Perspectives on Comprehensive Sustainability-Orientation in Municipalities: Structuring Existing Approaches

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Which fields of sustainability-oriented local administrations are represented in the literature on sustainable municipalities?

- How can the identified fields of sustainability-oriented local administrations be structured?

- Which differences and similarities exist with regard to the identified fields of sustainability-orientation between the documents representing scientific and practical perspectives?

- What implications can be inferred from the results for research and practical developments on sustainability-oriented local administrations?

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Relevance of Exclusive Fields of Sustainability-Orientation

4.2. Making a Difference Between the Fields of Sustainability-Orientation

4.3. Practice as Example for Science

4.4. Implications for Science and Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| Categories | Amount of Assigned Phrases/Average Frequency | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scientific Articles (N = 9) | ||||||||||||||

| Steurer 2007 | Enticott & Walker 2008 | Garcia-Sanchez & Prado-Lorenzo 2008 | Caragliu et al., 2009 | Fiorino 2010 | Horváth 2011 | |||||||||

| Deductive (Plawitzki et al., 2015) | 1 | Development and consolidation of local sustainability understanding | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 33.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | Development of a local sustainability strategy | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 28.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3 | Supporting sectorial crossing orientation | 2 | 22.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5.9 | 1 | 16.7 | |

| 4 | Defining responsibilities for the coordination of local sustainability activities | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 16.7 | |

| 5 | Support through leadership | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 14.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6 | Establishing transparency of conflicting aims | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 7 | Application of suitable sustainability instruments | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 33.3 | 3 | 17.7 | 1 | 16.7 | |

| 8 | Implementing integrated sustainability communication | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 9 | Signing international commitments and application of norms | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 10 | Implementing participation and cooperation | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 28.6 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 17.7 | 0 | 0 | |

| 11 | Active involvement of state-owned enterprises | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 12 | Relation between local politics and administration | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 17.7 | 0 | 0 | |

| 13 | Care of intercommunal exchange and cooperation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5.9 | 1 | 16.7 | |

| 14 | Strengthening individual motivation and sustainability-oriented culture | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Inductive | 15 | Educating competencies, knowledge and skills | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 33.3 | 3 | 17.7 | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | Supporting innovations | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 17 | Considering long-term perspectives and interdependencies in decision-making | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 11.8 | 0 | 0 | |

| 18 | Implementation of the management cycle | 1 | 11.1 | 1 | 50 | 1 | 14.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 16.7 | |

| 19 | Dealing with public finances | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 20 | Further development of processes, structures and resources | 1 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 14.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 21 | Improving quality and efficiency | 0 | 0 | 1 | 50 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5.9 | 0 | 0 | |

| 22 | Constitution of relations to higher administrative levels | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 16.7 | |

| 9 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 17 | 6 | |||||||||

| Categories | Amount of Assigned Phrases/Average Frequency | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| European City Commitments (N = 4) | |||||||||||||||||

| Glemarec & Oliviera 2012 | Merritt & Stubbs 2012 | Hawkins et al., 2015 | ESC 1994 | ESC 1996 | ESC 2004 | ESC 2010 | |||||||||||

| Deductive (Plawitzki et al., 2015) | 1 | Development and consolidation of local sustainability understanding | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9.1 | 2 | 20 | |

| 2 | Development of a local sustainability strategy | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5.6 | 1 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 3 | Supporting sectorial crossing orientation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 2 | 11.1 | 1 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | Defining responsibilities for the coordination of local sustainability activities | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 5 | Support through leadership | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 6 | Establishing transparency of conflicting aims | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 7 | Application of suitable sustainability instruments | 1 | 20 | 2 | 33.3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 2 | 11.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 8 | Implementing integrated sustainability communication | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 9 | Signing international commitments and application of norms | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 11.1 | 1 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 10 | Implementing participation and cooperation | 1 | 20 | 1 | 16.7 | 1 | 10 | 3 | 30 | 3 | 16.7 | 2 | 18.2 | 2 | 20 | ||

| 11 | Active involvement of state-owned enterprises | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 | ||

| 12 | Relation between local politics and administration | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5.6 | 1 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 13 | Care of intercommunal exchange and cooperation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 30 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 5.6 | 1 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 14 | Strengthening individual motivation and sustainability-oriented culture | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Inductive | 15 | Educating competencies, knowledge and skills | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 2 | 11.1 | 1 | 9.1 | 2 | 20 | |

| 16 | Supporting innovations | 0 | 0 | 1 | 16.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 20 | ||

| 17 | Considering long-term perspectives and interdependencies in decision-making | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 18 | Implementation of the management cycle | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9.1 | 1 | 10 | ||

| 19 | Dealing with public finances | 0 | 0 | 2 | 33.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 20 | Further development of processes, structures and resources | 1 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 21 | Improving quality and efficiency | 2 | 40 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 22 | Constitution of relations to higher administrative levels | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 5 | 6 | 10 | 10 | 18 | 11 | 10 | |||||||||||

