1. Introduction

Ensuring sufficient means of implementation (MOI) is a key but contentious aspect of the

2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development [

1], which includes the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In the negotiation of this agreement, arguments by developing countries that MOI should be highlighted by including them in each individual goal area in addition to a separate goal on MOI prevailed over efforts by developed countries to restrict MOI to a separate goal. Regarding finance, developing countries emphasized the importance of international assistance while developed countries, facing their own fiscal constraints, underscored the importance of expanding domestic sources of financing in each country and a greater role for the private sector. The final agreement included a broad range of MOI, including but not limited to finance.

However, the SDGs with their 17 goals and 169 targets can seem overwhelming, and a new discussion has arisen about whether countries should prioritize a few priority goals/targets rather than trying to tackle all of them. Some have criticized the SDGs for having too many goals and targets, and pursuing all of them would lead to diluted efforts and limited progress. Therefore, some argue that certain SDGs should be prioritized because they have better cost-benefit ratios. These arguments may reflect concerns that financial resources may be insufficient or not forthcoming [

2,

3,

4].

In contrast, this article argues that a broader view of MOI—not just focused on finance—should lead to a more optimistic outlook regarding the feasibility of achieving the SDGs. It also makes a related argument emphasizing the desirability of more integrated approaches to implementation.

The first main point is that most SDGs are in fact means themselves—in other words, intermediate goals—that contribute to the achievement of the higher goals of human health, wellbeing, and security. This point is obscured by the structure of SDGs, which blurs the fact that different goals have different functions, such as providing resources (including energy and water) or enabling environments (including health and education). This creates an artificial and unhelpful distinction between goals and targets on the one hand, and MOI on the other hand. The SDGs and their targets are a complex tangle of many interlinked intermediate goals and means, so it is easy to understand why one observer criticized them as “garbled” [

2]. This paper tries to sort out these chains of ends and means in a relatively simple conceptual framework to make it easier to visualize the linkages among the goals.

The second main point is that greater focus on the interlinkages and synergies among goals could enhance the effectiveness of implementation and also to some extent reduce the related costs. Therefore, SDGs should be implemented as a mutually supporting package to maximize the synergies and minimize trade-offs among the goals. “Prioritizing” some SDGs while neglecting others could unnecessarily raise costs and reduce effectiveness, especially when considering a longer timeframe, including development after 2030—the end-year of the SDGs. Understanding the goals as means could help stakeholders to see the interlinkages, synergies, and related potential to reduce costs, and incentivize them to adopt a more integrated perspective and foster cooperation.

Third, integrated implementation will require enhanced capacity, particularly for governance and coordination. Finally, this article analyses the arguments about the financial feasibility of SDGs, and concludes that while the upfront investments may seem high in absolute terms, they are not so high in comparison to global gross domestic product (GDP), global financial assets, and the overall expected benefits.

It is hoped that this article, especially its key concept of goals as means, will encourage policymakers as well as researchers to hold a more positive view of the desirability and feasibility of a comprehensive approach to implementing the SDGs, as well as allay any possible latent concerns about their financial feasibility. This article also hopes to encourage a much greater prioritization of capacity building, especially for governance and the implementation of integrated approaches. This has considerable potential to significantly scale up SDG implementation but is itself much less costly than large infrastructure-related investments.

The rest of this article is organized as follows.

Section 2 surveys past discussions of MOI and how it has been incorporated in the main agreements on sustainable development from Agenda 21 up to the SDGs and the 2030 Agenda.

Section 3 critiques how MOI is treated in the SDGs and the broader 2030 Agenda that incorporates them.

Section 4 develops a classification for the main elements of MOI from a broad perspective.

Section 5 develops a framework to show the linkages among the goals.

Section 6 makes the case for enhancing capacity for sustainability governance and coordination.

Section 7 discusses the financial feasibility of SDGs, and

Section 8 draws conclusions.

3. A Critique of MOI in the SDGs

The approach to MOI in the SDGs is not carefully thought out or systematic. How the specific MOI targets under each SDG relate to the MOI elements in SDG 17 is described in

Table 2. Each MOI target under Goals 1–16 is classified according to the seven categories of MOI which are listed under Goal 17. For example, Goal 2 has three targets related to MOI, and the first one, 2.a, can be classified as related to both finance and capacity building; 2.b can be classified under trade, while 2.c is difficult to classify under the Goal 17 elements. The table clearly shows that the linkages between the MOI under Goals 1–16 and the MOI under Goal 17 are not consistent. None of the seven MOI elements of Goal 17 (“Partnerships for the Goals”) was included consistently in each one of the other goals. Even finance was not specifically included as a target in five of the other Goals (5, 6, 12, 14, and 16). No goal had targets for all of the MOI elements. Most goals had only two or three targets related to MOI; only one (Goal 4) had four targets. There were also a few additional specific MOI elements that were listed as targets in specific goals, but do not correspond well with the MOI categories in Goal 17. Many of these are directly related to the specific goal, and might be more properly interpreted as part of the goal to be achieved rather than a means to achieve it, such as the tobacco control framework under health (Target 3.a) or creating a global strategy for youth unemployment (Target 8.b). Finance and capacity building were mentioned as targets in most of the goals, but not all. Policy coherence was mentioned as a target in nearly half of the goals, while technology and trade were specifically mentioned only in four goals (Targets 2.b, 3.b, 8.a, and 10.a). Partnerships were not mentioned specifically in any goals except for Goal 17. Thus, it is apparent that the overall approach to MOI in the SDGs is very ad hoc, and there was no systematic logic or concept that was followed.

