Theoretical and Experimental Study of LiBH4-LiCl Solid Solution

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

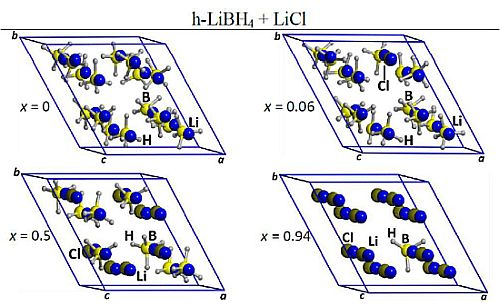

2.1. Optimized Structures of o-LiBH4-Cl and h-LiBH4-Cl Solid Solutions

| o-LiBH4 Pnma | a | b | c | Volume | B-H1 | B-H2 | B-H3 | <B-H> | <HBH> |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exp.a | 7.121 | 4.406 | 6.674 | 209.4 | 1.213 | 1.224 | 1.208 | 1.215 | 109.3 |

| DFT | 7.328 | 4.379 | 6.494 | 208.4 | 1.230 | 1.233 | 1.229 | 1.231 | 109.3 |

| DFT -LiBH4 + LiCl | |||||||||

| o-Li(BH4)0.75Cl0.25 | 7.255 | 4.314 | 6.472 | 202.6 | 1.232 | 1.235 | 1.228 | 1.232 | 108.8 |

| o-Li(BH4)0.5Cl0.5/C1 | 7.111 | 4.245 | 6.538 | 197.3 | 1.228 | 1.234 | 1.225 | 1.229 | 109.0 |

| o-Li(BH4)0.5Cl0.5/C2 | 7.207 | 4.250 | 6.425 | 196.8 | 1.228 | 1.235 | 1.228 | 1.230 | 109.0 |

| o-Li(BH4)0.5Cl0.5/C3 | 7.181 | 4.241 | 6.477 | 197.2 | 1.231 | 1.234 | 1.227 | 1.232 | 108.0 |

| o-Li(BH4)0.25Cl0.75 | 7.079 | 4.161 | 6.538 | 192.7 | 1.226 | 1.234 | 1.226 | 1.232 | 108.9 |

| h-LiBH4 P63mc | |||||||||

| Exp.a | 4.267 | 4.267 | 6.922 | 109.1 | 0.962 | 1.024 | 1.024 | 1.003 | 108.4 |

| DFT | 4.216 | 4.216 | 6.291 | 96.8 | 1.220 | 1.223 | 1.223 | 1.222 | 109.4 |

| DFT supercell | 8.297 | 8.289 | 13.333 | 793.2 | - | - | - | 1.229 | 109.5 |

| DFT h-LiBH4 + LiCl | |||||||||

| h-Li(BH4)0.94Cl0.06 | 8.256 | 8.274 | 13.238 | 782.8 | - | - | - | 1.229 | 109.5 |

| h-Li(BH4)0.5Cl0.5 | 8.016 | 8.067 | 12.740 | 718.1 | - | - | - | 1.228 | 109.5 |

| h-Li(BH4)0.06Cl0.94 | 7.886 | 7.888 | 12.493 | 672.9 | 1.220 | 1.223 | - | 1.222 | 109.5 |

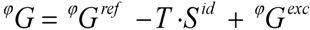

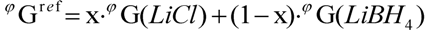

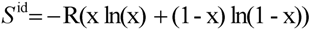

2.2. Thermodynamics of the Solid Solution Formation

2.3. Structural Properties of o-Li(BH4)1−xClx and h-Li(BH4)1−yCly

2.3.1. Computational Study of the o-Li(BH4)1−xClx and h-Li(BH4)1−yCly Vibrational Properties

2.3.2. Experimental Study of LiBH4-LiCl Mixture and Solid Solution

| Molar fraction, mol% | |

|---|---|

| LiBH4-LiCl (1:1) S1 hm | |

| LiClo-LiBH4 | 4456 |

| LiBH4-LiCl (1:1) S1 hm, annealed | |

| LiClo-Li(BH4)0.90Cl0.10h-Li(BH4)0.96Cl0.04 | 344323 |

3. Calculations

3.1. Ab Initio

3.2. CALPHAD

with Ω = 5.940 kJ·mol−1.

with Ω = 5.940 kJ·mol−1. with Ω = −4.827 kJ·mol−1kJ·mol−1.

with Ω = −4.827 kJ·mol−1kJ·mol−1.4. Experimental Section

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Yin, L.; Wang, P.; Fang, Z.; Huiming, C. Thermodynamically tuning LiBH4 by fluorine anion doping for hydrogen storage: A density functional study. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2008, 450, 318–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corno, M.; Pinatel, E.; Ugliengo, P.; Baricco, M. A computational study on the effect of fluorine substitution in LiBH4. J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 509S, S679–S683. [Google Scholar]

