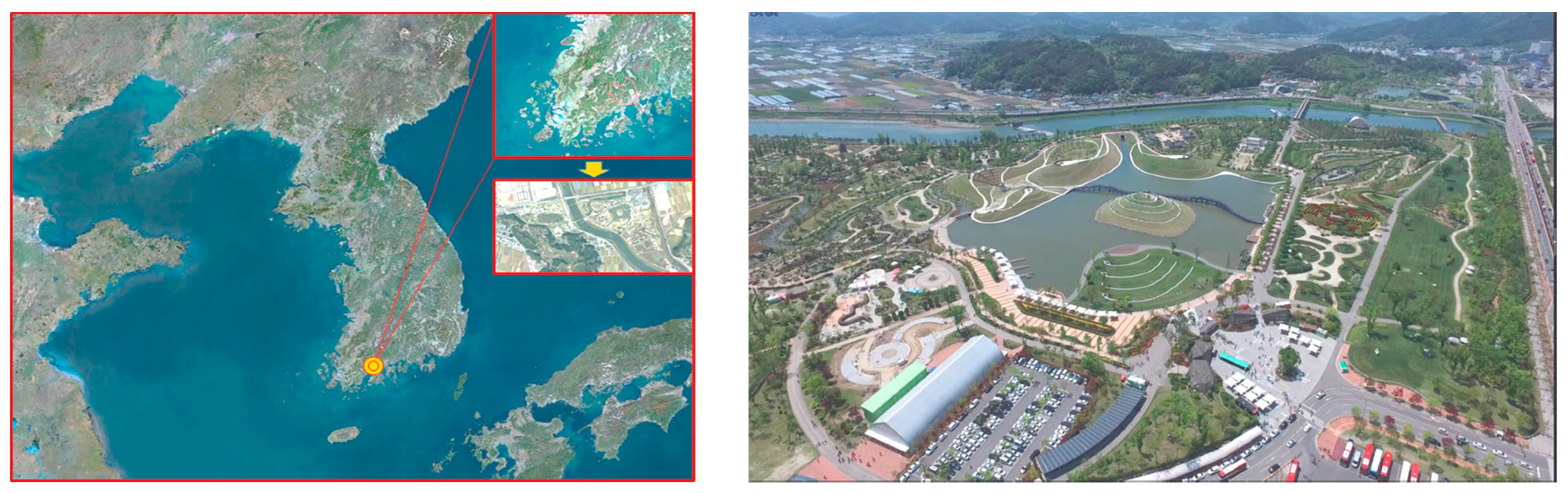

Perspectives on the Direction of the Suncheon Bay National Garden from Local Residents and Non-Local Visitors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Purpose of Research

