Urban in Question: Recovering the Concept of Urban in Urban Resilience

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature: Urban Concepts

2.1. Urban as a Subject of Study

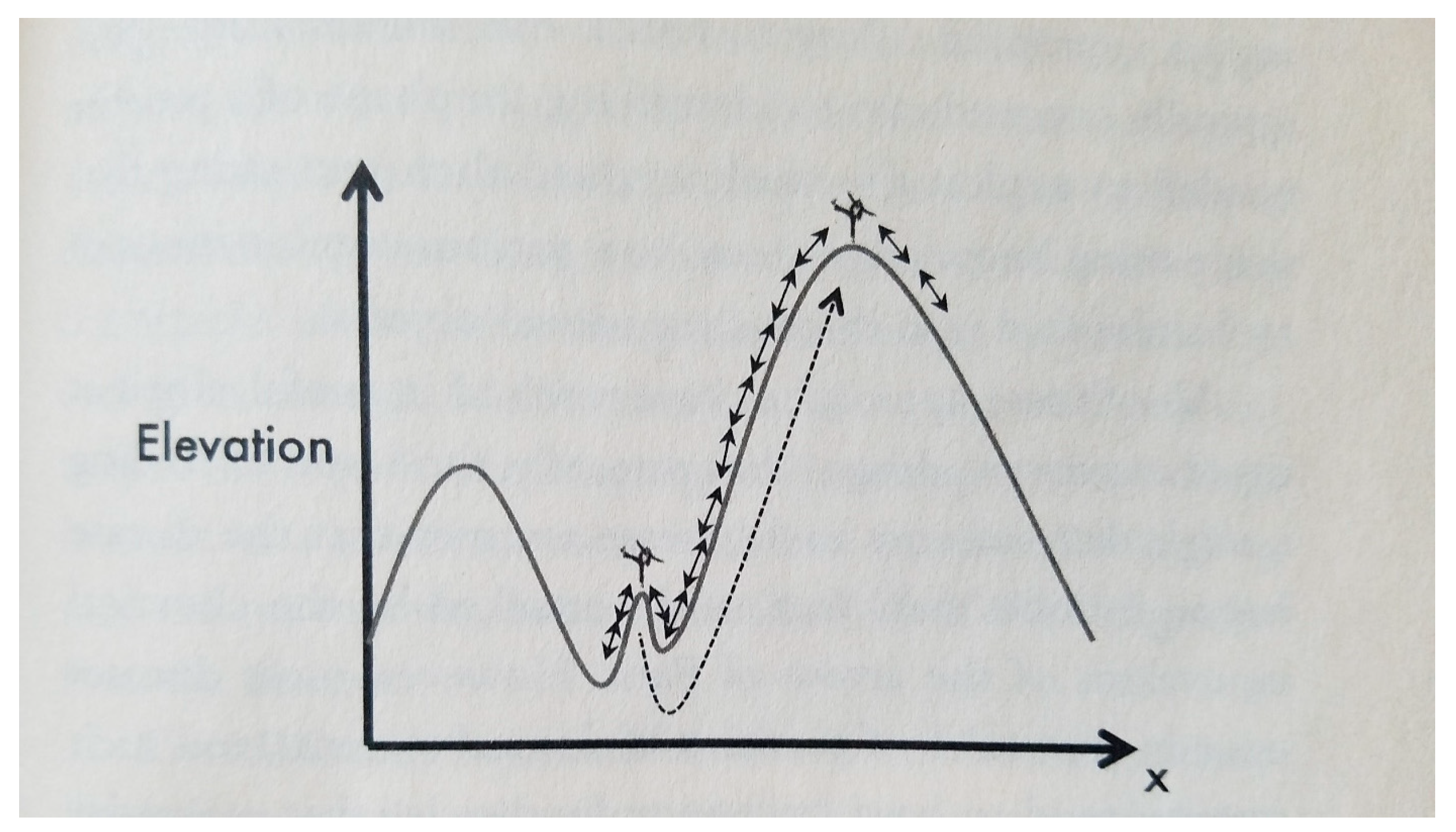

2.2. Urban as a Condition

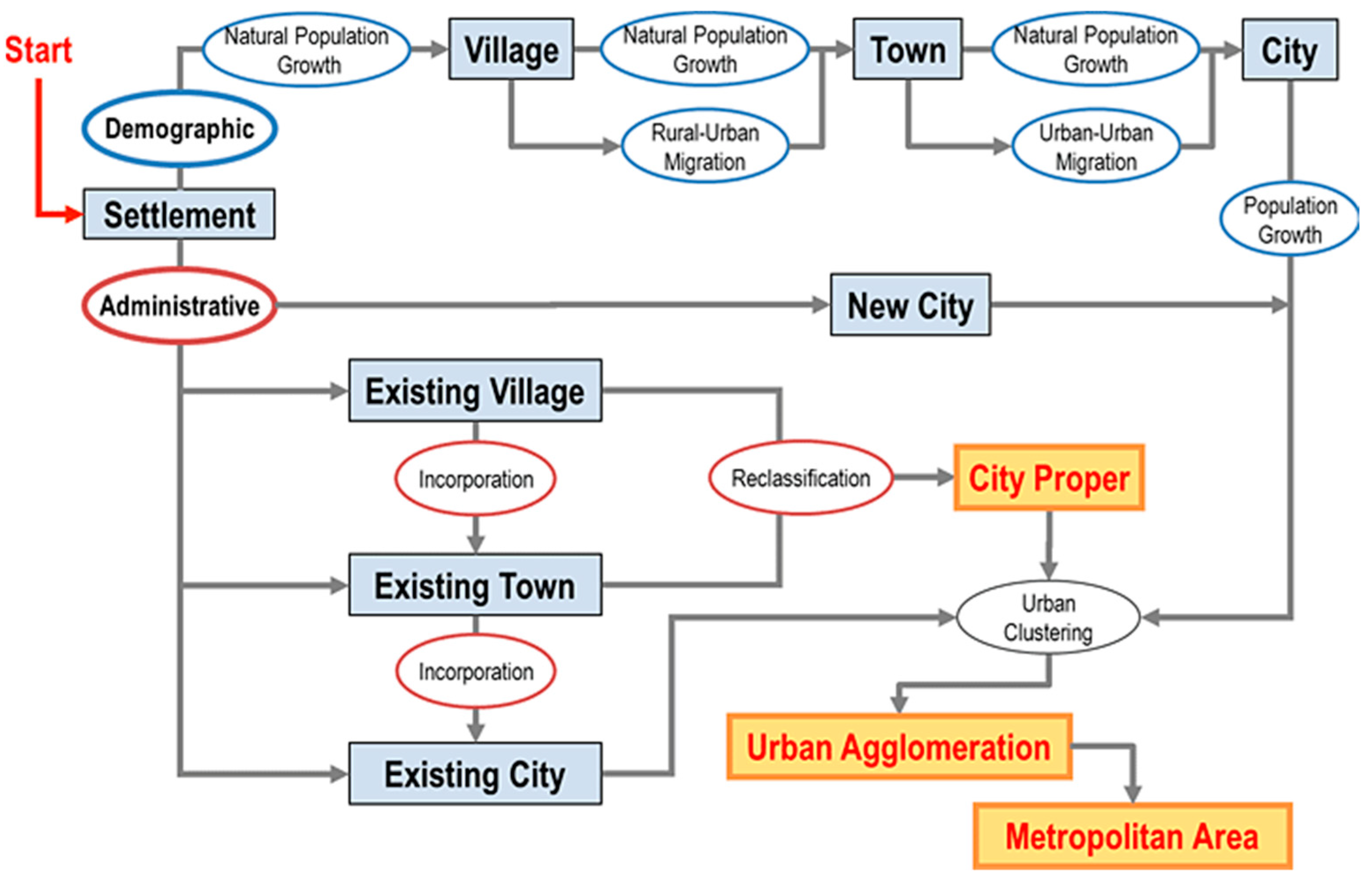

2.3. Urban as a Measurement Category

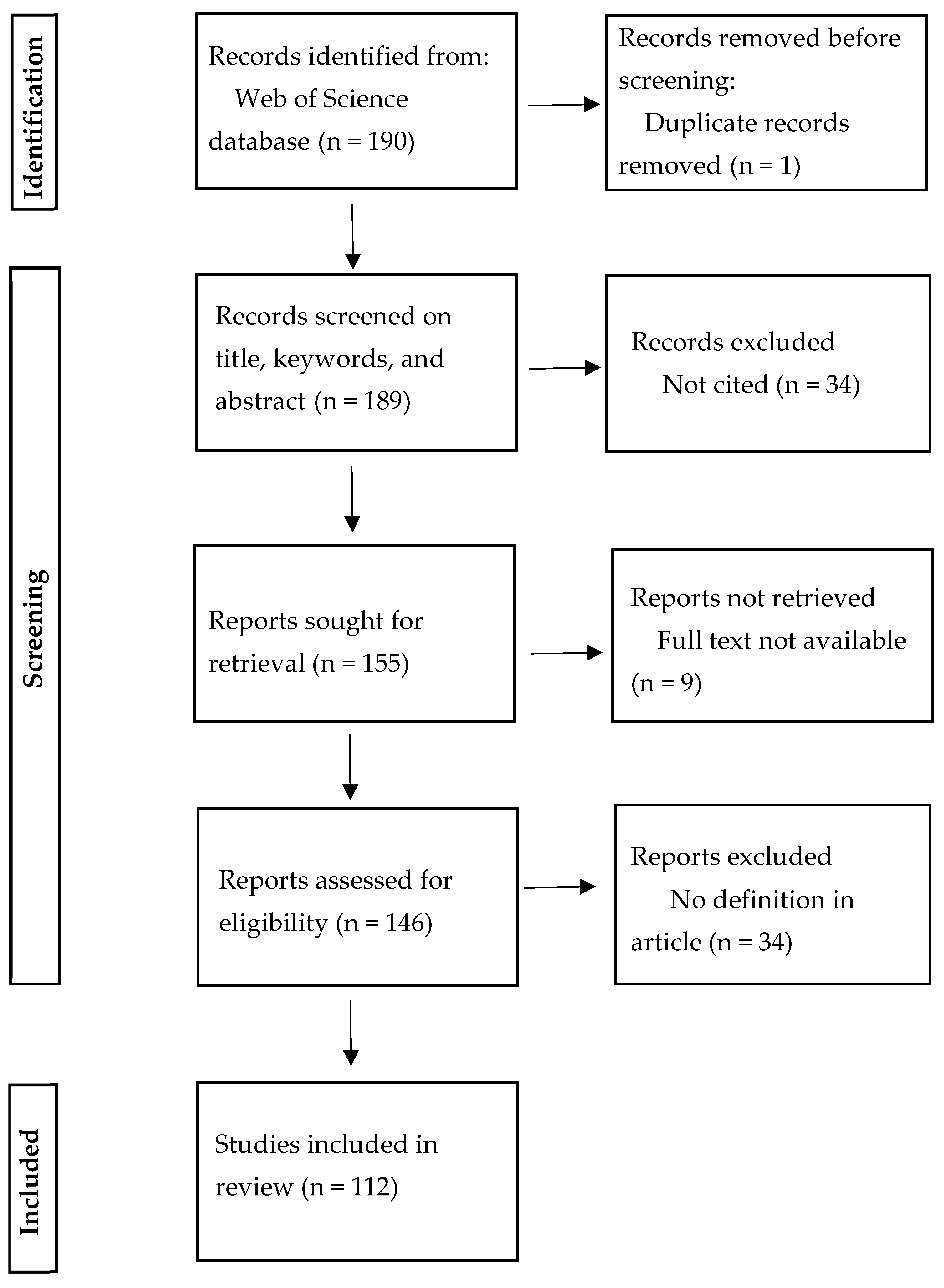

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Reviews of Prior Literature

4.2. Frameworks or Models

4.3. Empirical Studies

5. Discussion

5.1. Questions about Urban

5.2. Applying Urban Concepts

5.3. Urban Reconsidered

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Authors and Year | Proposed Definition |

|---|---|

