3. Cultural Management in Korea

3.1. Cultural Background of Korean GIAHS

The history of Korean GIAHS is not long. In 2014, the first KIAHS, Korean Important Agricultural Heritage System, of Cheongsando Gudeuljangnon as “Flat Stone Floor Paddy Field System” in Wando Island, Jeollanamdo Province, and the second KIAHS of Jeju Batdam as “Stone Fence Agricultural System in Jeju Island” were designated as first Korean GIAHS sites by FAO. Subsequently, the “Traditional Hadong Tea Agrosystem, Hwagae-myeon” was also designated as the third Korean GIAHS site in 2017. In Korea, KIAHS is managed and designated by MAFRA (Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs) of Korea [

17]. The first two designated GIAHS sites of the Islands of Cheongsando and Jeju are both located off the southern part of Korea in the Korean Peninsula. In relying on reasons why those two islands were designated, we can find the culture and history inherent in Korea.

Gudeul means the typical Korean cultural expression of

Ondol, the underfloor house-heating system, and Batdam in Jeju Island is also called

Heuknyong-malli, meaning the longest black dragon. Moreover, Jeju Island has been acknowledged as the site for a set of outstanding natural and cultural landscapes, resulting in further global designations, including UNESCO Biosphere Reserve (2002), UNESCO Jeju World Natural Heritage (2007), UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity: Jeju Chilmeoridanggut (2009), UNESCO Jeju Island Global Geopark (2010), UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity: Jeju HaenyeoCulture (2016) and FAO GIAHS Jeju Batdam Agricultural System (2014).

About 2.77 million people, or 5.5% of the total Korean population, depend on farming and their staple food is rice. Rice provides the greatest income within the Korean farming structure, contributing around 20% overall according to the survey conducted by Ministry of Government Administration and Home Affairs of Korea in October 2017. Korean agriculture can be separated into rice paddy farming and dry-field farming. As of 2017, KIAHS sites of the rice paddy farming system include “The terrace paddy fields, reservoirs, puddles and irrigation ditches”, and of the dry-field farming system includes “The Batdam Agricultural System”, “Terrace Tea Plantation”, “Sansuyu (Cornus officinalis) System”, “Ginseng Agricultural System” and “The Bamboo Forest System”. The cultivation of rice in Korea stretches back over 2500 years ago, with rice seeds aged from 12,500 to 13,920 years ago being discovered, thus indicating the origination of Domesticated Rice in the Korean Peninsula.

3.2. Cheongsando Gudeuljangnon and Jeju Batdam Agricultural System

Cheongsando Gudeuljangnon (Flat Stone Floor Paddy Field) System in Wando Island, Jeollanamdo Province is the utilization of a similar traditional system of the traditional

Ondol floor heating system which is utilized to even support rice cultivation, and overcome the given disadvantageous natural environment. Ondol is the typical Korean culture of the underfloor house-heating system to keep the floor warm by blowing heated air from the kitchen (

Figure 4a). In Cheongsando, the irrigation structure is built by placing the water path in the pebble layer under the Gudeuljang floor just like Ondol. Then, the system is covered with mud and soil to manage the water retention level and temperature controlling. The irrigation water flows under the fields, as heated air flows under the floor in an Ondol house. “Gudeuljang” means stone layers of Ondol and “-non” means rice fields in Korean. The uniqueness of Gudeuljangnon is the stone built lower part, showing the collaborations among the Korean traditional and cultural Ondol floor system for dwellings and agricultural irrigation system. With the system, the land use level was maximized and any lands in the island could be utilized either for rice paddy or dry field farming by water level management. The significance of the system is that the continuous-flow irrigation system of the rice paddy has developed through the water passing from the top down then to the lower part of a circulation system. The system has served its role as the function in eco-corridors, providing soundscapes for irrigation water which allows various species by connecting nearby forests and rice paddies.

