Conflicts of Interest and Change in Original Intent: A Case Study of Vacant and Abandoned Homes Repurposed as Community Gardens in a Shrinking City, Daegu, South Korea

Abstract

:1. Introduction

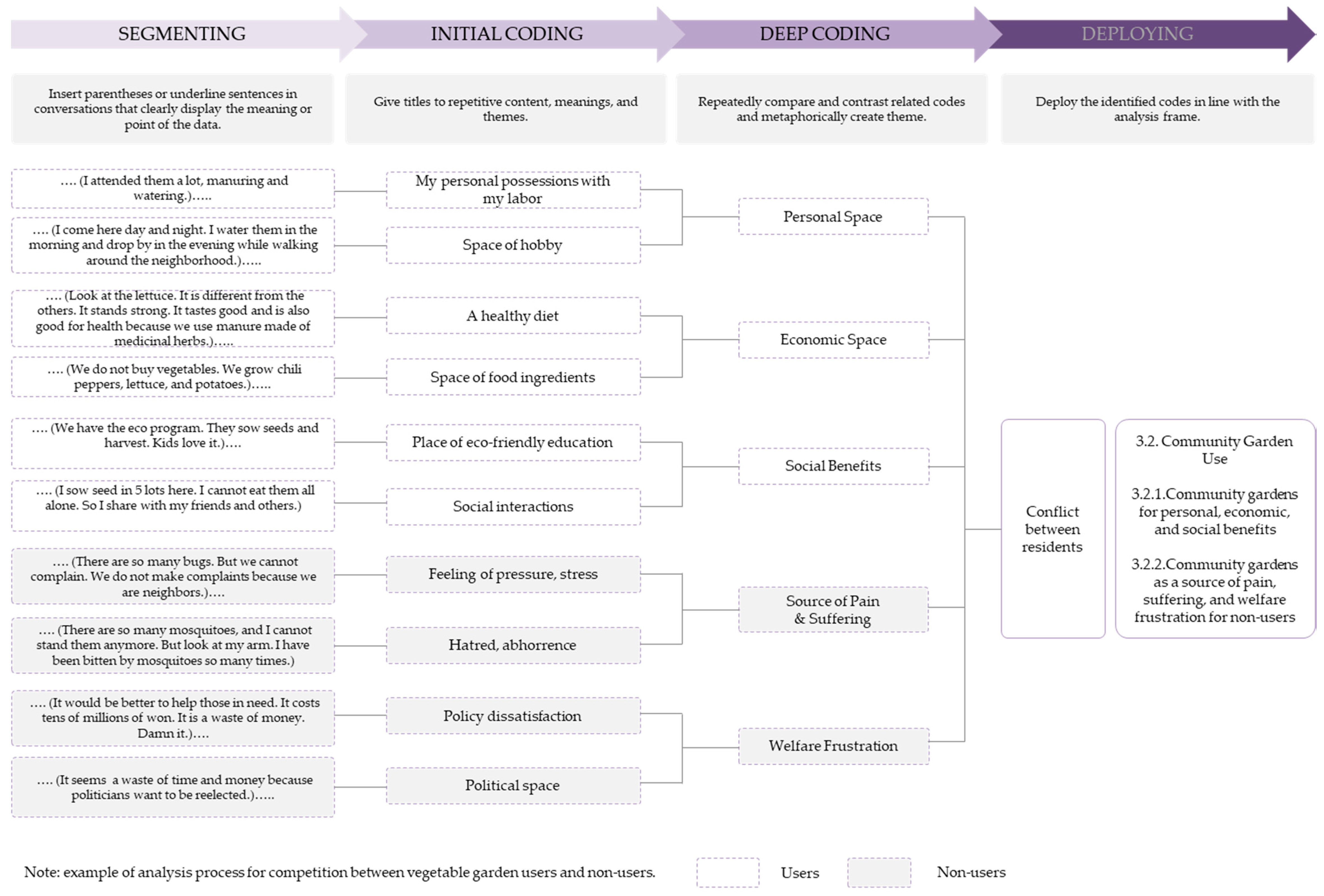

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Creating Community Gardens: Conflicts between Private and Public Parties