1.2. Theoretical Considerations and Literature Review

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

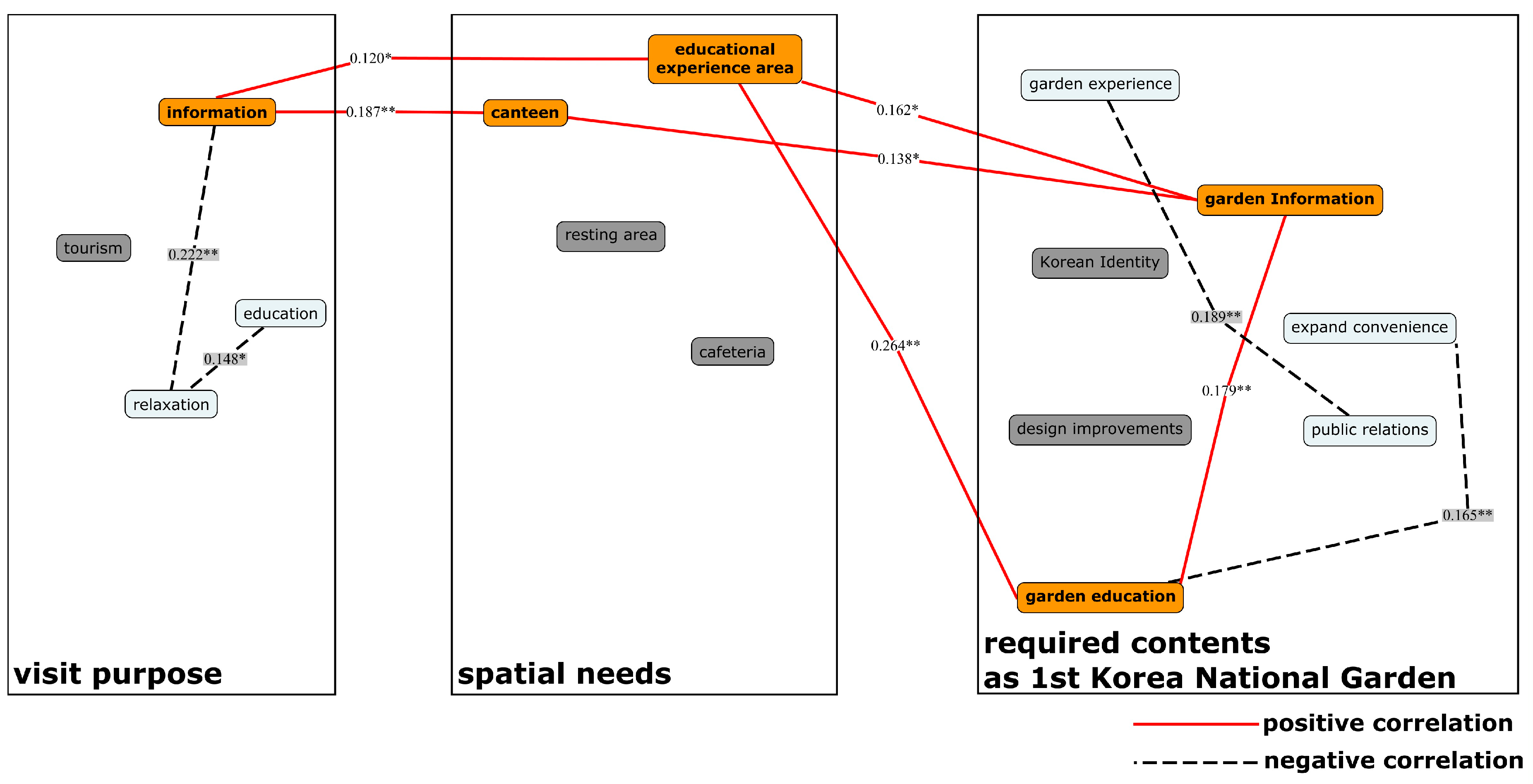

3.1. Non-Resident Visitors’ Concerns

3.2. Local Residents’ Concerns

3.3. Differences between Findings for Non-Residents and Local Residents

3.4. Common Data between Visitors and Locals

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- (i)

- What is the purpose of visiting this place? (information/tourism/education/relaxation)

- (ii)

- Which space is the most needed for the use of this place? (canteen/educational experience area/resting area/cafeteria)

- (iii)

- Which element is most vital for the first national garden? (garden experience/garden information/Korean identity/design improvement/expand convenience/public relations/garden education)

References

- National Law Information Center. Available online: http://www.law.go.kr/lsSc.do?menuId=0&subMenu=1&query=%EC%A0%95%EC%9B%90%EB%B2%95#undefined (accessed on 6 September 2017).

