Mitochondria in Neuroprotection by Phytochemicals: Bioactive Polyphenols Modulate Mitochondrial Apoptosis System, Function and Structure

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction are the Major Pathogenic Factors in Neurodegeneration

2.1. Production of Reactive Oxidative Species and Mitochondrial Dysfunction

2.2. Structure and Regulation of Mitochondrial Apoptosis System

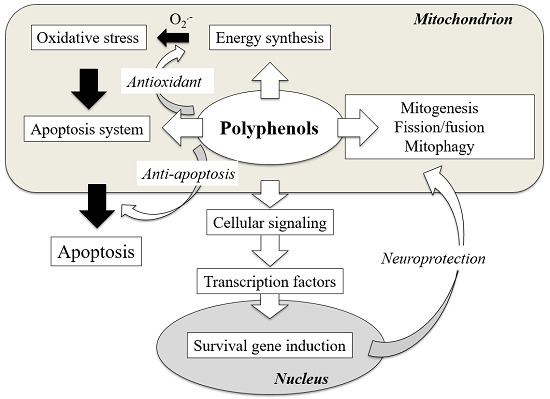

3. Polyphenols Modulate Mitochondrial Function and Exhibit Neuroprotection

3.1. Structure and Anti-Oxidant Function of Polyphenols

3.2. Polyphenols Prevent Apoptosis by Direct Regulation of Apoptosis System in Mitochondria

3.3. Polyphenols Enhance Mitochondrial Biogenesis

3.4. Polyphenols Influence Mitochondrial Fission and Fusion

3.5. Polyphenols Affect Mitophagy and Control Mitochondrial Quality

4. Polyphenols Induce Cell Death in Cancer by Activation of Mitochondrial Apoptosis System

5. Synthesis of Mitochondria-Targeting Polyphenols

6. Discussion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMPK | AMP-activated protein kinase |

| ANT | adenine nucleotide translocator |

| ARE | antioxidant responsive element |

| Atg | autophagy-related gene |

| CK | creatine kinase |

| CREB | cAMP response element-binding protein |

| CysA | cyclosporine A |

| CypD | cyclophilin D |

| Cytc | cytochrome c |

| ∆Ψm | mitochondrial membrane potential |

| Drp1 | dynamin related protein 1 |

| F-ATPase | F1-F0 ATP synthase |

| GABARAP | GABA receptor-associated protein |

| GSK-3 | β glycogen synthase kinase-3β |

| HO-1 | heme oxygenase-1 |

| HK | hexokinase |

| IMM | Inner mitochondrial membrane |

| LC3 | microtuble-associated protein 1 light chain 3 |

| MAO-A and -B | type A and B monoamine oxidase |

| Mfn | mitofusion |

| MPT | membrane permeability transition |

| mPTP | mitochondrial permeability transition pore |

| mtDNA | mitochondrial DNA |

| NTF | neurotrophic factor |

| Nrf | nuclear respiratory factor |

| OMM | outer mitochondrial membrane |

| Opa1 | optic atrophy gene1 |

| PGC-1α | peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1-α |

| Smac | second mitochondria-activator of caspases |

| TFAM | mitochondrial transcription factor A |

| TOM | translocase of the outer membrane |

| TSPO | the outer membrane transporter protein (18 kDa) |

| TPP+ | triphenylphosphonium |

| VDAC | voltage-dependent anion channel |

References

- Roger, A.J.; Muniz-Gomez, S.A.; Kamikawa, R. The origin and diversification of mitochondria. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, R1177–R1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariinho, H.S.; Reak, C.; Cyrne, L.; Soares, H.; Antunes, F. Hydrogen peroxide sensing, signaling and regulation of transcription factors. Redox Biol. 2014, 2, 535–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Radi, E.; Formichi, P.; Battisti, C.; Federico, A. Apoptosis and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2014, 42, S125–S152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kroemer, G. Mitochondrial implication in apoptosis. Towards an endosymbiont hypothesis of apoptosis evolution. Cell Death Differ. 1997, 4, 443–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vianello, A.; Casolo, V.; Petrussa, E.; Peresson, C.; Patui, S.; Bertolini, A.; Passamonti, S.; Braidot, E.; Zancani, M. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore (PTP)—An example of multiple molecular exaptation? Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1817, 2072–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Liu, J.; Liu, N.; Kuhn, L.A.; Garavito, R.M.; Ferguson-Miller, S. Translocator protein 18kDa (TSPO): An old protein with new functions? Biochemistry 2016, 55, 2821–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naoi, M.; Maruyama, W.; Yi, H.; Inaba-Hasegawa, K.; Akao, Y.; Shamoto-Nagai, M. Mitochondria in neurodegenerative disorders: Regulation of the redox state and death signaling leading to neural death and survival. J. Neural Transm. 2009, 116, 1371–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaturvedi, R.K.; Beal, M.F. Mitochondrial approaches for neuroprotection. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1147, 395–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naoi, M.; Maruyama, W.; Yi, H. Rasagiline prevents apoptosis induced by PK11195, a ligand of the outer membrane translocator protein (18 kDa), in SH-SY5Y cells through suppression of cytochrome c release from mitochondria. J. Neural Transm. 2013, 120, 1539–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naoi, M.; Maruyama, W.; Inaba-Hasegawa, K. Revelation in neuroprotective functions of rasagiline and selegiline: The induction of distinct genes by different mechanisms. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2013, 13, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Kazumura, K.; Maruyama, W.; Osawa, T.; Naoi, M. Rasagiline and selegiline suppress calcium efflux from mitochondrial by PK11195-induced opening of mitochondrial permeability transition pore: A novel anti-apoptotic function for neuroprotection. J. Neural Transm. 2015, 122, 1399–1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, L.; Partridge, L. Promoting health and longevity through diet: From model organization to humans. Cell 2015, 161, 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, S.; Cassidy, A.; Willett, W.C.; Rimm, E.B.; O’Reilli, E.J.; Okereke, O. Dietary flavonoid intake and risk of incident depression in midlife and older women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2016, 104, 704–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solanski, I.; Parihar, P.; Parihar, M.S. Neurodegenerative diseases: From available treatments to prospective herbal therapy. Neurochem. Int. 2016, 95, 100–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval-Acuna, C.; Ferreira, J.; Speisky, H. Polyphenols and mitochondria: An update on their increasingly emerging ROS-scavenging independent actions. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014, 559, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Shamoto-Nagai, M.; Maruyama, W.; Osawa, T.; Naoi, M. Phytochemicals prevent mitochondrial permeabilization and protect SH-SY5Y cells against apoptosis induced by PK11195, a ligand for outer membrane translocator protein. J. Neural Transm. 2017, 124, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naoi, M.; Inaba-Hasegawa, K.; Shamoto-Nagai, M.; Maruyama, W. Neurotrophic function of phytochemicals for neuroprotection in aging and neurodegenerative disorders: Modulation of intracellular signaling and gene expression. J. Neural Transm. 2017, 124, 1515–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naoi, M.; Shamoto-Nagai, M.; Maruyama, W. Neuroprotection of multifunctional phytochemicals as novel therapeutic strategy for neurodegenerative disorders: Antiapoptotic and antiamyloidogenic activities by modulation of cellular signal pathways. Future Neurol. 2019, 14, FNL9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lustgardern, M.S.; Bhattacharya, A.; Muller, F.L.; Jang, Y.C.; Shimizu, T.; Shirasawa, T.; Richardson, A.; Van Remmen, H. Complex I generated, mitochondrial matrix-directed superoxide is release from the mitochondria through voltage dependent anion channels. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 422, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaidery, N.A.; Thomas, B. Current perspective of mitochondrial biology in Parkinson’s disease. Neurochem. Int. 2018, 117, 91–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicklas, W.J.; Vyas, I.; Heikkila, R.E. Inhibition of NADH-linked oxidation in brain mitochondria by 1-methyl-4-phenyl-pyridine, a metabolite of the neurotoxin, 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,5,6-tetrahydro-pyridine. Life Sci. 1985, 36, 2503–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuno, Y.; Ikebe, S.; Hattori, N.; Nakagawa-Hattori, Y.; Mochizuki, H.; Tanaka, M.; Ozawa, T. Mitochondria in the etiology and pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1995, 1271, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, P.; Reddy, P.H. Aging and amyloid beta-induced oxidative DNA damage and mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: Implications for early intervention and therapeutics. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1812, 1359–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morais, V.A.; De Strooper, B. Mitochondria dysfunction and neurodegenerative disorders: Cause or consequence. J. Alzheimers Dis. 2010, 20, S255–S263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.T.; Cantuti-Castelvetri, I.; Zheng, K.; Jackson, K.E.; Tan, Y.B.; Arzberger, T.; Lees, A.J.; Betensky, R.A.; Bea, M.F.; Simon, D.K. Somatic mitochondrial DNA mutations in early Parkinson’s disease and incidental Lewy body disease. Ann. Neurol. 2012, 71, 850–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thyagarajan, D.; Bressman, S.; Bruno, C.; Przedborski, S.; Shanske, S.; Lynch, T.; Fahn, S.; DiMauro, S. A novel mitochondrial 12SrRNA point mutation in Parkinsonism, deafness, and neuropathy. Ann. Neurol. 2000, 48, 730–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, D.K.; Pulst, S.M.; Sutton, J.P.; Browne, S.E.; Beal, M.F.; Johns, D.R. Familial multisystem degeneration with parkinsonism associated with the 11778 mitochondrial DNA mutation. Neurology 1999, 53, 1787–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoffner, J.M.; Brown, M.D.; Torroni, A.; Lott, M.T.; Cabell, M.F.; Mirra, S.S.; Beal, M.F.; Yang, C.C.; Gearing, M.; Salvo, R.; et al. Mitochondrial DNA variants observed in Alzheimer and Parkinson disease patients. Genomics 1993, 17, 171–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autere, J.; Moilanen, J.S.; Finnilä, S.; Soinien, H.; Mannermaa, A.; Hartttikainen, P.; Hallikainen, M.; Majamaa, K. Mitochondrial DNA polymorphisms as risk factors for Parkinson’s disease and Parkinson’s disease dementia. Hum. Genet. 2004, 115, 29–35. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Zhang, J.; Chunxue, J.; Wang, L. MiR-144-3p and its target gene β-amyloid precursor protein regulate 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. Mol. Cells 2016, 39, 543–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, A.; Desplats, P.; Spencer, B.; Rockenstein, E.; Adame, A.; Elstner, M.; Laub, C.; Mueller, S.; Koob, A.; Mante, M.; et al. TOM40 mediates mitochondrial dysfunction induced by α-synuclein accumulation in Parkinson’s disease. PLoS ONE 2013, 23, e62277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Maio, R.; Barrett, P.J.; Hoffman, E.K.; Barrett, C.W.; Zharikov, A.; Borah, A.; Hu, X.; McCoy, J.; Chu, C.T.; Burton, E.A.; et al. α-Synuclein binds TOM20 and inhibits mitochondrial protein import in Parkinson’s disease. Sci. Transl. Med. 2016, 8, 342–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansson Petersen, C.A.; Alikhani, N.; Behbahan, H.; Wiehager, B.; Pavlov, P.F.; Alafuzoff, I.; Leinonen, V.; Ito, A.; Winblad, B.; Glaser, E.; Ankarcrona, M.; et al. The amyloid beta-peptide is imported into mitochondria via the TOM import machinery and localized to mitochondrial cristae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 13145–13150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manczak, M.; Reddy, P.H. Abnormal interaction of VDAC1 with amyloid beta and phosphorylated tau causes mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2012, 21, 5131–5146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, J.; Du, T.; Wang, X.; Duan, C.; Gao, G.; Zhang, J.; Lu, L.; Yang, H. α-Synuclein amino terminals regulates mitochondrial membrane permeability. Br. Res. 2014, 1591, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostovtseva, T.; Gurney, P.A.; Protchenko, O.; Hoogerheide, D.P.; Yap, T.L.; Philpott, C.C.; Lee, J.C.; Berzrukov, S.M. α-Synuclein shows high affinity interaction with voltage-dependent anion channel, suggesting mechanisms of mitochondrial regulation and toxicity in Parkinson disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 18467–18477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smilansky, A.; Dangoor, L.; Nakdimon, I.; Ben-Hail, D.; Mizrachi, D.; Shoushan-Barmatz, V. The voltage-dependent anion channel1 mediates amyloid β toxicity and represents a potential target for Alzheimer disease therapy. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 30670–30683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reddy, P.H.; Yin, X.; Manczak, M.; Kumar, S.; Pradeepkiran, J.A.; Vijayan, M.; Reddy, A.P. Mutant APP and amyloid beta-induced defective autophagy, mitophagy, mitochondrial structural and functional changes and synaptic damage in hippocampal neurons from Alzheimer’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2018, 27, 2502–2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baines, C.P.; Gutierrez-Aguilar, M. The still uncertain identity of the channel-forming unit(s) of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Cell Calcium 2018, 73, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinopoulos, C. Mitochondrial permeability transition pore: Back to the drawing board. Neurochem. Int. 2018, 117, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alavian, K.N.; Beutner, G.; Lazrove, E.; Sacchetti, S.; Park, H.A.; Licznerski, P.; Li, H.; Nabili, P.; Hockensmith, K.; Graham, M.; Porter, G.A.; Jonas, E.S. An uncoupling channel with the c-subunits ring of F1F0 ATP synthase is the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 10580–10585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernardi, P.; Rasola, A.; Forte, M.; Lippe, G. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore: Channel formation by F-ATP synthase, integration in signal transduction and role in pathophysiology. Physiol. Rev. 2015, 95, 1111–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Commenges, D.; Scotet, V.; Renaud, S.; Jacqmin-Gadda, H.; Barberger-Gateau, P.; Dartigues, J.F. Intake of flavonoids and risk of dementia. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2000, 16, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibellini, L.; Bianchini, E.; De Biasi, A.; Nasi, M.; Cossarizza, A.; Pinti, M. Natural compounds modulating mitochondrial functions. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2015, 2015, ID 527209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solamki, I.; Parihar, P.; Mansuri, M.L.; Parihar, M.S. Flavonoid-based therapies in the early management of neurodegenerative diseases. Adv. Nutr. 2015, 6, 54–72. [Google Scholar]

