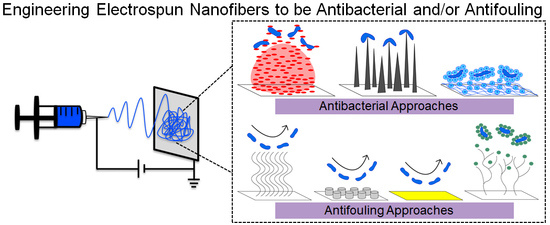

Current and Emerging Approaches to Engineer Antibacterial and Antifouling Electrospun Nanofibers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Brief Background on the Electrospinning Process and General Strategies to Tailor Antibacterial and Antifouling Nanofiber Mats

3. Established and Emerging Approaches to Engineering Antibacterial and Antifouling Surfaces and Nanofiber Mats

3.1. General Approaches to Engineering Antibacterial Surfaces

3.2. Specific Examples of Antibacterial Nanofiber Mats

3.3. General Approaches to Engineering Antifouling Surfaces

3.4. Commonly Selected Polymers for Antifouling Nanofiber Mats

3.5. Specific Examples of Antifouling Nanofiber Mats

4. Perspective and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Costerton, J.W.; Stewart, P.S.; Greenberg, E.P. Bacterial biofilms: A common cause of persistent infections. Science 1999, 284, 1318–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callow, J.A.; Callow, M.E. Trends in the development of environmentally friendly fouling-resistant marine coatings. Nat. Commun. 2011, 2, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, C.X.; Zhang, D.R.; He, Y.; Zhao, X.S.; Bai, R. Modification of membrane surface for anti-biofouling performance: Effect of anti-adhesion and anti-bacteria approaches. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 346, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callow, M.E.; Callow, J.A. Marine biofouling: A sticky problem. Biologist 2002, 49, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Hasan, J.; Crawford, R.J.; Ivanova, E.P. Antibacterial surfaces: The quest for a new generation of biomaterials. Trends Biotechnol. 2013, 31, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, J. Antimicrobial Resistance: Tackling a Crisis for the Health and Wealth of Nations; The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2013; CS239559-B; Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services: Washington, DC, USA, 2013.

- Davies, J.; Davies, D. Origins and evolution of antibiotic resistance. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2010, 74, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crofts, T.S.; Wang, B.; Spivak, A.; Gianoulis, T.A.; Forsberg, K.J.; Gibson, M.K.; Johnsky, L.A.; Broomall, S.M.; Rosenzweig, C.N.; Skowronski, E.W.; et al. Shared strategies for β-lactam catabolism in the soil microbiome. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2018, 14, 556–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO; WIPO; WTO. Antimicrobial Resistance—A Global Epidemic; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, H.; Uehara, T.; Bernhardt, T.G. Beta-Lactam antibiotics induce a lethal malfunctioning of the bacterial cell wall synthesis machinery. Cell 2014, 159, 1310–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engel, Y.; Schiffman, J.D.; Goddard, J.M.; Rotello, V.M. Nanomanufacturing of biomaterials. Mater. Today 2012, 15, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E.D.; Wright, G.D. Antibacterial drug discovery in the resistance era. Nature 2016, 529, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silver, L.L. Multi-targeting by monotherapeutic antibacterials. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007, 6, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Game, F.L.; Hinchliffe, R.J.; Apelqvist, J.; Armstong, D.G.; Bakker, K.; Hartemann, A.; Londahl, M.; Price, P.E.; Jeffcoate, W.J. A systematic review of interventions to enhance the healing of chronic ulcers of the foot in diabetes. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2012, 28, 119–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wilgus, T.A. Immune Cells in the healing skin wound: Influential players at each stage of repair. Pharmacol. Res. 2008, 58, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peppas, N.A.; Keys, K.B.; Torres-Lugo, M.; Lowman, A.M. Poly(ethylene glycol)-containing hydrogels in drug delivery. J. Control. Release 1999, 62, 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arisoy, F.D.; Kolewe, K.W.; Homyak, B.; Kurtz, I.S.; Schiffman, J.D.; Watkins, J.J. Bioinspired photocatalytic shark skin surfaces with antibacterial and antifouling activity via nanoimprint lithography. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 2005–20063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, I.; Pangule, R.C.; Kane, R.S. Antifouling coatings: Recent developments in the design of surfaces that prevent fouling by proteins, bacteria, and marine organisms. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 690–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Yong, K. Combining the lotus leaf effect with artificial photosynthesis: Regeneration of underwater superhydrophobicity of hierarchical ZnO/Si surfaces by solar water splitting. NPG Asia Mater. 2015, 7, e201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magin, C.M.; Cooper, S.P.; Brennan, A.B. Non-toxic antifouling strategies. Mater. Today 2010, 13, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, W. De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de Magno Magnete Tellure; Peter Short: London, UK, 1628. [Google Scholar]