| Categories | Amount of Assigned Phrases/Average Frequency | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| German National Reports (N = 2) | Research and Development Projects (N = 4) | |||||||||||||

| Grabow et al., 2011 | Bundes-Regierung 2012 | Klatt et al., 2004 | Philipp et al., 2007 | Büttner & Kneipp 2010 | Nolting & Göll 2012 | |||||||||

| Deductive (Plawitzki et al., 2015) | 1 | Development and consolidation of local sustainability understanding | 4 | 5.6 | 1 | 8.3 | 1 | 4.8 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 14.3 | 2 | 11.1 |

| 2 | Development of a local sustainability strategy | 7 | 9.9 | 2 | 16.7 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 14.3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5.6 | |

| 3 | Supporting sectorial crossing orientation | 3 | 4.2 | 2 | 16.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5.7 | 1 | 5.6 | |

| 4 | Defining responsibilities for the coordination of local sustainability activities | 1 | 1.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 5.7 | 0 | 0 | |

| 5 | Support through leadership | 4 | 5.6 | 1 | 8.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6 | Establishing transparency of conflicting aims | 2 | 2.8 | 1 | 8.3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 7 | Application of suitable sustainability instruments | 9 | 12.7 | 1 | 8.3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.8 | 1 | 2.9 | 1 | 5.6 | |

| 8 | Implementing integrated sustainability communication | 3 | 4.2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.8 | 2 | 9.5 | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | |

| 9 | Signing international commitments and application of norms | 3 | 4.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 10 | Implementing participation and cooperation | 7 | 9.9 | 2 | 16.7 | 8 | 38.1 | 3 | 14.3 | 8 | 22.9 | 6 | 33.3 | |

| 11 | Active involvement of state-owned enterprises | 2 | 2.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 12 | Relation between local politics and administration | 1 | 1.4 | 1 | 8.3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 14.3 | 5 | 14.3 | 0 | 0 | |

| 13 | Care of intercommunal exchange and cooperation | 6 | 8.6 | 1 | 8.3 | 3 | 14.3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.9 | 3 | 16.7 | |

| 14 | Strengthening individual motivation and sustainability-oriented culture | 1 | 1.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.8 | 3 | 8.6 | 1 | 5.6 | |

| Inductive | 15 | Educating competencies, knowledge and skills | 4 | 5.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 16 | Supporting innovations | 1 | 1.4 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 9.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5.6 | |

| 17 | Considering long-term perspectives and interdependencies in decision-making | 2 | 2.8 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 14.3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | |

| 18 | Implementation of the management cycle | 3 | 4.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 28.6 | 3 | 8.6 | 1 | 5.6 | |

| 19 | Dealing with public finances | 4 | 5.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | |

| 20 | Further development of processes, structures and resources | 3 | 4.2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 9.5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2.9 | 0 | 0 | |

| 21 | Improving quality and efficiency | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 22 | Constitution of relations to higher administrative levels | 1 | 1.4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5.6 | |

| 71 | 12 | 21 | 21 | 35 | 18 | |||||||||

References

- UN. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UN. Agenda 21. United Nations Conference on Environment & Development; United Nations: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- UCLG. National and Sub-National Governments on the Way towards the Localization of the SDGs; United Cities and Local Governments: Barcelona, Spain, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rotmans, J.; Loorbach, D. Complexity and Transition Management. J. Ind. Ecol. 2009, 13, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loorbach, D. Transition Management for Sustainable Development: A Prescriptive, Complexity-Based Governance Framework. Governance 2010, 23, 161–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markard, J.; Raven, R.; Truffer, B. Sustainability transitions: An emerging field of research and its prospects. Res. Policy 2012, 41, 955–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, R.; Schot, J.; Hoogma, R. Regime Shifts to Sustainability Through Processes of Niche Formation: The Approach of Strategic Niche Management. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 1998, 10, 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caniglia, G.; Schäpke, N.; Lang, D.J.; Abson, D.J.; Luederitz, C.; Wiek, A.; Laubichler, M.D.; Gralla, F.; von Wehrden, H. Experiments and evidence in sustainability science: A typology. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 169, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäpke, N.; Franziska, S.; Bergmann, M.; Singer-Brodowski, M.; Wanner, M.; Caniglia, G.; Lang, D.J. Reallabore im Kontext transformativer Forschung. Ansatzpunkte zur Konzeption und Einbettung in den internationalen Forschungsstand; Leuphana University Lüneburg: Lüneburg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, B.; Joas, M.; Sundback, S.; Theobald, K. Governing Sustainable Cities; Earthscan: Sterling, TX, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, R.; Parto, S.; Gibson, R.B. Governance for sustainable development: Moving from theory to practice. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 8, 12–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homsy, G.C.; Warner, M.E. Cities and Sustainability: Polycentric Action and Multilevel Governance. Urban Aff. Rev. 2015, 51, 46–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, J. Resilience, ecology and adaptation in the experimental city. Trans. Inst. Br. Geogr. 2011, 36, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellberg, M.M.; Wilkinson, C.; Peterson, G.D. Resilience assessment: A useful approach to navigate urban sustainability. Ecol. Soc. 2015, 20, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibašić, H. Sustainability and Resilience Planning for Local Governments. The Quadruple Bottom Line Strategy; Springer International: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Good Practices, Success Stories and Lessons Learned in SDG Implementation—Call for Submissions. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdgs/goodpractices (accessed on 31 January 2019).

