1. Introduction

In Chile, as in many other countries in Latin America and in the world, private conservation significantly contributes to national protected areas [

1,

2,

3]. According to the IUCN guidelines, Private Protected Areas (PPAs) are defined as those “

under individual, cooperative, NGO or corporate control and/or ownership, and managed under non- profit or for-profit schemes […] [where] the authority for managing the protected land and resources rests with the landowners, who determine the conservation objective, develop and enforce management plans and remain in charge of decisions, subject to applicable legislation” [

4]. In Chile this tendency towards private conservation has been observed since the beginning of the 1990s. These initiatives are carried out by either foreigners or national citizens or non-governmental organizations with different non-profit or for-profit goals, such as biodiversity conservation, bio carbon sequestration, ecosystem services and ecotourism [

5].

Chile specifically has adopted a very neoliberal approach to their national economy. With the beginning of the Pinochet regime in 1973, governmental institutions were diminished, and private property rights were strengthened [

6], promoting foreign investments in the primary sector as well as land sales for conservation. Over the last three decades, this tendency was facilitated by three factors: (i) the retreat of governmental institutions and the increase of NGOs managing protected areas; (ii) the integration of conservation in market mechanisms as a characteristic of global neoliberal capitalism; and (iii) leading conservation NGOs have developed relationships with corporations copying their methods in areas such as marketing and receiving their donations [

7]. Therefore, valuable land is increasingly integrated in market mechanisms. Land with a high conservation value is sold for ecotourism, or as payment for ecosystem services. Since the 1980s and mainly since the 2000s, NGOs have been cooperating with corporations and have allowed their activities to be viewed as positive [

8,

9,

10]. However, in Chile, formal recognition of PPAs is inhibited by a lack of implemented regulations [

11].

In Latin America, Chile plays a special role in private conservation. It is the only state with 2.2% of its territory under private protection, making it one of the nations with the highest proportion of private conservation areas. Only small countries such as Costa Rica and Belize have a bigger relative share of their territory under private conservation [

12]. 19.2% of Chile’s territory is protected in the National Park System known as SNASPE (Sistema Nacional de Áreas Silvestres Protegidas del Estado) [

12]. Furthermore, Chile has 308 Private Protected Areas, with an estimated area of 1,651,916 ha [

13].

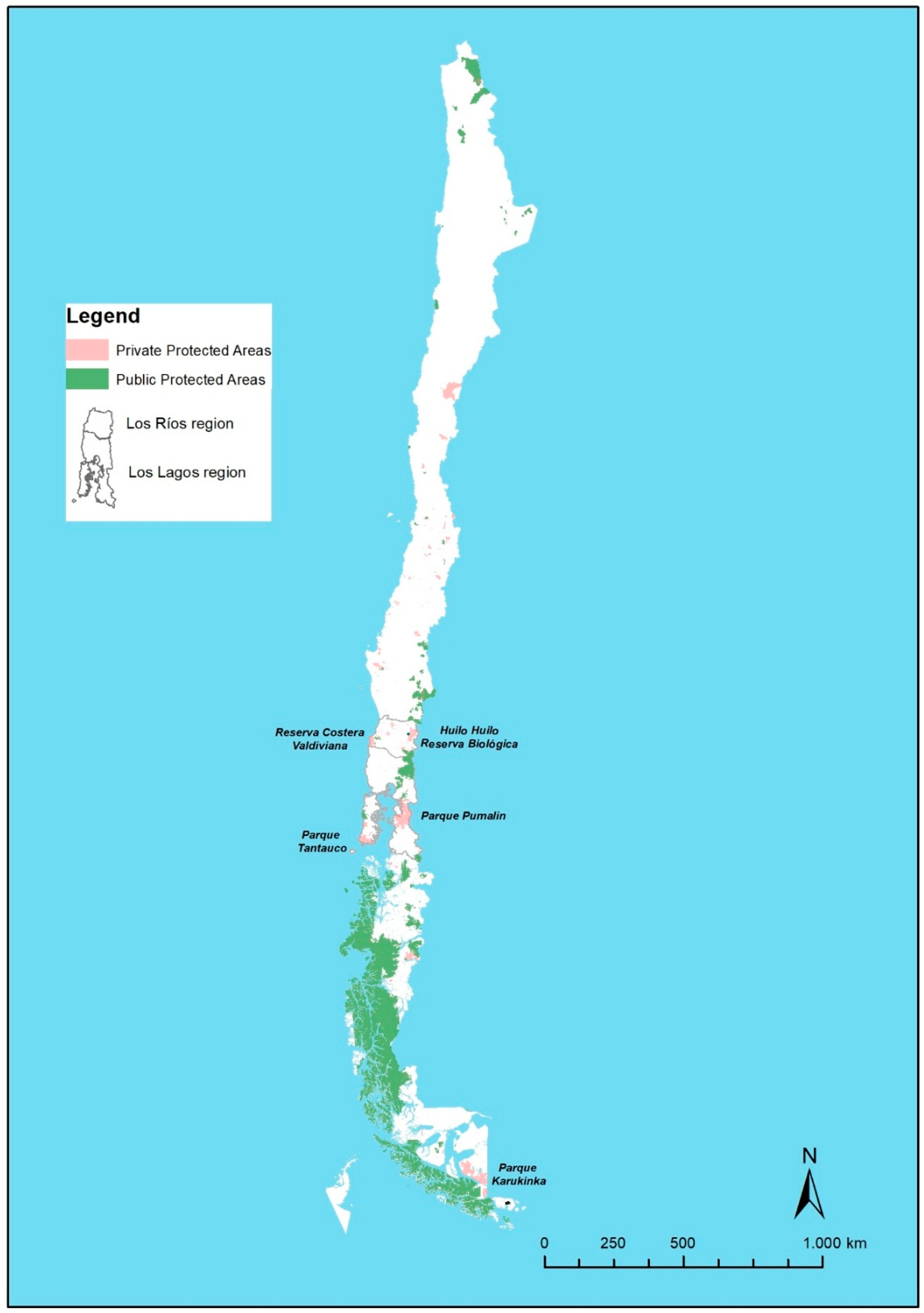

Figure 1 shows the distribution of public and private parks in Chile. In 2013, there were 308 private initiatives in Chile. There is an evident concentration of these undertakings in southern Chile, especially in the Los Ríos (72 areas) and Los Lagos regions (86 areas).

Private conservation areas are relevant in Chile because of two key factors: first, they are considered as complementary, as the Chilean national park system does not cover all threatened biomes of Chilean flora and fauna and are vulnerable to boundary problems with other land uses [

14]. Secondly, private protected areas are considered to be a tool for promoting local development. Over the past five years, the Chilean Ministry of the Environment has proposed changes in legislation in order to transform these types of conservation projects into attractions, in order to use them as an investment for tourism. Projects in rural areas and remote zones encouraged the development of the local economy. Private protected areas were encouraged to apply for funding for environmental conservation, improving public and private alliances [

15]. According to [

16,

17] central and southern Chile, where most of the private protected areas are located, is a conservation hot spot on a global scale. The Valdivian Rain forest eco-region is one of only five temperate rainforests worldwide. The biome is highly threatened because of large-scale logging, small-scale firewood extraction, forest fires, clearing, salmon production and penetration of highways. The habitat of the threatened pudú (world smallest deer) correlates with this biome [

18]. This threat of land use change occurs more or less in all areas of the biome, which is not under the protection of the national park system. However, the forests in the fjord lands of Patagonia are less vulnerable as the population density is very low.

