4.2. Rural Land Reform and CURD in Chengdu

From 2003 to 2007, the Chengdu government invested a huge amount of capital into relocating farmers to urban areas, albeit without much success. In 2008, the government implemented a policy to accelerate the urbanisation process and reduce the gap between urban and rural citizens by reforming the rural land system, with a focus on the registration and confirmation of rural land rights and the circulation of rural land in the open market. Under the guidance of that policy, the Chengdu government has carried out experiments of rural land property rights reform in Dujiangyan, Wenjiang, Shuangliu, Dayi and 14 other counties. The foundation of that reform is the registration and confirmation of rural land and property ownership, with farmers issued certificates giving them the right to carry out the contracted management of their rural land. Then, based on the registration and confirmation of rural land and property ownership, that land can be circulated in the open market effectively and efficiently. With the success of these trials, CURD in Chengdu currently covers all rural prefectures, including both the sub-urban and remote ones.

With regard to rural collective land and property, farmers can operate rural tourism businesses or engage in other types of commercial activities themselves or lease their land to rural collective economic organisations and work for them to obtain both leasing and employment income [

25]. Such a scheme was first experimented with in Longhua Village and Sansheng Village. With regard to rural farmland, farmers can transfer the management rights to their farmland to rural enterprises or rural collective economic organisations, which in turn manage and operate that land, or they can subcontract or lease it to a commercial operator for better land use, thereby increasing farmers’ income from land circulation and from working. By the end of 2014, 2308 million km

2 of rural cultivated land was in circulation and 54.1% of farmland was being used in one of the aforementioned ways.

In the past decade of CURD strategic development, farmers’ quality of life has improved significantly. For example, in Shuangliu Prefecture, the local government has constructed residential districts for rural farmers that provide a better housing environment and more facilities than what they had previously and have achieved the effective and intensive use of rural housing land. Rural residents’ annual total per capita income increased from RMB ¥5252.76 in 2003 to RMB ¥7752.80 in 2007 and to RMB ¥16,806.29 in 2013 (In 2003, the exchange rate between US dollars and RMB yuan was 1:8.27. In 2007, it was 1:7.6. In 2013, the exchange rate dropped to 1:6.19.). The gap in annual income between urban and rural residents has also narrowed from 2.28:1 in 2003 to 2.06:1 in 2007 and to 1.93:1 in 2013. The education level of rural citizens, too, has undergone obvious enhancement, with the proportion of those obtaining at least a junior high school diploma increasing from 70.3% in 2003 to 78.75% in 2013.

In 2003, Chengdu started to implement reform policies targeting more efficient rural land use under the general guidelines of the CURD strategy. The Chengdu government issues certificates of usage rights to rural land to each rural inhabitant certifying that they hold the right to use, transfer and enjoy income from that land. This is the so-called land titling policy. Since 2008, land titling has been implemented in such a way that land titles are assigned back to rural villagers to effectuate transfers after a government survey was conducted to delineate boundaries. In March 2008, the first land title was issued in Heming Village. It is not surprising that disputes have arisen over the boundary delineation. The Chengdu authorities have resorted to negotiation via village council meetings in which villagers discuss various issues of concern and resolve differences concerning boundary delineation before official recognition by the government. By the end of 2010, land ownership titles had been assigned to more than 33,800 rural collectives. Almost 1.8 million households obtained new titles to their agricultural land under the Household Responsibility System. In addition, 1.66 million households received titles to construction land classified as either “housing land” or “other types of rural construction land.” Land titling now covers most rural areas in Chengdu.