A broader critique is that in the SDGs as a whole, the fundamental distinctions between goals and means are blurred, both between and within goal areas. For example, the elimination of poverty is clearly a goal. But other goals such as energy and infrastructure could be more logically considered as means to achieve human and social goals. They could also be considered as intermediate goals that are stepping stones to achieving higher level goals. Clearly, governments considered several means to be so important that their status was elevated to goals. Other goals may be considered as both goals and means. Education may be the clearest example of this. On the one hand, education is desirable for its own sake, and thus considered as a goal; on the other hand, education is also clearly a necessary means to achieving any other goal. Similarly, good health and clean water may also be desirable per se, but they are also necessary means to achieving most of the other goals. Even within specific goal areas, some targets that are not specifically designated as means may still be logically considered as means. Goal 2 on hunger is a prime case, as it addresses various aspects of agricultural production systems that are key means to reduce hunger as well as make agriculture more environmentally sustainable. Other examples include Target 1.3 on social protection systems, which are actually major means to combat poverty, or Targets 6.4 and 6.5, which recommend water-use efficiency and integrated water resources management, which are important means to improve water sustainability. Overall, the SDGs and their targets are a complex and tangled web of chains of interlinked goals and means.

The confusion between goals and means may be the sharpest in the cases of Goals 8 and 9 on economic growth and industrialization. Apparently, these are intended as means to achieve other goals such as poverty and hunger elimination, especially through the intermediate goal of providing people with decent work. While economic growth and industrialization were widely assumed to lead to these outcomes in the past, recent experience has questioned these assumptions as many parts of the world experience “jobless growth” and “jobless recoveries” and as many industries’ need for workers steadily decreases due to advances in productivity and technology [

10,

11,

12]. The concept of “green growth” holds out the possibility that economic growth could be made compatible with ecological constraints and provide decent work for all, but to what extent this is achievable is still an empirical question [

13,

14].

4. Main Elements of MOI from a Broad Perspective

There is a wide variety of types of MOI, as seen in the previous section. This section suggests how these may be usefully classified in order to highlight two aspects that should be given additional emphasis: human resources and governance.

This article divides MOI into four main categories—resources, capacity, data/information, and governance—as explained in

Table 3. Among the traditional elements of MOI, finance and technology can be considered as resources. This classification has several differences from the traditional classification (finance, technology, capacity building, trade, data and information, and partnerships) evident in the major agreements discussed in the previous section.

First, when resources are considered more broadly, it is apparent that human resources are not clearly indicated in discussions of MOI in major agreements related to sustainable development. They are implicitly included in the concept of capacity building, but the word capacity building itself could seem to refer to building capacity for existing human resources, not necessarily adding new ones. Classifying human resources as a separate element of MOI highlights the point that a significantly larger quantity of human resources is needed for many activities related to sustainable development. Of course the quality of human resources is also essential, and this is covered by capacity building.

Second, good governance is also often thought of as an enabler [

15]. In principle, there is nothing wrong with this, but it tends to be combined with a list of other enablers, which tend to obscure its importance—perhaps intentionally, since some governments may be uncomfortable with emphasizing the concept. However, governance is qualitatively different from other enablers such as capacity development or data and information. While there are many definitions of governance [

16,

17,

18], key common elements relate to various aspects of decision-making and institutions. Therefore, since decision-making is key to setting overall directions, it is better to classify governance in a separate category. In this way, the importance of laws, regulations, and policies can be more clearly highlighted. The concept of governance also more clearly underscores the importance of institutions and processes for decision-making and implementation, in particular the concepts of policy integration and coordination. This broad conception of governance easily encompasses many of its more specific elements and aspects such as accountability, transparency, access to information, participation, justice, etc.

Third, more traditional means of implementation such as laws, regulations, plans, enforcement measures, judicial review, etc., are generally not directly mentioned in global sustainable development agreements as means of implementation, but should be considered more explicitly. Certainly many of the SDG imply that laws or regulations, etc., would be needed to realize them, but this is generally not explicitly mentioned in the text of specific goals or the MOI targets. Creating a governance category may help to bring them back into the discussion. Sovereign nation-states are the decision-making members of the United Nations. Sovereignty resides in national governments. Only national governments have the authority to make laws and regulations, levy taxes, create binding judicial systems, maintain police systems with coercive power of enforcement, or delegate these powers to subnational governments or others. These powers may not have been sufficiently used to promote sustainability, and this has been one reason why there are relatively low expectations for nation-states and higher expectations for multi-stakeholder and participatory governance mechanisms and voluntary approaches [

18,

19,

20,

21]. Nevertheless, it may be worthwhile to increase consideration of how greater use of these more traditional measures could be encouraged.

Fourth, partnerships are typically heavily emphasized in global sustainable development agreements, much more so than laws, policies and decision-making procedures, which countries are rarely called on to change. This tends to shift the onus for action away from governments. While partnerships are certainly important, they may be better classified under governance, and higher level elements of governance, which belong to governments and have potentially far greater leverage—such as laws, policies, regulations, taxes, and spending—should be given greater emphasis. In addition, good governance can be a prerequisite for partnerships to be accountable and align with societal objectives.

Fifth, trade is typically strongly emphasized as MOI in global sustainable development agreements. In fact, this discussion has focused on trade agreements. For example, the 2030 Agenda calls for the completion of the Doha Development Agenda of the World Trade Organization [

1] (§ 68) and combatting protectionism [

8] (§ 83), rather than how trade itself could promote sustainability. Therefore, trade agreements are best considered as a kind of governance framework, rather than a direct MOI. Moreover, the main purpose of trade agreements is to promote increased trade volumes, while the actual economic and environmental effects of this trade may vary depending on specific circumstances [

22,

23,

24]. Therefore, incorporating measures in trade agreements to ensure that their environmental, social, and economic effects are positive rather than negative should be considered a governance issue [

25].