3.1.1. Beginning to Create a Community Garden Together

3.1.2. Emerging Discord: “Unequal Relationship”, “Exclusivity”, and “Withdrawal”

Now there is “my” garden and “your” garden in that small town, which creates a rivalry. Why? It must be due to pressure to perform. They took the credit for what we created, too. What’s the point of all this? The garden belongs to the town community. (N1)Whenever a newspaper reporter or other such people visited to interview us…the community service center complained that we were making it sound like we did it [created the garden] by ourselves when, according to them, they did it. And then later we found out in newspaper articles that they had taken credit for our garden as well. (N2)In the end, the NPO to which N1 and N2 belonged withdrew from the project, convinced it was being “excluded”. Currently, the project is being implemented as a residential urban beautification initiative, led by the municipal authority and funded by the city and the county.The presence of abandoned and dilapidated houses makes the neighbors very uncomfortable. They stink in the summer, which poses a public health concern. Besides, they are such an eyesore. (O1)Abandoned and dilapidated houses attract crime, so the primary goal is to demolish those structures. (O2)There are so many vacant and abandoned properties with dead tree leaves in and around them, which poses a fire hazard. And there’s the matter of potential collapse. (O3)

3.2. Community Garden Use: Conflict between Residents

3.2.1. Community Gardens for Personal, Economic, and Social Benefits

I garden, and then I bring some of my harvest to my son’s…and I also share it with my friends. I just pull it out and bring it to my friends [laughs]. Look at the lettuce. It is different from what you buy at the store. You have no idea how popular it is.… Everyone wants some. (RU1)

3.2.2. Community Gardens as a Source of Pain, Suffering, and Welfare Frustration for Non-Users

It’s no use studying stuff like this. It just sours relationships between neighbors. All this bickering and arguing…for what? In the end, only those who eat, get to eat, and those who don’t, don’t get to eat. It’s not even done together. Of course it makes you upset, if you are not picked to participate. (RN1)Some have up to five plots. You pick and see, and I pick and see. Somehow, they all pick. Even people who don’t live here sneak in to pick. Like this. It’s not right, correct? People shouldn’t do that, right? They all put dibs on it in the beginning, and then.… It makes me angry. (RN3)The hardship stemming from the community garden sometimes led to estranged family relationships and discontent with national welfare policies. RN2 was upset because RN2’s grandson would not visit for fear of the insects propagated by the community garden. RN3 and RN1 expressed dissatisfaction toward the garden and the welfare policy, while focusing on the fact that it was a public good funded by taxpayers.My grandson refuses to come visit his grandma because of the mosquitoes. He’s ten. I ask him to come for a visit, and he won’t, saying that there are too many mosquitoes in my place. Those who haven’t experienced it don’t understand. (RN2)Because it would cost money, the district office demolished it for free and told the neighborhood to utilize it.… Those who didn’t give permission received all sorts of crap. With what money did the district office do it? It just drives up our health insurance. Why don’t they help out those in need instead? Several tens of millions of won got poured into that. (RN3)There’s no welfare that doesn’t require tax money. The current state of the nation.… Young people are struggling to stay alive because of taxes.… Do they have money to burn? [profanity]. There’s no money to spend like this.… Tell them to find jobs for our unemployed youths instead. They are foaming at the mouth to score some easy points for the next election season. (RN1)

