Abstract

In the discourses on who should benefit from national REDD+ implementation, rights-based approaches are prominent across various countries. Options on how to create viable property rights arrangements are currently being debated by scholars, policy makers and practitioners alike. Many REDD+ advocates argue that assigning carbon rights represents a solution to insecure individual and community property rights. But carbon rights, i.e., the bundle of legal rights to carbon sequestered in biomass, present their own set of theoretical and practical challenges. We assess the status and approaches chosen in emerging carbon-rights legislations in five REDD+ countries based on a literature review and country expert knowledge: Peru, Brazil, Cameroon, Vietnam and Indonesia. We find that most countries assessed have not yet made final decisions as to the type of benefit sharing mechanisms they intend to implement and that there is a lack of clarity about who owns rights to carbon as a property and who is entitled to receive benefits. However, there is a trend of linking carbon rights to land rights. As such, the technical and also political challenges that land tenure clarification has faced over the past decades will still need to be addressed in the context of carbon rights.

1. Introduction

According to the latest United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Conference of the Parties (COP) decisions (UNFCCC Decisions 1/CP 18, 9/CP 19), the proposed international governance structure for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation and the role of conservation, sustainable management of forests and enhancement of forest carbon stocks in developing countries (REDD+) will ultimately take the form of a performance-based mechanism that will provide financial compensation to voluntarily participating developing countries [1]. REDD+ finance shall correspond to measured, reported and verified emissions reductions (UNFCCC Decisions 9-15/CP 19) [2,3] and may come from market as well as non-market-based approaches (UNFCCC Decisions 9/CP 19, 1/CP 17). While REDD+ was initially perceived as a multilevel payment for the ecosystem services scheme (PES) from the global down to local levels, it has been recognized at the national level of several REDD+ countries that REDD+ needs to evolve into a broader suite of policy incentives and mechanisms [1]. Still, monetary benefits from carbon markets are likely to play a central role in any meaningful international scheme to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation. Questions as to how this REDD+ finance will be used in participating developing countries who will benefit at the national and subnational levels and how such benefit streams might be distributed and shared among different actors remain largely unresolved.

In their analysis of equity discourses, Luttrell et al. [4] lay out the main rationales that have been put forward for how benefits should be shared. They highlight the option of rights-based approaches as a prominent discourse across various potential REDD+ countries (see also [5]). Therefore, it is not surprising that options on how to create viable property rights arrangements for the benefits to be distributed under REDD+ are currently debated by scholars, policy makers and practitioners alike. Here, we draw on Bromley [6] (p. 2) to define a property right as the “claim to a benefit stream that the state will agree to protect through the assignment of duty to others who may covet or somehow interfere with this benefit”. In this article, we highlight several options for linking monetary benefits from REDD+ to existing property rights regimes. For example, linking benefits to the ownership right to carbon sequestered and stored in trees, or to the rights to use a forest, or to the rights to the land where the forest is located [4,7,8].

The central argument of this paper is that clarity over tenure and resource rights in tandem with the carbon asset is critical to prevent disruptive conflicts between competing stakeholders within REDD+ countries [9,10]. Such conflicts will propagate uncertainties and further complicate transactions between sellers (“providers”) and buyers (“beneficiaries”) of carbon ecosystem services (ES) provided by forests [11]. Further, existing initiatives already operating under voluntary carbon markets apply existing laws as a “proxy” for carbon rights regimes. They face the risk that future changes in the law may overrule their present right to carbon benefits [10]. We assess the existing approaches in emerging carbon-rights legislations in five REDD+ candidate countries (Peru, Brazil, Cameroon, Vietnam and Indonesia) to get a sense of possible implications that the allocation of carbon rights has for stakeholders in REDD+ countries. To preview our main results, we find that most countries assessed have not yet made final decisions as to the type of benefit sharing mechanisms they intend to implement; there seems to be a trend to linking carbon rights to the rights to land with some variation among countries since there is an overall lack of clarity about who owns rights to carbon as a property and who is entitled to receive benefits. While there is a fluid discussion on the latter, the issue of who bears responsibilities for the permanence of emissions reductions is almost non-existent.

In the following Section 2, we give some background information to highlight the need for carbon rights clarification under REDD+ benefit sharing. In Section 3, we review the literature on the nature of carbon rights to clarify what carbon rights are and who can theoretically own these rights. We then give an overview of how carbon rights have been characterized under different legal arrangements in the five countries analyzed and highlight the assumptions and interests behind the way carbon rights are being conceptualized (Section 4). In Section 5, we discuss possible practical implications of varying conceptualizations of carbon rights. The paper concludes by discussing policy implications of our findings.

2. Relevance of Carbon Rights for REDD+ Benefit Sharing

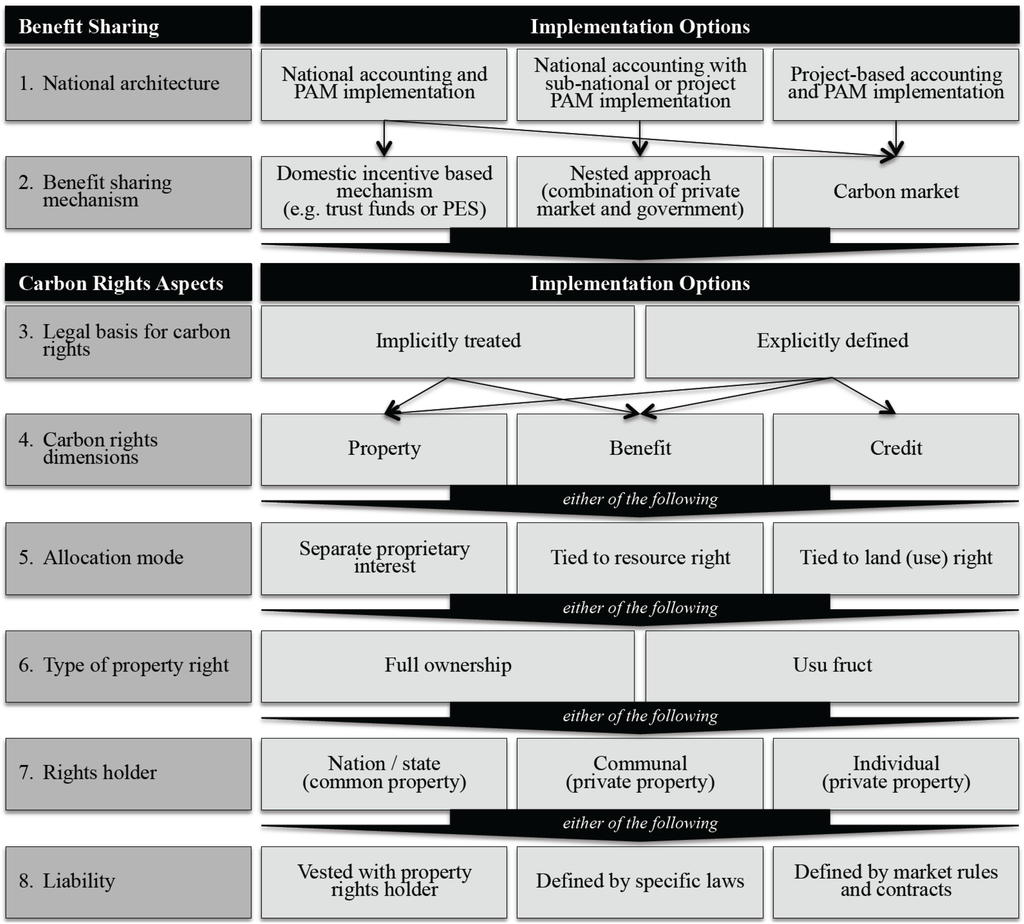

The UNFCCC COP decisions on REDD+ reaffirm that both international market and non-market-based mechanisms are on the table for generating and sharing monetary benefits from REDD+ activities (UNFCCC 9-15/CP. 19; 1/CP. 17). To link these mechanisms with national systems, different approaches to REDD+ benefit sharing within participating countries are being discussed: (I) national accounting and implementation; (II) national accounting with sub-national or project implementation; (III) project-based accounting and implementation [2,7,8,12]. Depending on the type of benefit sharing mechanism and governance levels involved, regulatory systems are needed at the international, national and sub-national levels that define and allocate the ownership of carbon in light of national or local conditions [8,11,13] (Figure 1).