| [18] | “Urban resilience refers to the ability of an urban system—and all its constituent socio-ecological and socio-technical networks across temporal and spatial scales—to maintain or rapidly return to desired functions in the face of a disturbance, to adapt to change, and to quickly transform systems that limit current or future adaptive capacity” (p. 39). |

| [63] | Urban resilience is “the capacity of a city and its urban systems (social, economic, natural, human, technical, physical) to absorb the first damage, to reduce the impacts (changes, tensions, destruction or uncertainty) from a disturbance (shock, natural disaster, changing weather, disasters, crises or disruptive events), to adapt to change and to systems that limit current or future adaptive capacity” (p. 4). |

| [88] | Urban resilience is “[t]he capacity of an urban system to absorb disturbance, reorganize, maintain essentially the same functions and feedbacks over time and continue to develop along a particular trajectory. This capacity stems from the character, diversity, redundancies and interactions among and between the components involved in generating different functions. Resilience is fundamentally non-normative and an attribute of the system and applicable to different subsystems” (p. 269). |

| [93] | Urban resilience is “the passive process of monitoring, facilitating, maintaining and recovering a virtual cycle between ecosystem services and human wellbeing through concerted effort under external influencing factors” (p. 145). |

| [101] | Urban resilience is “the capacity of individuals, communities, institutions, businesses, and systems within a city to survive, adapt, and grow regardless of the kinds of chronic stress and acute shocks they experience” (p. 110). |