The second KIAHS of Jeju Batdam (Stone Fence) Agricultural System includes the 22,000 km long stone fence structure around most dry fields on the island (

Figure 4b). The volcanic Jeju Island has been culturally known as “The Island of three abundances and three non-existences” [

19]. The three abundances of Jeju mean women, wind and rocks, while three non-existences are believed as no thieves, no gates and no beggars. Most of the soil of Jeju Island is covered with basalt rocks with the highest degree of water permeability. In turn, this means the land conditions are unsuitable for ordinary farming. The average depth of cultivated soil is shallow at about 18.3 cm, and up to 40% of the soil is filled with pebbles. As a result, the barren environment has not been generous for either people or farming for food security and supply, with productivity further impacted by the incoming harsh winds that persist all year around. During the Joseon Dynasty, Jeju Island had used as a site to relocate political exiles due to its remoteness and inaccessible location and this led to the birth of Batdam Agricultural System of Jeju. As the entire Jeju Island has been covered with volcanic rocks, people had to remove the pebbles and rocks out of their lots to produce vegetables. The high draining feature of the island soil made farming most difficult. The strong winds kept knocking down crops even before their rooting takes part. Therefore, the forefathers started to utilize the rocks and pebbles in their lots which they had to remove. Then, with this resource, they built walls around their small pieces of land to soften the winds and act as windbreaks to prevent further soil losses, retain the moisture and increase the temperature of the areas, in addition to block off trespassing by horses and cattle. In addition, the wall also functioned as the primary indicator of the property boundary.

With little arable land available, ancestors of Jeju Island had to create a different culture of inheriting to the custom expressed on the Korean Peninsula. Most Korean assets were usually passed down only to the oldest son as the heir, but on Jeju Island, the inheritance divided up the land amongst all of the sons from the family. Naturally, parental concern was paramount for those children who were due to inherit down with much smaller size arable land on Jeju Island. Each child’s living in this barren environment depended on their forefathers’ inheritance system, and consequent of this issue many old pictures of the island show off the smallest arable land size. Most daughters were also given a minimum plot of land from which to live and survive off. Again, different from the practice on the Korean Peninsula, some daughters can also be included as the heirs of the family on Jeju Island. As a result, this practice has been one of their cultural foundations of “equality” in Jeju’s agri-culture. People call it as “Suneuleum”, meaning chip-in help or extend help for others.

With the stone walls around the dry-fields, farmers were able to produce vegetables including carrot, potato, garlic, radish, cabbage, barley, mugwort, buckwheat, and others, but not rice. The cultivated fields are relatively small and come in all sorts of shapes reflecting the cultural backdrop. Because of the field size and shape, no machinery was adapted in Jeju agriculture, hence they could produce the most organic crops in the best natural condition. With that background history of Jeju agriculture, Jeju agro-products and diet are recognized to be most healthy now.

3.3. New Movements for Agro-Cultural Trials in Jeju Island

Jeju’s multi designations of UNESCO value could be discussed for various reasons. Jeju Island currently honors five UNESCO values and recognitions which are listed in

Section 3.1. The local government of Jeju has devoted its full capacity to promoting Jeju’s environment, culture, and landscape values throughout the world earlier even before it gained its first UNESCO title in 2002. Since then, the resident islanders have been supportive and gradually recognized the value of UNESCO titles. Jeju is often referred to as the only multi UNESCO titles region, and many visitors also state that. Such situations might impinge positively on islanders’ way of thinking or their identities.

Recently, The Batdam Agro-Culture Research Team of the Research Institute for Regional Government and Economy of Korea (Korea RG & E) in Jeju has published a couple of books on Jeju Batdam Agro-stories focused on Jeju’s agro-culture and dynamics of culture. Since the designation of Jeju Batdam Agricultural Heritage System, many farmers’ family stories, histories, cultures and community activities along with their concerns and the role of Batdam for the future have been interviewed by various local news media. One of the local’s worries is the fading of traditional culture due to upcoming developments which result in a loss of small local farmlands that used to sustain ordinary farmers’ lives and their associated stories. It is further felt that the memories, Agro-stories and culture of the farmers in earlier generations must be recorded and shared for the benefit of future generations.