- Larmor, J. Note on the complete scheme of electrodynamic equations of a moving material medium and on electrostricton. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1898, 63, 365–372. [Google Scholar]

- Cooley, J.F. Apparatus for Electrically Dispersing Fluids. U.S. Patent No. 692,631, 4 Feburary 1902. [Google Scholar]

- Morton, W.J. Method of Dispersing Fluids. U.S. Patent 705,691, 29 July 1902. [Google Scholar]

- Formhals, A. Method and Apparatus for the Production of Fibers. U.S. Patent 2,123,992, 19 July 1938. [Google Scholar]

- Formhals, A. Method and Apparatus for the Production of Artificial Fibers. U.S. Patent 2,158,416, 16 May 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Formhals, A. Method and Apparatus for Spinning. U.S. Patent 2,160,962, 6 June 1939. [Google Scholar]

- Persano, L.; Camposeo, A.; Tekmen, C.; Pisignano, D. Industrial upscaling of electrospinning and applications of polymer nanofibers: A review. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2013, 298, 504–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, W.E.; Ramakrishna, S. A review on electrospinning design and nanofibre assemblies. Nanotechnology 2006, 17, R89–R106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.-M.; Zhang, Y.-Z.; Kotaki, M.; Ramakrishna, S. A review on polymer nanofibers by electrospinning and their applications in nanocomposites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2003, 63, 2223–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G. The force exerted by an electric field on a long cylindrical conductor. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 1966, 291, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, G. Electrically driven jets. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 1969, 313, 453–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Hohman, M.; Brenner, M.P.; Rutledge, G. Experimental characterization of electrospinning: The electrically forced jet and instabilities. Polymer 2001, 42, 09955–09967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Perry, S.L.; Schiffman, J.D. Complex coacervation: Chemically stable fibers electrospun from aqueous polyelectrolyte solutions. ACS Macro Lett. 2017, 6, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieger, K.A.; Schiffman, J.D. Electrospinning an essential oil: Cinnamaldehyde enhances the antimicrobial efficacy of chitosan/poly(ethylene oxide) Nanofibers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 113, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casper, C.L.; Yamaguchi, N.; Kiick, K.L.; Rabolt, J.F. Functionalizing electrospun fibers with biologically relevant macromolecules. Biomacromolecules 2005, 6, 1998–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojha, S.S.; Stevens, D.R.; Hoffman, T.J.; Stano, K.; Klossner, R.; Scott, M.C.; Krause, W.; Clarke, L.I.; Gorga, R.E. Fabrication and characterization of electrospun chitosan nanofibers formed via templating with polyethylene oxide. Biomacromolecules 2008, 9, 2523–2529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deitzel, J.M.; Kleinmeyer, J.D.; Hirvonen, J.K.; Tan, N.C.B. Controlled deposition of electrospun poly(ethylene oxide) fibers. Polymer 2001, 42, 8163–8170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobosz, K.M.; Kuo-Leblanc, C.A.; Martin, T.J.; Schiffman, J.D. Ultrafiltration membranes enhanced with electrospun nanofibers exhibit improved flux and fouling resistance. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017, 56, 5724–5733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repanas, A.; Andriopoulou, S.; Glasmacher, B. The significance of electrospinning as a method to create fibrous scaffolds for biomedical engineering and drug delivery applications. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2016, 31, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenawy, E.R.; Bowlin, G.L.; Mansfield, K.; Layman, J.; Simpson, D.G.; Sanders, E.H.; Wnek, G.E. Release of tetracycline hydrochloride from electrospun poly(ethylene-co-vinylacetate), poly(lactic acid), and a blend. J. Control. Release 2002, 81, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Su, Q.; Liu, W.; Jin, G.; Mo, X.; Ramakrishn, S. Dual-drug encapsulation and release from core–shell nanofibers. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2012, 23, 861–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiffman, J.D.; Elimelech, M. Antibacterial activity of electrospun polymer mats with incorporated narrow diameter single-walled carbon nanotubes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenawy, E.-R.; Abdel-Hay, F.I.; El-Newehy, M.H.; Wnek, G.E. Processing of polymer nanofibers through electrospinning as drug delivery systems. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2009, 113, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suwantong, O.; Opanasopit, P.; Ruktanonchai, U.; Supaphol, P. Electrospun cellulose acetate fiber mats containing curcumin and release characteristic of the herbal substance. Polymer 2007, 48, 7546–7557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charernsriwilaiwat, N.; Opanasopit, P.; Rojanarata, T.; Ngawhirunpat, T. Lysozyme-loaded, electrospun chitosan-based nanofiber mats for wound healing. Int. J. Pharaceutics 2012, 427, 379–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalf, A.; Madihally, S.V. Recent advances in multiaxial electrospinning for drug delivery. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2017, 112, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.S.; Choi, S.H.; Yoo, H.S. Coaxial Electrospun nanofibers for treatment of diabetic ulcers with binary release of multiple growth factors. J. Mater. Chem. 2011, 21, 5258–5267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Hu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhao, P.; Zhu, K.; Chen, W. A facile technique to prepare biodegradable coaxial electrospun nanofibers for controlled release of bioactive agents. J. Control. Release 2005, 108, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.-J.; Wang, C.-Y.; Wang, J.-G.; Ruan, H.-J.; Fan, C.-Y. Peripheral nerve regeneration using composite poly(lactic acid-caprolactone)/nerve growth factor conduits prepared by coaxial electrospinning. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2011, 96, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pakravan, M.; Heuzey, M.-C.; Ajji, A. Core–shell structured PEO-chitosan nanofibers by coaxial electrospinning. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 412–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.T.T.; Chung, O.H.; Park, J.S. Coaxial electrospun poly(lactic acid)/chitosan (core/shell) composite nanofibers and their antibacterial activity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 86, 1799–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Hu, P.; Xu, J.; Wang, A.; Wang, A. Encapsulation of drug reservoirs in fibers by emulsion electrospinning: Morphology characterization and preliminary release assessment. Biomacromolecules 2006, 7, 2327–2330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Y.; Zhang, L.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, Z.-T.; Fong, H. Preparation, characterization, and encapsulation/release studies of a composite nanofiber mat electrospun from an emulsion containing poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid). Polymer 2008, 49, 5294–5299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Yang, L.; Xu, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Liang, Q.; Zeng, J.; Jing, X. Ultrafine medicated fibers electrospun from w/o emulsions. J. Control. Release 2005, 108, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Li, X.; Cui, W.; Zhou, S.; Tan, R.; Wang, C. Structural stability and release profiles of proteins from core-shell poly(dl-lactide) ultrafine fibers prepared by emulsion electrospinning. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2008, 86, 374–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Zhuang, X.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Yang, L.; Jing, X. Preparation of core-sheath composite nanofibers by emulsion electrospinning. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2006, 27, 1637–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffman, J.D.; Wang, Y.; Giannelis, E.P.; Elimelech, M. Biocidal activity of plasma modified electrospun polysulfone mats functionalized with polyethyleneimine-capped silver nanoparticles. Langmuir 2011, 27, 13159–13164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.S.; Yoo, H.S. MMPs-Responsive release of DNA from electrospun nanofibrous matrix for local gene therapy: In vitro and in vivo evaluation. J. Control. Release 2010, 145, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, Y.I.; Park, B.J.; Kim, H.-L.; Lee, M.H.; Kim, J.; Yang, Y.-I.; Kim, J.K.; Tsubaki, K.; Han, D.-W.; Park, J.-C. The biological activities of (1,3)-(1,6)-β-d-glucan and porous electrospun PLGA membranes containing β-glucan in human dermal fibroblasts and adipose tissue-derived stem cells. Biomed. Mater. 2010, 5, 044109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.S.; Leong, K.W.; Yoo, H.S. In vivo wound healing of diabetic ulcers using electrospun nanofibers immobilized with human epidermal growth factor (EGF). Biomaterials 2008, 29, 587–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieger, K.A.; Porter, M.; Schiffman, J.D. Polyelectrolyte-functionalized nanofiber mats control the collection and inactivation of Escherichia coli. Materials 2016, 9, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.O.; Yoon, I.S.; Lee, S.Y.; Kim, D.D.; Lee, S.J.; Park, W.H.; Hudson, S.M. Chitosan-coated poly(vinyl alcohol) nanofibers for wound dressings. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2010, 92, 568–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spasova, M.; Paneva, D.; Manolova, N.; Radenkov, P.; Rashkov, I. Electrospun chitosan-coated fibers of poly(L-lactide) and poly(L-lactide)/poly(ethylene glycol): Preparation and characterization. Macromol. Biosci. 2008, 8, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Bromberg, L.; Lee, J.A.; Zhang, H.; Schreuder-Gibson, H.; Gibson, P.; Walker, J.; Hammond, P.T.; Hatton, T.A.; Rutledge, G.C. Multifunctional electrospun fabrics via layer-by-layer electrostatic assembly for chemical and biological protection. Chem. Mater. 2010, 22, 1429–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieger, K.A.; Birch, N.P.; Schiffman, J.D. Designing electrospun nanofiber mats to promote wound healing—A review. J. Mater. Chem. B 2013, 1, 4531–4541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, G.A.; Swogger, E.; Wolcott, R.; Pulcini, E.d.; Secor, P.; Sestrich, J.; Costerton, J.W.; Stewart, P.S. Biofilms in chronic wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 2008, 16, 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention. National Diabetes Fact Sheet, 2011; Center for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2011; pp. 1–12.

