A Novel Green Ocean Strategy for Financial Sustainability (GOSFS) in Higher Education Institutions: King Abdulaziz University as a Case Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Background Information on the New Universities Law in Saudi Arabia

1.2. About King Abdulaziz University (KAU)

1.3. KAU’s Transformation Plan to the New Universities Law

- Achieving the goals of the Kingdom’s Vision 2030;

- Investing the university’s own resources and finding new sources of funding;

- Enhancing the competitive value of the university locally and globally;

- Harmonization of its educational outputs with the labor market;

- Achieving the selection of leaders on the basis of competence;

- Improve operational effectiveness and waste reduction;

- Achieving the optimal investment of human resources in the university.

“How could KAU maximize its investment sources and maintain its financial sustainability?”

2. Literature Review

2.1. Blue Ocean Market Theory Applications in Higher Education

2.2. Green Ocean Market Theory Applications in Higher Education

2.3. Financial Sustainability Applications in Higher Education

3. The Roadmap for Green Ocean Strategy for Financial Sustainability

- Step 1:

- The strategies and resources used to attain financial sustainability differ widely depending on the conditions and goals of each university as well as the characteristics of the community in which the university is located and the forces and influences that shape that community. Due to this, it is important to start the roadmap of GOSFS with a review of successful experiences and practices in the financial sustainability of higher education institutions.

- Step 2:

- The university must create a long-term financial objective for at least 20 years as well as an overall target for the next five years in order to guarantee the continued feasibility of providing its finances. This process involves collaboration between the strategic, academic, and financial professionals from the university administration.

- Step 3:

- As government funding for universities declines, universities increasingly should rely on other funding sources to further their missions and keep the level of education and services they offer. The current sources of the university’s income will be looked at in this step of the roadmap, such as tuition, grants and contracts, endowment, investment income, and others.

- Step 4:

- This step finds the gap between the financial strategic objective set in Step 1 above and the current revenue the university could obtain from the funding sources examined in Step 2. Meetings, brainstorming sessions, forums, and workshops are all different ways to obtain the necessary analysis.

- Step 5:

- Here, the climate for university investment will be studied. In order to improve operations and maximize the use of the university’s resources, this study outlines the most significant investment opportunities, challenges associated with implementing each opportunity, and suggested mechanisms for rationalizing spending and rearranging approved costs and financial liquidity.

- Step 6:

- The sources of the university’s predicted internal financial capacity in several areas, including teaching and learning, scientific research, human capital, and endowments and donations, are positive affirmations of this step. In addition, it is necessary to look at the sources of the university’s external financial capacity, including the university’s expertise in marketing, the expansion of partnerships, and the promotion of community involvement and leadership. Finally, it is advised that this step of the roadmap takes into mind the challenges confronting achieving financial sustainability for the university.

- Step 7:

- Based on the strategic planning approach of Al-Filali [68], formulate the specified objectives for the university’s financial capacity and perform a SWOT analysis for each objective. A patent held by Al-Filali offers a remedy for problems with various systems for strategic planning and performance management. Once overall strategies have been defined, the logic model is employed for the development of details of individual programs, including performance indicators. Here, in this step, instead of conducting the SWOT analysis of the organization followed by the necessary specific objectives, the objectives are created first, then SWOT analysis is conducted for each one.

- Step 8:

- Three interconnected key performance areas (KPAs) serve as the cornerstone of the proposed GOSFS. The first KPA is covered, in this step of the roadmap, under the heading “Resource Development” in a number of pillars that stand in various areas of the financial capacity discovered in Step 6 above. Determine the specific objectives for each pillar and perform a SWOT analysis for each one.

- Step 9:

- This step addresses the second KPA under the heading “Good Governess”, such as restructuring the administrative and financial systems and structuring job grads. Establish the specific objectives associated with this KPA’s foundational principles and conduct a SWOT analysis for each objective.

