1. Introduction

In the past decade, China saw many scandals related to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), such as food safety problems (e.g., Sanlu milk powder, Sudan red, dyeing of steamed bread, poisoned bean sprouts, and so on), oppressive labor (e.g., Foxconn successive jumping), and industrial pollution (for example, see [

1]). It seems that CSR status in China is not optimistic. However, it should be optimistically noted that many enterprises are active and generous in disaster rescue and donation, providing their best to society. A question that might come into one’s mind is whether or not the Chinese government intervenes in CSR, and how the government regulates CSR in an imperfect market economy.

CSR may be understood as the responsibility of enterprises to protect the interests of stakeholders, including consumers, employees, suppliers, and communities. Davis (1960) advocates the “iron law of responsibility” about CSR [

2]. Enterprises should fulfill the corresponding social obligations when they are given access to social resources and rights. In the process of planning and decision making, enterprises should take into account factors that affect society in addition to their own interests. Davis and Blomstrom (1975) further point out that CSR is the responsibility to protect and improve the public interest when enterprises pursue their own interests [

3].

Aguilera et al. (2007, p. 837) put forth an important question “what catalyzes organizations to engage in increasingly robust CSR initiatives?” [

4]. It is argued that CSR “(a) allows for discovery of new business opportunities in response to new societal trends; (b) provides ‘halo’ effects on a company’s reputation that enhances marketing and hiring efforts by the company, and (c) limits downside risks associated with violating societal norms” (see [

5] p. 5). Enterprises involved in CSR respond instrumentally to external demands or to maximize certain interest in profits [

6]. CSR helps maintain enterprises’ own reputations, and long-term CSR investment is needed to establish a socially responsible reputation [

7].

Enterprises’ CSR and government policy development are interactive. As the main market regulator, the government bears the responsibility of supervising the market order according to the law to maintain fair competition environment. Through the establishment of regulations and laws to regulate and adjust the behaviors of enterprises, the government plays a directing role in promoting the implementation of CSR.

A prior study which focused on European public policies on CSR suggested five policy instruments (legal, economic, informational, partnering, and hybrid) that are useful to shape and promote CSR in various fields of action [

8]. Similarly, Škare and Golja (2014, p. 562) found that “

CSR firms positively affect economic growth and that countries that strongly support CSR achieve higher growth rates” [

9]. Del Baldo (2017) provided an overview of the process and the models related to CSR diffusion based on a public–private involvement perspective [

10]. In general, insights about the factors determining CSR development are still rare, particularly in emerging economy contexts [

11].

In particular, with China being a major emerging economy, the Chinese government is the major owner of the state-owned enterprises [

11], which constitute the main body of China’s economy [

12]. Incorporating cultural contexts could contribute to studies on China’s CSR [

13]. CSR formulation and implementation in China differs from its ‘western’ progenitors, and Chinese history and institutions are critical in fashioning an alternative model and practice, in which the state and private corporations form active partnership and collaboration [

14]. Accordingly, Jamali et al. (2017) drew from an institutional logics approach to present the CSR logics in developing countries of China, India, Nigeria and Lebanon [

15]; Hofman et al. (2017) argued that CSR development in China is state-led society-driven [

16].

The development of CSR in China has a short history of about a decade. Differently to western countries’ emphasis on corporate consciousness of philanthropic responsibility, CSR development in China has been guided by the government as a social legitimacy rebuilding lever since 2006 [

5,

17,

18]. Then, Chinese enterprises set off a learning process on CSR initiatives, which is evident from the rapid increase in the number of Chinese enterprises issuing CSR reports [

17].

In order to facilitate the development of CSR, guidelines for CSR have been established by various parties in China. While the Shenzhen Stock Exchange issued guidelines on CSR in 2006, China Consumer Association issued “guidelines on CSR to protect consumers’ interests” on 15 March 2007. As the new “Labor Contract Law” was implemented on 1 January 2008, enterprises are required to fulfill CSR in labor and employment in accordance with the new regulations. Yet, how to encourage enterprises to fulfill CSR remains a challenge for both the government and society. This is mainly due to the defects of market mechanisms in China, where enterprises usually lack self-initiatives in CSR. Thus, it usually relies on the government to drive the CSR of enterprises. The traditional leading role of Chinese government makes CSR development in China a “top-down” approach, where provincial governments diligently promote adoption of CSR and gradually introduce a series of CSR standards to enable assessment of enterprises’ CSR performance.

China has its hierarchical system of bureaucracy with fragmented administration authorities and sectors related to the umbrella CSR affair in developing markets. The complicated government structures and organizations make the ways in which the government plays its role in directing CSR development rather curious. Many articles have tried to capture a clue or identify a relationship from a specific perspective but failed to present an overall evolutionary image of the governments’ role.

Political embeddedness is a typical perspective to explain the relationship of corporate compliance with governmental expectation of CSR. Enterprises become important participants and contributors to achieve the government’s mission by following government guidelines as an effort to shape its political legitimacy [

19,

20], which reflects “

the extent to which the government views the firm’s actions as being in accordance with norms and laws” (see [

21] p. 127). Realization of such efforts of enterprises requires attaining desirable resources from the government [

22,

23,

24], and those resources are especially significant in emerging economies where enterprises tend to depend more on informal mechanisms due to limited support from formal organizations [

21,

25,

26]. Accordingly, political dependence and government monitoring are two key factors in shaping enterprises’ CSR in emerging economies [

21]. The key features of enterprises’ political embeddedness determine their dependence on and complementarities with government policies [

24,

27,

28].

Prior studies suggested that factors such as enterprises’ features, shareholding ration amongst internal management, governance structure, and external stakeholders, are important factors in influencing enterprises in fulfilling their CSR [

11,

29,

30]. Prior research also indicate that different governments apply different approaches in driving enterprises to fulfill their CSR standard due to differences in corporate and management culture in different countries. For example, the European governments often use the means of public policy to guide enterprises to fulfill their CSR, in comparison to the US government [

31]. European enterprises tend to have trust in the government and agree with the public policy of CSR, as they believe that government policies help them identify the direction of global economy development. While CSR largely relies on self-regulation by enterprises, the government plays an important role in guiding corporations to fulfill CSR by providing a national governance system [

32]. Also, the institutional differences between developed and developing countries often result in a different level of CSR [

33]. Attig (2016) finds that an enterprise’s degree of internationalization correlates positively with CSR performance, and the overseas subsidiaries in countries with a good political and legal system have better CSR performance [

34]. In line with this finding, prior studies suggest that government policy and regulation is a key driver of CSR. Managers often take government policy as guidance, and assume the government provides a clear and fair-competition environment for enterprises to effectively achieve their objectives. Enterprises follow government guidelines and enhance brand image and reputation by fulfilling CSR, so as to avoid more stringent control from government [

35].

Regulations, policy, standard setting, and government promotion actions of CSR can significantly affect corporate responsible business activities and strengthen the compliance with regulations [

36,

37]. Like many other governments in the world, Chinese governments at various levels have introduced many measures over the past decade to encourage CSR as a clear policy objective. At the same time, interdisciplinary research on CSR booms around the world. There are more and more studies on emerging markets like China. However, the role of the government in these studies has not been carefully verified so far, especially in China’s institutional and cultural background. Relationships between government and enterprises are more subtle and complicated in China than in other countries [

38]. The role of the Chinese government in guiding CSR needs to be studied. But as yet, no one has empirically presented the overall evolution of the ways in which the Chinese government deploys its guiding strategy on CSR.

