Taking the First Steps beyond GDP: Maryland’s Experience in Measuring “Genuine Progress”

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Gross National Product “measures neither our wit nor our courage, neither our wisdom nor our learning, neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country, it measures everything in short, except that which makes life worthwhile. And it can tell us everything about America except why we are proud that we are Americans.”Robert F. Kennedy, quoted by Maryland Governor Martin O’Malley [1]

2. Methods

3. Beyond-GDP and Sustainability Indicators: Literature on Impacts, Uses and Obstacles

4. Maryland’s GPI Initiative

4.1. Overview

4.2. Hopes and Motivations

4.2.1. Exploring the Possibilities of a More Complete Picture of Prosperity

4.2.2. Better Policymaking and Data-Driven Governance

4.2.3. Overcoming Policy Silos

4.2.4. Budgeting and Analysis of Policy Options

4.2.5. Promoting the State’s Strengths & a High-Road Economic Strategy

4.2.6. Transformative Goals

4.3. Uses and Impacts

4.3.1. A Low-Profile Initiative

4.3.2. Direct Policy Impacts (Instrumental Use)

4.3.3. Policy Analysis

4.3.4. Political Use

4.3.5. Conceptual Use

4.3.6. Related Initiatives

4.3.7. Exceeding Some Expectations, On the Verge of Something Bigger?

4.4. Obstacles and Challenges

4.4.1. Change of Political Leadership/Running Out of Time

4.4.2. Practical Challenges

4.4.3. Conservative Resistance Lying in Wait

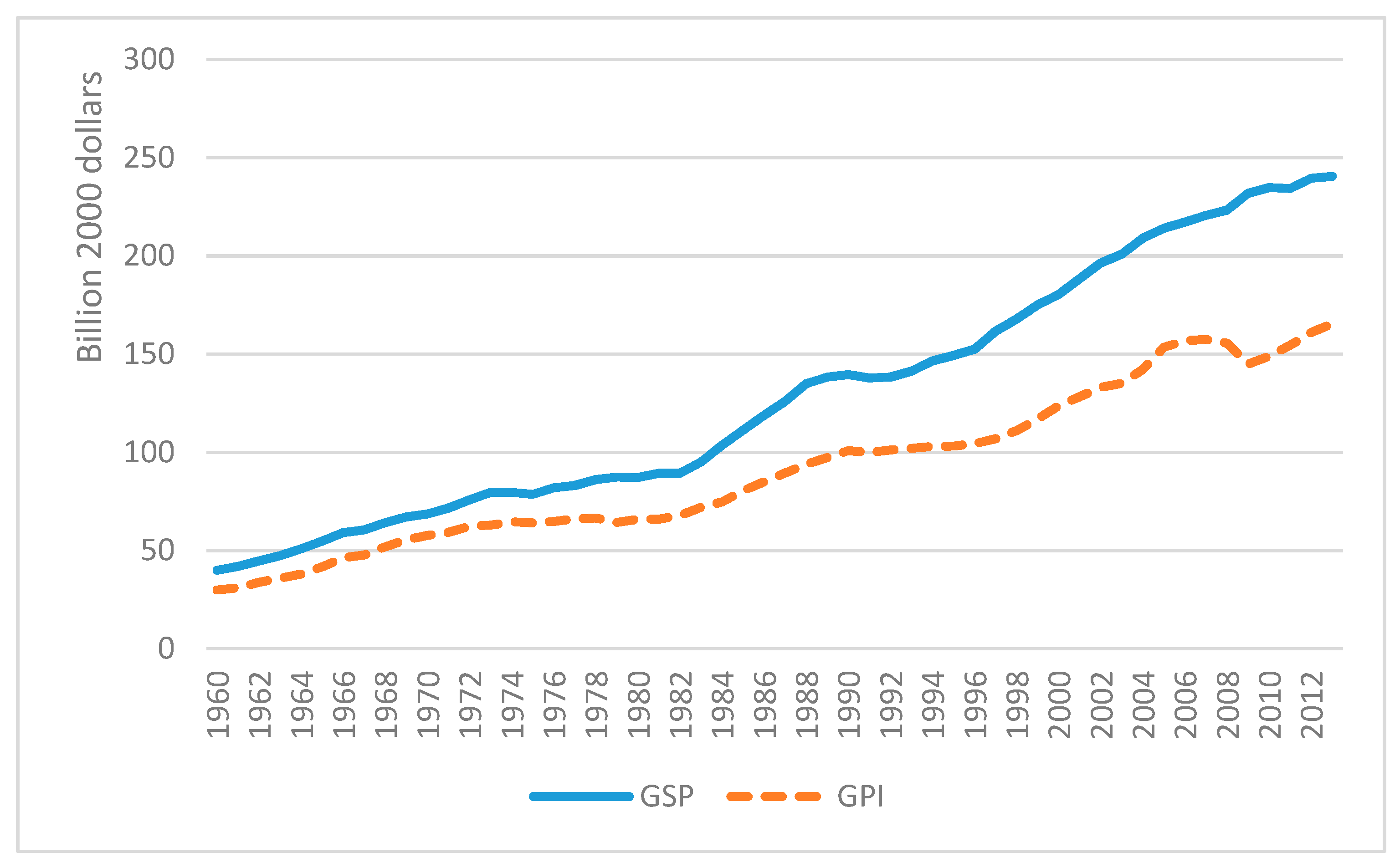

4.4.4. Does the GPI Support the Narrative of Its Proponents?

4.4.5. Other GPI Criticisms

4.4.6. Uncertain Political Constituency

4.4.7. Obstacles to the GPI Note

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Calculating the GPI

| Economic Indicators |

| Personal consumption expenditures adjusted for inequality + Services of consumer durables − Cost of consumer durables − Cost of underemployment + Net capital investment |

| Environmental Indicators |

| − Cost of water pollution − Cost of air pollution − Cost of noise pollution − Cost of net wetland change − Cost of net farmland change, − Cost of net forest cover change − Cost of climate change − Cost of ozone depletion − Cost of non-renewable energy resource depletion |

| Social Indicators |

| + Value of housework − Cost of family changes − Cost of crime − Cost of personal pollution abatement + Value of volunteer work − Cost of lost leisure time, + Value of higher education + Services of highways and streets − Cost of commuting − Cost of motor vehicle crashes |