In case performance-based REDD+, “national approach” national governments, representing their countries as parties to the Convention, will make voluntary commitments to reduce carbon emissions, which are measured, reported and verified at the national level (Option I) [14]. To achieve emissions reductions, national governments can implement various policies and measures (PAMs) designed to change the behavior of forest stewards, such as increasing protected areas through direct regulation, establishing new taxes or domestic PES systems [1,8]. Accordingly, national governments are compensated through an international mechanism for the results of these PAMs if they succeed in reducing emissions reductions. Such a “national approach” would be compatible with an international non-market mechanism, such as an international fund, under auspices of UNFCCC. However, it can also be adapted to become part of a compulsory carbon market between nation states comparable to the existing emissions trading scheme under Article 17 of the Kyoto Protocol. If performance-based REDD+ is based on national accounting and implementation, entitlement to carbon at local levels may not be directly essential for international trades between states since national governments would directly hold the rights to benefit from carbon emission reductions and the requisite responsibility to realize them.

Figure 1.

Framework for the assessment of national carbon rights legislation.

In contrast, Options (II) and (III) would allow for a direct involvement of public or private entities through market-like mechanisms at sub-national levels. These would include proposed jurisdictional scale REDD+ credit trading systems like the agreement between the federal states of California (USA) and Acre (Brazil), and also local initiatives, where buyers of emissions reductions may interact directly with forest stewards via voluntary carbon markets. In this case, project partners need to know who manages and controls the forest. It is important to ensure that those who are responsible for activities that may lead to emissions reductions have the long-term right to conduct such activities and that they can be rewarded in case of successful reductions or held responsible in case of failure [10,11]. In order for forest actors to claim the rights to benefits in performance-based mechanisms, especially in market-oriented REDD+ initiatives, they will need to establish that they have property rights to the carbon sequestered in forests or the right to benefit from activities that lead to carbon sequestration. Furthermore, a tradable commodity or “credit”—needs to be defined in order to attract capital from the private sector through voluntary or, in the future, compulsory national or international carbon markets, so that it can be bought and sold without ambiguity.

Although Approaches (II) and (III) already exist in the voluntary carbon markets (for the extent of the voluntary carbon market see [15]), no decisions on the international level on how carbon property rights are to be defined or handled have been made so far [10]. If UNFCCC REDD+ is designed as an international market mechanism, it is likely that the rules of the Kyoto Protocol’s Marrakesh Accords will serve to guide this process [7,16]. However, the allocation and enforcement of property rights over natural resources is subject to national sovereignty. Domestic laws will determine who owns the carbon itself and the carbon sinks and whether this will include the right to benefits. Furthermore, if credits for emissions reductions are introduced, eligible activities and social and environmental standards will need to be defined by a clear national legislation, as they may differ from existing Clean Development Mechanisms (CDM) or voluntary market definitions [10].

3. Conceptualizing Carbon Rights

The concept of “carbon rights” is often poorly defined, which leads to diverging views on the subject of the “carbon right” [8,11] and a lack of a single, widely accepted, operational definition of the term in the literature (see e.g., [7,17,18]). Here, we conceive of the sequestration and storage of atmospheric carbon, that is the carbon taken up from the atmosphere and converted through photosynthesis to carbon stored in biomass, as a global scale ES, i.e., direct and indirect benefits humans derive from ecosystems [19,20,21]. Different dimensions of rights can be attached to these ES and the rights can be linked to existing property rights.

3.1. Carbon Rights Dimensions

To establish rights to benefit streams and assign responsibilities for the provision of carbon ES, property rights need to be clarified with national or sub-national laws, or by jurisprudence [11,22]. Thus, we first discuss different subjects of rights to carbon, that is, the question of the scope and the object of the right. We build on the debate in the literature and distinguish between three dimensions of carbon rights.

First, following Peskett and Broding [8], we define rights to “carbon as property” as the bundle of rights and obligations to the resource or good itself: the carbon sequestered and stored in the biomass of the trees that make up a forest, independent of any existing incentive or disincentive-based policy instrument. However, owning carbon as a property does not convey much value in itself. Thus, to incentivize the provision of carbon ES, a variety of policy instruments are being considered to support the provision of these services. These policies can be designed strictly according to a “polluter-pays” principle, i.e., in a way that holds carbon property rights-holders accountable for carbon outcomes such as taxes and the regulatory cap in a “cap-and-trade scheme”, or these policies follow a “provider gets” principle for example in the form of subsidies or PES schemes. We consider these rights to be compensated or rewarded for the provision of carbon sequestration and storage services as a separate dimension of carbon rights [23,24,25]. Finally, if policy instruments are in place that reward the provision of the sequestered carbon, an option is the commodification of the service, that is “the inclusion […] into pricing systems and market relations”, such as national or international emissions trading regimes [26] (p. 620). In that case, further distinction can be made between “rights to benefit”, and the derivative “rights to carbon credits” as “the tangible financial expression of the carbon rights” [7] (p. 23). A right to a “carbon credit”, can be understood as the title to a tradable credit (a commodity) which needs to be defined by international and national legal acts (compulsory carbon market) or contractual (voluntary carbon market) standards [8,27]. The definition of credits usually includes the specification of the unit, the duration of validity, eligible activities to obtain them, reference emissions levels, and social and environmental safeguards [7,10,11].

3.2. Linking Carbon Rights to Existing Tenure Rights

Different ways exist to institutionalize the three carbon rights dimensions. Countries may choose to pass an explicit carbon rights legislation [11,28] or to modify and adapt existing natural resources or forest laws. However, “specific domestic laws on carbon rights in REDD+ are not a pre-requisite” for defining carbon rights [8] (p.10), [23]. In fact, many countries will deal with carbon rights implicitly under existing laws [11]. When no specific carbon legislation exists, analogies can be drawn from existing resource laws such as land and forest or resource tenure, as for example for NTFPs or ES [8,11,29]. In that case clarification by jurisprudence is needed to verify legality of these analogies.

Carbon rights, whether explicitly or implicitly defined, may follow existing property rights regimes. One option is to define the sequestered carbon as an independent proprietary interest, which is the case in New Zealand and Australia [11,23,25,30,31,32]. In this case the right to the sequestered carbon, which is physically contained in land, trees and soil, does not necessarily have to coincide with the property rights over the physical resources. It can be separated and defined as a self-contained, intangible asset with a monetary value—similar to an intellectual property right, a company’s brand value or a title to a mortgage [33]. Instead, carbon rights may theoretically be tied to rights to the trees that store the carbon. In Cameroon, for instance, ownership of trees does not necessarily coincide with the right to land [31]. Yet the rights to carbon may also be tied to the rights to the land the trees that store carbon stand on or even to the rights to the goods and services which are being produced on the land, for example timber, NTFPs or ES.

Land tenure has an important influence on how benefits from forests are shared because it helps determine which actors have the right to carry out activities and claim benefits from a particular area of land and its associated natural resources [34]. The reasoning in common-law for tying carbon rights to land use is that because forest carbon sinks grow on land, they are a natural part of the land, and therefore “those who possess rights to land could be assumed to hold rights to the carbon sinks and therefore the carbon” [24] (p. 11). Under civil law, Wieland [11] (p. 10274) explains that “carbon may be considered a ‘fruit’ tied to the estate and hence the property of whoever owns the land“. However, in many countries the rights to resources such as timber or NTFPs are separated from the right to land through the definition of use rights, such as timber or mining concessions in Peru or Cameroon. Following this logic, carbon ownership may belong to holders of the rights to the resource [12,24].