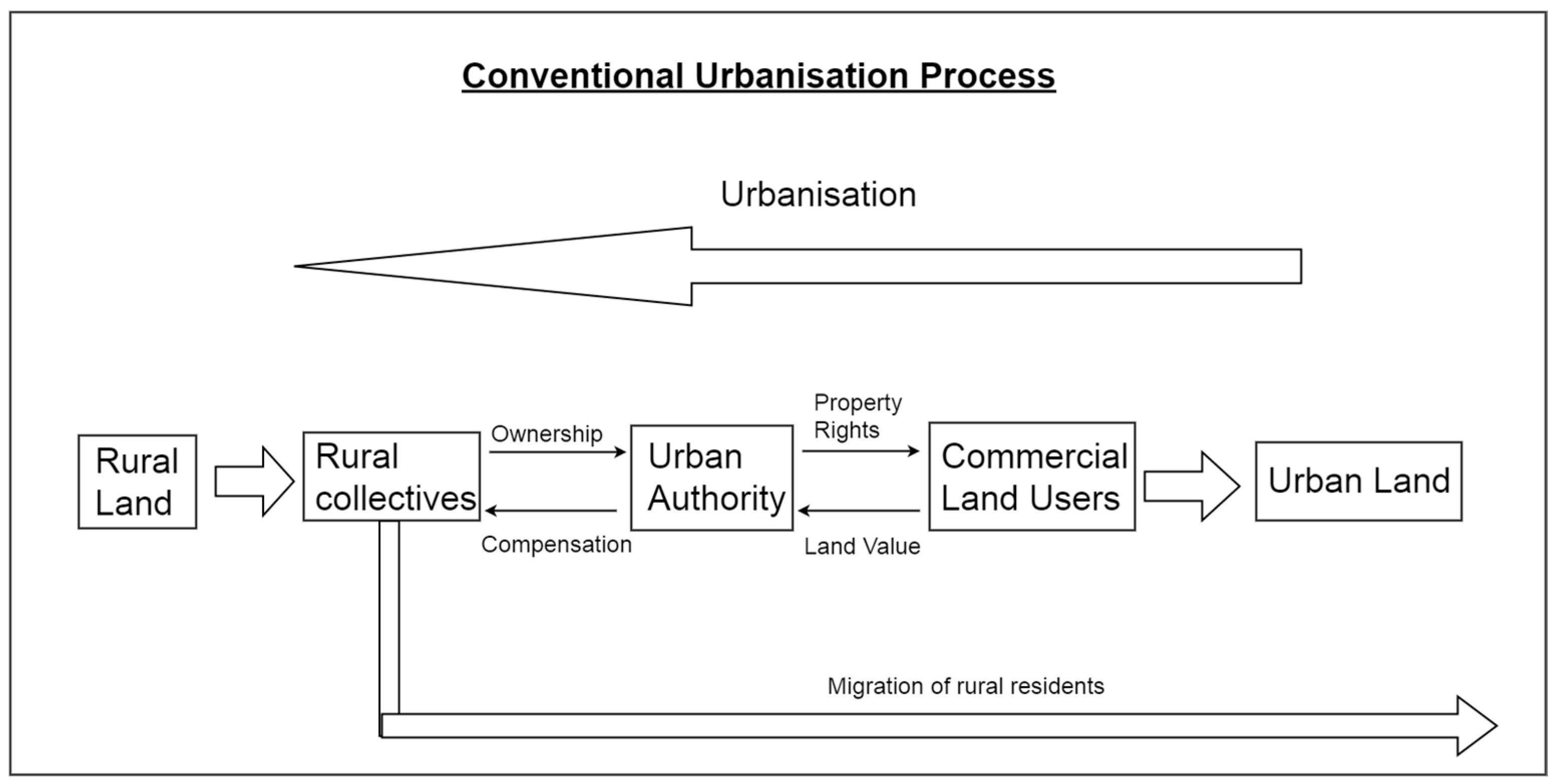

To conceptualise such policy change brought about by the CURD ideology, the following two models are illustrated.

Figure 1 shows the conventional urbanization model when rural/agricultural land is being encroached. In

