Perspectives on Sustainable Resource Conservation in Community Nature Reserves: A Case Study from Senegal

Abstract

:1. The Erosion of Biodiversity: Drivers and Concerns

2. Community Conservation and Sustainable Development

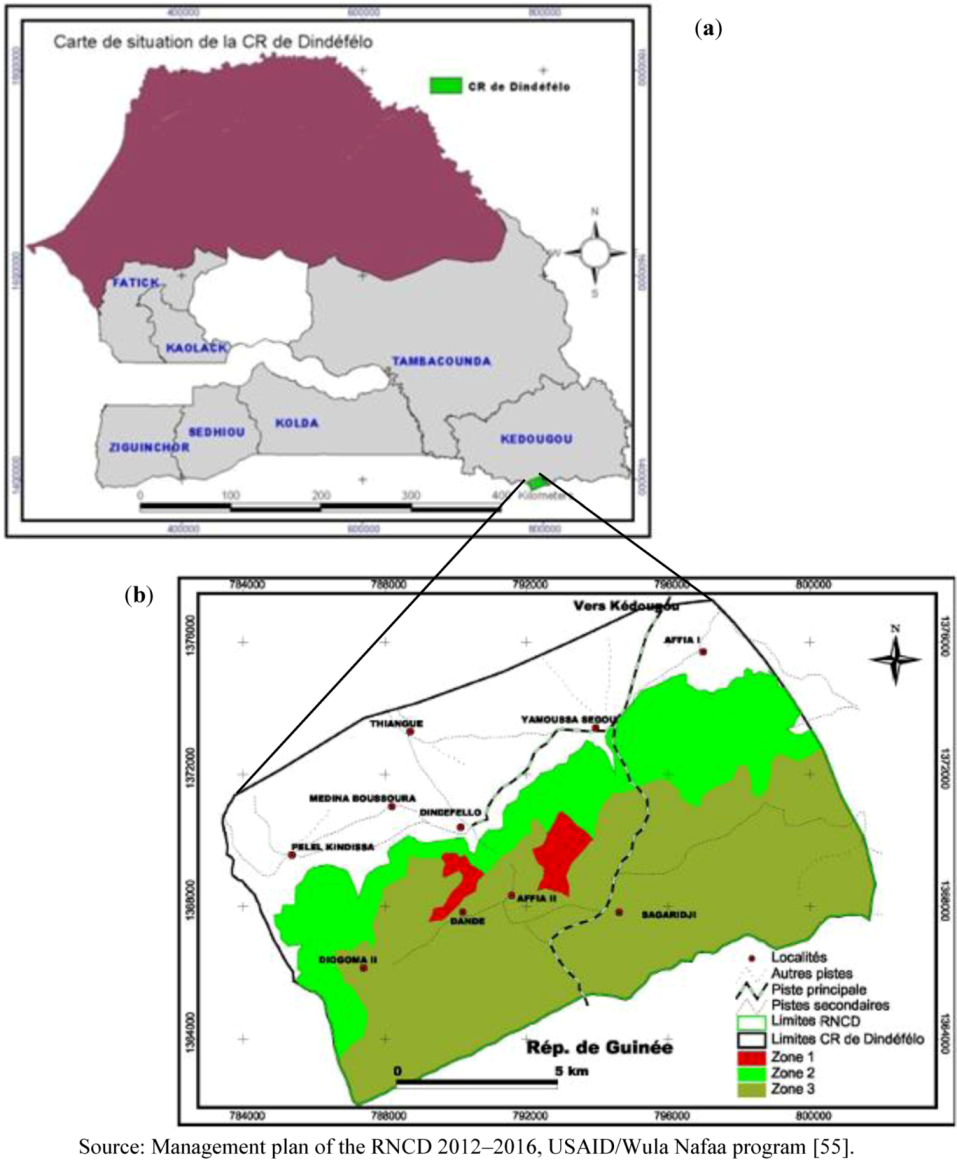

3. The Community Nature Reserve of Dindéfélo—A Study Case

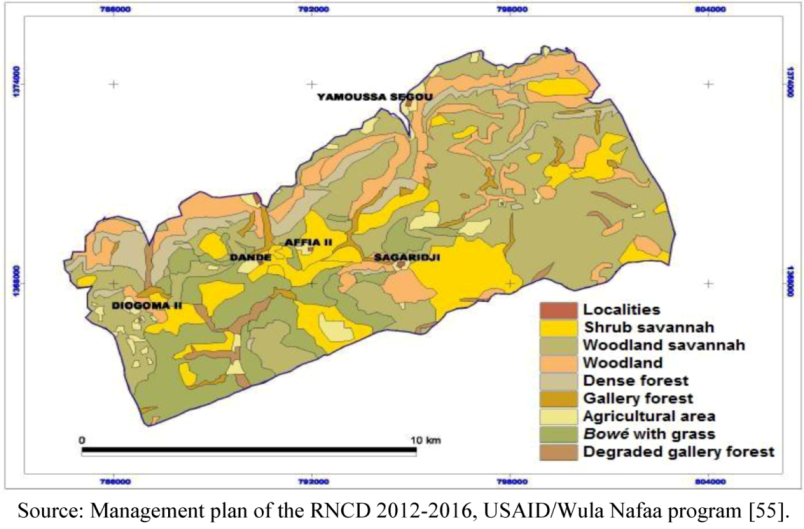

3.1. Context, Data and Forest Profile

| Type of land use | Surface Area (ha) | Surface Area Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Woodland and herbaceous savannah | 4860 | 37% |

| Forests (all types) | 3197 | 24% |

| Shrub savannah | 2430 | 18% |

| Bowé and prairie grass | 2174 | 16% |

| Agricultural areas | 512 | 4% |

| Others (houses, rocks,…) | 128 | 1% |

| TOTAL | 13.301 | 100% |

3.2. Examples of Sustainable Projects in Natural Protected Areas and Future Challenges

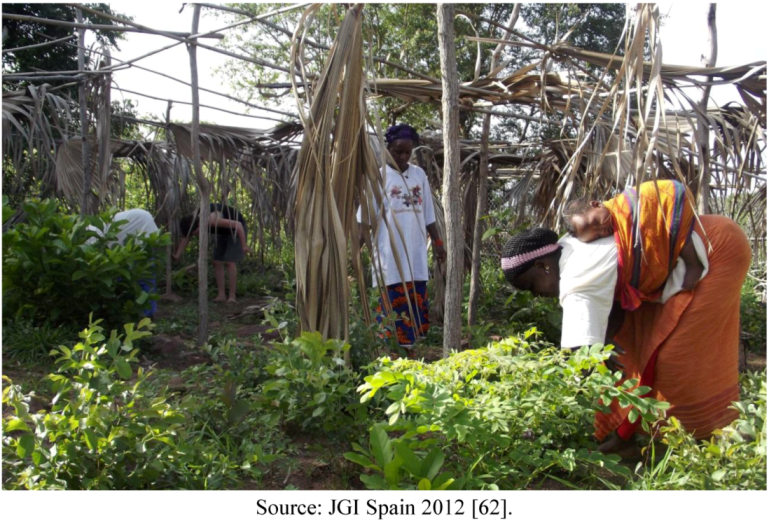

3.2.1. Nurseries as an Alternative to the Unsustainable Exploitation of Forest Fruits

3.2.2. Live Fencing: A Strategy for Sustainable Resource Conservation

3.2.3. Construction of Municipal Washing Facilities: An Example of Sustainable Policy-Making

4. Concluding Remarks

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Simsik, M.J. The political ecology of biodiversity conservation on the Malagasy Highlands. Geo. J. Lib. 2002, 58, 233–242. [Google Scholar]