- He, J.H.; Wan, Y.Q.; Xu, L. Nano-effects, quantum-like properties in electrospun nanofibers. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2007, 33, 26–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goyal, R.; Macri, L.K.; Kaplan, H.M.; Kohn, J. Nanoparticles and nanofibers for topical drug delivery. J. Control. Release 2016, 240, 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- GhavamiNejad, A.; Rajan Unnithan, A.; Ramachandra Kurup Sasikala, A.; Samarikhalaj, M.; Thomas, R.G.; Jeong, Y.Y.; Nasseri, S.; Murugesan, P.; Wu, D.; Hee Park, C.; et al. Mussel-inspired electrospun nanofibers functionalized with size-controlled silver nanoparticles for wound dressing application. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 12176–12183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ignatova, M.; Markova, N.; Manolova, N.; Rashkov, I. Antibacterial and antimycotic activity of a cross-linked electrospun poly(vinyl pyrrolidone)-iodine complex and a poly(ethylene oxide)/poly(vinyl pyrrolidone)-iodine complex. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2008, 19, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Chwee, T.L.; Ramakrishna, S.; Huang, Z.M. Recent development of polymer nanofibers for biomedical and biotechnological applications. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2005, 16, 933–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Truong, Y.B.; Zhu, Y.; Louis Kyratzis, I. Electrospun antibacterial nanofibers: Production, activity, and in vivo applications. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2014, 131, 9041–9053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayaci, F.; Umu, O.C.O.; Tekinay, T.; Uyar, T. Antibacterial electrospun poly(lactic acid) (PLA) nano fibrous webs incorporating triclosan/cyclodextrin inclusion complexes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 3901–3908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, K.H.; Huh, M.W.; Meng, W.; Yuan, J.; Hyun, S.H.; Bae, J.S.; Hudson, S.M.; Kang, I.K. Preparation and antibacterial activity of PET/chitosan nanofibrous mats using an electrospinning technique. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2007, 105, 2816–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriegel, C.; Kit, K.M.; Mcclements, D.J.; Weiss, J. Electrospinning of chitosan–poly (ethylene oxide) blend nanofibers in the presence of micellar surfactant solutions. Polymer 2009, 50, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatova, M.; Manolova, N.; Markova, N.; Rashkov, I. Electrospun non-woven nanofibrous hybrid mats based on chitosan and PLA for wound-dressing applications. Macromol. Biosci. 2009, 9, 102–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, K.S.; Yang, C.H.; Huang, S.L.; Chen, C.Y.; Lu, Y.Y.; Lin, Y.S. Recent advances in antimicrobial polymers: A mini-review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takenaka, S.; Tonoki, T.; Taira, K.; Murakami, S.; Aoki, K. Adaptation of Pseudomonas sp. strain 7-6 to quaternary ammonium compounds and their degradation via dual pathways. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007, 73, 1797–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, N.; Berton, P.; Moraes, C.; Rogers, R.D.; Tufenkji, N. Nanodarts, nanoblades, and nanospikes: Mechano-bactericidal nanostructures and where to find them. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 252, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.; Pinault, M.; Pfefferle, L.D.; Elimelech, M. Single-walled carbon nanotubes exhibit strong antimicrobial activity. Langmuir 2007, 23, 8670–8673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pogodin, S.; Hasan, J.; Baulin, V.A.; Webb, H.K.; Truong, V.K.; Nguyen, H.P.; Boshkovikj, V.; Fluke, C.J.; Watson, G.S.; Watson, J.A.; et al. Biophysical model of bacterial cell interactions with nanopatterned cicada wing surfaces. Biophys. J. 2013, 104, 835–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanova, E.P.; Hasan, J.; Webb, H.K.; Truong, V.K.; Watson, G.S.; Watson, J.A.; Baulin, V.A.; Pogodin, S.; Wang, J.Y.; Tobin, M.J.; et al. Natural bactericidal surfaces: Mechanical rupture of Pseudomonas aeruginosa cells by cicada wings. Small 2012, 8, 2489–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanova, E.P.; Hasan, J.; Webb, H.K.; Gervinskas, G.; Juodkazis, S.; Truong, V.K.; Wu, A.H.F.; Lamb, R.N.; Baulin, V.A.; Watson, G.S.; et al. Bactericidal activity of black silicon. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ko, F.; Gogotsi, Y.; Ali, A.; Naguib, N.; Ye, H.; Yang, G.; Li, C.; Willis, P. Electrospinning of continuous carbon nanotube-filled nanofiber yarns. Adv. Mater. 2003, 15, 1161–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salalha, W.; Dror, Y.; Khalfin, R.L.; Cohen, Y.; Yarin, A.L.; Zussman, E. Single-walled carbon nanotubes embedded in oriented polymeric nanofibers by electrospinning. Langmuir 2004, 20, 9852–9855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, M.; Jing, J.