- De Oliveira, M.R.; Nabavi, S.F.; Manayi, A.; Daglia, M.; Hajheydari, Z.; Nabavi, S.M. Resveratrol and mitochondria: From triggering the intrinsic apoptotic pathway to inducing mitochondrial biogenesis, a mechanistic view. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1860, 727–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramassamy, C. Emerging role of polyphenolic compounds in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases: A review of their intracellular targets. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 545, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandareesh, M.D.; Mythri, R.B.; Srinivas Bharath, M.M. Bioavailability of dietary polyphenols: Factors contributing to their clinical application in CNS diseases. Neurochem. Int. 2015, 89, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, R.D.; Frtz, J.B. Properties of an immortalised vascular endothelial/glioma cell co-culture model of the blood-brain-barrier. J. Cell. Physiol. 1996, 167, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youdim, K.A.; Shukitt-Hale, B.; Joseph, J.A. Flavonoids and the brain: Interactions at the blood-brain-barrier and their physiological effects on the central nervous system. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 2004, 37, 1683–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heim, K.E.; Tagliaferro, A.R.; Bobilya, D.J. Flavonoid antioxidants: Chemistry, metabolism and structure-activity relationship. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2002, 13, 572–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mira, L.; Fernandez, M.T.; Santos, M.; Rocha, R.; Florencio, M.H.; Jennings, K.R. Interaction of flavonoids with iron and copper ions: A mechanism of their antioxidant activity. Free Rad. Res. 2002, 36, 1199–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carradori, S.; Gidaro, M.C.; Petzer, A.; Costa, G.; Guglielmi, P.; Chimenti, P.; Alcaro, S.; Petzer, J.P. Inhibition of human monoamine oxidase: Biological and molecular modeling studies on selected natural flavonoids. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 9004–9011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, N.; Dhiman, P.; Sobarzo-Sanchez, E.; Khatkar, A. Flavonoids and anthranquinones as xanthine oxidase and monoamine oxidase inhibitors: A new approach towards inflammation and oxidative stress. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2018, 18, 2154–2164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefian, M.; Shakour, N.; Hosseinzadeh, H.; Hayes, A.W.; Hadizadeh, F.; Karimi, G. The natural phenolic compounds as modulators of NADH oxidases in hypertension. Phytomedicine 2019, 55, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunnumakkara, A.B.; Bordoloi, D.; Padmavathi, G.; Monisha, J.; Roy, N.K.; Prasad, S.; Aggarwal, B.B. Curcumin, the golden nutraceutical: Multitargeting for multiple chronic diseases. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 1325–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barzegar, A.; Moosavi-Movahedi, A.A. Intracellular ROS protection efficiency and free radical-scavenging activity of curcumin. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e26012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinvasan, M.; Sudheer, A.R.; Menon, V.P. Ferulic acid: Therapeutic potential through its antioxidant property. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2007, 92, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulose, S.M.; Thnagthaeng, N.; Miller, M.G.; Shukitt-Hale, B. Effects of pterostilbene and resveratrol on brain and behavior. Neurochem. Int. 2015, 89, 227–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goto, S.; Kogure, K.; Abe, K.; Kimata, Y.; Kitamura, K.; Yamashita, E.; Terada, H. Efficient radical trapping at the surface and inside the phospholipid membrane is responsible for highly antiperoxidative activity of the carotenoid astaxanthin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2001, 1512, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grougnet, R.; Magiatis, P.; Laborie, H.; Lazarou, D.; Papadopoulos, A.; Skaltsounis, A. Sesaminol glucoside, disaminyl ether, and other lignans from sesame seeds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 60, 108–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, C.M.; Singh, S.A. Bioactive lignans from sesame (Seaamum indicum L.): Evaluation of their antioxidant and antibacterial effects for food applications. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 2934–2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamada, N.; Tanaka, A.; Fujita, Y.; Itoh, T.; Ono, Y.; Kitagawa, Y.; Tomimori, N.; Kiso, Y.; Akao, Y.; Nozawa, Y.; et al. Involvement of heme oxygenase-1 induction via Nrf/ARE activation in protection against H2O2-induced PC12 cell death by a metabolite of sesamin contained in sesame seeds. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2011, 19, 1959–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.; Chen, C.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; Chen, Z.; Yang, C.; Lianf, X.; Zhu, G.; Xu, Z. Neuroprotective effect of curcumin against cerebral ischemia-reperfusion via mediating autophagy and inflammation. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 64, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandhan, A.; Tamilselvam, K.; Radhiga, T.; Rao, S.; Essa, M.M.; Manivasagam, T. Theaflavin, a black tea polyphenol, protects nigral dopaminergic neurons against chronic MPTP/probenecid induced Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res. 2012, 1433, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bounival, J.; Quessy, P.; Martinoli, M.G. Protective effects of resveratrol and quercetin against MPP+-induced oxidative stress act by modulating markers of apoptotic death in dopaminergic neurons. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2009, 29, 1169–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alberdi, E.; Sanchez-Gomez, M.V.; Ruiz, A.; Cavaliere, F.; Ortiz-Sanz, C.; Quintela-Lopez, T.; Capetillo-Zarate, E.; Sole-Domenech, S.; Matute, C. Manigiferin and morin attenuate oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and neurocytotoxicity, induced by amyloid beta oligomers. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, ID 2856063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camilleri, A.; Zarb, C.; Caruna, M.; Ostermeier, U.; Ghio, S.; Högen, T.; Schmidt, F.; Giese, A.; Vassallo, N. Mitochondrial membrane permeabilization by amyloid aggregates and protection by polyphenols. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1828, 2532–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.M.; Li, S.Q.; Zhu, X.Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, W.L.; Zhang, X.J. Protective effects of hesperidin against amyloid-β (A β) induced neurotoxicity though the voltage dependent anion channel 1 (VDAC)-mediated mitochondrial apoptotic pathway in PC12 cells. Neurochem. Res. 2013, 38, 1034–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghaffari, H.; Venkataramana, M.; Jalali Ghassam, B.; Chandra Nayaka, S.; Nataraju, A.; Geetha, N.P.; Prakash, H.S. Rosmarinic acid mediates neuroprotective effects against H2O2-induced neuronal cell damage in N2A cells. Life Sci. 2014, 113, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Chen, W.; Fu, X.; Ma, J.; Wang, M.; Hou, Y.; Tian, D.; Fu, X.; Fan, C. Reversal of homocysteine-induced neurotoxicity in rat hippocampal neurons by astaxanthin: Evidences for mitochondrial dysfunction and signaling crosstalk. Cell Death Discov. 