Key Drivers of the Engagement of Farmers in Social Innovation for Marginalised Rural Areas

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background and Literature Review

- A trigger: an external occurrence determining the start of the process [15].

- Individual and collective needs: unmet needs derived from the change in societal structure or economic system, for which a response has not yet been provided by the market or public services. According to Mulgan et al. (2007), SI is characterised by the development and implementation of new ideas for satisfying social needs and creating new social relationships or collaborations [18].

- Perceived context: all tangible and intangible aspects that may favour or obstruct the creation and implementation of SI, such as human capital, social capital, resource endowment, and regulatory framework.

- Agency: the capacity of a group of people to reinterpret and mobilise local resources in response to unmet social needs [34].

- Reconfiguring of social practices: changes in networks among private or public institutions, as well as the development of new attitudes, practices, and governance schemes. Reconfiguration is conceived as a process of social creation, with enhancement of cognitive, rational, and organisational skills [35].

- Activities: actions undertaken after the reconfiguration (i.e., the operational phase of the SI process).

- Outputs: the immediate, identifiable, traceable, and tangible results of SI, paving the way for the creation of further opportunities and leading to a broader range of outcomes and impacts.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Case Study

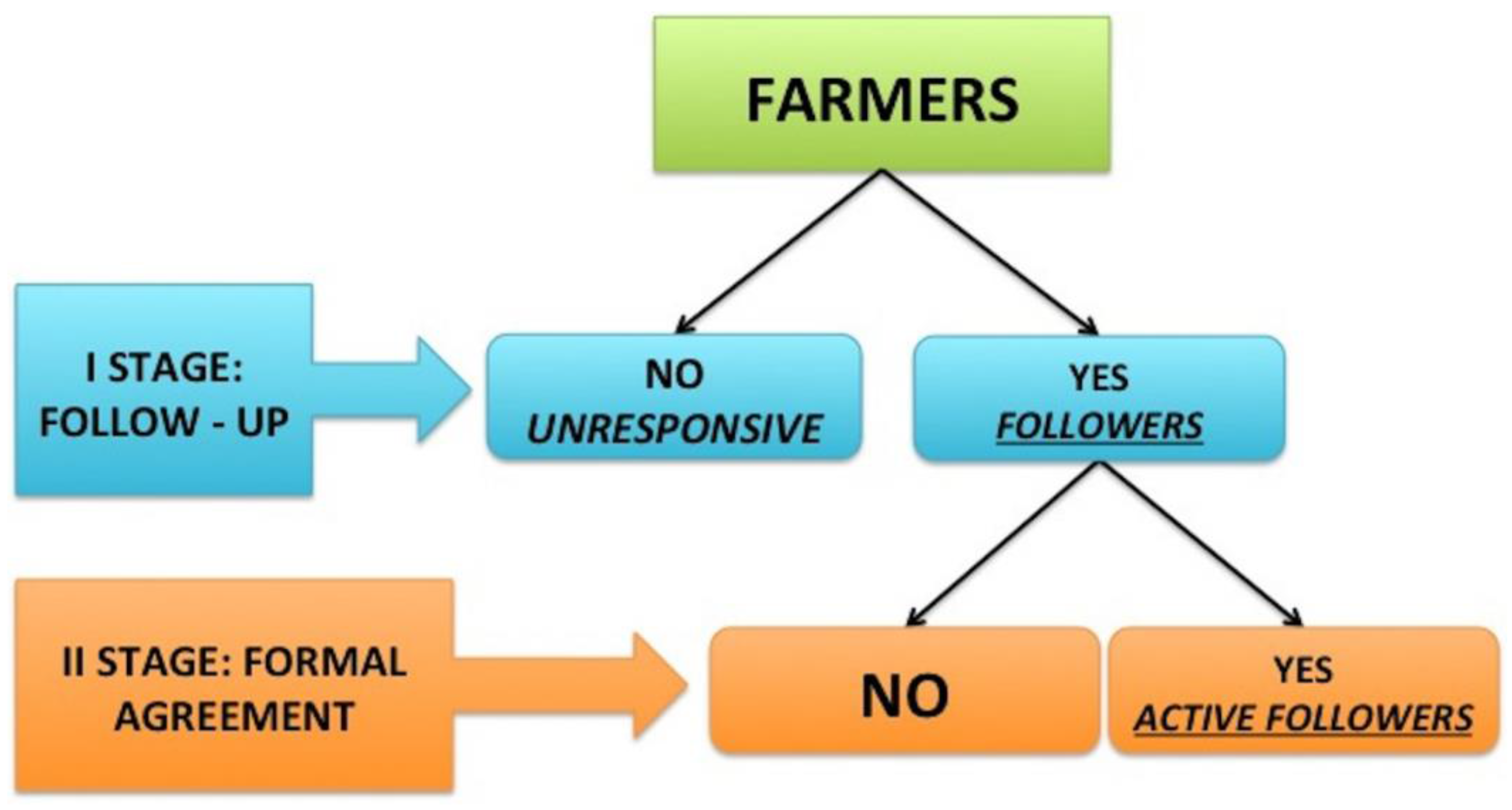

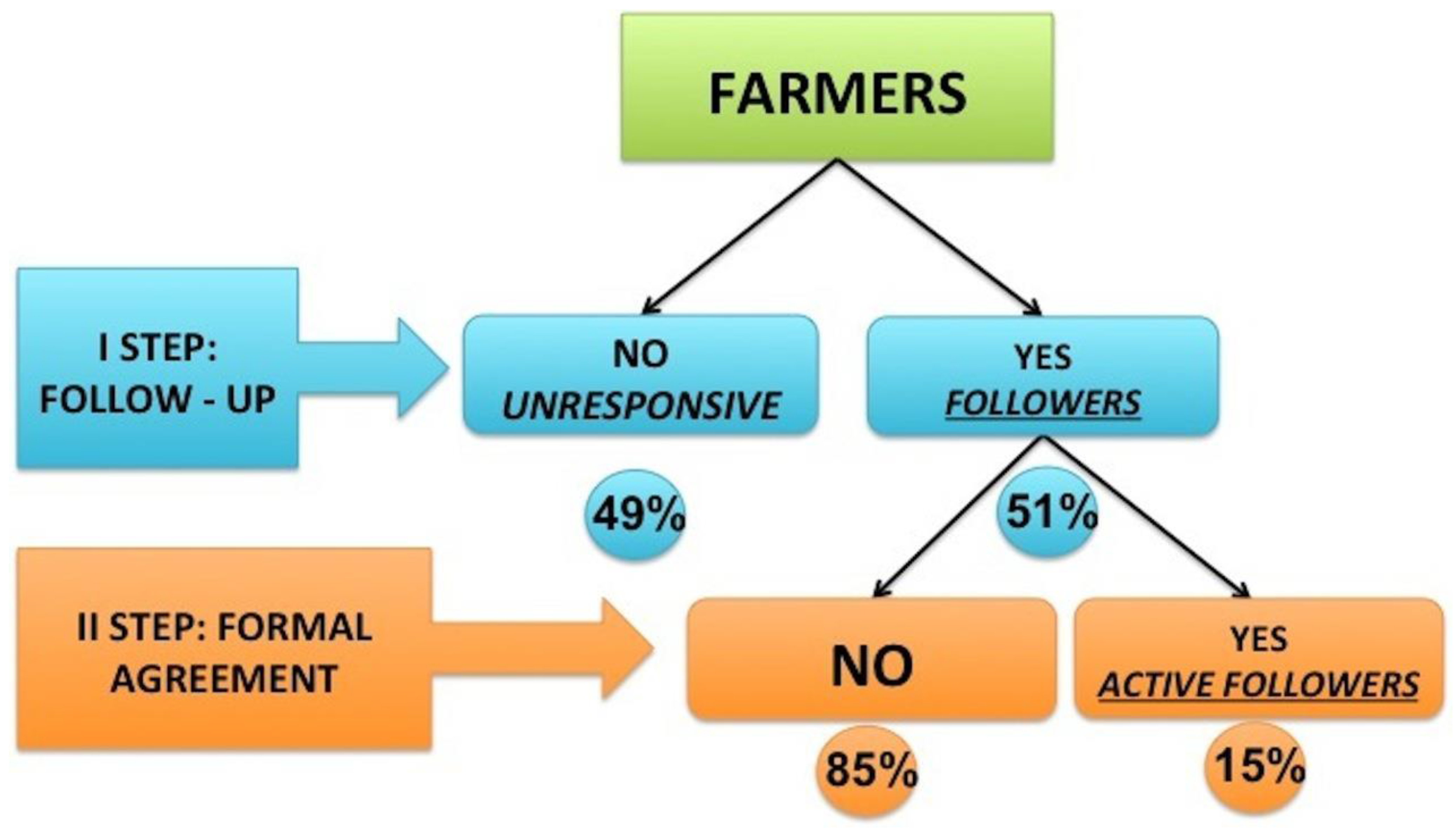

3.2. Data Collection

- Which participants have activated professional agreements with rural hub staff members?

- Which participants have formed a cooperative with other participants?

- Which participants have established project relations with other participants?

3.3. Methodology

