Au3+/Au0 Supported on Chromium(III) Terephthalate Metal Organic Framework (MIL-101) as an Efficient Heterogeneous Catalystfor Three-Component Coupling Synthesis of Propargylamines

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

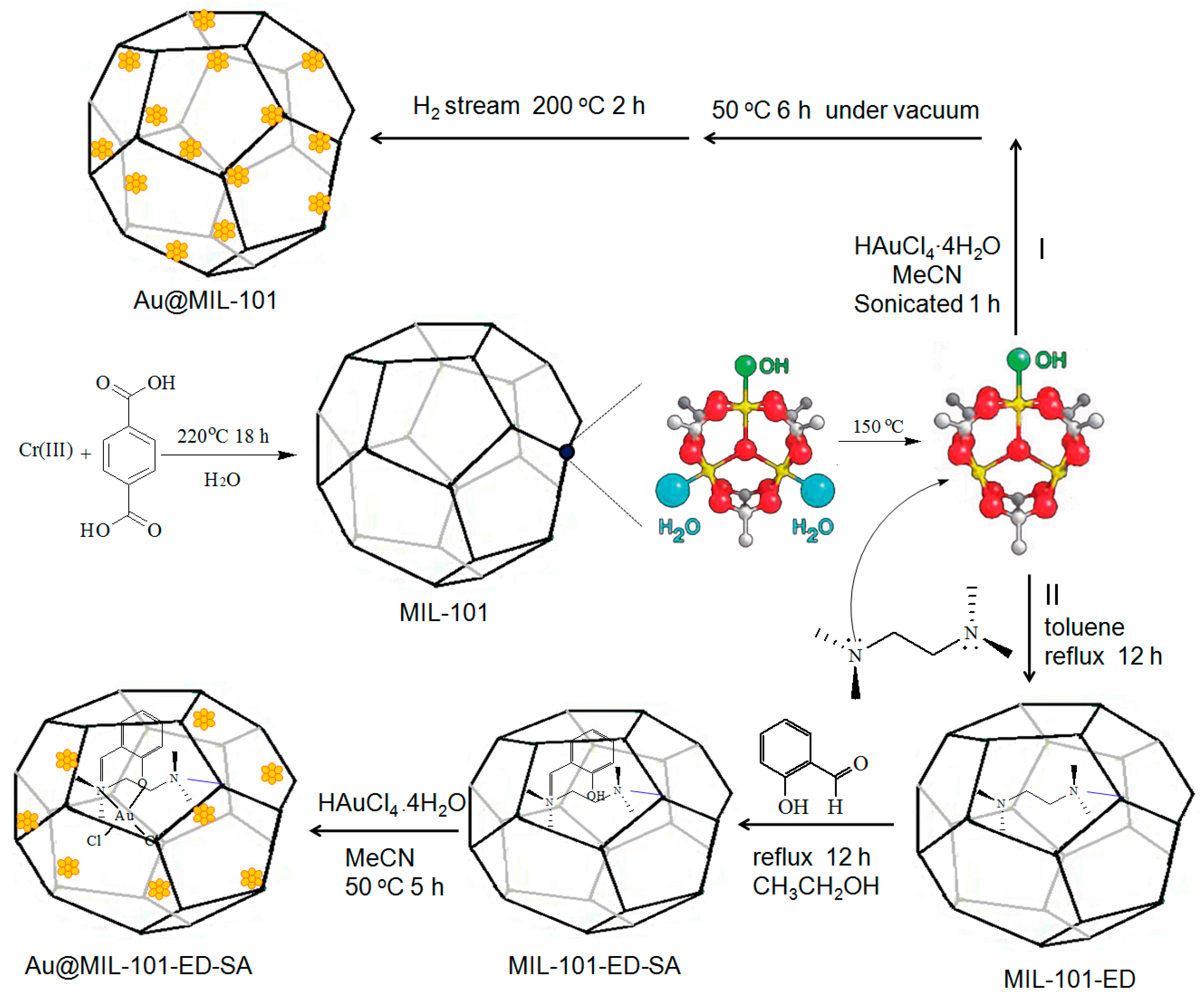

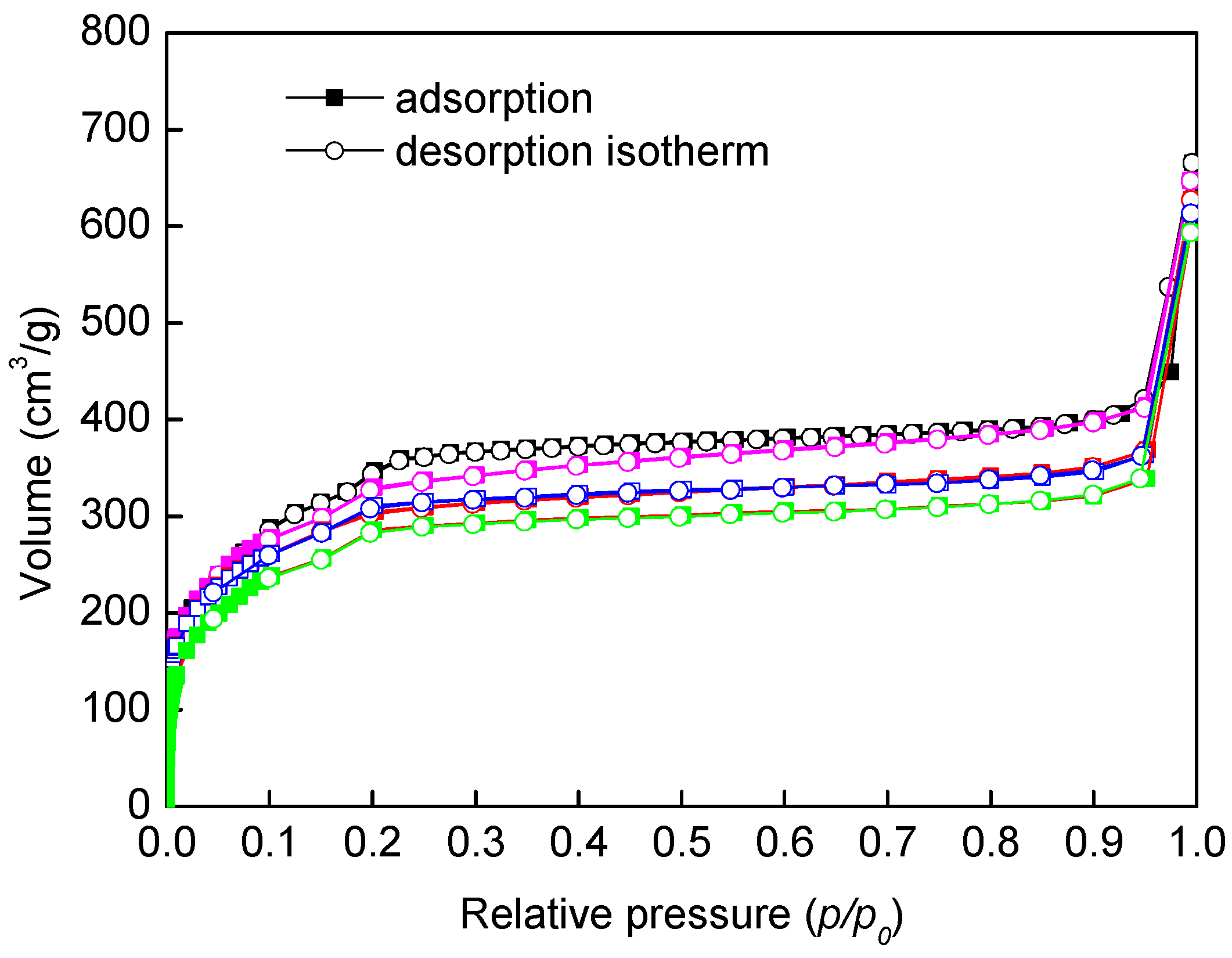

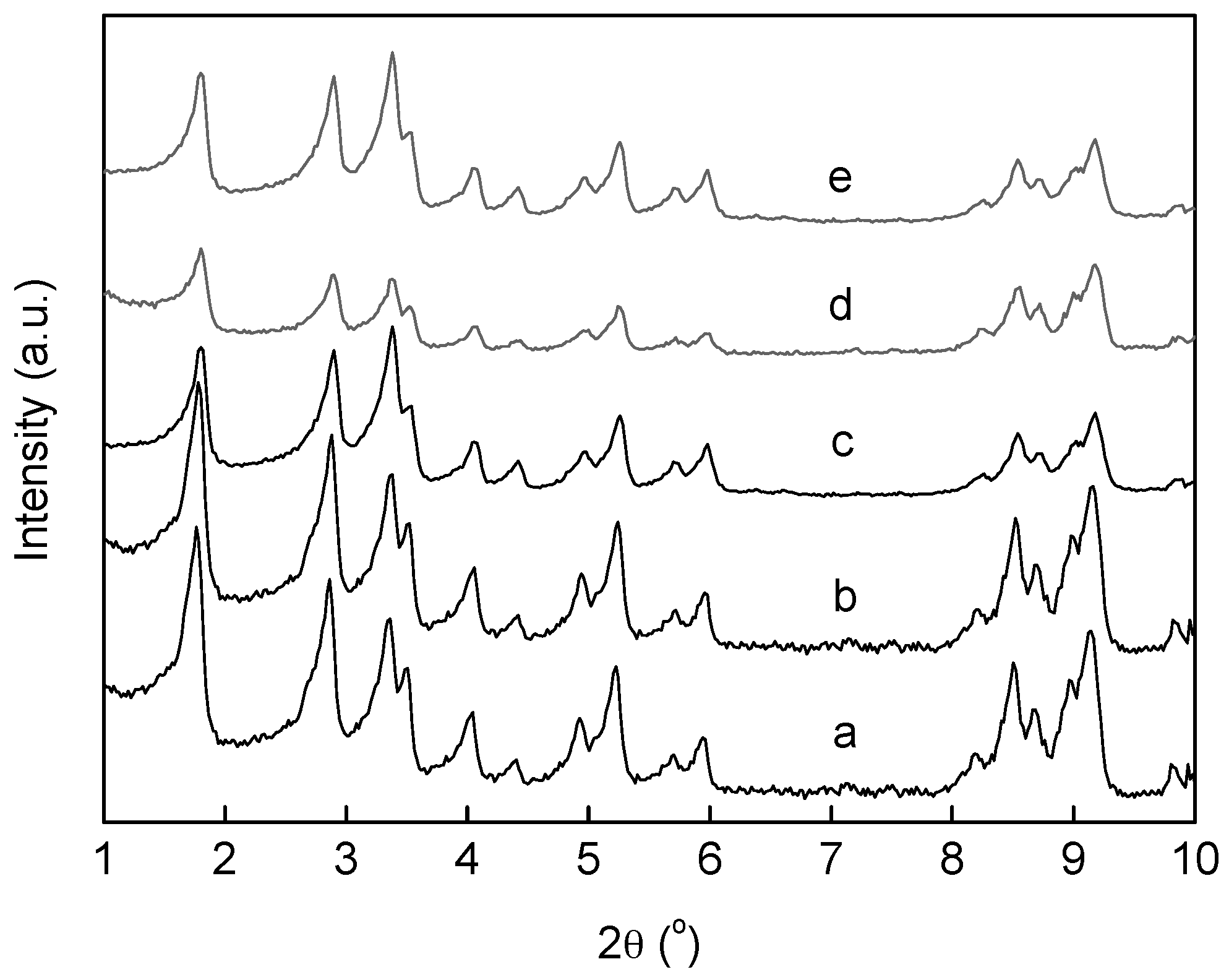

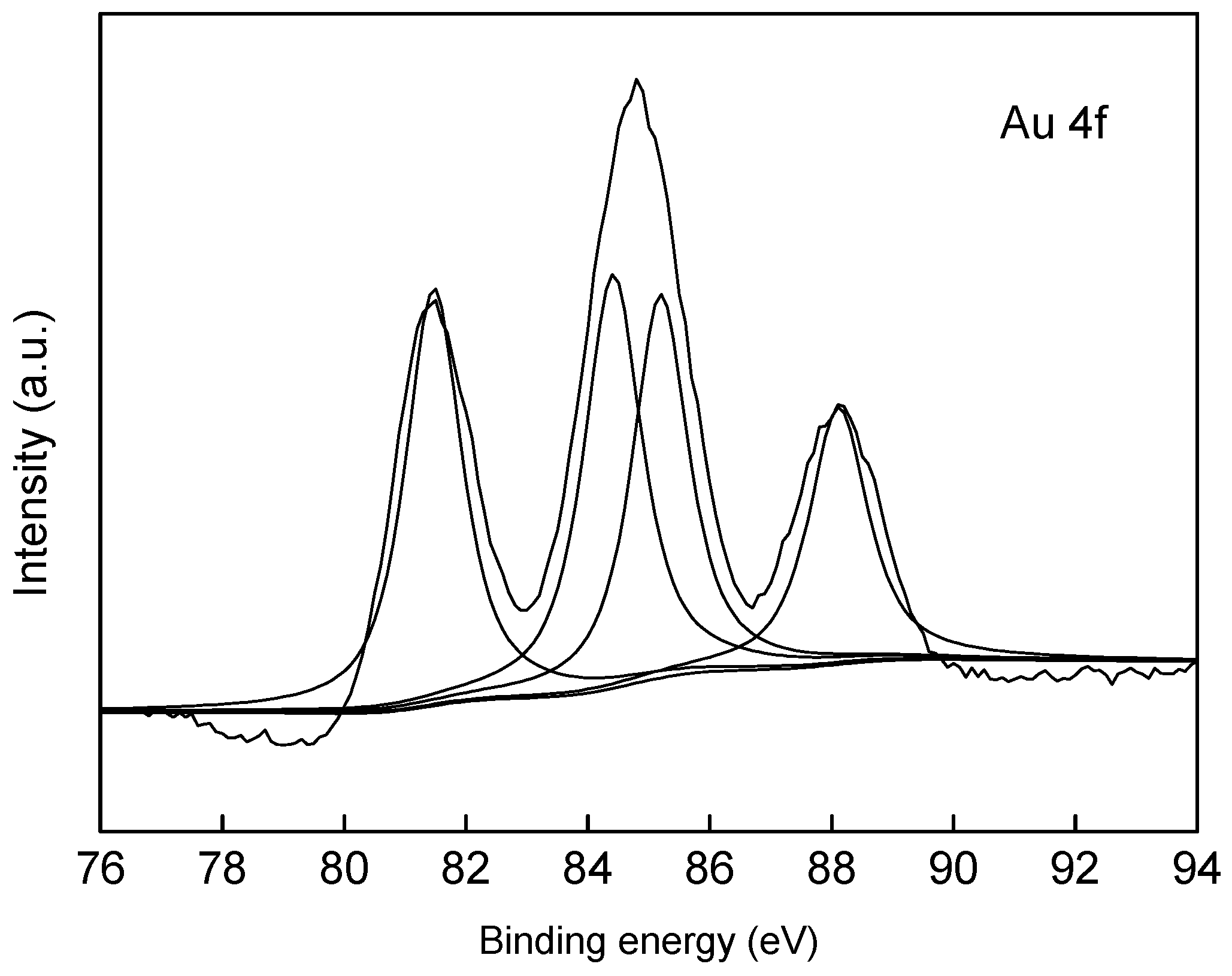

2.1. Catalyst Synthesis and Characterization

2.2. Catalytic Studies

3. Experimental Section

3.1. General Information

3.2. Catalyst Synthesis

3.2.1. Synthesis of MIL-101

3.2.2. Synthesis of EthylenediamineFunctionalized MIL-101

3.2.3. Synthesis of SalicylaldehydeFunctionalized MIL-101

3.2.4. Synthesis of Au@MIL-101-ED-SA

3.2.5. Synthesis of Au@MIL-101

3.3. General Procedure for the Three-Component Coupling Reaction

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gholinejad, M.; Saadati, F.; Shaybanizadeh, S.; Pullithadathil, B. Copper nanoparticles supported on starch micro particles as a degradable heterogeneous catalyst for three-component coupling synthesis of propargylamines. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 4983–4991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopka, I.E.; Fataftah, Z.A.; Rathke, M.W. Preparation of a series of highly hindered secondary amines, including bis(triethylcarbinyl)amine. J. Org. Chem. 1980, 45, 4616–4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blay, G.; Monleón, A.; Pedro, J. Recent development in asymmetric alkynylation of imines. Curr. Org. Chem. 2009, 13, 1498–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borah, S.J.; Das, D.K. Modified montmorillonite clay stabilized silver nanoparticles: An active heterogeneous catalytic system for the synthesis of propargylamines. Catal. Lett. 2016, 146, 656–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peshkov, V.A.; Pereshivko, O.P.; Van der Eycken, E.V. A walk around the A3-coupling. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 3790–3807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Layek, K.; Chakravarti, R.; Kantam, L.M.; Maheswaran, H.; Viru, A. Green chemistry nanocrystalline magnesium oxide stabilized gold nanoparticles: An advanced nanotechnology based recyclable heterogeneous catalyst platform for the one-pot synthesis of propargylamines. Green Chem. 2011, 13, 2878–2887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.L.; Zhang, X.; Gao, J.S.; Xu, C.M. Engineering metal–organic frameworks immobilize gold catalysts for highly efficient one-pot synthesis of propargylamines. Green Chem. 2012, 14, 1710–1720. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.L.; Tai, X.S.; Zhang, N.N.; Meng, Q.G.; Xin, C.L. Supported Au/MIL-53(Al): A reusable green solid catalyst for the three-component coupling reaction of aldehyde, alkyne, and amine. Reac. Kinet. Mech. Cat. 2016, 119, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.L.; Tai, X.S.; Yu, G.L.; Guo, H.M.; Meng, Q.G. Gold and silver nanoparticles supported on metal-organic frameworks: A highly active catalyst for three-component coupling reaction. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 2016, 32, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Bagdi, A.K.; Majee, A.; Hajra, A. Nano indium oxide catalyzed efficient synthesis of propargylamines via C–H and C–Cl bond activations. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011, 52, 4437–4439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, P.; Wang, M.; Wang, L. Indium-catalyzed highly efficient three-component coupling of aldehyde, alkyne, and amine via C–H bond activation. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 4364–4367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, R.; Sharma, S.; Gaba, G. Silica nanospheres supported diazafluorene iron complex: An efficient and versatile nanocatalyst for the synthesis of propargylamines from terminal alkynes, dihalomethane and amines. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 49198–49211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periasamy, M.; Reddy, P.O.; Edukondalu, A.; Dalai, M.; Alakonda, L.M.; Udaykumar, B. Zinc salt promoted diastereoselective synthesis of chiral propargylamines using chiral piperazines and their enantioselective conversion into chiral allenes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 2014, 6067–6076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samai, S.; Nandi, G.C.; Singh, M. An efficient and facile one-pot synthesis of propargylamines by three-component coupling of aldehydes, amines, and alkynes via C–H activation catalyzed by NiCl2. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010, 51, 5555–5558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Corma, A. Supported gold(III) catalysts for highly efficient three-component coupling reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 4358–4361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Corma, A. Efficient addition of alcohols, amines and phenol to unactivated alkenes by AuIII or PdII stabilized by CuCl2. Dalton Trans. 2008, 3, 397–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; LlabresiXamena, F.X.; Corma, A. Gold(III)–metal organic framework bridges the gap between homogeneous and heterogeneous gold catalysts. J. Catal. 2009, 265, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamami, M.; Doan, H.; Cheng, C.H. A review on breathing behaviors of metal-organic-frameworks (MOFs) for gas adsorption. Materials 2014, 7, 3198–3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saedi, Z.; Safarifard, V.; Morsali, A. Dative and covalent-dative postsynthetic modification of a two-fold interpenetration pillared-layer MOF for heterogeneous catalysis: A comparison of catalytic activities and reusability. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2016, 229, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ertas, I.E.; Gulcan, M.; Bulut, A.; Yurderi, M.; Zahmakiran, M. Metal-organic framework (MIL-101) stabilized ruthenium nanoparticles: Highly efficient catalytic material in the phenol hydrogenation. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2016, 226, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutzscher, C.; Nickerl, G.; Senkovska, I.; Bon, V.; Kaskel, S. Proline functionalized UiO-67 and UiO-68 type metal-organic frameworks showing reversed diastereoselectivity in Aldol addition reactions. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 2573–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, G.; Zeng, H.C. Synthesis and functionalization of oriented metal–organic-framework nanosheets: Toward a series of 2D catalysts. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 3268–3281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.X.; Shekhah, O.; Stammer, X.; Arslan, H.K.; Liu, B.; Schüpbach, B.; Terfort, A.; Wöll, C. Deposition of metal-organic frameworks by liquid-phase epitaxy: The influence of substrate functional group density on film orientation. Materials 2012, 5, 1581–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, H.C.; Debowski, M.; Müller, P.; Paasch, S.; Senkovska, I.; Kaskel, S.; Brunner, E. Solid-state NMR spectroscopy of metal–organic framework compounds (MOFs). Materials 2012, 5, 2537–2572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.J.; Sun, F.X.; Wang, C.R.; Pan, Q.K. Stability and hydrocarbon/fluorocarbon sorption of a metal-organic framework with fluorinated channels. Materials 2016, 9, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.B.; Lu, K.D.; Liu, D.M.; Lin, W.B. Nanoscale metal–organic frameworks for the Co-delivery of cisplatin and pooled siRNAs to enhance therapeutic efficacy in drug-resistant ovarian cancer cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 5181–5184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.R.; Sculley, J.; Zhou, H.C. Metal–organic frameworks for separations. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 869–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mon, M.; Ferrando-Soria, J.; Grancha, T.; Fortea-Pérez, F.R.; Gascon, J.; Leyva-Pérez, A.; Armentano, D.; Pardo, E. Selective gold recovery and catalysis in a highly flexible methionine-decorated metal-organic framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 7864–7867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bromberg, L.; Diao, Y.; Wu, H.; Speakman, S.A.; Hatton, T.A. Chromium(III) terephthalate metal organic framework (MIL-101): HF-free synthesis, structure, polyoxometalate composites, and catalytic properties. Chem. Mater. 2012, 24, 1664–1675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.L.; Ma, Y.Y.; Zang, H.Y.; Wang, Y.H.; Li, Y.G.; Wang, E.B. A polyoxometalate-encapsulating cationic metal–organic framework as a heterogeneous catalyst for desulfurization. Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 3778–3784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Ou, S.; Wu, C.D. Porous metal–organic frameworks for heterogeneous biomimetic catalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 1199–1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakagaki, S.; Ferreira, G.K.; Ucoski, G.M.; Dias de Freitas Castro, K.A. Chemical reactions catalyzed by metalloporphyrin-based metal-organic frameworks. Molecules 2013, 18, 7279–7308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farha, O.K.; Shultz, A.M.; Sarjeant, A.A.; Nguyen, S.T.; Hupp, J.T. Active-site-accessible, porphyrinic metal-organic framework materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 5652–5655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shultz, A.M.; Farha, O.K.; Adhikari, D.; Sarjeant, A.A.; Hupp, J.T.; Nguyen, S.T. Selective surface and near-surface modification of a noncatenated, catalytically active metal-organic framework material based on Mn(salen) struts. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 3174–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burrows, A.D.; Hunter, S.O.; Mahon, M.F.; Richardson, C. A reagentless thermal post-synthetic rearrangement of an allyloxy-tagged metal-organic framework. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 990–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manna, K.; Zhang, T.; Lin, W. Postsyntheticmetalation of bipyridyl-containing metal-organic frameworks for highly efficient catalytic organic transformations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 6566–6569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clements, J.E.; Price, J.R.; Neville, S.M.; Kepert, C.J. Perturbation of spin crossover behavior by covalent post-synthetic modification of a porous metal-organic framework. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 10164–10168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelhameed, R.M.; Carlos, L.D.; Silva, A.M.S.; Rocha, J. Near-infrared emitters based on post-synthetic modified Ln(3+)-IRMOF-3. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 5019–5021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, W.; Doonan, C.J.; Yaghi, O.M. Postsynthetic modification of a metal–organic framework for stabilization of a hemiaminal and ammonia uptake. Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 6853–6855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, Y.K.; Hong, D.Y.; Chang, J.S.; Jhung, S.H.; Seo, Y.K.; Kim, J.; Vimont, A.; Daturi, M.; Serre, C.; Férey, G. Amine grafting on coordinatively unsaturated metal centers of MOFs: Consequences for catalysis and metal encapsulation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 4144–4148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.L.; Zhang, X.; Rang, S.M.; Yang, Y.; Dai, X.P.; Gao, J.S.; Xu, C.M.; He, J. Catalysis by metal–organic frameworks: Proline and gold functionalized MOFs for the aldol and three-component coupling reactions. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 13093–13107. [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee, M.; Das, S.; Yoon, M.; Choi, H.J.; Hyun, M.H.; Park, S.M.; Seo, G.; Kim, K. Postsynthetic modification switches an achiral framework to catalytically active homochiral metal-organic porous materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 7524–7525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, Y.; Zheng, N.; Qi, Y.; Tang, J.; Wang, G. Merging metal–organic framework catalysis with organocatalysis: A thiourea functionalized heterogeneous catalyst at the nanoscale. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2014, 4, 925–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Yang, D.A.; Ahn, W.S. A new heterogeneous catalyst for epoxidation of alkenesvia one-step post-functionalization of IRMOF-3 with a manganese(ii) acetylacetonate complex. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 3637–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, T.; Zhang, L.C.; Sun, M.X.; Deng, D.Y.; Su, Y.Y.; Lv, Y. Amino-functionalized metal-organic frameworks nanoplates-based energy transfer probe for highly selective fluorescence detection of free chlorine. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 3413–3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Q.L.; Li, J.; Xu, Q. Immobilizing metal nanoparticles to metal-organic frameworks with size and location control for optimizing catalytic performance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 10210–10213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vimont, A.; Leclerc, H.; Maugé, F.; Daturi, M.; Lavalley, J.C.; Surblé, S.; Serre, C.; Férey, G. Creation of controlled Brønsted acidity on a zeotypicmesoporous chromium(III) carboxylate by grafting water and alcohol molecules. J. Phys. Chem. C 2007, 111, 383–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaerts, L.; Kirschhock, C.E.A.; Maes, M.; van der Veen, M.A.; Finsy, V.; Depla, A.; Martens, J.A.; Baron, G.V.; Jacobs, P.A.; Denayer, J.F.M.; et al. Selective adsorption and separation of xylene isomers and ethylbenzene with the microporous vanadium(IV) terephthalate MIL-47. Angew. Chem. 2007, 119, 4371–4375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Férey, G.; Mellot-Draznieks, C.; Serre, C.; Millange, F.; Dutour, J.; Surblé, S.; Margiolaki, I. A chromium terephthalate–based solid with unusually large pore volumes and surface area. Science 2005, 309, 2040–2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.L.; Liu, Y.L.; Li, Y.W.; Tang, Z.Y.; Jiang, H.F. Metal-organic framework supported gold nanoparticles as a highly active heterogeneous catalyst for aerobic oxidation of alcohols. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 13362–13369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.Z.; Pan, Y.Y.; Li, Y.W.; Yin, B.L.; Jiang, H.F. A highly active heterogeneous palladium catalyst for the Suzuki–Miyaura and Ullmann coupling reactions of aryl chlorides in aqueous media. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 4054–4058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Gao, X.L.; Wang, X.J.; Wang, Q.; Ji, Z.Y.; Wang, X.Y.; Wu, T.; Gao, C.J. Highly and stably water permeable thin film nanocomposite membranes doped with MIL-101(Cr) nanoparticles for reverse osmosis application. Materials 2016, 9, 870–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromberg, L.; Hatton, T.A. Aldehyde-alcohol reactions catalyzed under mild conditions by chromium(III) terephthalate metal organic framework (MIL-101) and phosphotungstic acid composites. ACS Appl. Mater. Int. 2011, 3, 4756–4764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gascon, J.; Aktay, U.; Hernandez-Alonso, M.D.; Klink, G.P.M.; Kapteijn, F. Amino-based metal-organic frameworks as stable, highly active basic catalysts. J. Catal. 2009, 261, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.L.; Tai, X.S.; Liu, M.F.; Li, Y.F.; Feng, Y.M.; Sun, X.R. Supported Au/MOF-5: A highly active catalyst for three-component coupling reactions. CIESC J. 2015, 66, 1738–1747. [Google Scholar]