- Brinks, H.W.; Fossdal, A.; Hauback, B.C. Adjustment of the stability of complex hydrides by anion substitution. J. Phys. Chem. C 2008, 112, 5658–5661. [Google Scholar]

- Au, M.; Spencer, W.; Jurgensen, A.; Zeigler, C. Hydrogen storage properties of modified lithium borohydrides. J. Alloys Compd. 2008, 462, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.J.; Liu, B.H. Hydrogen desorption from LiBH4 destabilized by chlorides of transition metal Fe, Co, and Ni. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2010, 35, 7288–7294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.; Lee, Y.-S.; Suh, J.Y.; Shim, J.H.; Cho, Y.W. Metal halide doped metal borohydrides for hydrogen storage: The case of Ca(BH4)2–CaX2 (X = F, Cl) mixture. J. Alloys Compd. 2010, 506, 721–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rude, L.H.; Nielsen, T.K.; Ravnsbaek, D.B.; Boesenberg, U.; Ley, M.B.; Richter, B.; Arnbjerg, L.M.; Dornheim, M.; Filinchuk, Y.; Besenbacher, F.; et al. Tailoring properties of borohydrides for hydrogen storage: A review. Phys. Status Solidi (a) 2011, 208, 1754–1773. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo, M.; Remhof, A.; Martelli, P.; Caputo, R.; Ernst, M.; Miura, Y.; Sato, T.; Oguchi, H.; Maekawa, H.; Takamura, H.; et al. Complex hydrides with (BH(4))(-) and (NH(2))(-) anions as new lithium fast-ion conductors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 16389–16391. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo, M.; Nakamori, Y.; Orimo, S.; Maekawa, H.; Takamura, H. Lithium superionic conduction in lithium borohydride accompanied by structural transition. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 91, 224103–224105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maekawa, H.; Matsuo, M.; Takamura, H.; Ando, M.; Noda, Y.; Karahashi, T.; Orimo, S.I. Halide-stabilized LiBH4, a room-temperature lithium fast-ion conductor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 894–895. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo, M.; Takamura, H.; Maekawa, H.; Li, H.W.; Orimo, S. Stabilization of lithium superionic conduction phase and enhancement of conductivity of LiBH4 by LiCl addition. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 94, 084103–084105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnbjerg, L.M.; Ravnsbaek, D.B.; Filinchuk, Y.; Vang, R.T.; Cerenius, Y.; Besenbacher, F.; Jorgensen, J.E.; Jakobsen, H.J.; Jensen, T.R. Structure and dynamics for LiBH4-LiCl solid solutions. Chem. Mater. 2009, 21, 5772–5782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguchi, H.; Matsuo, M.; Hummelshoj, J.S.; Vegge, T.; Norskov, J.K.; Sato, T.; Miura, Y.; Takamura, H.; Maekawa, H.; Orimo, S. Experimental and computational studies on structural transitions in the LiBH4-LiI pseudobinary system. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 94, 141912/1–141912/3. [Google Scholar]

- Rude, L.H.; Groppo, E.; Arnbjerg, L.M.; Ravnsbaek, D.B.; Malmkjaer, R.A.; Filinchuk, Y.; Baricco, M.; Besenbacher, F.; Jensen, T.R. Iodide substitution in lithium borohydride, LiBH(4)-LiI. J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 509, 8299–8305. [Google Scholar]

- Rude, L.H.; Zavorotynska, O.; Arnbjerg, L.M.; Ravnsbaek, D.B.; Malmkjaer, R.A.; Grove, H.; Hauback, B.C.; Baricco, M.; Filinchuk, Y.; Besenbacher, F.; et al. Bromide substitution in lithium borohydride, LiBH(4)-LiBr. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 15664–15672. [Google Scholar]

- Dovesi, R.; Saunders, V.R.; Roetti, C.; Zicovich-Wilson, C.M.; Pascale, F.; Civalleri, B.; Doll, K.; Harrison, N.M.; Bush, I.J.; D’Arco, P.; et al. CRYSTAL2009 User’s Manual; University of Torino: Torino, Italy, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fonneløp, J.E.; Corno, M.; Grove, H.; Pinatel, E.; Sorby, M.H.; Ugliengo, P.; Baricco, M.; Hauback, B.C. Experimental and computational investigations on the AlH(3)/AlF(3) system. J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 509, 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Bergerhoff, G.; Brown, I.D. Crystallographic Databases; Allen, F.H., Bergerhoff, G., Sievers, R., Eds.; International Union of Crystallography: Chester, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Zavorotynska, O.; Corno, M.; Damin, A.; Spoto, G.; Ugliengo, P.; Baricco, M. Vibrational properties of MBH(4) and MBF(4) crystals (M = Li, Na, K): A combined DFT, infrared, and raman study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 18890–18900. [Google Scholar]