In

Table 1 the 15 largest private protected areas in Chile are shown by their size, regional location, ownership and year of creation. The majority of these areas are located in the southern regions of Chile and their creation took place from the early 1990s until 2013 with the Fundación Yendegaia in Tierra del Fuego. The first to be implemented in Chile was Pumalín Park in 1991 of over 284.630 ha. This park became a pioneer initiative, showing how PPAs could become important territorial figures, leading not only to conservation but also to the transformation of an isolated locality such as Chaitén, into one of the most well-known mountain destinations of southern Chile.

Private Protected Areas as Mechanism for Promoting Local Development

Ref. [

19] stated that there are many reasons why PPAs play key roles, not only filling gaps in national biodiversity conservation strategies, but also because they can bolster resource management, enhance citizen participation, promote bottom-up management as well as be a lucrative investment if they are linked to low-impact activities such as small forestry, organic agriculture or ecotourism. According to [

20,

21] activities such as ecotourism allow economic value to be assigned to natural resources, helping reduce social inequality; [

11,

21] added that these activities lead to economic transformations at the local level. However, [

22] mentioned that there is a lack of literature exploring the social impact of private protected areas, and how they vary according to the different types of ownership of PPAs, especially in ecotourism and their relationship with human well-being. According to [

23] little attention has been drawn to the function of PPAs in the promotion of sustainable development, particularly in the context of the debate around the relationship between people and protected areas. This situation is particularly sensitive in mountain areas, due to the fact that they are often marginalized areas, where poverty alleviation remains a core challenge [

24]. In this paper, the authors suggest that investing in mountain areas is essential and could offer attractive opportunities for investors interested not only in short-term gains, but also especially in long-term returns on their contributions and enhancing local wellbeing. This could be one of the motivations of PPA owners.

Additionally, [

25,

26] hows in international studies that successful conservation and socio-economic prosperity in the surrounding area are interdependent. Effective conservation involves support and collaboration from the local governments and communities. In turn, this requires that protected areas contribute to the economic well-being of the communities in which they are located. For instance, in Brazil private conservation was investigated by [

27] in the context of ecotourism and conservation. In the study, it was shown that small private protection projects (<50 ha) are successful in ecotourism. The assumption then that large reserves are necessary for conservation is challenged.

In the state of New South Wales in Australia, a study was carried out by [

25] in order to investigate the socio-economic effects of conservation in the area. Three mechanisms were described on how protected areas could have a positive effect on the surroundings. These are improved real estate values, local business stimulus and increased local funding pathways. New protected areas led to an increased number of new dwelling approvals and associated developer contributions, an increase in local business, and increased local government revenue from user-payments for services and grants.

In the Chinese Wolong Nature Reserve, [

28] investigated the economic participation of local residents in the tourism industry. Due to the economic marginalism and ethnic heterogeneity of the local people they are excluded from tourism revenues. Non-local residents with a better economic situation profit from tourism. A small number of local people with skills, start-up capital, and an advantageous location receive some limited income from tourism. This is a common phenomenon in developing countries. The authors suggest the following recommendations to improve local participation in tourism activities: local capacities need to be improved through education and training and the diversification of ecologically viable tourism products based on the natural and cultural characteristics of the destination. Financial support and economic compensation mechanisms should be established for underprivileged local stakeholders. Tax leverage may be useful for rational distribution of development revenues and conservation costs.

In southern Chile, some initiatives have been studied. In fact, [

29] described the case of Oncol Park, located in the Chilean Coastal Range, in the Los Ríos region within the Valdivian temperate rainforest, which is a biodiversity hotspot and one of the few remaining endemic forests in the area. This PPA is an example of how private sector companies can develop concrete initiatives that have a positive impact on the local economy by opening up a range of income-generating opportunities, assuming that they are easily accessible and have a good connection to local and regional centers. Ref. [

8] analyzed the social impacts of the Huilo Huilo Biological Reserve, one of the biggest PPAs in Los Rios regions located in Neltume, a small rural village. The study reveals how tourism activities, most of them linked to the Huilo Huilo project, were implemented in response to the decline of the forestry industry, a major activity over the last 30 years. At the same time, [

3] conducted a comparative study in the same region, considering different PPAs, which differ in size and types of ownership such as Huilo Huilo (managed by Victor Petermann, a private entrepreneur), the Valdivian Coastal Reserve (managed by NGO The Nature Conservancy) and the Oncol Park (managed by the forestry company Forestal Valdivia). The study suggests that the social impact and consequences of PPAs facilitating ecotourism development should be subjected to the same level of scrutiny that has been given to public protected areas. PPA ecotourism ventures could improve the well-being of local inhabitants as well as degrade it. If private protected areas reach a viable level, they could become an incentive for local people with start-up capital and the willingness to engage in entrepreneurial endeavors.

Different parks have been investigated focusing on surrounding communities’ perceptions in order to bring the study into a theoretical context. Among these were the Iron Gate Natural Park in south-western Romania. Management recommendations for park administration are given and the participation of local communities is recommended [

30]. In the Prespes Lakes National Park in north-western Greece the local population’s perception of the park was investigated. The need for a new administration and management scheme with the participation of local communities in the decision-making process was revealed. Results of this research show that the information derived from a participatory process could help managers of protected areas resolve potential conflicts [

31]. When neighbors of the Ecuadorian National Park Machalilla were consulted about how they saw the park, the majority held a variety of negative opinions. These opinions improved in residents with higher education, knowledge about conservation issues and who belonged to a younger age group [

32].

