Vegetable Tannin as a Sustainable UV Stabilizer for Polyurethane Foams

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

2.2. Preparations of PU and TaPU Foams and UV Treatment

2.3. Physical Properties Evaluaton

2.4. Cellular Morphology and Spectroscopy

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Foaming Process

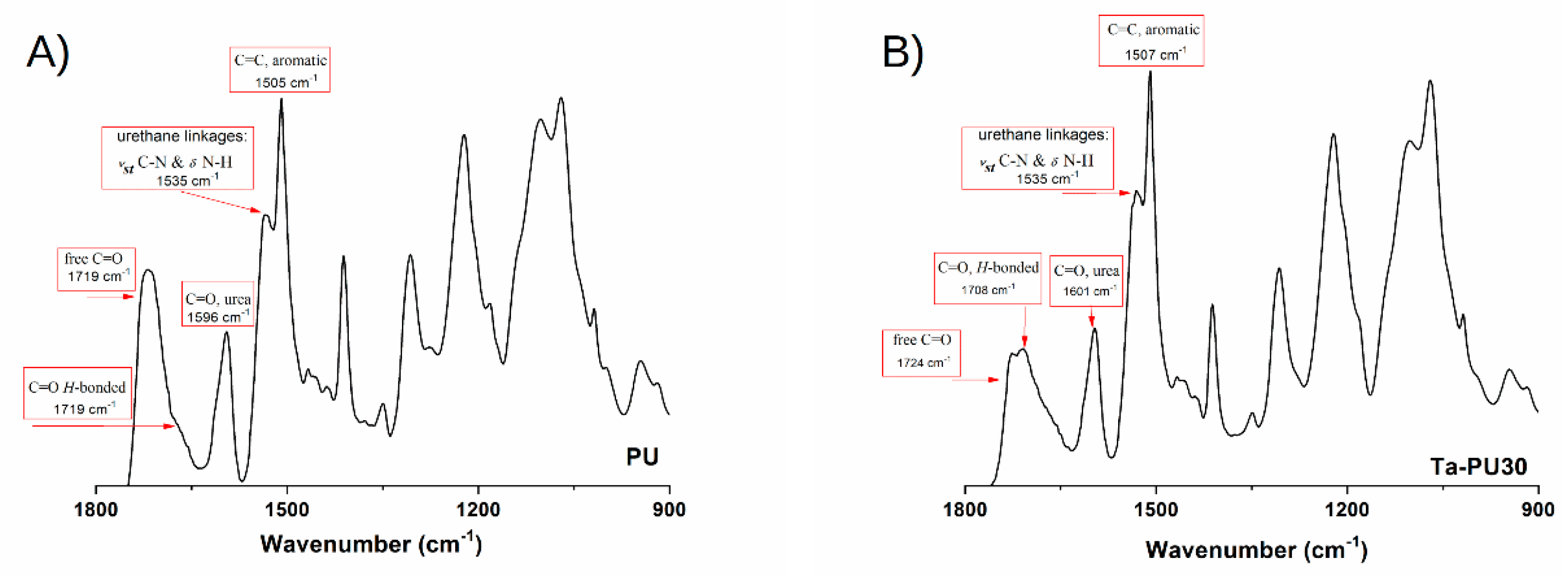

3.2. FTIR Analysis