This paper is to fill this gap by analyzing policy documents issued by the Chinese government based on metagovernance theory. The focus of this paper is to unearth the guiding role of Chinese government policies on CSR development in China. There is already literature that provides a review of Chinese CSR. In order to avoid distracting from the central focus and avoid repetitive work, we did not write a long literature review of the vast literature system on CSR. We limit the references to a few sources related to the central topic of this paper on CSR to make the writing smooth and cohesive. This paper uses quantitative text analysis to investigate the research question: How does the Chinese government use policies to guide the enterprises to fulfill CSR? By answering this research question, this paper innovatively uses metagovernance theory to explain the guiding role of the Chinese government on CSR development, and empirically answers the central question of metagovernance about the ways in which the organization of metagovernance is carried out [

39] by illustrating the networked effect of China’s CSR policy, contributing to advances in understanding of the relations between government policy and CSR development.

2. Theoretical Basis

Metagovernance can be defined as a coordinated governance paradigm via designing and managing sound combinations of hierarchical, market, and network governance, to attain the best possible achievements from the perspective of those responsible for public affairs [

40]. Metagovernance is “

a way of enhancing coordinated governance in a fragmented political system based on a high degree of autonomy for a plurality of self-governing networks and institutions” (see [

39] p. 100). So, metagovernance can be understood as “

the organization of self-organization” (see [

41] p. 42). It requires the capacity to structure various governance sectors and link dispersed regulatory resources and actors [

42] by increased communication among participants in the formulation and implementation of government policies [

43]. The basic conditions of metagovernance theory—such as hierarchical, market, network, coordination, fragmented governance system, and self-governing— make the metagovernance theory quite suitable to be laid as the foundation to explain the relationship between government policy and CSR development. CSR activity can be seen as self-governing behavior, which takes place in a market environment supervised and coordinated by a hierarchical networked fragmented governance system. This situation is in line with China’s contexts.

Metagovernance theory confirms that the government is responsible for coordination [

44]. For social governance structure, metagovernance theory implies that the government is not only an authoritative organization, but more importantly is to guide the progress of the development of society; establish guidelines for social functioning; and be responsible for the vision, planning, design, and formulation of institutional system and policies [

39].

The central question for many governance theorists is how the organization of metagovernance is carried out [

39]. There is a so called “hands-off” way through the shaping of the political, financial, and organizational context within which self-governance takes place while the metagovernor is not in direct contact with the self-governing actors [

39]; the opposite is a so called “hands-on” way through offering support and facilitation to self-governing actors [

39,

41,

45]. The guidance of the Chinese government towards CSR development fairly exhibits the two ways. The government does not directly interfere in corporate operation but, through shaping the political, financial, and organizational context by government policy, promotes self-governing behavior (e.g., CSR) of enterprises. The government also rewards enterprises that engage in CSR initiatives by offering support and facilitation to self-governing actors (enterprises). The “hands-off” and “hand-on” ways form a coordinated effort. The evolution process of CSR is not haphazard but guided by meta-governance principles which are deliberated by government and enterprise in an interactive learning context [

46].

3. Materials and Methods

“Textual data are arguably the most widely available source of evidence on political processes; political documents have a great potential to reveal information about the policy positions; content analysis was developed to make systematic use of this rich data source” (see [

47] p. 536). Quantitative text analysis is a kind of semantic analysis technique using both quantitative and qualitative methods. Through content analysis and text mining on open-access policy documents, the patterns of policy evolution and intention can be discovered. Quantitative text analysis enables identification of contextual conditions and development trends of policy, uncovering the underlying characteristics and implicit principles.

Policy documents provide us with evidence that reflects the evolution of a government’s governing philosophy. In the previous studies on policy evolution, qualitative analysis is commonly employed to delineate dynamic changes of policy documents. Yet, such an approach to analysis is inherently subjective. This paper uses quantified method to analyze policy documents related to CSR that allows us to visualize changes in policy themes and their characteristics, and governing philosophy, by presenting the patterns of changes.

The keywords analyzed by co-word analysis can reveal interactions among policy documents. Accordingly, the co-word, frequency, and clustering analysis of policy keywords in different phrases are utilized in mapping policy topics and tracing policy pattern in development. This approach incorporates quantitative techniques with qualitative data, reducing the problem of subjectivity.

Co-word analysis identifies relationships between keywords by recording their co-occurrence in policy documents [

48]. It is a technique of content analysis for analyzing the strength of association between themes and ideas in textual data [

49]. Clustering analysis is used to measure the strength of relationships among keywords according to the criteria of maximizing the difference between groups and minimizing differences within the group. In this study, the extracted keyword types are industry types, policy document types, important verbs, responsibility types, policy subject words, and governmental sector names in each policy document. Cluster analysis is applied to visualize the co-word clusters [

50], so as to show in the cluster level which governmental sectors enact relevant policy documents, which industries draw attention from the government, and what are the main concerns of the government about CSR.

The CSR related policy documents in 2005–2013 were collected to be the sample for this study for a number of reasons. In 2006, the Shenzhen Stock Exchange issued “guidelines on CSR”, which is seen as the first official policy document from the government for guiding CSR. The publication of this guideline was attributable to the initiation and preparation by the government one year ahead. Thus, the policy documents published in one previous year (i.e., 2005) can also be included as a sample to allow the examination of the policy evolution with data that reflects a full process of development from the initiation stage. The use of government documents related to CSR is appropriate to examine the variability and variety of the governing landscape, internalizing policy subject, object, goal, and instrument. Exploring CSR documents is appropriate to better understand research propositions of policy science. For this study, the source materials include a total of 436 CSR related policy documents from the Chinese government. Since government cannot enforce direct intervention on CSR behaviors, we notice through content analysis and textual comprehension that some notions like “monitor” or “measure” or “enforce” in government policy documents are usually used for special regulation on certain tasks or illegal behaviors but not for guiding CSR; therefore, these words are not taken into account in this study. In addition, only the policy documents that explicitly contain the exact words of CSR are collected for analysis because the indirectly related policy documents are vast and contain a lot of irrelevant information that can bring interference into the analysis. So, some agencies and some documents (e.g., those related to water sustainability [

51], like the Ministries of Water Resources, of Agriculture, and the State Oceanic Administration etc.), although they may indirectly relate to CSR, are not included in this study.

China is a typical emerging economy with CSR being shaped by corporate political dependence and government monitoring [

21,

52]; however, few insights on the factors which determine CSR level and its enhancement in China have been offered by the previous literature [

11]. This paper may contribute to filling this gap, and provide evidential and empirical insights. Co-word analysis, cluster analysis, and network analysis are applied to outline the evolution of governmental policy guidance and the participation of different governmental sectors and industries. Accordingly, the three aspects that we focus are: evolution of industry involvement in metagovernance of CSR, evolution of intergovernmental relations in CSR policy formulation, and evolution of policy relations on guiding CSR. The State Grid corporation of China is adopted as a sample frame to identify how macroeconomic policies influence microeconomic self-governing actor’ CSR evolution in terms of time frame, evolution stage, and focus of attention. By doing so, we investigate the role of government in guiding enterprises to fulfill CSR, providing metagovernance explanation of the guiding role; and empirically answer the central question of metagovernance about the ways in which the organization of metagovernance is carried out via illustrating the networked effect of the government policy, contributing to a deeper understanding of the relation between CSR development and government policy intention.

