The Influence of Excessive Product Packaging on Green Brand Attachment: The Mediation Roles of Green Brand Attitude and Green Brand Image

Abstract

:1. Introduction

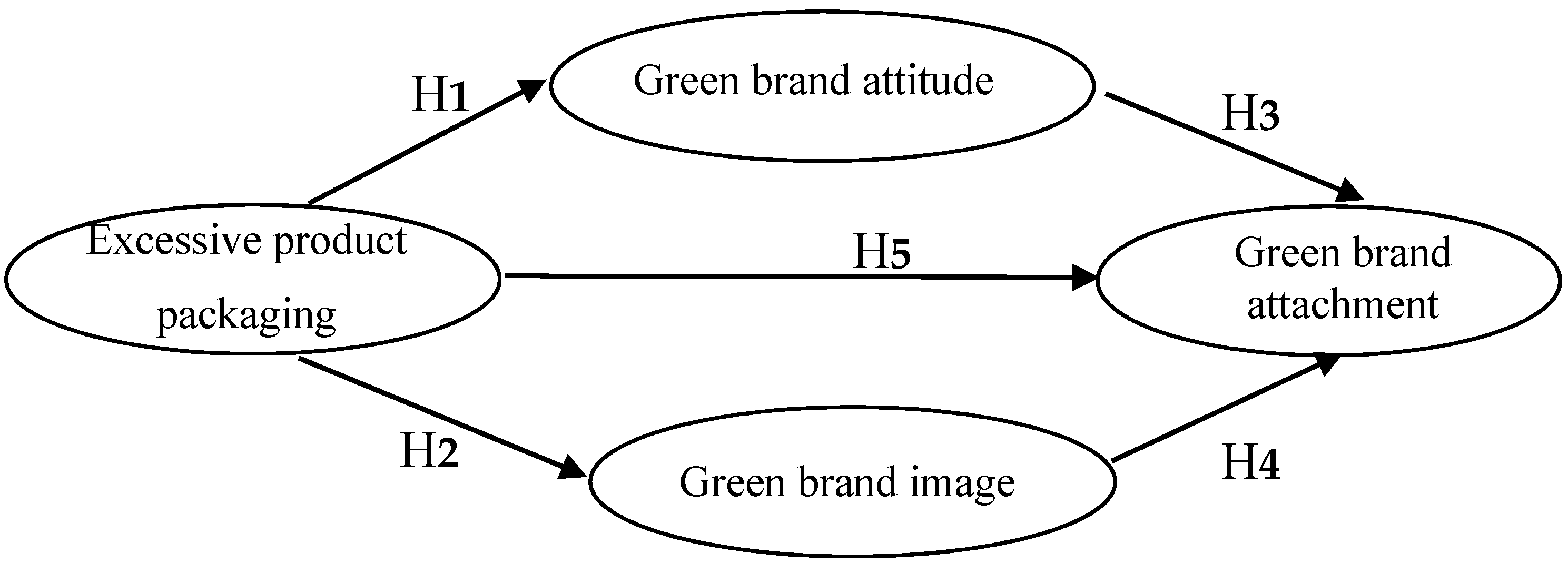

2. Literature Review

2.1. Excessive Packaging

2.2. Green Brand Attitude

2.3. Green Brand Image

2.4. Green Brand Attachment

2.5. Prior Relevant Research Models

3. Hypothesis Development

3.1. The Negative Effect of Excessive Product Packaging on Green Brand Attitude

3.2. The Negative Effect of Excessive Product Packaging on Green Brand Image

3.3. The Positive Effect of Green Brand Attitude on Green Brand Attachment

3.4. The Positive Effect of Green Brand Image on Green Brand Attachment

3.5. The Negative Effect of Excessive Product Packaging on Green Brand Attachment

4. Methodology and Measurement

4.1. Data Collection and the Sample

4.2. Measurements of the Constructs

5. Empirical Results

5.1. The Results of the Measurement Model

5.2. The Results of the Structural Models

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, Y.S.; Lai, S.B.; Wen, C.T. The influence of green innovation performance on corporate advantage in Taiwan. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Wang, S.; Yang, Q. Climate change and global warming. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2010, 9, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Protection Agency. Advancing Sustainable Materials Management: 2014 Fact Sheet; Office of Land and Emergency Management, Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2016.