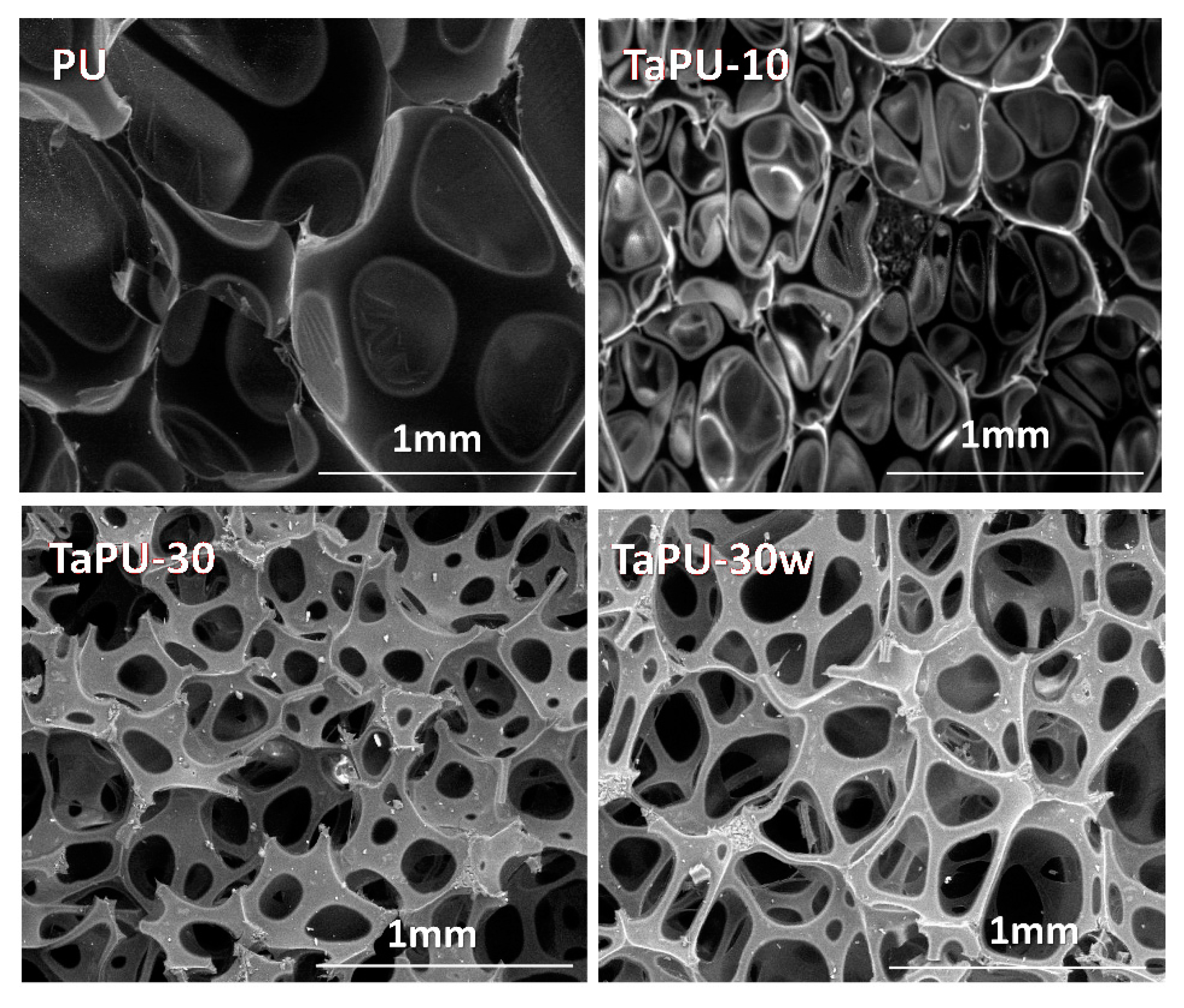

3.3. Foam Morphology

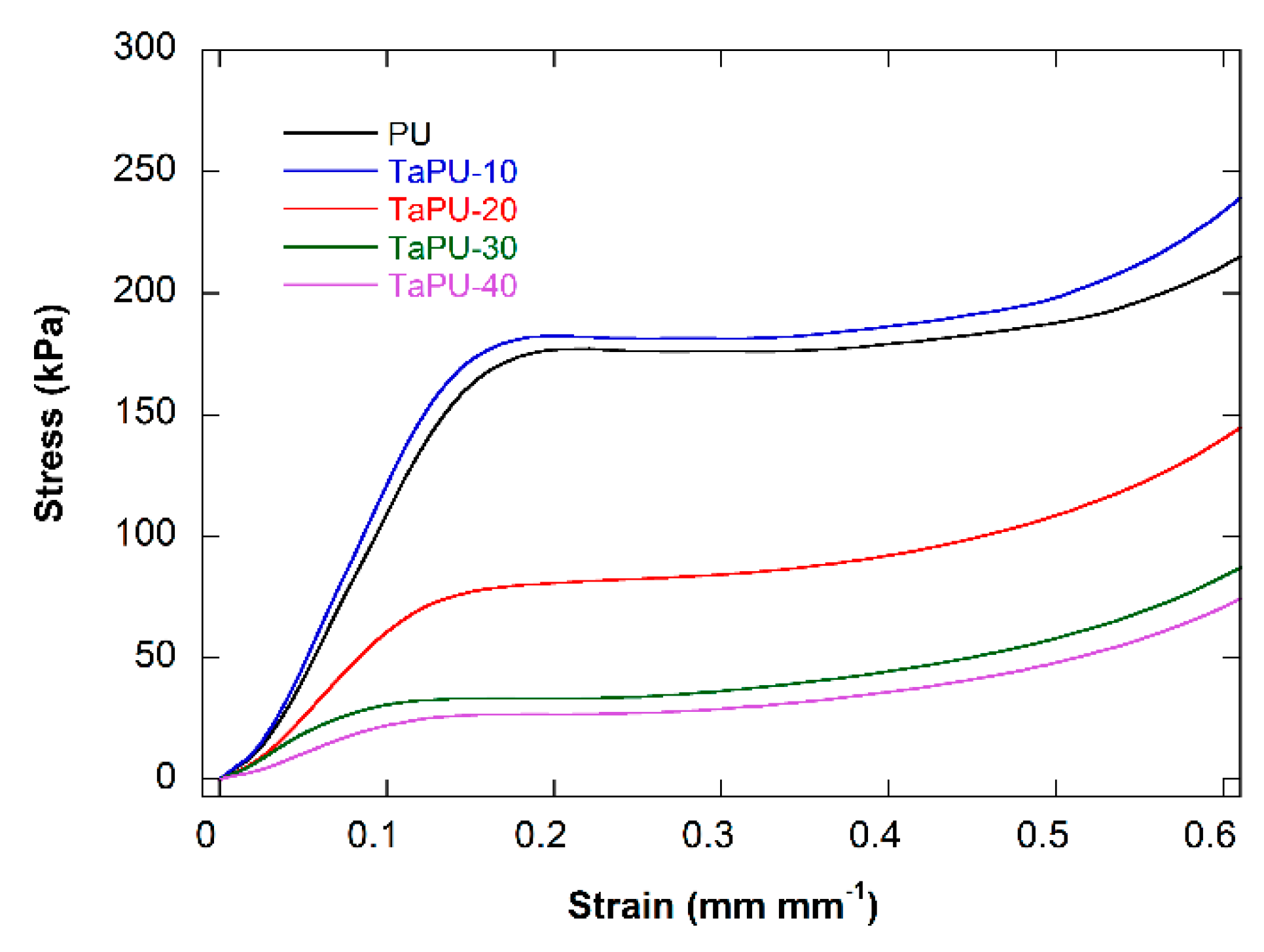

3.4. Mechanical Behaviour

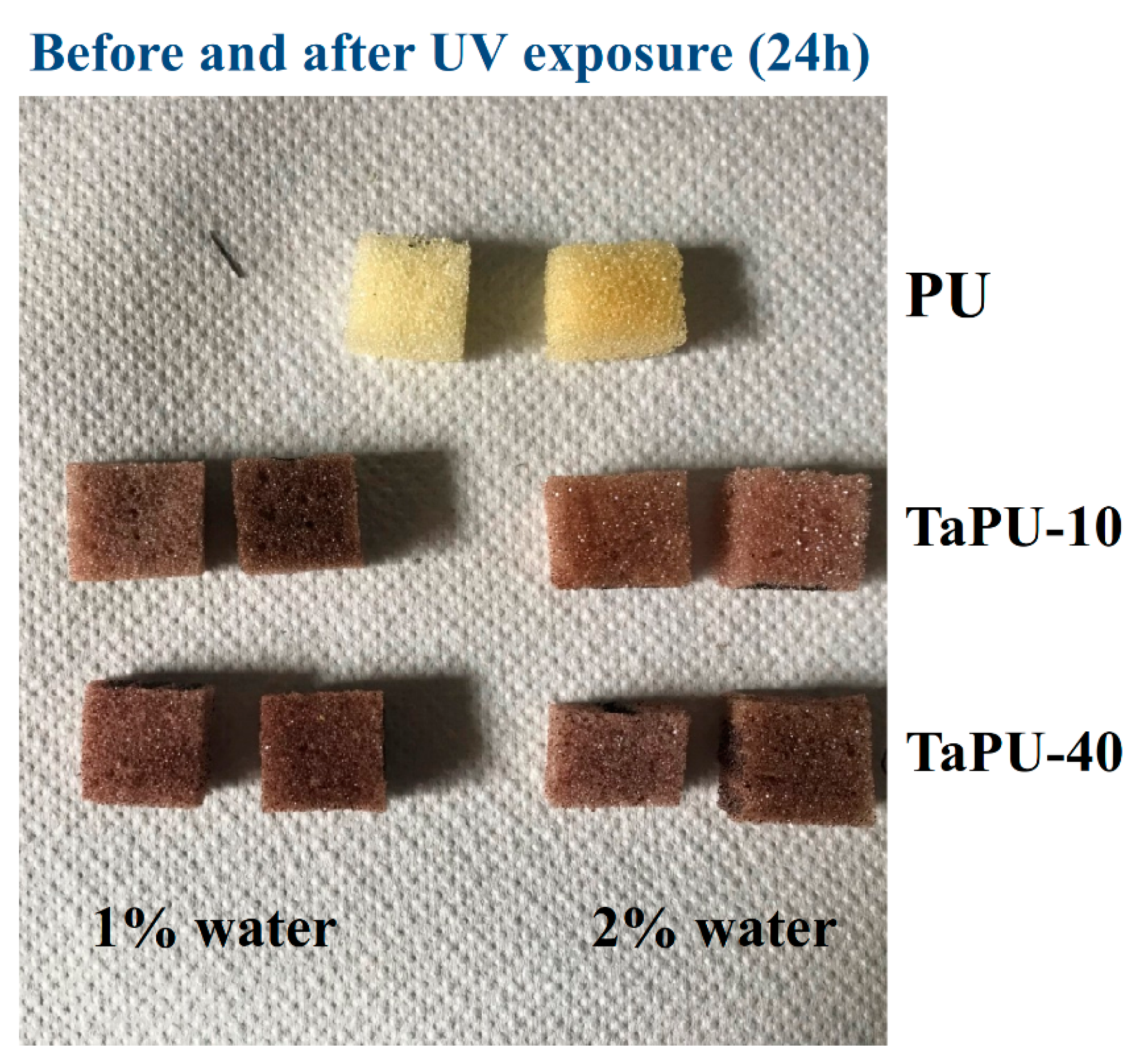

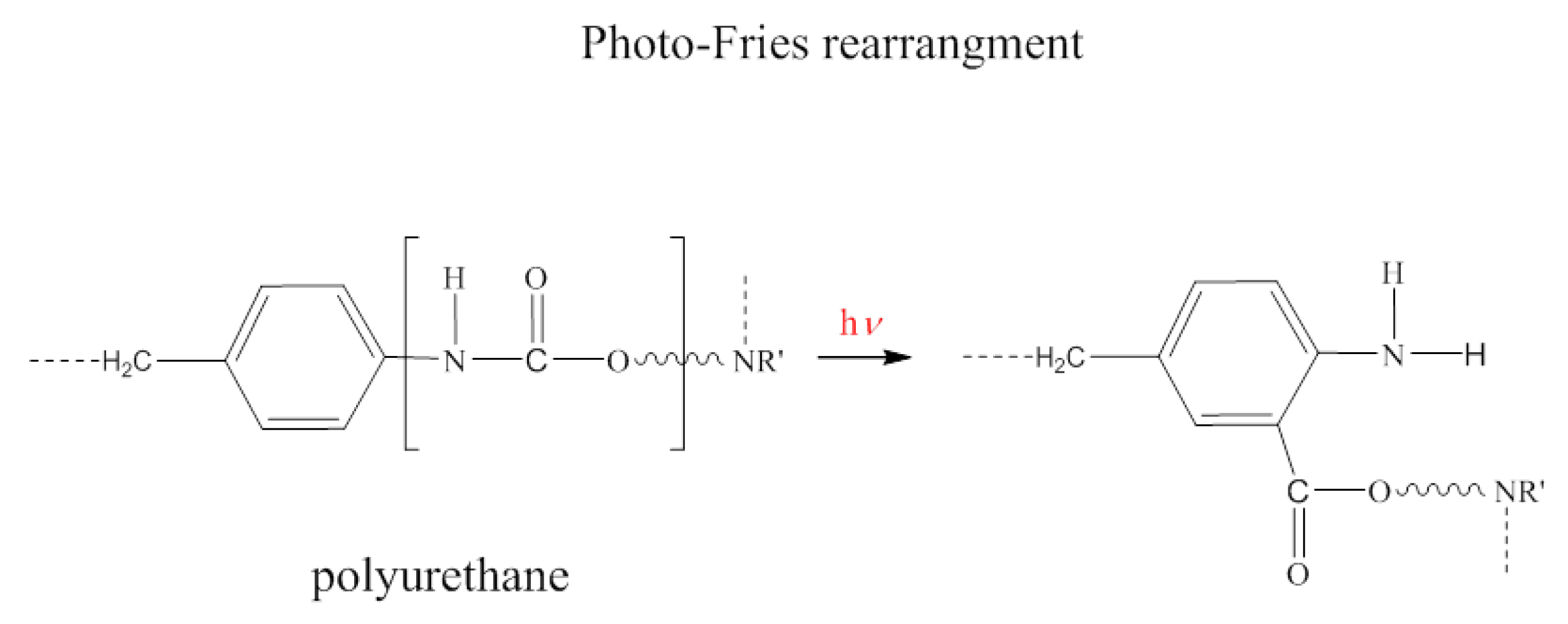

3.5. UV-Treated Foams

4. Conclusions

- The addition of CT to the formulation of the polyurethane foam affected the foaming process, reducing the reaction kinetics and lowering the foam density.

- The cellular morphology was improved by tannin, and more cells with a smaller size were generated.

- Increased water content in the formulation allowed a further reduction of the density, but the cell size was increased. Furthermore, water increased the amount of open cells.

- The mechanical performance of the foams was found to depend on the CT content but not in a linear way. In fact, CT had a reinforcing effect at 10 wt %, but in all other cases, tannin induced a significant reduction in both the compressive modulus and strength. These results are due to a) the increase in the open cell content and b) the presence of CT aggregates, detected in edge sections, that were in proportion with the CT content and limited the reinforcing effect.