The Pumalín Project in Chaitén

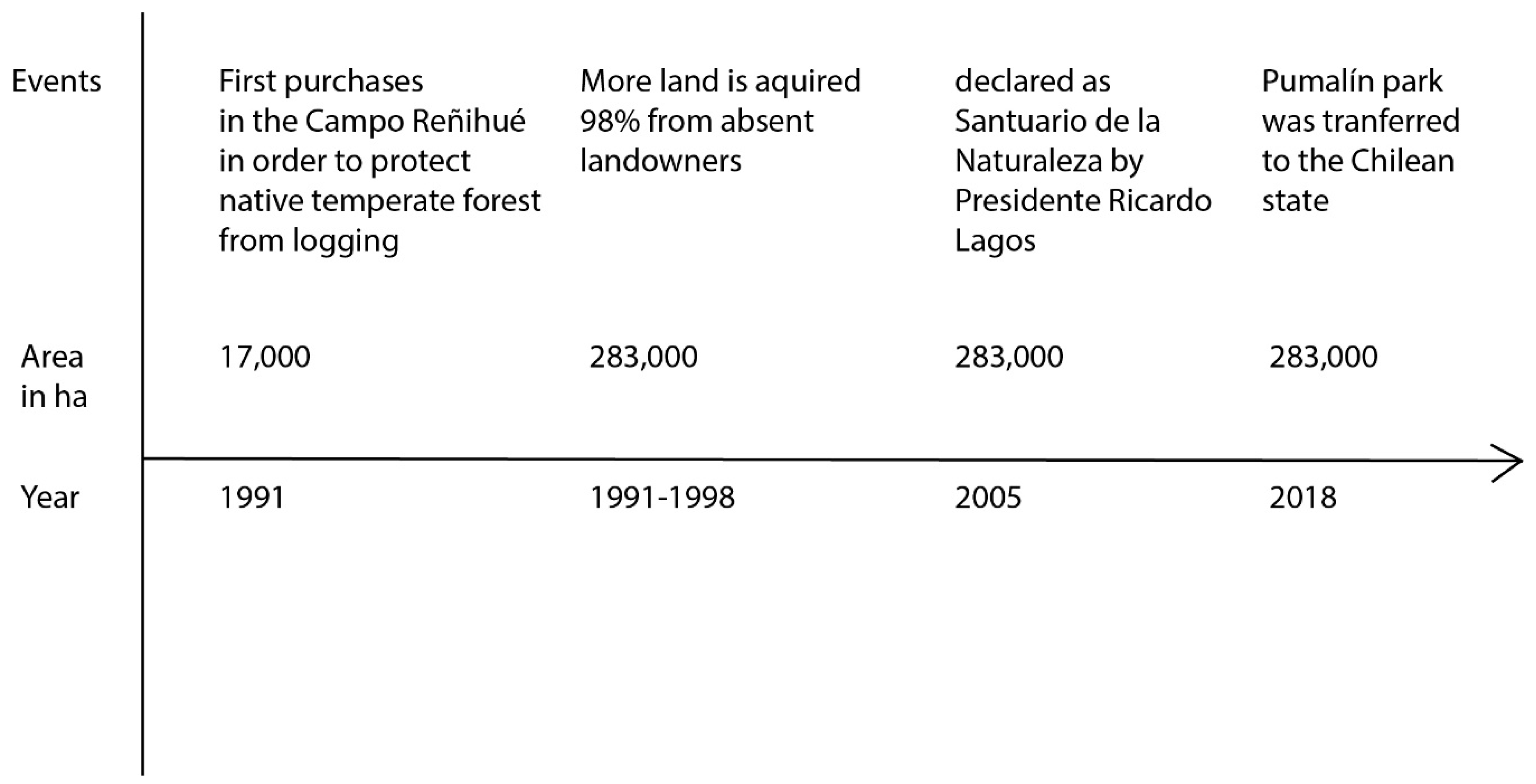

The Pumalín project began in 1991, when the American conservationist, philanthropist and businessman Douglas Tompkins bought a 17,000 ha plot of land in the Reñihué fjord, in order to protect native temperate forests at risk of being logged. Douglas Tompkins, who was a passionate outdoors man and founder of the North Face brand, visited Chile in 1963 the first time for mountaineering activities. The idea of creating a larger protected area with full public access grew over the 1990s. Therefore, an additional 283,279 ha of land was acquired, mainly, from absentee landowners. During this time the park infrastructure was created; camping sites, walking trails, information centers and other public facilities. The organization responsible for this was the Conservation Land Trust, with Douglas Tompkins at the helm [

11].

According to a CLT (Conservation Land Trust) report in 2002, US

$ 5,000,000 were invested in the purchase of the park. In 2000 the park received 12,700 visitors and annual operating costs were at around US

$ 1,000,000. The creation of Pumalín Park sparked a high degree of controversy in Chile. The process of acquiring a large amount of Chilean territory was seen as foreign intervention in national sovereignty by some political parties [

33].

The legal status of Pumalín Park has varied over the years [

34]:

7th of July 1997: An agreement was signed between Juan Villarzu, the Minister Secretary-General of the Presidency at the time and Douglas Tompkins.

26th of April 2005: Resolution No. 1.625, in which legal personality was granted and the statutes of the Pumalín Foundation and their amendments were approved.

19th of July 2005: Decree No. 1.137, designated Pumalín Park as a nature sanctuary.

288,689 ha of private estate named Pumalín Park ware granted legal status as a nature sanctuary by president Ricardo Lagos. Since then, the area is protected under the National Monument Law, which governs this category of protected areas.

Complementary to the park, the Tompkins Foundation has implemented different initiatives to diversify the productive activities such as sustainable pasture and cattle management, organic agriculture (e.g., meat, wool, berries, honey, and vegetables), also certified organic honey is produced and distributed under the Pillán Organics label, not only in the local market “Puma Verde” in Caleta Gonzalo, but also in Puerto Varas and also other cities throughout the country.

The most recent development that Pumalín Park experienced was its transfer from the Tompkins Conservation Trust to the State of Chile, taking place during an official ceremony on the 29th of January in 2018 with the former president Michelle Bachelet and Tompkins’ wife Kristine Tompkins. With this official act the creation of the Red de Parques Nacionales de la Patagonia Chilena was confirmed. Besides Pumalín Park, other private initiatives such as the Melimoyu Park and the Patagonia Park will be incorporated into the public national park system. All infrastructure, such as cafeterias, restaurants, camp sites, picnic areas, trails, signs and trail markers, staff houses, and other installations will be donated to the Chilean state. The investment in the two parks owned by Tompkins Conservation is estimated at US

$80,000,000 [

35] (

Figure 2).

Understanding the effects of private conservation on local development is still scarce in Chile. Only a few cases have been studied. This study aims to fill the gap between existing knowledge about the case studies (Rerserva Biológica Huilo, Parque Oncol, Valdivian Coastal Reserve) in the Los Ríos Region [

3,

8,

21].

Furthermore, the research aims to better understand the perceived effects of the implementation of Pumalín Park and its effects on the local development over the last 10 years on the town of Chaitén. The research questions of the paper are: What are the perceived effects of private conservation in relation to local and regional development? What are the advantages and disadvantages of the private conservation initiative to the local population?

2. Materials and Methods

To investigate how local people of Chaitén perceive Pumalín Park, and also how they value its contribution and effects on local development, the following methods were used: Firstly, a review of literature was carried out to find primary and secondary data to characterize the study area. These include topics dealing with conservation and its effects on the environment in a global, Latin American and Chilean context. Also, secondary data elaborated by the Chilean government, such as Census statistics, were acquired. These include the Census of 1992, 2002, 2011 and the most recent version in 2017.

Secondly, in order to gather primary data and conduct a survey to explore local perceptions of the park and its impact on local development, two visits to Chaitén and Pumalín Park were carried out in January 2017 and 2018. During these visits the following methods of social qualitative networks were used: (i) eight semi-structured interviews with stakeholders were carried out in order to seek their opinions on the following main topics: environmental, economic and social impacts and challenges of the Pumalín Project at the local level; also the future paths of the project’s development, considering its transfer to the Chilean state. Three of the interviewees were working for the municipality of Chaitén (the Secretary of Communal Planning, SECPLAN; one at Municipal Administration, one in the Pumalín project, the Director of Land and Mapping Program, The Conservation Land Trust-Chile and Conservación Patagonica), two were working in the accommodation business as well as two providers of tourist services in Chaitén. The interviews were recorded and transcribed for further analysis.