Rights to the land or the resource that establish the right to carbon property or the benefits do not necessarily require full ownership of the property. In fact, the majority of forest tenure regimes in predominantly state owned tropical forests, such as Vietnam, Peru or Cameroon, rarely transfer the full bundle of rights [35]. More typically, national governments like Brazil retain or restrict alienation rights while recognizing the rights of indigenous peoples and local communities to use and even co-manage forest resources [36]. Similarly, carbon rights allocation could also be considered a “resource tenure”, comparable to the civil law notion of the right of usufruct [17]. This is the right of reaping the fruits (fructus), i.e., income or benefit from someone else’s property, without destroying or wasting the subject over which such a right is extended [12,37]. Usufruct is usually conferred for a limited time period, although long-term use rights, as for example for indigenous people on public lands in Brazil, do exist. Policy instruments that grant usufruct rights amongst others encompass conservation easements such as profits-á-prendre, conservation concessions (leases), or encumbrance [7,8].

Ownership and use rights may belong to an individual, a group, such as a community, the entire people, the nation or the state. Thus, depending on how rights to carbon and benefits are explicitly or implicitly defined, the resource can be transformed either into a publicly owned commodity or private property or communal property [25,38].

3.3. Liability

To date, the debate on carbon rights mainly focuses on rights to the property and the rights to benefit. However, rights most often also come with obligations. The rights to carbon as a property, for example, may include the obligation of sustainable and permanent provision of carbon storage, i.e., the continued existence of forest carbon stocks [39]. Furthermore, the right to benefit from emissions reductions can come with liabilities in case of unintended deforestation. Thus, carbon rights legislation just like property laws or contracts must spell out who bears the burden in case responsibilities not being fulfilled, i.e., failure to generate agreed emissions reductions due to e.g., fires, pests or droughts [32]. For the international level of REDD+, different options to cope with the distribution of liability have been discussed (see e.g., [40]). Amongst the options are temporary carbon credits comparable to the rules for CDM A/R credits [40,41], the establishment of an independent banking mechanism in which a certain amount of verified emissions reductions from REDD+ is placed for a certain time period as a security (as a type of buffer), and the involvement of the private insurance sector [39,40]. The question of liability in REDD+ has not been discussed in depth for the national or sub-national levels. However, a prominent opinion is that whoever claims ownership over carbon as a property or rights to benefit should be held responsible in case of failure to meet emissions reductions commitments [12,42].

4. Carbon Rights in Selected Countries

The following section assesses the status of carbon rights legislation in five REDD+ pilot countries. The aim is to highlight the approaches taken and to predict the practical implications these may have (Figure 1). The conceptual analysis has shown that depending on the different options of international and national REDD+ benefit sharing mechanisms there is a need for clarifying carbon rights institutionalization at national and sub-national levels. Thus, reviewing the national approaches to REDD+ benefit sharing will give a hint as to which dimensions of carbon rights need to be incorporated in national legislations. If an explicit carbon rights legislation does not exist, the analysis of existing natural resource laws can give valuable insights into how carbon rights might implicitly be defined. It is of particular interest to distinguish whether carbon is treated as a separate proprietary interest or rather tied to the right to land or to the right to the natural resource physically containing it. A clear discernment of the case at hand can give valuable insights into who will be a potential beneficiary of incentives distributed for the provision of carbon ES. Furthermore, this will help answer the questions of what obligations come along with this right and who is held liable in case of failure to provide the carbon ES.

4.1. Peru

Peru takes a “nested approach” to REDD+ benefit sharing with national accounting and sub-national or project level implementation [11]. Eventually, the goal is to link this nested structure to performance-based incentives from international carbon markets and, potentially, other revenue sources. Currently, the Peruvian Ministry of Environment (MINAM) and some regional governments are taking steps to develop a harmonized benefit sharing system that works across multiple levels of governance.

While the strategy has not yet been formally articulated, preliminary presentations from MINAM suggest that once a national approach is adopted, monetary benefits will flow from the national government to regional governments based on each region’s contribution to deforestation and forest degradation reductions and also to maintenance of national carbon stocks. Regional governments would then disburse payments to sub-regional actors including indigenous communities, private landholders, concessionaires and government actors managing protected areas and uncategorized forests. Of these benefits, a certain percentage must be allocated to regional and local governments. If such an approach is adopted, the distribution of benefits will be allocated based on the principle that sub-national jurisdictions are accountable for and entitled to benefit from carbon that is stored on lands within them.

Apart from these steps in the development of a coherent benefit-sharing framework for REDD+, there are other laws and initiatives that have a bearing on revenues from forest conservation, carbon and ecosystem services. While these policies are not explicitly about REDD+, they have implications for carbon rights and therefore future REDD+ benefit sharing schemes.

First, in 2010, Supreme Decree N. 008-2010-MINAM established the National Forest Conservation Program (Programa Nacional para la Conservación de Bosques, PNCB) as a voluntary national commitment to conserve 54 million hectares of forest through forestry conservation incentives agreements with the sub-national governments as well as native and peasant communities. So far, approximately $1.7 million USD have been disbursed annually to 2325 participating families. This process has provided a possible basis for disbursing funds to households, communities, and governments for conserving forests and their associated ES.

Second, a directive proposed in 2013 by the National Protected Areas Entity (SERNANP)—which is housed under MINAM—posits that SERNANP is the owner of carbon and benefits derived from it in forests and lands within its protected areas and their buffer zone. SERNAP therefore not only owns the carbon in these areas but also holds the right to benefit from it, including by way of selling credits. The implication is that REDD+ projects operating in natural protected areas that obtain certified emissions reductions—irrespective of the certification mechanism—must now enter into agreements with SERNANP to determine how benefits are shared. This directive would grant SERNANP the authority to transfer rights and certificates to third parties, including REDD+ project implementers. Benefits generated by the sale of carbon credits will be deposited into a bank account created for the project and controlled by the central government. Any interest accrued from such accounts will be transferred to a special fund to support management of the natural protected area and its corresponding buffer zone. While SERNANP would be the owner of carbon rights generated in natural protected areas under this directive, rights currently held by third parties with administrative contracts—such as NGOs who have received contracts from SERNANP to manage or co-manage protected areas—would not be retroactively transferred [43].

Third, to date there have been several legal acts that arguably form an implicit basis for defining carbon rights. Article 66 of the 1993 constitution states that natural resources, including renewable and non-renewable resources, are the national patrimony of Peru. The constitution outlaws private property rights over the “source” of these natural resources such as natural forests [11,44]. The state may not trade natural resources but may grant use rights and concessions to third parties [44,45]. However, the “fruits” and “products” or benefits derived from these natural resources belong to the holder of the concession once they are extracted [11]. The implication is that there is a legal basis for concession holders to claim rights to ecosystems services provided by resources within concessions, potentially including carbon sequestration. Related to this, according to Article 3 of the Natural Resources Act, natural resources refer to components of nature that can be used to satisfy human needs and that have an actual or potential value on the market. Carbon sequestration arguably satisfies all of these conditions and MINAM consequently argues that carbon sequestration is an ecosystem service derived from natural resources that are part of Peru’s national forest patrimony [11].

Fourth, a new law on PES enacted in June of 2014 along with the new Forestry will alter the current legal status of carbon rights in Peru. The new “Mechanisms for Payments for Ecosystem Services Law” (Ley de Mecanismos de Retribución por Servicios Ecosistémicos, MRSE), enacted in June 2014, defines ecosystem services (ES) as direct or indirect economic, social and environmental benefits that people obtain from the good condition of ecosystems. Carbon storage is explicitly referred to as an ES by this law. Article 3 of MRSE states that providers of the ES can be private or public and may include both formal and informal rights-holders. These include not only land title holders and concessionaires, but also NGOs that hold administrative contracts over natural protected areas, and others that MINAM recognizes. However, the legislation does not address cases of overlapping rights. For instance, it remains disputed who owns carbon within protected areas where there are also NTFP concessions [11].

