1. Introduction

A hybrid renewable energy system (HRES) is defined as a combination of several renewable technologies which can operate as a self-sustaining power system with higher efficiency than a single renewable power generator such as solar or wind system. If the proposed HRES does not guarantee the production of energy during extended periods, energy storage requirements should be considered to bridge the lean times. Battery storage can be considered as a solution. However, the concerns with the battery storage include its cost and lifetime. Beyond battery storage, a feasible solution is adding a hydrogen-based storage system including a hydrogen producer, storage tank, and hydrogen consumer such as a fuel cell. Currently, there are several hydrogen production technologies such as water electrolysis, natural gas reforming, photochemical and thermochemical splitting of water, and also a fermentation process which can be used as the hydrogen producer in a HRES. Biomass gasification via biochemical or thermochemical conversion processes are also the most practical technologies for HRES applications. However, the main concern with the gasification process is the formation of ash and tar, which causes severe technical problems such as fouling and slagging in the gasification process.

As an alternative to the conventional gasification, the supercritical water gasification (SCWG) process uses water over 22 MPa and 374 °C (critical point) as the gasifying agent to decompose the wet biomass feedstock, allowing to achieve a much higher ratio of gasification and hydrogen generation [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. Although the high cost of the feedstock is a challenging issue in utilizing the SCWG, low-cost feedstocks like sewage sludges are widely available to be used as a heavily moisture-laden feedstock in this process [

6,

7,

8,

9]. Organic wastewater and kitchen waste are considered as possible sewage sludge which do not need any drying steps, resulting in economically beneficial characteristics in the production of hydrogen [

10]. Xu and Antal [

11] performed experiments with corn starch and sewage sludge to test the effect of temperature and composition of the feedstock on carbon gasification efficiency. Casademont et al. [

12] studied the supercritical water gasification of olive oil mill waste with moisture content up to 96% wt. in a continuous stirred-tank reactor to produce hydrogen-rich gas. Several experiments were reported using the different biomass feedstock such as swine and chicken manure [

13,

14,

15]. The thermochemical conversion process of these feedstocks generates clean products with less NOx and SOx emissions in the SCWG [

16].

The combination of SCWG of biomass with fuel cell hybrid is getting attention from many scholars, but it is still a new concept. Wan et al. [

17] studied the combination of a SCWG unit and a solid oxide fuel cell which could offer high efficiency of 78.2%. Comprehensive exergy analysis of the different types of this combination was presented by Toonssen et al. [

18]. Since the gasification reactions take place at the supercritical condition (e.g., 374 °C), a large amount of heated water is needed to be used in the SCWG reactor, which requires adding an external source of thermal energy to the system. Therefore, the utilization of the heat recovery system to recover thermal energy from the flue gas of the fuel cell unit should be considered.

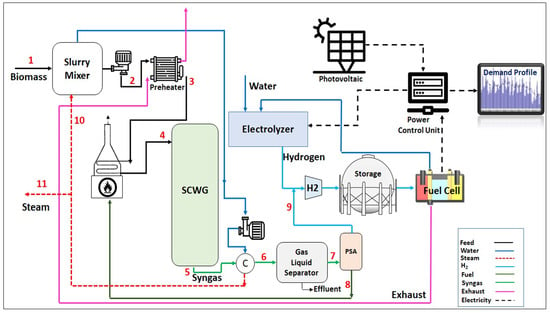

In this study, Firstly, an innovative HRES will be introduced with specific emphasis on the integration of renewable generation into the power grid. The proposed HRES is based on the combination of hydrogen generation from two sources: (1) SCWG process of the residential kitchen waste and organic wastewater and (2) solar water electrolysis process which uses the surplus electric power generated by the solar cells. The fuel cell converts hydrogen into electrical power, which can be used during the periods when the sunlight is not available. So, the proposed HRES forms a composite energy system capable of all-weather conditions. In comparison with other stand-alone power systems, the main superiorities of the proposed HRES can be addressed as follows:

The HRES itself can provide the electric power which is needed for the pre-treatment devices and auxiliary systems (i.e., pumps and mixer);

the recovered heat from the flue gas of the fuel cell can be used to preheat the feedstock;

the off-gas produced by the system can be used in a fired heater to bring the feedstock to the required reactor inlet temperature;

the surplus thermal energy from the system is available for export or other in-plant uses, such as hot utilities (hot water or steam).