- Plawitzki, J.; Kirst, E.; Heinrichs, H.; Tröster, K.; Pflaum, S.A.; Hübner, S. Kommunale Verwaltung nachhaltig gestalten; Leuphana University Lüneburg: Lüneburg, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rubel, B. Organisatorische Gestaltung der Leistungsbeziehungen in Kommunalverwaltungen. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Cologne, Cologne, Germany, January 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Richter, P. Die Organisation öffentlicher Verwaltung. In Handbuch Organisationstypen; Apelt, M., Tacke, V., Eds.; Springer VS: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2012; pp. 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Wuelser, G.; Pohl, C.; Hirsch Hadorn, G. Structuring Complexity for Tailoring Research Contributions to Sustainable Development: A Framework. Sustain. Sci. 2011, 7, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J.G.; Simon, H.A. Organizations, 2nd ed.; Blackwell Publishers: Cambridge/Oxford, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Plawitzki-Schroeder, J.K. Nachhaltigkeitsorientierte Führung in Kommunalverwaltungen: Zentrale Kompetenzen und deren mögliche Förderung. Ph.D. Thesis, Leuphana University Lüneburg, Lüneburg, Germany, 17 January 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gourmelon, A.; Mroß, M.; Seidel, S. Management im öffentlichen Sektor: Organisationen steuern, Strukturen schaffen, Prozesse gestalten; Rehm: Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nerdinger, F.; Blickle, G.; Schaper, N. Arbeits- und Organisationspsychologie; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Schaltegger, S.; Haller, B.; Müller, A.; Klewitz, J.; Harms, D. Nachhaltigkeitsmanagement in der öffentlichen Verwaltung. Herausforderungen, Handlungsfelder und Methoden; Centre for Sustainability Management, Leuphana Universität Lüneburg: Lüneburg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P.M. The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization; Doubleday/Currency: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D. Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System; The Sustainabilty Institute: Hartland, VT, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bogumil, J. Veränderungen im Kräftedreieck zwischen Bürgern, Politik und Verwaltung. In Verwaltung in NRW; Grunow, D., Ed.; Landeszentrale für öffentliche Bildung: Düsseldorf, Germany, 2003; pp. 109–139. [Google Scholar]

- Gehrlein, U.; Petersson, E. Instrumente, Hemmnisse und Lösungsansätze für eine nachhaltige Kommunalentwicklung; Technische Universität Darmstadt, Zentrum für Interdisziplinäre Technikforschung: Darmstadt, Germany, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, S.; Heinrichs, H.; Horn, D. Kommunale Nachhaltigkeitssteuerung. Umsetzungsstand bei großen Städten und Landkreisen; Institut für den öffentlichen Sektor e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Philipp, N.A.; Kuhn, S.; Kron, D. Handbuch Projekt21. Einstieg in ein zyklisches Nachhaltigkeitsmanagement; ICLEI—Local Governments for Sustainability: Freiburg, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Leuenberger, D.Z.; Wakin, M. Sustainable Development in Public Administration Planning: An Exploration of Social Justice, Equity, and Citizen Inclusion. Adm. Theory Praxis 2007, 29, 394–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuenberger, D.Z.; Bartle, J.R. Sustainable Development for Public Administration; M. E. Sharpe: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2009; pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Fricker, J.; Kägi, E.; Kunz, M.; Müller, U.; Schwaller, B. Nachhaltigkeitsorientierte Führung von Gemeinden. Einführung und Leitfaden für die Praxis; Rüegger Verlag: Chur/Zürich, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Fricker, J.; Sigg, A.; Lentzsch, W.; Frischknecht, P. Das Management-Modell für nachhaltige Gemeinden. GAIA 2004, 13, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehrlein, U. Integration politischer Steuerungsinstrumente für eine nachhaltige Kommunalentwicklung. GAIA 2004, 13, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, P.J.; Vargas, C.M. Implementing Sustainable Development. From Global Policy to Local Action; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Connelly, S.; Markey, S.; Roseland, M. We Know Enough: Achieving Action Through the Convergence of Sustainable Community Development and the Social Economy. In The Economy of Green Cities; Simpson, R., Zimmermann, M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 3, pp. 191–203. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs, H.; Schuster, F. Still some way to go: Institutionalisation of sustainability in German local governments. Int. J. Justice Sustain. 2017, 22, 536–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundesregierung. Nationale Nachhaltigkeitsstrategie. Fortschrittsbericht 2012; Informationsamt der Bundesregierung: Berlin, Germany, 2012.

