2(=CHR′)(PR3)2: The influence of the alkylidene moiety on metathesis activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, P.; France, M.B.; Ziller, J.W.; Grubbs, R.H. A Series of well-defined metathesis catalysts–synthesis of [RuCl2(=CHR′)(PR3)2] and its reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1995, 34, 2039–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tidwell, P.W.; Mortimer, G.A. An improved method of calculating copolymerization reactivity ratios. J. Polym. Sci. Part A 1965, 3, 369–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, F.R.; Lewis, F.M. Copolymerization. I. A basis for comparing the behavior of monomers in copolymerization; the copolymerization of styrene and methyl methacrylate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1944, 66, 1594–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rule, J.D.; Moore, J.S. ROMP reactivity of endo- and exo-dicyclopentadiene. Macromolecules 2002, 35, 7878–7882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutthasupa, S.; Sanda, F.; Masuda, T. Ring-opening metathesis polymerization of amino acid-functionalized norbornene diamide monomers: Polymerization behavior and chiral recognition ability of the polymers. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2008, 209, 930–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutthasupa, S.; Terada, K.; Sanda, F.; Masuda, T. Ring-opening metathesis polymerization of amino acid-functionalized norbornene derivatives. J. Polym. Sci. Part A 2006, 44, 5337–5343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutthasupa, S.; Terada, K.; Sanda, F.; Masuda, T. Ring-opening metathesis polymerization of amino acid-functionalized norbornene diester monomers. Polymer 2007, 48, 3026–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Li, G.; Xu, N.; Liu, R.; Zhang, S.-M.; Wu, Z.-J. Synthesis and critical micelle concentration of a series of gemini alkylphenol polyoxyethylene nonionic surfactants. J. Surfact. Deterg. 2011, 14, 339–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, J.M.; Fernández, F.; Garcı́a-Mera, X.; Rodrı́guez-Borges, J.E. Divergent synthesis of two precursors of 3'-homo-2'-deoxy- and 2'-homo-3'-deoxy-carbocyclic nucleosides. Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 8843–8849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2015 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cui, J.; Yang, J.-X.; Li, Y.-G.; Li, Y.-S. Synthesis of High Performance Cyclic Olefin Polymers (COPs) with Ester Group via Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization. Polymers 2015, 7, 1389-1409. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym7081389

Cui J, Yang J-X, Li Y-G, Li Y-S. Synthesis of High Performance Cyclic Olefin Polymers (COPs) with Ester Group via Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization. Polymers. 2015; 7(8):1389-1409. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym7081389

Chicago/Turabian StyleCui, Jing, Ji-Xing Yang, Yan-Guo Li, and Yue-Sheng Li. 2015. "Synthesis of High Performance Cyclic Olefin Polymers (COPs) with Ester Group via Ring-Opening Metathesis Polymerization" Polymers 7, no. 8: 1389-1409. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym7081389