| Market-Based Wellbeing |

| Household budget expenditures − Household investments − Defensive expenditures (e.g., costs of medical care, insurance and household pollution abatement and security devices) − Costs of income inequality + Public provision of goods and services |

| Non-Market-Based Wellbeing |

| + Services from human capital (services from higher education, library services and value of public art, music and theatre) + Services from social capital (value of leisure time, household labour and internet services) + Services from built capital (services from transportation and water infrastructure and from household goods) + Services from natural capital (ecosystem services from forests, wetlands and Chesapeake Bay). |

| Environmental and Social Costs |

| − Costs of natural capital depletion (non-renewable energy and groundwater depletion, change in the value of productive lands); − Costs of pollution (air, water and noise pollution, GHG emissions, costs of solid waste) − Social costs of economic activity (homelessness, underemployment, crime, commuting, vehicle accidents) |

Appendix B. Interviewees

| Elliott Campbell, Director, Center for Economic and Social Science, Maryland Department of Natural Resources, 23 February 2017 |

| Stuart Clarke, Executive Director, Town Creek Foundation, 12 April 2017 |

| Lew Daly, Director of Policy and Research, Demos, 28 February 2017 |

| John Griffin, former Secretary, Maryland Department of Natural Resources and chief of staff to Governor O’Malley, 1 May 2017 |

| Heather Iliff, President & CEO, Maryland NonProfits, 24 March 2017 |

| Martin O’Malley, former Governor of Maryland, 30 March 2017 |

| Sean McGuire, former Sustainability Policy Director, Maryland Department of Natural Resources, 20 February 2017 |

| Stephen Posner, Affiliate Fellow, Gund Institute for the Environment, University of Vermont 22 November 2016 and 3 May 2017 |

| Matthias Ruth, Northeastern University, former Director, Center for Integrative Environmental Research, University of Maryland, 21 April 2017 |

| John Talberth, President and Senior Economist, Center for Sustainable Economy, 22 February 2017 |

| Anonymous, 1 May 2017 |

| Mairi-Jane Venesky Fox, Regis University, 19 April 2017 |

| Jaime Rossman, Policy Advisor, Washington State Department of Commerce, 17 April 2017 |

| Eric Zencey, Fellow at Gund Institute for Ecological Economics and Coordinator of the Vermont GPI Project, 6 December 2016 |