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Wu, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Lee, M. Polyoxometalate-driven self-assembly of short peptides into multivalent nanofibers with enhanced antibacterial activity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 2592–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jennings, M.C.; Minbiole, K.P.C.; Wuest, W.M. Quaternary ammonium compounds: An antimicrobial mainstay and platform for innovation to address bacterial resistance. ACS Infect. Dis. 2016, 1, 288–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmona-Ribeiro, A.M.; de Melo Carrasco, L.D. Cationic antimicrobial polymers and their assemblies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 9906–9946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Huang, Z.; Tang, X.; Zhang, X. Antimicrobial cationic polymers: From structural design to functional control. Polym. J. 2018, 50, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, I.M.; Valerie, S.; Wulf, S.; Kornelia, A.; Jechalke, S.S.; Mulder, I.; Siemens, Á.J.; Sentek, V.; Amelung, Á.W.; Smalla, K.; et al. Quaternary ammonium compounds in soil: Implications for antibiotic resistance development. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2018, 17, 159–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, A.-M.; Hershey, R.; Ali, S.; Goel, V. Bactericidal efficacy of electrospun pure and Fe-doped titania nanofibers. J. Mater. Res. 2010, 25, 1761–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Si, S.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, T.; Fan, H.; Yao, Y.; Zhang, Q. Electrospun in-situ hybrid polyurethane/nano-TiO2 as wound dressings. Fibers Polym. 2011, 12, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amna, T.; Hassan, M.S.; Barakat, N.A.M.; Pandeya, D.R.; Hong, S.T.; Khil, M.S.; Kim, H.Y. Antibacterial activity and interaction mechanism of electrospun zinc-doped titania nanofibers. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012, 93, 743–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penchev, H.; Paneva, D.; Manolova, N.; Rashkov, I. Electrospun hybrid nanofibers based on chitosan or N-carboxyethylchitosan and silver nanoparticles. Macromol. Biosci. 2009, 9, 884–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rujitanaroj, P.; Pimpha, N.; Supaphol, P. Wound-dressing materials with antibacterial activity from electrospun gelatin fiber mats containing silver nanoparticles. Polymer 2008, 49, 4723–4732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Song, H.Y.; Lee, B.T. Nano Ag Loaded PVA nano-fibrous mats for skin applications. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B Appl. Biomater. 2011, 96, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakshman, L.R.; Shalumon, K.T.; Nair, S.V.; Jayakumar, R. Preparation of silver nanoparticles incorporated electrospun polyurethane nano-fibrous mat for wound dressing preparation of silver nanoparticles incorporated electrospun polyurethane nano-fibrous mat for wound dressing. J. Macromol. Sci. Part A 2010, 47, 1012–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, W.K.; Youk, J.H.; Park, W.H. Antimicrobial cellulose acetate nanofibers containing silver nanoparticles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2006, 65, 430–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Wu, D.; Qi, S.; Wu, Z.; Yang, X.; Jin, R. Preparation of ultra-fine polyimide fibers containing silver nanoparticles via in situ technique. Mater. Lett. 2007, 61, 4027–4030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rieger, K.A.; Cho, H.J.; Yeung, H.F.; Fan, W.; Schiffman, J.D. Antimicrobial activity of silver ions released from zeolites immobilized on cellulose nanofiber mats. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 3032–3040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demirci, S.; Ustaoǧlu, Z.; Yilmazer, G.A.; Sahin, F.; Baç, N. Antimicrobial properties of zeolite-x and zeolite-a ion-exchanged with silver, copper, and zinc against a broad range of microorganisms. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2014, 172, 1652–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Giner, S.; Torres, A.; Ferrándiz, M.; Fombuena, V.; Balart, R. Antimicrobial activity of metal cation-exchanged zeolites and their evaluation on injection-molded pieces of bio-based high-density polyethylene. J. Food Saf. 2017, 37, e12348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neidrauer, M.; Ercan, U.K.; Bhattacharyya, A.; Samuels, J.; Sedlak, J.; Trikha, R.; Barbee, K.A.; Weingarten, M.S.; Joshi, S.G. Antimicrobial efficacy and wound-healing property of a topical ointment containing nitric-oxide-loaded zeolites. J. Med. Microbiol. 2014, 63, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redfern, J.; Goldyn, K.; Verran, J.; Retoux, R.; Tosheva, L.; Mintova, S. Application of Cu-FAU Nanozeolites for decontamination of surfaces soiled with the ESKAPE pathogens. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2017, 253, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.B.; Peng, C.; Luo, W.J.; Lv, M.; Li, X.M.; Li, D.; Huang, Q.; Fan, C.H. Graphene-based antibacterial paper. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 4317–4323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.; Mauter, M.S.; Elimelech, M. Microbial cytotoxicity of carbon-based nanomaterials: Implications for river water and wastewater effluent. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 2648–2653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lyon, D.Y.; Alvarez, P.J.J. Fullerene Water Suspension (NC60) Exerts antibacterial effects via ros-independent protein oxidation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 8127–8132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Wei, L.; Hao, L.; Fang, N.; Chang, M.W.; Xu, R.; Yang, Y.; Chen, Y. Sharper and faster “nano darts” kill more bacteria: A study of antibacterial activity of individually dispersed pristine single-walled carbon nanotube. ACS Nano 2009, 3, 3891–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Faria, A.F.; Perreault, F.; Shaulsky, E.; Arias Chavez, L.H.; Elimelech, M. Antimicrobial electrospun biopolymer nanofiber mats functionalized with graphene oxide-silver nanocomposites. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 12751–12759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Chen, T.X.; Branford-White, C.J.; Zhu, L.M. Electrospun shikonin-loaded PCL/PTMC composite fiber mats with potential biomedical applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2009, 382, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kontogiannopoulos, K.N.; Assimopoulou, A.N.; Tsivintzelis, I.; Panayiotou, C.; Papageorgiou, V.P. Electrospun fiber mats containing shikonin and derivatives with potential biomedical applications. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 409, 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Said, S.S.; El-Halfawy, O.M.; El-Gowelli, H.M.; Aloufy, A.K.; Boraei, N.A.; El-Khordagui, L.K. Bioburden-responsive antimicrobial PLGA ultrafine fibers for wound healing. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2012, 80, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miao, J.; Pangule, R.C.; Paskaleva, E.E.; Hwang, E.E.; Kane, R.S.; Linhardt, R.J.; Dordick, J.S. Lysostaphin-functionalized cellulose fibers with antistaphylococcal activity for wound healing applications. Biomaterials 2011, 32, 9557–9567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zodrow, K.R.; Schiffman, J.D.; Elimelech, M. Biodegradable Polymer (PLGA) coatings featuring cinnamaldehyde and carvacrol mitigate biofilm formation. Langmuir 2012, 28, 13993–13999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieger, K.A.; Birch, N.P.; Schiffman, J.D. Electrospinning chitosan/poly(ethylene oxide) solutions with essential oils: Correlating solution rheology to nanofiber formation. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 139, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.; Ronca, S.; Mele, E. Electrospun nanofibres containing antimicrobial plant extracts. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarhan, W.A.; Azzazy, H.M.E.; El-Sherbiny, I.M. Honey/chitosan nanofiber wound dressing enriched with allium sativum and cleome droserifolia: Enhanced antimicrobial and wound healing activity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 6379–6390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobosz, K.M.; Kolewe, K.W.; Schiffman, J.D. Green materials science and engineering reduces biofouling: Approaches for medical and membrane-based technologies. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perera-Costa, D.; Bruque, J.M.; González-Martín, M.L.; Gómez-García, A.C.; Vadillo-Rodríguez, V. Studying the influence of surface topography on bacterial adhesion using spatially organized microtopographic surface Patterns. Langmuir 2014, 30, 4633–4641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kargar, M.; Wang, J.; Nain, A.S.; Behkam, B. Controlling bacterial adhesion to surfaces using topographical cues: A study of the interaction of Pseudomonas aeruginosa with nanofiber-textured Surfaces. Soft Matter 2012, 8, 10254–10259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katti, D.S.; Robinson, K.W.; Ko, F.K.; Laurencin, C.T. Bioresorbable nanofiber-based systems for wound healing and drug delivery: Optimization of fabrication parameters. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 2004, 70B, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teo, W.E.; Ramakrishna, S. Electrospun Nanofibers as a platform for multifunctional, hierarchically organized nanocomposite. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2009, 69, 1804–1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurtner, G.; Werner, S.; Barrandon, Y.; Longaker, M. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature 2008, 453, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shai, A.; Maibach, H.I. Wound Healing and Ulcers of the Skin: Diagnosis and Therapy—The practical Approach; Philipp, M., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; Volume 53. [Google Scholar]