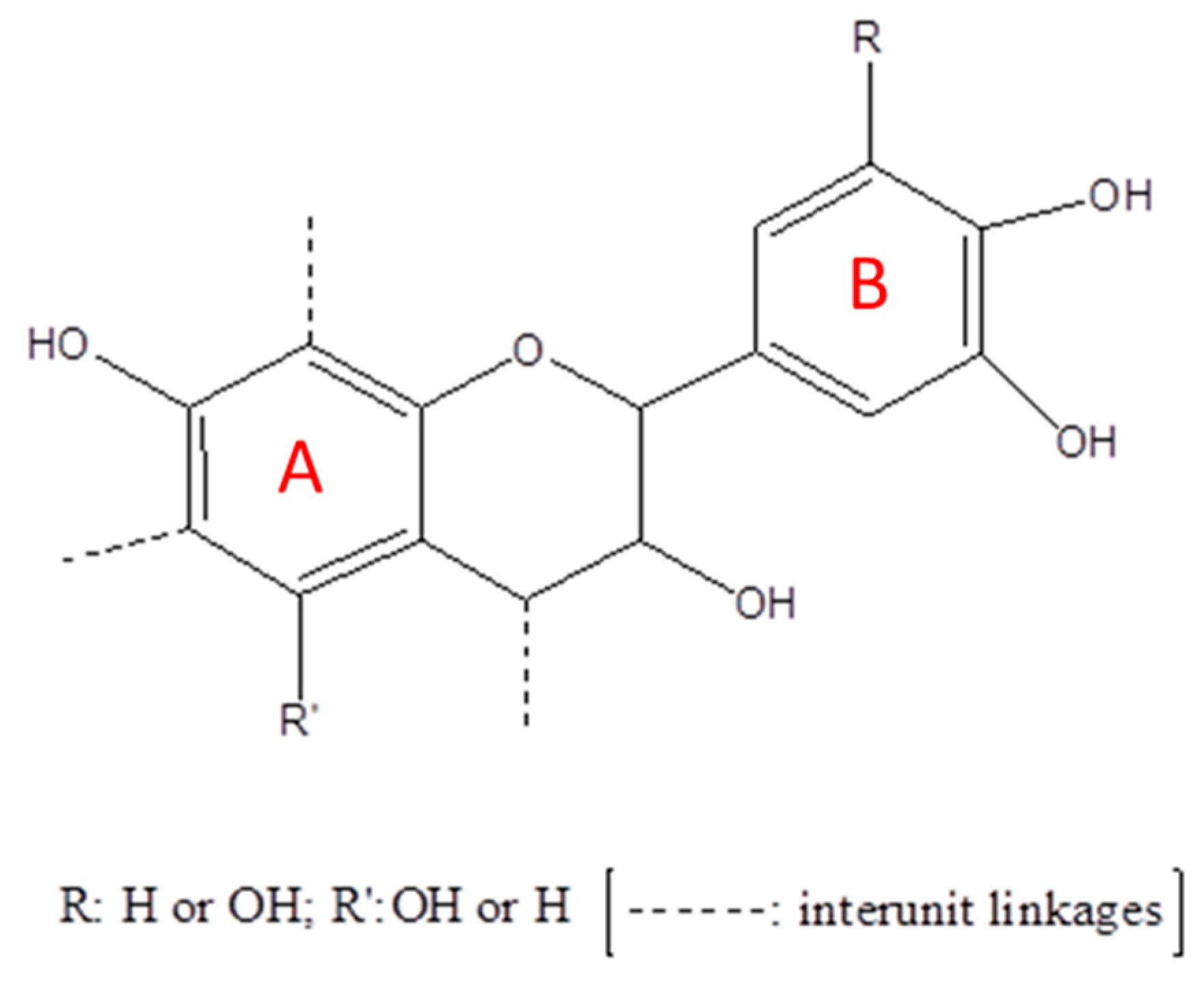

- Foam stability against UV radiation is dependent on the tannin content. The FTIR analysis revealed a strong inhibiting effect of tannin on urethane linkage degradation during the UV treatment, particularly at high CT content. Thanks to its aromatic chemical structure, CT behaves as a sacrificial UV inhibitor because, as an aromatic compound with un-saturated bonds, it absorbs UV radiation through the promotion of π → π * transitions.

- The mechanical properties of the polyurethane foams were significantly affected by the UV exposure. CT strongly reduced the sensitivity to UV radiation, and at a content higher than 20%, the mechanical properties of such samples after UV treatment were almost unchanged.

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Göpferich, A. Mechanisms of polymer degradation and erosion. Biomaterials 1996, 17, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, A.; Sims, D.; Sims, D. Weathering of Polymers; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1983; Available online: https://books.google.it/books?id=3lRzT6iLG-YC (accessed on 10 February 2019).

- White, J.R.; Turnbull, A. Weathering of polymers: Mechanisms of degradation and stabilization, testing strategies and modelling. J. Mater. Sci. 1994, 29, 584–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, M.; Klemchuk, P.P.; Koberstein, J.T. Exploring the effectiveness of SiOx coatings in protecting polymers against photo-oxidation. Polym. Deg. Stab. 2000, 70, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontou, E.; Georgiopoulos, P.; Niaounakis, M. The role of nanofillers on the degradation behavior of polylactic acid. Polym. Compos. 2012, 33, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naddeo, C.; Vertuccio, L.; Barra, G.; Guadagno, L.; Naddeo, C.; Vertuccio, L.; Barra, G.; Guadagno, L. Nano-Charged Polypropylene Application: Realistic Perspectives for Enhancing Durability. Materials 2017, 10, 943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jamalpour, S.; Ghaffarian, S.R.; Jangizehi, A. Effect of matrix−nanoparticle supramolecular interactions on the morphology and mechanical properties of polymer foams. Polym. Int. 2018, 67, 859–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousif, E.; Haddad, R. Photodegradation and photostabilization of polymers, especially polystyrene: Review. Springerplus 2013, 2, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bocchini, S.; Fukushima, K.; di Blasio, A.; Fina, A.; Frache, A.; Geobaldo, F. Polylactic Acid and Polylactic Acid-Based Nanocomposite Photooxidation. Biomacromolecules 2010, 11, 2919–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Białkowska, A.; Mucha, K.; Bakar, M.; Przybylek, M. Effect of hard segments content on the properties, structure and biodegradation of nonisocyanate polyurethane. Polym. Polym. Compos. 2018, 26, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białkowska, A.; Bakar, M.; Marchut-Mikołajczyk, O. Biodegradation of linear and branched nonisocyanate condensation polyurethanes based on 2-hydroxy-naphthalene-6-sulfonic acid and phenol sulfonic acid. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2019, 159, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliviero, M.; Rizvi, R.; Verdolotti, L.; Iannace, S.; Naguib, H.E.; di Maio, E.; Neitzert, H.C.; Landi, G. Dielectric Properties of Sustainable Nanocomposites Based on Zein Protein and Lignin for Biodegradable Insulators. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1605142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Cheng, S.; Yuan, Z.; Leitch, M.; Xu, C. Valorization of bark for chemicals and materials: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 26, 560–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, A. Wood products and green chemistry. Ann. For. Sci. 2016, 73, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kulvik, E. Chestnut wood tannin extract in plywood adhesives. Adhes. Age 1976, 19, 19–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kulvik, E. Chestnut wood tannin extract as cure accelerator for phenol-formaldehyde wood adhesives. Adhes. Age 1977, 20, 33–34. [Google Scholar]