- Step 10:

- This step relates to the third KPA, “Regulations & Legislation”, which deals with creating systems to promote the internal and external environments as well as creating mechanisms to support environmental sustainability. Determine the specific objectives connected to this KPA’s pillars and conduct a SWOT analysis for each objective.

- Step 11:

- For each KPA listed in Steps 8, 9, and 10 above, create the executive initiatives followed by the business model, balanced scorecard (BSC), and strategy map for each initiative.

- Step 12:

- Here, construct the executive plan for each objective considered in the three KPAs mentioned in Steps 8, 9, and 10. Using performance indicators for each objective, this executive plan demonstrates how each objective should be accomplished.

- Step 13:

- The university’s key administrative entities will obtain the executive plan’s results. Each strategic unit will be given objectives, initiatives, and performance indicators depending on the unit’s primary duties. It is advised that the administrative, academic, educational, and research units must obtain the assignment.

- Step 14:

- The GOSFS is put into action in this step. This implies that each strategic unit must specify the requirements for putting initiatives into action in order to meet performance indicators. Additionally, it must outline the steps for putting each initiative into action, specify the time frame, and the people in charge of each step.

- Step 15:

- This step focuses on the University’s Investment Potential Media Publication (articles, interviews, etc.). It leads to a media communication (MC) plan for the investment options for the university that were mentioned in Step 8 above. It is beneficial to create a database that includes investment opportunities in the university with all its data (classification, location, area, usufruct, nature of usufruct, rental value/allocated, etc.). In addition, preparing an interactive website with an attractive design.

- Step 16:

- Start the GOSFS and MC plans’ follow-up plans. Building relationships and trust with all university units involved in the GOSFS implementation via various communication platforms is crucial to the success of this approach. Without this exchange of information, the plan might not work. Therefore, it is possible to follow up with the strategic units found in Step 14 using visits, emails, reports, automated progress dashboards, and other techniques.

- Step 17:

- Here, calculate the percentage of achievement of each initiative based on the corresponding performance indicators as well as the percentage of achievement from the overall strategic goal of the GOSFS plan that was approved in Step 2.

- Step 18:

- Results from Steps 16 and 17 must be transformed into periodic reports (every three or six months and annually). The reports must detail the accomplishments and challenges that the strategic units faced in achieving the desired percentages, along with suggestions for how to overcome those challenges.

4. An Application of the GOSFS Plan at KAU

4.1. Establishment of Financial Sustainability Office

- Contributing to achieving the Kingdom’s Vision 2030;

- Participating in implementing the New Universities Law to KAU;

- Formulating the KAU’s long- and medium-term financial sustainability plan with clear, comprehensive, and measured performance indicators;

- Proposing the necessary initiatives that achieve the objectives of the financial sustainability plan;

- Following up the accomplishment of the financial sustainability plan at the level of strategic units in the university;

- Strengthening the partnership between the government, private and civil sectors in accordance with Articles 49 and 50 of the New Universities Law;

- Conducting studies and providing consultations in the field of investment and financial sustainability.

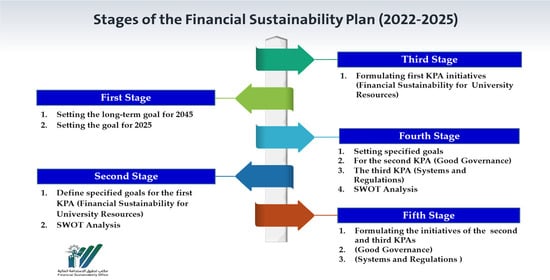

4.2. Stages of the KAU-GOSFS

- Stage #1:

- Setting the main components of KAU’s financial sustainability plan.

- Stage #2:

- Defining the objectives, initiatives, and performance indicators.

- Stage #3:

- Implementing the KAU-GOSFS.

- Stage #4:

- Developing a media communication plan.

- Stage #5:

- Following up and evaluating the achievements.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Restrictions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- National Center for Education Statistics Digest of Education Statistics, Table 317.20. 2021. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d21/tables/dt21_317.20.asp (accessed on 17 February 2023).