Secondly, a detailed techno-economic-analysis of the proposed HRES is carried out to estimate the cost of electricity generation from the system to meet the electrical load requirements of a selected household area in a subject district around the Shinchi station which is located in Shinchi-machi in this prefecture.

2. Description of the Proposed HRES

Figure 1 shows the process flow diagram of the proposed HRES. Mixed municipal sewage sludge with a moisture content of up to 60% wt. is pumped and then preheated in a shell and tube heat exchanger which utilizes the hot flue gas from the fuel cell in its shell side. The process stream is then heated in a gas-fired trim heater to reach the gasification temperature of 650 °C before sending it to the SWC gasifier. The gasification reaction is assumed to be thermally neutral. The syngas outflow stream from the gasifier is sent to a water-cooled heat exchanger which uses cold water to lower the temperature of the syngas stream. After cooling, the gas phase of the syngas stream is separated from its liquid phase in a gas–liquid separator and depressurized to 500 psig and then enters a pressure swing adsorption (PSA) which removes its contaminants while recovering about 99.9% of the hydrogen from this stream. The off-gas outflow stream from the PSA is fed to the burners of the gas-fired trim heater. Hydrogen from the PSA unit is subsequently mixed with the hydrogen produced from the electrolyzer which can be stored in a storage tank and fed to the fuel cell. The electric power which is generated by the system can meet external loads through the electrical power output control device.

3. Simulation Model

The assumed basic reaction kinetic of glucose in a SCWG reactor is represented below [

20]:

At the supercritical condition, the lower density of water enables SCWG reactor to decompose the biomass feedstock at a faster rate than ideal gases, resulting in the production of hydrogen and methane-rich gases [

21,

22].

An optimization modeling approach based on the total Gibbs free energy minimization was developed in this paper in order to investigate the equilibrium state of the above reaction and determine the composition of the product gases, which can be explained by using the following Equation [

23]:

where:

: Mole fraction (%),

: Mole of components,

: Fugacity of components,

: Molality based activity coefficient,

: Standard molar Gibbs energy of components (KJ/mol),

: Chemical potential under standard pressure,

: Fugacity under standard pressure,

: Gasification reaction temperature (K),

: Gas constant (8.314 J K−1 mol−1),

: Components in their gaseous and aqueous phases.

Throughout this paper, the required values for

and

have been obtained from the Aspen HYSYS software. Molality-based activity coefficients for aqueous phases were given in [

24]. The fugacity coefficients were estimated by developing the Peng−Robinson Equation of state has as follows [

25]:

and

where

Z is the compressibility factor (

Z =

pv/

RT). The subscripts c and ω refer to the critical point and the acentric factor of the substance, respectively.

Tc = 373.95 C and

Pc = 220.64 bar. The maximum and minimum roots of Equation (4) refer to the gas and liquid phases of the two-phase region. The total Gibbs energy in Equation (2) should be minimized with respect to

nij (

i = 1, 2, …,

ni;

j = 1, 2, …,

nj) subject to the following constraints:

and the optimum mole numbers of the product gases at the equilibrium state can be found as

The above Equations (2)–(9) were then formulated as a constrained non-linear programming problem, and the CONOPT solver of general algebraic modeling system (GAMS) was used to find the minimum value of the total Gibbs free energy (Equation (2)) as the objective function of the system.

For a fuel cell stack with the following reactions, the output power may be calculated by using Equation (10):

where:

: Gibbs free energy of the fuel cell reaction (),

: Molecular weight of hydrogen (g/mole),

: Mass flow rate of hydrogen (g/s),

: Fuel cell electric power (W),

: Maximum efficiently of hydrogen conversion (40–60%).

In a hydrogen-fed fuel cell, water is produced at the rate of one mole for every two electrons. So, the following Equation is adapted to calculate the amount of produced water,

(g/s), from the Fuel cell:

F refers to the Faraday constant, which is about 96,485 (C/mole) (C: Coulomb is the equivalent of one ampere-second)

is the Fuel cell average voltage (V).

is the molecular weight of water (g/mole). To calculate the amount of heat produced by the fuel cell the following Equation may be used:

where,

1.25 V, is the actual voltage of the fuel cell stack. Further details on fuel cell modeling are given in [

26,

27].