- Borghesio, L. Biodiversity erosion in the Vadua Nature Reserve (Turin, Piedmont, NW Italy). Rivista Piemontese di Storia Naturale 2004, 25, 371–389. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, T.P.; Jackson, S.T.; House, J.I.; Prentice, I.C.; Mace, G.M. Beyond predictions: Biodiversity conservation in a changing climate. Science 2011, 332, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, S.D.; Droop, S.J.M.; Gregerson, P.; Henson, L.; Leon, C.J., Villa-Lobos; Synge, H.; Zantovska, J. Plants in Danger. What Do We Know? 1st ed; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Pimm, S.L.; Russell, G.J.; Gittleman, J.L.; Brooks, T.M. The future of biodiversity. Science 1995, 269, 347–350. [Google Scholar]

- Akeroyd, J. A rational look at extinction. Plant Talk 2002, 28, 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Vié, J.-C.; Hilton-Taylor, C.; Stuart, S.N. Wildlife in a Changing World—An Analysis of the 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, 1st ed; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Brummit, N.; Bachman, S. Plants under Pressure, a Global Assessment. The first Report of the IUCN Sampled Red List Index for Plants, 1st ed; Royal Botanic Gardens: Kew, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Daily, G.C. Nature’s Services: Societal Dependence on Natural Ecosystems, 1st ed; Island Press: Washington, D.C., USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, Ecosystems and Human Well-Being: Synthesis, 1st ed; Island Press: Washington, D.C., USA, 2005.