- Human capital (H): characteristics of farmers (i.e., age, education);

- Agency (A): effectiveness of agency (i.e., acquaintanceship with the rural hub and agreeableness of the event);

- Marginality (M): physical and social remoteness (i.e., unmet needs among and geographical distance between members).

4. Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

β1,9Need_info + β1,10Need_coop + β1,11Need_chan + β1,12Need_skill + β1,13Need_prom + ε1

β2,9Need_info + β2,10Need_coop + β2,11Need_chan + β2,12Need_skill + β2,13Need_prom + ε2

4.2. Two-Step Model Estimates

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- EARFD—European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development. Resolution on Addressing the Specific Needs of Rural, Mountainous and Remote Areas; Rural Development, EAFRD Resolution 2018/2720(RSP); European Parliament: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, G.A.; Whitehead, I. Local rural product as a ‘relic’ spatial strategy in globalized rural spaces: Evidence from County Clare (Ireland). J. Rural Stud. 2012, 28, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisto, R.; Lopolito, A.; Van Vliet, M. Stakeholder participation in planning rural development strategies: Using backcasting to support Local Action Groups in complying with CLLD requirements. Land Use Policy 2018, 70, 442–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. The Future of the Rural Society. Communication from the Commission to The European Parliament and The Council—COM(88) 501 Final, 28 July 1988. Bulletin of the European Communities, Supplement 4/88; EU Commission: Luxembourg, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ploeg, J.D.; van Dijk, G. (Eds.) Beyond Modernization. The Impact of Endogenous Rural Development; Van Gorcum: Assen, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Lombardi, M.; Lopolito, A.; Andriano, A.M.; Prosperi, M.; Stasi, A.; Iannuzzi, E. Network impact of social innovation initiatives in marginalised rural communities. Soc. Netw. 2020, 63, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Europe 2020 Flagship Initiative Innovation Union. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions; COM (2010) 546 Final; EU Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Lukesch, R.; Ludvig, A.; Slee, B.; Weiss, G.; Živojinović, I. Social innovation, societal change, and the role of policies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slee, B.; Polman, N. An exploration of potential growth pathways of social innovations in rural Europe. Innov. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Res. 2021, 34, 251–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopolito, A.; Nardone, G.; Prosperi, M.; Sisto, R.; Stasi, A. Modeling the bio-refinery industry in rural areas: A participatory approach for policy options comparison. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 72, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscio, A.; Lopolito, A.; Nardone, G. Evaluating social dynamics within technology clusters: A methodological approach to assess social capital. Land Use Policy 2019, 88, 104161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroudi, P.; Akarsu, T.N.; Marvi, R.; Balakrishnan, J. Intellectual evolution of social innovation: A bibliometric analysis and avenues for future research trends. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 93, 446–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Kumar, V.; Karam, E. New-age technologies-driven social innovation: What, how, where, and why? Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 89, 499–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, M. L’innovazione Sociale nel Settore Agricolo del Mezzogiorno; Collana Agricoltura e Benessere, FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 2017; pp. 1–159. [Google Scholar]

- Polman, N.; Slee, W.; Kluvánková, T.; Dijkshoorn, M.; Nijnik, M.; Gežík, V.; Soma, K. Classification of Social Innovations for Marginalized Rural Areas, Deliverable 2.1, Social Innovation in Marginalized Rural Areas (SIMRA). 2017. Available online: http://www.simra-h2020.eu (accessed on 12 May 2021).