Furthermore, a questionnaire was applied to local inhabitants (

n = 82) in order to gather opinions that can be analyzed statistically using the Likert scale. Different types of questions were addressed, comprising three dimensions: economical, environmental and sociocultural. In total, 21 different questions were asked (

Appendix A). This questionnaire was applied in households, in the Junta de Vecinos (neighborhood council) and restaurants and cafés within the city of Chaitén. These places were located within 500 m of the main square. The southern part of Chaitén, which is now separated from the rest of the city, was not considered, because of its isolation. The households were selected randomly within this radius. In restaurants and cafés, the owners and local clients were consulted. People who had lived in Chaitén over the past 10 years and who were over the age of 18 were allowed to participate in this survey. The data was analyzed descriptively with Excel tools. The established method was based on a study with similar aims carried out on marine protected areas. In this research a mixed-method approach including interviews and household surveys were used in order to examine perceptions of local population living near a marine protected area in the Andaman coast of Thailand [

36]. The demographic and socio-economic characteristics of the 2017 Census of Chaitén correlate with the people who answered the questionnaire in terms of age and socio-economic status [

37]. Therefore, the results reach a high representability. Furthermore, the areas where the questionnaire was applied were chosen considering that people of all socio-economic groups of Chaitén could have been selected. The data was described using a univariate analysis. The questionnaire was administered directly.

82 people answered the questionnaire. 52 of them were female and 30 were male; the average age of the interviewee was 35 (the youngest interviewee was 18 and the oldest 62 years old). On average they had lived in Chaitén for 18 years (min 2 years, max 62 years). The formal education of the subjects was distributed as follows: elementary school: 20 people; high school: 36 people; university studies: 21 people. 5 people did not answer this question. The occupations were also inquired about. 15 of them were students; 36 were contracted workers; 14 independent workers and 17 housewives. These sociodemographic features correlate with the results of the Chilean Census of 2017. The census shows that 72.8% of the population is aged between 16–65. Therefore, the bias of the sample can be described as minor. Another small bias could be that the economically less dynamic part of Southern Chaitén was not considered. Another limitation of the survey is the gender bias present in the questionnaire because 52 (63%) of the interviewees were females and 30 (37%) were males. In the Census of 2017 59.5% were male and 40.5% were females.

Thirdly, the city was mapped using a map of Chaitén. This was necessary to show how tourism-related businesses returned to Chaitén after the volcanic eruption in 2008. Finally, in order to ensure the accuracy of the results, all collected data and information were analyzed and triangulated; this method allows the mixing of data or methods so that diverse viewpoints cast light upon a topic [

38].

Research Area

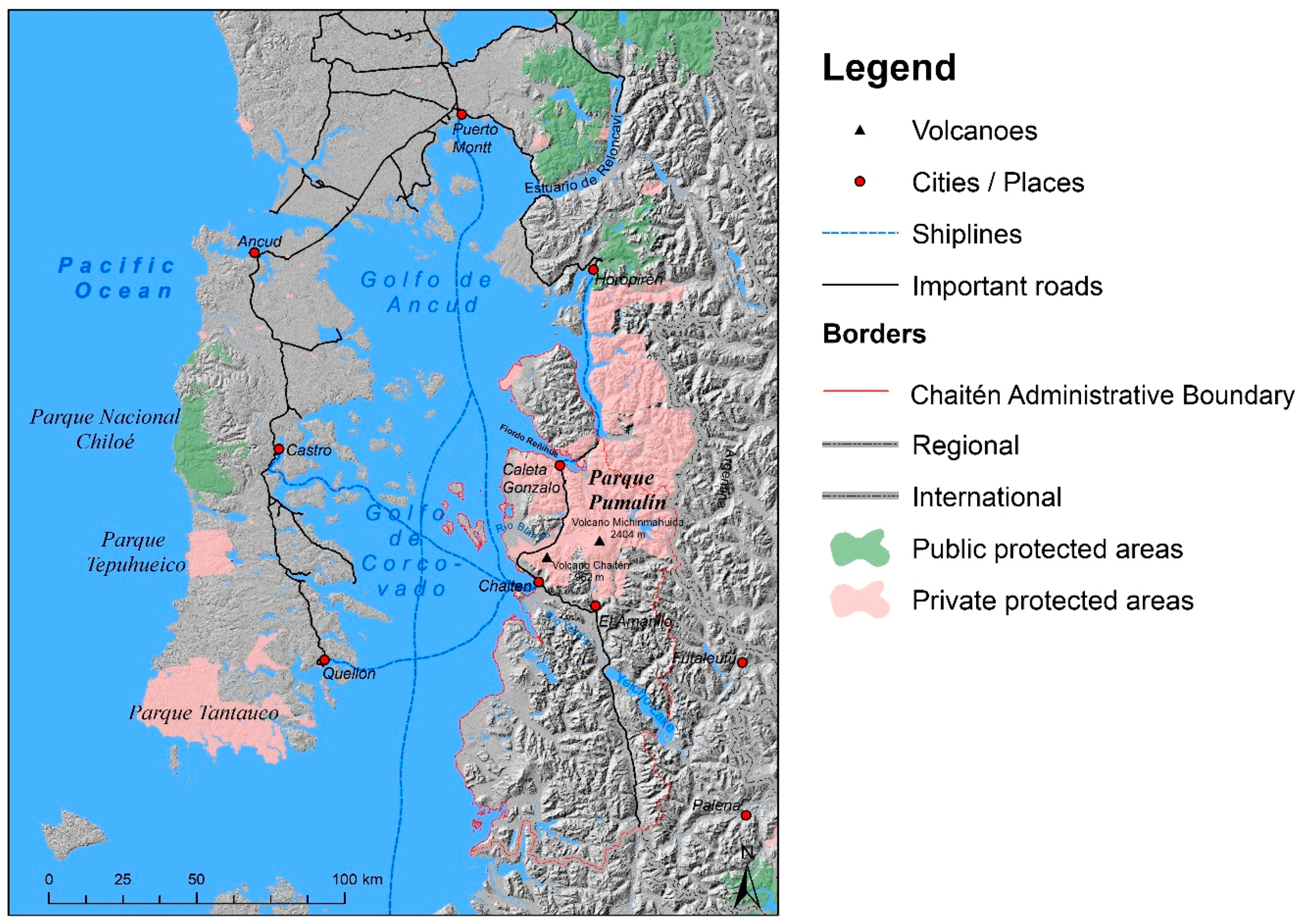

The area where Chaitén is now located (

Figure 3) was not permanently inhabited during the 19th century; the place is also called Chiloé Continental or Palena. In 1905 the first settlers arrived at the future location of Chaitén when the Chilean Navy determined that the area was suitable for an inland road connection. In 1921 three people from the archipelago of Chiloé built homes for themselves. They were fishermen and loggers [

39]. In 1933 another settler arrived and by 1940 Chaitén was officially established as a city and municipality [

40].