Overall, several key questions remain. First, who will benefit? The new PES law will align carbon rights with a broad range of other property rights, including those held by private title holders, possessors, and “other actors that MINAM recognizes”. Given that the to date the Ministry of Agriculture has been responsible for managing forestry resources through its Directorate of Forests and Wildlife, this law may empower MINAM to allocate carbon rights. Moreover, the rights holders are specified as users and owners of land for “alternative uses,” title holders who have been granted title on the basis of conducting “sustainable use” activities and actors operating in national parks. Certain actors may be more likely to meet these criteria than others. For example, it is not clear how easy it will be for smallholder farmers, especially those who do not have land rights by virtue of membership in a native community, to meet these standards and be considered carbon rights holders.

Second, what obligations come with the ownership rights? Given the criteria for carbon rights holders set forth in the PES law, there may be incentives for actors to meet “alternative” and “sustainable” use criteria to gain rights to carbon. The extent to which this incentive creates a real obligation to change land use behaviors, however, remains to be seen.

Finally, if a nested approach to benefit sharing is adopted, what implications does this have for projects that aim to sell carbon credits on the voluntary market? Currently, projects can pursue independent certification of emissions reductions through standards like the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS). According to respondents from MINAM, Peru, unlike many other countries, aims to allow projects to continue to sell carbon credits on voluntary markets even as the country moves towards a national system aimed at compatibility with international and national compliance markets. The degree to which such a national system oriented towards compliance markets, especially with benefits distributed through regional governments, is compatible with projects that verify their emissions reductions independently remains unclear.

4.2. Brazil

Brazil’s draft National REDD+ Strategy follows an approach of national accounting of emissions reductions with decentralized implementation of benefit sharing. Sub-national agencies and actors will be able to receive and re-distribute benefits relative to achieved reductions in deforestation. With such an aim, they will apply their own criteria for benefit sharing under the guidance a REDD+ national entity, to be created by the strategy [46]. The draft strategy aims at integrating and coordinating different measures already being implemented to reduce deforestation and includes incentive based mechanisms as an additional element.

Brazil is a Federal Republic, a union of twenty-six states, with its territorial extension divided into six natural biomes: Amazon, Cerrado (Brazilian savannah), Atlantic Forest, Pantanal (wetland) and Pampas. Brazil opted to set its REDD+ reference levels by biome, starting with historical deforestation data from the Amazon monitoring since 1988 [47]. The measurement and verification of results in emissions reductions from deforestation and degradation will initially be at the biome level, advancing later into a national accounting with the development of monitoring systems to other biomes different than the Amazon [46]. To date the main REDD+ BSM at federal level is the Amazon Fund, a performance-based mechanism created in 2008. The fund aims at raising donations for non-reimbursable investments in efforts to prevent, monitor and combat deforestation, as well as to promote the preservation and sustainable use of forests in the Amazon Biome [48]. Fundraising for the Amazon Fund is linked to the reduction of emissions of greenhouse gases from deforestation, that is, it is conditioned to the reduction of the annual deforestation rate. How the fund will measure the attribution between funds and reductions, however, is still unclear. The results achieved in terms of reduced emissions are rewarded through donations from developed countries, currently Norway and Germany, and the Brazilian Company Petrobas. Donors in return receive certificates that are nominal, non-transferable, and do not generate carbon rights or REDD+ claims of any nature. In addition to the Amazon Fund, federal legislations are proposed related to REDD+ and the establishment of a national PES scheme. Both of them consider a decentralized distribution approach to benefit sharing. At the same time incentive based mechanisms such as PES are already being introduced at state levels and a number of state, municipal and project levels REDD+ initiatives are being implemented [4].

Until now, a legal act specifying the nature of rights to carbon is missing at the federal level. For private land “general provisions of constitutional and civil law do provide some guidance” about who owns carbon as a property [49] (p. 260). “According to the Brazilian Civil Code, ownership rights include the right to use, dispose of, and defend property against unlawful possession. The Civil Code further states that the accessories or products derived from a “physical asset” belong to its owner unless otherwise established by law or contract” [49] (p. 261). Butt et al. [49] (p. 262) therefore conclude that any benefits or credits resulting from REDD+ should belong to “the owner (or rightful holder) of the physical asset, the forest that generates the climate benefit”, following the approach where benefits are tied to resources.

For private lands, the federal government in its draft REDD+ strategy has indicated that the main instruments to reduce deforestation would be positive incentives that can generate tradable rights [46]. These rights would be distributed and traded based on established limits imposed by federal and state legislations on natural resources use, such as the new Forest Law. Examples of these rights include forest quotas and forest asset titles. Other modalities of positive incentives include environmental subsidies, such as PES, and tax reforms to reduce deforestation. Finally, the draft REDD+ strategy adopts social and environmental principles and criteria constructed by civil society actors in 2010, stating that benefits resulting from REDD+ initiatives should be distributed to those with land or resource rights and the ones who promote REDD+ activities and generate reductions [50]. In this sense, although not specified at the federal level, ownership of carbon rights would likely follow the ownership of the land or resources and provision of emissions reductions.

However, for public forests, the Law on the Management of Public Forests, which, amongst others, regulates the concession and use of public forests, prohibits the commercialization of forest management related carbon benefits, except for reforestation activities [8,49]. It “contains an explicit reference to the state’s legitimate entitlement to forest carbon from concessionaires and it is thus likely that the state will also claim the carbon rights from government-administered areas” [12] (p. 332). These findings are in line with an analysis of the Brazilian readiness strategy by Larson et al. [42] concluding that Brazil leans towards linking formal land ownership with carbon rights.

An exception to this basic rule is the case of indigenous lands (which occupy 21.5% of Brazilian Amazon). Even though indigenous lands are federal land, the Federal Constitution establishes that indigenous people have permanent rights to property and exclusive use of resources on the lands on which they live. Based on these constitutionally guaranteed rights and the historic role of indigenous people in conserving their territories, civil society organizations argue that carbon rights and benefits from marketing of environmental services should accrue to indigenous people [51,52]. A federal legal opinion (AGU-AFC-1/2011) holds that provision of ecosystem services associated with indigenous territories could be constitutionally subject to commercial agreements on the part of indigenous groups and that the rights to carbon benefits and potential credits generated in indigenous lands belong to indigenous people and not to the federal government. “There is, however, still some debate as to whether indigenous peoples would have autonomous legal capacity to negotiate and conclude carbon-related agreements and to what extent they would need to be assisted by the State for participating in REDD+ projects (Telles do Valle and Yamada, 2009; Takacs, 2009)” [8] (p. 22).

In the different federal states, on the other hand, diverging carbon rights legislation initiatives started to operate in the absence of any federal strategy or legislation [53]. The states of Mato Grosso, Acre, Amazonas and Tocantins have already implemented climate and conservation related laws. In the case of Acre and Tocantins, carbon rights generated in public lands belong to the state. In the case of the conservation units (such as sustainable development reserves and protected areas) in the state of Amazonas, this right was temporally transferred to the Amazonas Sustainable Foundation (FAS). The foundation is responsible for managing different conservation units in the state through the Bolsa Floresta Program, a state level PES program. However, FAS needs to apply all financial resources generated through the negotiation of reductions in the management of conservation units in the state [54]. So far, FAS has been negotiating emissions reductions agreements in the voluntary market with actors from the private sector. ES providers, defined by law as the ones who actually generate the services such as traditional communities living in these areas, have rights to access the financial resources generated by reductions in all mentioned states. This access needs to be approved by governments and providers need to be legally based in the lands where services are being maintained, restored, or improved [53].