- Dave West and the Total Environment Centre. Environment Protection and Heritage Council Mid-Term Review of the National Packaging Covenant Report 1: Recycling Performance and Data Integrity; Dave West and the Total Environment Centre: Sydney, Australia, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Enhance environmental commitments and green intangible assets toward green competitive advantages: An analysis of structural equation modeling (SEM). Qual. Quant. 2013, 47, 529–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerman, F. Why Do We Recycle? Markets, Values, and Public Policy; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Dillon, P.S.; Fischer, K. Environmental Management in Corporations: Methods and Motivations; Center for Environmental Management, Tufts University: Medford, MA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lampe, M.; Ellis, S.R.; Drummond, C.K. What companies are doing to meet environmental protection responsibilities: Balancing legal, ethical, and profit concerns? Proc. Int. Assoc. Bus. Soc. 1991, 2, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, A.T.; Morell, D. Leading-Edge Environmental Management: Motivation, Opportunity, Resources, and Processes; JAI Press: Greenwich, CT, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Winn, M. Corporate leadership and policies for the natural environment. Res. Corp. Soc. Perform. Policy 1995, 1, 127–161. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.S. The driver of green innovation and green image–green core competence. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 81, 531–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchi, V.D.; Maria, E.D.; Micelli, S. Environmental strategies, upgrading and competitive advantage in global value chains. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2013, 22, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Greenwash and green trust: The mediation effects of green consumer confusion and green perceived risk. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iles, A. Shifting to green chemistry: The need for innovations in sustainability marketing. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2008, 17, 524–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.B.; Chai, L.T. Attitude towards the environment and green products: Consumers’ perspective. Manag. Sci. Eng. 2010, 4, 27–39. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, C.H. Utilize Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to Explore the Influence of Corporate Environmental Ethics: The Mediation Effect of Green Human Capital. Qual. Quant. 2013, 47, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, K.C. The Nonlinear Effect of Green Innovation on the Corporate Competitive Advantage. Qual. Quant. 2013, 47, 271–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S.; Chang, K.C.; Yeh, S.L.; Cheng, H.I. Green shared vision and green creativity: The mediation roles of green mindfulness and green self-efficacy. Qual. Quant. 2015, 49, 1169–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig-Lewis, N.; Palmer, A.; Dermody, J.; Urbye, A. Consumers’ evaluations of ecological packaging–Rational and emotional approaches. J. Environ. Psychol. 2014, 37, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Besch, K.; Pålsson, H. A Supply Chain Perspective on Green Packaging Development-Theory Versus Practice. Packag. Technol. Sci. 2016, 29, 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, C.Y.; Nie, X.L. An Investigation into Green Logistics and Packaging Design. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 448, 4552–4556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, L.; Vigar-Ellis, D. Consumer understanding, perceptions and behaviours with regard to environmentally friendly packaging in a developing nation. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2014, 38, 642–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.J.; Yang, S.S. Eco-Packaging Solution for Express Service in the Era of Online Shopping. Adv. Mater. Res. 1052, 1052, 578–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bech-Larsen, T. Danish consumers' attitudes to the functional and environmental characteristics of food packaging. J. Consum. Policy 1996, 19, 339–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thøgersen, J. The Demand for Environmentally Friendly Packaging in Germany; MAPP Working Paper; Aarhus School of Business: Aarhus, Denmark, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Ampuero, O.; Vila, N. Consumer perceptions of product packaging. J. Consum. Mark. 2006, 23, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orth, U.R.; Malkewitz, K. Holistic package design and consumer brand impressions. J. Mark. 2008, 72, 64–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durif, F.; Boivin, C.; Julien, C. In search of a green product definition. Innov. Mark. 2010, 6, 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Zhao, Z. Green packaging management of logistics enterprises. Phys. Procedia 2012, 24, 900–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breckler, S.J. Empirical validation of affect, behavior, and cognition as distinct components of attitude. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1984, 47, 1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackwell, R.D.; Miniard, P.W.; Engel, J.F. Consumer Behavior, 10th ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Diekmann, A.; Franzen, A. Umwelthandeln Zwischen Moral Und Okonomie Ecological Behavior among Moral and Economy; University of Bern: Bern, Switzerland, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Geller, E.S. Evaluating Energy Conservation Programs: Is Verbal Report Enough? J. Consum. Res. 1981, 8, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grob, A. A structural model of environmental attitudes and behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Axelrod, L.J.; Lehman, D.R. Responding to environmental concerns: What factors guide individual action? J. Environ. Psychol. 1993, 13, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, I.E.; Corbin, R.M. Perceived consumer effectiveness and faith in others as moderators of environmentally responsible behaviors. J. Public Policy Mark. 1992, 11, 79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Sia, A.P.; Hungerford, H.R.; Tomera, A.N. Selected predictors of responsible environmental behavior: An analysis. J. Environ. Educ. 1986, 17, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A.H.; Chaiken, S. The Psychology of Attitudes; Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers: San Diego, CA, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Abimbola, T.; Trueman, M.; Iglesias, O.; Liu, F.; Li, J.; Mizerski, D.; Soh, H. Self-congruity, brand attitude, and brand loyalty: A study on luxury brands. Eur. J. Mark. 2012, 46, 922–937. [Google Scholar]