Finally, data and information were not traditionally featured as major MOI in

Agenda 21 or the

JPOI, although they put more emphasis on the broader role of research and scientific input. In contrast, in the SDGs, as seen in

Table 1, data and information play a central role, while research and science are somewhat less emphasized compared to the past. Data and information are expected to be the focus of major capacity-building initiatives as part of the SDGs.

5. Goals as Means

This section argues that the SDGs themselves should be seen as part of the MOI. This is related to the strong interlinkages between the goal areas. Because of these interlinkages, progress on one goal can reinforce progress in other goal areas. Conversely, lack of progress in one goal area can hinder progress in other goal areas. To be sure, there may also be trade-offs between some goals, where progress on one goal may hinder progress on another. This highlights the importance of understanding the interlinkages during implementation, since some solutions are able to create more synergies with other goals while others entail stronger tensions and trade-offs.

It is therefore essential to approach the SDGs in an integrated and coordinated manner, seeking the pathways that can maximize synergies and minimize trade-offs. The importance of an integrated approach is also highlighted by the

Global Sustainable Development Report [

26]

. The key point here is that although an integrated approach to the SDGs will require investments in capacity for coordination and analysis initially, such an approach will enhance the effectiveness of implementation and also help to reduce the costs of meeting the SDGs.

This systemic nature of the SDGs is not very evident from the SDGs agreement as such, as discussed in

Section 3 above, although the SDGs’ preamble refers to the goals as “integrated and indivisible”. [

1] (§ 55). Existing efforts to show how the SDGs are linked to each other can be divided into four main types. First, some focus on direct linkages between specific targets, which could be the basis for a network and/or quantitative analysis [

26,

27]. The International Resource Panel and the United Nations Environment Programme

(UNEP

) [

28] show how many goals and targets are interlinked through resources. A network analysis of the links among goals and targets based on the wording clearly shows many connections, although some are more connected than others, and it also shows that despite the complexity of the SDGs, many important environmental, social, and economic linkages are not addressed [

29]. This is useful for showing how specific targets are related to each other, but it does not easily indicate cause-effect relationships or put the goals and targets in a broader framework. Second, some discussions of linkages are organized according to the traditional three pillars of sustainable development (economic, social, and environmental) [

30]. The advantage of this approach is that it may be easier to understand and communicate since it is based on the traditional way of thinking about sustainable development. Accordingly, many governments may be interested in this classification. However, the disadvantage is that this disaggregation of the goals and targets back into the traditional three pillars does not contribute to the promotion of an integrated approach or to understanding how the goals are related. Third, the UN Secretary General proposed organizing the SDGs into six elements: people, dignity, prosperity, justice, partnership, and planet. However, this approach was not designed to show the interlinkages but rather to be concise (6 areas instead of 17) and easy to remember and communicate [

31]. Fourth, Griggs et al. [

32] proposed a streamlined goal framework based on six areas: thriving lives and livelihoods, sustainable food security, sustainable water security, universal clean energy, sustainable ecosystems, and governance. This is based on the logic that food, water, and energy are the basic human needs that support livelihoods, and these, in turn, are supported by ecosystems. This logic is certainly reasonable, but the linkages are not visible in the diagram developed by these authors. In principle, the SDGs could be rearranged according to this scheme, but several goals do not fit very well, especially those related to the economy (Goals 8, 9, 11, and 12) and social goals such as education (Goal 4), gender (Goal 5), and inequality (Goal 10). The approach taken by this article is related to the approach of Griggs et al. [

32] but expands it to classify and demonstrate the linkages between all 17 SDGs, and it highlights the key role played by economy.

So-called “nexus” studies conduct more in-depth analysis of linkages between a smaller number of areas. A prominent example is the “Food-Water-Energy Nexus” [

29,

33,

34,

35,

36] The basic idea behind this concept is that significant amounts of energy are needed to access water as well as produce food, while significant amounts of water are needed to produce energy and food. In particular, water shortages are beginning to threaten not only food but also energy production and energy security. In the future, more and more energy may be needed to provide water if desalination becomes more widely used. Therefore, energy, water, and food need to be managed in a more integrated way, also taking into consideration a range of related factors such as land availability, soil health, and impacts on biodiversity [

33,

34,

35,

36]. Understanding these linkages requires analytical capability, and managing them well requires sufficient capacity for cross-sectoral planning, implementation, and monitoring. Le Blanc [

29] observes that nexus studies have found a large number of linkages between various areas, and most are not included in SDG targets.

The framework proposed by this article explains the broad mutually supporting interlinkages between the SDG goal areas using three main elements. The first is a functional approach, which organizes the SDGs according to broad functions. Second, the framework is organized around the concepts of goals and means, which are the formal organizing principles of the SDGs, rather than the abovementioned traditional three pillars of sustainable development—society, economy, and environment—although it does incorporate them. Third, the functions and ends/means are organized along the process of production and consumption.