Recently, the federal states of the Amazon region presented a proposal [55] on how to distribute credits or titles generated by emissions reductions, which they call REDD+ units (U-REDD+), following a nomination originally proposed in the 2009 REDD+ Bill 5.586/2009, which still is under debate at the National Congress (see [56]). According to the proposal, the distribution would occur among diverse stakeholders involved in the process of reducing deforestation, namely governmental or non-governmental agencies, rural producers or indigenous populations and traditional peoples. The division of U-REDD+ proposed would direct 20% to the federal government and 80% to the states. The proposal stresses that the distribution of U-REDD+ to the states does not signify a “pass-through” or use right to the state governments as they should have or establish a specific regulation that determines how REDD+ should be managed at the state level and how its potential benefits would be distributed. They propose the U-REDD+ should be allocated based in the concept of stock-flux, where flux refers to the contribution of each state to the reduction of deforestation (based on its historic rates of deforestation) relative to the reduction of deforestation verified for the entire Amazon biome and stock refers to the quantity of carbon stored in the forested area of the state in relation to the forested area of the whole Amazon biome [55].

At this point, states and federal governments are the actors most likely to benefit from carbon rights generated from REDD+ activities, as majority of lands are public in Brazil (76%). How these rights will be allocated from federal and state levels to local actors is still to be clarified. Considering that emissions reduction will occur on the ground, it is crucial to determine how benefits will reach these actors. Even if they do not have ownership rights to carbon as a property, they should have well defined rights to benefits generated from carbon reductions. One may argue that local actors would not be able to manage and negotiate carbon rights, but a clear strategy for accessing benefits is needed and this process should be free of bureaucratic instances and with high levels of participation in order to guarantee more social oriented distribution and allocation of financial resources. Finally, the definition of obligations that come with carbon rights and the liability of failure in reducing emissions are important elements in a national REDD+ strategy. However, they are overlooked in current debates and remain unclear both at national and sub-national levels.

4.3. Cameroon

Cameroon’s approach to national REDD+ benefit sharing is not far advanced. The 2012 Forest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF) Readiness Preparation Proposal (R-PP) merely states that the national BSM will be based on the experience of other revenue sharing mechanisms currently in place [57] such as the redistribution mechanism of forest logging fees (referred to herein by its French acronym, RFA, redevance forestière annuelle). At the same time the R-PP recognizes the clarification of carbon ownership as an important aspect for national scale benefit sharing [57]. Given the current approach to national benefit sharing, it seems unlikely that a national carbon market with tradable carbon credits will be established. However, emphasizing the fact that REDD+ will draw on experiences from existing BSM hints to the establishment of an incentive based mechanism, so that the questions of who owns carbon as a property and who is eligible for receiving benefits needs clarification.

Cameroon—a country with a civil law system—does not have a specific legislation on carbon rights to date. Based on the current legal status of other natural resources, the Cameroonian lawyers Sama and Tawah [58] assert that absorbed or avoided carbon can be classified as a natural resource. In most cases the laws on natural resources link ownership over the resources to the ownership of the land. Cameroon’s land property system is based on the 1974 Land ordinance which makes a distinction between: (1) Public domain (state property); (2) Private land; (3) National Domain or National Land (nation property). Such a distinction has an impact on forest law: According to the 1994 Forest law, Cameroon has two main types of forests: (a) Permanent forests that comprise State Forests and Council Forests; (b) Non-permanent forests that comprise communal forests, community forests and private forests [59,60]. The natural resources, such as all genetic resources (1994 Forestry Law, Section 12), all water resources in the national territory (1998 Water Resources Act) and all mining resources except for those covered by personal exploitation permits (Mining Code, Section 2), found in state or communal forests belong to the state; those on national land, which is administered by the state, belong to the Cameroonian nation [61]; those found in council forests belong to the council and the resources in private forests are owned by individuals.

Cameroon’s legal system does not make a distinction between trees and the elements such as carbon stored in them. By focusing on forestlands and examining the present status of lands and the absence of any clear distinction between rights over the trees that store carbon and rights over carbon per se, Part I, Section 7 of the 1994 Forestry Law states that “the State, local councils, village communities and private individuals may exercise on their forest and aquacultural establishments all the rights that result from ownership subject to restrictions laid down in the regulations governing land tenure and State lands and by this law” [62]. Given that there is no distinction between the owner of the carbon and the resources (the tree storing carbon) and that the owner of the land owns the resources, the owner of carbon may, by implication, be the owner of the land [57,58]. Consequently, the right to carbon as a property and the right to benefit from state and communal forests would belong to the state whereas the right to carbon on community and private forests would belong to the owners of these forests, and the carbon on council forests and national land would respectively belong to councils and to the nation managed by the state.

Cameroon has established a system of different use rights for the exploitation of natural resources in state and national forests such as logging concessions. If, as asserted above, carbon ES are considered as “resources”, use rights for these ES would need to be defined to claim benefits for their provision. Currently, the state can grant usufruct rights to occupants of national land. Local communities that have not registered their land are considered to have usufruct rights. Furthermore, the law provides that customary communities have the right to hunt wildlife, and to collect and gather NTFPs.

Each provisional land concessionaire has an obligation to put to valuable use the area granted to him by planting perennial crops such as palm oil, sugarcane, banana, rubber etc. Whether REDD+ activities would be considered as such “valuable use” remains unanswered to date. It is only after five years of evidence of productive use that the state will provide a land concession contract whether held by grant or on lease. If the concessionaire has Cameroonian nationality, he could ask for a land certificate that would provide him full ownership of this land. If the provisional concessionaire is a foreigner, he could obtain an emphyteutic lease that can be renewed or withdrawn in case of non-compliance of some duties, notably the assigned land use.

Although the majority legal opinion concerning carbon ownership in Cameroon is that it will follow the same legal status as other natural resources, i.e., follow the ownership to land, there is no explicit legislation or respective jurisdiction by courts on this matter so that some uncertainty remains. Some authors even argue that a carbon credit could be categorized as an intangible asset [62] and take the form of a monetary asset representing the result of an action. Accordingly, ownership of carbon credits would be granted to forest actors who prove that they are behind the action. This claim would not necessarily “be based on land tenure, but could also include ancestral rights, operating rights, use rights or capital investment” [63] (p. 144).

Taking the current legal framework and majority legal opinion in Cameroon into consideration, it implies that the State as owner or manager of most of the forest land will be the main beneficiary of any carbon rent obtained under future international REDD+ BSM. Furthermore, as the current situation of forest and land management in Cameroon shows, the government has allocated some privileges to concessionaries. Thus, REDD+ proponents or promoters can be expected to be main beneficiaries of a potential carbon rent. Based on experiences from the current policy and practice of RFA redistribution, other stakeholders such as local councils and communities and indigenous people will to a lesser extent be eligible beneficiaries. Therefore, despite the fact that the current land and forest law in Cameroon is very complex and privileges the State as main beneficiary, other stakeholders such as local communities and indigenous people could to a lesser extent generate benefits from a future international REDD+ BSM. It can be expected that under the current legal situation, liability for future carbon losses will rest with the owner of the forest land or the holder of a use right. However, this implies that clarity of land and forest tenure in Cameroon is needed for the functionality of any future national BSM.

4.4. Vietnam

Vietnam is planning to take a “national approach” (see Section 2) to REDD+ benefit sharing where the country as a whole will be rewarded for the reduced emissions through an international finance mechanism under the UNFCCC. According to Decision 799 on the National REDD+ program, the BSM in Vietnam is based on a National REDD Fund, which is established under the Vietnam Forest Protection and Development Fund (VNFF). After years of deliberations on the specific design of the REDD+ Fund, the fund will be set up within existing government structures and established at central level only with no additional funds at the provincial level. The fund will mobilize and receive contributions and grants provided by foreign countries, organizations or individuals for REDD+ activities and voluntary grants from domestic entities [64]. For the domestic disbursement of financial benefits through the REDD+ Fund, the national Payments for Forest Environmental Services Program (PFES) may act as a blue print. PFES already includes carbon ES as one of four ES considered when determining direct and indirect payments to the providers of the services through forest protection activities [65].