- Kluvánková, T.; Brnkaľáková, S.; Špaček, M.; Slee, B.; Nijnik, M.; Valero, D.; Miller, D.; Bryce, R.; Kozová, M.; Polman, N.; et al. Understanding social innovation for the well-being of forest-dependent communities: A preliminary theoretical framework. For. Policy Econ. 2018, 97, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kluvánková, T.; Gežik, V.; Špaček, M.; Brnkaláková, S.; Valero, D.; Bryce, R.; Slee, W.; Alkhaled, D.; Secco, L.; Burlando, C.; et al. Transdisciplinary Understanding of SI in MRAs, Deliverable 2.2, Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas (SIMRA). p. 58. 2017. Available online: http://www.simra-h2020.eu/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/SIMRA_D2_2_Transdisciplinary-_understanding_of_SI_in_MRAs.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2021).

- Ravazzoli, E.; Dalla Torre, C.; Da Re, R.; Marini Govigli, V.; Secco, L.; Górriz-Mifsud, E.; Pisani, E.; Barlagne, C.; Baselice, A.; Bengoumi, M.; et al. Can social innovation make a change in European and Mediterranean marginalized areas? Social innovation impact assessment in agriculture, fisheries, forestry, and rural development. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulgan, G.; Tucker, S.; Ali, R.; Ben Sanders, B. Social Innovation: What It Is, Why It Matters and How It Can Be Accelerated; The Young Foundation: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Drucker, P. Social innovation—Management’s new dimension. Long Range Plan. 1987, 20, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crozier, M.; Friedberg, E. Die Zwänge Kollektiven Handelns über Macht und Organization; Hain: Frankufurt am Main, Germany, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, C.; Baumann, H.; Ruggles, R.; Sadtler, T. Disruptive Innovation for Social Change. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 94–103. [Google Scholar]

- Mulgan, G. The Process of Social Innovation. Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob. 2006, 1, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pol, E.; Ville, S. Social Innovation: Buzz word or ending term? J. Socio-Econ. 2009, 38, 878–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Murray, R.; Caulier-Grice, J.; Mulgan, G. The Open Book of Social Innovation; NESTA: London, UK; Young Foundation: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, A.; Simon, J.; Gabriel, M. Introduction: Dimensions of Social Innovation. In New Frontiers in Social Innovation Research; Nicholls, A., Simon, J., Gabriel, M., Whelan, C., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Secco, L.; Pisani, E.; Burlando, C.; Da Re, R.; Gatto, P.; Pettenella, D.; Vassilopoulus, A.; Akinsete, E.; Koundouri, P.; Lopolito, A.; et al. Deliverable D4.2, Set of Methods to Assess SI Implications at Different Levels: Instructions for WPs 5&6; Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas Project (SIMRA), Demonstrator Submitted to the European Commission; SIMRA: Brussel, Belgium, 2017; Available online: http://www.simra-h2020.eu (accessed on 23 May 2021).

- Secco, L.; Pisani, E.; Da Re, R.; Rogelja, T.; Burlando, C.; Vicentini, K.; Pettenella, D.; Masiero, M.; Miller, D.; Nijnjk, M. Towards a method of evaluating social innovation in forest-dependent rural communities: First suggestions from a science-stakeholder collaboration. For. Policy Econ. 2019, 104, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalla Torre, C.; Ravazzoli, E.; Dijkshoorn-Dekker, M.; Polman, N.; Melnykovych, M.; Pisani, E.; Gori, F.; Da Re, R.; Vicentini, K.; Secco, L. The Role of Agency in the Emergence and Development of Social Innovations in Rural Areas. Analysis of Two Cases of Social Farming in Italy and the Netherlands. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baselice, A.; Prosperi, M.; Marini Govigli, V.; Lopolito, A. Application of a Comprehensive Methodology for the Evaluation of Social Innovations in Rural Communities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marini Govigli, V.; Alkhaled, S.; Arnesen, T.; Barlagne, C.; Bjerck, M.; Burlando, C.; Melnykovych, M.; Rodríguez Fernandez-Blanco, C.; Sfeir, P.; Górriz-Mifsud, E. Testing a Framework to Co-Construct Social Innovation Actions: Insights from Seven Marginalized Rural Areas. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ravazzoli, E.; Dalla Torre, C.; Streifeneder, T.; Pisani, E.; Da Re, R.; Vicentini, K.; Secco, L.; Górriz-Mifsud, E.; Marini Govigli, V.; Melnykovych, M.; et al. Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas Call: H2020-ISIB-2015-2 Innovative, Sustainable and Inclusive Bioeconomy. 2019. Available online: https://scholar.archive.org/work/7kv36aa4vjdrtohn4pnhnju-cy4/access/wayback/https://zenodo.org/record/3666742/files/D5.4_Final%20Report%20on%20Cross-Case%20Study%20Assessment%20of%20Social%20Innovation.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2021).