The amount of hydrogen generated from the electrolyzer can be calculated as follows:

where:

: Amount of hydrogen generated from the electrolyzer (kg),

: Amount of electricity used in the electrolyzer (kWh),

: Hydrogen production efficiency 65% to 85% [

28], and

: Calorific value of hydrogen (39.4 kWh/kg)

The electrical output power from the solar panels can be estimated by using the below formula [

29,

30]:

where:

: Output power from the solar panel per panel area (W/m2),

: Temperature coefficient of the panel (1/°C),

: Rated power under the reference conditions (W/m2),

: 1000 (W/m2),

: Reference temperature (25 °C),

: Solar cell temperature, and

: Incident solar radiation on the titled surface (W/m2).

The level of hydrogen in the storage tank at time step (t) is estimated based on the amount of hydrogen inflow from the electrolyzer and SCWG at time step (t), and amount of hydrogen outflow to the fuel cell at the time (t):

is the storage efficiency which is assumed to be about 90%. Furthermore, there is upper () and lower limit () for hydrogen level. The upper limit is about 80% of the nominal capacity of tank and lower limit is considered 5% of the rated capacity.

Figure 2 shows the management strategy, which is used to control the amount of power and hydrogen generated by the different components in the proposed HRES.

In this approach, the renewable energy sources (biomass and solar) plus the energy stored in the hydrogen storage are used to cover the demand. The fuel cell is switched on as a backup source when solar energy is not sufficient to supply the load. For each hour step, the simulation program compares the required energy demand and the supplied energy, and according to the difference, a decision to operate the water electrolyzer and SCWG or to charge the hydrogen or discharge it will be taken. The following cases will be considered with the illustrated priority while developing the simulation model:

Case I: The solar PV supplies sufficient generated energy. The use of this energy to supply the load has preference over using the Fuel Cell. The extra energy generated by the solar PV is used in the water electrolyzer to generate hydrogen which will be stored in the hydrogen storage.

Case II: The generated energy by solar PV is not sufficient to supply the load (e.g., during night time). The priority here is to use the Fuel cell. If the hydrogen level is lower than the upper limit () in the storage tank, then the decision to operate SCWG to generate additional hydrogen will be taken by the simulation model.

4. Study Area

The developed modeling approach was used to estimate the amount of electrical power which can be generated by the proposed HRES and will be needed to satisfy the electrical load requirements in the selected residential area in a subject district around Shinchi station in Fukushima prefecture. This district belongs to the Tohoku region, which the Great East Japan Earthquake occurred there (See

Figure 3). The selected area includes 10 detached standard Japanese houses with a daily peak electric power load about 14 kW and total annual electricity consumption of 43,700 kWh.

The details of hourly electricity consumption and solar irradiation in the selected residential area are shown in

Figure 4. The solar radiation data was collected from the weather station ID: 47595 in Fukushima prefecture [

31].

Figure 5 shows the hourly load profile of the typical household in the selected area [

32].

5. Results and Discussions

5.1. Heat and Mass Balances

Table 1 shows the assumed chemical composition for the typical kitchen waste as the primary source of wet biomass feed used in the SCWG process.

The influence of reaction temperature and biomass feedstock moisture content on SCWG product gas are depicted in

Figure 6. It can be observed from this figure that, by increasing the reaction temperature, the concentration of hydrogen and carbon monoxide in the product gas increases. The results also revealed that as the feedstock moisture content increases from about 40 wt.% up to 70 wt.%, carbon dioxide and hydrogen yields increase remarkably.

Comparison between the SCWG model developed here with experimental data is validated in

Table 2, in terms of hydrogen yields. The biomass feedstock is glucose for all cases. Different operating temperature and pressure are reported in the experiments. As can be seen the model captures the experimental data well at the operating temperature of 650 °C.

The result of heat and mass balances based on using 1 kg/h of biomass feedstock is presented in

Table 3. The amount of required thermal energy for increasing the slurry feed temperature to 650 °C is H

4 − H

3 = 1104.6 KJ/h which can be provided from burning the off-gas (H

8 = 1268.15 kJ/h) in the gas-fired trim heater. The result also indicates that the amount of process steam produced from the cooler (H

10 = 725.5 kJ/h) is sufficient to heat the slurry feed (H

2 = 517.1 kJ/kg).

5.2. Electricity Generation

Figure 7 represents the supply-demand balance of electricity in 2018. The annual demand of electricity in the selected residential area is about 43,700 kWh which about 12,279 kWh of this amount can be provided by the solar panel which is less than 40% of the total electricity demand in this area. The input technical data of the solar panel used in the simulation model are listed in

Table 4.