References and Notes

- O’Malley, M. Genuine Progress. Letters to the People of Maryland. 19 January 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gross National Income (GNI)—Equal to GDP plus net receipts from abroad of primary income (employee compensation and property income), as well as net taxes and subsidies received from abroad—Is another similar measure that has been used increasingly in recent years.

- Van den Bergh, J.C. The GDP paradox. J. Econ. Psychol. 2009, 30, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiszewski, I.; Costanza, R.; Franco, C.; Lawn, P.; Talberth, J.; Jackson, T.; Aylmer, C. Beyond GDP: Measuring and achieving global genuine progress. Ecol. Econ. 2013, 93, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, R.; Kubiszewski, I.; Giovannini, E.; Lovins, H.; McGlade, J.; Pickett, K.; Vala Ragnarsdóttir, K.; Roberts, D.; De Vogli, R.; Wilkinson, R. Time to leave GDP behind. Nature 2014, 505, 283–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Daly, H.E. Growth That Costs More Than It’s Worth. The Washington Post, 30 May 2008; A12. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza, R. How the World’s Economic Growth Is Actually Un-Economic. The Conversation. 8 December 2014. Available online: http://theconversation.com/how-the-worlds-economic-growth-is-actually-un-economic-34362 (accessed on 20 May 2017).

- Lawn, P. The Genuine Progress Indicator: An indicator to guide the transition to a steady state economy. In A Future Beyond Growth: Towards a Steady State Economy; Washington, H., Twomey, P., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan, N.; Halpern, D. Life Satisfaction: The State of Knowledge and Implications for Government; Cabinet Office Strategy Unit: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Easterlin, R.A.; McVey, L.A.; Switek, M.; Sawangfa, O.; Zweig, J.S. The happiness–income paradox revisited. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 22463–22468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Layard, R. Happiness: Lessons from a New Science; The Penguin Press: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Max-Neef, M. Economic growth and quality of life: A threshold hypothesis. Ecol. Econ. 1995, 15, 115–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fioramonti, L. The World after GDP; Polity: Malden, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. Istanbul Declaration. Paris: Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. 2017. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/newsroom/38883774.pdf (accessed on 7 May 2016).

- Stiglitz, J.E.; Sen, A.; Fitoussi, J.-P. Mismeasuring Our Lives: Why GDP Doesn’t Add Up; The New Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Bleys, B. Beyond GDP: Classifying Alternative Measures for Progress. Soc. Indic. Res. 2012, 109, 355–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Layard, R. Why Measure Subjective Well-Being? OECD Observer. 2012. Available online: http://oecdobserver.org/news/fullstory.php/aid/3767/Why_measure_subjective_well-being_.html (accessed on 3 February 2016).

- Talberth, J.; Cobb, C.; Slattery, N. The Genuine Progress Indicator 2006: A Tool for Sustainable Development; Redefining Progress: Oakland, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, S.; Posner, S.; Haake, H. Measuring Prosperity: Maryland’s Genuine Progress Indicator. Solutions 2012, 3, 50–58. [Google Scholar]

- Talberth, J.; Weisdorf, M. Genuine Progress Indicator 2.0: Pilot Accounts for the US, Maryland, and City of Baltimore 2012–2014. Ecol. Econ. 2017, 142, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Natural Resources (DNR). Maryland Genuine Progress Indicator 2.0 Overview; Department of Natural Resources: Annapolis, MD, USA, 2017. Available online: http://dnr.maryland.gov/mdgpi/Pages/gpi2.aspx (accessed on 13 April 2017).