4. Results

4.1. Evolution of Industry Involvement in Metagovernance on CSR

The Chinese government issued a number of policies related to labor rights, environment protection, health and safety, and consumer rights etc. to regulate corporate practices. The policies use both voluntary and compulsory tools, enabling CSR implementation moving forward in China.

The government’s metagovernance ideas change with the continuous development of politics, economy, and society. Government policy documents are the footprints of the government in performing its functions, serving as the ‘mirror’ reflecting the metagovernance ideas of the government. Policy objectives and policy themes are internalized in the policy documents, and change with the government’s metagovernance ideas. In the past, the research on policy evolution was mostly based on qualitative policy literature interpretation, so it was difficult to avoid the subjectivity of the researchers. Quantitative text analysis on policy documents can describe the evolution of industry involvement in metagovernance of CSR. The evolution can be quantitatively and visually depicted, showing the policy attentions, and avoiding the defect of subjectivity in analyzing policy documents.

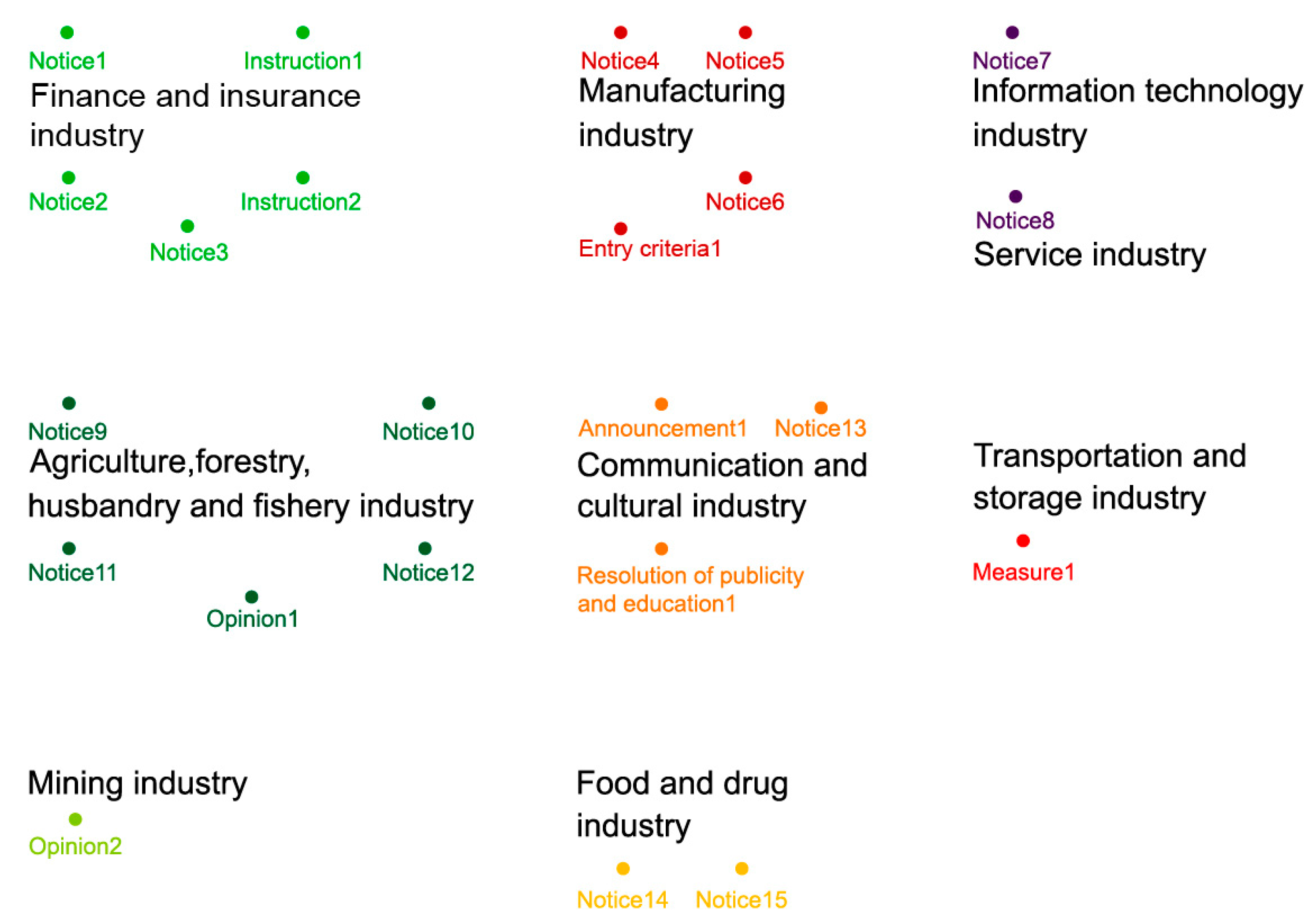

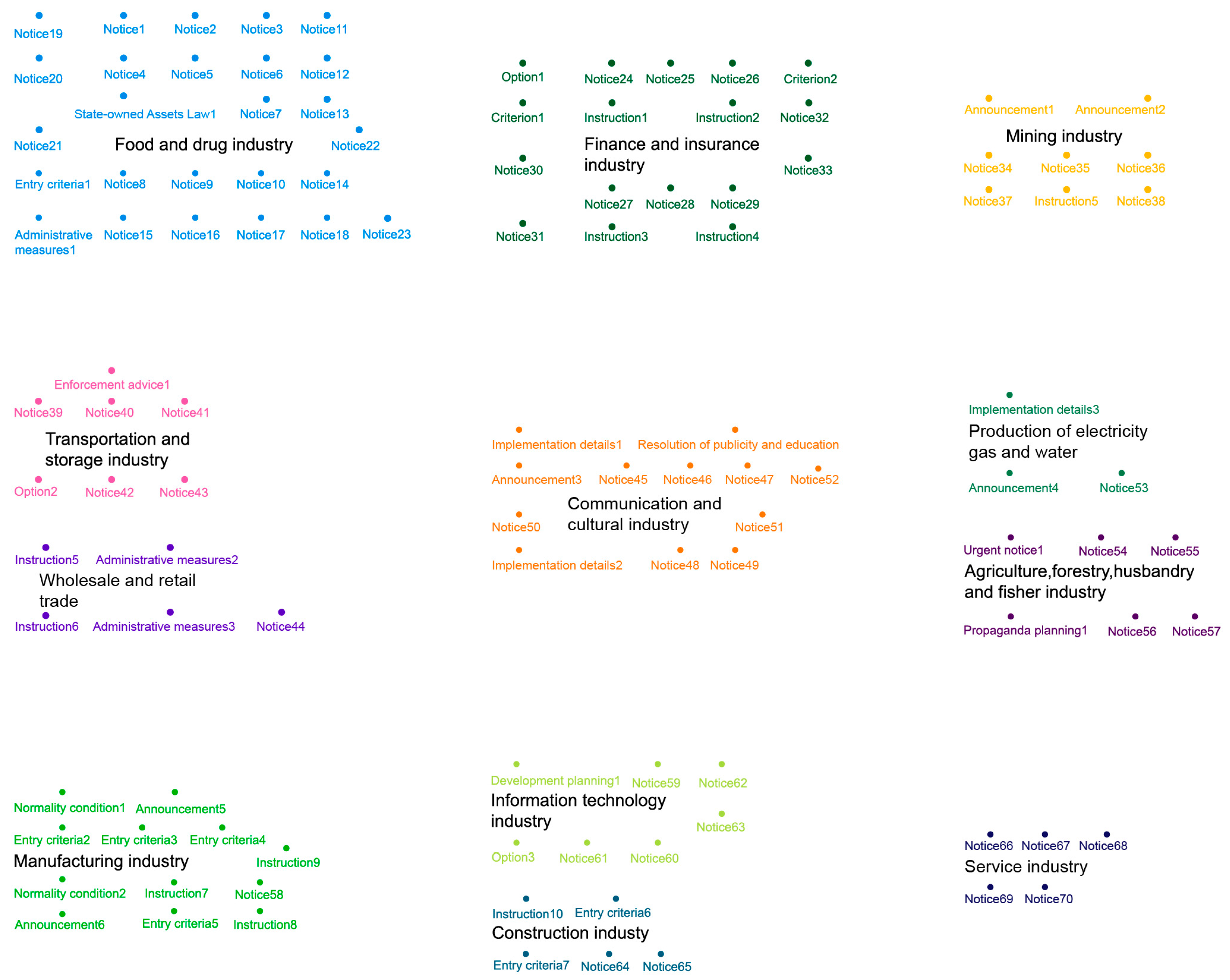

To see the evolution of industry involvement in metagovernance of CSR, we grouped the documents into a 3-year span. Policy documents are grouped, as per, into three consecutive sub-periods: 2005–2007, 2008–2010 and 2011–2013, respectively, and are depicted in

Figure 1,

Figure 2 and

Figure 3. Three sub-period divisions are appropriate to identify the characteristics in each sub-period, and, at the same time, to avoid small divisions that might result in failing to capture the evolution of the period.

As shown in

Figure 1, in 2005–2007, few CSR policies were developed in that period. The policies in the period were confined to the financial and insurance industry, and the agriculture, forestry, husbandry, and fishery industries. It reflects that the Chinese government paid more attention to economic and agriculture development in that period of time, and the development of metagovernance of CSR was in its early stage.

According to