- Alqahtani, A.Y.; Rajkhan, A.A. E-learning critical success factors during the COVID-19 pandemic: A comprehensive analysis of e-learning managerial perspectives. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dua, A.; Law, J.; Rounsaville, T.; Viswanath, N. Reimagining Higher Education in the United States. McKinsey & Company. 2020. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/education/our-insights/reimagining-higher-education-in-the-united-states (accessed on 17 February 2023).

- Asomi College of Sciences. An Overview of the Ukrainian-Russian War Effects on the Higher Education Sector. 2020. Available online: https://www.acs-college.com/how-ukraine-war-is-affecting-higher-education (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- Abbass, K.; Begum, H.; Alam, A.F.; Awang, A.H.; Abdelsalam, M.K.; Egdair IM, M.; Wahid, R. Fresh insight through a Keynesian theory approach to investigate the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in Pakistan. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbass, K.; Niazi AA, K.; Qazi, T.F.; Basit, A.; Song, H. The aftermath of COVID-19 pandemic period: Barriers in implementation of social distancing at workplace. Libr. Hi Tech 2022, 40, 569–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbass, K.; Basit, A.; Niazi AA, K.; Mufti, R.; Zahid, N.; Qazi, T.F. Evaluating the social outcomes of COVID-19 pandemic: Empirical evidence from Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, H.; Abbas, K.; Alam, A.F.; Song, H.; Chowdhury, M.T.; Abdul Ghani, A.B. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the environment and socioeconomic viability: A sustainable production chain alternative. Foresight 2022, 24, 456–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Abbass, K.; Niazi AA, K.; Zhang, H.; Basit, A.; Qazi, T.F. Assessment of sustainable green financial environment: The underlying structure of monetary seismic aftershocks of the COVID-19 pandemic. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Q.M.; Nisar, Q.A.; Abidin RZ, U.; Qammar, R.; Abbass, K. Greening the workforce in higher educational institutions: The pursuance of environmental performance. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbass, K.; Asif, M.; Niazi AA, K.; Qazi, T.F.; Basit, A.; Al-Muwaffaq Ahmed, F.A. Understanding the interaction among enablers of quality enhancement of higher business education in Pakistan. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuf, N.; Jamjoom, Y. The Role of Higher Education Institutions in Developing Employability Skills of Saudi Graduates Amidst Saudi 2030 Vision. Eur. J. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 11, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-khateeb, B.A.A. Technological Skills and Job Employment in Universities in Saudi Arabia. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Opportunities and Challenges in Management, Economics, and Accounting, Milan, Italy, 18–20 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Makhlouf, A.M.E.S. Saudi Schools’ Openness to Change in Light of the 2030 Vision. Am. J. Educ. Res. 2021, 9, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, A. Higher Education in KSA: Changing Demand in Line with Vision 2030. 2022. Available online: https://www.colliers.com/en-ae/research/overview-of-higher-education-market-in-ksa (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- Vision2030. Saudi Vision Official Website. 2022. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Nurunnabi, M. Transformation from an oil-based economy to a knowledge-based economy in Saudi Arabia: The direction of Saudi vision 2030. J. Knowl. Econ. 2017, 8, 536–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aburizaizah, S.J. The role of quality assurance in Saudi higher education institutions. Int. J. Educ. Res. Open 2022, 3, 100127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, A.; Makki, A.; Abdulaal, R. A proposed NCAAA-based approach to the self-evaluation of higher education programs for academic accreditation: A comparative study using TOPSIS. Decis. Sci. Lett. 2023, 12, 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albeshir, S.G. A Comparative study between the new and old university laws in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Res. 2022, 10, 148–157. [Google Scholar]