The discussion about the definition of carbon rights, who should own them, and who should benefit from them has only recently been taken up, and the government acknowledges that there are gaps in the legal framework [66]. Yet, current forest and related policies offer numerous interpretations on how carbon rights can be defined in Vietnam, and therefore need to be better clarified through the national REDD+ program. According to the Vietnamese Constitution all land and forest resources belong to the people. The state acts as their representative and manages the resources for stable long-term use [67]. According to several donors, such as the UN-REDD Programme, which supports nationally-led REDD+ readiness processes [68], this means that the country as a whole will be rewarded for the reduced emissions and, therefore, there is no need to define individual carbon rights. However, the 2003 Land Law stipulates that “the State shall grant land use rights to land users via the allocation of land, lease of land, and recognition of land use rights for persons currently using the land stably” (Art. 5) and defines in detail the rights to possess, manage and use land. Recognized land users include mass organizations, communities, family households and individuals (Art. 9). These landholders must use their land economically, effectively and in an environmentally protective manner (Art. 11). If landholders comply with Art. 11 they obtain the right to benefit form the results of their labor and the results of investments in the land. Furthermore they may appreciate the benefits arising from state works for protection and improvement of agricultural land and the right to be issued certificates of their land use rights (Art. 105) [69]. Following the reasoning of this law, there is an individual entitlement to benefit streams generated through land-use activities that could be applicable to REDD+ activities. In the specific case of natural forests, the 2004 Forest Protection and Development Law assigns exclusive management and decision-making rights to the state. This includes the right to regulate any benefits and profits generated from natural forest [69]. Similar to the General Land Law “it also grants forest users some managerial rights over the forest, as well as the right to generate income and benefits from their labor and investments in forest land” [66] (p. 16). “In principle, this means that forest owners will have the right to receive the value added from carbon payments from the point where they are allocated land” [66] (p. 27).

The debate on carbon rights is further complicated by recent concerns raised by the domestic private sector, particularly the timber processing and furniture industry. The Forest Protection and Development Law 2004 and the Decree 99 on the National Payment for Forest Environmental Services Law explicitly recognizes the principle that buyers may purchase forest goods and services, delivering payments to those who protect and regenerate the forests. According to Article 84 of the 2005 Law on Environmental Protection, carbon emission transactions with international buyers would have to be approved by the Prime Minister. According to Prime Minister decision No. 1775/QD-TTg on Approval of Project of Greenhouse Gas Emission Management, Management of Carbon Credit Business Activities to the Global Market, international and national organizations, the private sector, legal entities that are involved in developing, implementing and managing REDD+ activities which may lead to the allocation of carbon credits in the voluntary (or later compulsory) carbon market in Vietnam should be encouraged and supported. Following this legal interpretation, the private sector would currently have no ownership rights over forest lands. However, it could obtain rights to benefit from REDD+ activities through officially assigned use rights. Several domestic stakeholders from the private sector that have participated in REDD+ consultation workshops claim that the major incentives for them to get involved in REDD+ projects is to obtain rights to benefit from REDD+ activities [66].

As can be seen from the analysis above, the exact interpretation of carbon rights, especially of who is entitled to benefit streams, is still unclear due to the complexity of current legal documents and the REDD+ framework. The National REDD+ Program 2012 was expected to address that lack of clarity, yet carbon rights are still overlooked in political discussion to date [64]. The National REDD+ program, however, highlights that one of its strategic solutions for REDD+ in the future is to set up a legal framework for carbon rights in the next 5 years. Moreover, the structure of the BSM embedded in current national REDD programs has different implications for carbon rights recognition.

The fact that the government finally decided to install a National REDD+ fund under existing government structures—and that the fund is only established at the national level—implies that carbon rights will belong to the people and managed by the government. Thus, non-state actors will have limited leverage over the distribution of carbon rights. However, personal communication with representatives from MARD and the National REDD+ Fund shows limited discussion and consideration of this issue in the current national REDD+ plan and operational guidelines of the fund. While donors and international nongovernmental organizations (INGOs) seem to support this approach, civil society organizations (CSOs) and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) raise concerns. They fear that local authorities, CSOs and local projects will not have a voice in the process of negotiating REDD+ activities and payments and that the benefits provided to them will be rather limited. This in turn could lead to a lack of motivation for local people to participate in the process and hamper overall effectiveness of the approach. However, even framing carbon rights as linked to forest use rights as indicated in the Land Law and the Forest Protection and Development Law, local people are in a disadvantaged situation concerning the access to and benefits from carbon rights. Currently, the majority of high quality forests (more than 85%—see [66]) are kept and managed by state owned companies, so the main benefits derived from REDD+ activities would be distributed to government agencies. Therefore, the current conceptualization of carbon rights based on existing laws could reaffirm existing inequity without strengthening the legal status of local people.

In Vietnam, as the state manages the land and forest on behalf of its citizens, the state will receive and manage the benefits derived from REDD+ activities for the nation. Thus, it seems likely that the state itself will be held liable if it fails to reduce emissions. Yet, how this will be translated into practice remains unclear. Even though the government is currently developing a national REDD+ safeguards system, the issue of liability is overlooked. Experience from the implementation of the national PFES program shows that the state sub-contracts non-state actors to conduct forest protection activities. In this contract non-state actors may be held accountable in case of not conducting agreed upon patrol and management of the forest. However, these obligations are not always clearly stated and communicated in the formal forest protection agreement between the state agencies and the sub-contractors. The reasons for the lack of clarity amongst others lie in poor contract arrangement and too little communication effort devoted to explain those obligations clearly to forest managers. These issues need to be considered in the future development of national REDD+ liability rules.

4.5. Indonesia

In Indonesia, a number of Ministerial Decrees and local bylaws addressing REDD+ exist, amongst them regulations concerning REDD+ or carbon projects by the Ministry of Forestry [49]. However, guidelines concerning the distribution of REDD+ funds are limited. The REDD+ Task Force, now upgraded to officially become a ministerial level REDD+ Agency, has designed a general framework for a centralized funding mechanism, the Financing REDD+ Instruments in Indonesia (FREDDI). As an element of the framework, the Trust Fund for REDD+ is planned to manage, distribute and mobilize funds through three modalities of REDD+ funding instruments: grants, investments and payments for performance (Table 1).

To date, however, it remains unclear what form the financial mechanism will take beyond this framework and “whether carbon is a nationally owned good which should be regulated by the state” [63] (p. 132). Article 33 of the Indonesian Constitution states that “land, water and natural resources shall be controlled by the state and be used for the greatest benefit of the people”. This statement gives the Government of Indonesia the authority to control, regulate and manage forest lands and natural resources for the purposes of “national welfare” [69]. Currently, 68% of the 187 million hectares of Indonesia’s land mass is administered by the Ministry of Forestry and classified as the forest zone (kawasan hutan). The Ministry has the authority to lease state forest areas within the forest zone to individuals, private companies, cooperatives and state owned enterprises [70].

Issues relating to carbon tenure are covered by several regulations, among others Government Regulation (GR) 6 of 2007, now amended by GR 3 of 2008 on Forest Planning. For provincial and district governments these regulations (GR 6 of 2007 and GR 3 of 2008) provide a key legal basis, authorizing provincial and district governments to issue Permits for the Utilization of Environmental Services called Izin Usaha Pemanfaatan Jasa Lingkungan (IUPJL) [71]. Article 25 in both GR 6 of 2007 and GR 3 of 2008 states that carbon sequestration and storage are among the incorporated eligible environmental services providing activities in Protection Forests, while Article 33 refers to the same activities in Production Forests (GR 6 of 2007; GR 3 of 2008). Therefore, these GRs entitle license holders to rights over carbon sequestration and storage in production and protection forests. Licenses are granted for a term of 30 years and can be extended (Article 29 and 50 of GR 6 of 2007 and GR 3 of 2008, respectively) [72]. As is the case with forest product extraction by concession holders, an IUPJL suggests that “carbon tenure in state forests does not entail right of ownership, instead it is limited to right of enterprise by selling sequestered carbon to third parties” [73] (p. 34).