Figure 1, we can see that under conventional urbanization process, urban boundary is being pushed outwards, encroaching rural land due to development pressure. In this process, commercial land users, usually the real estate developers, are the main actors in converting rural land into urbanized commercial land either for residential, resort or business-oriented purposes. This conversion is physical and one way, meaning existing rural owners of such land are compensated one way or the other and displaced from the ownership as well as the use of such land afterwards. Land in rural China broadly belongs to village collectives, which have three major categories of stakeholders in the governance arrangement, namely township, villages and villagers. There is no express stipulation on how to allocate the property rights to each of these stakeholders by law. Rural residents lack the legal title to dispose land. The rights to dispose land is the core of all property rights and a significant indicator of an efficient circulation system for land in the rural areas. Farmers are prohibited from transferring rural land owned collectively by law, and they only have the rights of disposal through village collectives. A direct consequence of this is rural-to-urban migration of these rural residents, as the loss of rural land deprives these rural residents from their basic tool of production. However, due to the problem of the urban household registration system, these rural migrants cannot enjoy the same level of social benefits their urban counterparts have in the city. Under such urbanization process, rural residents receive double penalty in terms of welfare and therefore become the main victim in China. The issue therefore hinges on solving the obscured property rights over rural land and the status of household registration. On the other hand, from land administration’s point of view, this conventional model also produces some problems. First of all, because the local government is the only entity to convert rural land, it increases unnecessary conflict and negotiation between the authority and rural farmers over compensation and re-settlement issues [

16]. On the other hand, because of the potential financial gains in this process, it also opens up opportunity for corruption. The advent of the CURD ideology targets these problems with a core element of granting land title back to the individual rural owners.

Under the CURD ideology, it is hoped that the following socio-economic benefits can be brought to the rural residents:

- -

To improve economic gains for the rural residents in combined ways, including rental income of the long lease on their own farmland (or in cases where the rural residents decide to sell, capital value); dividends on the economic return to be generated on their land and formal salaries for working on the new enterprise is to be setup on their land;

- -

To allow technical and knowledge transfer for the rural residents once they are employed as part-owner and part-worker by the new enterprises. This enables them to learn commercial skills to continue with the viable business on their site once the long lease expires;

- -

To allow for formal social insurance and security packages to be offered to the rural residents once they are formally employed by a business enterprise;

- -

To provide urban Hukou (household registration) to the rural residents once they join the CURD package, and this entitles them to such urban benefits as medical and education;

- -

To enhance personal satisfaction and self-esteem of the rural residents when their living standard is being raised.