2018, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Shamoto-Nagai, M.; Maruyama, W.; Osawa, T.; Naoi, M. Rasagiline prevents cyclosporine A-sensitive superoxide flashes induced by PK11195, the initial signal of mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and apoptosis. J. Neural Transm. 2016, 123, 491–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Serafim, T.L.; Carvalho, F.S.; Marques, M.P.; Calheiros, R.; Silva, T.; Garrido, J.; Milhazes, M.; Borges, F.; Roleira, F.; Silva, E.; et al. Lipophilic caffeic and ferulic acid derivatives presenting cytotoxicity against human breast cancer cells. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2011, 24, 763–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tewari, D.; Ahmed, T.; Chrirasani, V.R.; Singh, P.K.; Maji, S.M.; Senapati, S.; Bera, A.K. Modulation of the mitochondrial voltage dependent anion channel (VDAC) by curcumin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1848, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tong, Z.; Xie, Y.; He, M.; Ma, W.; Zhou, Y.; Lai, S.; Meng, Y.; Liao, Z. VDAC1 deacetylation is involved in the protective effects of resveratrol against mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in cardiomyocytes subjected to anoxia/reoxygenation injury. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 95, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, M.; Xie, Y.; Meng, Y.; Ma, W.; Tong, Z.; Yang, X.; Lai, S.; Zhou, Y.; He, M.; Liao, Z. Resveratrol protects cardiomyocytes against anoxia/reoxygenation via dephosphorylation of VDAC1 by Akt-GSK3 β pathway. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2019, 843, 80–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, B.A.; Oliveira, P.J.; Cristovao, A.; Dias, A.C.; Malva, J.O. Biapigenin modulates the activity of the adenine nucleotide translocator in isolated rat brain mitochondria. Neurotox. Res. 2010, 17, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forbes-Hernandez, T.; Giampieri, F.; Gasparrini, M.; Mazzoni, L.; Quilees, J.L.; Alvarez-Suarez, J.M.; Battino, M. The effects of bioactive compounds from plant foods on mitochondrial function: A focus on apoptotic mechanism. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2014, 68, 154–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.A.; Hou, X.; Hao, S. Mitochondrial biogenesis in neurodegeneration. J. Neurosci. Res. 2017, 95, 2025–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villena, J.A. New insight into PGC-1 coactivators: Their role in the regulation of mitochondrial function and beyond. FEBS J. 2014, 282, 647–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, J.; Deus, C.M.; Borges, F.; Oliveira, P. Mitochondria: Targeting mitochondrial reactive oxygen species with mitochondriotropic polyphenolic-based antioxidants. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2018, 97, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lagouge, M.; Argann, C.; Gerhart-Hines, Z.; Meziane, H.; Lerin, C.; Daussin, F.; Messadeq, N.; Milne, J.; Lambert, P.; Elliott, P.; et al. Resveratrol improved mitochondrial functions against metabolic disease by activating SIRT1 and PGC-1α. Cell 2006, 127, 1109–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.J.; Ahmad, F.; Philp, A.; Baar, K.; Williams, T.; Luo, H.; Ke, H.; Rehmann, H.; Taussig, R.; Brown, A.L.; et al. Resveratrol ameliorates aging-related metabolic phenotypes by inhibiting cAMP phosphodiesterases. Cell 2012, 148, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris-Blanco, K.C.; Cohan, C.H.; Neumann, J.T.; Sick, T.J.; Perez-Pinzon, M.A. Protein kinase C epsilon regulates mitochondrial pools of Nampt and NAD following resveratrol and ischemic preconditioning in the rat cortex. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2014, 34, 1024–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Valenti, D.; De Rasmo, D.; Signorile, A.; Rossi, L.; de Bari, L.; Scala, I.; Granse, B.; Papa, S.; Vacca, R.A. Epigalocatchin-3-gallate prevents oxidative phosphorylation deficit and promotes mitochondrial biogenesis in human cells from subjects with Down’s syndrome. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1832, 542–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos Santos, T.W.; Pereira, Q.C.; Teixeira, L.; Gambero, A.; Villena, J.A.; Ribeiro, M.L. Effects of polyphenols on thermogenesis and mitochondrial biogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasbach, K.A.; Schnellmann, R.G. Isoflavones promote mitochondrial biogenesis. J. Pharm. Exper. Ther. 2019, 368, 536–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Wang, X.; Hou, C.; Yang, L.; Li, H.; Guo, J.; Huo, C.; Wang, M.; Miao, Y.; Liu, J.; et al. Oleuropein improves mitochondrial function to attenuate oxidative stress by activating the Nrf2 pathway in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Neurophamacology 2017, 113 Pt A, 556–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieman, D.C.; Williams, A.S.; Shanely, R.A.; Jin, F.; McAnulty, S.R.; Triplett, N.T.; Austin, M.D.; Henson, D.A. Quercetin’s influence on exercise performance and muscle mitochondrial biogenesis. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2010, 42, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taub, P.R.; Ramirez-Sanchez, I.; Ciaraldi, T.P.; Perkins, G.; Murphy, A.N.; Naviaux, R.; Hogan, M.; Maisel, A.S.; Henry, R.R.; Ceballos, G.; et al. Alterations in skeletal muscle indicators of mitochondrial structure and biogenesis in patients with type 2 diabetes and heart failure: Effects of epicatechin rich cocoa. Clin. Trans. Sci. 2012, 5, 43–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taub, P.R.; Ramairez-Sanchez, I.; Patel, M.; Higginbotham, E.; Taub, P. Beneficial effects of dark chocolate on exercise capacity in sedentary subjects: Underlying mechanisms. Food Funct. 2016, 7, 3686–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Franco-Iborra, S.; Vila, M.; Perier, C. Mitochondrial quality control in neurodegenerative diseases: Focus on Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, D.; Zorzano, A. Mitochondrial dynamics and metabolic homeostasis. Curr. Opin. Physiol. 2018, 3, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Züchner, S.; Mersiyanowa, I.V.; Muglia, M.; Tadmouri, N.B.; Rochelle, J.; Dadali, E.L.; Zappia, M.; Nelis, E.; Patitucci, A.; Senderek, J.; Parman, Y.; Evgrafov, O.; De Jonghe, P.; et al. Mutations in the mitochondrial GTPase mitofusin 2 cause Charcot-Marie-Tooth neuropathy type 2A. Nat. Genet. 2004, 36, 449–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bagli, E.; Zikou, A.K.; Agantis, N.; Kitsos, G. Mitochondrial membrane dynamics and inherited optical neuropathies. In Vivo 2017, 31, 511–525. [Google Scholar]