- University’s Regulation. The Law of Universities Rendered by the Royal Decree No. M/27 Dated 02/03/1441H, First Edition. 2022. Available online: https://units.imamu.edu.sa/colleges/en/LanguageAndTranslation/FilesLibrary/Documents/Universities%20Regulation.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Ozili, P.K. Theories of sustainable finance. Manag. Glob. Transit. 2022, 22, 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansoff, H.I.; Kipley, D.; Lewis, A.O.; Helm-Stevens, R.; Ansoff, R. Implanting Strategic Management, 3rd ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, W.C.; Mauborgne, R. Red ocean traps. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2015, 93, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Aithal, P.S. ABCD Analysis of Red Ocean Strategy. National Conference on Changing Perspectives of Management, IT and Social Sciences in the Contemporary Environment; SIMS: Mangalore, India, 2016; ISBN 978-93-5265-653-0. [Google Scholar]

- Raman, R.V. Comparison between ocean strategies. Int. J. Core Eng. Manag. 2014, 1, 44–58. [Google Scholar]

- Shafiq, M.; Tasmin, R.; Qureshi, M.I.; Takala, J. A new framework of blue ocean strategy for innovation performance in manufacturing sector. Int. J. Eng. Adv. Technol. 2019, 8, 1382–1389. [Google Scholar]

- Yunus, M.; Sijabat, F.N. A Review on Blue Ocean Strategy Effect on Competitive Advantage and Firm Performance. Acad. Strateg. Manag. J. 2021, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Adrian, D.T.; Silviu, M. The Green Ocean Innovation Model. Int. J. Bus. Humanit. Technol. 2013, 3, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Asj’Ari, F.; Subandowo, M.; Bagus, I.M. The application of green economy to enhance performance of creative industries through the implementation of blue ocean strategy: A case study on the creative industries. Russ. J. Agric. Socio-Econ. Sci. 2018, 83, 361–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, B.; Sheng, F.; Gao, Y.; Tsai, S.B.; Du, X. “Green Ocean Treasure Hunting” Guided by Policy Support in a Transitional Economy. Sustainability 2018, 10, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaa AG, A. The Role of the Green Ocean Strategy in Mediating Stimulating Continuous Innovation to Achieve Strategy Victory: An Exploratory Study in the General Company for Leather Industries. Int. J. Transform. Bus. Manag. 2022, 12, 132–149. [Google Scholar]

- Aithal, P.S.; Kumar, P.M. Black Ocean Strategy-A Probe into a new type of Strategy used for Organizational Success. GE-Int. J. Manag. Res. (GE-IJMR) 2015, 3, 45–65. [Google Scholar]

- Aithal, P.S. The concept of ideal strategy and its realization using white ocean mixed strategy. Int. J. Manag. Sci. Bus. Res. 2016, 5, 171–179. [Google Scholar]

- Scarlat, C.; Panduru, D.A. The Purple Ocean: Revisiting the Blue Ocean Strategy. J. East. Eur. Res. Bus. Econ. 2021, 2021, 165416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markopoulos, E.; Ramonda, M.B.; Winter LM, C.; Al Katheeri, H.; Vanharanta, H. Pink Ocean Strategy: Democratizing Business Knowledge for Social Growth and Innovation. In Advances in Creativity, Innovation, Entrepreneurship and Communication of Design, Proceedings of the AHFE 2020 Virtual Conferences on Creativity, Innovation and Entrepreneurship, and Human Factors in Communication of Design, USA, 16–20 July 2020; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 39–51. [Google Scholar]

- Sanders, S.; Chapman, M.; Parker, J. Achieving Financial Sustainability in Higher Education. 2018. Available online: https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/uk/pdf/2018/10/achieving-financial-sustainability-in-higher-education.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2023).