In the ensuing years Chaitén served as the main transportation hub to places such as Futaleufú and Palena. The Yelcho river was a channel for boats going to Yelcho lake, the Puerto Cardenas port and from there on to Puerto Ramírez on the other edge of the lake. From there on the villages of Futaleufú and Palena were reached by horseback. From 1946 onwards, the Chilean army established the “Cuerpo Militar de Trabajo” near the city of Chaitén, with a workforce mainly from Chiloé, [

39] who built a road connection from Chaitén to the Yelcho lake. In the 1980s the construction of the Carretera Austral (Austral Highway) began. This meant an improvement in connectivity and an increase of traffic, tourists and cargo [

40]. In 1991 Douglas Tompkins bought plots of land near Chaitén and began his private conservation initiative [

10].

The eruption of the Chaitén volcano in 2008 constituted a major interruption to events. On May 2nd a Plinian eruption took place in a volcano that was assumed to be extinct. The entire population of about 5,000 residents were evacuated to a security radius of about 30 to 50 km away from the volcano on 4 May and 5 May. On May 12th Chaitén was affected by a lahar. The economic loss consisted of around US

$12,000,000 in public buildings alone, which were insured. Clouds of ash shut down regional airports and forced the cancellation of hundreds of domestic flights and several international flights in Argentina and Chile [

41]. The river Chaitén cut the town in half. From that point on, the southern part of the town became isolated. Most of the houses were destroyed due to the weight of the ashes, which rained down on the rooftops.

In the years after the eruption and evacuation, the whole place was abandoned and property was seized and taken to into government hands. After a few years of uncertainty many former inhabitants returned to Chaitén. At first, they came spontaneously and were unorganized. Then in September 2010 authorities announced that Nueva Chaitén was to be re-established on the same site, and would become the new capital of the municipality of Chaitén. In March 2011 basic services, such as drinking water and electricity were re-connected. After that, a master plan for the resettlement of the village was undertaken [

42].

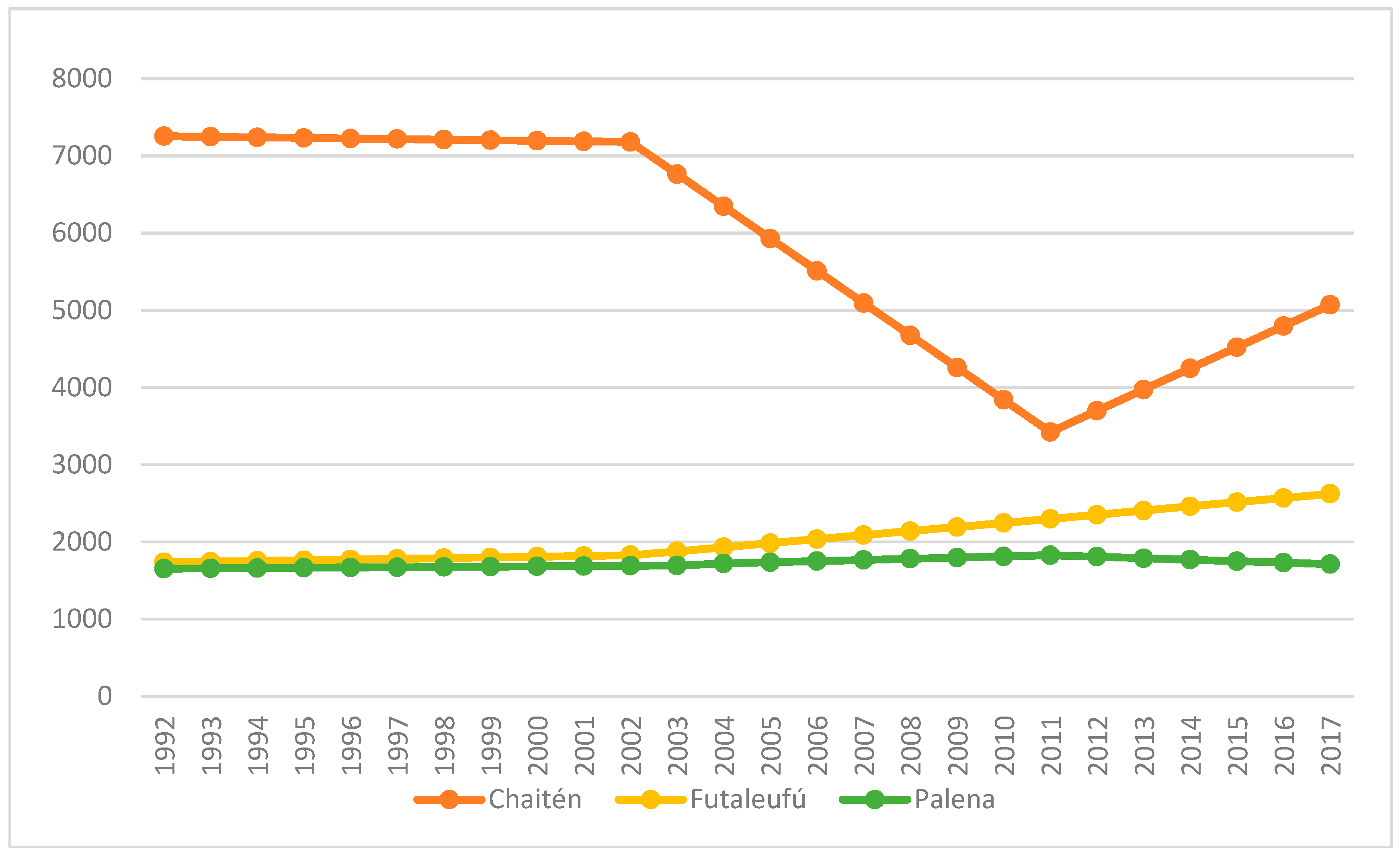

The population of Chaitén had stabilized during the 1990s. In 2002, 7,182 people lived in Chaitén, the majority in the urban area. Other populated areas are Santa Lucia, El Amarillo and Santa Barbara. Due to the volcanic eruption in 2008 Chaitén was completely evacuated and depopulated because of health and security concerns. Nevertheless, according to the recent census of 2017, 5,071 people live in Chaitén (

Figure 4) and the population density is 0.6 hab/km², constituting a normal density for the south of Chile [

43].