- Slee, B.; Burlando, C.; Pisani, E.; Secco, L.; Polman, N. Social innovation: A preliminary exploration of a contested concept. Local Environ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewell, W.H., Jr. A theory of structure: Duality, agency, and transformation. Am. J. Sociol. 1992, 98, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howaldt, J.; Kopp, R.; Schwarz, M. Social Innovations as Drivers of Social Change—Exploring Tardes’ Contribution to Social Innovation Theory Building. In New Frontiers in Social Innovation Research; Nicholls, A., Simon, J., Gabriel, A., Eds.; Palgrave: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Secco, L.; Pisani, E.; Da Re, R.; Vicentini, K.; Rogelja, T.; Burlando, C.; Ludvig, A.; Weiss, G.; Zivojinovic, I.; Górriz-Mifsud, E.; et al. Deliverable D4.3, Manual on Innovative Methods to Assess SI and Its Impacts; Social Innovation in Marginalised Rural Areas Project (SIMRA), Report to the European Commission; SIMRA: Brussel, Belgium, 2019; Available online: http://www.simra-h2020.eu (accessed on 23 March 2021).

- Heckman, J.J. Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica 1979, 47, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, B.H.; Rosenberg, N. (Eds.) Handbook of the Economics of Innovation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Blundell, R.; Costa Dias, M. Evaluation methods for non-experimental data. Fisc. Stud. 2000, 21, 427–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, K.; Kinderman, P.; Pontin, E.; Tai, S.; Schwannauer, M. Web based health surveys: Using a Two Step Heckman model to examine their potential for population health analysis. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 163, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, H.C.; Wang, Z.; Boyd, C.; Simoni-Wastila, L.; Buu, A. Associations between statewide prescription drug monitoring program (PDMP) requirement and physician patterns of prescribing opioid analgesics for patients with non-cancer chronic pain. Addict. Behav. 2018, 76, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.H.; Wu, M.W.; Chen, T.H.; Fang, H. To engage or not to engage in corporate social responsibility: Empirical evidence from global banking sector. Econ. Model. 2016, 55, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.Y.; Lin, H.C.; Seo, D.C.; Lohrmann, D.K. Determinants associated with E-cigarette adoption and use intention among college students. Addict. Behav. 2017, 65, 102–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaringelli, M.A.; Giannoccaro, G.; Prosperi, M.; Lopolito, A. Are farmers willing to pay for bioplastic products? The case of mulching films from urban waste. New Medit. 2017, 16, 56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Giannoccaro, G.; de Gennaro, B.C.; De Meo, E.; Prosperi, M. Assessing farmers’ willingness to supply biomass as energy feedstock: Cereal straw in Apulia (Italy). Energy Econ. 2017, 61, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awotide, B.A.; Karimov, A.A.; Diagne, A. Agricultural technology adoption, commercialization and smallholder rice farmers’ welfare in rural Nigeria. Agric. Food Econ. 2016, 4, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, M.H.; Nguyen, T.T.; Grote, U. Shocks and Rural Development Policies: Any Implications for Migrants to Return?, TVSEP Working Paper; No. WP-018; Leibniz Universität Hannover, Thailand Vietnam Socio Economic Panel (TVSEP): Hannover, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, A.; Britz, W. European farms’ participation in agri-environmental measures. Land Use Policy 2016, 50, 214–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Neumeier, S. Spocial Innovation in rural development: Identifying the key factors of success. Geogr. J. 2017, 183, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manski, C.F.; Lerman, S.R. The estimation of choice probabilities from choice-based samples. Econom. J. Econom. Soc. 1977, 45, 1977–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISTAT. 6° Censimento Generale dell’Agricoltura, Atlante dell’Agricoltura Italiana. 2013. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files/2014/03/Atlante-dellagricoltura-italiana.-6%C2%B0-Censimento-generale-dellagricoltura.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2020).