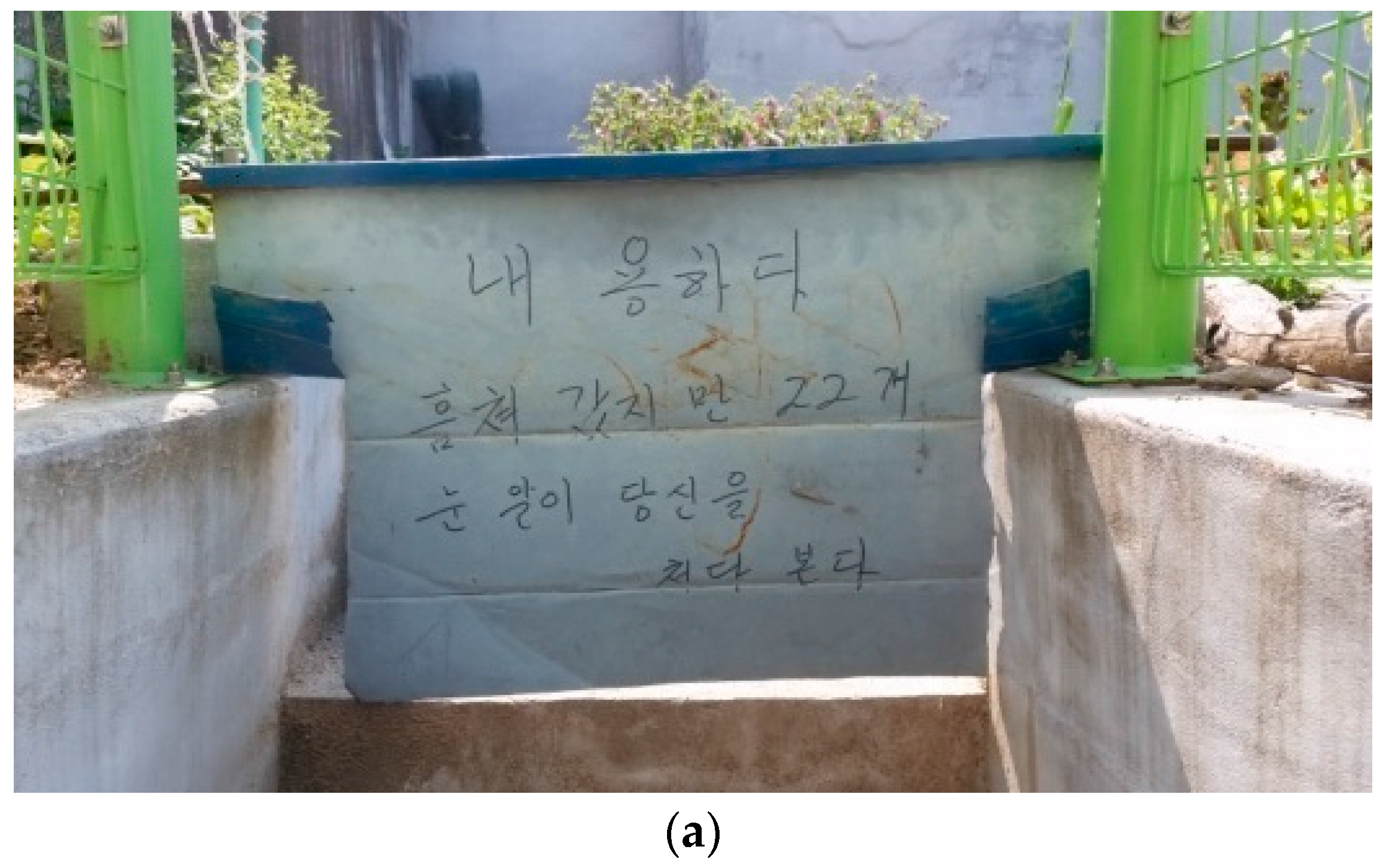

3.2.3. The Meaning of “Trees” and “Fences”: A Place of Rivalry and Exclusivity

Dude, this place is teeming with flies and mosquitos. They are watered. Sprayed. We have been living with the doors closed for two years now. Look at the water there. Look at the container (Figure 5). You see it’s swarming with bugs. But I can’t bring myself to talk to them about it. Because we are neighbors, I just keep quiet. And it turns out that from here to over there is my property. I wasn’t aware of it before the demolition [of the abandoned house].… So my son told me to plant some trees.… Plant some trees because we will get it [our property] back soon. (RN2)

It was not stealing.… So what if the neighborhood tore off and ate some vegetables? All the ladies do it at times as they hang out here and talk. Isn’t it understandable? I say people are so devoid of warmth. Look at the metal fencing.… Hell is raised if stuff goes missing. (RN2)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

- Interview questions

- To community members:

- Before the creation: What was this space like before, when it contained a vacant house?

- Composition process: What was the plot allotment process like following demolition?

- After the creation: How does one get to use the garden?

- What are the pros and cons of the garden?

- To government workers:

- Motive and goal of the project: How did the project come to be launched?

- What is the project’s goal?

- Process of creation: Did it incorporate the community members’ opinions?

- After the creation: How is the established garden managed?

- To non-profit members:

- Motive and goal of the project: How did the project come to be launched?

- What is the project’s goal?

- Process of creation: What are the events that unfolded during the creation process?

- After of creation: How did your level of involvement change after the garden was created?

References

- Oswalt, P.; Rieniets, T. Global Context. Shrinking Cities. 2007. Available online: http://www.shrinkingcities.com/globaler_kontext.0.html?&L=1 (accessed on 7 November 2017).

