Strontium Peroxide-Loaded Composite Scaffolds Capable of Generating Oxygen and Modulating Behaviors of Osteoblasts and Osteoclasts

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of SrO2 + MnO2@PLGA/Gelatin Scaffolds

2.3. Oxygen and Sr2+ Release Profile of SrO2 + MnO2@PLGA/Gelatin Scaffolds

2.4. Cell Culture

2.5. Biocompatibility of SrO2 + MnO2@PLGA/Gelatin Scaffolds

2.6. Osteoclast Differentiation

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. SrO2 + MnO2@PLGA/Gelatin Scaffolds Releases Oxygen and Strontium Ion

3.2. SrO2 + MnO2@PLGA/Gelatin Scaffolds Promote Proliferation of Preosteoblasts

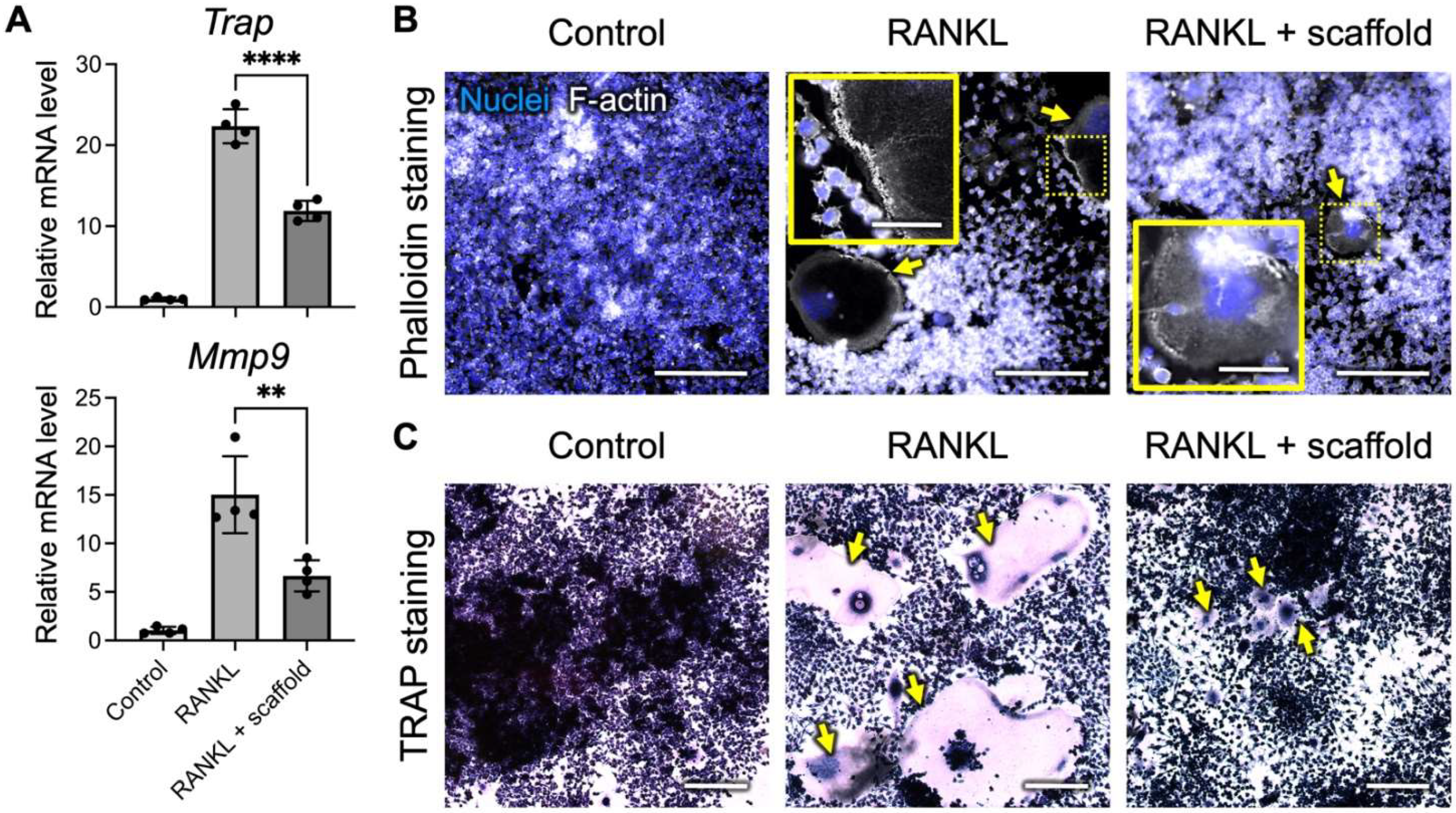

3.3. SrO2 + MnO2@PLGA/Gelatin Scaffolds Inhibit Osteoclast Differentiation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yaszemski, M.J.; Payne, R.G.; Hayes, W.C.; Langer, R.; Mikos, A.G. Evolution of bone transplantation: Molecular, cellular and tissue strategies to engineer human bone. Biomaterials 1996, 17, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhumiratana, S.; Bernhard, J.C.; Alfi, D.M.; Yeager, K.; Eton, R.E.; Bova, J.; Shah, F.; Gimble, J.M.; Lopez, M.J.; Eisig, S.B.; et al. Tissue-engineered autologous grafts for facial bone reconstruction. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 343ra83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Balogh, Z.J.; Reumann, M.K.; Gruen, R.L.; Mayer-Kuckuk, P.; Schuetz, M.A.; Harris, I.A.; Gabbe, B.J.; Bhandari, M. Advances and future directions for management of trauma patients with musculoskeletal injuries. Lancet 2012, 380, 1109–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Merchan, E.C. Bone healing materials in the treatment of recalcitrant nonunions and bone defects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bez, M.; Sheyn, D.; Tawackoli, W.; Avalos, P.; Shapiro, G.; Giaconi, J.C.; Da, X.Y.; Ben David, S.; Gavrity, J.; Awad, H.A.; et al. In situ bone tissue engineering via ultrasound-mediated gene delivery to endogenous progenitor cells in mini-pigs. Sci. Transl. Med. 2017, 9, eaal3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, Y.H.; Zheng, Z.W.; Zhou, R.P.; Zhang, H.Z.; Chen, C.S.; Xiong, Z.Z.; Liu, K.; Wang, X.S. Developing a strontium-releasing graphene oxide-/collagen-based organic inorganic nanobiocomposite for large bone defect regeneration via mapk signaling pathway. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 15986–15997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, Z.-K.; Lai, P.-L.; Toh, E.K.-W.; Weng, C.-H.; Tseng, H.-W.; Chang, P.-Z.; Chen, C.-C.; Cheng, C.-M. Osteogenic differentiation of preosteoblasts on a hemostatic gelatin sponge. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 32884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Tian, X.Z.; Cui, G.; Zhao, Y.M.; Yang, Q.; Yu, S.L.; Xing, G.S.; Zhang, B.X. Segmental bone regeneration using an rhbmp-2-loaded gelatin/nanohydroxyapatite/fibrin scaffold in a rabbit model. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 6276–6285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Z.Y.; Fang, Z.W.; Yang, Y.Q.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.G.; Kang, J.; Qu, X.H.; Yuan, W.E.; Dai, K.R. Strontium ranelate-loaded PLGA porous microspheres enhancing the osteogenesis of mc3t3-e1 cells. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 24607–24615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mao, Z.Y.; Li, Y.; Yang, Y.Q.; Fang, Z.W.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.G.; Kang, J.; Qu, X.H.; Yuan, W.E.; Dai, K.R.; et al. Osteoinductivity and antibacterial properties of strontium ranelate-loaded poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) microspheres with assembled silver and hydroxyapatite nanoparticles. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazimierczak, P.; Przekora, A. Bioengineered living bone grafts-a concise review on bioreactors and production techniques in vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, J.Q.; Yu, T.Q.; Hu, B.Y.; Wu, H.W.; Ouyang, H.W. Current biomaterial-based bone tissue engineering and translational medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sbricoli, L.; Guazzo, R.; Annunziata, M.; Gobbato, L.; Bressan, E.; Nastri, L. Selection of collagen membranes for bone regeneration: A literature review. Materials 2020, 13, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kane, R.J.; Roeder, R.K. Effects of hydroxyapatite reinforcement on the architecture and mechanical properties of freeze-dried collagen scaffolds. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2012, 7, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kane, R.J.; Weiss-Bilka, H.E.; Meagher, M.J.; Liu, Y.X.; Gargac, J.A.; Niebur, G.L.; Wagner, D.R.; Roeder, R.K. Hydroxyapatite reinforced collagen scaffolds with improved architecture and mechanical properties. Acta Biomater. 2015, 17, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, R.; Chen, S.Y.; Zhao, W.L.; Yang, L.; Yuan, B.; Voicu, S.I.; Antoniac, I.V.; Yang, X.; Zhu, X.D.; Zhang, X.D. A bioceramic scaffold composed of strontium-doped three-dimensional hydroxyapatite whiskers for enhanced bone regeneration in osteoporotic defects. Theranostics 2020, 10, 1572–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prabha, R.D.; Nair, B.P.; Ditzel, N.; Kjems, J.; Nair, P.D.; Kassem, M. Strontium functionalized scaffold for bone tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 94, 509–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, K.L.; Xia, L.G.; Li, H.Y.; Jiang, X.Q.; Pan, H.B.; Xu, Y.J.; Lu, W.W.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Chang, J. Enhanced osteoporotic bone regeneration by strontium-substituted calcium silicate bioactive ceramics. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 10028–10042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.G.; Zhou, X.J.; Qiu, K.X.; Feng, W.; Mo, H.M.; Wang, M.Q.; Wang, J.W.; He, C.L. Strontium-incorporated mineralized plla nanofibrous membranes for promoting bone defect repair. Colloids Surf. B-Biointerfaces 2019, 179, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.D.; Zandieh-Doulabi, B.; Klein-Nulend, J. Strontium ranelate affects signaling from mechanically-stimulated osteocytes towards osteoclasts and osteoblasts. Bone 2013, 53, 112–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodziejska, B.; Stepien, N.; Kolmas, J. The influence of strontium on bone tissue metabolism and its application in osteoporosis treatment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 6564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burlet, N.; Reginster, J.Y. Strontium ranelate—The first dual acting treatment for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2006, 443, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.J.; Lei, B.; Li, X.; Mo, Y.F.; Wang, R.X.; Chen, D.F.; Chen, X.F. Promoting in vivo early angiogenesis with sub-micrometer strontium-contained bioactive microspheres through modulating macrophage phenotypes. Biomaterials 2018, 178, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, P.F.; Jing, W.; Yuan, Z.Y.; Huang, Y.Q.; Guan, B.B.; Zhang, W.X.; Zhang, X.; Mao, J.P.; Cai, Q.; Chen, D.F.; et al. Vancomycin- and strontium-loaded microspheres with multifunctional activities against bacteria, in angiogenesis, and in osteogenesis for enhancing infected bone regeneration. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 30596–30609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Saless, N.; Wang, X.; Sinha, A.; Decker, S.; Kazakia, G.; Hou, H.; Williams, B.; Swartz, H.M.; Hunt, T.K.; et al. The role of oxygen during fracture healing. Bone 2013, 52, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gómez-Barrena, E.; Rosset, P.; Lozano, D.; Stanovici, J.; Ermthaller, C.; Gerbhard, F. Bone fracture healing: Cell therapy in delayed unions and nonunions. Bone 2015, 70, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Park, S.; Park, K.M. Hyperbaric oxygen-generating hydrogels. Biomaterials 2018, 182, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farris, A.L.; Rindone, A.N.; Grayson, W.L. Oxygen delivering biomaterials for tissue engineering. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 3422–3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Bawa, H.K.; Ng, G.; Wu, Y.; Libera, M.; van der Mei, H.C.; Busscher, H.J.; Yu, X. Oxygen-generating nanofiber cell scaffolds with antimicrobial properties. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2011, 3, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, C.C.; Chia, W.T.; Chung, M.F.; Lin, K.J.; Hsiao, C.W.; Jin, C.; Lim, W.H.; Chen, C.C.; Sung, H.W. An implantable depot that can generate oxygen in situ for overcoming hypoxia-induced resistance to anticancer drugs in chemotherapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 5222–5225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, H.; Buizer, A.T.; Woudstra, W.; Veldhuizen, A.G.; Bulstra, S.K.; Grijpma, D.W.; Kuijer, R. Control of oxygen release from peroxides using polymers. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2015, 26, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsieh, T.E.; Lin, S.J.; Chen, L.C.; Chen, C.C.; Lai, P.L.; Huang, C.C. Optimizing an injectable composite oxygen-generating system for relieving tissue hypoxia. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholipourmalekabadi, M.; Zhao, S.; Harrison, B.S.; Mozafari, M.; Seifalian, A.M. Oxygen-generating biomaterials: A new, viable paradigm for tissue engineering? Trends Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 1010–1021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pedraza, E.; Coronel, M.M.; Fraker, C.A.; Ricordi, C.; Stabler, C.L. Preventing hypoxia-induced cell death in beta cells and islets via hydrolytically activated, oxygen-generating biomaterials. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 4245–4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, C.Y.; Hsu, Y.H.; Chen, Y.; Yang, L.C.; Tseng, S.C.; Chen, W.R.; Huang, C.C.; Wan, D. Robust o2 supplementation from a trimetallic nanozyme-based self-sufficient complementary system synergistically enhances the starvation/photothermal therapy against hypoxic tumors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 38090–38104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, P.C.; Chen, S.C.; Hsueh, Y.J.; Shen, Y.C.; Tsai, M.Y.; Hsu, L.W.; Yeh, C.K.; Chen, H.C.; Huang, C.C. Gelatin scaffold with multifunctional curcumin-loaded lipid-PLGA hybrid microparticles for regenerating corneal endothelium. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2021, 120, 111753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.C.; Chen, Y.H.; Chiu, H.; Ko, Y.H.; Wang, R.T.; Wang, W.P.; Chuang, Y.J.; Huang, C.C.; Lu, T.T. Cell-penetrating delivery of nitric oxide by biocompatible dinitrosyl iron complex and its dermato-physiological implications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, C.E.; Fang, Y.Q.; Ho, C.T.; Assunção, M.; Lin, S.J.; Wang, Y.C.; Blocki, A.; Huang, C.C. Bioactive decellularized extracellular matrix derived from 3d stem cell spheroids under macromolecular crowding serves as a scaffold for tissue engineering. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2021, 10, 2100024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.C.; Yang, X.B.; Lei, Y.S.; Zhang, Z.; Smith, W.L.; Yan, J.L.; Kong, L.B. Evaluation of efficacy on rankl induced osteoclast from raw264.7 cells. J. Cell Physiol. 