GIAHS’ Jeju Batdam Agricultural Heritage System was also presented during the Gil Exhibitions (Gil means a road or path in Korean) in Jeju in October 2017, where many visitors and residents of Jeju Island attended. The outcome was deemed successful, as more than five hundred visitors stopped by the Jeju GIAHS desk, and about a hundred participants joined the field trip. Most participants showed great interest in getting to know how local people survived the given harsh living environment, and how their culture was suiting their needs in the old days. Participants were invited for walking and exploring with researchers along the segment of Batdam as a field trip, introduced to the variation of Jeju crops, history of trading rice with their vegetables, and the stories of the birth and functions of Batdam. Following the participants’ positive responses and remarks for the content of GIAHS Batdam, the research team has decided to expand and develop further Agro-stories around Batdam all over Jeju Island in the near future.

4. Cultural Management in China

4.1. Cultural Problems in Chinese GIAHS

China was one of the first countries that responded and actively participated in the protection of agricultural heritages. In 2005, Qingtian Rice–Fish Culture System in Zhejiang Province was launched as the first GIAHS in China, which officially begins the conservation of agricultural heritage systems in the country. After more than a decade of exploration and practice, China’s agricultural heritage designation and conservation has achieved fruitful results. As of October 2017, China’s GIAHS sites rank first in the world with 11 out of the global total of 39 GIAHS sties. In addition, China also established a China Nationally Important Agricultural Heritage Systems (China NIAHS) project to conserve the agricultural heritage at the national level, which now has 91 sites on that list. The overall goal of the GIAHS and China NIAHS program is to identify and safeguard GIAHS sites and their associated landscapes, agricultural biodiversity, knowledge systems and culture.

Culture is a significant part of GIAHS sites, as mentioned in

Section 1.2, which is one of the main differences between traditional and modern agriculture. Culture, including values, traditions, behaviors, relationship, etc., has played an important role in maintaining the order of agricultural activities, adjusting interpersonal relationships and the relationship between human and nature. Most of the GIAHS sites in China are located at economically limited and ecologically fragile areas, some of them were even isolated from the outside for hundreds of years, but with well-preserved unique farming methods and traditional cultures. This is particularly the case in regions with significant ethnic-minority populations. However, after being designated as GIAHS sites, the agricultural heritage systems and the related rural area have also been acknowledged worldwide.

Although the study of GIAHS has received great enthusiasm and support from related governmental departments and research institutions, agricultural heritage is still a new concept with a lot of gaps needing to be filled, especially in the field of cultural studies. The previous study of GIAHS was mainly concentrated on the “nature” aspect: biodiversity, ecology, ecosystem services, climate change, etc. Indeed, culture was mentioned, but mostly connected to the studies regarding tourism potential and development. The true value of culture in GIAHS has been underestimated and the cultural related problems during the GIAHS conservation progress have been ignored.

Section 4 discusses some cultural related problems that happened in the GIAHS sites in China.

4.2. The Effects of Tourism on Ethnic Culture at GIAHS Sites

Although we follow the concept of culture from UNESCO ICH in

Section 1.2, culture can also be defined as a way of life and a system of values and beliefs which is a creative, recreational practice [

20]. It can be conceptualized at various levels including national and sub-national, incorporating groups such as ethnic peoples [

21]. Ethnic means very strongly bounded homogenous cultural identities, firmly associated with a particular homeland and rooted in strong kinship ties, sometimes equal to people whose common physical characteristics are believed to make them socially distinct [

21,

22,

23]. Ethnicity and its associated cultural manifestations are major tourism assets and are often marketing themes for many cultural and agri-cultural heritage sites [

24]. However, in most situations, the excessive commercialization threatens the authenticity and sustainable development of the destinations.