- Aaker, D.A. Managing Brand Equity: Capitalizing on the Value of a Brand Name; The Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, J.R. A spreading activation theory of memory. J. Verbal Learn. Verbal Behav. 1983, 22, 261–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, K.L. Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrin, M. The impact of brand extensions on parent brand memory structures and retrieval processes. J. Mark. Res. 1999, 36, 517–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, A.T.; Li, C.K. The moderating effect of brand image on public relations perception and customer loyalty. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2008, 26, 26–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, P.S.; Dick, A.S.; Jain, A.K. Extrinsic and intrinsic cue effects on perceptions of store brand quality. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 28–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, P.F.; Butt, M.M.; Khong, K.W.; Ong, F.S. Antecedents of green brand equity: An integrated approach. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 121, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bearden, W.O.; Etzel, M.J. Reference group influence on product and brand purchase decisions. J. Consum. Res. 1982, 9, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalas, J.E.; Bettman, J.R. Self-construal, reference groups, and brand meaning. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 378–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, F.; Altuna, O.K. The effect of brand extensions on product brand image. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2010, 19, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vraneševic, T.; Stancec, R. The effect of the brand on perceived quality of food products. Br. Food J. 2003, 105, 811–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.C.; Yeh, G.Y.Y.; Hsiao, C.R. The effect of store image and service quality on brand image and purchase intention for private label brands. Australas. Mark. J. 2011, 19, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.S. The drivers of green brand equity: Green brand image, green satisfaction, and green trust. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 93, 307–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, S.E.; Kleine, R.E.; Kernan, J.B. These are a few of my favorite things: Toward an explication of attachment as a consumer behavior construct. Adv. Consum. Res. 1989, 16, 359–366. [Google Scholar]

- Esch, F.R.; Langner, T.; Schmitt, B.H.; Geus, P. Are brands forever? How brand knowledge and relationships affect current and future purchases. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2006, 15, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaplin, L.N.; John, D.R. The development of self-brand connections in children and adolescents. J. Consum. Res. 2005, 32, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escalas, J.E. Narrative Processing: Building Consumer Connections to Brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 2004, 1, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; MacInnis, D.J.; Priester, J.; Eisingerich, A.B.; Iacobucci, D. Brand attachment and brand attitude strength: Conceptual and empirical differentiation of two critical brand equity drivers. J. Mark. 2010, 74, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.W.; MacInnis, D.J.; Priester, J.R. Beyond attitudes: Attachment and consumer behavior. Seoul Natl. J. 2006, 12, 3–36. [Google Scholar]

- Roper, S.; Parker, C. How (and where) the mighty have fallen: Branded litter. J. Mark. Manag. 2006, 22, 473–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roper, S.; Parker, C. The rubbish of marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 2008, 24, 881–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roper, S.; Parker, C. Doing well by doing good: A quantitative investigation of the litter effect. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 2262–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavidge, R.J.; Steiner, G.A. A Model for Predictive Measurements of Advertising Effectiveness. J. Mark. 1961, 25, 59–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavanat, N.; Martinent, G.; Ferrand, A. Sponsor and sponsees interactions: Effects on consumers’ perceptions of brand image, brand attachment, and purchasing intention. J. Sport Manag. 2009, 23, 644–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cretu, A.E.; Brodie, R.J. The influence of brand image and company reputation where manufacturers market to small firms: A customer value perspective. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2007, 36, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, D.A. Sustainable Marketing: Managerial-Ecological Issues; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Swenson, M.R.; Wells, W.D. Useful correlates of pro-environmental behavior. In Social Marketing, Theoretical and Practical Perspectives; Goldberg, M.E., Fishbein, M., Middlestadt, S.E., Eds.; Psychology Press: Hove, UK, 1997; pp. 91–109. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.S.; Seth, S. Accentuating Eco-centric Marketing Philosophy via Green Packaging. Glob. J. Multidiscip. Stud. 2015, 4, 24–29. [Google Scholar]