- Hinton, K.E. A Practical Guide to Strategic Planning in Higher Education; Society for College and University Planning: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2012; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Tromp, S.A.; Ruben, B.D. Strategic Planning in Higher Education: A Guide for Leaders, 2nd ed.; National Association of College and University Business Officers: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, G.; Fischer, M. Strategic Planning in Public Higher Education: Management Tool or Publicity Platform? Educ. Plan. 2015, 22, 5–17. [Google Scholar]

- Syed Hassan, S.A.H.; Tan, S.C.; Yusof, K.M. MCDM for Engineering Education: Literature Review and Research Issues. In Engineering Education for a Smart Society; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 204–214. [Google Scholar]

- Strike, T. (Ed.) Higher Education Strategy and Planning: A Professional Guide, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Braganca, R. Blue Ocean Strategy for Higher Education. In Proceedings of the International Conferences on Internet Technologies & Society (ITS 2016), Educational Technologies (ICEduTech 2016), and Sustainability, Technology and Education (STE 2016), Melbourne, Australia, 6–8 December 2016; pp. 325–328. [Google Scholar]

- Aguirre Fernández Bravo, E.; Guindal Pintado, M.D. Entrepreneurship in interpreting: A blue ocean strategy didactic toolkit for Higher Education Interpreter Training. J. Lang. Commun. Bus. 2020, 60, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazmira, M.; Wicaksono, A. Blue Ocean Strategy as A Solution to New Entrants in Higher Educational Industry. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Management in Emerging Markets, Bandung, Indonesia, 11–13 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Abdalla, A. A proposed strategic vision for developing postgraduate educational studies in Egyptian universities in light of the blue ocean strategy to achieve competitive advantage. J. Sci. Res. Educ. 2021, 22, 1–65. [Google Scholar]

- Abbass, K.; Song, H.; Mushtaq, Z.; Khan, F. Does technology innovation matter for environmental pollution? Testing the pollution halo/haven hypothesis for Asian countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 89753–89771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbass, K.; Song, H.; Khan, F.; Begum, H.; Asif, M. Fresh insight through the VAR approach to investigate the effects of fiscal policy on environmental pollution in Pakistan. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 23001–23014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbass, K.; Qasim, M.Z.; Song, H.; Murshed, M.; Mahmood, H.; Younis, I. A review of the global climate change impacts, adaptation, and sustainable mitigation measures. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 42539–42559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjad, A.; Abbass, K.; Hussain, Y.; Khan, F.; Sadiq, S. Effects of the green supply chain management practices on firm performance and sustainable development. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 66622–66639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Y.; Abbass, K.; Usman, M.; Rehan, M.; Asif, M. Exploring the mediating role of environmental strategy, green innovations, and transformational leadership: The impact of corporate social responsibility on environmental performance. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 76864–76880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smyth, D.P.; Fredeen, A.L.; Booth, A.L. Reducing solid waste in higher education: The first step towards ‘greening’ a university campus. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2010, 54, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aithal, P.S.; Rao, P. Green education concepts & strategies in higher education model. Int. J. Sci. Res. Mod. Educ. IJSRME ISSN Online 2016, 1, 793–802. [Google Scholar]

- Abeyrathna, A.W.G.N.M. Green Education in a University Classroom: Benefits and Challenges. In Proceedings of the 7th International Research Conference on Humanities & Social Sciences (IRCHSS), Sri Lanka, South Africa, 18–19 March 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Abu-Eisheh, S.; Hijazi, I. Strategic Planning for the Transformation of a University Campus Towards Smart, Eco and Green Sustainable Built Environment: A Case Study from Palestine. In Proceedings of the Sustainable Built Environment (SBE) Regional Conference, Zurich, Switzerland, 15–17 June 2016; pp. 148–153. [Google Scholar]

- Sisriany, S.; Fatimah, I.S. Green Campus Study by Using 10 UNEP’s Green University Toolkit Criteria in IPB Dramaga Campus. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2017; Volume 91, p. 012037. [Google Scholar]

- Leal Filho, W.; Will, M.; Salvia, A.L.; Adomssent, M.; Grahl, A.; Spira, F. The role of green and Sustainability Offices in fostering sustainability efforts at higher education institutions. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 1394–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tariq, F.; Ahmed, M.; Usman, M. Green Initiatives of Higher Education Institutions (HEIS) and Students’ Willingness to Participate in Green Activities: A Asudy in Pakistan. Int. J. Bus. Reflect. 2021, 2, 158–180. [Google Scholar]