Further arrangements regarding procedures for securing carbon sequestration and storage permits are provided in the lower level Ministry of Forestry Regulation (MoF-R) 36 of 2009 on Procedures for Licensing of Commercial Use of Carbon Sequestration and/or Storage in Production and Protection Forests. MoF-R 36 of 2009 refers to forest carbon sequestration and storage as part of ES activities in Production and Protection Forests, including a series of activities under sustainable forest management [73]. The regulation provides the opportunity for holders of management rights over production and protection forests, including timber concessionaires and communities, to apply for IUPJL of carbon sequestration and storage. MoF-R 36 of 2009 determines who can finance carbon projects under IUPJL and who will receive payments from the sale of carbon offsets and the proportions to be assigned to each recipient. It provides that specified permit holders can apply, with a fee, for a permit for carbon sequestration and storage activities, for a period of 25 years with the possibility of extension. According to Article 5, this includes those who (1) hold forest timber concessions for natural, plantation or community plantation forests; (2) hold use permits for protection forests or community forests; or (3) are village forest managers. In areas not subject to permits, Article 7 stipulates that individuals, cooperatives and other businesses operating in priority areas of agriculture, estate crops or forestry may also submit proposals for carbon sequestration and storage enterprises [73]. As with other forest product use or extraction permits, business permits regulate the distribution of benefits from carbon sequestration and storage. Annex III of this regulation states that the benefits of sequestration and storage are to be distributed not only to the state (in the form of non-tax state revenue) but also to surrounding communities according to a set of uniform percentage-based splits [69,73].

While some perceive MoF-R 36/2009 as adding clarity to carbon rights in protection and production forests (e.g., [69]), the legal situation is actually ambiguous. First, Article 4 of MoF-R 36 states that the implementation of carbon storage from REDD and carbon sequestration from CDM will be guided by separate MoF-R, which means that MoF-R 36 only applies to IUPJL. Doubts remain as to whether the benefit sharing arrangement guidelines provided by MoF-R 36 of 2009 will ultimately be implemented due to several issues. First, the regulation states that it will be elaborated by another regulation but none has been formulated to date. Second, revenue sharing arrangements are under the responsibility of the Ministry of Finance rather than the Ministry of Forestry. As such the Ministry of Finance challenges the provision [74]. Third, the determination of REDD+ or carbon sequestration and storage revenues as non-tax revenues should be stipulated by a Government Regulation, not by a Ministerial Regulation. A Government Regulation has a higher status than a Ministerial Regulation, thus doubts about the legality of the regulation remain.

A new GR 12 of 2014 on Types and Tariffs of Non-tax Government Revenue in the Ministry Forestry regulates how much of carbon proceeds should be paid to the Government. Article 1 of this regulation sets out that transactions resulting from carbon sequestration and carbon storage from the forest zone are determined as one source of non-tax revenue in the Ministry of Forestry. The appendix of Article 1 sets this tariff to 10% of the sales from transactions associated with carbon sequestration and storage. GR 12 of 2014 provides important insights related to carbon tenure. Although carbon tenure is not described explicitly in any documents, this GR suggests that proceeds from “carbon extraction” are regulated by the state and in this sense treated as analogous to timber or other forest products. The government treats carbon derived from the forest zone as a sale-able commodity and hence imposes a tariff on its sale. In this case, the rights to use of forests allows for a right to sell the carbon. It is important to note that MoF-R 36 of 2009 and GR 12/2014 only regulate carbon within the forest zone. Thus, any transactions of carbon from forests outside the forest zone (some areas outside the Forest Zone are forested) are not regulated under these policies (see also [72]).

Other Ministry of Forestry regulations are also available to provide guidelines for carbon activities. For example, MoF-R 30 of 2009 on the procedures of REDD+ determines the procedures to establish REDD+ projects both in state and rights (non-state) forests. Project proponents have the right to receive payments for emission reductions and to sell carbon from the REDD+ interventions and are obliged to manage forests within REDD+ implementation. MoF-R 20 of 2012 on Forest Carbon Implementation on both demonstration activities and full implementation lays out the rights and responsibilities of carbon project proponents, which include the right to implement carbon-related activities and to sell the carbon managed, and that the government gets levies from the resulting carbon transactions. This regulation does not mention carbon tenure. However, Article 3 of the regulation states that forest carbon implementation is also aimed to empower communities within and outside the forest zone. The regulation thus provides guidelines for both state forests (all categories of the forest zone, production, protection and conservation forests) and rights forests (i.e., non-state forests), including community forests.

Even though a number of state regulations with respect to benefit sharing from carbon emission reduction activities and carbon rights have been enacted in Indonesia in the past decade, fundamental questions about the validity of some of the regulations exist. There seems to be a trend in the regulations treating the provision of forest carbon ES as a land use comparable to other land uses for which use rights can be given out by the state. Furthermore, it seems as if the holder of such a use-right will thereby receive the right to benefit from the provision of these ES. While the regulations cited above all consider some share of the revenues generated to be distributed to the state, the specific percentage varies. For example, the 2014 regulation suggests that the government will only receive 10% of carbon sales—the distribution of the remaining 90% remains unanswered. In addition, the procedures on the reporting of carbon sales have not been formulated.

While those granted the permits for carbon sequestration and storage activities have the right to sell the carbon, as regulated by MoF-R 36 of 2009, the associated obligations and risks are not spelled out in the regulation. It seems that with the transfer of use rights the carbon ES provider also carries liability in case these services are not provided. As a way to hedge for failure of delivery, Article 17 states that the permit holder or project owner can insure the carbon project nationally or internationally. Furthermore, Articles 25 and 33 of GR 3 of 2008 state the obligation that business activity of ES utilization in protected forest (Article 25) or production forest (Article 33) “shall be executed with the provision that the activity does not reduce, change or eliminate the main function thereof, does not change landscape, does not destroy equilibrium of environmental substances”.

Table 1.

Assessment of national carbon rights legislation in focus countries.

| Assessment Steps | Implementation Options | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. National approach to benefit sharing | Domestic incentive based mechanism (e.g. Trust fund or PES) | Carbon market | Nested approach | |||

| Peru | Yes | Yes, some states | Yes | |||

| Brazil | Yes, Amazon Fund at federal level | Not at federal level, but in some states | De facto | |||

| Cameroon | Yes | Unlikely | No | |||

| Vietnam | Yes, REDD+ Funds, PFES | Yes, through national level | No | |||

| Indonesia | Yes | Yes | Specified emissions reductions targets for provincial level | |||

| 2. Legal basis for carbon rights | Explicitly defined? | Implicitly treated as… | ||||

| Peru | Yes, defined for PAs and in new PES law | Natural resource or ‘fruit’, in PES law C-seq as ES | ||||

| Brazil | Not on federal level, but in some state legislations | Natural resources / Environmental Services | ||||

| Cameroon | No | Natural resources | ||||

| Vietnam | No, but recognized in PFES | Forest resources; in PFES Forest goods & services | ||||

| Indonesia | Yes, but disputed | C-seq & storage as ES | ||||

| 3. Carbon rights dimensions | Property | Benefit | Credit | |||

| Peru | Yes | If treated as ‘fruit’, and in PES law | Yes for PAs | |||

| Brazil | Yes | Yes, but also obligation to compensate | Not at the national level, but some state level projects do generate credits at the voluntary market | |||

| Cameroon | Yes | Yes | No | |||

| Vietnam | Yes | Yes | No | |||

| Indonesia | Yes | Yes | No domestic system, but participation of projects in the voluntary market | |||

| 4. Allocation mode | Separate proprietary interest | Tied to resource | Tied to land (use) | |||

| Peru | Yes (in case of PAs) | Yes | Yes | |||

| Brazil | In some states | Yes | Yes | |||

| Cameroon | No | Yes, but linked to land ownership | Yes | |||

| Vietnam | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Indonesia | Yes | Yes | ||||

| 5. Type of property right | Full ownership | Usu fruct | ||||

| Peru | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Brazil | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Cameroon | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Vietnam | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Indonesia | Yes | Yes | ||||

| 6. Rights holder | Nation / state (common property) | Communal (private property) | Individual (private property) | |||

| Peru | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Brazil | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Cameroon | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Vietnam | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| Indonesia | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| 7. Liability | Not explicitly defined in any of the countries, but most likely vested with the property rights holder. In case of transfer of use rights. Agreement between owner and use-rights holder on accountability of use rights holder. | |||||