- Bandeira, S.O.; Albano, G.; Barbosa, F.M. Diversity and Uses of Plant Species in Goba, Lebombo Mountains, Mozambique, with Emphasis on Trees and Shrubs. In African Plants: Biodiversity, Taxonomy and Uses, 1st; Timberlake, J., Kativu, S., Eds.; Royal Botanic Gardens: Kew, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- van Wyk, B.-E.; Gericke, N. People’s Plants: A Guide to Useful Plants of Southern Africa, 1st ed; Briza Publications: Pretoria, South Africa, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO), World Health Organization Traditional Medicine Strategy 2002–2005, 1st ed; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- Khumbongmayum, A.D.; Khan, M.L.; Tripathi, R.S. Sacred groves of Manipur—Ideal centres for biodiversity conservation. Curr. Sci. India 2004, 87, 430–433. [Google Scholar]

- Antwhal, A.; Gupta, N.; Sharma, A.; Anthwal, S.; Kim, K.-H. Conserving biodiversity through traditional beliefs in sacred groves in Uttarakhand Himalaya, India. Resour. Conserv. Recy. 2010, 54, 962–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okafor, J.C. Amélioration des essences forestières donnant des produits comestibles. Unasylva 1991, 42, 1991–1992. [Google Scholar]

- Savy, M. Diversité, variété alimentaire et état nutritionnel des mères de jeunes enfants en milieu rural défavorisé. MSc Dissertation, Ouagadougou University, Burkina Faso, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Soubeiga, K.J. Analyse de la demande des produits forestiers non ligneux dans l’alimentation des ménages ruraux: Cas des départements de Bondoukuy (Mouhoun) et Niandialia (Boulkiemdé). BSc Dissertation, Université Polytechnique de Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Codija, J.T.C.; Assogbadjo, A.E.; Ekue, M.R.M. Diversité et valorisation au niveau local des ressources végétales forestières alimentaires du Bénin. Cahiers agricultures 2003, 12, 321–331. [Google Scholar]

- Ouédraogo, A.; Thiombiano, A.; Hahn-Hadjali, K.; Guinko, S. Diagnostic de l’état de dégradation des peuplements de quatre espèces ligneuses en zone soudanienne du Burkina Faso. Sécheresse 2006, 17, 485–491. [Google Scholar]

- Thiombiano, D.N.E.; Lamien, N.; Dibong, S.D.; Boussim, I.J. État des peuplement des espèces ligneuses de soudure des communes rurales de Pobé-Mengao et de Nobéré (Burkina Faso). J. Anim. Plant. Sci. 2010, 9, 1104–1116. [Google Scholar]

- Shankar, U.; Hedge, R.; Bawa, K.S. Extraction of non-timber forest products in the forests of Biligiri Rangan Hills, India. 6. Fuelwood pressure and management options. Econ. Bot. 1998, 52, 320–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalle, S.P.; de Blois, S. Shorter fallow cycles affect the availability of non-crop plant resources in a shifting cultivation system. Ecol. Soc. 2006, 11. Available online: http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol11/iss2/art2/ (accessed on 8 June 2012).

- Guariguata, M.R.; Cronkleton, P.; Shanley, P.; Taylor, P.L. The compatibility of timber and non-timber forest product extraction and management. Forest Ecol. Manag. 2008, 256, 1477–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meffe, G.K.; Carroll, C.R. Principles of Conservation Biology, 1st ed; Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lykke, A.M. Local perceptions of vegetation change and priorities for conservation of woody-savanna vegetation in Senegal. J. Environ. Manage. 2000, 59, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salafsky, N.; Cauley, H.; Balachander, G.; Cordes, B.; Parks, J.; Margoluis, C.; Bhatt, S.; Encarnacion, C.; Russel, D.; Margoluis, R. A systematic test of an enterprise strategy for community-based biodiversity conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2001, 15, 1585–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toledo, V.M. Biodiversity and Indigenous Peoples. In Encyclopedia of Biodiversity, 2nd; Levin, S.A., Ed.; Academic Press: Utah, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Alcorn, J. Indigenous peoples and conservation. Conserv. Biol. 1993, 7, 424–426. [Google Scholar]

