A New Tool in the Quest for Biocompatible Phthalocyanines: Palladium Catalyzed Aminocarbonylation for Amide Substituted Phthalonitriles and Illustrative Phthalocyanines Thereof

Abstract

:1. Introduction

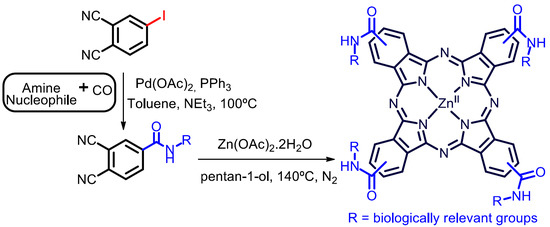

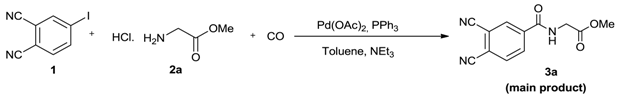

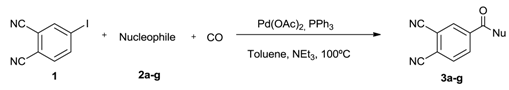

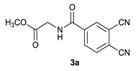

2. Results and Discussion

3. Experimental

3.1. Materials and Methods

3.2. General Procedure for Synthesis of CARBOXAMIDE Substituted Phthalonitriles 3a–g

3.3. General Procedure for Synthesis of Carboxamide Substituted Phthalocyanines

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References and Notes

- Lovell, J.F.; Liu, T.W.B.; Chen, J.; Zheng, G. Activatable Photosensitizers for Imaging and Therapy. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 2839–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Josefsen, L.B.; Boyle, R.W. Unique Diagnostic and Therapeutic Roles of Porphyrins and Phthalocyanines in Photodynamic Therapy, Imaging and Theranostics. Theranostics 2012, 2, 916–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jiblaoui, A.; Leroy-Lhez, S.; Ouk, T.S.; Grenier, K.; Sol, V. Novel polycarboxylate porphyrins: Synthesis, characterization, photophysical properties and preliminary antimicrobial study against Gram-positive bacteria. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 25, 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvete, M.J.F.; Pinto, S.M.A.; Pereira, M.M.; Geraldes, C.F.G.C. Metal coordinated pyrrole-based macrocycles as contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging technologies: Synthesis and applications. Coordin. Chem. Rev. 2017, 333, 82–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvete, M.J.F.; Simoes, A.V.C.; Henriques, C.A.; Pinto, S.M.A.; Pereira, M.M. Tetrapyrrolic Macrocycles: Potentialities in Medical Imaging Technologies. Curr. Org. Synth. 2014, 11, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekdas, D.A.; Garifullin, R.; Senturk, B.; Zorlu, Y.; Gundogdu, U.; Atalar, E.; Tekinay, A.B.; Chernonosov, A.A.; Yerli, Y.; Dumoulin, F.; et al. Design of a Gd-DOTA-Phthalocyanine Conjugate Combining MRI Contrast Imaging and Photosensitization Properties as a Potential Molecular Theranostic. Photochem. Photobiol. 2014, 90, 1376–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sorokin, A.B. Phthalocyanine Metal Complexes in Catalysis. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 8152–8191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvete, M.J.F.; Silva, M.; Pereira, M.M.; Burrows, H.D. Inorganic helping organic: Recent advances in catalytic heterogeneous oxidations by immobilised tetrapyrrolic macrocycles in micro and mesoporous supports. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 22774–22789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.L.; Diau, E.W.G. Porphyrin-sensitized solar cells. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 291–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbani, M.; Gratzel, M.; Nazeeruddin, M.K.; Torres, T. Meso-Substituted Porphyrins for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 12330–12396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayda, M.; Dumoulin, F.; Hug, G.L.; Koput, J.; Gorniaka, R.; Wojcik, A. Fluorescent H-aggregates of an asymmetrically substituted mono-amino Zn(II) phthalocyanine. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 1914–1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiblaoui, A.; Brevier, J.; Ducourthial, G.; Gonzalez-Nunez, H.; Baudequin, C.; Sol, V.; Leroy-Lhez, S. Modulation of intermolecular interactions in new pyrimidine-porphyrin system as two-photon absorbing photosensitizers. Tetrahedron 2015, 71, 2428–2434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dini, D.; Calvete, M.J.F.; Hanack, M. Nonlinear Optical Materials for the Smart Filtering of Optical Radiation. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 13043–13233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvete, M.J.F.; Dini, D. Conjugated macrocyclic materials with photoactivated optical absorption for the control of energy transmission delivered by pulsed radiations. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 2018, 35, 56–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumoulin, F.; Durmus, M.; Ahsen, V.; Nyokong, T. Synthetic pathways to water-soluble phthalocyanines and close analogs. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2010, 254, 2792–2847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, S.M.A.; Tome, V.A.; Calvete, M.J.F.; Pereira, M.M.; Burrows, H.D.; Cardoso, A.M.S.; Pallier, A.; Castro, M.M.C.A.; Toth, E.; Geraldes, C.F.G.C. The quest for biocompatible phthalocyanines for molecular imaging: Photophysics, relaxometry and cytotoxicity studies. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2016, 154, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanack, M.; Crucius, G.; Calvete, M.J.F.; Ziegler, T. Glycosylated Metal Phthalocyanines. Curr. Org. Synth. 2014, 11, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobo, A.C.S.; Silva, A.D.; Tome, V.A.; Pinto, S.M.A.; Silva, E.F.F.; Calvete, M.J.F.; Gomes, C.M.F.; Pereira, M.M.; Arnaut, L.G. Phthalocyanine Labels for Near-Infrared Fluorescence Imaging of Solid Tumors. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 4688–4696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simoes, A.V.C.; Adamowicz, A.; Dabrowski, J.M.; Calvete, M.J.F.; Abreu, A.R.; Stochel, G.; Arnaut, L.G.; Pereira, M.M. Amphiphilic meso(sulfonate ester fluoroaryl)porphyrins: Refining the substituents of porphyrin derivatives for phototherapy and diagnostics. Tetrahedron 2012, 68, 8767–8772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roffey, S.J.; Obach, R.S.; Gedge, J.I.; Smith, D.A. What is the objective of the mass balance study? A retrospective analysis of data in animal and human excretion studies employing radiolabeled drugs. Drug Metab. Rev. 2007, 39, 17–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ball, D.J.; Mayhew, S.; Wood, S.R.; Griffiths, J.; Vernon, D.I.; Brown, S.B. A comparative study of the cellular uptake and photodynamic efficacy of three novel zinc phthalocyanines of differing charge. Photochem. Photobiol. 1999, 69, 390–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, N.; Borlak, J. Drug-induced phospholipidosis. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 5533–5540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- El-Faham, A.; Albericio, F. Peptide Coupling Reagents, More than a Letter Soup. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 6557–6602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunetz, J.R.; Magano, J.; Weisenburger, G.A. Large-Scale Applications of Amide Coupling Reagents for the Synthesis of Pharmaceuticals. Org. Process. Res. Dev. 2016, 20, 140–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattabiraman, V.R.; Bode, J.W. Rethinking amide bond synthesis. Nature 2011, 480, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osburn, E.J.; Chau, L.K.; Chen, S.Y.; Collins, N.; OBrien, D.F.; Armstrong, N.R. Novel amphiphilic phthalocyanines: Formation of Langmuir-Blodgett and cast thin films. Langmuir 1996, 12, 4784–4796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, R.N.; Qiu, Y.; Tian, S.F.; Wang, S.Q.; Song, X.Q. Oxidative biomacromolecular damage from novel phthalocyanine. Sci. China Ser. B 1998, 41, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhalenko, S.A.; Solov’eva, L.I.; Luk’yanets, E.A. Phthalocyanines and related compounds: XXXVII. Synthesis of covalent conjugates of carboxy-substituted phthalocyanines with alpha-amino acids. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2004, 74, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haywood-Small, S.L.; Vernon, D.I.; Griffiths, J.; Schofield, J.; Brown, S.B. Phthalocyanine-mediated photodynamic therapy induces cell death and a G(0)/G(1) cell cycle arrest in cervical cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2006, 339, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drechsler, U.; Pfaff, M.; Hanack, M. Synthesis of novel functionalised zinc phthalocyanines applicable in photodynamic therapy. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 1999, 3441–3453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibrian-Vazquez, M.; Ortiz, J.; Nesterova, I.V.; Fernandez-Lazaro, F.; Sastre-Santos, A.; Soper, S.A.; Vicente, M.G.H. Synthesis and properties of cell-targeted Zn(II)-phthalocyanine-peptide conjugates. Bioconjugate Chem. 2007, 18, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ongarora, B.G.; Fontenot, K.R.; Hu, X.K.; Sehgal, I.; Satyanarayana-Jois, S.D.; Vicente, D.G.H. Phthalocyanine-Peptide Conjugates for Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Targeting. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 3725–3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubuc, C.; Langlois, R.; Benard, F.; Cauchon, N.; Klarskov, K.; Tone, P.; van Lier, J.E. Targeting gastrin-releasing peptide receptors of prostate cancer cells for photodynamic therapy with a phthalocyanine-bombesin conjugate. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 2424–2427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, H.; Ait-Mohand, S.; Gosselin, S.; van Lier, J.E.; Guerin, B. Phthalocyanine-Peptide Conjugates via Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 1887–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Zhou, S.Y.; Chen, J.C.; Deng, Y.C.; Luo, Z.P.; Chen, H.W.; Hamblin, M.R.; Huang, M.D. Pentalysine beta-Carbonylphthalocyanine Zinc: An Effective Tumor-Targeting Photosensitizer for Photodynamic Therapy. Chemmedchem 2010, 5, 890–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montalbetti, C.A.G.N.; Falque, V. Amide bond formation and peptide coupling. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 10827–10852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.Y.; Kim, Y.A. Recent development of peptide coupling reagents in organic synthesis. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 2447–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenberg, A.; Heck, R.F. Palladium-Catalyzed Formylation of Aryl, Heterocyclic, and Vinylic Halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1974, 96, 7761–7764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriele, B.; Veltri, L.; Mancuso, R.; Carfagna, C. Cascade Reactions: A Multicomponent Approach to Functionalized Indane Derivatives by a Tandem Palladium- Catalyzed Carbamoylation/Carbocylization Process. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2014, 356, 2547–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veltri, L.; Mancuso, R.; Altomare, A.; Gabriele, B. Divergent Multicomponent Tandem Palladium-Catalyzed Aminocarbonylation-Cyclization Approaches to Functionalized Imidazothiazinones and Imidazothiazoles. ChemCatChem 2015, 7, 2206–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veltri, L.; Grasso, G.; Rizzi, R.; Mancuso, R.; Gabriele, B. Palladium-Catalyzed Carbonylative Multicomponent Synthesis of Functionalized Benzimidazothiazoles. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2016, 5, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veltri, L.; Giofrè, S.V.; Devo, P.; Romeo, R.; Dobbs, A.P.; Gabriele, B. A Palladium Iodide-Catalyzed Oxidative Aminocarbonylation–Heterocyclization Approach to Functionalized Benzimidazoimidazoles. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 1680–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabriele, B.; Mancuso, R.; Salerno, G. Oxidative Carbonylation as a Powerful Tool for the Direct Synthesis of Carbonylated Heterocycles. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 2012, 6825–6839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.-F.; Neumann, H.; Beller, M. Synthesis of Heterocycles via Palladium-Catalyzed Carbonylations. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.-F.; Neumann, H.; Beller, M. Palladium-Catalyzed Oxidative Carbonylation Reactions. Chemsuschem 2013, 6, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gadge, S.T.; Bhanage, B.M. Recent developments in palladium catalysed carbonylation reactions. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 10367–10389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Fang, X.; Liu, Q.; Jackstell, R.; Beller, M.; Wu, X.-F. Palladium-Catalyzed Carbonylative Transformation of C(sp3)–X Bonds. ACS Catal. 2014, 4, 2977–2989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalck, P.; Urrutigoïty, M. Recent improvements in the alkoxycarbonylation reaction catalyzed by transition metal complexes. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2015, 431, 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.-F. Palladium-catalyzed carbonylative transformation of aryl chlorides and aryl tosylates. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 83831–83837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.; Wu, X.-F. Palladium-Catalyzed Carbonylative Multicomponent Reactions. Chem.A Eur. J. 2017, 23, 2973–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kollar, L. Modern Carbonylation Methods; Kollar, L., Ed.; Wiley VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nemykin, V.N.; Lukyanets, E.A. Synthesis of substituted phthalocyanines. Arkivoc 2010, 136–208. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.I.; Li, J.Z.; Cho, H.S.; Kim, D.; Bocian, D.F.; Holten, D.; Lindsey, J.S. Synthesis and excited-state photodynamics of phenylethyne-linked porphyrin-phthalocyanine dyads. J. Mater. Chem. 2000, 10, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrilho, R.M.B.; Heguaburu, V.; Schapiro, V.; Pandolfi, E.; Kollar, L.; Pereira, M.M. An efficient route for the synthesis of chiral conduritol-derivative carboxamides via palladium-catalyzed aminocarbonylation of bromocyclohexenetetraols. Tetrahedron 2012, 68, 6935–6940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrilho, R.M.B.; Pereira, M.M.; Takacs, A.; Kollar, L. Systematic study on the catalytic synthesis of unsaturated 2-ketocarboxamides: Palladium-catalyzed double carbonylation of 1-iodocyclohexene. Tetrahedron 2012, 68, 204–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fun, H.K.; Kobkeatthawin, T.; Ruanwas, P.; Chantrapromma, S. (E)-1-(4-Aminophenyl)-3-(2,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)prop-2-en-1-one. Acta Crystallogr. E 2010, 66, O1973-U1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muller, E.; Peczely, G.; Skoda-Foldes, R.; Takacs, E.; Kokotos, G.; Bellis, E.; Kollar, L. Homogeneous catalytic aminocarbonylation of iodoalkenes and iodobenzene with amino acid esters under conventional conditions and in ionic liquids. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takacs, A.; Abreu, A.R.; Peixoto, A.F.; Pereira, M.; Kollar, L. Synthesis of Ortho-alkoxy-aryl Carboxamides via Palladium-Catalyzed Aminocarbonylation. Synth. Commun. 2009, 39, 1534–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.Y.; Zhang, Y.M.; Ma, D.X.; Li, L.; Li, G.H.; Li, G.D.; Shi, Z.; Feng, S.H. A strategy toward constructing a bifunctionalized MOF catalyst: Post-synthetic modification of MOFs on organic ligands and coordinatively unsaturated metal sites. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 6151–6153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasad, Y.R.; Rao, A.S.; Rambabu, R. Synthesis of Some 4′-Amino Chalcones and their Antiinflammatory and Antimicrobial Activity. Asian J. Chem. 2009, 21, 907–914. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, W.W.; Zhu, H.B.; Deng, Q.Y.; Liu, S.L.; Liu, X.Y.; Shen, Y.J.; Tu, T. Design and Development of Ligands for Palladium-Catalyzed Carbonylation Reactions. Synthesis-Stuttgart 2014, 46, 1689–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Fuente, V.; Godard, C.; Claver, C.; Castillon, S. Highly Selective Palladium-Catalysed Aminocarbonylation of Aryl Iodides using a Bulky Diphosphine Ligand. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012, 354, 1971–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennfuhrer, A.; Neumann, H.; Beller, M. Palladium-Catalyzed Carbonylation Reactions of Aryl Halides and Related Compounds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 4114–4133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.F.; Neumann, H.; Beller, M. Selective Palladium-Catalyzed Aminocarbonylation of Aryl Halides with CO and Ammonia. Chem. Eur. J. 2010, 16, 9750–9753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrilho, R.M.B.; Almeida, A.R.; Kiss, M.; Kollar, L.; Skoda-Foldes, R.; Dabrowski, J.M.; Moreno, M.J.S.M.; Pereira, M.M. One-Step Synthesis of Dicarboxamides through Pd-Catalysed Aminocarbonylation with Diamines as N-Nucleophiles. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2015, 1840–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, D.S.; Bradley, R.J. Chemical properties of alcohols and their protein binding sites. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2000, 57, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graton, J.; Besseau, F.; Brossard, A.M.; Charpentier, E.; Deroche, A.; Le Questel, J.Y. Hydrogen-Bond Acidity of OH Groups in Various Molecular Environments (Phenols, Alcohols, Steroid Derivatives, and Amino Acids Structures): Experimental Measurements and Density Functional Theory Calculations. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 13184–13193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atilla, D.; Durmus, M.; Gurek, A.G.; Ahsen, V.; Nyokong, T. Synthesis, photophysical and photochemical properties of poly(oxyethylene)-substituted zinc phthalocyanines. Dalton Trans. 2007, 1235–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sekkat, N.; van den Bergh, H.; Nyokong, T.; Lange, N. Like a Bolt from the Blue: Phthalocyanines in Biomedical Optics. Molecules 2012, 17, 98–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Isago, H. Optical Spectra of Phthalocyanines and Related Compounds: A Guide for Beginners; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| |||||