- Gantz, S. Income grows, but not evenly. The Baltimore Sun, 16 September 2016; 1. [Google Scholar]

- Iliff, H. State of Our State: Maryland’s Quality of Life. Address. 11 January 2016. Available online: http://marylandnonprofits.org/Portals/0/Files/Pages/Events/Legislative%20Preview/State%20of%20Our%20State%20Address.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2017).

- Top Earning Towns. Time. 19 September 2014. Available online: http://time.com/money/collection-post/3318911/top-earning-towns-best-places/ (accessed on 20 May 2017).

- Schrank, D.; Eisele, B.; Lomax, T.; Bak, J. Urban Mobility Scorecard; Texas A&M Transportation Institute: College Station, TX, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Demos. Governor O’Malley Hosts First Ever GPI Summit. New York: Demos. 2012. Available online: http://www.demos.org/news/governor-o%E2%80%99malley-hosts-first-ever-gpi-summit (accessed on 30 April 2017).

- Gast, S. Maryland Launches Genuine Progress Indicator. Yes! Magazine. 2 April 2010. Available online: http://www.yesmagazine.org/new-economy/maryland-launches-genuine-progress-indicator (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Governor’s Office. Governor Martin O’Malley Launches Genuine Progress Indicator. News Release; 3 February; Office of the Governor: Annapolis, MD, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- The headline error appears to belong to an overenthusiastic editor rather than the authors, whose original version had a more accurate title (see second item) McElwee, S.; Daly, L. States Are Ditching GDP. Huffington Post. 13 February 2014. Available online: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/sean-mcelwee/states-are-ditching-gdp_b_4734917.html (accessed on 30 April 2017).Daly, L.; McElwee, S. Forget the GDP. Some States Have Found a Better Way to Measure Our Progress. The New Republic. 3 February 2014. Available online: https://newrepublic.com/article/116461/gpi-better-gdp-measuring-united-states-progress (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Bleys, B.; Whitby, A. Barriers and opportunities for alternative measures of economic welfare. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 117, 162–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, A.; Wilson, J. Is it what you measure that really matters? The struggle to move beyond GDP in Canada. Sustainability 2016, 8, 623. [Google Scholar]

- Hayden, A.; Wilson, J. “Beyond GDP” Indicators: Changing the Economic Narrative for a Post-Consumerist Society? In Social Change and the Coming of Post-Consumer Society: Theoretical Advances and Policy Implications; Cohen, M.J., Brown, H.S., Vergragt, P.J., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Porritt, J. Capitalism as If the World Matters; Earthscan: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bache, I.; Reardon, L. The Politics and Policy of Wellbeing: Understanding the Rise and Significance of a New Agenda; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Whitby, A.; Seaford, C.; Berry, C. BRAINPOoL Project Final Report: Beyond GDP—From Measurement to Politics and Policy; World Future Council: Hamburg, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, S.; Morse, S. An analysis of the factors influencing the use of indicators in the European Union. Local Environ. 2011, 16, 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinne, J.; Lyytimäki, J.; Kautto, P. From sustainability to well-being: Lessons learned from the use of sustainable development indicators at national and EU level. Ecol. Indic. 2013, 35, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydin, Y.; Holman, N.; Wolff, E. Local Sustainability Indicators. Local Environ. 2003, 8, 581–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sébastien, L.; Bauler, T.; Lehtonen, M. Can Indicators Bridge the Gap between Science and Policy? An Exploration into the (Non)Use and (Non)Influence of Indicators in EU and UK Policy Making. Nat. Cult. N. Y. 2014, 9, 316–343. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, K. Measuring Wellbeing: Towards Sustainability? Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lehtonen, M.; Sébastien, L.; Bauler, T. The multiple roles of sustainability indicators in informational governance: between intended use and unanticipated influence. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2016, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hezri, A.A. Sustainability indicator system and policy processes in Malaysia: A framework for utilisation and learning. J. Environ. Manag. 2004, 73, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hezri, A.A.; Dovers, S.R. Sustainability indicators, policy and governance: Issues for ecological economics. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 60, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, S. Former Sustainability Policy Director, Maryland Department of Natural Resources. Telephone Interview. 2017.