References

- Leichenko, R. Climate change and urban resilience. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2011, 3, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimellaro, G.P. Urban Resilience for Emergency Response and Recovery; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Coaffee, J.; Lee, P. Urban Resilience: Planning for Risk, Crisis and Uncertainty; Palgrave: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Godschalk, D.R. Urban hazard mitigation: Creating resilient cities. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2003, 4, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanella, T.J. Urban resilience and the recovery of New Orleans. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 2006, 72, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabareen, Y. Planning the resilient city: Concepts and strategies for coping with climate change and environmental risk. Cities 2013, 31, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, A. Of resilient places: Planning for urban resilience. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2016, 24, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, H.; Sheppard, E.; Webber, S.; Colven, E. Globalizing urban resilience. Urban Geogr. 2018, 39, 1276–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beilin, R.; Wilkinson, C. Introduction: Governing for urban resilience. Urban Stud. 2015, 52, 1205–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, C.; Blackburn, S. Advocacy for urban resilience: UNISDR’s making cities resilient campaign. Environ. Urban. 2014, 26, 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normandin, J.; Therrien, M.; Pelling, M.; Paterson, S. The definition of urban resilience: A transformation path towards collaborative urban risk governance. In Urban Resilience for Risk and Adaptation Governance; Brunetta, G., Caldarice, O., Tollin, N., Rosas-Casals, M., Morató, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 9–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rockefeller Foundation. City Resilience Framework—100 Resilient Cities; Rockefeller Foundation: New York, NY, USA, 2014; 5p. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Sendai Framework on Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030; U.N. Office for Disaster Risk Reduction: New York, NY, USA, 2015; 32p. [Google Scholar]

- Weichselgartner, J.; Kelman, I. Geographies of resilience: Challenges and opportunities of a descriptive concept. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2015, 39, 249–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. Investing in Urban Resilience: Protecting and Promoting Development in a Changing World; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2016; 120p. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter, S.; Walker, B.; Anderies, J.; Abel, N. From metaphor to measurement: Resilience of what to what? Ecosystems 2001, 4, 765–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davoudi, S. Resilience: A bridging concept or a dead end? Plan. Theory Pract. 2012, 13, 299–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P.; Stults, M. Defining urban resilience: A review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 147, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzo, B. Problematizing resilience: Implications for planning theory and practice. Cities 2015, 43, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vale, L.J. The politics of resilient cities: Whose resilience and whose city? Build. Res. Inf. 2014, 42, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brueckner, J.K. Lectures on Urban Economics; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, E.S. Urban Economics; Scott Foresman & Co: Glenview, IL, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sullivan, A. Urban Economics; Irwin: Chicago, IL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, A.; Storper, M. The nature of cities: The scope and limits of urban theory. Int. J. Urban Reg. 2015, 39, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duranton, G.; Puga, D. Micro-foundations of urban agglomeration economies. In Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics; Henderson, V., Thisse, J.F., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; Volume 4, pp. 2063–2117. [Google Scholar]

- Fujita, M.; Thisse, J.F. Economics of agglomeration. J. Jpn. Int. Econ. 1996, 10, 339–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, A. Principles of Economics; MacMillan: London, UK, 1920. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, J. Ordinary Cities: Between Modernity and Development; Routledge: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, A. Slumdog cities: Rethinking subaltern urbanism. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2011, 35, 223–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, A. Who’s afraid of postcolonial theory? Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2016, 40, 200–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, J. Global and world cities: A view from off the map. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2002, 26, 531–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lefebvre, H. The Urban Revolution; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, N. What is critical urban theory? City 2009, 13, 198–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, N.; Schmid, C. The ‘Urban Age’ in question. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2014, 38, 731–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells, M. Y a-t-il une sociologie urbaine? Sociol. Travel. 1968, 10, 72–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, N. Forward. In The Urban Revolution; Lefebre, H., Ed.; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wirth, L. Urbanism as a way of life. Am. J. Sociol. 1938, 44, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmel, G. The Metropolis and Mental Life. In The Sociology of Georg Simmel; Gerth, H.H.; Wright Mills, C., Translators; Wolff, K., Ed.; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1903. [Google Scholar]