- Newman, G.D.; Bowman, A.O.; Lee, R.J.; Kim, B. A current inventory of vacant urban land in America. J. Urban Des. 2016, 21, 302–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Nasser, H. As Older Cities Shrink, Some Reinvent Themselves. USA Today. 27 December 2006. Available online: https://usatoday30.usatoday.com/news/nation/2006-12-26-shrinking-cities-cover_x.htm (accessed on 16 November 2017).

- Lanks, B. Creative Shrinkage. The New York Times Magazine. 10 December 2006. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/10/magazine/10section1B.t-3.html (accessed on 16 November 2017).

- Bontje, M. Facing the challenge of shrinking cities in East Germany: The case of Leipzig. GeoJournal 2005, 61, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauregard, R. Shrinking cities in the United States in historical perspective: A research note. In Proceedings of the Future of Shrinking Cities: Problems, Patterns and Strategies of Urban Transformation in a Global Context. Available online: http://www.rop.tu-dortmund.de/cms/Medienpool/Downloads/The_Future_of_Shrinking_MG-2009-01.pdf (accessed on 7 November 2017).

- Lee, H.; Han, S. Where Do Shrinking Cities Go From Here? Korea Research Institute for Human Settlements: Yanyang, Korea, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, Y.; Kim, S. The causes and characteristics of housing abandonment in an inner-city neighborhood—Focused on the Sungui-dong area, Nam-gu, Incheon. J. Urban Des. Inst. Korea Urban Des. 2016, 17, 83–100. [Google Scholar]

- Seoul National University R&DB Research Foundation. Data Collection on Current Condition of Urban Decay and Comprehensive Information System Development; Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport, the Korea Agency for Infrastructure Technology Advancement, and the Korea Urban Renaissance Center: Seoul, Korea, 2010.

- Spelman, W. Abandoned buildings: Magnets for crime? J. Crim. Justice 1993, 21, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stucky, T.D.; Ottensmann, J.R. Land use and violent crime? Criminology 2009, 47, 1223–1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Accordino, J.; Johnson, G.T. Addressing the vacant and abandoned property problem. J. Urban Aff. 2000, 22, 301–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.S. The impact of abandoned properties on nearby property values. Hous. Policy Debate 2014, 24, 311–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, I.; Weiland, U. Urban Gardening in Leipzig and Lisbon: A Comparative Study on Governance; COST (European Cooperation in Science and Technology): Leipzig, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Rall, E.L.; Haase, D. Creative intervention in a dynamic city: A sustainability assessment of an interim use strategy for brownfields in Leipzig, Germany. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 100, 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ha, C.; Kwak, H.; Kim, H. A study on utilization and making vegetable garden of vacant land and deserted house in deteriorated low-rise residential area for neighborhood regeneration—Focused on no-song low-rise residence district in Jeonju. J. Urban Des. Inst. Korea Urban Des. 2013, 14, 81–93. [Google Scholar]

- An, H.; Park, H. Flexible urban regeneration: Creative use of empty houses and vacant plots—Focused on temporary uses and tactical urbanism. J. Korea Plan. Assoc. 2013, 48, 347–366. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.Y.; Lee, Y.S. A study on design direction of community garden in urban deprived area through analysis of psychological and social effects-Targeting on the community garden of Jeonju-si urban regeneration test-bed area. Des. Converg. Study 2013, 12, 83–98. [Google Scholar]

- Samsung Economic Research Institute. Secret of Rival City, Urban Regeneration. SERI Kyoung-Young Note. 2012. Available online: https://www.google.co.kr/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=2&ved=0ahUKEwjV04qekcPXAhVCUrwKHarjBgIQFggoMAE&url=http%3A%2F%2Fmaljong.tistory.com%2Fattachment%2Fcfile27.uf%40230B803D52DE175F0C4781.pdf&usg=AOvVaw1Xl-vaKCBLHrytH8jd0vah (accessed on 9 November 2017).

- Bishop, P.; Williams, L. The Temporary City; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, J.H. Resolving environmental conflicts in Korea: Issues and solutions. Environ. Law Rev. 2010, 32, 385–416. [Google Scholar]

- Franks, D.M.; Davis, R.; Bebbington, A.J.; Ali, S.H.; Kemp, D.; Scurrah, M. Conflict translates environmental and social risk into business costs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 7576–7581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cho, M.R. Causes and structure of environmental conflicts concerning national development projects. ECO Korea Assoc. Environ. Soc. 2003, 12, 110–146. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbitt, K.; Jones, P.; Meegan, R. Tackling social exclusion: The role of social capital in urban regeneration on Merseyside: From mistrust to trust? Eur. Plan. Stud. 2001, 9, 141–161. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.W.; Song, T. A conflict minimization scheme in urban regeneration projects. Korea Policy Stud. 2013, 13, 133–148. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam, R.D.; Leonardi, R.; Nanetti, R.Y. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2025 Daegu Metropolitan City Urban Regeneration Strategic Plan. Daegu Metropolitan City. 2016. Available online: http://www.daegu.go.kr/cmsh/daegu.go.kr/build/file/2025Urban_renewal_report.pdf (accessed on 5 November 2017).