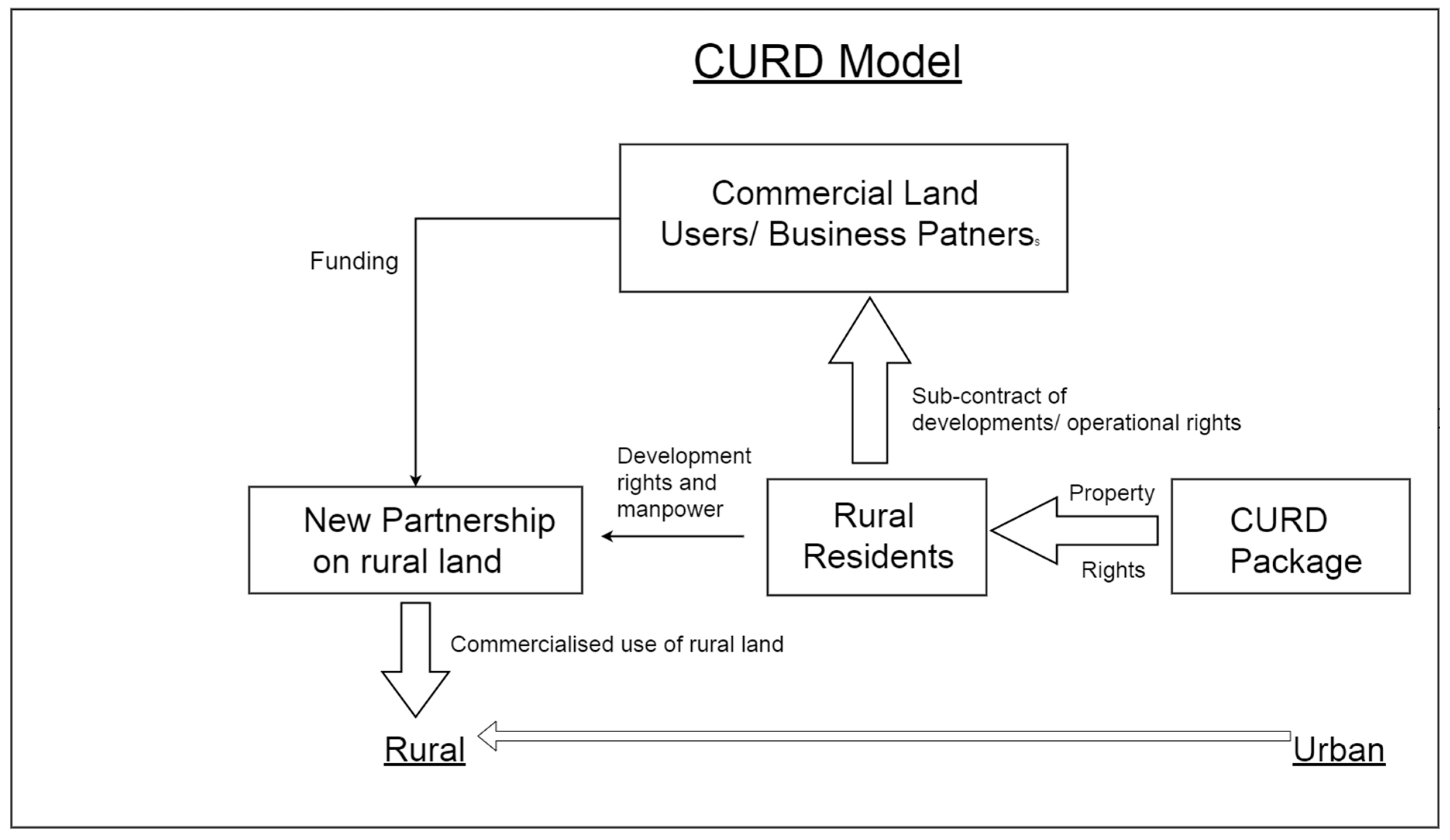

Figure 2 illustrates this transformation under the CURD ideology. As mentioned above, the ideology of CURD evolves around improving the three core issues in the rural areas, which eventually aim at alleviating the livelihood of rural residents in China. Since the farmers in the rural collectives are living in a closely knit community, issuance of property rights certificates was completed within a short period of time and in an efficient manner that allowed the rural farmers to experiment other alternative use of their land without major problems. In terms of governance of the land tenure system, the CURD policies allowed for a smooth transition to convert rural land into more commercial use without the hassles of land requisition and compensation negotiation. This also minimised political risk for the local authority. Property rights on rural land are now more clearly defined and transferrable that makes circulation of surplus rural land into commercial use feasible. In the end, rural farmers are able to utilise their surplus farmland as a means for wealth accumulation in a similar manner as their urban counterparts. From the figure, we can see that the CURD ideology aims at facilitating a more sustainable urbanisation process that will raise the living standard and welfare state of the rural residents by giving them full legal title on land, which they can utilise as capital to accommodate economic expansion of urban activities.

These benefits are to be delivered via the following policy/operational principles:

No land requisition and no compulsory purchase of land to be initiated; apply the core principle of “Farmers leave their land without leaving their village (li tu bu li xiang)”;

Using commercial enterprises to support rural economy;

Rural farmers enjoy equal social benefits as their urban counterparts.

With the implementation of CURD policies, rural residents were given the property rights certificate on their farmland as elaborated above. To accelerate urbanisation and the relocation of rural villagers, the Chengdu government reorganises rural land (mainly building land) and issues certificates of ownership and usage rights for collective land and property and offers subsidies to these rural residents in the countryside to construct housing villages with higher intensity and concentration of residents. In this way, physical and social infrastructure can be provided by the government to these residents in a more efficient way in the rural areas. Upon receiving the property rights on their land, rural residents can operate tourist-oriented businesses or other types of commercial activity such as commercial gardens/fruit farms (nongjiale) for urban residents in joint venture with business entities which provide funding and management expertise in return for a management lease on the land. Trial farms have been established in Longhua Village and Sansheng Village. Alternatively, rural villagers can choose to live in urban areas and enjoy the same rights and social welfare as other urban citizens by voluntarily giving up both management rights to rural land and usage rights to construction land. The rural land that is returned is managed by the city government and operated by rural collective economic organisations. An example can be found in Wenzhou, Chengdu.