- Woolston, H.B. The urban habit of mind. Am. J. Sociol. 1912, 17, 602–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, R. The rural-urban continuum: Real but relatively unimportant. Am. J. Sociol. 1960, 66, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiss, A. An analysis of urban phenomena. In The Metropolis in Modern Life; Fisher, R., Ed.; Doubleday: New York, NY, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, M. The Urban Question: A Marxist Approach; Edward Arnold Publishing: London, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Consciousness and the Urban Experience: Studies in the History and Theory of Capitalist Urbanization; Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. Spaces of Hope; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Abbott, A. Of time and space: The contemporary relevance of the Chicago School. Soc. Forces 1997, 75, 1149–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boggs, S.L. Urban crime patterns. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1965, 30, 899–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satterthwaite, D. Urban poverty: Reconsidering its scale and nature. IDS Bull. 1997, 28, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straszheim, M.R. Estimation of the demand for urban housing services from household interview data. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1973, 55, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldinger, R. Immigration and urban change. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1989, 15, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Redefining “Urban”: A New Way to Measure Metropolitan Areas; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 2018 Revision of the world urbanization prospects. In Department of Economic and Social Affairs; Population Dynamics: New York, NY, USA, 2018; 126p. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2010 Census Urban and Rural Classification and Urban Area Criteria; Department of Commerce: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Potts, D. Conflict and collisions in sub-Saharan African urban definitions: Interpreting recent urbanization data from Kenya. World Dev. 2017, 97, 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Census Bureau. How Do Households Describe Where They Live? Department of Commerce: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Satterthwaite, D. Urban Myths and the Misuse of Data that Underpin Them; UNU-WIDER Working Paper, No. 2010/28; World Institute for Development Economics Research: Helsinki, Finland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2001 Revision; Publication ST/ESA/SER.A/216; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2002; 190p. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, P.M. Cities and Regions as Self-organizing Systems: Models of Complexity; Gordon and Breach: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Batty, M. The size, scale, and shape of cities. Science 2008, 319, 769–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batty, M.; Xie, Y. From cells to cities. Environ. Plan. B 1994, 21, S31–S48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eidelson, R.J. Complex adaptive systems in the behavioral and social sciences. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 1997, 1, 42–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, J.H. Complex adaptive systems. Daedalus 1992, 121, 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, S.; Xepapadeas, T.; Crépin, A.-S.; Norberg, J.; de Zeeuw, A.; Folke, C.; Hughes, T.; Arrow, K.; Barrett, S.; Daily, G.; et al. Social-ecological systems as complex adaptive systems: Modeling and policy implications. Environ. Dev. Econ. 2013, 18, 111–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, P.J.G.; Gonçalves, L.A.P.J. Urban resilience: A conceptual framework. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 50, 101625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Humaiqani, M.M.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. The built environment resilience qualities to climate change impact: Concepts, frameworks, and directions for future research. Sustain. Cities. Soc. 2022, 80, 103797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assarkhaniki, Z.; Rajabifard, A.; Sabri, S. The conceptualisation of resilience dimensions and comprehensive quantification of the associated indicators: A systematic approach. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2020, 51, 101840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayub, B.; Naderpajouh, N.; Boukamp, F.; McGough, T. Housing market bubbles and urban resilience: Applying systems theory. Cities 2020, 106, 102925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blečić, I.; Cecchini, A. Antifragile planning. Plan. Theor. 2020, 19, 172–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozza, A.; Asprone, D.; Fabbrocino, F. Urban resilience: A civil engineering perspective. Sustainability 2017, 9, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyüközkan, G.; Ilıcak, Ö.; Feyzioğlu, O. A review of urban resilience literature. Sustain Cities Soc. 2022, 77, 103579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capolongo, S.; Rebecchi, A.; Dettori, M.; Appolloni, L.; Azara, A.; Buffoli, M.; Capasso, L.; Casuccio, A.; Conti, G.O.; D’amico, A.; et al. Healthy design and urban planning strategies, actions, and policy to achieve salutogenic cities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Corte, V.; Del Gaudio, G.; Sepe, F.; Luongo, S. Destination resilience and innovation for advanced sustainable tourism management: A bibliometric analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gernay, T.; Selamet, S.; Tondini, N.; Khorasani, N.E. Urban infrastructure resilience to fire disaster: An overview. Procedia Eng. 2016, 161, 1801–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huff, E.S.; Johnson, M.L.; Roman, L.A.; Sonti, N.F.; Pregitzer, C.C.; Campbell, L.K.; McMillen, H. A literature review of resilience in urban forestry. Arboric. Urban For. 2020, 46, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iturriza, M.; Hernantes, J.; Abdelgawad, A.A.; Labaka, L. Are cities aware enough? A framework for developing city awareness to climate change. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iturriza, M.; Labaka, L.; Hernantes, J.; Abdelgawad, A. Shifting to climate change aware cities to facilitate the city resilience implementation. Cities 2020, 101, 102688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iturriza, M.; Labaka, L.; Ormazabal, M.; Borges, M. Awareness-development in the context of climate change resilience. Urban Clim. 2020, 32, 100613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, D.; Kilar, V.; Rus, K. Proposal for holistic assessment of urban system resilience to natural disasters. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 245, 062011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurth, M.H.; Keenan, J.M.; Sasani, M.; Linkov, I. Defining resilience for the US building industry. Build. Res. Inf. 2019, 47, 480–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClymont, K.; Morrison, D.; Beevers, L.; Carmen, E. Flood resilience: A systematic review. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 63, 1151–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Stults, M. Comparing conceptualizations of urban climate resilience in theory and practice. Sustainability 2016, 8, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moglia, M.; Frantzeskaki, N.; Newton, P.; Pineda-Pinto, M.; Witheridge, J.; Cook, S.; Glackin, S. Accelerating a green recovery of cities: Lessons from a scoping review and a proposal for mission-oriented recovery towards post-pandemic urban resilience. Dev. Built Environ. 2021, 7, 100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya, J.; Goenechea, M. An approach to the unified conceptualization, definition, and characterization of social resilience. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 5746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.L.; Akerkar, R. Modelling, measuring, and visualising community resilience: A systematic review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parizi, S.M.; Taleai, M.; Sharifi, A. Integrated methods to determine urban physical resilience characteristics and their interactions. Nat. Hazards 2021, 109, 725–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodina, L. Defining “water resilience”: Debates, concepts, approaches, and gaps. WIREs Water 2019, 6, e1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urquiza, A.; Amigo, C.; Billi, M.; Calvo, R.; Gallardo, L.; Neira, C.I.; Rojas, M. An integrated framework to streamline resilience in the context of urban climate risk assessment. Earths Future 2021, 9, e2020EF001508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Xue, X.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, X. Exploring the emerging evolution trends of urban resilience research by scientometric analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15, 2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmqvist, T.; Andersson, E.; Frantzeskaki, N.; McPhearson, T.; Olsson, P.; Gaffney, O.; Takeuchi, K.; Folke, C. Sustainability and resilience for transformation in the urban century. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahern, J. From fail-safe to safe-to-fail: Sustainability and resilience in the new urban world. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2011, 100, 341–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coaffee, J.; Therrien, M.; Chelleri, L.; Henstra, D.; Aldrich, D.P.; Mitchell, C.L.; Tsenkova, S.; Rigaud, E.; on behalf of the participants. Urban resilience implementation: A policy challenge and research agenda for the 21st century. J. Contingencies Crisis Manag. 2018, 26, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelleri, L.; Waters, J.J.; Olazabal, M.; Minucci, G. Resilience trade-offs: Addressing multiple scales and temporal aspects of urban resilience. Environ. Urban. 2015, 27, 181–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, T.K.; Khirfan, L. A multi-scale and multi-dimensional framework for enhancing the resilience of urban form to climate change. Urban Clim. 2017, 19, 72–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, H. Urban resilience and urban sustainability: What we know and what do not know? Cities 2018, 72, 141–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bristow, D.N.; Mohareb, E.A. From the urban metabolism to the urban immune system. J. Ind. Ecol. 2020, 24, 300–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastjerdi, M.S.; Lak, A.; Ghaffari, A.; Sharifi, A. A conceptual framework for resilient place assessment based on spatial resilience approach: An integrative review. Urban Clim. 2021, 36, 100794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keen, M.; Connell, J. Regionalism and resilience? Meeting urban challenges in Pacific Island states. Urban Policy Res. 2019, 37, 324–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, T.M.; Guikema, S.D. Reframing resilience: Equitable access to essential services. Risk Anal. 2020, 40, 1538–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottenburger, S.S.; Çakmak, H.K.; Jakob, W.; Blattmann, A.; Trybushnyi, D.; Raskob, W.; Kühnapfel, U.; Hagenmeyer, V. A novel optimization method for urban resilient and fair power distribution preventing critical network states. Int. J. Crit. Infr. Prot. 2020, 29, 100354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwind, N.; Minami, K.; Maruyama, H.; Ilmola, L.; Inoue, K. Computational framework of resilience. In Urban Resilience: A Transformative Approach; Yamagata, Y., Maruyama, H., Eds.; Springer Cham: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 239–257. [Google Scholar]