Tourism gradually becomes the fastest growing and most profitable industry in many rural areas, also in China, which provides opportunities for economic development and enables interaction between local people with outsiders. In the rush to develop their local tourism industries, many local government authorities at the GIAHS sites, especially in the economically challenged areas, are now actively developing their tangible and intangible cultural assets as a means of developing comparative advantages in an increasingly competitive tourism marketplace [

24]. Nevertheless, the dramatic development of tourism can also cause irreversible damage to the indigenous culture [

25]. In the face of globalization, the uncontrolled tourism development at unprepared places can cause irreversible deterioration of their native culture, natural environment and local society.

Indeed, many of the GIAHS and China-NIAHS sites are located in the minority areas, such as Congjiang Dong’s Rice-Fish-Duck System created by Dong people and Honghe Hani Rice Terraces Systems created by Hani people. Dong and Hani ethnic groups are two of the 56 ethnic groups officially recognized by China, who mostly live in Guizhou, Hunan, Yunnan and Guangxi Province in China. The ethnic culture and unique traditional farming methods provide strong cultural identities to these sites, which made them important actual or potential tourism attractions. With the strong cultural characteristics, some of these places and some of the cultural activities in the places have also been designated as World Cultural Heritage (WCH) and Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH). For example, the Honghe Hani Rice Terraces System is both a GIAHS site designated by FAO and a listed WCH by UNESCO; the Grand Song of Dong Ethnic Group has been inscribed as an ICH in 2009. Hence, culture, especially ethnic culture, in GIAHS sites should be given more attention and it is necessary to point out a connection between the conservation of cultural heritage (both tangible and intangible) and agri-cultural heritage.

Because of political sensitivities, many poor ethnic-minority areas in China were not fully open to visitors until 1994 [

26]. In these areas, tourism may also be employed for purposes of social and political control by regimes intent on asserting “one central culture and its values” or accommodating “peripheral cultures with a dominant core” [

21,

27]. In addition, ethnical culture can be over-commercialized during tourism development when they are treated as commodities to be bought and sold (

Figure 5). Therefore, the authentic is replaced by the contrived and artificial and host cultures, and ethnic cultural experiences are ultimately devalued.

These problems not only exist in cultural heritage sites, but also in agri-cultural heritage GIAHS sites, which include rich farming culture, cultural beliefs and traditional lifestyles. As mentioned before, many of the agricultural heritage sites used to be economically backward and ethnic-minority areas. Tourism aims to be a force fostering economic development by causing less ecological damage. However, tourism has linked local’s cultural assets to commercial objectives and was dictated by preconceptions of what visitors wanted to see [

28]. Together with the dominating of

Han Chinese culture, the sustainability of ethnic culture is being threatened, which will indeed influence the sustainable development of agri-cultural heritage systems.

The Grand Song of Dong Ethnic Group was inscribed on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural heritage of Humanity in 2009. A popular saying among Dong people is that “Rice nourished the body and songs nourish the soul” [

29]. The songs express life philosophy and production knowledge. Indeed, the growing of rice and passing on culture and knowledge in music are very important for Dong people’s daily life. Traditionally, Grand Songs are performed formally in the drum-tower, the landmark venue for rituals, entertainment and meetings in a Dong village, or more spontaneously in homes or public places. However, nowadays, Grand Songs are performed widely, regardless of location and occasion, mainly to meet the needs of tourists. As many other cultural traditions, the Grand Songs are losing their authentic and sacred meanings.

4.3. Changing of Cultural Identity

Based on the physical site scale in landscape study, identities have been introduced as: national identity, regional identity, urban identity and local identity. Among them, local identity focuses on people who participate in a very narrative scale of area and how people interact with the local environment [

30]. Being designated as a heritage can provide a platform through which identity can be managed, represented, and rebuilt [

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. In such situations, a heritage generates a sense of identity, belonging, and public memories among local residents through the production of heritage sites and goods [

33], which may “help sustain the ongoing production of local identities” [

30].