- Loson, O.C.; Song, Z.; Chen, H.; Chan, D.C. Fis1, Mff, MiD49 and MiD51 mediate Drp1 recruitment in mitochondrial fission. Mol. Biol. Cell 2013, 24, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterham, H.R.; Koster, J.; van Rosermubd, C.W.; Mooyer, P.; Wanders, R.J.; Leonard, J.V. A lethal defect of mitochondrial and peroxisomal fission. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 1736–1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Oliveira, M.R.; Jardim, F.R.; Setzer, W.N.; Nabavi, S.M.; Nabavi, S.F. Curcumin, mitochondrial biogenesis, and mitophagy: Exploring recent data and indicating future needs. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016, 34, 813–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, K.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Ye, F.; Dan, G.; Zhao, Y.; Cai, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wu, Q.; et al. Resveratrol regulates mitochondrial biogenesis and fission/fusion to attenuate rotenone-induced neurotoxicity. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 6705621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palomera-Avalos, V.; Grinan-Ferre, C.; Puigoriol-Ilamola, D.; Camins, A.; Sanfeliu, C.; Canudas, A.M.; Pallas, M. Resveratrol protects SAMP8 brain under metabolic stress: Focus on mitochondrial function and Wnt pathway. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 1661–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Mitrovsky, G.; Vaanthi, H.; Das, D.K. Antiaging properties of a grape-derived antioxidant are regulated by mitochondrial balance of fission and fission leading to mitophagy triggered by a signaling network of Sirt1-Sirt3-Foxo3-Pink1-Parkin. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2014, 2014, ID 345105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrado-Fernandez, C.; Sandebring-Matton, A.; Rodriguez-Rodriguez, P.; Aarsland, D.; Cedazo-Minguez, A. Anthocyanins protect from complex I inhibition and APPswe mutation through modulation of the mitochondrial fission/fusion pathway. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1862, 2110–2118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelsy, N.; Hulick, W.; Winter, A.; Ross, E.; Liseman, D. Neuroprotective effects of anthocyanins on apoptosis induced by mitochondrial oxidative stress. Nutr. Neurosci. 2011, 14, 249–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Mao, P.; Wang, J.; Wang, T.; Xie, C.-H. Allicin protects PC12 cells against 6-OHDA-induced oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction via regulation mitochondrial dynamics. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 36, 966–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lionaki, E.; Markaki, M.; Palikaras, K.; Tavernarakis, N. Mitochondria, autophagy and age-associated neurodegenerative diseases: New insights into a complex interplay. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2015, 1847, 1412–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- East, D.A.; Campanella, M. Mitophagy and therapeutic clearance of damaged mitochondria for neuroprotection. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2016, 79, 382–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, Y.; Yao, Z.; Klionsky, D.J. How to control self-digestion: Transcriptional, post-transcriptional, and post-translational regulation of autophagy. Trends Cell Biol. 2015, 25, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fivenson, E.M.; Lautrup, S.; Sun, N.; Scheibye-Knudsen, M.; Stevnsner, T.; Nilsen, H.; Bohr, V.A.; Fang, E.F. Mitophagy in neurodegeneration and aging. Neurochem. Int. 2017, 109, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodger, C.E.; McWilliams, T.G.; Ganley, I.G. Mammalian mitophagy—From in vitro molecules to in vivo models. FEBS J. 2017, 285, 1185–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, T.; Okamoto, K.; Omiya, S.; Taneike, M.; Yamaguchi, O.; Otsu, K. A mammalian mitophagy receptor, Bcl2-L-13, recruits the ULK complex to induce mitophagy. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 338–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duncan, T.M.; Fon, E.A. The three ‘P’s of mitophagy: PARKIN, PINK1, and post-translational modification. Genes Dev. 2015, 29, 989–999. [Google Scholar]