- Drewes, S.E.; Roux, D.G. Condensed tannins. 15. Interrelationships of flavonoid components in wattle-bark extract. Biochem. J. 1963, 87, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roux, D.G.; Paulus, E. Condensed tannins. 7. Isolation of (−)-7: 3′: 4′-trihydroxyflavan-3-ol [(−)-fisetinidol], a naturally occurring catechin from black-wattle heartwood. Biochem. J. 1961, 78, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizzi, A. Advanced Wood Adhesives Technology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Tondi, G.; Pizzi, A. Tannin-based rigid foams: Characterization and modification. Ind. Crops Prod. 2009, 29, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zucker, W.V. Tannins: Does structure determine function? An ecological perspective. Am. Nat. 1983, 121, 335–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Fierro, V.; Pizzi, A.; Du, G.; Celzard, A. Effect of composition and processing parameters on the characteristics of tannin-based rigid foams. Part II: Physical properties. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2010, 123, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celzard, A.; Fierro, V.; Amaral-Labat, G.; Pizzi, A.; Torero, J. Flammability assessment of tannin-based cellular materials. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2011, 96, 477–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duval, A.; Avérous, L. Oxyalkylation of Condensed Tannin with Propylene Carbonate as an Alternative to Propylene Oxide. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016, 4, 3103–3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, M.; Pizzi, A.; Lacoste, C.; Delmotte, L.; Al-Marzouki, F.; Abdalla, S.; Celzard, A. MALDI-TOF and 13C NMR Analysis of Tannin–Furanic–Polyurethane Foams Adapted for Industrial Continuous Lines Application. Polymers 2014, 6, 2985–3004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roux, D.G. Recent advances in the chemistry and chemical utilization of the natural condensed tannins. Phytochemistry 1972, 11, 1219–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, D.G.; Ferreira, D.; Hundt, H.K.L.; Malan, E. Structure, stereochemistry, and reactivity of natural condensed tannins as basis for their extended industrial application. Appl. Polym. Symp. 1975, 28, 335–353. [Google Scholar]

- Grigsby, W.J.; Bridson, J.H.; Lomas, C.; Frey, H. Evaluating Modified Tannin Esters as Functional Additives in Polypropylene and Biodegradable Aliphatic Polyester. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2014, 299, 1251–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samper, M.D.; Fages, E.; Fenollar, O.; Boronat, T.; Balart, R. The potential of flavonoids as natural antioxidants and UV light stabilizers for polypropylene. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2013, 129, 1707–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangeetha, N.J.; Retna, A.M.; Joy, Y.J.; Sophia, A. A review on advanced methods of polyurethane synthesis based on natural resources. J. Chem. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 7, 242–249. [Google Scholar]