However, residents are not solely in control of (re)building their new identity [

34]. Their identity also depends on how outsiders and other entities perceive of them. The notion that identity change can be imposed by outside forces and occurs beyond the control of local residents was prevalent in early studies [

35,

36,

37]. These scholars highlighted how outsiders brought western ideology, values, and markets to the underdeveloped world, leading to commodification and/or impoverishment of local history and cultures [

38].

Since they were isolated from the outside for quite a long time, unity and coherence among the agri-cultural heritage sites has been a key factor regarding collective living and development [

39]. Through communications with each other, people’s emotions become a more common emotion and a more unified identity gradually evolves. Being designated as GIAHS or China-NIAHS sites has put the destinations in front of the world, which has brought significant social, economic, and environmental transformations to the local community. Tourists, investors, researchers and people from all around the world convey modernization, new ideas and fast development to the places. However, the “developmental” factors may give rise to identity change. Such a context renders new insight to the mechanisms by which agri-cultural heritage systems may alter residents’ identity.

Rural areas tend to have a longer memory than cities, due to their more extensive historical and cultural linkages. Chinese culture has traditionally been agriculture-based. Without rural culture, we lose our grounding, history, and diversity. These things not only foster artistic wellbeing, but also intellectual and political independence. Perhaps the central government might neglect the debilitating effect this centralization has on their culture. Protecting and restoring the culture of agri-cultural heritage systems can bring residents a sense of pride and identity, and in turn promote creativity and growth.

Therefore, culture of the GIAHS systems should not only be considered as tourism assets or additional products/information of the agri-cultural heritage systems. While preserving the agricultural heritage systems, the traditional culture should also be cherished and protected as an important part of the system. In addition, culture is closely related to the forming of rural identity of the residents at the agricultural heritage systems. If we say the agricultural system, landscapes, and the ecological system are the body of the agricultural heritage system, the culture, knowledge and rural identity are the soul. However, under the pressure of tourism development and globalization, the conservation of the unique culture and identity of many GIAHS systems are being threatened. Thus, it is necessary to advise the GIAHS experts and scholars to pay more attention on the culture aspect of the GIAHS systems, rather than only focus on the agricultural aspect.

5. Conclusions

In each section, we describe the current situations of GIAHS in Japan, Korea, and China. China has the longest history and engagement with the program, lasting over twelve years, since 2005. Japan has half of the history of China’s connection, going back six years, since 2011, while Korea has the most recent connection, covering the three years, since 2014. Although these three East Asian nations have a common base of agriculture with an underlying reliance on rice farming, each country is aware of their different stages and of their own cultural concerns around agriculture today. Here, we find some common cultural problems and prospects through their systems of management (

Table 2).