- Senior state official. Telephone Interview. 2017.

- Anonymous. Telephone Interview. 2017.

- O’Malley, M. Former Governor of Maryland. Telephone Interview. 2017.

- Abdallah, S.; Thompson, S.; Michaelson, J.; Marks, N.; Steuer, N. The Happy Planet Index 2.0; New Economics Foundation: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- UMD MD Adopts Greener. More Accurate Measure of Prosperity. News Release. 3 February; University of Maryland: College Park, MD, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, H.E.; Cobb, J.B. For The Common Good; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Talberth, J. President and Senior Economist, Center for Sustainable Economy. Telephone Interview. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Costanza, R.; Erickson, J.; Fligger, K.; Adams, A.; Adams, C.; Altschuler, B.; Balter, S.; Fisher, B.; Hike, J.; Kerr, T. Estimates of the Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI) for Vermont, Chittenden County and Burlington, from 1950 to 2000. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 51, 139–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Natural Resources (DNR). Maryland Genuine Progress Indicator; Department of Natural Resources: Annapolis, MD, USA, 2017. Available online: http://dnr.maryland.gov/mdgpi/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 27 January 2018).

- Department of Natural Resources (DNR). Governor O’Malley Hosts GPI Summit; Department of Natural Resources: Annapolis, MD, USA, 2013. Available online: http://news.maryland.gov/dnr/2013/06/17/governor-omalley-hosts-gpi-summit/ (accessed on 12 May 2017).

- Smith Hopkins, J. Putting a dollar figure on progress. The Baltimore Sun. 11 September 2010. Available online: http://articles.baltimoresun.com/2010-09-11/business/bs-bz-progress-indicator-20100911_1_gdp-genuine-progress-indicator-national-income (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Department of Natural Resources (DNR). GPI 1.0 Summary 1960–2013; Department of Natural Resources: Annapolis, MD, USA, 2015. Available online: http://dnr.maryland.gov/mdgpi/Documents/GPI1.0summary1960-2013.xlsx (accessed on 27 January 2018).

- Department of Natural Resources (DNR). Maryland Continues to Lead Nation in Genuine Progress Tracking. News Release; 19 September; Department of Natural Resources: Annapolis, MD, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- PBS. Is GDP the Wrong Yardstick for Measuring Prosperity? PBS NewsHour. 28 April 2014. Available online: http://www.pbs.org/newshour/bb/finding-gdp-alternatives-quantify-unpriceable-prosperity/ (accessed on 16 May 2017).

- Campbell, E. Director, Center for Economic and Social Science, Maryland Department of Natural Resources. Interview. Annapolis, MD, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ruth, M. Northeastern University, former Director, Center for Integrative Environmental Research, University of Maryland. Telephone Interview. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, S. Executive Director, Town Creek Foundation. Telephone Interview. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Natural Resources (DNR). Maryland Continues to Measure Genuine Progress. News Release; 22 February; Department of Natural Resources: Annapolis, MD, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Natural Resources (DNR). Maryland Continues to Lead the Nation in Genuine Progress Tracking. News Release; 12 November; Department of Natural Resources: Annapolis, MD, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Natural Resources (DNR). Maryland GPI Grows More Than 2 Percent Last Year. News Release, 1 October; Department of Natural Resources: Annapolis, MD, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley, M. Speech to Genuine Progress Indicators Conference. 14 June; Baltimore, MD, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Talberth, J. Measuring What Matters: GDP, Ecosystems and the Environment; World Resources Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2010; Available online: http://www.wri.org/blog/2010/04/measuring-what-matters-gdp-ecosystems-and-environment (accessed on 30 April 2017).

- Dolan, K. A better way of measuring progress in Maryland. The Baltimore Sun. 30 January 2012. Available online: http://www.baltimoresun.com/news/opinion/oped/bs-ed-measuring-progress-20120130-story.html (accessed on 16 May 2017).