To a very large extent, CURD policies help to improve the governance structure of the complicated rural land tenure system in China. The most significant result is the circulation of surplus rural land into more efficient commercial use without the unnecessary conflicts in the requisition process. While the local government may not have the access to the potential financial gains in the conversion process of rural land to urban construction land as they enjoyed in the past, they now find less political risks in developing rural areas for high-value commercial activities such as catering or tourism which will also eventually bring in tax income for them. More importantly, there is now less pressure in dealing with the influx of displaced rural farmers in the urban areas, which also alleviates such urban problems as crime and demand for welfare housing. On balance, local authorities find it a harmonious approach to sustain long-term economic growth for the whole district, and “harmony” is always a keyword for success as far as local governments are concerned.

With the property rights over their land being ascertained, most rural residents choose to sub-contract the use-rights of their land for commercial uses that cater to the socio-economic needs of their urban counterparts so that they would not need to leave their village and their own social network. This fulfills the operational principle of “li tu bu li xiang” described above. With the aim of intensifying the utilisation and operation of rural cultivated land, the Chengdu government has proposed that farmers be able to transfer management rights to contracted farmland to rural enterprises or rural collective economic organisations, which take responsibility for managing and operating them on a larger scale via subcontracting, leasing or demutualising, thereby boosting farmers’ income through land circulation and employment. Hence, instead of physically converting agricultural land into residential or commercial space, CURD allows the rural residents to be temporarily separated from the ownership of such land, which will then be leased to a commercial entity for such purposes as restaurant, resort or a hybrid of commercial farm and restaurant (i.e., nongjiale). These leases on the use of land (usually around 30 years) enable urban commercial entities to tap into rural resources without the need to take over their property rights on such assets and compensate them, especially land. In return, the rural land owners obtain rental income on their land, job opportunity with these new operators, management skills in running commercial entities on their own land, and an increase in welfare.