- Daegu Metropolitan City. Available online: http://info.daegu.go.kr/newshome/mtnmain.php?mtnkey=articleview&mkey=scatelist&mkey2=26&aid=185036 (accessed on 1 October 2017).

- The Hankyoreh. Available online: http://www.hani.co.kr/arti/economy/economy_general/608054.html (accessed on 1 October 2017).

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 2nd ed.; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S.B. Qualitative Research and Case Study Application in Education; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Punch, K. Introduction to Social Research: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches; Sage: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B.G.; Strauss, A.L. The Discovery of Grounded Theory; Aldine: Chicago, IL, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, O.J.; Schoepfle, G.M. Systematic Fieldwork: Ethnographic Analysis and Data Management; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1987; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Saito, J. Publicness; Iwanami Shoten: Tokyo, Japan, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Holcombe, R.G. Public Sector Economics: The Role of Government in the American Economy; Pearson Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Hardin, G. The tragedy of the commons. Science 1968, 162, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobbes, T. Leviathan; A & C Black: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, C. The comedy of the commons: Custom, commerce, and inherently public property. Univ. Chic. Law Rev. 1986, 53, 711–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. Crafting Institutions for Self-Governing Irrigation Systems; ICS Press: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstadt, S.N.; Roniger, L. Patrons, Clients and Friends: Interpersonal Relations and the Structure of Trust in Society; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1984; pp. 48–49. [Google Scholar]

- Drake, L.; Lawson, L.J. Validating verdancy or vacancy? The relationship of community gardens and vacant lands in the US. Cities 2014, 40, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, L.J. City Bountiful: A Century of Community Gardening in America; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey, N.; Burton, M. Defining place-keeping: The long-term management of public spaces. Urban For. Urban Green. 2012, 11, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayhew, M.G.; Ashkanasy, N.M.; Bramble, T.; Gardner, J. A study of the antecedents and consequences of psychological ownership in organizational settings. J. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 147, 477–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Current Usage Status | No./Code | Gender | Age Group | Location Residence | Years of Residence | Years of Use |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Users | RU1 | F | mid-60s | nearby | 25 | 3 |

| RU2 | F | late 20s | other neighborhood | 3 | 3 | |

| RU3 | M | late 60s | nearby | 30 | 3 | |

| RU4 | M | mid-70s | nearby | 40 | 3 | |

| Non-users | RN1 | F | early 70s | nearby | 30 | 0 |

| RN2 | F | early 70s | nearby | 40 | Less than 1 | |

| RN3 | F | mid-70s | nearby | 30 | 0 |

| Category | No./Code | Gender | Age Group | Educational Attainment | Years of Employment in Relevant Dept. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Government workers | O1 | M | late 50s | College degree | Over 10 |

| O2 | M | early 50s | College degree | 5 | |

| O3 | M | mid-40s | College degree | 1 |

| Category | No./Code | Gender | Age Group | Educational Level | Years of Working, Employment, or Membership |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-profit members | N1 | M | mi-40s | College degree | 8 |

| N2 | M | early 30s | College degree | 4 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, J.-W.; Sung, J.-S. Conflicts of Interest and Change in Original Intent: A Case Study of Vacant and Abandoned Homes Repurposed as Community Gardens in a Shrinking City, Daegu, South Korea. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2140. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9112140

Lee J-W, Sung J-S. Conflicts of Interest and Change in Original Intent: A Case Study of Vacant and Abandoned Homes Repurposed as Community Gardens in a Shrinking City, Daegu, South Korea. Sustainability. 2017; 9(11):2140. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9112140

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Jin-Wook, and Jong-Sang Sung. 2017. "Conflicts of Interest and Change in Original Intent: A Case Study of Vacant and Abandoned Homes Repurposed as Community Gardens in a Shrinking City, Daegu, South Korea" Sustainability 9, no. 11: 2140. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9112140