Figure 2, in 2008–2010, the number of CSR related policy documents grew significantly with newly added industries covered by the CSR policy system. The foci of CSR policies shifted from traditional agriculture, finance, and insurance industries to the manufacturing, food, and drug industries, illustrating the transition of metagovernance emphasis among industries.

As can be seen in

Figure 3, in 2011–2013, the policy counts further increased with more CSR related policies imposed to the communication and cultural industries. With the flourish and popularity of information technology such as the internet, smartphones, and new media, communication and cultural industries achieved rapid progress in this period. Thus, there were more CSR related policy attentions to this field in this stage.

In sum, there was a steady increasing trend in the CSR policy quantity in 2005–2013. More and more industries became involved in the metagovernance of CSR covered by the policy system. The industry types which CSR policies focused on shifted with time, which reflects different industry dominance and policy attention in different sub-periods, visualizing the evolution of industry involvement in metagovernance of CSR.

4.2. Evolution of Intergovernmental Relations on CSR Policy Formulation

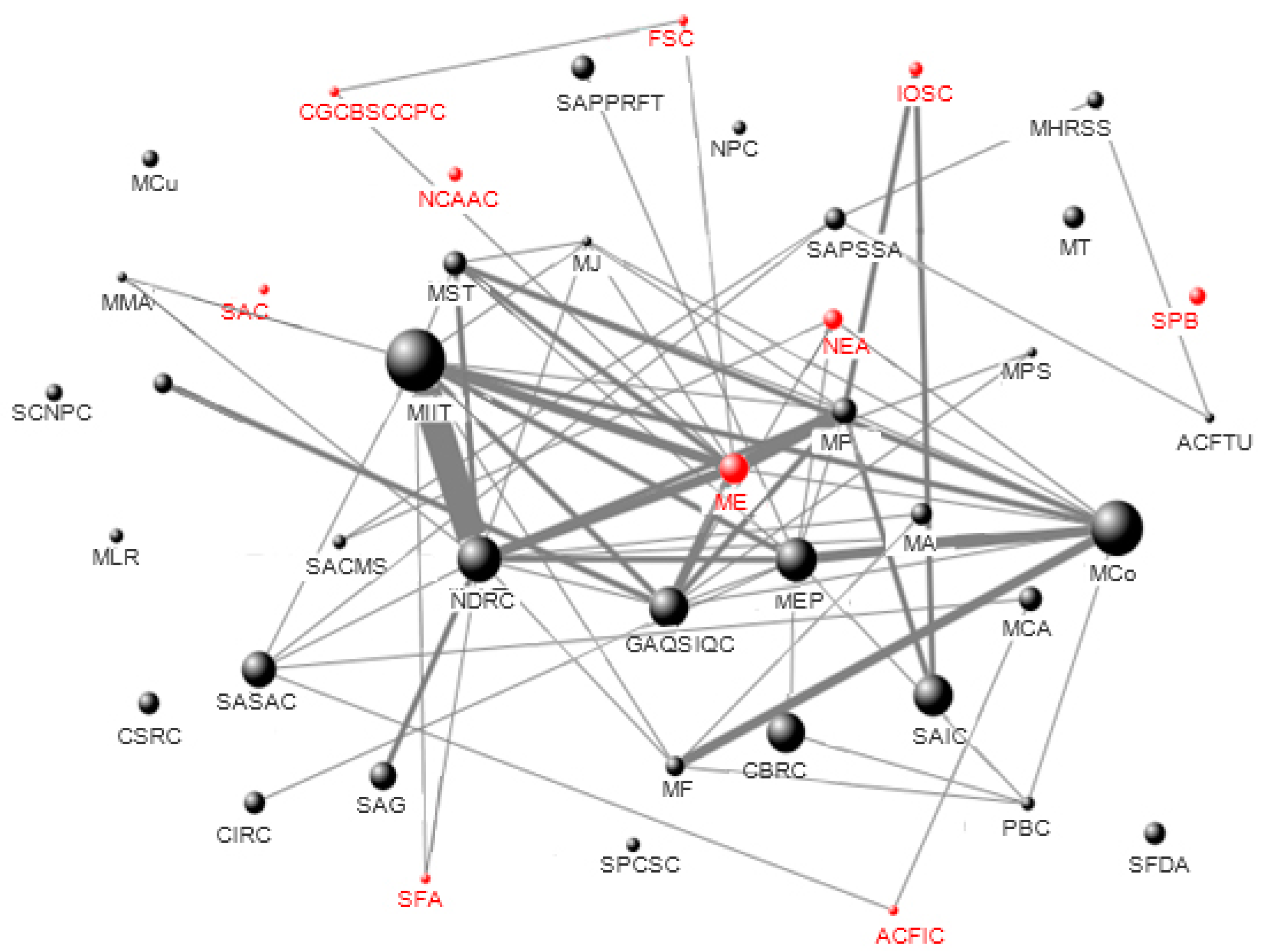

In China, CSR policy formulation and implementation involves collaborative efforts across agencies, including the party, government organisations, and non-governmental organizations such as industry associations. These agencies play important roles (e.g., surveillance, service, and collaboration) in bridging the gap between government policy enforcement and CSR implementation by enterprises. Co-production of policy documents across agencies can be useful for agencies to complement one another’s strengths to establish collaboration, which reflects the style and merit of metagovernance. We identify the co-work network by developing network graphs that visualize collaboration across agencies, helping detect intergovernmental relations and patterns in CSR policy development. By using network analysis, intergovernmental collaborative patterns and relationships are discovered. The network of function division and collaboration between agencies suggests an interrelationship and complexity of public affairs that are supported by intergovernmental relations, illustrating the intergovernmental interactions of metagovernance.