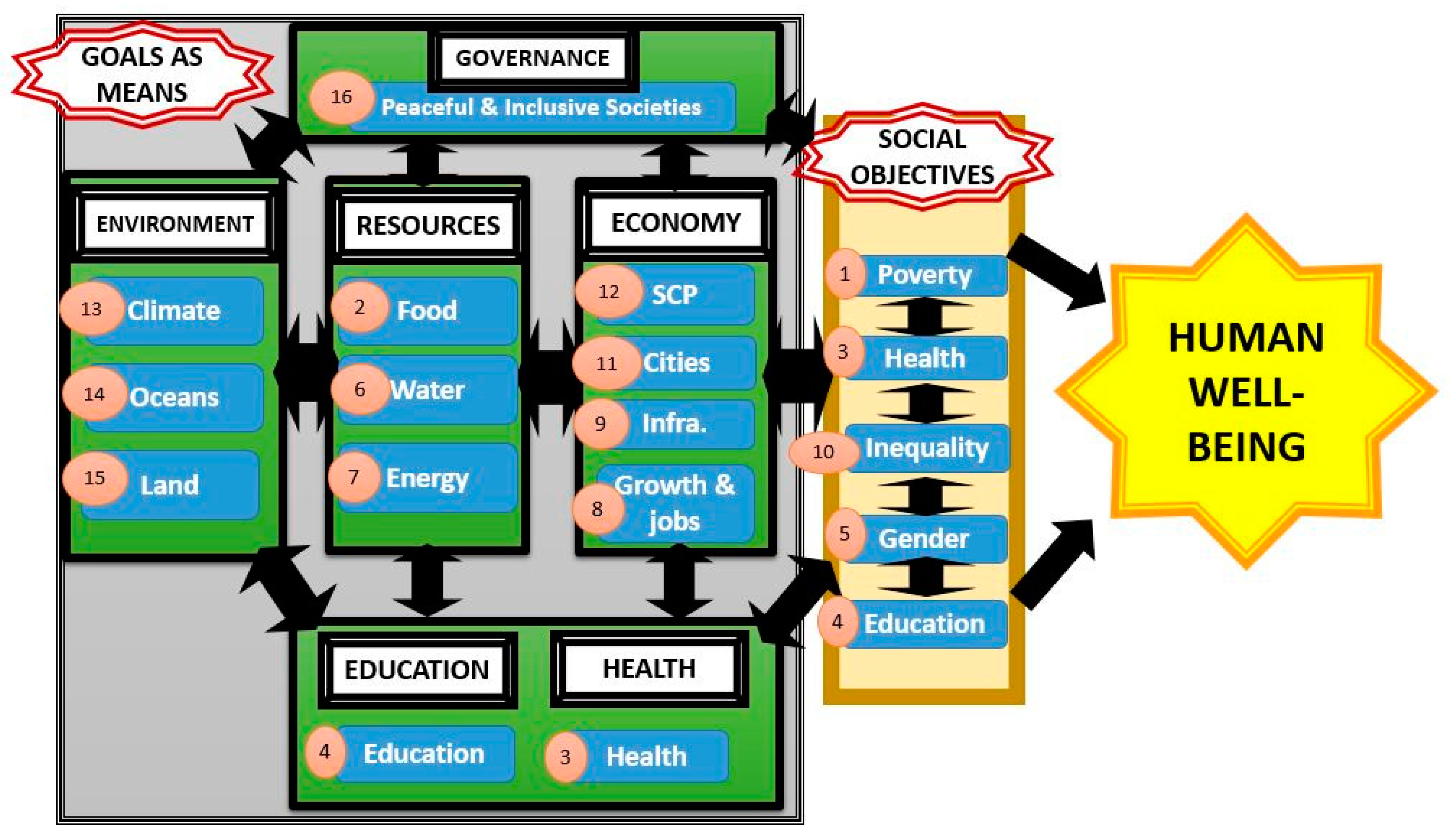

The SDGs can be classified into six main groups (functions) based on these ideas, as illustrated in

Table 4. The linkages among the goals are illustrated visually in

Figure 1. Thus, the environment is the foundation of the economy, social objectives, and ultimately, human wellbeing. The environment is the source of resources. Resources are the raw material for the economy. The economy provides goods and services that serve social objectives. Education and health are necessary for people to have the ability to extract resources from the environment and transform them through the economy. Governance refers to institutions and decision-making processes that govern how resources are extracted from the environment, how resources are transformed by the economy, how the results of the economy are transformed to meet social objectives, and how education and health are managed.

One limitation of this framework is that it does not fully and explicitly include the final step of the production–consumption chain, which is waste and pollution. It is visible to some extent in

Figure 1, especially relating to the production of resources, which generates pollution that harms the environment. However,

Figure 1 does not show the effects of pollution caused by economic activity and the achievement of social objectives such as poverty reduction. Pollution and waste come from both production and consumption, which may both be considered part of the economy, although consumption could also be considered as part of the achievement of social objectives. In fact, several SDG targets do address various kinds of pollution and waste including water sanitation and quality (Targets 6.2 and 6.3), air pollution and municipal waste (Target 11.6), food waste (Target 12.3), and marine pollution (Target 14.1). Future research could extend this framework to more systematically address waste and pollution; this article takes the first step, focusing on developing a simplified but systematic way to think about the relationships among the goals.

Although the governments formally organized the SDGs around goals and means, in practice it is not easy to distinguish what is a goal and what is a means, partly because of the inherent complexity of the interlinkages between the goals. In fact, these complex interlinkages are composed of chains of goals and means. For example, energy (Goal 7) is a means needed to produce water, and water (Goal 6) produces energy and is a means needed for industrial production as well as reducing poverty and enhancing health. Likewise, energy production produces greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and various types of air and water pollution that undermine health and worsen poverty. Thus, each goal area and target may be both a cause and effect (or means and goal) in relation to other goals.