- Arbenz, A.; Frache, A.; Cuttica, F.; Avérous, L. Advanced biobased and rigid foams, based on urethane-modified isocyanurate from oxypropylated gambier tannin polyol. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2016, 132, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliviero, M.; Verdolotti, L.; Stanzione, M.; Lavorgna, M.; Iannace, S.; Tarello, M.; Sorrentino, A. Bio-based flexible polyurethane foams derived from succinic polyol: Mechanical and acoustic performances. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 134, 45113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stanzione, M.; Russo, V.; Oliviero, M.; Verdolotti, L.; Sorrentino, A.; di Serio, M.; Tesser, R.; Iannace, S.; Lavorgna, M. Synthesis and characterization of sustainable polyurethane foams based on polyhydroxyls with different terminal groups. Polymer 2018, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, M.C.; Giovando, S.; Pizzi, A.; Pasch, H.; Pretorius, N.; Delmotte, L.; Celzard, A. Flexible-elastic copolymerized polyurethane-tannin foams. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2014, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.-Y.; Lee, W.-J. Characteristics of glycolysis products of polyurethane foams made with polyhydric alcohol liquefied Cryptomeria japonica wood. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2014, 101, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannace, S.; Sorrentino, A. Bio-based and bio-inspired cellular materials. Biofoams Sci. Appl. Bio-Based Cell. Porous Mater. 2015, 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- De Gennaro, B.; Aprea, P.; Colella, C.; Buondonno, A. Comparative ion-exchange characterization of zeolitic and clayey materials for pedotechnical applications—Part 1: Interaction with noxious cations. J. Porous Mater. 2007, 14, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdolotti, L.; Lavorgna, M.; Oliviero, M.; Sorrentino, A.; Iozzino, V.; Buonocore, G.; Iannace, S. Functional zein–siloxane bio-hybrids. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2013, 2, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdolotti, L.; Liguori, B.; Capasso, I.; Errico, A.; Caputo, D.; Lavorgna, M.; Iannace, S. Synergistic effect of vegetable protein and silicon addition on geopolymeric foams properties. J. Mater. Sci. 2015, 50, 2459–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, B.; Cassese, A.; Colella, C. Safe immobilization of Cr (III) in heat-treated zeolite tuff compacts. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 137, 1206–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luna, M.S.; Altobelli, R.; Gioiella, L.; Castaldo, R.; Scherillo, G.; Filippone, G. Role of polymer network and gelation kinetics on the mechanical properties and adsorption capacity of chitosan hydrogels for dye removal. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 2017, 55, 1843–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Pizzi, A.; Cangemi, M.; Fierro, V.; Celzard, A. Flexible natural tannin-based and protein-based biosourced foams. Ind. Crops Prod. 2012, 37, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Shi, X.; Cai, M.; Wu, R.; Wang, M. A novel biodegradable antimicrobial PU foam from wattle tannin. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2003, 90, 2756–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schotman, A.H.M. The Reaction of Isocyanates with Carboxylic Acids and its Application to Polymer Synthesis. Delft University of Technology, 1993. Available online: http://resolver.tudelft.nl/uuid:471daa66-8607-4221-a3a6-cca967887796 (accessed on 10 February 2019).

- Soto, G.D.; Marcovich, N.E.; Mosiewicki, M.A. Flexible polyurethane foams modified with biobased polyols: Synthesis and physical-chemical characterization. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2016, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcovich, N.E.; Kurańska, M.; Prociak, A.; Malewska, E.; Bujok, S. The effect of different palm oil-based bio-polyols on foaming process and selected properties of porous polyurethanes. Polym. Int. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago-Calvo, M.; Tirado-Mediavilla, J.; Ruiz-Herrero, J.L.; Rodríguez-Pérez, M.Á.; Villafañe, F. The effects of functional nanofillers on the reaction kinetics, microstructure, thermal and mechanical properties of water blown rigid polyurethane foams. Polymer 2018, 150, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sernek, M.; Kamke, F.A. Application of dielectric analysis for monitoring the cure process of phenol formaldehyde adhesive. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2007, 27, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, M. Chemistry and Technology of Polyols for Polyurethanes; iSmithers Rapra Publishing: Shawbury, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Prociak, A.; Kurańska, M.; Malewska, E.; Szczepkowski, L.; Zieleniewska, M.; Ryszkowska, J.; Ficoń, J.; Rząsa, A. Biobased polyurethane foams modified with natural fillers. Polimery 2015, 60, 592–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdolotti, L.; di Maio, E.; Lavorgna, M.; Iannace, S. Hydration-induced reinforcement of rigid polyurethane-cement foams: Mechanical and functional properties. J. Mater. Sci. 2012, 47, 6948–6957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, L.J.; Ashby, M.F.; Harley, B.A. Cellular Materials in Nature and Medicine; Cambridge International Science Publishing Ltd.: Cambridge, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rashvand, M.; Ranjbar, Z.; Rastegar, S. Nano zinc oxide as a UV-stabilizer for aromatic polyurethane coatings. Prog. Org. Coat. 2011, 71, 362–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajsic, E.G.; Rek, V.; Sendijarevic, A.; Sendijarevic, V.; Frish, K.C. The effect of different molecular weight of soft segments in polyurethanes on photooxidative stability. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1996, 52, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Vang, C.; Tallman, D.; Bierwagen, G.; Croll, S.; Rohlik, S. Weathering degradation of a polyurethane coating. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2001, 74, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosu, D.; Rosu, L.; Cascaval, C.N. IR-change and yellowing of polyurethane as a result of UV irradiation. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2009, 94, 591–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubakri, A.; Guermazi, N.; Elleuch, K.; Ayedi, H.F. Study of UV-aging of thermoplastic polyurethane material. Mater. Sci. Eng. A. 2010, 527, 1649–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claude, B.; Gonon, L.; Duchet, J.; Verney, V.; Gardette, J.L. Surface cross-linking of polycarbonate under irradiation at long wavelengths. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2004, 83, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oprea, S.; Oprea, V. Mechanical behavior during different weathering tests of the polyurethane elastomers films. Eur. Polym. J. 2002, 38, 1205–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | EtCO/pMDI | Tannin (wt %) * | Water (wt %) ** |

|---|---|---|---|

| PU | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| TaPU-10 | 1 | 10 | 1 |

| TaPU-20 | 1 | 20 | 1 |

| TaPU-30 | 1 | 30 | 1 |

| TaPU-40 | 1 | 40 | 1 |

| PUw | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| TaPU-10w | 1 | 10 | 2 |