- Iliff, H. President & CEO, Maryland NonProfits. Telephone Interview. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, C. Meet the Big Data Candidate of the 2016 Presidential Race. Business Insider. 11 November 2014. Available online: http://www.businessinsider.com/martin-omalley-2016s-big-data-candidate-2014-11 (accessed on 12 May 2017).

- Perez, T.; Rushing, R. The CitiStat Model: How Data-Driven Government Can Increase Efficiency & Effectiveness; Center for American Progress: Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ceroni, M. Beyond GDP: US states have adopted genuine progress indicators. The Guardian. 23 September 2014. Available online: http://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2014/sep/23/genuine-progress-indicator-gdp-gpi-vermont-maryland (accessed on 16 January 2016).

- Posner, S. Affiliate Fellow, Gund Institute for the Environment, University of Vermont. Telephone Interviews. 2016 and 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wysham, D. The Genuine Progress Indicator: Promoting a Sustainable and Equitable Maryland. Institute for Policy Studies. 22 May 2014. Available online: netransition.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/GPI-webinar-for-Boston-office-2.pptx (accessed on 10 May 2017).

- Center for Sustainable Economy (CSE). GPI Notes—Maryland; Center for Sustainable Economy: Washington, DC, USA, 2014; Available online: http://sustainable-economy.org/gpi-notes-maryland/ (accessed on 10 May 2017).

- Talberth, J. HB 295: Maryland Minimum Wage Act of 2014; Center for Sustainable Economy: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, M.-J.V. Designing for Economic Success: A 50-State Analysis of the Genuine Progress Indicator. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Vermont, Burlington, VT, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley, M. New Deal Inaugural Conference Speech; 18 November; Governor’s Office: Annapolis, MD, USA, 2011.

- Brancaccio, D. Maryland updates Genuine Progress Indicator. Marketplace. National Public Radio, 2011. Available online: https://www.marketplace.org/2011/09/19/business/economy-40/maryland-updates-genuine-progress-indicator (accessed on 18 May 2017).

- Anonymous. Telephone Interview. 2016.

- Clarke, S. Town Creek Foundation Stakeholder Meeting; 14 November; Town Creek Foundation: Easton, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Governor O’Malley Hosts GPI Summit. Introduction and Moderator’s Remarks. 14 June 2013. Available online: https://soundcloud.com/accessdnr (accessed on 15 February 2017).

- Cantori, G. Speed kills, so why raise the limit? The Baltimore Sun. 25 February 2015. Available online: http://www.baltimoresun.com/news/opinion/readersrespond/bs-ed-speed-limit-letter-20150225-story.html (accessed on 18 May 2017).

- Daly, L.; McElwee, S. Why we should abolish the GDP. The Washington Post. 5 June 2014. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/posteverything/wp/2014/06/05/why-we-should-abolish-the-gdp/ (accessed on 18 May 2017).

- Office for a Sustainable Future (OSF). MD-GPI & Value-Added Benefits Scorecard Report: Recommendations, Results, and Feasibility and Viability Analyses; Office for a Sustainable Future: Annapolis, MD, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ruby, H. Fiscal and Policy Note (Revised) for House Bill 295; Department of Legislative Services: Annapolis, MD, USA, 2014.

- Talberth, J.; Wysham, D.; Dolan, K. Closing the Inequality Divide: A Strategy for Fostering Genuine Progress in Maryland; Center for Sustainable Economy & Institute for Policy Studies: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Talberth, J.; Weisdorf, M.A. Economic Wellbeing in Baltimore: Results from the Genuine Progress Indicator, 2012–2013; Center for Sustainable Economy: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Talberth, J. Economic Benefits of Baltimore’s Stormwater Management Plan; Center for Sustainable Economy: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Talberth, J.; Wysham, D. Economic Benefits of Baltimore’s Climate Action Plan; Center for Sustainable Economy: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Talberth, J.; Carter, C.; Wysham, D.; Iliff, H. Minimum Wage Act Reduces Inequality and Represents a $2 Billion a Year Bonus for Maryland’s Economy. News Release, 16 June; Center for Sustainable Economy: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Daly, L. Director of Policy and Research, Demos. Interview. New York, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bagstad, K.J.; Berik, G.; Gaddis, E.J.B. Methodological developments in US state-level Genuine Progress Indicators: Toward GPI 2.0. Ecol. Indic. 2014, 45, 474–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiszewski, I.; Costanza, R.; Gorko, N.E.; Weisdorf, M.A.; Carnes, A.W.; Collins, C.E.; Franco, C.; Gehres, L.R.; Knobloch, J.M.; Matson, G.E.; et al. Estimates of the Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI) for Oregon from 1960–2010 and recommendations for a comprehensive shareholder’s report. Ecol. Econ. 2015, 119, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- We thank an anonymous reviewer for highlighting this point.