5.1. Overarching Goal

The first point to be considered is the overarching goal or objective. The

2030 Agenda and the SDGs suggest that sustainable development is the overarching goal (since the label of “Sustainable Development Goals” is used), although they do not state this explicitly, and the actual text of the

2030 Agenda seems to avoid making a clear statement in the preamble, introduction, and vision [

1]. Clearly, the

2030 Agenda puts the highest priority on poverty eradication, stating in the Preamble that it “is the greatest global challenge and an indispensable requirement for sustainable development” [

1]. Also, the International Council for Science (ICSU) and the International Social Science Council (ISSC) [

27] (p. 9) suggested that establishing an overarching goal would be beneficial, such as “a prosperous, high quality of life that is equitably shared and sustainable”. The

2030 Agenda highlights people, planet, prosperity, peace, and partnership in the very beginning before the introductory section [

1], so these could be considered as suggesting overarching goals.

In order to more clearly highlight the relationship chains between ends and means in the SDGs, this article proposes the concept of human wellbeing as a reasonable overarching objective. This concept appears in a few places in the text of the 2030 Agenda, and logically may be considered as the overarching objective. This concept may facilitate understanding of the point that the environment is the foundation of human prosperity, which is the central message of the planetary boundaries concept. Another advantage is that it facilitates moving beyond GDP as a measure of wellbeing and implies that wellbeing may be achieved by other means besides economic (GDP) growth.

5.2. Social Objectives

Several SDGs can be classified as social objectives, which in a sense are key stepping stones on the road to human wellbeing. These goals—poverty reduction (Goal 1), health (Goal 3), education (Goal 4), gender (Goal 5), and inequality (Goal 10)—can be considered to set a minimum standard for human wellbeing. There may be other kinds of social objectives, but these are the ones that are prioritized in the SDGs. These social objectives are also related to each other in complex cause-effect chains. For example, inequality (Goal 10) may be one cause of poverty (Goal 1), poor health (Goal 3), and insufficient education (Goal 4), and gender equality (Goal 5) can also be considered as a means to achieving all of the other SDGs.

5.3. Resources

Food, water, and energy are resources needed to achieve social objectives such as poverty reduction and good health. Therefore, strictly speaking, resources should be considered as means; they are not really goals in and of themselves. However, governments included them as headline goals in the SDGs, probably due to their essential role in achieving the social objectives, especially for reducing poverty. Arguably, food, energy, and water are among the most important resources, so it was reasonable to prioritize them in the SDGs.

Resources under SDGs may be considered to have two aspects, access and environmental sustainability [

37,

38]. Enhanced access to these resources by poor people is necessary for poverty reduction. At the same time, extraction or production of these resources has environmental consequences that in turn may offset the benefits from access, leading to problems with sustainability. Thinking about these goal areas as resources helps to focus thinking on the need to reconcile the aspects of access and environmental sustainability, and manage key resources such as energy and water in a coordinated and integrated manner.

Resources are also characterized by complex ends-means chains. Certainly food, energy, and water are directly consumed by people to support their daily living. In addition, as mentioned above, they are needed to produce each other: water is needed to produce both food and energy, and energy is needed to produce food and water. Water and energy are also key inputs into the broader economy, as they are needed, directly or indirectly, to produce virtually all other goods and services. The production of resources also causes pollution and GHG emissions.

5.4. Environment

Resources, in turn, come from the environment and ecosystems, and resource extraction often causes GHG emissions and various other forms of pollution. Major environmental issues highlighted in the SDGs are climate, oceans, and land (13–15). Water (Goal 6) is also a separate goal, and could be considered part of the environment as well as a resource, although this classification considers it more as a resource. It can be observed that out of the three main environmental elements—land, water, and air—only land and water have their own goal area, while climate highlights only one specific aspect of air and does not highlight air pollution in general. To be sure, air pollution is incorporated in Goal 11 on cities and Goal 3 on health, but it is not well emphasized; moreover, this aspect is only partial—in theory, air pollution outside of cities is not included.

The concept of “planetary boundaries” [

39] is an attempt to define safe biophysical limits to humanity’s alteration of the ecosystems upon which society depends. However, a number of governments have not accepted the idea of planetary boundaries [

40], and these are not referred to in the

2030 Agenda. Nevertheless, clearly showing how these resource-related goals are related to the environment could hopefully make it easier for skeptics to see how the SDGs are linked to planetary boundaries and facilitate consideration of how to link the other planetary boundaries with future SDG implementation.

5.5. Economy

The economy allocates resources and organizes production. It also processes resources into goods and services needed for achieving social objectives. Therefore, it is clear that the functioning of the economy—what needs and demands are met and in what ways, and how different kinds of work are rewarded—plays a critical role in achieving sustainable development.

Sustainable consumption and production (SCP) should be the key organizing principle of the economy. SCP is included in the SDGs as a separate goal (Goal 12) but the targets agreed under that goal do not provide a clear direction for how to align the economic system, including the institutions that shape investment flows and patterns of consumption and influence how surplus value is used, with sustainability objectives.

Three other SDGs have major economy-related targets. Goal 11 on cities includes housing (Target 11.1) and transportation systems (Target 11.2), which are major economic sectors. Goals 8 and 9 are explicitly focused on the economy: Goal 9 focuses on infrastructure, industrialization, and innovation, and mostly encourages these to be sustainable. In addition, targets also address small-scale enterprises (Target 9.3), resource use efficiency (Target 9.4), scientific research and technology (Targets 9.5 and 9.b), and information and communications technology (Target 9.c). Goal 8’s full headline is “sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all” [

1]. This headline seems to be not fully oriented towards sustainability, and does not use more sustainable concepts such as

green economy or even

green growth. Nevertheless, the focus on jobs is crucial, and Target 8.4 emphasizes the importance of decoupling economic growth from environmental degradation, as well as resource efficiency.