- Grabow, B.; Beißwenger, K.-D.; Bock, S.; Melcher, L.; Schneider, S. Städte für ein nachhaltiges Deutschland. Gemeinsam mit Bund und Ländern für eine zukunftsfähige Entwicklung; Difu Deutsches Institut für Urbanistik: Berlin, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Steurer, R. From Government Strategies to Strategic Public Management: An Exploratory Outlook on the Pursuit of Cross-Sectoral Policy. Eur. Environ. 2007, 17, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enticott, G.; Walker, R.M. Organizational Strategy: An Empirical Analysis of Public Organizations. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2008, 17, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Sanchez, I.M.; Prado-Lorenzo, J.-M. Determinant Factors in the Degree of Implementation of Local Agenda 21 in the European Union. Sustain. Dev. 2008, 16, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caragliu, A.; del Bo, C.; Nijkamp, P. Smart cities in Europe. In Proceedings of the 3rd Central European Conference in Regional Science—CERS, Kosice, Slovakia, 7–9 October 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorino, D.J. Sustainability as a Conceptual Focus for Public Administration. Public Adm. Rev. 2010, 70, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horváth, G.Á. Administrative Systems and Reforms across the European Union - towards Sustainability? Period. Polytech. Soc. Manag. Sci. 2011, 19, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glemarec, Y.; Puppim de Oliveira, J.A. The Role of the Visible Hand of Public Institutions in Creating a Sustainable Future. Public Adm. Dev. 2012, 32, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merritt, A.; Stubbs, T. Complementing the local and global: Promoting sustainability action through linked local-level and formal sustainability funding mechanism. Public Adm. Dev. 2012, 32, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, C.V.; Krause, R.M.; Feiock, R.C.; Curley, C. Making Meaningful Commitments: Accounting for Variation in Cities’ Investments of Staff and Fiscal Resources to Sustainability. Urban Stud. 2015, 53, 1902–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Sustainable Cities. Charter of European Cities & Towns Towards Sustainability; European Sustainable Cities: Aalborg, Denmark, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- European Sustainable Cities. The Lisboa Action Plan: From Charter to Action; European Sustainable Cities: Lisbon, Portugal, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- European Sustainable Cities. Aalborg+10—Inspiring Futures; European Sustainable Cities: Aalborg, Denmark, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- European Sustainable Cities. The Dunkerque 2010 Local Sustainability Declaration; European Sustainable Cities: Dunkerque, France, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Klatt, S.; Meyer, B.; Petri, T.; Bock, S.; Göschel, A.; Libbe, J.; Reimann, B. Auf dem Weg zur Stadt 2030—Leitbilder, Szenarien und Konzepte. Ergebnisse des Forschungsverbundes ‘Stadt 2030’; BMBF Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung: Berlin, Germany, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Büttner, H.; Kneipp, D. Gemeinsam Fahrt aufnehmen! Kommunale Politik-und Nachhaltigkeitsprozesse integrieren; IFOK GmbH: Berlin/München, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Nolting, K.; Göll, E. „Rio + 20 vor Ort“ Kommunen auf dem Weg zur Nachhaltigkeit; IZT—Institut für Zukunftsstudien und Technologiebewertung gemeinnützige GmbH: Berlin, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. Qualititative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken; Beltz Pädagogik: Weinheim, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Abson, D.; Fischer, J.; Leventon, J.; Newig, J.; Schomerus, T.; Vilsmaier, U.; von Wehrden, H.; Abernethy, P.; Ives, C.D.; Jäger, N.W.; et al. Leverage Points for Sustainability Transformation. Ambio 2017, 46, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smardon, R.C. A Comparison of Local Agenda 21 Implementation in North American, European and Indian Cities. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2008, 19, 118–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kardos, M. The Reflection of Good Governance in Sustainable Development Strategies. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 58, 1166–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portney, K. Civic Engagement and Sustainable Cities in the United States. Public Adm. Rev. 2005, 65, 579–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assmann, D.; Honold, J.; Grabow, B.; Roose, J. SDG-Indikatoren für Kommunen. Indikatoren zur Abbildung der Sustainable Development Goals der Vereinten Nationen in deutschen Kommunen; Bertelsmann Stiftung, Bundesinstitut für Bau-, Stadt- und Raumforschung, Deutscher Landkreistag, Deutscher Städtetag, Deutscher Städte- und Gemeindebund, Deutsches Institut für Urbanistik, Engagement Global: Gütersloh, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Andersen, U.; Woyke, W. (Eds.) Handwörterbuch des politischen Systems der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, 7th ed.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Dusseldorp, M. Zielkonflikte der Nachhaltigkeit: Zur Methodologie wissenschaftlicher Nachhaltigkeitsbewertungen; Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden: Wiesbaden, Germany, 2017; pp. 81–101. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, D.J.; Rode, H.; von Wehrden, H. Methoden und Methodologie in den Nachhaltigkeitswissenschaften. In Nachhaltigkeitswissenschaften; Heinrichs, H., Michelsen, G., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 115–144. [Google Scholar]

- International Sustainability Commitments for Local Governments. Available online: http://www.nachhaltigkeit-kommunal.eu/fileadmin/files/International_Sustainability_Commitments_for_Local_Governments.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2019).