To conduct network analysis, we first identified the government agencies that participate in formulating policies, and considered each participant agency as a node and the collaborative policy document as a link between the participant agencies. The list of government agencies is denoted in

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. The thickness of the link between two nodes represents the co-production frequency between two agencies, and the size of a node represents the number of policies involved with this agency. In view of the importance of environmental and social development, increasing numbers of government agencies are involved in the CSR policies formulation process, revealing the flourish of metagovernance for CSR affairs. The collaborative networks of the three periods are shown in

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, in which the red nodes denote the newly added government agencies in the current period compared with the previous one.

The abbreviations in

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 are listed as follows:

| SIPO: | State Intellectual Property Office |

| NHFPC: | National Health and Family Planning Commission |

| CEC: | China Enterprise Confederation |

| MHURD: | Ministry of Housing and Urban Rural Development |

| PAOSC: | Poverty Alleviation Office of the State Council |

| ACWF: | All-China Women’s Federation |

| FSC: | Food Safety Committee |

| CGCBSCCPC: | Central Guidance Commission for Building Spiritual Civilization of the Communist Party of China |

| IOSC: | Information Office of the State Council |

| NCAAC: | National Certification and Accreditation Administration Committee |

| SAC: | Standardization Administration of China |

| NEA: | National Energy Administration |

| SPB: | State Post Bureau |

| ME: | Ministry of Education |

| SFA: | State Forestry Administration |

| ACFIC: | All-China Federation of Industry & Commerce |

| CSRC: | China Securities Regulatory Commission |

| MT: | Ministry of Transportation |

| MJ: | Ministry of Justice |

| SAIC: | State Administration for Industry and Commerce |

| SCNPC: | Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress |

| MEP: | Ministry of Environmental Protection |

| FM: | Finance Ministry |

| MST: | Ministry of Science and Technology |

| NDRC: | National Development and Reform Commission |

| MP: | Ministry of Propaganda |

| MA: | Ministry of Agriculture; |

| MCo: | Ministry of Commerce |

| EPB: | Environmental Protection Bureau |

| CBRC: | China Banking Regulatory Commission |

| MH: | Ministry of Health |

| GAQSIQC: | General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of China |

| SAPSSA: | State Administration of Production Safety Supervision and Administration |

| SCET: | State Commission for Economics and Trade |

| MPS: | Ministry of Public Security |

| PBC: | People’s Bank of China |

| DLSS: | Department of Labor and Social Security |

| NPC: | National People’s Congress |

| MCA: | Ministry of Civil Affairs |

| ACFTU: | All-China Federation of Trade Unions |

| SFDA: | State Food and Drug Administration |

| SASAC: | State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission |

| SPCSC: | Safety Production Committee of the State Council |

| MHRSS: | Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security |

| SAPPRFT: | State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television |

| MCu: | Ministry of Culture |

| CCGPC: | China Central Government Procurement Center |

In 2005–2007, as shown in

Figure 4, the links between the nodes are narrow and restricted, revealing relatively infrequent interactions amongst agencies for making CSR policies, implying China’s metagovernance on CSR is in its initial stage.

As shown in

Figure 5, in 2008–2010, the number of government agencies involved in CSR policy increased. Each agency produced more CSR policy documents, and cross-agent collaboration became more frequent. The National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Commerce, General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of China, State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission, and Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, were the most productive agencies in producing CSR policy. The collaborations among five agencies, namely National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Commerce, General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of China, and Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, were strengthened in the period. This indicates that co-production CSR policies became prevalent, implying China’s metagovernance of CSR was improving and developing towards a new stage.

As

Figure 6 shows, in 2011–2013, the number of government agencies and their collaboration further increased. National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Commerce, General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of China, State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission, and Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, were particularly productive in this period. Government agencies concerned with CSR collaborated extensively, implying that Chinese government agencies had an active role in guiding CSR and that China’s metagovernance of CSR is extensively developed.