5.6. Education and Health

Education and health are special cases, since they are both means and ends. Education and health are important elements of human wellbeing, so they are classified as social objectives. However, they are also means to achieve the other goals, by providing enabling environments so they are also classified as means of implementation and are each included in two places in

Figure 1.

5.7. Governance

The word governance is not directly mentioned in the SDGs, but Goal 16 on peaceful societies is generally considered to be the SDG related to governance. To highlight the concept of governance in this classification calls attention to the other aspects of governance that are missing from the SDG framework itself. Governance is regarded in the framework of this article as the central MOI, and it is necessary for the mobilization and effective deployment of all of the other MOI. Good governance, broadly speaking, is not necessarily a goal in itself, but rather may be considered as an important means to achieve human wellbeing. Still, Goal 16 is focused on peaceful societies, and peace is reasonably considered a worthy goal in itself.

One advantage of the framework of this article is that it makes it easier to identify gaps in the SDGs in terms of missing or de-emphasized issues. Although 17 goals and 169 targets may seem like a lot, in fact, they are not fully comprehensive. For example, if the environment is considered as a category, then air pollution’s de-emphasized position (as part of Targets 3.9 and 11.6) becomes apparent in contrast to the headline goal status achieved by land, oceans, and climate (Goals 13–15) [

41]. The most important resources may be energy, water, and food, but others, particularly metals and minerals, are not visibly highlighted in the SDGs. Metals and minerals are critical inputs for the economy, especially for industrialization (in Goal 9) and also for renewable energy (in Goal 7), but they are also responsible for significant water and land pollution (in Goals 6 and 15) and air pollution (under cities in Goal 11) as well as the resulting health problems (Goal 3).

6. Capacity for Sustainability Governance

This paper emphasizes the need for capacity building for improved governance, and especially the institutional capacity of governments to integrate sustainability principles across sectors and policy domains. This would enable governments to play a stronger role in implementation, ensure a better coherence and consistency of supporting policies, and thereby increase the likelihood that countries make good progress towards achieving the SDGs. While much of the existing discussion has focused on capacity needs of developing countries, capacity strengthening for improved policy integration may also be needed in developed countries. The need for such capacity building has been recognized at least since the Rio Summit in 1992 but existing international efforts to strengthen governance capacity only partly address this need. Existing capacity building programs tend to focus on improving elements of good governance in general, including the broad concepts of accountability, transparency, and multi-stakeholder participation, rule of law, and degree of corruption [

16,

17]. The World Bank’s Open Government Partnership [

42] is an example of a major international effort to strengthen capacity for good governance in this general sense. To be sure, these elements of governance are certainly important and thus often included in international agreements, but they assume that governments already have basic capacities to formulate and implement coherent evidence-based policies, and just need some transparency and accountability mechanisms and multi-stakeholder encouragement to persuade them to shift policies and public spending in the “right” direction. Many governments, however, especially but not only in developing countries, do not necessarily have sufficient basic capacity or tools to perform with reasonable quality the tasks they are formally in charge of [

43,

44,

45].

Strengthening national statistical capabilities is an element of governance that has been emphasized in the discussions on the SDGs. Such capacity is crucial not only to measuring the progress of SDGs implementation, but also to designing effective policy interventions and to rational resource allocation. Assessments of the need for capacity strengthening in this area have been carried out and efforts to enhance statistical capacity are being planned [

46]. Nevertheless, while better data is important, the SDGs will not be implemented by statistics and indicators; strengthening other aspects of governments’ capacity is still necessary.

This paper proposes five key ways in which governance capacity should be strengthened in order to increase the likelihood of achieving the SDGs, based on the discussions in preceding sections. The first priority is related to the recognized need for an integrated approach to the SDGs that can maximize the synergies while minimizing trade-offs and costs. This requires enhanced coordinating capacity in each government. Governments are still to a high degree organized in vertical silos and have weak coordinating capacities, especially related to sustainability [

47]. Without greater coordination capacity, even if implementation of individual SDGs goes reasonably well, it will be difficult to achieve synergies among SDGs, and achievements in some SDGs may offset progress in others, thereby raising the overall costs and reducing overall effectiveness. At a minimum, some institutional infrastructure will be needed simply to keep track of progress and coordinate national reporting. Some kind of institutional mechanism is needed with some authority to require coordination among line ministries. Some countries already have bodies with at least some coordination functions, such as China’s National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) [

48], South Korea’s Presidential Committee on Green Growth [

49], and Mongolia’s Ministry of Environment and Green Development [

50]. Establishing such an apex body does not necessarily require a significant increase in budget or staff, but the staff need to be capable, and appropriate mandates and authority are needed.

The second priority is to develop and strengthen national domestic fundraising capacity. This point was emphasized in the

AAAA [

8]. Although some existing public expenditures may be reclassified or shifted to other purposes, augmenting government budgets through taxes or other types of charges or fees seems, at least to some extent, unavoidable. This ideally involves international action to address loopholes that allow tax evasion, but also, with limited progress on reforming the international tax regime, strengthened domestic capacity for tax collection can still be highly beneficial and can be a very cost-effective form of development assistance [

51]. However, even with such efforts to strengthen public finances, there will be a need to mobilize private investments and ensure that such investments in general are better aligned with SDG objectives. Such a shift in the rules of the game for private investments is unlikely to happen without governments playing a major role. There are several ways for governments to do so, in addition to the blended finance that has been highlighted in relation to the SDGs, including reforms of fiscal systems to tax bads rather than goods, phasing out of harmful subsidies, and expanded use of regulations that require private actors to make certain investments or cover certain costs. Renewable portfolio standards that require electric power companies to shift a certain percentage of their generation capacity to renewable energy, or require employers to contribute health insurance payments to their workers, are examples of how government regulations can mobilize private capital and reduce the need for public spending. However, for governments to be able to effectively use such approaches requires sufficient capacity for policy development and implementation—capacities that in many cases would need to be strengthened.