- Tobler, C.; Visschers, V.H.; Siegrist, M. Eating green. Consumers’ willingness to adopt ecological food consumption behaviors. Appetite 2011, 57, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, J.S.; Stern, P.C.; Elworth, J.T. Personal and contextual influences on household energy adaptations. J. Appl. Psychol. 1985, 70, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guagnano, G.A.; Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T. Influences on attitude-behavior relationships a natural experiment with curbside recycling. Environ. Behav. 1995, 27, 699–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heberlein, T.A. The Land Ethic Realized: Some Social Psychological Explanations for Changing Environmental Attitudes. J. Soc. Issues 1972, 28, 79–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P.C.; Dietz, T.; Black, J.S. Support for environmental protection: The role of moral norms. Popul. Environ. 1985, 8, 204–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, J.H.; Smith, P.M. The “green gap” in proenvironmental attitudes and product availability: Parental tradeoffs in diapering decision-making. In Proceedings of the 1993 Marketing and Public Policy Conference, East Lansing, MI, USA, 1–4 June 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Thøgersen, J. The ethical consumer. Moral norms and packaging choice. J. Consum. Policy 1999, 22, 439–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, D. Shape to Sell: Package Innovation Can Boost Revenue, Decrease Cost and Build Brand. Beverage World 1997, 116, 91–92. [Google Scholar]

- Klimchuk, M.R.; Krasovec, S.A. Packaging Design: Successful Product Branding from Concept to Self; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, V.; Abidi, N.; Bansal, T.; Jain, R.K. Green supply chain management initiatives by IT companies in India. IUP J. Oper. Manag. 2013, 12, 6–24. [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer, M.; Shaver, P.R. The attachment behavioral system in adulthood: Activation, psychodynamics, and interpersonal processes. In Advances in Experimental Social Psychology; Zanna, M.P., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003; Volume 35, pp. 53–152. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, B. The consumer psychology of brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 2012, 22, 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Chen, Q.; Alden, D.L. Time will tell: Managing post-purchase changes in brand attitude. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2016, 44, 791–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, S. Consumers & their brands: Developing relationship theory in consumer research. J. Consum. Res. 1998, 24, 343–353. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, S.; Kozinets, R.V.; Sherry, J.F., Jr. Teaching old brands new tricks: Retro branding and the revival of brand meaning. J. Mark. 2003, 67, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Olaru, D.; Li, J. Self-congruity and brand attitude: A study of local and foreign car brands in China. Proceeding of the 2008 Global Marketing Conference, Shanghai, China, 20–23 March 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.S.; Motion, J.; Conroy, D. Anti-consumption and brand avoidance. J. Bus. Res. 2009, 62, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreda, A.; Nusair, K.; Wang, Y.; Bigihan, A.; Okumus, F. Brand emotional attachment in travel social network websites: The long-term goal for travel organizations. In Proceedings of the 18th Annual Graduate Education and Graduate Student Research Conference in Hospitality and Tourism, Washington, DC, USA, 3–5 January 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Levy, S.J. Symbols for sale. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1959, 37, 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Dittmar, H. The Social Psychology of Material Possessions: To Have Is to Be; Harvester Wheatsheaf: Hemel Hempstead, UK, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Underwood, R.L. The communicative power of product packaging: Creating brand identity via lived and mediated experience. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2003, 11, 62–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotler, P.; Armstrong, G.; Saunders, J.; Wong, V. Principles of Marketing, 2nd European ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Warlop, L.; Ratneshwar, S.; Van Osselaer, S.M. Distinctive brand cues and memory for product consumption experiences. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2005, 22, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokka, J.; Uusitalo, L. Preference for green packaging in consumer product choices—Do consumers care? Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2008, 32, 516–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R.; Stayman, D.M. The Role of Mood in Advertising Effectiveness. J. Consum. Res. 1990, 17, 203–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgarth, C. “This theatre is a part of me” contrasting brand attitude and brand attachment as drivers of audience behavior. Arts Mark. Int. J. 2014, 4, 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Daugherty, T.; Biocca, F. Impact of 3-D advertising on product knowledge, brand attitude, and purchase intention: The mediating role of presence. J. Advert. 2002, 31, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padgett, D.; Allen, D. Communicating Experiences: A Narrative Approach to Creating Service Brand Image. J. Advert. 1997, 26, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, M.; MacInnis, D.J.; Park, C.W. The ties that bind: Measuring the strength of consumers’ emotional attachments to brands. J. Consum. Psychol. 2005, 15, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 6. [Google Scholar]