- Global Footprint Network (GFN). Making the Economic Case for Sustainable Investments in Maryland; Global Footprint Network: Oakland, CA, USA, undated.

- Farmer, L. Calculating the Social Cost of Policymaking. In Governing; 13 February 2015. Available online: http://www.governing.com/topics/finance/gov-calculating-social-cost-policymaking.html (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Maryland Nonprofits. Quality of Life. 2017. Available online: http://marylandnonprofits.org/advocacypolicy/qualityoflife.aspx (accessed on 20 May 2017).

- Governor’s Office. Governor O’Malley Releases Genuine Progress Indicator Results. News Release; 9 January; Office of the Governor: Annapolis, MD, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pettit, J. Redefining American Progress. National Review. 25 October 2012. Available online: http://www.nationalreview.com/article/331558/redefining-american-progress-jim-pettit (accessed on 8 May 2017).

- Klein, A. How O’Malley whitewashed his state’s poor economy. WND. 7 May 2015. Available online: http://www.wnd.com/2015/05/how-omalley-whitewashed-his-states-poor-economy/ (accessed on 8 May 2017).

- Ehrlich, R. Kitzhaber and How the Left Cooks the Books. National Review. 17 February 2015. Available online: http://www.nationalreview.com/article/398731/kitzhaber-and-how-left-cooks-books-robert-ehrlich (accessed on 8 May 2017).

- The Capital State’s wise men now charting “genuine progress”. The Capital, 6 October 2012; 10.

- Hakim, D. Sex, Drugs and G.D.P. The New York Times. 16 June 2014. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2014/06/17/upshot/sex-drugs-and-gdp.html?_r=0 (accessed on 7 February 2018).

- Posner, S.M.; Costanza, R. A summary of ISEW and GPI studies at multiple scales and new estimates for Baltimore City, Baltimore County, and the State of Maryland. Ecol. Econ. 2011, 70, 1972–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumayer, E. The ISEW—Not an Index of Sustainable Economic Welfare. Soc. Indic. Res. 1999, 48, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anonymous. Telephone Interview. 2017.

- Rosman, J. Policy Advisor, Washington State Department of Commerce. Telephone Interview. 2017.

- Zencey, E. Fellow at Gund Institute for Ecological Economics and Coordinator of the Vermont GPI Project. Telephone Interview. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Dryzek, J.S.; Downes, D.; Hunold, C.; Schlosberg, D.; Hernes, H.-K. Green States and Social Movements: Environmentalism in the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, and Norway; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Natural Resources (DNR). Indicators GPI 2.0; Department of Natural Resources: Annapolis, MD, USA, 2017. Available online: http://dnr.maryland.gov/mdgpi/Pages/Indicators-GPI-2.aspx (accessed on 28 January 2018).

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hayden, A.; Wilson, J. Taking the First Steps beyond GDP: Maryland’s Experience in Measuring “Genuine Progress”. Sustainability 2018, 10, 462. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020462

Hayden A, Wilson J. Taking the First Steps beyond GDP: Maryland’s Experience in Measuring “Genuine Progress”. Sustainability. 2018; 10(2):462. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020462

Chicago/Turabian StyleHayden, Anders, and Jeffrey Wilson. 2018. "Taking the First Steps beyond GDP: Maryland’s Experience in Measuring “Genuine Progress”" Sustainability 10, no. 2: 462. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020462