5.3. Hydrogen Production and Biomass Consumption

The total annual hydrogen production is estimated at 2850 kg, using the annual wet biomass consumption of 98 tons of possible materials include kitchen waste and organic waste. The total hydrogen generated by the electrolyzer and SCWG was estimated at about 74 kg and 2776 kg by the model, respectively. According to the Ministry of the Environment, Japan, a standard Japanese household generates about 3.2 kg of garbage per day and about 33% of this amount includes wet kitchen waste [

38]. Therefore, using additional sources of wet biomass such as sewage sludge from the nearby commercial buildings needs to be considered in this area.

5.4. Cost Analysis

Various scholars have reported cost estimates for the SCWG, which varies in a broad range (see

Table 5).

The total capital cost of the proposed HRES was estimated at around USD 311,000 based on the detailed estimation of the size and capacity of each component is reported in

Table 6.

The economic analysis of the proposed HRES was based on calculating the levelized cost of electricity (LCOE) of the proposed system, using the following formula [

42]:

: Electricity generation in year t,

: Discount rate (%). It is assumed to be 0.3% in Japan,

: Lifetime of the system,

: Opex in year t,

: Capex in year t.

Based on the data reported in

Table 4, the levelized cost of energy (LCOE) of the system, including electricity, was estimated at 0.9

$/kWh which is much higher than the average electricity tariff in Japan (0.25

$/kWh). The model was employed to perform sensitivity analyses of the LCOE with respect to the size of solar-powered hydrogen generation system (Solar PV + electrolyzer). The result of the sensitivity analysis shows that the substitution of biomass hydrogen with solar hydrogen can significantly influence the LCOE of the system. As can be seen in

Figure 8, by increasing the amount of hydrogen produced by the electrolyzer, the total cost of the system increases. Therefore, the reduction of the cost of the solar hydrogen system turns out to be by far the most important cost driver.

However, If the use of excess thermal energy for in-plant purposes is included, the LCOE of the HRES will be about 0.38

$/kWh. The amounts of extra thermal energy available from the HRES are given in

Table 7.

5.5. Water Supply

Consider a cell voltage of 0.7 V which corresponds to an efficiency of 45%, the total amount of produced water from the fuel cell in the proposed HRES is about 15.1 ton per year which more than the amount of water requirement in the electrolyzer. The extra produced water can be used as the makeup water in the sludge mixer.

5.6. CO2 Emission Reduction

The following formula was used to estimate the reduction in CO

2 emission from using the proposed HRES in the selected residential area:

where,

is the annual CO

2 emission reduction by using the proposed HRES (t);

is the annual surplus heat quantity (MJ);

is the annual electricity generation from the system (kWh).

is the CO

2 emission factor of liquefied natural gas (LNG) which is supplied from the Soma LNG terminal via Soma-Iwanuma Gas Pipeline to the Shinchi-machi region (kg

CO2e/Kg

LNG).

is the CO

2 emission factor of the grid electricity generated by proposed HRES in Shinchi-machi (kg

CO2e/KWh) and

is the calorific heat of LNG (MJ/kg).

Given the standard values for for

and

, the expected CO

2 emission reduction from using the proposed HRES to provide electricity for 10 detached houses in the selected residential area is estimated at about 21 tons per year (see

Table 8).

6. Conclusions

The hybridization of various renewable energy sources can allow for smooth, stable, and reliable output to power grids to improve the safety, reliability, and stability of dispatched power, which is more efficient and cheaper than investing in dedicated energy storage options. The most important advantage of the proposed HRES is to make the optimum use of power technologies to tackle limitations on fuel availability, emissions, and economics.

In this study, to promote the application of the HRES, a novel system based on the integration of solar water electrolysis and supercritical water gasification of wet biomass feedstock was proposed. The detailed techno-economic analysis of the proposed HRES was carried in order to provide electricity, heat, hydrogen, and water from aqueous sludge, including kitchen waste and organic waste in a selected residential area in Shinchi-machi, Fukushima prefecture, Japan. The result of the cost analysis of the specific case which was addressed in this paper showed that although the capital requirement of the system is much higher than a single renewable technology, when the excess heat revenue of the HRES is taking into account, the LCOE decreases to the level near to average electricity tariff in Japan.