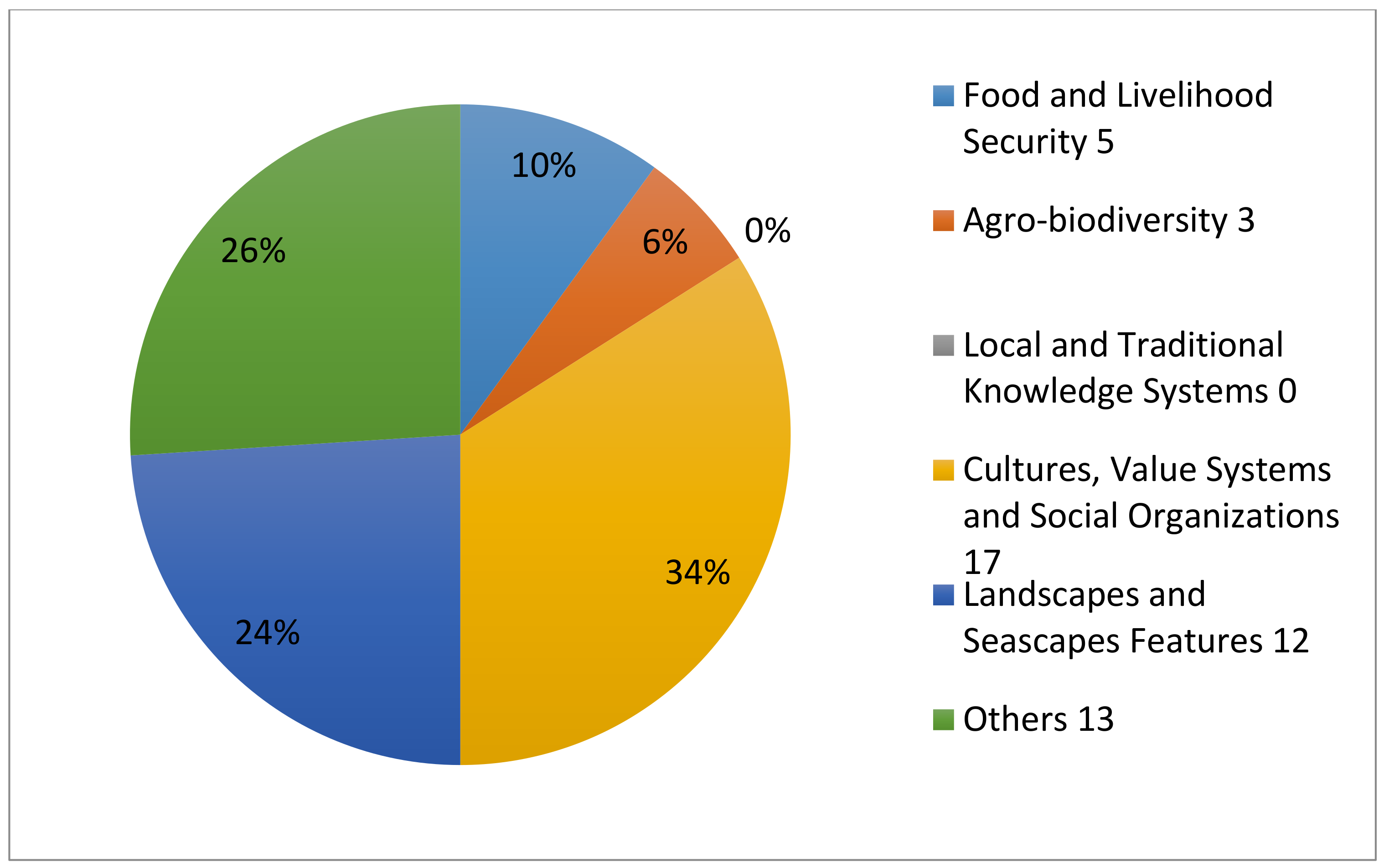

In this paper, we focus upon one of the more neglected criterion of GIAHS, “Cultures, Value Systems and Social Organizations”, among the five criteria. At the same time, we use for our discussions the more clearly defined classification of cultural expressions that are brought by the UNESCO ICH program. However, GIAHS also has to build their own definition and this should be the first task in this field. The case studies in this paper also show GIAHS must more clearly outline the role of culture in this context. Thus far, we show only the examples of Japan, as seen in

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, but how about Korea or China? They also may experiment with similar research and methods for an opportunity to compare results. Moreover, the data, methods used, or analytic techniques we take should be examined more. For example, the data indicated in

Figure 2 and

Figure 3 are gathered from Instagram; however this social media platform is not accessible in China now, where instead they rely upon applications such as Weibo or MeituXiuXiu. The discussion around which analytic methods would be more useful to compare among Asian countries is clearly needed; in particular can comparative data be assessed where there is no common social media platform?

Table 1 is the first attempt to combine the list of GIAHS sites and Japanese Cultural Properties together with the forms of cultural heritage we can see in the GIAHS sites. However, it does not mean that all cultural properties are in turn associated directly with the agricultural heritage systems; they are now just sited in the same locations. Although each Japanese GIAHS site has compiled their own lists, this is as far as research has thus far evolved. There is a need to discuss why and how cultural properties are linked to the agricultural system. Moreover, of course, not only in Japan but in China and Korea there is a need to consider lists comparatively, and analyze which cultural aspects should still be included and which ones omitted from the GIAHS system.