- Kim, B.M.; Song, K. The analysis on satisfaction and re-visiting factors in Suncheon Bay Garden Expo. Tour. Inst. Northeast Asia 2014, 24, 77–93. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, M.-J.; Choi, J.-M. The implication and recognition of International Garden Exposition Suncheon Bay Korea 2013 on Blogs. J. Korean Inst. Landsc. Archit. 2014, 42, 60–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.G.; Ahn, K.H.; Seo, S.C.; Kim, E.I. A study of future utilization and visitor perceptions of the Suncheon Bay International Garden Expo 2013. J. Recreat. Landsc. 2014, 8, 33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, L.R.; Long, P.T.; Perdue, R.R.; Kieselbach, S. The impact of tourism development on residents’ perceptions of community life. J. Travel Res. 1988, 27, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, K. Guidelines for socially appropriate tourism development in British Columbia. J. Travel Res. 1982, 21, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, D.; Allen, J.; Cosenza, R.M. Segmenting local residents by their attitudes, interests, and opinions toward tourism. J. Travel Res. 1988, 27, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.D.; Snepenger, D.J.; Akis, S. Residents’ perceptions of tourism development. Ann. Tour. Res. 1994, 21, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, H.C. Tourist Behavior; KNOU Press: Seoul, Korea, 2015; ISBN 9788920926037. [Google Scholar]

- Windsor Garden Castle. Available online: https://www.windsor.gov.uk (accessed on 9 September 2017).

- Shinjuku Gyoen National Garden. Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/garden/shinjukugyoen/english/1_intro/history.html (accessed on 9 September 2017).

- Benfield, R. 2013 Garden Tourism; CAB International: Boston, MA, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-78064-195-9. [Google Scholar]

- National Parks Board. Available online: https://www.nparks.gov.sg/news/2007/11/singapores-gardens-by-the-bay-project-on-track-with-groundbreaking-ceremony (accessed on 9 September 2017).

- Oxford English Dictionary. Available online: https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/ (accessed on 9 September 2017).

- Clifford, D. History of Garden Design, 2nd ed.; Faber & Faber: London, UK, 1966; ISBN 978-0-571-06810-4. [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach-Spriggs, N.; Kaufman, R.; Warner, S.B., Jr. Restorative Gardens: The Healing Landscape; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2004; ISBN 978-0-300-10710-4. [Google Scholar]

- Stigsdotter, U.; Grahn, P. What makes a garden a healing garden. J. Ther. Hortic. 2002, 13, 60–69. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, J.D. Greater Perfections: The Practice of Garden Theory; University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-8122-3506-7. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, J.S. Green-health topology. J. Environ. Stud. 2014, 53, 71–79. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, C.C. The garden as metaphor. In The Meaning of Gardens; Francis, M., Hester, R.T., Eds.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1992; pp. 26–33. ISBN 9780262061278. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, P.G. Design Thinking; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1991; ISBN 978-0-262-68067-7. [Google Scholar]

- Ballantyne, R.; Packer, J.; Hughes, K. Environmental awareness, interests and motives of botanic gardens visitors: Implications for interpretive practice. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 439–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunkoo, R.; Smith, S.L.; Ramkissoon, H. Residents’ attitudes to tourism: A longitudinal study of 140 articles from 1984 to 2010. J. Sustain. Tour. 2013, 21, 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, S. Information and empowerment: The keys to achieving sustainable tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 2006, 14, 629–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, S.; Nyaupane, G.P.; Budruk, M. Stakeholders’ perspectives of sustainable tourism development: A new approach to measuring outcomes. J. Travel Res. 2016, 55, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharana, I.; Rai, S.C.; Sharma, E. Valuing ecotourism in a sacred lake of the Sikkim Himalaya, India. Environ. Conserv. 2000, 27, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yacob, M.R.; Radam, A.; Shuib, A. A contingent valuation study of marine parks ecotourism: The case of Pulau Payar and Pulau Redang in Malaysia. J. Sustain. Dev. 2009, 2, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagles, P.F.; McCool, S.F. Tourism in National Parks and Protected Areas: Planning and Management; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2002; ISBN 0851995896. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, S.W. Tourism, national parks and sustainability. In Tourism and National Parks: Issues and Implications; Butler, R.W., Boyd, S.W., Eds.; Wiley: London, UK, 2000; pp. 161–186. ISBN 0471988944. [Google Scholar]