- Lide, D.R. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics, 88th ed; CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hartman, M.R.; Rush, J.J.; Udovic, T.J.; Bowman, R.C.; Hwang, S.J. Structure and vibrational dynamics of isotopically labeled lithium borohydride using neutron diffraction and spectroscopy. J. Solid State Chem. 2007, 180, 1298–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miwa, K.; Ohba, N.; Towata, S.; Nakamori, Y.; Orimo, S. First-principles study on lithium borohydride LiBH4. Phys. Rev. B 2004, 69, 245120/1–245120/8. [Google Scholar]

- Gomes, S.; Hagemann, H.; Yvon, K. Lithium boro-hydride LiBH4 II. Raman spectroscopy. J. Alloys Compd. 2002, 346, 206–210. [Google Scholar]

- El Kharbachi, A.; Nuta, I.; Hodaj, F.; Baricco, M. Above room temperature heat capacity and phase transition of lithium tetrahydroborate. Thermochim. Acta 2011, 520, 75–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, T.E.C.; Grant, D.M.; Telepeni, I.; Yu, X.B.; Walker, G.S. The decomposition pathways for LiBD4-MgD2 multicomponent systems investigated by in situ neutron diffraction. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 472, 559–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukas, H.L.; Fries, S.G.; Sundman, B. Computational Thermodynamics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Andresen, E.R.; Gremaud, R.; Borgschulte, A.; Ramirez-Cuesta, A.J.; Zuttel, A.; Hamm, P. Vibrational Dynamics of LiBH4 by Infrared Pump-Probe and 2D Spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 12838–12846. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, K.B.; McQuaker, N.R. Low temperature infrared and raman spectra of lithium borohydride. Can. J. Chem. 1971, 49, 3282–3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orimo, S.; Nakamori, Y.; Zuttel, A. Material properties of MBH4 (M=Li, Na,and K). Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2004, 108, 51–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagemann, H.; Filinchuk, Y.; Chernyshov, D.; van Beek, W. Lattice anharmonicity and structural evolution of LiBH4: an insight from Raman and X-ray diffraction experiments. Phase Transit. 2009, 82, 344–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascale, F.; Zicovich-Wilson, C.M.; Gejo, F.L.; Civalleri, B.; Orlando, R.; Dovesi, R. The calculation of the vibrational frequencies of crystalline compounds and its implementation in the CRYSTAL code. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 888–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zicovich-Wilson, C.M.; Torres, M.R.; Pascale, F.; Valenzano, L.; Orlando, R.; Dovesi, R. Ab initio simulation of the IR spectra of pyrope, grossular, and andradit. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29, 2268–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civalleri, B.; Zicovich-Wilson, C.M.; Valenzano, L.; Ugliengo, P. B3LYP augmented with an empirical dispersion term (B3LYP-D*) as applied to molecular crystals. CrystEngComm 2008, 10, 405–410. [Google Scholar]

- Grimme, S. Semiempirical GGA-type density functional constructed with a long-range dispersion correction. J. Comput. Chem. 2006, 27, 1787–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinsdale, A. SGTE data for pure elements. Calphad 1991, 15, 317–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SGTE substance database V 4.1. Available online: http://www.crct.polymtl.ca/fact/documentation/sgps_list.htm (accessed on 2 February 2012).

- Rodriguez-Carvajal, J. FULLPROF SUITE: LLB; Sacley & LCSIM: Rennes, France, 2003. [Google Scholar]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Zavorotynska, O.; Corno, M.; Pinatel, E.; Rude, L.H.; Ugliengo, P.; Jensen, T.R.; Baricco, M. Theoretical and Experimental Study of LiBH4-LiCl Solid Solution. Crystals 2012, 2, 144-158. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst2010144

Zavorotynska O, Corno M, Pinatel E, Rude LH, Ugliengo P, Jensen TR, Baricco M. Theoretical and Experimental Study of LiBH4-LiCl Solid Solution. Crystals. 2012; 2(1):144-158. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst2010144

Chicago/Turabian StyleZavorotynska, Olena, Marta Corno, Eugenio Pinatel, Line H. Rude, Piero Ugliengo, Torben R. Jensen, and Marcello Baricco. 2012. "Theoretical and Experimental Study of LiBH4-LiCl Solid Solution" Crystals 2, no. 1: 144-158. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst2010144

APA StyleZavorotynska, O., Corno, M., Pinatel, E., Rude, L. H., Ugliengo, P., Jensen, T. R., & Baricco, M. (2012). Theoretical and Experimental Study of LiBH4-LiCl Solid Solution. Crystals, 2(1), 144-158. https://doi.org/10.3390/cryst2010144