- Sustainable Cities Platform. Available online: http://www.sustainablecities.eu/cities/european-sustainable-cities-and-towns-campaign/ (accessed on 18 October 2018).

- Stadt Freiburg im Breisgau. 1. Freiburger Nachhaltigkeitsbericht 2014; Stadt Freiburg im Breisgau: Freiburg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Geiger, A. Rathaus im Wandel. In 10 Jahre Nachhaltige Stadtentwicklung in Ludwigsburg; Bundesverband für Wohnen und Stadtentwicklung e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2016; pp. 17–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bickel, M.W. A New Approach to Semantic Sustainability Assessment: Text Mining via Network Analysis Revealing Transition Patterns in German Municipal Climate Action Plans. Energy Sustain. Soc. 2017, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newig, J.; Fritsch, O. Environmental Governance: Participatory, Multi-Level—and Effective? Environ. Policy Gov. 2009, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esty, D.C. Red Lights to Green Lights: From 20th Century Environmental Regulation to 21st Century Sustainability. Environ. Law 2017, 47, 1–80. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, G.; Steurer, R. Horizontal Policy Integration and Sustainable Development: Conceptual Remarks and Governance Examples. In ESDN Quarterly Reports; European Sustainable Development Network: Vienna, Austria, 2009; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Willke, H. Systemisches Wissensmanagement; Lucius & Lucius: Stuttgart, Germany, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez, P.; Probst, G. Die Praxis des ganzheitlichen Problemlösens, 3rd ed.; Haupt Verlag: Bern, Switzerland; Stuttgart, Germany; Wien, Austria, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Vahs, D. Organisation. Einführung in die Organisationstheorie und -Praxis, 6th ed.; Schäffer-Poeschel: Stuttgart, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Wiek, A.; Binder, C. Solution Spaces for Decision-Making—A Sustainability Assessment Tool for City-Regions. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2005, 25, 589–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittelstraß, J. Methodische Transdiziplinarität. Technologiefolgenabschätzung—Theorie und Praxis 2005, 14, 18–23. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, M.; Jahn, T.; Knobloch, T.; Krohn, W.; Schramm, E.; Thompson Klein, J.; Faust, R.C. Methods for Transdisciplinary Research: A Primer for Practice; Campus Verlag GmbH: Frankfurt-on-Main, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, D.J.; Wiek, A.; Bergmann, M.; Stauffacher, M.; Martens, P.; Moll, P.; Swilling, M.; Thomas, C.J. Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: Practice, principles, and challenges. Sustain. Sci. 2012, 7, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterlin, J.; Pearse, N.; Dimovski, V. Strategic decision making for organizational sustainability: The implications of servant leadership and sustainable leadership approaches. Econ. Bus. Rev. 2015, 17, 273–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, R.M.; Feiock, R.C.; Hawkins, C.V. The Administrative Organization of Sustainability Within Local Government. J. Public Adm. Res. Theory 2016, 26, 113–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Perspective | Document Group | Author/Editor | Title | Year | Scope of Regional Reference | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scientific | Scientific articles (SA) N = 13 | a) | R. Steurer | From Government Strategies to Strategic Public Management: An Exploratory Outlook on the Pursuit of Cross-Sectoral Policy Integration | 2007 | Europe | [42] |

| b) | G. Enticott, R.M. Walker | Sustainability, Performance and Organizational Strategy: An Empirical Analysis of Public Organizations | 2008 | England | [43] | ||

| c) | I.M. Garcia-Sanchez, J.-M. Prado-Lorenzo | Determinant Factors in the Degree of Implementation of Local Agenda 21 in the European Union | 2008 | Europe | [44] | ||

| d) | A. Caragliu, del B. Chiara., P. Nijkamp | Smart Cities in Europe | 2009 | Europe | [45] | ||

| e) | D.J. Fiorino | Sustainability as a Conceptual Focus for Public Administration | 2010 | International | [46] | ||

| f) | G.A. Horváth | Administrative Systems and Reforms across the European Union - towards Sustainability? | 2011 | Europe | [47] | ||

| g) | Y. Glemarec, J.A. Puppim de Oliveira | The Role of the Visible Hand of Public Institutions in Creating a Sustainable Future | 2012 | International | [48] | ||

| h) | A. Merrit, T. Stubbs | Complementing the Local and Global: Promoting Sustainability Action through Linked Local-Level and Formal Sustainability Funding Mechanisms | 2012 | South Africa, United Kingdom | [49] | ||

| i) | C.V. Hawkins, R.M. Krause, R.C. Feiock, C. Curley | Making Meaningful Commitments: Accounting for Variation in Cities | 2015 | United States of America | [50] | ||

| Practical | European city commitments (ECC) N = 4 | j) | European Sustainable Cities | Charter of European Cites & Towns Towards Sustainability | 1994 | Europe | [51] |

| k) | European Sustainable Cities | Lissabonner Aktionsplan | 1996 | Europe | [52] | ||