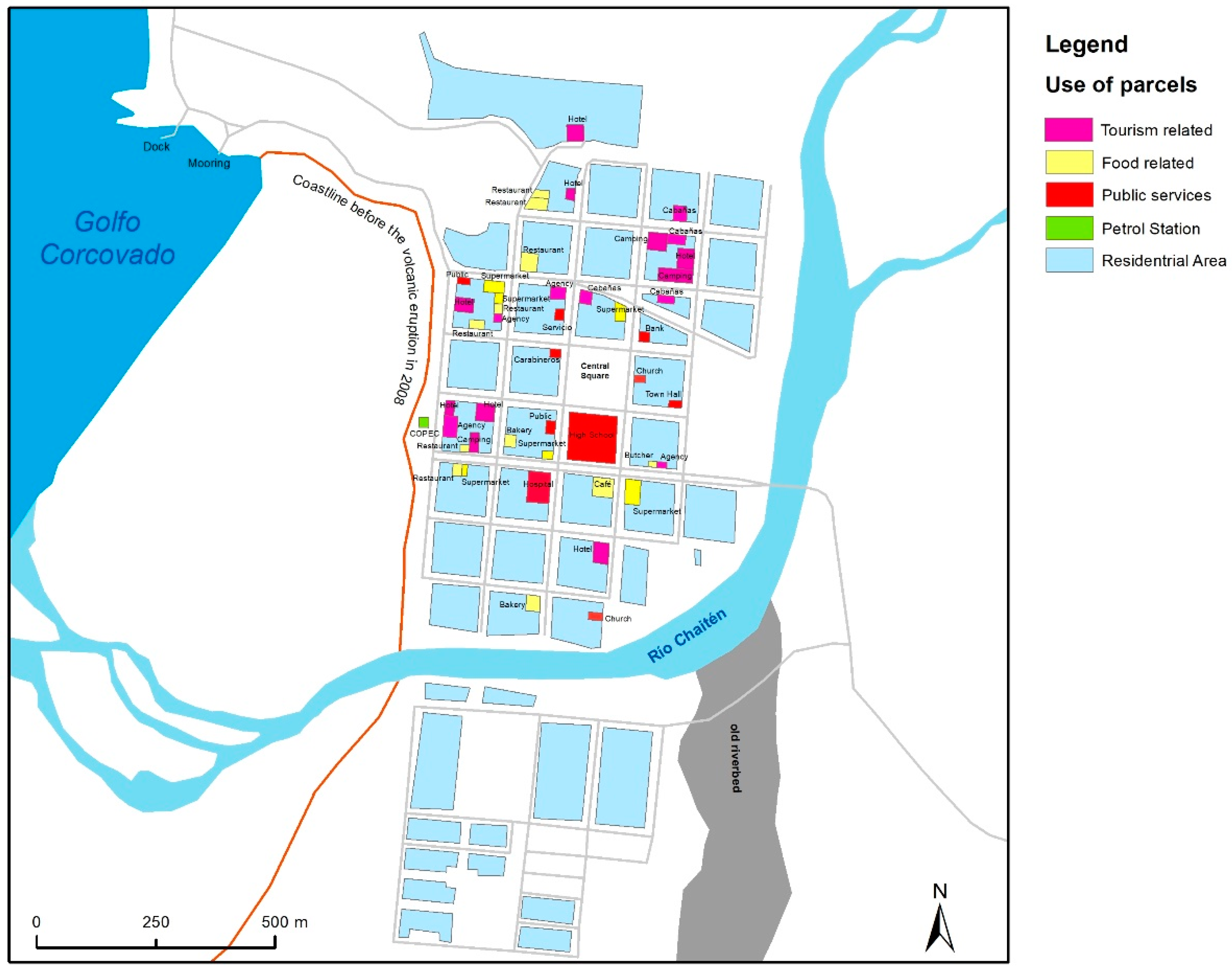

Nearly 68% of the pre-disaster populace has returned. Over recent years tourist operators have returned, restaurants are opening again, there are four different camp sites and hostels, cabins, as well as restaurants and cafés. Furthermore, there are banks and tourist agencies (

Figure 5). They are mainly for purchasing tickets for the ferries and busses. Also, you can buy day-tours to Pumalín Park, which can be visited through different entrances. Therefore, it can be stated that Chaitén once again offers good services to tourists and locals. The prices are comparable to other places in Continental Chiloé. In contrast, the neighboring communes did not see a decline in the population because of the volcanic eruption. However, they were affected by traffic constraints and isolation. Their main access roads were through Argentina during these events.

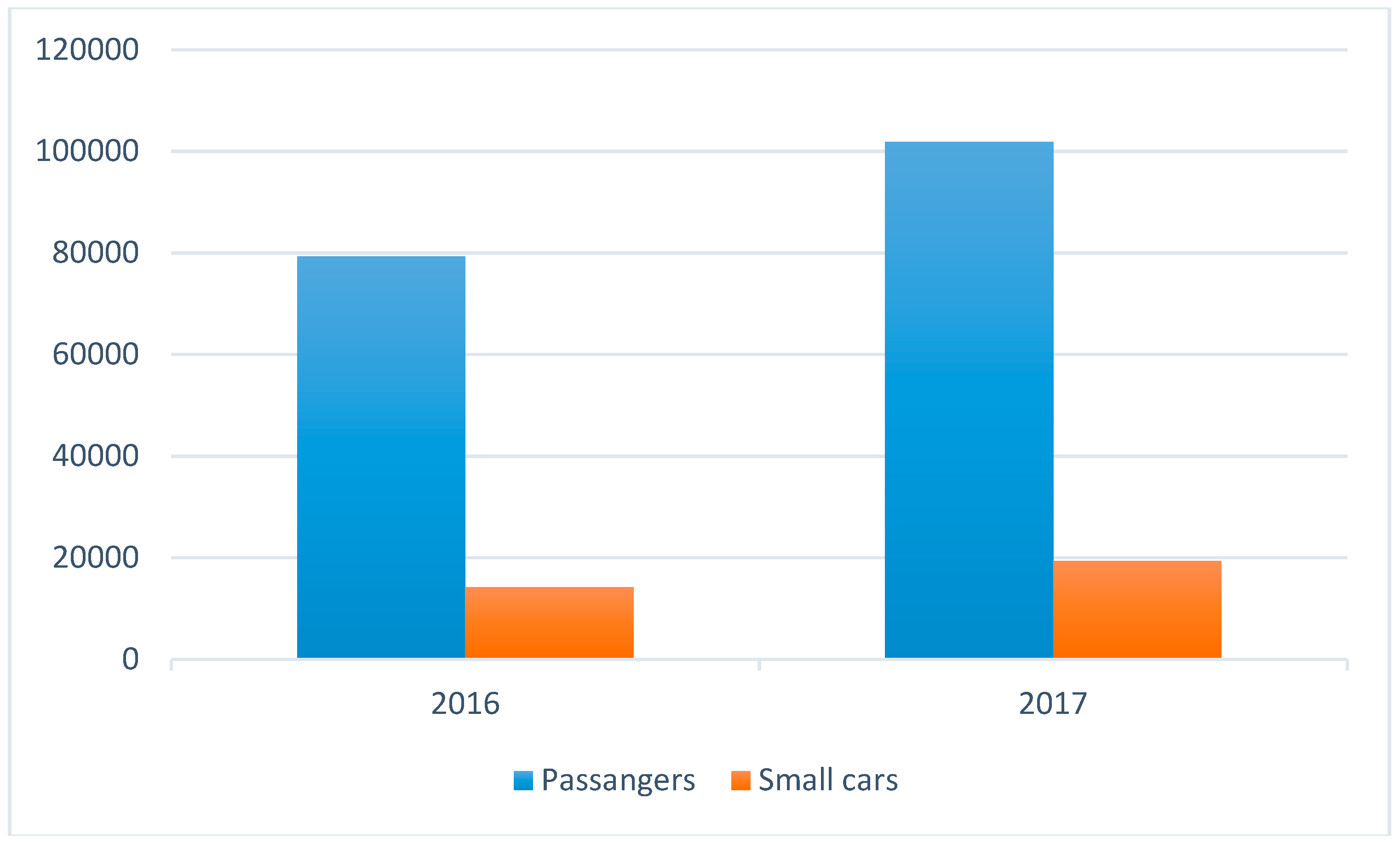

Data from the Naviera Austral shipping line, connecting Chaitén with the rest of Chile, shows a significant increase of passengers over recent years in all connecting routes (Puerto Montt -–Chaitén, Quellón–Chaitén and the Ruta 7 Bimodal). In the high season months of January and February there were 79,268 passengers and in 2017 there was a movement of 82,071 on all three connections combined. The Ruta 7 Bimodal has the highest rate of movement of all three connections. In