- Afriyie, A.O. Financial sustainability factors of higher education institutions: A predictive model. Int. J. Educ. Learn. Dev. 2015, 2, 17–38. [Google Scholar]

- Sazonov, S.P.; Kharlamova, E.E.; Chekhovskaya, I.A.; Polyanskaya, E.A. Evaluating financial sustainability of higher education institutions. Asian Soc. Sci. 2015, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernostana, Z. Financial Sustainability for Private Higher Education Institutions. Institute of Economic Research (IER): Toruń Poland Working Papers (No. 17/2017). , 2017. Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/peswpaper/2017_3ano17.htm (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Kuzmina, J. Financial Sustainability of Higher Education Institutions. Society. Integr. Educ. Proc. Int. Sci. Conf. 2021, 6, 324–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieler, A.; McKenzie, M. Strategic planning for sustainability in Canadian higher education. Sustainability 2017, 9, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almagtome, A.; Shaker, A.; Al-Fatlawi, Q.; Bekheet, H. The integration between financial sustainability and accountability in higher education institutions: An exploratory case study. Integration 2019, 8, 202–221. [Google Scholar]

- Montenegro de Lima, C.R.; Coelho Soares, T.; Andrade de Lima, M.; Oliveira Veras, M.; Andrade Guerra JB SO, D.A. Sustainability funding in higher education: A literature-based review. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2020, 21, 441–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vision2030. Fiscal Sustainability Program. 2022. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/v2030/vrps/fsp/ (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Vision2030. Privatization Program. 2022. Available online: https://www.vision2030.gov.sa/v2030/vrps/privatization/ (accessed on 17 January 2023).

- Al-Filali, I.Y. Reyada System and Method for Performance Management, Communication, Strategic Planning, and Strategy Execution. US Patent US 11,100,446 B2, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- King Abdulaziz University. KAU’s Strategic Plans. 2023. Available online: https://vp-development.kau.edu.sa/Default-351-EN (accessed on 20 February 2023).

- Sharaf-Addin, H.H.; Fazel, H. Balanced Scorecard Development as a Performance Management System in Saudi Public Universities: A Case Study Approach. Asia-Pac. J. Manag. Res. Innov. 2021, 17, 57–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cardeal, G.; Höse, K.; Ribeiro, I.; Götze, U. Sustainable business models—Canvas for sustainability, evaluation method, and their application to additive manufacturing in aircraft maintenance. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, S.M. Business Model: Literature Review. Pinisi Discrition Rev. 2021, 4, 191–196. [Google Scholar]

| Event #1 (20 October 2020)—60 participants “Developing the Investment Environment at KAU” | |

| Session #1: |

|

| Session #2: |

|

| Event #2 (2 December 2020)—33 participants “The First Financial Sustainability Forum in Light of the New Universities Law” | |

| Session #1: |

|

| Session #2: |

|

| Event #3 (15 March 2021)—71 participants “The Second Financial Sustainability Forum in Light of the New Universities Law” | |

| Session #1: |

|

| Session #2: |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Filali, I.Y.; Abdulaal, R.M.S.; Melaibari, A.A. A Novel Green Ocean Strategy for Financial Sustainability (GOSFS) in Higher Education Institutions: King Abdulaziz University as a Case Study. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7246. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097246

Al-Filali IY, Abdulaal RMS, Melaibari AA. A Novel Green Ocean Strategy for Financial Sustainability (GOSFS) in Higher Education Institutions: King Abdulaziz University as a Case Study. Sustainability. 2023; 15(9):7246. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097246

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Filali, Isam Y., Reda M. S. Abdulaal, and Ammar A. Melaibari. 2023. "A Novel Green Ocean Strategy for Financial Sustainability (GOSFS) in Higher Education Institutions: King Abdulaziz University as a Case Study" Sustainability 15, no. 9: 7246. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15097246