- Jusoff, K.; Majid, N.M. Integrating needs of the local community to conserve forest biodiversity in the state of Kelantan. Biodivers. Conserv. 1995, 4, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkes, F. Community-based conservation in a globalized world. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 15188–15193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter-Bolland, L.; Ellis, E.A.; Guariguata, M.R.; Ruiz-Mallén, I.; Negrete-Yankelevich, S.; Reyes-García, V. Community managed forests and forest protected areas: An assessment of their conservation effectiveness across the tropics. Forest Ecol. Manag. 2012, 268, 6–17. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, W.M.; Aveling, R.; Brockington, D.; Dickson, B.; Elliott, J.; Hutton, J.; Roe, D.; Vira, B.; Wolmer, W. Biodiversity conservation and the eradication of poverty. Science 2004, 306, 1146–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.M.A.; Pringle, R.M.; Ranganathan, J.; Boggs, C.L.; Chan, Y.L.; Ehrlich, P.R.; Haff, P.K.; Heller, N.E.; Al-Khafaji, K.; Macmynowski, D.P. When agendas collide: Human welfare and biological conservation. Conserv. Biol. 2007, 21, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeely, J.A.; Faith, D.P.; Albers, H.J. Biodiversity, Chapter 5 in Policy Responses. In Part III: Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 1st; Chopra, K., Leemans, R., Eds.; Island Press: Washington, D.C., USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cranford, M.; Mourato, S. Community conservation and a two-stage approach to payments for ecosystem services. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 71, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, S.; Pagiola, S.; Wunder, S. Designing payments for environmental services in theory and practice: An overview of the issues. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 65, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell-Rodwell, C.E.; Rodwell, T.; Rice, M.; Hart, L.A. Living with the modern conservation paradigm: Can agricultural communities co-exist with elephants? A five-year case study in East Caprivi, Namibia. Biol. Conserv. 2000, 93, 381–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, B.H. Conservation and community in the new South Africa: A case study of the Mahushe Shongwe Game Reserve. Geoforum 2007, 38, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanderson, S.E.; Redford, K.H. Contested relationships between biodiversity conservation and poverty alleviation. Oryx 2003, 37, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, B.; Christopher, T. Poverty and biodiversity: measuring the overlap of human poverty and the biodiversity hotspots. Ecol. Econ. 2007, 62, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortwangler, C.L. Social Justice Biodiversity Conservation and Protected Areas. In Contested Nature: Promoting International Biodiversity with Social Justice in the Twenty-First Century, 1st; Brechin, S.R., Wilshusen, P.R., Fortwangler, C.L., West, P.C., Eds.; State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, M. Biodiversity conservation, affluence and poverty: Mismatched costs and benefits and efforts to remedy them. Ambio 1992, 21, 237–243. [Google Scholar]

- Roe, D.; Elliot, J. Poverty reduction and biodiversity conservation: Rebuilding the bridges. Oryx 2004, 38, 137–139. [Google Scholar]

- West, P.; Igoe, J.; Brockington, D. Parks and peoples: The social impact of protected areas. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2006, 35, 251–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudtongkong, C.; Webb, E.L. Outcomes of state vs. community-based mangrove management in southern Thailand. Ecol. Soc. 2008, 13, 27. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature), Beyond Rhetoric: Putting Conservation to Work for the Poor, 1st ed; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2002.

- World Bank, The World Bank Annual Report 2011, 1st ed; World Bank: Washington, D.C., USA, 2011.

- Hartup, B.K. Community conservation in Belize: Demography, resource use, and attitudes of participating landowners. Biol. Conserv. 1994, 69, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, R.J.; Potuku, T.; Montambault, J.R. Community-based conservation results in the recovery of reef fish spawning aggregations in the Coral Triangle. Biol. Conserv. 2011, 144, 1850–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, F. Environmental issues and the role of international Official Development Assistance in Senegal. MSc Dissertation, Instituto Universitario de Desarrollo y Cooperación de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid (IUDC-UCM), Spain, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Caudill, H.; Besseko-Diallo, O. Mido Waawi Pular! Learner’s Guide to Pular (Fuuta Jallon), 2nd ed; Peace Corps: Conakry, Guinea, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Olson, D.M.; Dinerstein, E.; Wikramanayake, E.D.; Burgess, N.D.; Powell, G.V.N.; Underwood, E.C.; D’Amico, J.A.; Itoua, I.; Strand, H.E.; Morrison, J.C.; et al. Terrestrial ecoregions of the world: A new map of life on Earth. BioScience 2001, 51, 933–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USAID (United States Agency for International Development), Étude Socio-Economiques de Dindéfélo, 1st ed; Programme USAID/Wula Nafaa: Kédougou, Senegal, 2011.