The third priority is to develop institutional capacity or mechanisms to ensure that each government’s own spending and regulations are well aligned with the SDGs, or at least do not conflict with any of its goals and targets. This is basically a proposal to build capacity to conduct sustainability assessments of all government spending and regulations, and would be applied to all ministries (cf. the discussion above on mechanisms for policy assessment). It should also apply at subnational levels, not just national levels. This would be similar to regulatory impact analyses and cost-benefit analyses such as those conducted in the United States by the Office of Management and Budget and other US government departments and agencies [

52,

53]. Regulatory impact assessment is mandated by the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in Chapter 25 on regulatory coherence [

54], so TPP countries, if the agreement is ratified, will need to set up assessment mechanisms anyway. Of course, cost-benefit analyses are a good idea, but these should be conducted in terms of broader sustainability criteria. This article argues that assessments of laws, public policies, and government spending should focus on sustainability, not just on traditional cost-benefit analysis or whether they are trade-neutral. This may be implemented through existing budgetary allocation mechanisms. A limited focus on sustainability assessment of budget proposals would not necessarily need a large amount of new staff and budget, and might be able to utilize existing institutional mechanisms. However, a broader and more comprehensive regulatory assessment system may need significant additional human resource capacity. If sustainability assessment is linked to regulatory assessment under trade agreements, this capacity will need to be developed anyway, and presumably some could be funded by trade capacity development assistance.

Fourth, multi-stakeholder participation is widely recommended as a key governance mechanism to promote sustainable development [

55,

56]. Some countries, including some developing countries, have developed various mechanisms to include multi-stakeholder participation in decision-making and implementation in some policy areas [

57]. However, governments of many countries, especially developing ones, may need additional capacity for such processes. Even in countries that have these processes, there may be room to improve their effectiveness or expand their scope.

Finally, in general, the human resource capacity of government officials in many existing ministries and departments in many countries will need to be strengthened, in terms of both quantity and quality. The scope of the SDGs encompasses most ministries, if not all, in many countries, including those in charge of agriculture, economy, education, environment, development, finance, health, industry, labor, local governments, planning, water, and even defense and police. Especially in developing countries, ministries in charge of these areas may not have enough human resources with sufficient capacity to implement related SDGs, even with larger budgets. Governments’ rules and procedures for recruitment and remuneration may need to be revised to make it easier to hire and retain capable civil servants, and to keep them motivated and accountable.

7. Finance

While this paper emphasizes the significance of capacity building and governance, there is no doubt that the issue of finance also needs to be addressed. Securing the financial resources for meeting SDGs can seem daunting, but this paper makes three main arguments about why financing should be feasible.

First, it is necessary to consider the scale of financing needs in a broader perspective, in comparison with the overall size of the world economy, world wealth, and world savings. A rough estimate of the additional investments necessary for SDGs, beyond those already planned, amounts to about 2 or 3 trillion USD, which seems like a large amount of money. However, world GDP in 2014 was 78 trillion USD, while global financial assets totaled 273 trillion USD. The world’s annual savings was 17 trillion USD, and 46% of this was from developing countries. The world’s taxes amounted to over 22 trillion USD, or 28.4% of global GDP. These kinds of comparisons usually mention military spending, which amounted to 1.8 trillion USD in 2014, about 2.3% of world GDP. These figures are summarized in

Table 5.

Therefore, the cost of SDGs would be about 2.5%–3.8% of world GDP, and 0.7%–1.1% of global financial assets. Is this a lot of money, considering what the SDGs seek to achieve in terms of enhanced and lasting human wellbeing? In conventional terms, many people may consider it to be a lot. However, it is clearly not so big that it would cause a major disruption in the global economy or even a major financial burden. Many shifts in economic trends or spending can be significantly larger, such as the burgeoning share of health care in the U.S. economy, which expanded from about 5% of GDP in 1960 to almost 19% in 2016 [

58], or large shifts in military spending [

59].

The value of sustainability benefits also needs to be considered, not just the costs. The authors are not aware of any effort to estimate the value of the total benefits of SDGs. Nevertheless, there are general estimates of the value of ecosystem services, which is a key area to be protected by SDGs. The total value of global ecosystem services has been estimated at 125 trillion USD, according to one widely cited estimate [

60], which is 60 percent larger than world GDP. There is a separate estimate more narrowly focused on marine and coastal ecosystems, which estimates their market value at 3 trillion USD and their non-market value at 21 trillion USD. These are 3.8% and 26.9% of world GDP, respectively (see

Table 6). Presumably, the benefits from strengthened education, better health care, and other SDGs would also be of a very large magnitude.

The costs of damage to the environment and health also need to be considered. The WHO estimated that, globally, around 7 million deaths could be attributed to air pollution in 2012, and air pollution is now the world’s largest health risk [

61]. In China, the World Bank estimated that environmental problems reduced GDP by 9% in 2008, and China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection estimated that pollution cost about 3.5% of GDP in 2010 [

62]. If, over the next 15 years, efforts to achieve the SDGs could drastically reduce these impacts, this would clearly be of great benefit to society.