- Tabatabaeian, K.; Zanjanchi, M.A.; Mahmoodi, N.O.; Eftekhari, T. Anchorage of a ruthenium complex into modified MOF: Synergistic effects for selective oxidation of aromatic and heteroaromatic compounds. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 101013–101022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, X.B.; Yang, J.; Wang, L. Postsynthetic modification of IRMOF-3 with a copper iminopyridine complex as heterogeneous catalyst for the synthesis of 2-aminobenzothiazoles. Appl. Organometal. Chem. 2014, 28, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horcajada, P.; Serre, C.; Maurin, G.; Ramsahye, N.A.; Balas, F.; Vallet-Regí, M.; Sebban, M.; Taulelle, F.; Férey, G. Flexible porous metal-organic frameworks for a controlled drug delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 6774–6780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.J.; Song, T.Y.; Shi, J.; Ma, K.R.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, P.; Fan, Y.; Xu, J.N. Solvothermal synthesis a novel hemidirected 2-D (3,3)-net metal-organic framework [Pb(HIDC)]n based on the linkages of left- and right-hand helical chains. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2008, 11, 192–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.L.; Zhang, X.; Gao, J.S.; Xu, C.M. Preparation and characterization of metal-organic framework supported gold catalysts and their catalytic performance for three-component coupling reaction. Chin. J. Catal. 2012, 33, 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Corma, A. Effective Au(III)–CuCl2-catalyzed addition of alcohols to alkenes. Chem. Commun. 2007, 29, 3080–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Entry | Catalyst | R1 | R2R3NH | R4 | T/h | Conv./% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Au@MIL-101-ED-SA | Ph | piperidine | Ph | 0.5 | 75.0 |