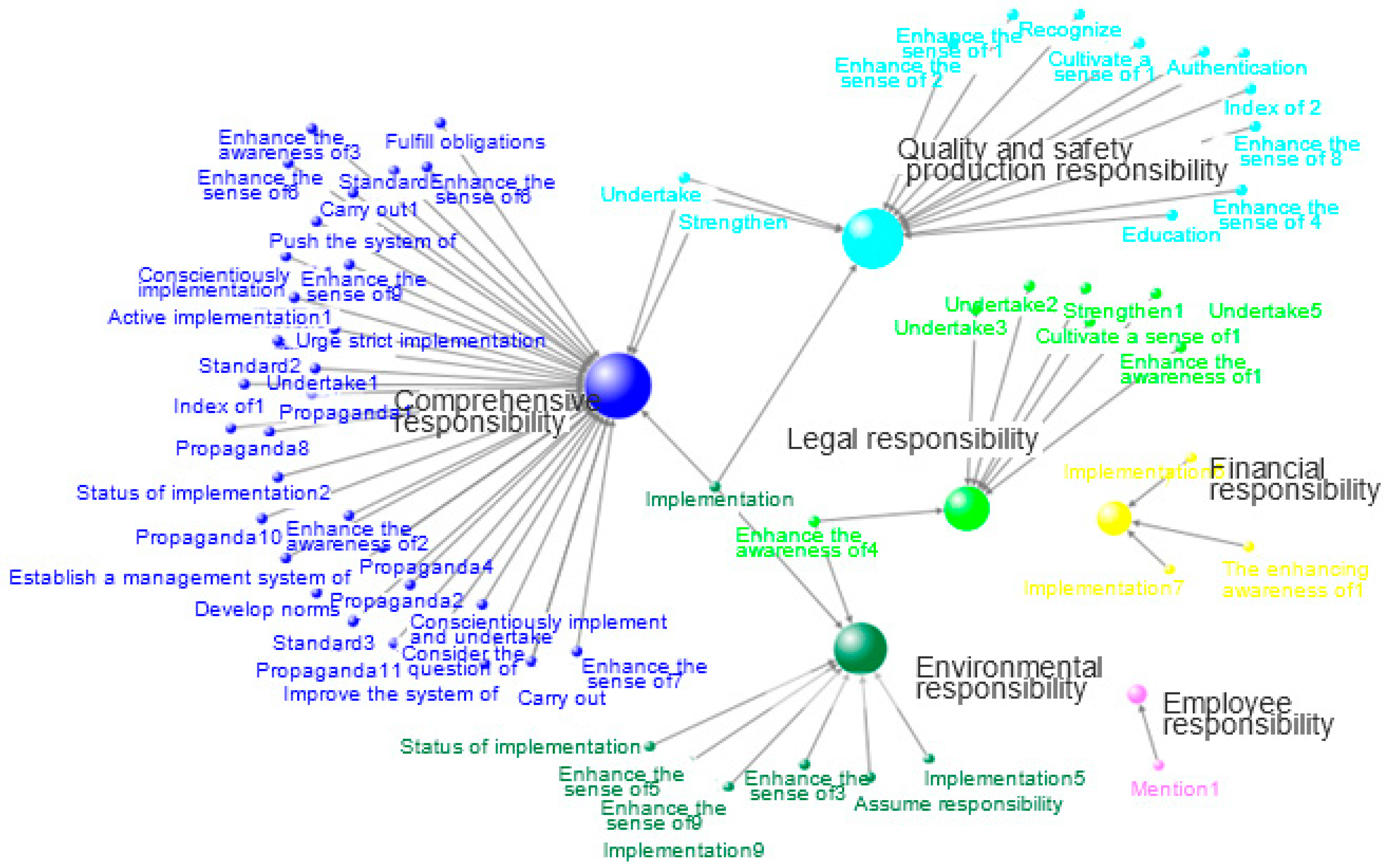

4.3. Evolution of Policy Relations on Guiding CSR

Quantitative text analysis was used to analyze reference relations and further discover the inheritance, progress, and development of policy intention. Citation and reference of policy documents provide empirical evidence that implies policy intention diffusion and value delivery.

Policy relations, which indicate metagovernance implementation structure, manifest in either title or text body. Overt relations are presented in literal descriptions of policy contents and identified through similar policy intentions. After a period of time, policy relationships could be constructed by networking relationships with data to map policy network characteristics. Policy relationships and network structure can reflect policy entanglement, derivation, and affiliation, revealing the implementation structure of metagovernance. Some latent relationship can also be discovered.

There are cues and terms—such as performing, undertaking, encouraging, raising consciousness, promoting, etc.—for identifying policy inheritance and association (Huang et al., 2015a). Text analysis of policy documents showed that government policies had offered guidance for specific areas of CSR such as economic responsibility, legal responsibility, employee responsibility, consumer responsibility, environmental responsibility, quality and safety responsibility, and charitable responsibility.

In different periods, the government emphasizes different strategic targets that guide enterprises to shoulder different responsibilities, as can be seen from the word usage frequencies mined from policy documents. One may see the change in policy intentions by referring to the change of keywords in policy documents.