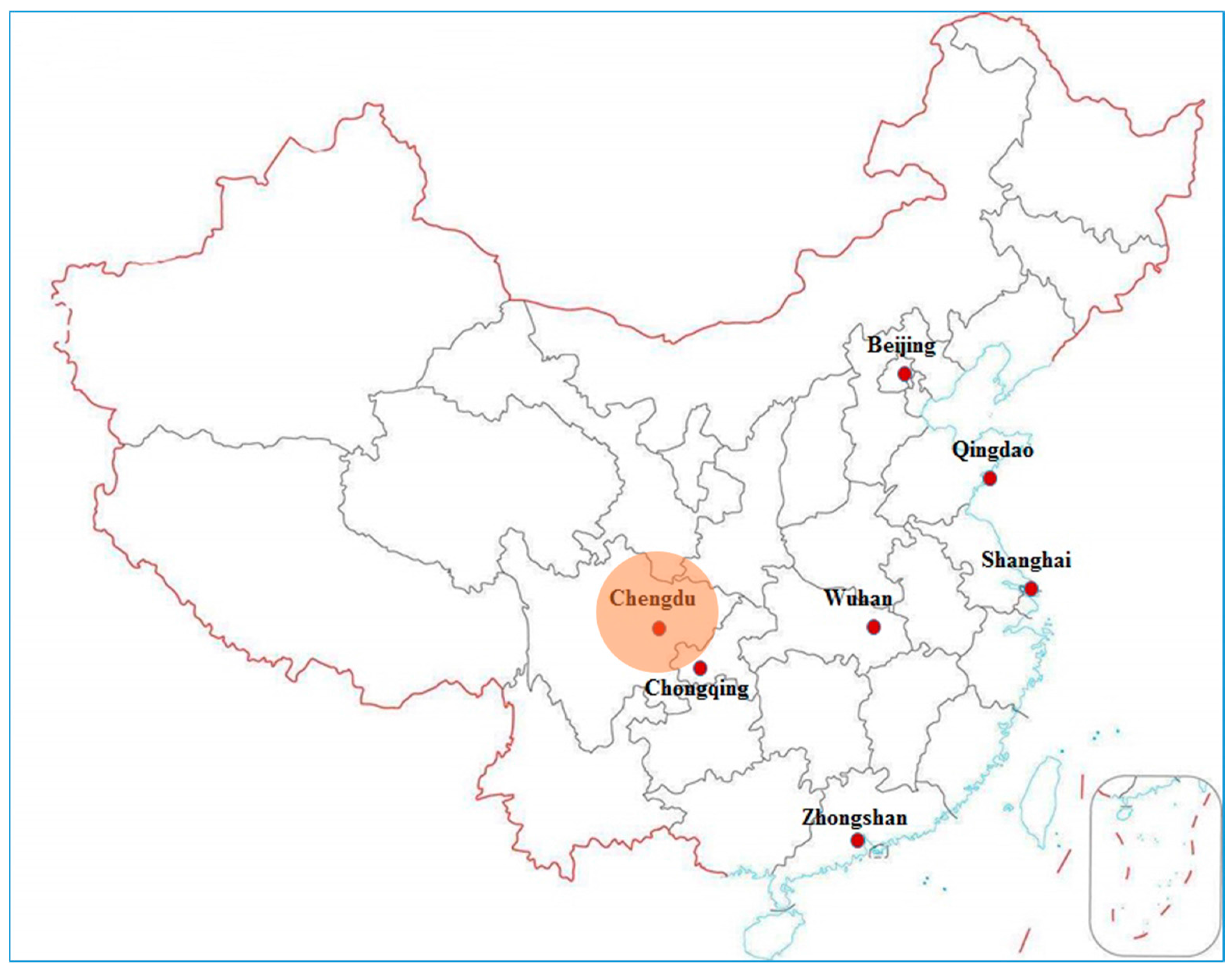

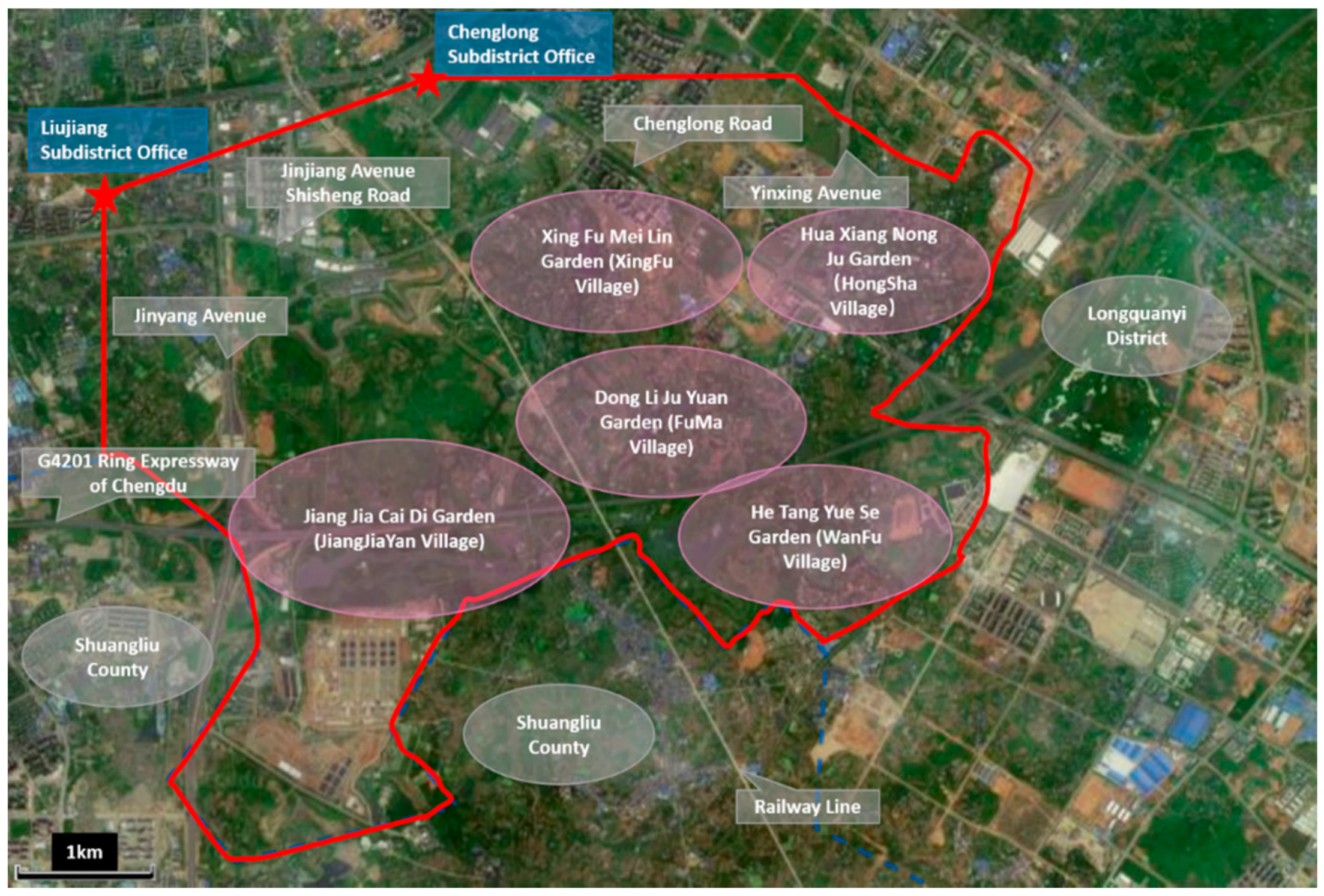

An example to illustrate this outcome is the Sansheng Flower Village development. Sansheng Flower Villages is a cluster of five villages in Jinjiang District of Chengdu, which is the northeastern part of Chengdu (

Figure 3 and

Figure 4). These five villages are Hongsha Village, Xinfu Village, Jiangjiayan Village, Fuma Village, and Wanfu Village (

Figure 5). The total area of this cluster is about 12 km

2. They are called flower villages because of a major flowers exhibition held in Hongsha village in 2003. Since then, the other villages took turn in organising this event, and eventually, this cluster of villages earned the title of Five Golden Flowers, and hence the name Sansheng Flower Villages. According to government record, by the end of 2013, there was a total rural population of 27,410 living in this cluster. Per capita annual income at that time was about 19,921 Yuan (almost a three-times increase from the year 2004 at 6080 Yuan).

From our survey on Sansheng Flower Villages, we notice that most of the original farmland in the complex has been turned into commercial operations of all sorts. Part of the farm plots have been converted into commercial farmland for selling indoor and outdoor plants for city dwellers. A significant part of the complex has also been turned into catering/resort/conference facilities (

Figure 6) that target various leisure and commercial activities extending from the urban centre. On the other hand, a not insignificant part of the Sansheng Flower village site remains as tranquil rural residential land occupied by these rural residents who either work on these converted commercial facilities or lease out their land to their urban partners (

Figure 7). Hence, it fits exactly the principle of “leaving the farmland without leaving the village”.

For the city government, this also allows a much more efficient and sustainable urbanisation process to be carried out, as rural residents who scattered around in the rural area in the past are now more centralised in the new developments. Urban residents can now also access sub-urban and even more remote rural land for social and economic activities.

Subsequent to the land titling initiative, six pertinent policy documents were issued by the local government. A “land for new housing” policy was established in 2008/2009 whereby rural homeowners who want to transfer their land first need to obtain titles for their housing land. Upon receipt of those titles, they are free to find an investor/financier to provide them the capital to build a new house elsewhere. As long as the land area occupied by their new house is smaller than that of their old housing land, as shown on the title, the housing land can be transferred to an investor for such “business” uses as tourist resorts and restaurants. The contract for such a transaction is signed not only by the original housing land owner and the investor, but also by the head of the collective, which is the land’s legal owner. This policy therefore bestowed transfer rights to rural construction land for the first time. Under its terms, investors who are not members of the respective rural collective or village can be granted land user rights for 40 or 50 years.

Generally speaking, the Sansheng Flower Village case shows that urbanisation comes to an amiable convergence with the rural area. The physical boundary between urban and rural still exists, but the functional boundary is being merged (

Figure 8).