2019, 234, 11969–11975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustin, S.A.; Benes, V.; Garson, J.A.; Hellemans, J.; Huggett, J.; Kubista, M.; Mueller, R.; Nolan, T.; Pfaffl, M.W.; Shipley, G.L.; et al. The miqe guidelines: Minimum information for publication of quantitative real-time pcr experiments. Clin. Chem. 2009, 55, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lin, Y.J.; Lee, Y.W.; Chang, C.W.; Huang, C.C. 3d spheroids of umbilical cord blood msc-derived schwann cells promote peripheral nerve regeneration. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 604946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.Y.; Chen, L.C.; Jhuang, Y.T.; Lin, Y.J.; Hung, P.Y.; Ko, Y.C.; Tsai, M.Y.; Lee, Y.W.; Hsu, L.W.; Yeh, C.K.; et al. Injection of hybrid 3d spheroids composed of podocytes, mesenchymal stem cells, and vascular endothelial cells into the renal cortex improves kidney function and replenishes glomerular podocytes. Bioeng. Transl. Med. 2021, 6, e10212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, A.; Guha, P.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Bandyopadhyay, S.K. Biphasic activity of resveratrol on indomethacin-induced gastric ulcers. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 381, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedermair, T.; Schirner, S.; Seebroker, R.; Straub, R.H.; Grassel, S. Substance p modulates bone remodeling properties of murine osteoblasts and osteoclasts. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 9199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamajima, K.; Hamamura, K.; Chen, A.; Yokota, H.; Mori, H.; Yo, S.; Kondo, H.; Tanaka, K.; Ishizuka, K.; Kodama, D.; et al. Suppression of osteoclastogenesis via α2-adrenergic receptors. Biomed. Rep. 2018, 8, 407–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alshammari, H.; Neilands, J.; Svensater, G.; Stavropoulos, A. Antimicrobial potential of strontium hydroxide on bacteria associated with peri-implantitis. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.; Kwon, J.; Khang, G.; Lee, D. Reduction of inflammatory responses and enhancement of extracellular matrix formation by vanillin-incorporated poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) scaffolds. Tissue Eng. Part A 2012, 18, 1967–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Oh, S.H.; Ward, C.L.; Atala, A.; Yoo, J.J.; Harrison, B.S. Oxygen generating scaffolds for enhancing engineered tissue survival. Biomaterials 2009, 30, 757–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.; Wang, D.H.; Cao, H.L.; Qiao, Y.Q.; Zhu, H.Q.; Liu, X.Y. Effect of local alkaline microenvironment on the behaviors of bacteria and osteogenic cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 42018–42029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmagnola, I.; Chiono, V.; Ruocco, G.; Scalzone, A.; Gentile, P.; Taddei, P.; Ciardelli, G. PLGA membranes functionalized with gelatin through biomimetic mussel-inspired strategy. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.S.; Kim, T.G.; Park, T.G. Surface-functionalized electrospun nanofibers for tissue engineering and drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2009, 61, 1033–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohanizadeh, R.; Swain, M.V.; Mason, R.S. Gelatin sponges (gelfoam) as a scaffold for osteoblasts. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2008, 19, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristallini, C.; Cibrario Rocchietti, E.; Gagliardi, M.; Mortati, L.; Saviozzi, S.; Bellotti, E.; Turinetto, V.; Sassi, M.P.; Barbani, N.; Giachino, C. Micro- and macrostructured PLGA/gelatin scaffolds promote early cardiogenic commitment of human mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. Stem Cells Int. 2016, 2016, 7176154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Norouzi, M.; Shabani, I.; Ahvaz, H.H.; Soleimani, M. PLGA/gelatin hybrid nanofibrous scaffolds encapsulating egf for skin regeneration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2015, 103, 2225–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, Z.X.; Wang, Y.S.; Ma, C.; Zheng, W.; Li, L.; Zheng, Y.F. Electrospinning of PLGA/gelatin randomly-oriented and aligned nanofibers as potential scaffold in tissue engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2010, 30, 1204–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhao, F.J.; Huang, D.Q.; Fu, X.L.; Li, X.; Chen, X.F. Strontium-substituted submicrometer bioactive glasses modulate macrophage responses for improved bone regeneration. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 30747–30758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, B.G.; Xiong, W.; Xu, N.; Guan, H.F.; Fang, Z.; Liao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, B.; Xiao, X.; Fu, J.J.; et al. Strontium-loaded titania nanotube arrays repress osteoclast differentiation through multiple signalling pathways: In vitro and in vivo studies. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.J.; Hu, X.Y.; Tao, Y.X.; Ping, Z.C.; Wang, L.L.; Shi, J.W.; Wu, X.X.; Zhang, W.; Yang, H.L.; Nie, Z.K.; et al. Strontium inhibits titanium particle-induced osteoclast activation and chronic inflammation via suppression of nf-kappa b pathway. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnelye, E.; Chabadel, A.; Saltel, F.; Jurdic, P. Dual effect of strontium ranelate: Stimulation of osteoblast differentiation and inhibition of osteoclast formation and resorption in vitro. Bone 2008, 42, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangashetti, L.S.; Khapli, S.M.; Wani, M.R. Il-4 inhibits bone-resorbing activity of mature osteoclasts by affecting nf-kappa b and ca2+ signaling. J. Immunol. 2005, 175, 917–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, L.; Wu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, Z. Hypoxia promotes the proliferation of mc3t3-e1 cells via the hypoxia-inducible factor-1α signaling pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 5267–5273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Utting, J.C.; Robins, S.P.; Brandao-Burch, A.; Orriss, I.R.; Behar, J.; Arnett, T.R. Hypoxia inhibits the growth, differentiation and bone-forming capacity of rat osteoblasts. Exp. Cell Res. 2006, 312, 1693–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, T.R.; Gibbons, D.C.; Utting, J.C.; Orriss, I.R.; Hoebertz, A.; Rosendaal, M.; Meghji, S. Hypoxia is a major stimulator of osteoclast formation and bone resorption. J. Cell Physiol. 2003, 196, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.K.; Mohamad Hazir, N.S.; Alias, E. Impacts of hypoxia on osteoclast formation and activity: Systematic review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lin, S.-J.; Huang, C.-C. Strontium Peroxide-Loaded Composite Scaffolds Capable of Generating Oxygen and Modulating Behaviors of Osteoblasts and Osteoclasts. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 6322. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23116322

Lin S-J, Huang C-C. Strontium Peroxide-Loaded Composite Scaffolds Capable of Generating Oxygen and Modulating Behaviors of Osteoblasts and Osteoclasts. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2022; 23(11):6322. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23116322

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Sheng-Ju, and Chieh-Cheng Huang. 2022. "Strontium Peroxide-Loaded Composite Scaffolds Capable of Generating Oxygen and Modulating Behaviors of Osteoblasts and Osteoclasts" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23, no. 11: 6322. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23116322