- DeVellis, R.F. Scale development: Theory and Applications; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2012; Volume 26. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, C.A. Toward a framework of product placement: Theoretical propositions. Adv. Consum. Res. 1988, 25, 357–362. [Google Scholar]

| Constructs | Items | λ | Cronbach’s α | AVE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Excessive product packaging (Rokka and Uusitalo [92]) | GP1: You need to spend a lot of time to open the product package. | 0.922 | 0.955 | 0.877 | 0.936 |

| GP2: You consider that the product has excessive packaging. | 0.960 ** | ||||

| GP3: You consider that the product has lots of unnecessary packaging. | 0.927 ** | ||||

| Green brand attitude (Batra and Stamen [93]; Baumgarth [94]; Li et al. [95]) | GA1: You prefer the brand because it is environmentally friendly. | 0.928 | 0.946 | 0.856 | 0.925 |

| GA2: You favor the brand because of its environmental concerns. | 0.906 ** | ||||

| GA3: You think the brand is valuable because of its environmental performance. | 0.941 ** | ||||

| Green brand image (Chen [52]; Cretu and Brodie [64]; Padgett and Allen [96]) | GI1: The brand is considered as the benchmark of environmental commitment. | 0.841 | 0.940 | 0.760 | 0.872 |

| GI2: The brand’s environmental reputation is outstanding. | 0.910 ** | ||||

| GI3: The brand’s environmental performance is successful. | 0.902 ** | ||||

| GI4: The branding is based on its emphasis on environmental protection. | 0.834 ** | ||||

| GI5: The brand’s environmental commitment is trustworthy. | 0.868 ** | ||||

| Green brand attachment (Park et al. [57]; Thomson et al. [97]) | GT1: The brand’s eco-friendliness makes you feel strongly passionate about it. | 0.889 | 0.894 | 0.682 | 0.826 |

| GT2: The brand’s environmental concern makes you feel strongly passionate about it. | 0.868 ** | ||||

| GT3: The brand’s environmental performance makes you crave for it. | 0.792 ** | ||||

| GT4: The brand’s extraordinary environmental features make you willing to pay for it. | 0.745 ** |

| Constructs | Mean | Standard Deviation | A | B | C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Excessive product packaging | 2.97 | 1.50 | |||

| B. Green brand attitude | 5.43 | 1.02 | −0.247 ** | ||

| C. Green brand image | 5.11 | 1.01 | −0.169 ** | 0.735 ** | |

| D. Green brand attachment | 4.97 | 1.06 | −0.07 | 0.642 ** | 0.695 ** |

| Hypothesis | Proposed Effect | Path Coefficient | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | − | −0.251 *** | H1 is supported |

| H2 | − | −0.180 ** | H2 is supported |

| H3 | + | 0.408 *** | H3 is supported |

| H4 | + | 0.620 *** | H4 is supported |

| H5 | + | 0.109 | H5 is not supported |

| Model | χ² | df | ∆χ² | ∆df | GFI | AGFI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Path 1: “EP→GA→GB” | ||||||||

| 1. Partial mediation model | 283.069 | 69 | - | - | 0.884 | 0.824 | 0.934 | 0.114 |

| 2. Direct model | 296.927 | 70 | 13.858 | 1 | 0.880 | 0.821 | 0.930 | 0.117 |

| 3. Complete mediation model | 286.486 | 70 | 3.417 | 1 | 0.882 | 0.824 | 0.933 | 0.114 |

| Path 2: “EP→GI→GB” | ||||||||

| 1. Partial mediation model | 283.069 | 69 | - | - | 0.884 | 0.824 | 0.934 | 0.114 |

| 2. Direct model | 290.025 | 70 | 6.956 | 1 | 0.883 | 0.824 | 0.932 | 0.115 |

| 3. Complete mediation model | 286.486 | 70 | 3.417 | 1 | 0.882 | 0.824 | 0.933 | 0.114 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Y.-S.; Hung, S.-T.; Wang, T.-Y.; Huang, A.-F.; Liao, Y.-W. The Influence of Excessive Product Packaging on Green Brand Attachment: The Mediation Roles of Green Brand Attitude and Green Brand Image. Sustainability 2017, 9, 654. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9040654

Chen Y-S, Hung S-T, Wang T-Y, Huang A-F, Liao Y-W. The Influence of Excessive Product Packaging on Green Brand Attachment: The Mediation Roles of Green Brand Attitude and Green Brand Image. Sustainability. 2017; 9(4):654. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9040654

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Yu-Shan, Shu-Tzu Hung, Ting-Yu Wang, A-Fen Huang, and Yen-Wen Liao. 2017. "The Influence of Excessive Product Packaging on Green Brand Attachment: The Mediation Roles of Green Brand Attitude and Green Brand Image" Sustainability 9, no. 4: 654. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9040654

APA StyleChen, Y.-S., Hung, S.-T., Wang, T.-Y., Huang, A.-F., & Liao, Y.-W. (2017). The Influence of Excessive Product Packaging on Green Brand Attachment: The Mediation Roles of Green Brand Attitude and Green Brand Image. Sustainability, 9(4), 654. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9040654