The second argument is that much of the funding could come from reallocating or relabeling existing funds. Not all of the spending for SDGs needs to be additional to current and planned expenditures. For example, very large investments in energy, infrastructure, etc. are already planned. Much of the energy investment is planned to go to fossil fuels, but a large share could be shifted to renewable energy with little or no need for additional funds. Fossil fuel subsidies could be redirected to expand renewable energy, as is already happening to some extent in a number of countries, including developing as well as developed ones. Some existing spending, such for health or education, may already be contributing to SDGs, so designating it for SDGs would be mainly a matter of labelling. It may also be possible to increase the effectiveness of how money is spent by reallocating from curative measures or defensive spending to prevention. In health care, for example, reallocating some funds currently spent on treating welfare diseases to promotion of healthier lifestyles could enhance health outcomes and most likely also reduce societal costs.

Several more specific suggestions could be made for how to reallocate existing funding or channel new money into SDGs. A certain share of national budgets should be designated to apply to specific SDGs. This should be embedded in budgeting guidelines of ministries of finance and reflected in criteria for national project financing. This would facilitate mainstreaming. Sustainable or green public procurement policies have already been adopted to some extent by a number of countries, but all countries should adopt them, and they should apply more broadly and systematically. Ideally, public procurement rules should also include social criteria in addition to environmental ones. The Sustainable Public Procurement (SPP) Programme under the SCP 10-Year Framework of Programmes could be used to support the implementation [

63]. Overseas development assistance (ODA) budgets should be channeled towards addressing SDGs. UN agencies and Multilateral Development Banks (MDBs) should also designate a certain share of their operating budgets towards specific SDGs. A subset of these should be allocated to cross-cutting issues that otherwise risk getting low priority.

The third argument is that there is room to increase taxes modestly in order to fund SDGs. World taxes as a percent of GDP are 28.4%. In traditional terms, increasing this by 2 or 3 percentage points is quite significant, but it cannot necessarily be interpreted as a huge burden or a complete economic restructuring. To be sure, governments in many developed countries, especially in Europe, spend considerably more than this. However, many developed countries spend considerably less, so they should have room to expand their own domestic fiscal resources to help themselves. Tax collection effectiveness is also rather low in many countries; with more capacity, governments could collect more of the taxes that are already due. Discussions are also ongoing on how to address issues of tax evasion, and if these discussions lead to effective measures being implemented this could significantly increase public resources—especially in many developing countries. This illustrates how the two themes of this paper—the need for strengthened governance capacity and funding for the SDGs—are linked.

Overall, the funding does not need to come only from taxes on current income, consumption, and profits. A significant amount of resources could be generated by a small increase in taxes on financial assets and/or taxes on financial transactions. Borrowing, of course, could also be used. Thus, theoretically, 1% of global GDP raised by a combination of each of these three measures could generate 3% of global GDP in revenue. Again, these costs should be considered along with benefits. This spending is basically an investment that will generate returns, so the spending does not just disappear, but rather would generate regular returns and create jobs. Thinking of the financing issue from this perspective makes it appear considerably more feasible and realistic.

8. Conclusions

This paper has three main messages and two main recommendations regarding the means of implementation for SDGs. The first message is that MOI should be considered in a broad sense, with much more emphasis on capacity building and governance rather than a narrow focus on finance. In principle, this message is not really new, but the message bears repeating since many governments may still be unconvinced. Therefore, the second main message is that it is important to see the goals themselves as MOI, since they are closely interlinked. Because the goals are interlinked, they should be implemented using an integrated approach that will help produce cost-saving synergies, and avoid cost-increasing trade-offs. Clearly governments did not think of goals as means during the SDG negotiations, but it is hoped that this concept might help governments to understand the advantages of an integrated approach and become more optimistic about the feasibility of implementing the SDGs. The third main message is that, even in terms of finance, the overall costs are modest and affordable, especially when compared with relevant global financial indicators such as GDP and wealth. It is also necessary to consider financing as an investment rather than a cost, and consider the benefits and investment returns rather than just the initial spending amount.

The first main recommendation is to prioritize capacity building, especially for governance. Otherwise, it will be difficult to implement an integrated approach, and the effectiveness of all means of implementation will be reduced. Spending for capacity building is significantly less than initial investment outlays for sustainable infrastructure; in addition, it directly creates jobs. Strengthened capacity and governance will greatly increase the efficiency and effectiveness of spending and investments.

The second main set of recommendations relates to how to increase financing. The easiest and least costly way is to reprogram existing spending and investment from unsustainable to sustainable activities. Regulation can be used to mandate private companies to make these shifts. Sustainability impact assessment can be used to shift both existing and new regulations. Existing government spending can be shifted through sustainability budgetary assessment and sustainable public procurement policies. Making these shifts happen requires sufficient governance capacity, and in most countries a strengthening of such capacity is likely to be needed; this second recommendation is thus linked with the first one. Finally, as discussed earlier, the overall cost is modest compared to global GDP and wealth, so that some of the funds could be raised by raising taxes on GDP and wealth, even just 1% each, or even through borrowing. Again, it is important to understand that much of this spending should be considered as an investment that will generate future returns.

Some are recommending a selective approach to the SDGs, which involves focusing on just a few SDGs based on a country’s priorities. In principle this idea sounds attractive, but the danger is that cost synergies will be lost, and the way one goal is pursued may harm the progress of other goals, thereby raising the costs and reducing the effectiveness of SDG implementation. Therefore, this paper recommends focusing on strengthening coordination and governance capacity in the early stages of SDG implementation.