- Koentjoro, B.; Park, J.-S.; Sue, C.M. Nix restores mitophagy and mitochondrial function to protect against PINK1/Parkin-related Parkinson’s disease. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lin, C.Y.; Tsai, C.W. PINK1/parkin-mediated mitophagy is related to neuroprotection by carnosic acid in SH-SH5Y cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 125, 430–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, A. Modulation of protein quality control systems by food phytochemicals. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2013, 52, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Yang, C.B.; Malampati, S.; Huang, Y.; Li, M.; Li, M.; Sog, J. Neuroprotective natural products for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease by targeting the autophagy-lysosome pathway: A systematic review. Phytother. Res. 2017, 31, 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasima, N.; Ozpolat, S. Regulation of autophagy by polyphenolic compounds as potential therapeutic strategy for cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2014, 5, e1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Teng, Z.; Zhang, T.; Li, Y. Downregulation of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in curcumin-induced autophagy in APP/PS1 double transgenic mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 740, 312–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Zhang, V.; Zhou, H.; Wang, H.; Tian, L.; Liu, J.; Ding, J.; Chen, S. Curcumin ameliorates the neurodegenerative pathology in A5T-synuclein cell model of Parkinson’s disease through the downregulation of mTOR/p70S6K signaling and recovery of macroautophagy. J. Neuroimume Pharmacol. 2013, 8, 356–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaroonwitchawan, T.; Chaicharoenaudomrung, N.; Namkaew, J.; Noisa, P. Curcumin attenuates paraquat-induced cell death in human neuroblastoma cells through modulating oxidative stress and autophagy. Neurosci. Lett. 2017, 616, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossi, C.; Rigacci, S.; Ambrosini, S.; Dami, T.E.; Luccarini, I.; Traini, C.; Failli, P.; Berti, A.; Casamenti, F.; Stefani, M. The polyphenol oleuropein aglycone protects TGCRND6 mice against Aβ plaque pathology. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantano, D.; Luccarini, H.; Nardiello, P.; Servili, M.; Stefani, M. Oleuropein aglycone and polyphenols from olive mill waste water ameliorate cognitive deficits and neuropathology. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2017, 83, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cordero, J.G.; Garcia-Escudero, R.; Avila, J.; Gargini, R.; Garcia-Escudero, V. Benefit of oleuropein aglycone for Alzheimer’s disease by promoting autophagy. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 5010741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Cui, C.; Sun, M.; Zhu, Y.L.; Chu, M.; Shi, Y.W.; Lin, S.L.; Yang, X.S.; Shen, Y.Q. Neuroprotective effects of loganin on MPTP-induced Parkinson’s disease mice: Neurochemistry, glial reaction and autophagy studies. J. Cell. Biochem. 2017, 118, 3495–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filomeni, G.; Graziani, I.; De Zio, D.; Dini, L.; Gentonze, D.; Rotilio, G.; Ciriolo, M.R. Neuroprotection of kaempferol by autophagy in models of rotenone-mediated acute toxicity: Possible implications for Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2012, 33, 767–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holczer, M.; Besze, B.; Zambo, V.; Csala, M.; Banhegyi, G.; Kapuy, O. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) promotes autophagy-dependent survival via influencing the balance of mTOR-AMPA pathways upon endoplasmic reticulum stress. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2018, 2018, 6721530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marambaud, P.; Zhao, H.; Davies, P. Resveratrol promotes clearance of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid-beta peptides. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 37377–37382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vingtdeux, V.; Giliberto, L.; Zhao, H.; Chandakkar, P.; Wu, Q.; Simon, J.E.; Janle, E.M.; Lobo, J.; Ferruzzi, M.G.; Davies, P.; et al. AMP-activated protein kinase signaling activation by resveratrol modulates amyloid-beta peptide metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 9100–9113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Dong, S.; Cui, X.; Feng, Y.; Liu, T.; Yin, M.; Kuo, S.H.; Tan, E.K.; Zhao, W.J.; et al. Resveratrol alleviates MPTP-induced motor impairments and pathological changes by autophagic degradation of α−synuclein via SIRT1-deacetylated LC3. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2016, 60, 2161–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, D.; Jeong, H.; Lee, M.; Koh, A.; Kwon, O.; Yang, Y.; Noh, J.; Suh, P.; Park, H.; Ryu, S. Resveratrol induces autophagy by directly inhibiting mTOR through ATP competition. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.; Moon, J.; Kim, S.; Jeong, J.; Nazim, U.; Lee, Y.; Seol, J.; Park, S. EGCG-mediated autophagy flux has a neuroprotection effect via a class III histone deacetylase in primary neuron cells. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 9701–9717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Caruana, M.; Högen, T.; Levin, J.; Hillmer, A.; Giese, A.; Vassallo, N. Inhibition and disaggregation of α-synuclein oligomers by natural polyphenol compounds. FEBS Lett. 2011, 585, 1113–1120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grelle, G.; Otto, A.; Lorenz, M.; Frank, R.F.; Wanker, E.; Bieschke, J. Black tea theaflavins inhibit formation of toxic amyloid-β and α-synuclein fibrils. Biochemistry 2011, 50, 10624–10636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andich, K. The effect of (-)-epigallo-catechin-(3)-gallate on amyloidogenic proteins suggests a common mechanism. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2015, 863, 139–161. [Google Scholar]