- Réserve Naturelle Communautaire de Dindéfélo, RNCD. Plan de Gestion de la Réserve Naturelle Communautaire de Dindéfélo, 1st ed; Institut Jane Goodall Espagne et Programme USAID/Wula Nafaa: Dindéfélo, Senegal, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, J.; Ndiaye, S.; Pruetz, J.; McGrew, W.C. Senegal. In West African Chimpanzees. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan, 1st; Kormos, R., Boesch, C., Bakarr, M.I., Butynski, T., Eds.; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pruetz, J.D.; Marchant, L.M.; Amo, J.; McGrew, W.C. Survey of savanna chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) in Southeastern Sénégal. Am. J. Primatol. 2002, 58, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newmark, W.D.; Hough, J.L. Conserving wildlife in Africa: Integrated conservation and development projects and beyond. BioScience 2000, 50, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struhsaker, T.T.; Struhsaker, P.J.; Siex, K.S. Conserving Africa’s rain forests: Problems in protected areas and possible solutions. Biol. Conserv. 2005, 123, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hockings, K.; Humle, T. Best Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Mitigation of Conflict between Humans and Great Apes, 1st ed; IUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group (PSG): Gland, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Burkill, H.M. The Useful Plants of West Tropical Africa, 2nd ed; Royal Botanic Gardens: Kew, UK, 1994; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- López, G.M. Creación de un Vivero de Saba senegalensis Gestionado por la Asociación de Mujeres de Dindéfélo dentro del Programa de Conservación del Chimpancé Pan troglodytes verus en Senegal y Desarrollo del Ecoturismo Costenible; Project report; University of Alicante: Alicante, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Knutsen, P.G. Threatened existence: Saba senegalensis in southeastern Senegal. MSc Dissertation, Iowa State University, IA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Waller, M. Competition between chimpanzees and humans over fruit of Saba senegalensis in southeastern Senegal. MSc Dissertation, Iowa State University, IA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Arbonnier, M. Arbres, Arbustes et Lianes des Zones Sèches d’Afrique de l’Ouest, 2nd ed; CIRAD: Montpellier, France, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pacheco, L. Table of Wild Plants Eaten by Chimpanzees at RNCD, 1st ed; RNCD: Kédougou, Senegal, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Centre de Suivi Écologique (CSE), Étude Préliminaire: Synthèse des Travaux de Recherche et d’Études sur l’Évaluation Économique ou la Contribution dans la Satisfaction des Besoins des Ménages des Ressources Sauvages au Sénégal, 1st ed; Ministère de l’Environnement et de la Protection de la Nature: Dakar, Senegal, 2005.

- Chacón, M.; Harvey, C.A. Live fences and landscape connectivity in a neotropical agricultural landscape. Agr. Syst. 2006, 68, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocheleau, D.; Weber, F.; Field, A. Agroforestry in Dry-Land Africa, 1st ed; ICRAF: Nairobi, Kenya, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Budowski, G.; Russo, R.O. Live fence posts in Costa Rica: A compilation of the farmer’s beliefs and technologies. J. Sustain. Ag. 1993, 3, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautier, D. The pole cutting practice in the Bamileke country Western Cameroon. Agroforest. Syst. 1995, 31, 21–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, J.F.; Sánchez, R.; Carrete, F.O.; Mena, L. Establishment of different tree species for live fences on the Nayarit coast. Técnica Pecuaria en México 1996, 34, 64–70. [Google Scholar]

- Ayuk, E.T. Adoption of agroforestry technology: The case of live hedges in the central plateau of Burkina Faso. Agr. Syst. 1997, 54, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oteng’i, S.B.B.; Stigter, C.J.; Ng’ang’a, J.K.; Mungai, D.N. Wind protection in a hedged agroforestry system in semiarid Kenya. Agr. Syst. 2000, 50, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, P.R.; Rai, P.; Patnaik, U.S.; Sitaram, R. Live fencing practices in the tribal dominated eastern ghats of India. Agr. Syst. 2004, 63, 111–123. [Google Scholar]

- Levasseur, V.; Olivier, A.; Kaya, B.; Franzel, S. L’Adoption des Haies Vives d’Épineux par les Paysans du Cercle de Ségou au Mali: Le Signe d’Une Société en Mutation? In 2ème Atelier Régional Sur les Aspects Socio-Économiques de l’Agroforesterie au Sahel, Bamako, Mali, 4–6 March 2002.