- Pigram, J.J.J.; Sundell, R.C. National Parks and Protected Areas: Selection, Delimitation, and Management; Centre for Water Policy Research, University of New England: Biddeford, ME, USA, 1997; ISBN 9781863894012. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, J.G.; Serafin, R. National Parks and Protected Areas: Keystones to Conservation and Sustainable Development; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013; p. 40. ISBN 978-3-642-60907-7. [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson, J.S. Botanic gardens science for conservation and global change. Trends Plant Sci. 2009, 14, 608–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, S.M. The role of Mediterranean botanic gardens in plant conservation. Webbia 1979, 34, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, S. Reconceptualising gardening to promote inclusive education for sustainable development. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2012, 16, 581–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergou, A.; Willison, J. Relating social inclusion and environmental issues in botanic gardens. Environ. Educ. Res. 2016, 22, 21–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutherland, L.A. Broadening the view of ecotourism: Botanic gardens in less developed countries. In Ecotourism and Environmental Sustainability: Principles and Practice; Hill, J., Gale, T., Eds.; Ashgate Publishing: Farnham, UK, 2009; pp. 197–222. ISBN 978-0-7546-7262-3. [Google Scholar]

- Boley, B.B.; McGehee, N.G.; Perdue, R.R.; Long, P. Empowerment and resident attitudes toward tourism: Strengthening the theoretical foundation through a Weberian lens. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 49, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USA EPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency). Available online: https://archive.epa.gov/ged/tutorial/web/html/index.html (accessed on 9 September 2017).

- Duran-Pinedo, A.E.; Paster, B.; Teles, R.; Frias-Lopez, J. Correlation network analysis applied to complex biofilm communities. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Horvath, S. A general framework for weighted gene co-expression network analysis. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2005, 4, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Non-Resident Visitors | Local Residents | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Correlation | ▲Information | — | ★Korean Identity | ▲Information | — | ◆Educational experience area |

| ▲Tourism | — | ★Korean Identity | ▲Information | — | ◆Cafeteria | |

| . | . | . | . | . | . | |

| . | . | . | ◆Educational experience area | — | ★Garden education | |

| . | . | . | ◆Educational experience area | — | ★Garden information | |

| . | . | . | ◆Cafeteria | — | ★Garden information | |

| ★Korean Identity | — | ★Design Improvement | . | . | . | |

| Negative Correlation | ▲Tourism | — | ▲Education | ▲Information | — | ▲Relaxation |

| . | . | . | ▲Education | ▲Relaxation | ||

| ◆Educational experience area | — | ◆Canteen | . | . | . | |

| ◆Cafeteria | — | ★Korean Identity | . | . | . | |

| ◆Educative experience area | — | ★Expand convenience | . | . | . | |

| . | . | . | . | . | . | |

| ★Garden experience | — | ★Expand convenience | ★Garden experience | — | ★Public relations | |

| ★Garden experience | — | ★Design Improvement | ★Garden education | — | ★Expand Convenience | |

| ★Garden Information | — | ★Design Improvement | . | . | . | |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kim, M.; Sung, J.-S.; Lee, J.-W. Perspectives on the Direction of the Suncheon Bay National Garden from Local Residents and Non-Local Visitors. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1832. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101832

Kim M, Sung J-S, Lee J-W. Perspectives on the Direction of the Suncheon Bay National Garden from Local Residents and Non-Local Visitors. Sustainability. 2017; 9(10):1832. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101832

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Moohan, Jong-Sang Sung, and Jin-Wook Lee. 2017. "Perspectives on the Direction of the Suncheon Bay National Garden from Local Residents and Non-Local Visitors" Sustainability 9, no. 10: 1832. https://doi.org/10.3390/su9101832