To show the relationship between cultural properties and agricultural systems, this paper suggested the concept of “Agrostory” as introduced in

Section 2.2. On this viewpoint, Korea has much progressed and is now planning GIAHS tourism eagerly, for example as demonstrated in the

Gil Exhibition mentioned in

Section 3.3, which has informed visitors about the relationship between cultural properties and the agricultural system. Hence, many Koreans can understand gradually the importance to conserve their agricultural heritage systems and, on the other hand, many farmers are also recognizing gradually the meaning of utilizing world titles such as FAO GIAHS or UNESCO Global Geoparks.

Such world titles were the honorable results for the local people at first; however, if they mistake the means for the end, it will take on new problems as indicated in the section concerning Chinese GIAHS. Being a site of world designations and changing their original forms or meanings to perform for visitors sometimes brings about identity changes, altering their essential aspects and de-contextualizing their meanings. A similar issue will reliably happen even in Korea or Japan soon. Some cultural anthropologists and folklorists have already pointed out this issue and termed it folklorismus or folklorization [

40], where people begin to utilize their traditional ethnic/folkloric culture but in different and removed contexts to the original. The grouping in this paper also shares the concerns of scientific or disciplinary abuses. For instance, if you always force agriculture to explain every culture, it might fall into the category of Environmental Determinism that cultural geographers had argued against for a long time [

41]. If you set up any cultural steps of development or superiority and inferiority of culture, of course, it also falls into the old-fashioned familiar term of “Social Evolutionism” [

42]. Cultural Anthropologists fought against such attitude or consideration and finally established the concept of Cultural Relativism [

43]. However, now, the behavior of selecting a specific culture from many other cultures as a designated heritage means to discover superiority or inferiority of culture again.

For such new issues emerging out of the processes of globalization, we should set up a common platform to discuss each other’s experiences. Such a platform would have two principle roles: one is for the discussion of positive matters, the other is for the negative ones. In the negative discussion, we have to solve the issues as our common matters that we will face now and the future. Although we already discussed some issues of identity or commercialism above, we still have many other issues. For example, some might criticize the idea of an Agrostory for stuffing cultural diversity into only one story. For such criticism, arguments pointing to the construction of a Geonarrative, instead of a Geostory, among the Geopark networks will be a useful experience to draw from [

15].

In the positive discussion, we can deal with the differences or similarity through comparative studies. Whether the traditional cuisine can be a cultural property, for example, is an interesting cultural issue. In China, we can find abundant Chinese foods and cooking ways are designated as the ICH of China, however, there are currently only a few in Korea with the designation of special palace cuisine or brewing traditional alcohol, and no examples in Japan. On the other hand, Korea and Japan have UNESCO ICH of food (Both of ‘Kimjang, making and sharing kimchi in the Republic of Korea’ and ‘Washoku, traditional dietary cultures of the Japanese, notably for the celebration of New Year’ were designated as ICH in 2013 by UNESCO) but China does not at all. The discussion about these matters in GIAHS can give some effective suggestions to the discussions on UNESCO in turn. China, Japan and Korea have a lot of common culture such as tea planting or women divers, as introduced in

Section 2.1 and

Section 3.1. Some members are already searching for a way to cooperate transnationally with their common agricultural products (for instance, Shizuoka GIAHS held an international forum of tea in May of 2016 and also invited people concerned with Chinese and Korean GIAHS of tea). Tea is one of them and we surely can make comparative research on sites that have tea industries such as Fujian GIAHS of Jasmine oolong tea in China, Shizuoka GIAHS of green tea in Japan, or Hadong GIAHS of green tea of Korea. Women divers are also common cultural features of both Korea and Japan, and UNESCO ICH in Jeju GIAHS, also an important cultural property in Noto GIAHS in Japan. In this paper, we point out our eight common cultural problems and prospects, the discussions of such specific cultural theme in each GIAHS will need to be deepened further from now.