| TaPU-20w | 1 | 20 | 2 |

| TaPU-30w | 1 | 30 | 2 |

| TaPU-40w | 1 | 40 | 2 |

| Samples | Induction Time (s) | End of Rise Time (s) | Foam Density (kg/m3) | Mean Cell Size (μm) | Cells Number (×103 cells/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PU | 5 | 16 | 58.6 ± 2.3 | 1150 | 0.7 |

| TaPU-10 | 12 | 43 | 61.5 ± 1.9 | 483 | 8.9 |

| TaPU-20 | 13 | 52 | 60.6 ± 1.8 | 598 | 4.7 |

| TaPU-30 | 20 | 68 | 51.1 ± 1.5 | 598 | 4.7 |

| TaPU-40 | 23 | 70 | 51.1 ± 1.8 | 644 | 3.7 |

| PUw | 3 | 10 | 45.3 ± 2.1 | 1449 | 0.3 |

| TaPU-10w | 5 | 21 | 32.9 ± 1.3 | 920 | 1.3 |

| TaPU-20w | 4 | 20 | 38.4 ± 2.4 | 828 | 1.8 |

| TaPU-30w | 5 | 25 | 48.8 ± 1.4 | 644 | 3.7 |

| TaPU-40w | 6 | 26 | 49.6 ± 1.7 | 552 | 5.9 |

| Samples | Compressive Modulus (kPa) | Specific Modulus (kPa/kg/m3) | Compressive Strength (kPa) | Specific Strength (kPa/kg/m3) | Yield Strain (%) | Critical Strain (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PU | 1475 ± 35 | 25.2 | 179 ± 12 | 3.1 | 19.2 ± 0.9 | 53 ± 3 |

| TaPU-10 | 1640 ± 55 | 26.7 | 185 ± 11 | 3.0 | 18.5 ± 0.9 | 43 ± 3 |

| TaPU-20 | 882 ± 21 | 14.6 | 78 ± 4 | 1.3 | 15.1 ± 0.4 | 56 ± 2 |

| TaPU-30 | 481 ± 10 | 9.4 | 40 ± 3 | 0.8 | 18.3 ± 0.6 | 69 ± 2 |

| TaPU-40 | 298 ± 9 | 6.6 | 33 ± 2 | 0.7 | 14.8 ± 0.5 | 72 ± 4 |

| PUw | 864 ± 19 | 19.1 | 45 ± 6 | 1.0 | 17.2 ± 0.8 | 66 ± 3 |

| TaPU-10w | 704 ± 21 | 21.4 | 41 ± 7 | 1.2 | 16.4 ± 0.5 | 45 ± 3 |

| TaPU-20w | 458 ± 13 | 11.9 | 39 ± 5 | 1.0 | 15.8 ± 0.8 | 72 ± 3 |

| TaPU-30w | 387 ± 11 | 7.9 | 34 ± 4 | 0.7 | 16.2 ± 0.4 | 75 ± 3 |

| TaPU-40w | 262 ± 6 | 5.3 | 28 ± 1 | 0.6 | 16.3 ± 0.6 | 76 ± 3 |

| Exposure Time (h) | Compressive Modulus (kPa) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PU | TaPU-10 | TaPU-20 | TaPU-30 | TaPU-40 | PUw | TaPUw-10 | TaPUw-20 | TaPUw-30 | TaPUw-40 | |

| 0.0 | 1080.6 | 1230.6 | 824.4 | 362.3 | 232.3 | 510.4 | 630.3 | 373.1 | 290.9 | 288.7 |

| 3.0 | 766.1 | 920.8 | 780.3 | 340.2 | 230.4 | 445.6 | 591.2 | 342.6 | 287.4 | 287.2 |

| 6.0 | 526.3 | 790.2 | 735.2 | 331.5 | 228.8 | 391.5 | 580.4 | 322.5 | 283.6 | 287.9 |

| 12.0 | 439.0 | 720.8 | 720.1 | 326.0 | 228.0 | 373.2 | 576.2 | 319.2 | 281.3 | 288.5 |

| 24.0 | 363.3 | 683.4 | 706.2 | 324.3 | 227.7 | 320.7 | 571.0 | 317.1 | 280.9 | 288.6 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oliviero, M.; Stanzione, M.; D’Auria, M.; Sorrentino, L.; Iannace, S.; Verdolotti, L. Vegetable Tannin as a Sustainable UV Stabilizer for Polyurethane Foams. Polymers 2019, 11, 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11030480

Oliviero M, Stanzione M, D’Auria M, Sorrentino L, Iannace S, Verdolotti L. Vegetable Tannin as a Sustainable UV Stabilizer for Polyurethane Foams. Polymers. 2019; 11(3):480. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11030480

Chicago/Turabian StyleOliviero, Maria, Mariamelia Stanzione, Marco D’Auria, Luigi Sorrentino, Salvatore Iannace, and Letizia Verdolotti. 2019. "Vegetable Tannin as a Sustainable UV Stabilizer for Polyurethane Foams" Polymers 11, no. 3: 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym11030480