| 2 | Au@MIL-101-ED-SA | 3-ClC6H4 | piperidine | Ph | 4 | 95.2 |

| 3 | Au@MIL-101-ED-SA | 4-MeC6H4 | piperidine | Ph | 4 | 23.1 |

| 4 | Au@MIL-101-ED-SA | 4-MeOC6H4 | piperidine | Ph | 4 | 79.1 |

| 5 | Au@MIL-101-ED-SA | Cyclohexyl | piperidine | Ph | 4 | 92.9 |

| 6 | Au@MIL-101-ED-SA | Heptyl | piperidine | Ph | 4 | 98.8 |

| 7 | Au@MIL-101-ED-SA | Hexyl | piperidine | Ph | 4 | 97.6 |

| 8 | Au@MIL-101-ED-SA | Ph | pyrrolidine | Ph | 4 | 57.3 |

| 9 | Au@MIL-101-ED-SA | Ph | morpholine | Ph | 4 | 45.0 |

| 10 | Au@MIL-101-ED-SA | Ph | diethylamine | Ph | 4 | 8.8 |

| 11 | Au@MIL-101-ED-SA | Ph | piperidine | 4-MeC6H4 | 4 | 52.8 |

| 12 | Au@MIL-101-ED-SA | Ph | piperidine | 4-EtC6H4 | 4 | 51.3 |

| 13 | Au@MIL-101-ED-SA | Ph | piperidine | 4-ButC6H4 | 4 | 51.7 |

| 14 | Au@MIL-101-ED-SA | Ph | piperidine | Hexyl | 4 | 12.9 |

| 15 | Au@MIL-101-ED-SA | Ph | piperidine | (CH3)3Si | 4 | 90.9 |

| 16 | Au@MIL-101 | Ph | piperidine | Ph | 0.5 | 53.0 |

| 17 | Au@MIL-101 | 4-MeC6H4 | piperidine | Ph | 4 | 5.7 |

| 18 | Au@MIL-101 | 4-MeOC6H4 | piperidine | Ph | 4 | 48% |

| 19 | Au@MIL-101 | 3-ClC6H4 | piperidine | Ph | 4 | 56.0 |

| 20 | Au@MIL-101 | Cyclohexyl | piperidine | Ph | 4 | 93.1 |

| 21 | Au@MIL-101 | Heptyl | piperidine | Ph | 4 | 98.4 |

| 22 | Au@MIL-101 | Hexyl | piperidine | Ph | 4 | 98.3 |

| 23 | Au@MIL-101 | Ph | pyrrolidine | Ph | 4 | 40.4 |

| 24 | Au@MIL-101 | Ph | morpholine | Ph | 4 | 35.0 |

| 25 | Au@MIL-101 | Ph | diethylamine | Ph | 4 | 6.2 |

| 26 | Au@MIL-101 | Ph | piperidine | 4-MeC6H4 | 4 | 31.5 |

| 27 | Au@MIL-101 | Ph | piperidine | 4-EtC6H4 | 4 | 32.9 |

| 28 | Au@MIL-101 | Ph | piperidine | 4-ButC6H4 | 4 | 33.9 |

| 29 | Au@MIL-101 | Ph | piperidine | Hexyl | 4 | 7.3 |

| 30 | Au@MIL-101 | Ph | piperidine | (CH3)3Si | 4 | 52.6 |

, Reaction conditions: aldehyde (0.25 mmol), amine (0.30 mmol), alkyne (0.33 mmol), catalyst (0.06 g).