- Baum, C.L.; Arpey, C.J. Normal cutaneous wound healing: Clinical correlation with cellular and molecular events. Dermatol. Surg. 2005, 31, 674–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hucknall, A.; Rangarajan, S.; Chilkoti, A. In Ppursuit of zero: Polymer brushes that resist the adsorption of proteins. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21, 2441–2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.H.; Fridrikh, S.V.; Rutledge, G.C. The role of elasticity in the formation of electrospun fibers. Polymer 2006, 47, 4789–4797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorens, E.; Ibañez, H.; del Valle, L.J.; Puiggalí, J. Biocompatibility and drug release behavior of scaffolds prepared by coaxial electrospinning of poly(butylene succinate) and polyethylene glycol. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2015, 49, 472–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, S.; Ni, P.; Wang, B.; Chu, B.; Peng, J.; Zheng, L.; Zhao, X.; Luo, F.; Wei, Y.; Qian, Z. In vivo biocompatibility and osteogenesis of electrospun poly(ε-caprolactone)–poly(ethylene glycol)–poly(ε-caprolactone)/nano-hydroxyapatite composite scaffold. Biomaterials 2012, 33, 8363–8371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmlin, R.E.; Chen, X.; Chapman, R.G.; Takayama, S.; Whitesides, G.M. Zwitterionic SAMs that resist nonspecific adsorption of protein from aqueous buffer. Langmuir 2001, 17, 2841–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, R.S.; Deschatelets, P.; Whitesides, G.M. Kosmotropes form the basis of protein-resistant surfaces. Langmuir 2003, 19, 2388–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Li, L.; Zhao, C.; Zheng, J. Surface hydration: Principles and applications toward low-fouling/nonfouling biomaterials. Polymer 2010, 51, 5283–5293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.L.; Jin, T.W.; Han, Y.M.; Shen, C.H.; Li, Q.; Lin, Q.K.; Chen, H. Bio-inspired terpolymers containing dopamine, cations and MPC: A versatile platform to construct a recycle antibacterial and antifouling surface. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 5501–5510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hower, J.C.; Bernards, M.T.; Chen, S.; Tsao, H.K.; Sheng, Y.J.; Jiang, S. Hydration of “nonfouling” functional groups. J. Phys. Chem. B 2009, 113, 197–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, A.; Jiang, S. Local and Bulk Hydration of zwitterionic glycine and its analogues through molecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 2011, 115, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evers, L.H.; Bhavsar, D.; Mailänder, P. The biology of burn injury. Exp. Dermatol. 2010, 19, 777–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cho, Y.; Cho, D.; Park, J.H.; Frey, M.W.; Ober, C.K.; Joo, Y.L. Preparation and characterization of amphiphilic triblock terpolymer-based nanofibers as antifouling biomaterials. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 1606–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tegoulia, V.A.; Rao, W.; Kalambur, A.T.; Rabolt, J.F.; Cooper, S.L. Surface properties, fibrinogen adsorption, and cellular interactions of a novel phosphorylcholine-containing self-assembled monolayer on gold. Langmuir 2001, 17, 4396–4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, J.; Messersmith, P.B. Universal surface-initiated polymerization of antifouling zwitterionic brushes using a mussel-mimetic peptide initiator. Langmuir 2012, 28, 7258–7266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, R.H.; Hunley, M.T.; Allen, M.H.; Long, T.E. Electrospinning zwitterion-containing nanoscale acrylic fibers. Polymer 2009, 50, 4781–4787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalani, R.; Liu, L. Synthesis, Characterization, and electrospinning of zwitterionic poly(sulfobetaine methacrylate). Polymer 2011, 52, 5344–5354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerick, E.; Grant, S.; Bernards, M. Electrospinning of sulfobetaine methacrylate nanofibers. Chem. Eng. Process Technol. 2013, 1003, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Lalani, R.; Liu, L. Electrospun zwitterionic poly(sulfobetaine methacrylate) for nonadherent, superabsorbent, and antimicrobial wound dressing applications. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 1853–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, S.H.; Hong, Y.; Sakaguchi, H.; Shankarraman, V.; Luketich, S.K.; DAmore, A.; Wagner, W.R. Nonthrombogenic, biodegradable elastomeric polyurethanes with variable sulfobetaine content. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 22796–22806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Govinna, N.; Kaner, P.; Ceasar, D.; Dhungana, A.; Moers, C.; Son, K.; Asatekin, A.; Cebe, P. Electrospun fiber membranes from blends of poly(vinylidene fluoride) with fouling-resistant zwitterionic copolymers. Polym. Int. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, S.; Kaner, P.; Thomas, D.; Cebe, P.; Asatekin, A. Hydrophobic anti-fouling electrospun mats from zwitterionic amphiphilic copolymers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 18300–18309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolewe, K.W.; Dobosz, K.M.; Rieger, K.A.; Chang, C.C.; Emrick, T.; Schiffman, J.D. Antifouling electrospun nanofiber mats functionalized with polymer zwitterions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 27585–27593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, C.J.; Stoyanov, S.D.; Stride, E.; Pelan, E.; Edirisinghe, M. Electrospinning versus fibre production methods: From specifics to technological convergence. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 4708–4735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anselme, K.; Davidson, P.; Popa, A.M.; Giazzon, M.; Liley, M.; Ploux, L. The interaction of cells and bacteria with surfaces structured at the nanometre scale. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 3824–3846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kurtz, I.S.; Schiffman, J.D. Current and Emerging Approaches to Engineer Antibacterial and Antifouling Electrospun Nanofibers. Materials 2018, 11, 1059. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11071059

Kurtz IS, Schiffman JD. Current and Emerging Approaches to Engineer Antibacterial and Antifouling Electrospun Nanofibers. Materials. 2018; 11(7):1059. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11071059

Chicago/Turabian StyleKurtz, Irene S., and Jessica D. Schiffman. 2018. "Current and Emerging Approaches to Engineer Antibacterial and Antifouling Electrospun Nanofibers" Materials 11, no. 7: 1059. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11071059