- Shamsuddin, S. Resilience resistance: The challenges and implications of urban resilience implementation. Cities 2020, 103, 102763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaans, M.; Waterhout, B. Building up resilience in cities worldwide—Rotterdam as participant in the 100 Resilient Cities Programme. Cities 2017, 61, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Barajas, I.; Sisto, N.P.; Ramirez, A.I.; Magaña-Rueda, V. Building urban resilience and knowledge co-production in the face of weather hazards: Flash floods in the Monterrey Metropolitan Area (Mexico). Environ. Sci. Policy 2019, 99, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito Del Pozo, P.; López-González, A. Urban resilience and the alternative economy: A methodological approach applied to Northern Spain. Geogr. Rev. 2020, 110, 322–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoni, A.; Borlera, S.L.; Malandrino, F.; Cimellaro, G.P. Seismic vulnerability and resilience assessment of urban telecommunication networks. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 77, 103540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errigo, M.F. The Adapting city. Resilience through water design in Rotterdam. TeMA J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2018, 11, 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, L.; Debucquoy, W.; Anguelovski, I. The influence of urban development dynamics on community resilience practice in New York City after Superstorm Sandy: Experiences from the Lower East Side and the Rockaways. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2016, 40, 112–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handayani, W.; Fisher, M.R.; Rudiarto, I.; Setyono, J.S.; Foley, D. Operationalizing resilience: A content analysis of flood disaster planning in two coastal cities in Central Java, Indonesia. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2019, 35, 101073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huck, A.; Monstadt, J.; Driessen, P. Building urban and infrastructure resilience through connectivity: An institutional perspective on disaster risk management in Christchurch, New Zealand. Cities 2020, 98, 102573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monstadt, J.; Schmidt, M. Urban resilience in the making? The governance of critical infrastructures in German cities. Urban Stud. 2019, 56, 2353–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Shu, T.; Liao, X.; Yang, N.; Ren, Y.; Zhu, M.; Cheng, G.; Wang, J. A new method to evaluate urban resources environment carrying capacity from the load-and-carrier perspective. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 154, 104616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torabi, E.; Dedekorkut-Howes, A.; Howes, M. A framework for using the concept of urban resilience in responding to climate-related disasters. Urban Res. Prac. 2022, 15, 561–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voghera, A. The River agreement in Italy. Resilient planning for the co-evolution of communities and landscapes. Land Use Policy 2020, 91, 104377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voghera, A.; Giudice, B. Evaluating and planning green infrastructure: A strategic perspective for sustainability and resilience. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webber, S.; Leitner, H.; Sheppard, E. Wheeling out urban resilience: Philanthrocapitalism, marketization, and local practice. Ann. Am. Assoc. Geogr. 2020, 111, 343–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetta, G.; Salata, S. Mapping urban resilience for spatial planning—A first attempt to measure the vulnerability of the system. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cariolet, J.M.; Colombert, M.; Vuillet, M.; Diab, Y. Assessing the resilience of urban areas to traffic-related air pollution: Application in Greater Paris. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 615, 588–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelleri, L.; Baravikova, A. Understandings of urban resilience meanings and principles across Europe. Cities 2021, 108, 102985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmutina, K.; Lizarralde, G.; Dainty, A.; Bosher, L. Unpacking resilience policy discourse. Cities 2016, 58, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donovan, B.; Work, D.B. Empirically quantifying city-scale transportation system resilience to extreme events. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2017, 79, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fastiggi, M.; Meerow, S.; Miller, T.R. Governing urban resilience: Organisational structures and coordination strategies in 20 North American city governments. Urban Stud. 2021, 58, 1262–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, B.; Bonczak, B.J.; Gupta, A.; Kontokosta, C.E. Measuring inequality in community resilience to natural disasters using large-scale mobility data. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Medina, P.; Artal-Tur, A.; Sánchez-Casado, N. Tourism business, place identity, sustainable development, and urban resilience: A focus on the sociocultural dimension. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2021, 44, 170–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labaka, L.; Maraña, P.; Giménez, R.; Hernantes, J. Defining the roadmap towards city resilience. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 146, 281–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lak, A.; Hasankhan, F.; Garakani, S.A. Principles in practice: Toward a conceptual framework for resilient urban design. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2020, 63, 2194–2226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lak, A.; Hakimian, P.; Sharifi, A. An evaluative model for assessing pandemic resilience at the neighborhood level: The case of Tehran. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 75, 103410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.S. Towards urban resilience through inter-city networks of co-invention: A case study of US cities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Erickson, T.A.; Meerow, S.; Hobbins, R.; Cook, E.; Iwaniec, D.M.; Berbés-Blázquez, M.; Grimm, N.B.; Barnett, A.; Cordero, J.; Gim, C.; et al. Beyond bouncing back? Comparing and contesting urban resilience frames in US and Latin American contexts. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 214, 104173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poku-Boansi, M.; Cobbinah, P.B. Are we planning for resilient cities in Ghana? An analysis of policy and planners’ perspectives. Cities 2018, 72, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi-Golkhandan, A.; Garvin, M.J.; Wang, Q. Assessing the impact of transportation diversity on postdisaster intraurban mobility. J. Manag. Eng. 2021, 37, 04020106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, S.M.; de Almeida, N.M.; Falcao, M.J.; Duarte, M. Enhancing urban resilience evaluation systems through automated rational and consistent decision-making simulations. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 78, 103612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirgir, E.; Kheyroddin, R.; Behzadfar, M. Defining urban green infrastructure role in analysis of climate resiliency in cities based on landscape ecology theories. TeMA J. Land Use Mobil. Environ. 2019, 12, 227–247. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, F.E.; Millington, J.D.; Jacob, E.; Malamud, B.D.; Pelling, M. Messy maps: Qualitative GIS representations of resilience. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 198, 103771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Q.; Quan, M.; Li, H.; Hao, X. Is environmental regulation works on improving industrial resilience of China? Learning from a provincial perspective. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 4695–4705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Cong, J.; Proverbs, D.; Zhang, L. An evaluation of urban resilience to flooding. Water 2021, 13, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assumma, V.; Bottero, M.; Datola, G.; De Angelis, E.; Monaco, R. Dynamic models for exploring the resilience in territorial scenarios. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beceiro, P.; Brito, R.S.; Galvão, A. Assessment of the contribution of Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) to urban resilience: Application to the case study of Porto. Ecol. Eng. 2022, 175, 106489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitidis, V.; Tapete, D.; Coaffee, J.; Kapetas, L.; Porto de Albuquerque, J. Understanding the implementation challenges of urban resilience policies: Investigating the influence of urban geological risk in Thessaloniki, Greece. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, M.; Gómez-Baggethun, E.; Benayas, J.; Tilbury, D. Towards an urban resilience index: A case study in 50 Spanish cities. Sustainability 2018, 8, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therrien, M.C.; Normandin, J.M.; Paterson, S.; Pelling, M. Mapping and weaving for urban resilience implementation: A tale of two cities. Cities 2021, 108, 102931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K. Global environmental change I: A social turn for resilience? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2014, 38, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmqvist, T. Urban resilience thinking. Solutions 2014, 5, 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- Friend, R.; Moench, M. What is the purpose of urban climate resilience? Implications for addressing poverty and vulnerability. Urban Clim. 2013, 6, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P. Urban resilience for whom, what, when, where, and why? Urban Geo. 2019, 40, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendall, R.; Foster, K.A.; Cowell, M. Resilience and regions: Building understanding of the metaphor. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2010, 3, 71–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, F.S.; Jax, K. Focusing the meaning (s) of resilience: Resilience as a descriptive concept and a boundary object. Ecol. Soc. 2007, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coaffee, J. Risk, resilience, and environmentally sustainable cities. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 4633–4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Star, S.L.; Griesemer, J.R. Institutional ecology, ‘translations’ and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907–1939. Soc. Stud. Sci. 1989, 19, 387–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutman, R. Urban studies as a field of research. Am. Behav. Sci. 1963, 6, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattingly, M. Meaning of urban management. Cities 1994, 11, 201–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popenoe, D. On the meaning of “urban” in urban studies. Urban Aff. Q. 1965, 1, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stren, R. ‘Urban management’ in development assistance: An elusive concept. Cities 1993, 10, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, A.; Griffin, L.; Johnson, C. (Eds.) Environmental Justice and Urban Resilience in the Global South; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgibbons, J.; Mitchell, C.L. Just urban futures? Exploring equity in “100 Resilient Cities”. World Dev. 2019, 122, 648–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerow, S.; Pajouhesh, P.; Miller, T.R. Social equity in urban resilience planning. Local Environ. 2019, 24, 793–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziervogel, G.; Pelling, M.; Cartwright, A.; Chu, E.; Deshpande, T.; Harris, L.; Hyams, K.; Kaunda, J.; Klaus, B.; Michael, K.; et al. Inserting rights and justice into urban resilience: A focus on everyday risk. Environ. Urban. 2017, 29, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, J. A Crude Look at the Whole: The Science of Complex Systems in Business, Life, and Society. Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shamsuddin, S. Urban in Question: Recovering the Concept of Urban in Urban Resilience. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15907. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152215907

Shamsuddin S. Urban in Question: Recovering the Concept of Urban in Urban Resilience. Sustainability. 2023; 15(22):15907. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152215907

Chicago/Turabian StyleShamsuddin, Shomon. 2023. "Urban in Question: Recovering the Concept of Urban in Urban Resilience" Sustainability 15, no. 22: 15907. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152215907

APA StyleShamsuddin, S. (2023). Urban in Question: Recovering the Concept of Urban in Urban Resilience. Sustainability, 15(22), 15907. https://doi.org/10.3390/su152215907