- Tigere, T.A.; Gatsi, T.C.; Mudita, I.I.; Chikuvire, T.J.; Thamangani, S.; Mavunganidze, Z. Potential of Jatropha curcas in improving smallholder farmers’ livelihoods in Zimbabwe: An exploratory study of Makosa Ward, Mutoko District. J. Sustain. Dev. Af. 2006, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, S.K.; Clifford, S.C.; Popp, M. Ziziphus: A Multipurpose Fruit Tree in Arid Regions. In Sustainable Land-Use in Deserts, 1st; Brecke, S.W., Veste, M., Wucherer, W., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Merijin, B.; Máxime, F.; Rasmus, N.; Brátice, R.; Marta, Z. Why hedgerows? The value of hedgerows for nature and society, and for conventional and organic farmers. Ecological Agriculture University of Copenhagen. Available online: http://www.courseinfo.life.ku.dk/Kurser/LPLF10355/presentation/~/media/Kurser/IJV/250069/biodiversity2004.pdf.ashx (accessed on 10 July 2012).

- Pulido, P.; Renjifo, L.M. Live fences as tools for biodiversity conservation: A study case with birds and plants. Agr. Syst. 2011, 81, 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Estrada, A.; Cammarano, P.L.; Coates, R. Bird species richness in vegetation fences and in strips of residual rain forest vegetation at Los Tuxtlas, Mexico. Biodivers. Conserv. 2000, 9, 1399–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, C.A.; Villanueva, C.; Villacís, J.; Chacón, M.; Muñoz, D.; López, M.; Ibrahim, M.; Gómez, R.; Taylor, R.; Martínez, J.; et al. Contribution of live fences to the ecological integrity of agricultural landscapes in Central America. Agr. Ecosys.t Environ. 2005, 111, 200–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrada, A.; Saenz, J.; Harvey, C.; Naranjo, E.; Muñoz, D.; Rosales, M. Primates in Agroecosystems: Conservation Value of Some Agricultural Practices in Mesoamerican Landscapes. In Study of Mesoamerican Primates: Distribution, Ecology, Behavior and Conservation, 1st; Estrada, A., Garber, P., Pavelka, M., Eds.; Kluwer Academic Publisher: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Tonooka, R. Leaf-folding behavior for drinking water by wild chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes verus) at Bossou, Guinea. Anim. Cogn. 2001, 4, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodfork, J.C. Culture and Customs of the Central African Republic, 1st ed; Greenwood Press: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Skjønsberg, E. Change in an African Village. Kefa Speaks, 1st ed; Kumarian Press: Connecticut, CT, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Raddad, K. Water Resources and Use. In Workshop on Environmental Statistics, Dakar, Senegal, 28 February–4 March 2005; University of Dakar: Dakar, Senegal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Thies, E. Principaux Ligneux Agro-Forestiers de la Guinée. Zone de Transition, 1st ed; Deutsche Geessellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit: Berlin, Germany, 1995. [Google Scholar]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Pacheco, L.; Fraixedas, S.; Fernández-Llamazares, Á.; Estela, N.; Mominee, R.; Guallar, F. Perspectives on Sustainable Resource Conservation in Community Nature Reserves: A Case Study from Senegal. Sustainability 2012, 4, 3158-3179. https://doi.org/10.3390/su4113158

Pacheco L, Fraixedas S, Fernández-Llamazares Á, Estela N, Mominee R, Guallar F. Perspectives on Sustainable Resource Conservation in Community Nature Reserves: A Case Study from Senegal. Sustainability. 2012; 4(11):3158-3179. https://doi.org/10.3390/su4113158

Chicago/Turabian StylePacheco, Liliana, Sara Fraixedas, Álvaro Fernández-Llamazares, Neus Estela, Robert Mominee, and Ferran Guallar. 2012. "Perspectives on Sustainable Resource Conservation in Community Nature Reserves: A Case Study from Senegal" Sustainability 4, no. 11: 3158-3179. https://doi.org/10.3390/su4113158

APA StylePacheco, L., Fraixedas, S., Fernández-Llamazares, Á., Estela, N., Mominee, R., & Guallar, F. (2012). Perspectives on Sustainable Resource Conservation in Community Nature Reserves: A Case Study from Senegal. Sustainability, 4(11), 3158-3179. https://doi.org/10.3390/su4113158