Figure 5 the increase of passengers and small cars transported on these combined routes is displayed.

3. Results

3.1. Pumalín Park Catalyses the Local Economy

A large majority of the

Chaiteninos agreed totally or moderately that Pumalín Park has helped the region with its developing tourism industry (40% and 45%) (

Table 2). With 38% and 36% agreeing totally, people still highly agreed with the question: Is Pumalín Park able to improve economic activities which are not related to tourism, such as services, handcrafts, fishing? The results show that the vast majority of the people living in Chaitén see Pumalín Park as economically very positive. The statement, as to whether Pumalín Park was able to attract other investments to the region, was also agreed with by a majority (28% agreed totally and 34% agreed moderately).

These results coincide with the vision of the local government, which states in the master plan that tourism is an opportunity for the economic and environmental development of Chaitén, because of the wealth that tourism generates, the possibilities of articulation with other productive activities, and its potential to increase the participation of local population in this activity. The great potential of the commune makes it a quality tourist attraction, ready to position itself at regional, national and even international levels. (Municipalidad de Chaitén 2016). An interviewee working in the municipal administration said: “The park has been a key factor to activate the economy after the eruption of the Chaitén volcano.” Furthermore, the Report for the Reconstruction Plan in 2009 recognizes Pumalín Park as a strategic actor on a regional level. However, specific recommendations are not mentioned [

45].

Nevertheless, the difficulty in coordinating long-term actions between the private sector and local government is considered a challenge that should be addressed, and the creation of a public-private coalition to support tourism as a key activity within the commune is a priority. Important action was taken in 2015 when the National Service of Tourism (SERNATUR) developed a program to enhance the formalization and registration of tourist services, the implementation of a promotion and marketing plan, and a mechanism to facilitate technical assistance to identify new attractions in the area and other types of tourism activities. The program was geared towards working with the Chamber of Tourism of Chaitén and the Chaitén Tourism Corporation. In 2017, the process to declare the commune as ZOIT (Touristic Interest Zone) began, bringing new opportunities for investors and local entrepreneurs.

The map in

Figure 6 shows the services generated in Chaitén for locals and tourists. Tourism-related services such as accommodation, agencies and high-end restaurants have re-emerged in Chaitén. As a transportation hub for the Carretera Austral, Chaitén has different agencies specializing in boat and air tickets as well as bus connections to places further south.

To the question inquiring if Pumalín Park was more important than the Chilean state as the driver of employment, the majority disagreed or were indifferent (19% total disagree, 16% disagree and 43% indifferent). This opinion can be explained because the Chilean state is the biggest employer in this peripheral region; around 25% of the employed people in the commune work in public service (Municipalidad de Chaitén 2016). This includes administrative work in the municipality and road construction; for instance, maintaining the Carretera Austral and CONAF (Corporación Nacional Forestal), the recently opened office of SERNATUR (Servicio Nacional de Turismo) among others. Furthermore, the police (Carabineros) and the military are important employers. These jobs are stable and have annual contracts, while the tourism sector has a high seasonality, due to the short summer season in Patagonia (December to February). An interviewee working in municipal administration confirmed this observation.

Finally, a quote by an administrative worker in the municipality emphasized the good relationship between the city of Chaitén and Pumalín Park:

“The Pumalín Park has been a key economic factor for the city of Chaitén after the eruption and the aftermath of the Chaitén volcano. Without the employment and services generated by the park, the recuperation of the town would have been much slower or impossible”.

3.2. Pumalín Park Has Helped Conserve Valuable Native Forests

Different questions concerning the environmental impact of Pumalín Park were asked (

Table 3). 72.5% agreed totally and 17.5% agreed moderately with the question: Has Pumalín Park contributed to the conservation of flora and fauna?” The same percentages were received to the question: Has Pumalín Park contributed to conserve local landscape? This high agreement of the

Chaiteninos can be explained due to the fact that the area’s native flora and fauna, now under protection of Pumalín Park, was under permanent threat of land use change. These include logging of endangered native trees such as the Alerce “

Fitzroya cupressoides”, which can still be found in Pumalín Park [

46].

In El Amarillo, where the main southern entrance of Pumalín Park is located, the Park administration has given financial and logistic aid for the beautification of residential houses. Additionally, El Amarillo has a store selling local products for tourists run by the Pumalín administration. This small place some 25 km east of Chaitén had perfect conditions for developing a small-scale tourist economy and visitor infrastructure. When the volcanic eruption shut down the city of Chaitén, the Pumalín administration decided to move their offices to El Amarillo. This has led to an upgrade of the housing structure, especially the facades. From El Amarillo there is a view to the Michimahuida Volcano and the Tabiques Mountians. The community of El Amarillo is working with the Pumalín Project to launch a variety of renewal efforts.

It is also important to mention that the good reputation of the Pumalín Project in environmental issues is a result of the crucial role that Douglas Tompkins and the Pumalín Foundation played in 2006 against the construction and implementation of the hydroelectric megaproject Hidroaysén in the Aysén Region. The campaign was called “

Patagonia! Sin represas!” (Patagonia without dams!), which advertised against the project [

47]. The construction of 5 dams would have generated a total of 2750 megawatts (3,690,000 hp) with further capacity for 18,430 gigawatt-hours (66,300 TJ) on average annually. The projected cost was estimated at US

$32 billion (1.5 trillion Chilean pesos), making it the largest energy project in the country’s history, but it would also have flooded 12,500 acres of pristine territory that is increasingly popular as an ecotourism destination and it would have affected Pumalín Park with the implementation of the transmission line. However, the tough opposition of different sectors, such as environmental groups (e.g.,

Patagonia sin represas), NGOs, international experts and the national community helped to stop it. In June 2014, the project was rejected by the Chilean government due to its alleged environmental impacts (BBC 2014). Seen from a Chilean national interest perspective and their demand for clean energy and developing the Aysen region economically, the alternative to stopping these hydroelectric projects can be challenged. In 2008 only 18.3% of the hydroelectric potential of Chile was harnessed and in the Austral region, where the project would be located, only 0.2% of the area is used [

48].