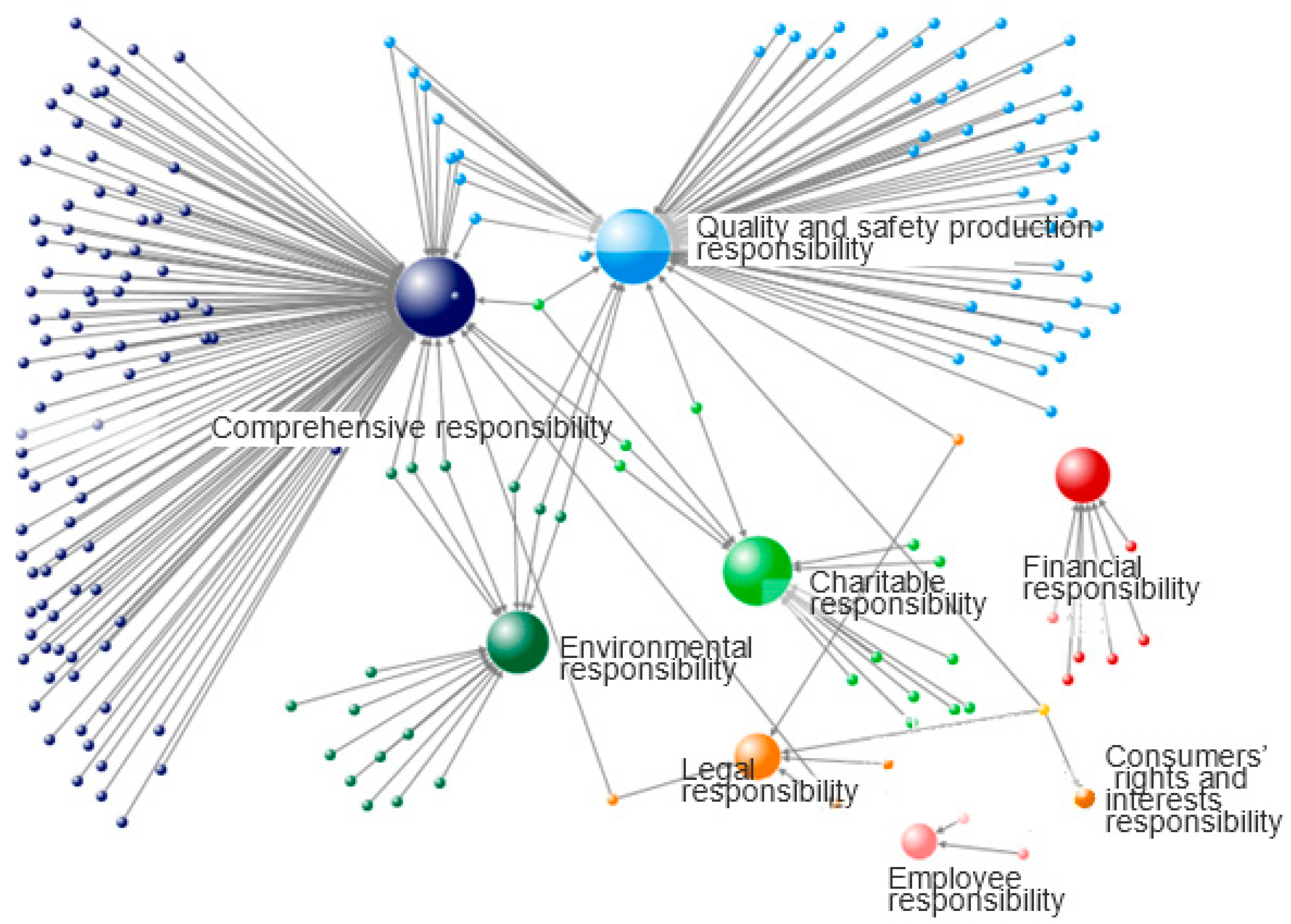

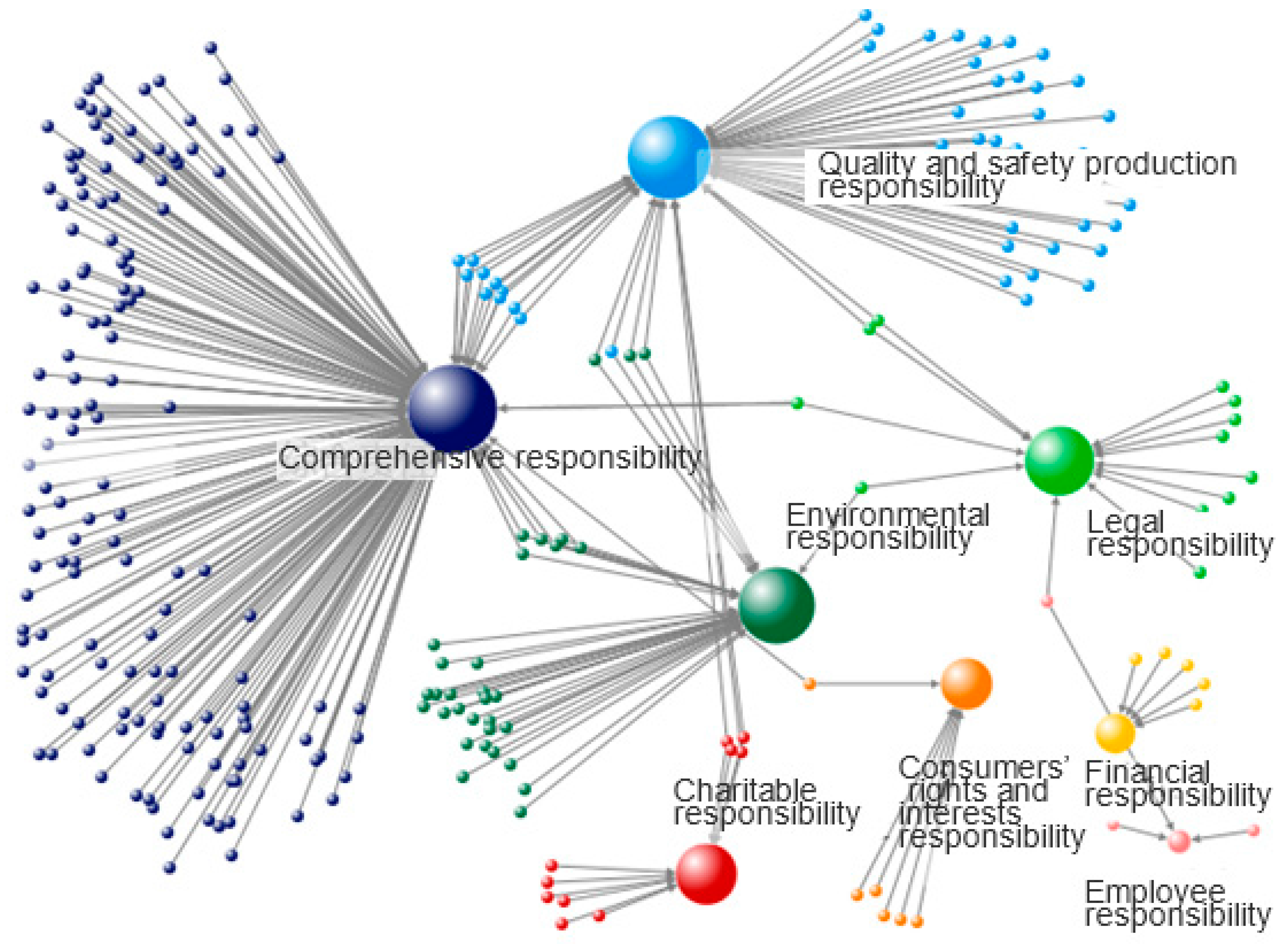

In

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9, the size of the nodes denotes the frequencies of various social responsibilities, such as charity, employees, environment, etc. The branches denote quotations or citations via verbs, which indicate inheriting from or association with other policy documents [

53]. A larger size of node represents more concerns raised about the specific type of social responsibilities in the policy documents. The figures show that the government has shifted the emphases over time to encouraging enterprises to extend their social responsibilities, manifesting metagovernance in operation.

As

Figure 7 shows, in 2005–2007, the Chinese government began to require enterprises to fulfill social responsibilities in several aspects. The verbs used to drive the enterprises to fulfill their social responsibilities include, “enhance the sense of”, “consciously implement”, “strengthen the awareness of”, “cultivate the sense of social responsibility”, and so on (for an example, see

http://www.cbrc.gov.cn/govView_91D73B8D49484BF4B1D87D29F9577C2D.html), implying that the Chinese government is concerned about the social responsibilities of enterprises.

As

Figure 8 shows, in 2008–2010, CSR policies continued to grow and were extended to include charity responsibility and consumer rights. Government agencies are concerned about various social responsibilities of enterprises. The Wenchuan earthquake in 2008 resulted in charity responsibility policies increasing, along with other social responsibilities such as quality of production, safety responsibility, and environmental responsibility, indicating the important role of the Chinese government in promoting CSR. In these policies, the Chinese government also used terminologies, such as “effectively undertake”, “actively implement”, “seriously implement”, and others, urging enterprises to fulfill their CSR.

In 2011–2013, as shown in

Figure 9, emphases were placed on quality and safety production responsibility, implying a series of problems in relevant areas such as the Clenbuterol in pork, the oil spill in Penglai at Shandong province, the Wenzhou train collision, and water pollution from Changzhi city at Shanxi province. Wording emphasis was put on implementation, institutions, and systems expressed in CSR policy documents.

5. Empirical Analysis of the State Grid Corporation

To verify our findings above, we conducted a case investigation to further examine the impact of policy development on CSR development. State Grid Corporation of China is a state-owned enterprise that was approved by the State Council of China for establishment in 2002. Having its core business as construction and operations of power grids, State Grid Corporation’s mission is to provide economic, safe, and reliable electrical services. Having become a mega enterprise, State Grid’s businesses cover 26 provinces in China. The population of users amounts to more than 1.1 billion. State Grid also extends its business in other countries, such as Philippines, Brazil, Portugal, and Australia. State Grid ranked No. 2 in the world’s top fortune 500 firms in 2016 and is the world’s largest public utility enterprise. State Grid is the first state-owned enterprise in China to release a CSR report. The CSR development of State Grid is at the forefront of China’s state-owned enterprises; thus, State Grid is appropriate for this study as it has typicality and significance to be studied as the representative enterprise in fulfilling CSR.

The CSR report issued by State Grid explains the concept of CSR that advocates that CSR is its responsibility to all stakeholders, and the natural environment. CSR is also its premise for sustainable development of enterprise, economy, and society. With reference to the business nature of the enterprise, State Grid discusses various aspects of social responsibility in its CSR report. It points out that it is important to improve the ability of fulfilling CSR for all enterprises. State Grid believes that CSR fulfillment and enterprises’ development are complementary, and enterprises should take socially responsible actions to address public interest, and sustain a society by offering a steady supply of inputs and resources for the survival and development of enterprises.

In 2006, State Grid released its first CSR report for the year 2005. As one of China’s leading enterprises, which can be considered by other enterprises to reflect government intention, the time frame of its first step in CSR disclosure is in accordance with the government initiative. 2005–2007 was an initial stage in which the Chinese government conveyed CSR requirements by official policy documents to promote CSR. Thus, some elementary and general guidance was given to cultivate the sense of social responsibility of Chinese enterprises.

In 2008, as the year of the occurrence of the southern icy rain and snow event, Wenchuan earthquake, and Sanlu milk scandal, which highlighted the importance of enterprises’ charitable responsibility practice in catastrophic events, and responsibility practice for ensuring product quality. Accordingly, the government paid more attention to the implementation and practice of CSR. Therefore, in 2008–2010, more policy documents were introduced about the implementation and practices of CSR.