- Ngougoure, V.L.N.; Schuesener, J.; Moundipa, P.F.; Schluesener, H. Natural polyphenols binding to amyloid: A broad class of compounds to treat different human amyloid diseases. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2015, 59, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Uversky, V.N.; Huang, M.; Kang, H.; Xu, F.; Liu, X.; Lian, L.; Liang, Q.; Jiang, H.; Liu, A.; et al. Baicalein inhibits α-synuclein oligomer formation and prevents progression of α-synuclein accumulation in a rotenone mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1862, 1883–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thapa, A.; Jett, S.D.; Chi, E.Y. Curcumin attenuates amyloid-β aggregate toxicity and modulates amyloid-β aggregation pathway. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2016, 7, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsch, D.T.; Das, S.; Ridell, J.; Smid, S.D. Structure-activity relationships for flavone interactions with amyloid β reveal a novel anti-aggregatory and neuroprotective effects of 2′,3′,4′-trihydroxyflavone (2-D08). Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2017, 25, 3827–3834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neuzil, J.; Dong, L.F.; Rohlena, J.; Truksa, J.; Ralph, S.J. Classification of mitocans, anticancer drugs acting on mitochondria. Mitochondrion 2013, 13, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorlach, S.; Fichna, J.; Lewandiwska, U. Polyphenols as mitochondria-targeted anticancer drugs. Cancer Lett. 2015, 336, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pistollato, F.; Giampieri, F.; Battino, M. The use of plant-derived bioactive compounds to target cancer stem cells and modulate tumor microenvironment. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2015, 75, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zheng, J.; Li, Y.; Xu, D.P.; Li, S.; Che, Y.M.; Li, H.B. Natural polyphenols for prevention and treatment of cancer. Nutrients 2016, 8, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Yi, T.; Liu, J.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, H. Quercetin induces apoptosis via the mitochondrial pathway in KB and KBv200 cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 2188–2195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, Y.; Yu, T.; Wang, W.; Pan, K.; Shi, D.; Sun, H. Curcumin-induced melanoma cell death is associated with mitochondrial permeability transition pore (mPTP) opening. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 448, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oishi, M.; Iizumi, Y.; Taniguchi, T.; Goi, W.; Miki, T.; Sakai, T. Apigenin sensitizes prostate cancer cells to Apo2L/TRAIL by targeting adenine nucleotide translocator-2. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sassi, N.; Mattarei, A.; Azzolini, M.; Szabo, I.; Paradisi, C.; Zoratti, M.; Biasutto, L. Cytotoxicity of mitochondria-targeted resveratrol derivatives: Interactions with respiratory chain complexes and ATP synthase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1837, 1781–1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gueguen, N.; Desquiret-Dumas, V.; Leman, G.; Chupin, S.; Baron, S.; Nivet-Antoine, V.; Vessières, E.; Ayer, A.; Henrion, D.; Lenaers, G.; et al. Resveratrol directly binds to mitochondrial complex I and increases oxidative stress in brain mitochondria of aged mice. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madrigal-Perz, L.A.; Ramos-Gomez, M. Resveratrol inhibition of cellular respiration: New paradigm for an old mechanism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valenti, D.; de Bari, L.; Manente, G.A.; Rossi, L.; Mutti, L.; Moro, L.; Vacca, R.A. Negative modulation of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation by epigallocatechin-3 gallate leads to growth arrest and apoptosis in human malignant pleural mesothelioma cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2013, 1832, 2085–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, B.; Chu, W.; Wei, P.; Liu, Y.; Wei, T. Xanthohumol induces generation of reactive oxygen species and triggers apoptosis through inhibition of mitochondrial electron transfer chain complex I. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015, 89, 486–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabarwal, A.; Agarwal, R.; Sigh, R.P. Fisetin inhibits cellular proliferation and induces mitochondria-dependent apoptosis in human gastric cancer cells. Mol. Carcinog. 2017, 56, 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvi, M.; Brunati, A.M.; Clari, G.; Toninello, A. Interaction of genistein with the mitochondrial electron transport chain results in opening of the membrane transition pore. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2002, 1556, 187–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Salimi, A.; Roudkenar, M.H.; Seydi, E.; Sadeghi, L.; Mohseni, A.; Pirahmadi, N.; Pourahmad, J. Chrysin as an anti-cancer agent exerts selective toxicity by directly inhibiting mitochondrial complex II and V in CLL B-lymphocytes. Cancer Investig. 2017, 35, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, M.; Zhai, D.; Sareth, S.; Kitada, S.; Reed, J.C.; Pellecchia, M. Cancer prevention by tea polyphenols is linked to their direct inhibition of antiapoptotic Bcl-2-family protein. Cancer Res. 2003, 63, 8118–8121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Benvenuto, M.; Mattera, R.; Sticca, J.I.; Rossi, P.; Cipriani, C.; Giganti, M.G.; Volpi, A.; Modesti, A.; Masuelli, L.; Bei1, R. Effect of the BH3 polyphenol (-)-gossypol (AT-101) on the in vitro and in vivo growth of malignant mesothelioma. Front. Pharm. 2018, 9, 1269. [Google Scholar]