An astonishing result was observed to the question: would the transition of Pumalín Park to the Chilean state be a threat to environmental conservation? Here a majority of 45% agreed totally and a 10% agreed moderately. Only a minority of 20% disagreed and 7.5% totally disagreed that the transfer to the Chilean state would not be a threat to conservation. This reply can be explained by the fact that the people of Chaitén do not believe that the government of Chile is able to maintain the same quality of conservation and infrastructure as Pumalín Park is doing today. In fact, according to [

49], the land that Tompkins donated has an annual maintenance cost of close to

$600 million of Chilean pesos, a budget that must be assumed by the Chilean state to protect and care for the areas in an appropriate manner. The infrastructure of Pumalín Park is of high quality, especially the camp sites and their sanitary infrastructure. Furthermore, Chilean National Parks are often challenged with border problems and land use conflicts [

14]. On average in Chilean National Parks this kind of infrastructure cannot be found at these low prices. Therefore, people fear that the quality of the park infrastructure could decay. In 2018 it cannot be foreseen how the new administrators of the park will cope with this challenge.

3.3. Pumalín Park Has Promoted Local Culture and Environmental Consciousness in the Area

The last section of the questionnaire asked the

Chaiteninos about the sociocultural effect of Pumalín Park (

Table 4). They were asked if Pumalín Park has contributed towards placing further value on nature and the local environment? A large majority of the

Chaiteninos agreed or agreed moderately (46% and 22%) with this question. This can be seen as evidence that Pumalín Park has shaped local identity since its foundation. Different initiatives have helped improve the natural landscape and cultural heritage in the area, for example through the promotion of environmental education projects or fostering the discussion among the local population on the importance of environmental conservation.

A person working for Pumalín Park emphasizes the sociocultural dimension: “Before the park was implemented the majority of the local population had no consciousness of the valuable flora and fauna nearby. Before the park was implemented most people in the region saw the forest mainly as a source of lumber and firewood and there was no sustainable forest management.”

In the beginning, in the 1990s and 2000s, many locals and Chilean politicians were skeptical about the project [

50], because private conservation was something new and for some people this kind of protection initiative was considered an obstacle to economic development of the region and a threat to national sovereignty. Today, the park is well integrated in the region and the local people have a positive view of Pumalín Park. In the interviews with the different stakeholders in the public administration and the private sector the same positive opinions about Pumalín Park were stated.

The questionnaire also asked if Pumalín Park had positive impact on public knowledge of the area. Here a majority of 40% agreed totally and 28% agreed moderately. Furthermore, it was aske, whether Pumalín Park had contributed to enhancing the natural and cultural heritage of the area. Also, the vast majority of the

Chaiteninos replied positively to this question. (46% agreed totally and 22% agreed moderately). The person associated with Pumalín Park stated that, before the Park was implemented, the region had no tourist attractions nearby. After the volcanic eruption, the park helped to re-establish the region, as it provided work for the people of Chaitén and the neighboring communities. All these efforts have been recognized by international organizations. In January 2018, the Chilean government received the Conservation Visionaries prize from the International Land Conservation Network, because of the implementation of the Red de Parques de la Patagonia National Park. This grants the region a high visibility and international recognition might attract more visitors into the region [

51].

4. Discussion

The research concentrated on the issue of private conservation and the perceptions of the local population. Conservation can have strong effects on the neighboring population depending on their economic participation and the social acceptance of conservation. Other studies [

32,

36] show different results concerning the perception of nearby communities. Depending on environmental awareness, and participation in management and services, the acceptance can vary significantly. Furthermore, those studies show that younger people and those with higher income are more accepting. Studying private conservation in Chile is of particular interest because of the significant increase of private protected areas in the last three decades. Chile has a share of 2.2% privately conserved land, in contrast to 18% of the territory that is protected in National Parks [

14]. The phenomena of private conservation and effects on regional development has already been investigated in the Los Ríos region in the Parque Bíologico Huilo Huilo, Parque Oncol and the Valdivian Coastal Reserve [

3,

8]. In these cases, it was shown that private administrators see local people as threats to forest conservation goals. However, it was also shown that private conservation enhances self-governance through education programs. The economic shift from forestry industry towards eco-tourism is a significant economic transition on a regional level for the cases in the Los Ríos region. The findings suggest that social impact and consequences of PPAs facilitating ecotourism should be given the same level of attention that was given to the public protected areas. Pumalín Park represents a unique case which differs between the already existing case studies in Chile. The transition was not from forestry but from existing native forests, mainly Valdivian rainforests. In contrast to other cases, Pumalín Park is a key economic factor for Chaitén; without its existence the recuperation from the volcanic eruption would have been far more difficult. 45% of the local population agreed that the park helped develop the tourism sector in the region. This seems obvious, as without the park and its services the attractions would be minor. To the question: Is Pumalín Park, and not the Chilean state, the main motor of employment? People reacted indifferently to negatively, because the majority of the people in Chaitén mainly work in public services. In other cases, such as the Reserva Biologica Huilo Huilo the situation has no easy comparison, because the population structure is different. In the case of Huilo Huilo most of the nearby inhabitants extracted timber before the area was transferred to private conservation. As to whether Pumalín Park should become a state park, the local population were mainly skeptical. The population referred mainly to other parks run by the semi-private CONAF (Corporación Nacional Forestal), which from their point of view has lower qualities in conservation and service. The stakeholders share this point of view. This can be interpreted as a critique on the National Park system in Chile, which tends to be underfinanced.

In general, it can be stated that Pumalín Park has a strong positive influence on local development. However, the status quo of private conservation remains uncertain, because of the planned transition of the park into the National Park system. Therefore, a comparative study in the future would allow new insight of the perception by the people after the transition.

5. Conclusions

The case of the Pumalín Project is a good example of how a private protected area can help shape the development of a region, and also contribute to parallel economic activities. In 1991 when Douglas Tompkins started with this idea, private conservation and activities such as ecotourism were something new and strange, especially in a country where economic growth was seen at that time as the only way to achieve the goals of development and to fight poverty. Results of the investigation show that 27 years after the implementation, it is clear that Pumalín Park has changed this paradigm and other possibilities for development arise as opportunities for rural marginalized areas that are rich in nature and cultural landscapes such as the Patagonian fjord lands. The various initiatives developed by the Tompkins Foundation over this period have shown that nature conservation and economic well-being can coexist without restricting the local development.

Furthermore, the findings of this research have shown that the park is perceived both by the local population and stakeholders as a contribution to the town of Chaitén, especially after the volcanic eruption in 2008. The Park is considered to be a relevant territorial actor in many official documents and also in the reconstruction plan of the city; the municipality recognizes that improved articulation between private initiatives and the local and regional level are necessary in order to finish reconstruction.

In interviews with local stakeholders and questionnaires with locals, the vast majority of the people shared the view of the positive impact of private conservation in their region. In this case, it can be seen as one of the key economic stimulators in the region, besides public services in road construction and administration, among others. The majority of the local population does not wish for the integration of the park into the National park system. They argue that the high quality of the infrastructure would decrease in this case. Further studies to observe future developments could give insight into this transition.