| l) | European Sustainable Cities | Aalborg+ 10—Inspiring Futures | 2004 | Europe | [53] | ||

| m) | European Sustainable Cities | The Dunkerque 2010 Local Sustainability Declaration | 2010 | Europe | [54] | ||

| German national reports (GNR) N = 2 | n) | B. Grabow, K.-D. Beißwenger, S. Bock, L. Melcher, S. Schneider | Städte für ein nachhaltiges Deutschland. Gemeinsam mit Bund und Ländern für eine zukunftsfähige Entwicklung (Cities for a Sustainable Germany. Together with Federal Government and Federal States for a Future-oriented Development) | 2011 | Germany | [41] | |

| o) | Presse- und Informationsamt der Bundesregierung (ed.) | Nationale Nachhaltigkeitsstrategie. Fortschrittsbericht 2012: Kapitel I. Nachhaltigkeit auf kommunaler Ebene—Beitrag der Bundesvereinigung der kommunalen Spitzenverbände (National Sustainability Strategy. Progress Report 2012: Chapter I. Sustainability on the Local Level—a Contribution of the Local Authority Associations) | 2012 | Germany | [40] | ||

| Research and development projects (RDP) N = 4 | p) | S. Klatt, B. Meyer, T. Petri | Auf dem Weg zur Stadt 2030 - Leitbilder, Szenarien und Konzepte (Towards City 2030 - Guiding Principles, Scenaries and Concepts) | 2004 | Germany | [55] | |

| q) | N.A. Philipp, S. Kuhn, D. Kron | Handbuch Projekt21. Einstieg in ein zyklisches Nachhaltigkeitsmanagement (Handbook Project21. Introduction into a Cyclic Sustainability Management) | 2007 | Germany | [31] | ||

| r) | H. Büttner, D. Kneipp | Gemeinsam Fahrt aufnehmen! Kommunale Politik- und Nachhaltigkeitsprozesse integrieren (Commonly Gain Momentum! Integrating Politic and Sustainability Processes in Municipalities) | 2010 | Germany | [56] | ||

| s) | K. Nolting, E. Göll | “Rio + 20 vor Ort” Kommunen auf dem Weg zur Nachhaltigkeit (“Rio + 20 on Site” Municipalities towards sustainabilty) | 2012 | Germany | [57] |

| Categories | Amount of Assigned Phrases/Average Frequency/Standard Deviation of Frequency | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA (N = 9) | ECC (N = 4) | GNR (N = 2) | RDP (N = 4) | Total | |||||||||||||

| Deductive (Plawitzki et al., 2015) | 1 | Development and consolidation of local sustainability understanding | 1 | 3.7 | 10.5 | 5 | 12.3 | 8.4 | 5 | 7.0 | 1.3 | 8 | 7.5 | 5.5 | 19 | 6.7 | 9.2 |

| 2 | Development of a local sustainability strategy | 3 | 4.4 | 9.2 | 2 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 9 | 13.3 | 3.4 | 4 | 5.0 | 5.8 | 18 | 5.3 | 7.7 | |

| 3 | Supporting sectorial crossing orientation | 4 | 5.0 | 8.1 | 4 | 7.6 | 4.4 | 5 | 10.4 | 6.2 | 3 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 16 | 5.6 | 6.8 | |

| 4 | Defining responsibilities for the coordination of local sustainability activities | 3 | 4.1 | 7.7 | 1 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 1 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 2 | 1.4 | 2.5 | 7 | 2.6 | 5.7 | |

| 5 | Support through leadership | 1 | 1.6 | 4.5 | 1 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 5 | 7.0 | 1.3 | 1 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 8 | 1.9 | 3.8 | |

| 6 | Establishing transparency of conflicting aims | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3 | 5.6 | 2.8 | 1 | 1.2 | 2.1 | 4 | 0.8 | 2.1 | |

| 7 | Application of suitable sustainability instruments | 8 | 13.4 | 13.3 | 3 | 5.3 | 5.3 | 10 | 10.5 | 2.2 | 3 | 3.3 | 2.1 | 24 | 9.3 | 10.5 | |

| 8 | Implementing integrated sustainability communication | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 3 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 4 | 4.3 | 3.5 | 8 | 1.4 | 2.6 | |

| 9 | Signing international commitments and application of norms | 1 | 1.1 | 3.1 | 3 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 3 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7 | 1.8 | 3.7 | |

| 10 | Implementing participation and cooperation | 9 | 11.6 | 9.6 | 10 | 21.2 | 5.2 | 9 | 13.3 | 3.4 | 25 | 27.1 | 9.2 | 53 | 17.0 | 10.5 | |

| 11 | Active involvement of state-owned enterprises | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.5 | 4.3 | 2 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3 | 0.7 | 2.3 | |

| 12 | Relation between local politics and administration | 4 | 3.2 | 6.2 | 2 | 3.7 | 3.9 | 2 | 4.9 | 3.4 | 8 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 16 | 4.3 | 6.0 | |