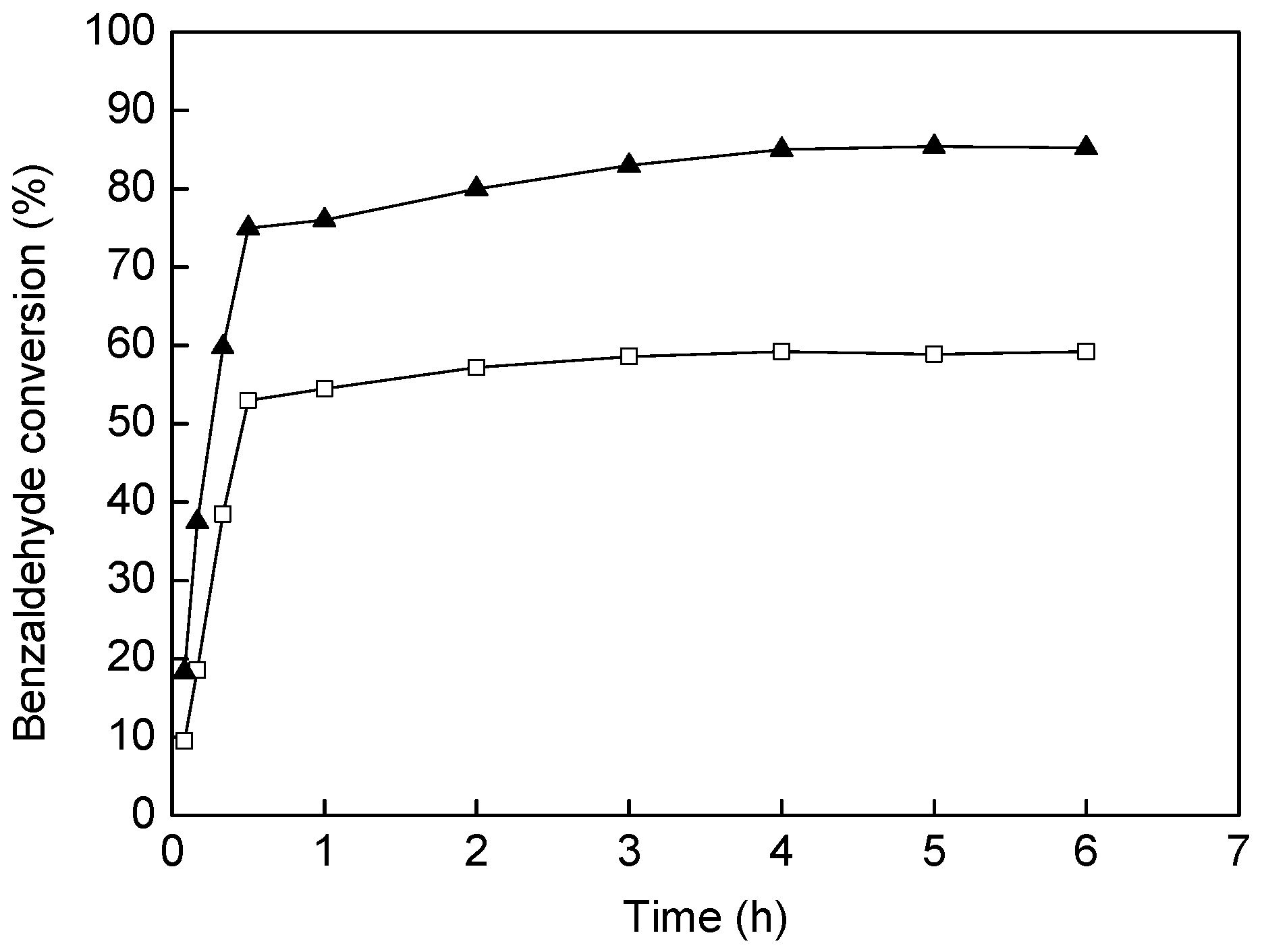

, Reaction conditions: aldehyde (0.25 mmol), amine (0.30 mmol), alkyne (0.33 mmol), catalyst (0.06 g).| Run | Catalyst | Time/h | Yield/% | Catalyst | Time/h | Yield/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Au@MIL-101-ED-SA | 0.5 | 75 | Au@MIL-101 | 0.5 | 53.0 |

| 2 | Au@MIL-101-ED-SA | 4 | 50.0 | Au@MIL-101 | 4 | 52.3 |

| 3 | Au@MIL-101-ED-SA | 4 | 45.5 | Au@MIL-101 | 4 | 48.6 |

| 4 | Au@MIL-101-ED-SA | 4 | 43.8 | Au@MIL-101 | 4 | 47.8 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, L.; Tai, X.; Zhou, X. Au3+/Au0 Supported on Chromium(III) Terephthalate Metal Organic Framework (MIL-101) as an Efficient Heterogeneous Catalystfor Three-Component Coupling Synthesis of Propargylamines. Materials 2017, 10, 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10020099

Liu L, Tai X, Zhou X. Au3+/Au0 Supported on Chromium(III) Terephthalate Metal Organic Framework (MIL-101) as an Efficient Heterogeneous Catalystfor Three-Component Coupling Synthesis of Propargylamines. Materials. 2017; 10(2):99. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10020099

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Lili, Xishi Tai, and Xiaojing Zhou. 2017. "Au3+/Au0 Supported on Chromium(III) Terephthalate Metal Organic Framework (MIL-101) as an Efficient Heterogeneous Catalystfor Three-Component Coupling Synthesis of Propargylamines" Materials 10, no. 2: 99. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma10020099