| Entry | Solvent | CO Pressure (bar) | Temperature (°C) | Time (h) | Conversion (%) b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | toluene | 10 | 65 | 24 | 25 |

| 2 | toluene | 10 | 85 | 24 | >98 |

| 3 | toluene | 10 | 85 | 12 | 70 |

| 4 | toluene | 10 | 100 | 12 | >98 |

| 5 | toluene | 5 | 100 | 12 | >98 |

| 6 | toluene | 5 | 65 | 70 | >97 |

| 7c | DMF | 5 | 100 | 12 | >98 |

| |||||

| Entry | Nucleophile (NuH) | Amine/(1) Ratio (equiv.) | Time (h) | Product | Yield (%) b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

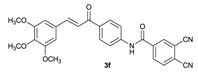

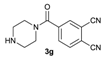

| 1 |  | 1.1 | 12 |  | 65 |

| 2 |  | 1.1 | 12 |  | 54 |

| 3 |  | 1.1 | 12 |  | 59 |

| 4 |  | 3.3 | 4 |  | 74 |

| 5 |  | 1.2 | 3 |  | 80 |

| 6 |  | 1.2 | 25 |  | 70 |

| 7 |  | 6 | 7 |  | 77 |

| |||||

| Compound | Isolated Yield (%) | λmax (nm) (log ε) | Stokes Shift Δstokes (nm) | Emission λmax (nm) | ΦF a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4a | 58 | 350 (4.52); 611 (4.22); 676 (4.87) | 9 | 685 | 0.26 |

| 4c | 65 | 350 (4.14); 610 (3.81); 675 (4.48) | 11 | 686 | 0.31 |

| 4d | 68 | 351 (4.41); 610 (4.49); 676 (5.10) | 9 | 685 | 0.38 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tomé, V.A.; Calvete, M.J.F.; Vinagreiro, C.S.; Aroso, R.T.; Pereira, M.M. A New Tool in the Quest for Biocompatible Phthalocyanines: Palladium Catalyzed Aminocarbonylation for Amide Substituted Phthalonitriles and Illustrative Phthalocyanines Thereof. Catalysts 2018, 8, 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal8100480

Tomé VA, Calvete MJF, Vinagreiro CS, Aroso RT, Pereira MM. A New Tool in the Quest for Biocompatible Phthalocyanines: Palladium Catalyzed Aminocarbonylation for Amide Substituted Phthalonitriles and Illustrative Phthalocyanines Thereof. Catalysts. 2018; 8(10):480. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal8100480

Chicago/Turabian StyleTomé, Vanessa A., Mário J. F. Calvete, Carolina S. Vinagreiro, Rafael T. Aroso, and Mariette M. Pereira. 2018. "A New Tool in the Quest for Biocompatible Phthalocyanines: Palladium Catalyzed Aminocarbonylation for Amide Substituted Phthalonitriles and Illustrative Phthalocyanines Thereof" Catalysts 8, no. 10: 480. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal8100480