5. Discussion—Policy Implications

5.1. Status Quo of Carbon Rights

Most of the countries assessed in the previous section have not made final decisions as to the type of BSM they intend to implement under their jurisdiction (Table 1). All countries are focusing on the design and implementation of incentive based benefit sharing mechanisms for the provision of carbon ES. In the process of benefit sharing implementation decisions in domestic law and policy need to be made as to who will be the eligible recipients of these benefits. In Vietnam and, recently, Peru, laws for PES have been passed that define beneficiaries and explicitly include carbon sequestration and storage as ES. Brazil is in the process of establishing a fund-based system at the national level while in some federal states of the Amazon market-based mechanism have already been established. In these processes beneficiaries are being defined. The main challenge this country faces is the “nesting” of activities and payment distribution of the sub-national levels into the national approach to REDD+ [75]. Peru, pursuing a similar approach, faces comparable multi-level governance challenges. In Indonesia, the REDD+ agency is currently considering a trust fund for REDD+ benefit sharing, while the challenged Ministry of Forestry Decrees still exist that allow for project implementers to directly benefit from carbon markets.

Even though the country-level analysis shows that the clarification of carbon rights is perceived as a pressing issue, such legal clarification has progressed slowly. Carbon rights may be unambiguously defined by passing explicit legislations that determine how carbon rights are allocated or by linking them to existing rights to natural resources or ES. Vietnam and Peru have defined carbon rights to varying degrees in their national PES laws. In Indonesia multiple laws and decrees for the provision of the ES carbon sequestration and storage exist, however doubts remain as to the validity and enforceability, with intersectoral tensions surrounding them. Harmonizing and aligning these approaches while at the same time improving clarity on the legality of existing decrees and government regulations poses a major challenge. In Brazil the federal government is constructing a REDD+ National Strategy, and some federal states in the Brazilian Amazon have adopted carbon rights legislation. Meanwhile, Cameroon has not advanced any explicit legal clarification of carbon rights at all. Thus, different ways for institutionalizing carbon rights implicitly by treating rights to carbon as a property similar to existing natural resources or ES, enforced by laws such as the constitution and subsidiary environmental and natural resource laws, are being followed. However, this elusiveness of legal clarity is problematic. Different interpretations of the law lead to competing claims among stakeholders who hold different property rights and use rights over forest and land resources. This can lead to higher transaction costs for REDD+ initiatives, as without legal clarity, project developers must act on a case-by-case basis and ad hoc strategies for allocating rights to benefit streams from carbon. As a result, projects may be less attractive for investors as costs that arise from conflicts over carbon rights may compromise projects’ success [11]. As analysis of early experiences from the voluntary carbon market shows, clear government regulations are need to resolve underlying uncertainties and potential conflicts [10].

Across countries, there is a trend towards linking carbon rights to the land rights. In many of the countries analyzed, the state is either the constitutionally defined owner of forests, or constitutionally mandated to manage forests on behalf of the nation or the people. Given that the state is so commonly the legal owner of forests, management rights must often be conferred through usufruct rights. These usufruct rights tend to take the form of concessions, and they often imply rights to benefit from natural resources and also ES. Since these usufruct rights are common, and are often already allocated widely, it may make sense to align carbon rights with these usufruct rights. However, in this case, attention needs to be paid to avoid overlaps with existing (customary) use right of indigenous and local communities [10].

A subject not tackled in most national strategies to REDD+ is the question of liability in case of failure of delivering emissions reductions. There seems to be an implicit tenor that whoever owns the carbon is responsible for its release into the atmosphere. The owner that transfers use rights can then agree on transferring liability to the use-rights holder.

5.2. Implications

The status quo of carbon rights legislation, wherein complete clarity has been elusive in spite of an emergent trend towards linking carbon rights to various land and ES rights, has several important implications for REDD+ benefit sharing, and especially for local and indigenous communities.

State ownership or management rights pose the threat that local and indigenous communities’ (customary) rights remain unnoticed or become subject of unilateral extinguishment [10]. Sometimes, the government recognizes that land rights are distinct from or in conflict with local customary rights claims. While those with clear legal status under national law will secure the benefits, the situation for customary and indigenous rights holders without land titles is uncertain. These groups are vulnerable and may lose out as they have always struggled to articulate their claims to their customary lands. Frequently, entitlements are not sufficiently recognized under national law, which spurs the concern that traditional or customary land rights will be ignored [49]. In Indonesia for example, even though a legal mechanism to secure tenure rights of forest-dependent communities exists, in practice most communities do not possess legally recognized forest tenure rights. Coupled with poor spatial planning, this may lead to increased marginalization and exploitation of local communities while the government and the private sector will potentially be capturing most benefits [76,77]. Thus, investments in administrative capacities to record and govern the complex tenure arrangements are needed to provide certainty for customary rights holders [10].

Following a usufruct approach to carbon rights poses similar challenges as other forms of resource concessions have in the past. As research on tenure and benefit sharing highlights, there is a high risk of unlawful issuance of use rights, especially in countries with weak governance and high corruption [5,31]. Furthermore, granting carbon rights through use rights may complicate land use management, especially when multiple parties have overlapping use rights [10]. In such cases, actors with a stake in carbon rights specifically may have issues arising from conflict between their interest in preserving standing forest carbon stocks and local communities or other rights-holders’ interest in exploiting natural forest resources including through deforestation and forest degradation [8].

The existing land tenure regimes in the assessed countries are already very complex and subject to multiple and conflicting land uses. Even in cases of clear legislation as is the case in Peru, only careful due diligence can reveal any unregistered or overlapping claims to land on the basis of customary use. Therefore, existing land titling initiatives should be strengthened, since forest land use and the absence of land titles have caused conflict [78], particularly when granting titles of various kinds on the same natural resource or degrees are awarded on various natural resources that are located in the same environment. Thus, existing initiatives for land use rights clarification should be promoted through national REDD+ readiness activities by tying carbon rights to existing rights.

Even in the case of recognized rights to carbon, forest resources, or the land, attention must be paid to overcome inequity in “access” or “context” [79,80]. Maintaining the status quo of land rights distribution may consolidate existing inequalities. In Vietnam for example, more than 85% of high quality forest are managed by state forest enterprises [66], which will most likely result in disproportionately high benefits from REDD+ for these actors. In many cases, local communities who have formal rights over a resource lack the capital to invest in making the resource productive. In this way, merely holding the right to carbon as property and the right to benefit from it may not be sufficient to actually realize benefits. This is especially salient given the transaction costs associated with entry into carbon markets, including setting reference levels, accessing buyers, carrying out monitoring, reporting and verification and securing credit [7]. In this way, a private market would favor large landowners with the financial and technical capacity to cover these transaction costs and actually benefit from REDD+ projects through carbon markets [12]. A state ownership approach in which the state invests the necessary resources to establish a MRV system and keeps a share of the benefits to cover these transaction costs—but passes on most of the compensation for opportunity costs to the carbon rights holders—seems a practical solution. Another option is strengthening the role of NGOs acting as facilitating intermediaries between buyers and local and indigenous communities as providers of carbon ES.

6. Conclusions