- Centola, D. The spread of behavior in an online social network experiment. Science 2010, 329, 1194–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centola, D.; Macy, M. Complex contagions and the weakness of long tieslex contagions and the weakness of long tie. Am. J. Sociol. 2007, 113, 702–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sigei, G.; Bett, H.; Kibet, L. Determinants of Market Participation among Small-Scale Pineapple Farmers in Kericho County, Kenya; MPRA Paper 56149; University Library of Munich: München, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sall, S.; Norman, D.; Featherstone, A.M. Quantitative Assessment of Improved Rice Variety Adoption: The Farmer’s Perspective. Agric. Syst. 2000, 66, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathijs, E. Social capital and farmers’ willingness to adopt countryside stewardship schemes. Outlook Agric. 2003, 32, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martey, E.; Etwire, P.M.; Wiredu, A.N.; Dogbe, W. Factors influencing willingness to participate in multi-stakeholder platform by smallholder farmers in Northern Ghana: Implication for research and development. Agric. Food Econ. 2014, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Desrochers, P. Geographical proximity and the transmission of tacit knowledge. Rev. Austrian Econ. 2001, 14, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boschma, R.A.; Ter Wal, A.L. Knowledge networks and innovative performance in an industrial district: The case of a footwear district in the South of Italy. Ind. Innov. 2007, 14, 177–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Molina-Morales, F.X.; García-Villaverde, P.M.; Parra-Requena, G. Geographical and cognitive proximity effects on innovation performance in SMEs: A way through knowledge acquisition. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2014, 10, 231–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becattini, G. The Marshallian industrial district as a socioeconomic notion. In Industrial Districts and Inter-Firm Co-Operation; Pyke, F., Beccatini, G., Sengenberger, W., Eds.; International Institute for Labour Studies: Geneva, Switzerland, 1990; pp. 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Castro-Arcè, K.; Vanclay, F. Transformative social innovation for sustainable rural development: An analytical framework to assist community-based initiatives. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 74, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swyngedouw, E.; Moulaert, F. Socially innovative projects, governance dynamics and urban change. In Can Neighborhoods Save the City? Community Development and Social Innovation; Moulaert, F., Martinelli, F., Swyngedouw, E., Gonzales, S., Eds.; Routledge—Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2010; Chapter 15; pp. 219–234. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Variable Description | Coding | Mean | S.D. | Freq. (%) | Missing Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Years | Years | 39.8 | 10.9 | 13 | |

| Gen | Gender | Female | 17.4 | |||

| Male | 82.6 | |||||

| Edu | Education levels | 1 = Primary school 2 = High school 3 = Bachelor’s 4 = Master’s degree 5 = PhD | 10.9 43.0 15.2 22.9 8.0 | 71 | ||

| Pas | Farmers are passionate for agriculture | 0 = no 1 = yes | 46.4 53.6 | |||

| Trad | Tradition and inheritance of family farm | 0 = no 1 = yes | 69.4 30.6 | |||

| Ag_agree | Agreeableness of farmers’ dinner | 5 point Likert scale | 4.7 | 0.5 | 7 | |

| Ag_acqu | Acquaintanceship with VàZapp’ | 0 = no 1 = yes | 20.9 79.1 | 18 | ||

| Km | Farm distance from Foggia city | kilometers | 43.5 | 29.5 | 11 | |

| Need_info | Technical information and solutions | 5 point Likert scale | 3.8 | 1.1 | 46 | |

| Need_coop | Development of cooperative projects for innovation | 5 point Likert scale | 4.0 | 0.9 | 46 | |