On 1 November 2010, the International Standard Organization (ISO) held a ceremony in Geneva at Switzerland to formally introduce the standards of social responsibility guidelines (ISO26000). After that, in the following years, the Chinese government paid more attention to the institutionalization and systematization of CSR and released relevant policies to encourage enterprises to develop responsibility institutions and systems to follow the international guidelines of ISO26000

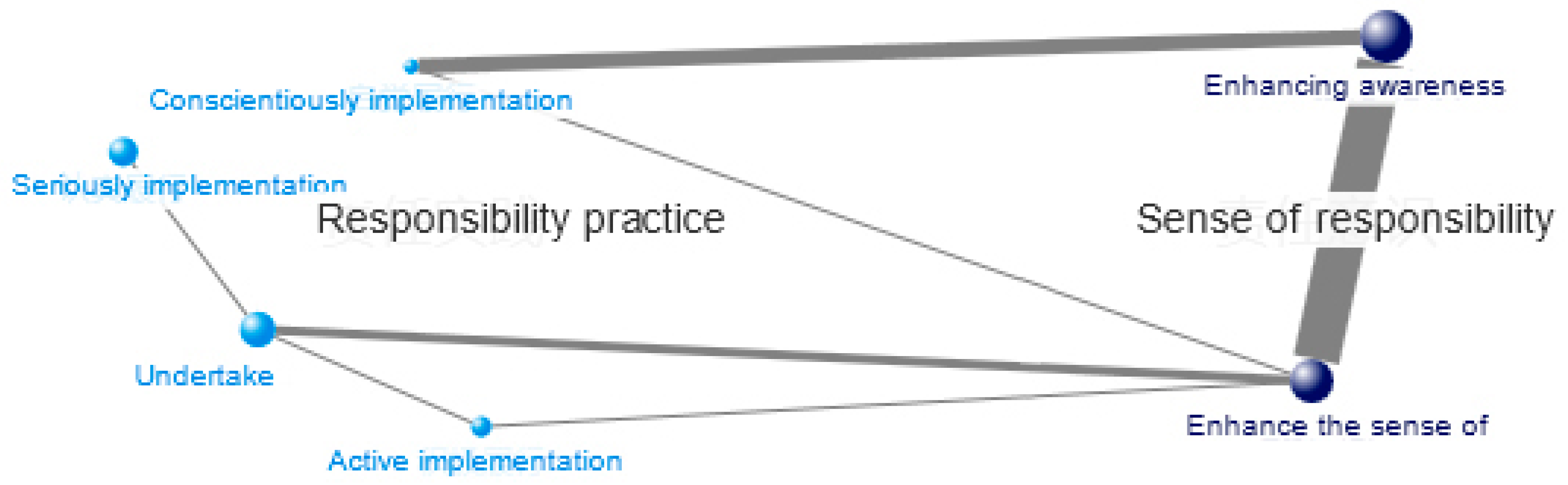

The content of CSR reports of State Grid in 2005–2013 were analyzed by co-words analysis and compared with the evolution of CSR related government policies found in the above analyses to advance understanding of the role of government in guiding enterprises to fulfill CSR, and confirmed the effect of metagovernance on the involved actors.

Table 1 and

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12 show the evolution of State Grid’s CSR.

As

Figure 10 shows, the themes of State Grid in fulfilling CSR focused on social responsibility consciousness in 2005–2007, especially promoting a corporate culture of being social responsibility conscious. According to

Table 1, the CSR of State Grid was in the initial stage, which is consistent with the results of the Chinese government’s policy evolution.

In 2008–2010, although responsible institutions and system were added, social responsibility practices were still the focus.

Figure 11 depicts the network of themes. State Grid was urged to practice social responsibility practices due to the attention of Chinese government. According to

Table 1, State Grid implemented CSR practices to comply with the policy guidance of the Chinese government.

As

Figure 12 shows, in 2011–2013, socially responsible institutions and system attracted more attention, and were comparable with the attention to CSR practices. The trend of attention of State Grid is consistent with national policy guide in this period.

In terms of time frame, evolution stage, and focus of attention, the above results showed that the contents of State Grid’s CSR reports are in line with the signals from the government policy documents on guiding CSR development, and accordingly, verified the influence of government guidance and enterprises’ strategic response to government intentions in the process of CSR evolution in China.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

The number of CSR policies in China increased rapidly in the last decade. Government plays an important role in guiding enterprises to fulfill CSR. This paper verifies the role of the Chinese government in guiding China’s CSR development, empirically presents the overall evolution of the way in which the Chinese government deployed its guiding strategy on CSR, and empirically verifies that metagovernance is the style used by Chinese government to promote CSR development in China.

Based on the collected policy documents on CSR, the quantitative text analysis of policy documents suggests policy intentions and maps policy process, advancing understanding of policy orientation and evolution. With the State Grid as an example for empirical verification via content analysis and co-word analysis, this paper reveals that the evolution of the CSR reports is consistent with the evolution of government policies on CSR, confirming the guidance role of the government in the course of promoting CSR, verifying enterprises’ strategic response to government intentions is an exhibition of corporate adherence to government influence, and demonstrating the power of legitimacy norms signaled by the government [

54,

55].

6.1. Theoretical and Social Implications

This work responds to the call from [

21] for further study on enterprise’s adherence to government signals on politically legitimate behavior and how the interacting mechanism changes over time. Through illustrating the networked effect of China’s policy, this paper empirically answers the central question of metagovernance about the ways in which the organization of metagovernance is carried out. The methodology used in this study may also be applicable to other evolution analysis on policy documents.

It contributes to providing new perspectives for CSR research. Familiar theories to provide perspectives for CSR studies are stakeholder theory, social contract theory, public interest theory, corporate citizenship theory, agency theory, institutional theory and so on. A metagovernance perspective for CSR research is seldom seen. Although enterprise and government are the main actors of social governance, the field of public management emphasizes research on government regulation and public policy analysis, lacking attention to CSR; the field of business management focuses on research on enterprise strategy, management, and operations, having less concern about government policy. The combination of government policy and CSR may contribute to close the existing research gap.

This work provides theoretical and empirical insights into social governance research. Generally speaking, Chinese scholars pay less attention to the theory and mode of metagovernance in the domain of social governance. This paper provides an example of how to apply policy network to explore metagovernance on CSR, providing new clues for social governance system innovation research and China’s further CSR studies.

6.2. Practical Implications

China is in the transition of developing market. Changing and adjusting government functions are very important for the Chinese government to realize successful macroscopic readjustment and control on its market economy. This paper contributes to the understanding of change and adjustment of government functions, providing perspective and methods to analyze China’s hierarchical networked government organizations and policies.

Managers in China need to be aware of the Chinese institutional context in order to obtain sustainable legitimacy. It is recommended that they pay attention to governmental CSR policy and are prudent in responding to the government’s signal to gain sustainable legitimacy and preferential treatment from the government. This paper demonstrates that quantitative text analysis and network analysis can help dig valuable information from policy documents, advancing the knowledge of managers in making decisions, and hence offering a new insight for managers to adopt adaptive strategies and comprehensively consider the payoff and balancing of corporate strategies [

56].

6.3. Research Limitation and Future Research

This study focuses on the guiding role of the government in promoting CSR, but whether the policies would be really implemented or superficially implemented in practice is another problem. The enterprises might only consider their CSR reports as a tactical channel for their own advertisement by reporting only what is good while concealing what is unpleasant. Besides, the interests of local governments and the central government may be in conflict, and the interest in local economic performance may hinder governmental responsibility fulfillment [

57,

58]. These potential obstacles have not been included in the main body of this paper, but the real implementation is an extremely important issue which needs to be deeply analyzed and explored in further study. Furthermore, adopting an institutional theory perspective by incorporating Chinese cultural contexts and Confucianism, which is a dominant philosophy in China, could be a relevant key to contribute to studies on China’s CSR development. In addition, it is significant to perform an international comparison study (e.g., [

59]) for government policies-oriented CSR development.