| 13 | Care of intercommunal exchange and cooperation | 5 | 5.8 | 10.0 | 3 | 6.2 | 3.9 | 7 | 8.4 | 0.1 | 7 | 8.5 | 7.1 | 22 | 6.7 | 7.9 | |

| 14 | Strengthening individual motivation and sustainability-oriented culture | 1 | 1.2 | 3.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 5 | 4.7 | 3.1 | 7 | 1.7 | 3.2 | |

| Inductive | 15 | Educating competencies, knowledge and skills | 5 | 6.9 | 11.1 | 6 | 12.6 | 4.4 | 4 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 15 | 6.2 | 9.0 |

| 16 | Supporting innovations | 1 | 1.9 | 5.2 | 2 | 5.0 | 8.7 | 1 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 3 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 7 | 2.8 | 5.9 | |

| 17 | Considering long-term perspectives and interdependencies in decision-making | 2 | 1.3 | 3.7 | 1 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 2 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 4 | 4.3 | 5.9 | 9 | 2.0 | 4.1 | |

| 18 | Implementation of the management cycle | 4 | 10.2 | 15.5 | 3 | 7.3 | 4.2 | 3 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 10 | 10.7 | 10.8 | 20 | 8.8 | 12.2 | |

| 19 | Dealing with public finances | 2 | 3.7 | 10.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4 | 2.8 | 2.8 | 1 | 0.7 | 1.2 | 7 | 2.2 | 7.5 | |

| 20 | Further development of processes, structures and resources | 5 | 7.3 | 8.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 3 | 3.1 | 3.9 | 11 | 4.3 | 6.8 | |

| 21 | Improving quality and efficiency | 4 | 10.7 | 18.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.2 | 2.1 | 5 | 5.3 | 13.8 | |

| 22 | Constitution of relations to higher administrative levels | 2 | 3.0 | 5.8 | 1 | 2.3 | 3.9 | 1 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 2 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 6 | 2.5 | 4.6 | |