| Need_chan | Search for new sales channels | 5 point Likert scale | 4.1 | 1.0 | 42 | |

| Need_skill | Improvement of technical and design skills | 5 point Likert scale | 3.8 | 1.1 | 45 | |

| Need_prom | Promotion of quality products | 5 point Likert scale | 4.2 | 1.0 | 49 |

| STEP 1 | Log likelihood = −160.71386 Marginal effects after probit Y = Pr (WTF) (predict) = 0.66401268 | Number of obs = 251 LR chi2(11) = 22.69 Prob > chi2 = 0.0455 Pseudo R2 = 0.0659 | |||

| Follower | Coef. | Std. Err. | Marg. Eff. | Stat. Sign. | |

| Age | −0.0008217 | 0.0084171 | −0.0003231 | ||

| Edu | 0.0148648 | 0.076784 | 0.005845 | ||

| Gen | 0.1902639 | 0.076784 | 0.0748139 | ||

| Pas | −0.5052452 | 0.1735387 | −0.1947947 | *** | |

| Trad | −0.3370673 | 0.183164 | −0.1330702 | ** | |

| Ag_agre | 0.237426 | 0.1573049 | 0.0933586 | * | |

| Ag_acqu | 0.2692213 | 0.209332 | 0.1058608 | ||

| Km | 0.0004574 | 0.0028874 | 0.0001798 | ||

| Need_info | 0.0652083 | 0.0944524 | 0.0256406 | ||

| Need_coop | −0.0665652 | 0.1024095 | −0.0261742 | ||

| Need_chan | −0.1092995 | 0.1056337 | −0.0429778 | ||

| Need_skill | 0.1888048 | 0.107925 | 0.0742402 | * | |

| Need_prom | −0.0293777 | 0.1061193 | −0.0115516 | ||

| _cons | −1.423013 | 0.91718 | - | * | |

| STEP 2 | Log likelihood = −22.423192 Marginal effects after probit Y = Pr (WTF) (predict) = 0.97938268 | Number of obs = 120 LR chi2(11) = 33.17 Prob > chi2 = 0.0016 Pseudo R2 = 0.4252 | |||

| Active Foll. | Coef. | Std. Err. | Marg. Eff. | Stat. Sign. | |

| Age | 0.0719235 | 0.0359555 | 0.0035733 | * | |

| Edu | −0.3547485 | 0.2183728 | −0.0176246 | ||

| Gen | 0.1311777 | 0.6265455 | 0.0065172 | ||

| Pas | 1.018115 | 0.5294117 | 0.0582865 | * | |

| Trad | 0.1920422 | 0.4914715 | 0.0088896 | ||

| Ag_agree | 1.213596 | 0.4295115 | 0.0602939 | * | |

| Ag_acqu | 1.109044 | 1.109044 | 0.0550996 | * | |

| Km | −0.0217596 | 0.0085803 | −0.0010811 | * | |

| Need_info | −0.278478 | 0.3038714 | −0.0138354 | ||

| Need_coop | −0.0870878 | 0.3258917 | −0.0043267 | ||

| Need_chan | 0.1584284 | 0.2739409 | 0.0078711 | ||

| Need_skill | 0.0303092 | 0.3388764 | 0.0015058 | ||

| Need_prom | −0.3780945 | 0.4188626 | −0.0187845 | ||

| _cons | −5.083182 | 2.83195 | - | * | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Baselice, A.; Lombardi, M.; Prosperi, M.; Stasi, A.; Lopolito, A. Key Drivers of the Engagement of Farmers in Social Innovation for Marginalised Rural Areas. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8454. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158454

Baselice A, Lombardi M, Prosperi M, Stasi A, Lopolito A. Key Drivers of the Engagement of Farmers in Social Innovation for Marginalised Rural Areas. Sustainability. 2021; 13(15):8454. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158454

Chicago/Turabian StyleBaselice, Antonio, Mariarosaria Lombardi, Maurizio Prosperi, Antonio Stasi, and Antonio Lopolito. 2021. "Key Drivers of the Engagement of Farmers in Social Innovation for Marginalised Rural Areas" Sustainability 13, no. 15: 8454. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158454