| 65 | 49 | 83 | 95 | 292 | |||||||||||||

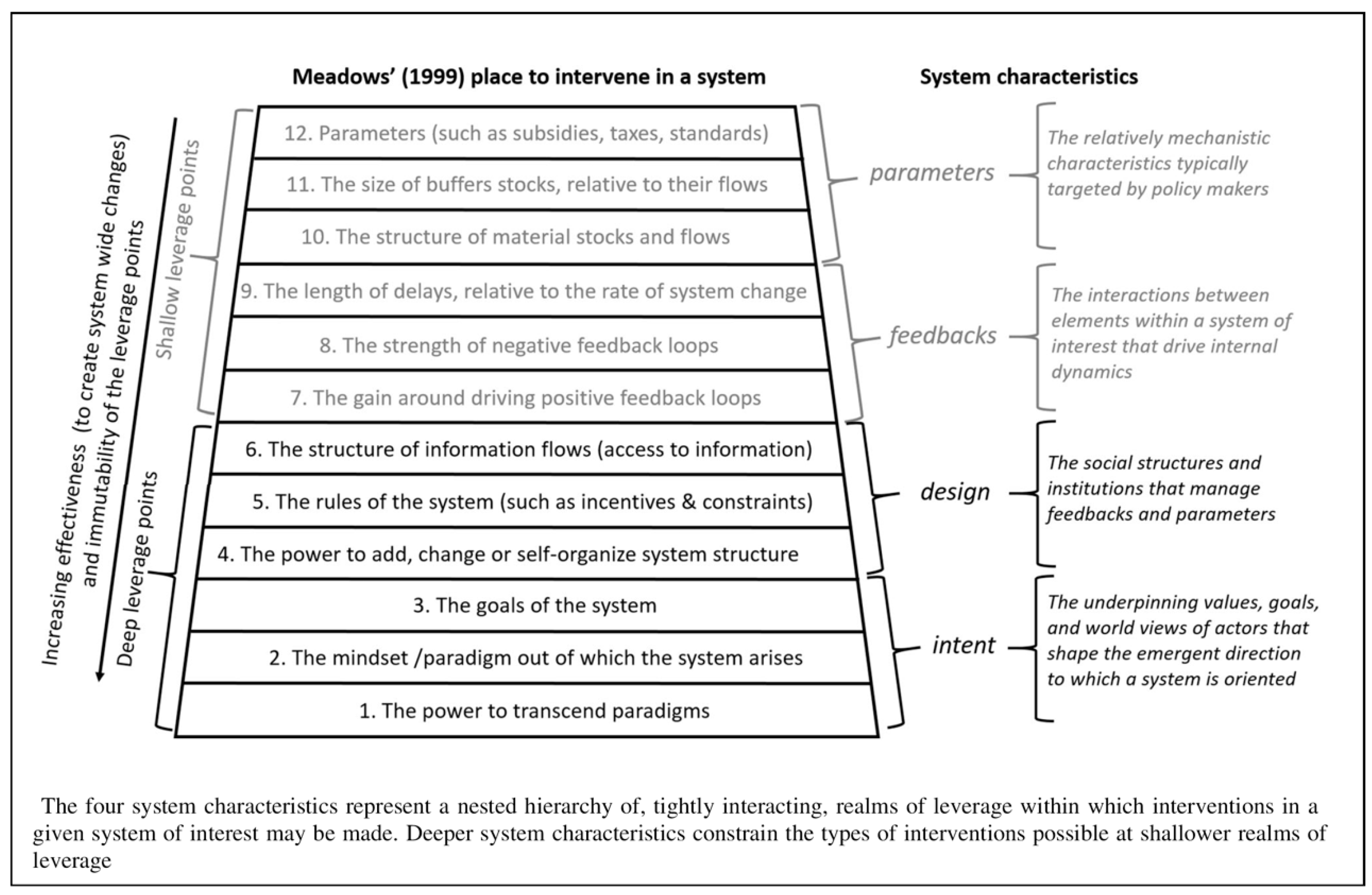

| Fields on Sustainability-Orientation in Local Administrations | Description (1, 4–8, 10–13, 15–19 and Parts of 3 Adapted to Plawitzki et al., 2015) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| System characteristics (Abson et al., 2017) | Parameter | 1 | Signing international commitments and application of norms | Signing border-crossing commitments and compliance with norms to support local sustainable development |

| 2 | Dealing with public finances | Dealing with public finances in order to support a sustainable local development | |||

| Feedback | 3 | Considering long-term perspective, interdependencies and conflicting aims | Considering long-term perspectives and interdependencies as well as transparency of conflicting aims on sustainability topics in order to support political decision-makers with comprehensive information as basis for decision-making | ||

| 4 | Relation between local politics and administration | Ideal interrelation between local authorities and politicians to successfully implement measures of sustainability management and practice | |||

| Design | 5 | Preparation of a local sustainability strategy | Bundling of sustainability actions of the local administration in a sustainability strategy that contains future-oriented guidelines, strategic aims and tangible measures as well as practical instructions | ||

| 6 | Defining responsibilities for the coordination of local sustainability activities | Staff and institutional commitment of responsibilities for the coordination of sustainability activities of the local administration, scope of action depends on the placement in the hierarchical, administrational system | |||

| 7 | Application of suitable sustainability instruments | Efficient and strategic application of instruments of the broad spectrum of sustainability instruments | |||

| 8 | Supporting sectoral crossing orientation | Integration of sustainability aspects in organizational structures and processes of all hierarchical levels and functional departments in the administration | |||

| 9 | Implementation of the management cycle | Implementing a management cycle including analysis, planning, implementation and evaluation | |||

| 10 | Implementing integrated sustainability communication | Implementing a comprehensive sustainability communication that contains a strategic process of dialogue in the local administration and with external stakeholders about manifold topics and using divers channels | |||

| 11 | Supporting innovations | Supporting innovations by creating constraints, respectively and/or implementing initiatives and projects by the local administration itself | |||

| Intent | 12 | Development and consolidation of local sustainability understanding | Specifying the understanding of sustainability and focusing on particular topics as well as their regularly evaluation, elaborating a common level of awareness on the term sustainability and sustainability understanding of the public administrators | ||

| 13 | Support through leadership | Using the potential of leadership for the integration of sustainability-orientation in administrational routines | |||

| 14 | Educating competencies, knowledge and skills | Implementing measures of professional training for public administrators to educating competencies, supporting skills and acquiring knowledge, which are relevant for fostering sustainable development | |||

| 15 | Strengthening individual motivation and sustainability-oriented culture | Positive impacts on the implementation of sustainability management by motivated staff and a sustainability-oriented administrational culture | |||

| Additional area | Interface | 16 | Implementing participation and cooperation | Implementing processes of participation and cooperation to sufficiently inform internal and external actor groups and to engage them in decision-making and operative processes of local sustainable development | |

| 17 | Active involvement of state-owned enterprises | Using the potential of state-owned enterprises for implementing sustainable development by actively involving them | |||

| 18 | Intercommunal exchange and cooperation | Intercommunal networking for the exchange of experiences, knowledge and information and for potentially initiating cooperation | |||

| 19 | Constitution of relations to higher administrative levels | Constitution of relations to higher administrative levels (region, federal state, nation, European level) |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kirst, E.; Lang, D.J. Perspectives on Comprehensive Sustainability-Orientation in Municipalities: Structuring Existing Approaches. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1040. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041040

Kirst E, Lang DJ. Perspectives on Comprehensive Sustainability-Orientation in Municipalities: Structuring Existing Approaches. Sustainability. 2019; 11(4):1040. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041040

Chicago/Turabian StyleKirst, Ev, and Daniel J. Lang. 2019. "Perspectives on Comprehensive Sustainability-Orientation in Municipalities: Structuring Existing Approaches" Sustainability 11, no. 4: 1040. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041040

APA StyleKirst, E., & Lang, D. J. (2019). Perspectives on Comprehensive Sustainability-Orientation in Municipalities: Structuring Existing Approaches. Sustainability, 11(4), 1040. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041040