- Song, X.D.; Zhang, J.J.; Wang, M.R.; Liu, W.B.; Gu, X.B.; Lv, C. Astaxanthin induces mitochondria-mediated apoptosis in rat hepatocellular carcinoma CBRH-7919 cells. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2011, 34, 839–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mou, S.; Zhou, Z.; He, Y.; Liu, F.; Gong, L. Curcumin inhibits cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis of larygeal cancer cells through Bcl-2 and PI3K/Akt, and by upregulation miR-12a. Oncol. Lett. 2017, 14, 4937–4942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Fan, H.; Chen, Q.; Ma, G.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, J. Curcumin inhibits aerobic glycolysis and induces mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis through hexokinase II in human colorectal cancer cells in vitro. Anticancer Drugs 2015, 26, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Zhou, Y.; Dai, Q.; Qiao, C.; Zhao, L.; Hui, H.; Lu, N.; Guo, Q.L. Oroxylin A induces dissociation of hexokinase II from the mitochondrial and inhibits glycolysis by SIRT3-mediated deacetylation of cyclophilin D in breast carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2013, 18, e601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomez, L.S.; Zancan, P.; Marocondes, M.C.; Ramos-Santos, L.; Meyer-Fernandes, J.R.; Sola-Penna, M.; Da Silva, D. Resveratrol decreases breast cancer viability and glucose metabolism by inhibiting 6-phosphofructo-1-kinase. Biochimie 2013, 95, 1336–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, K.; Lee, J.; Quach, C.; Pik, J.; Oh, H.; Park, J.; Lee, E.; Moon, S.; Lee, K. Resveratrol suppresses cancer cell glucose uptake by targeting reactive oxygen species-mediated hypoxia-inducible factor-1α activation. J. Nucl. Med. 2013, 54, 2161–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Ruan, Y.; Chen, Q.; Li, S.; Wang, Q.; Cai, J. Curcumin induced HepG2 cell apoptosis-associated mitochondrial membrane potential and intracellular free Ca2+ concentration. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2011, 650, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, W.Z.; Chou, C.T.; Chang, H.T.; Cheng, J.S.; Kuo, D.H.; Ko, K.C.; Chiang, N.N.; Wu, R.F.; Shieh, P.; Jan, C.R. The mechanism of honokiol-induced intracellular Ca2+ rises and apoptosis in human glioblastoma cells. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2014, 221, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, W.Z.; Chou, C.T.; Hsu, S.S.; Liao, W.C.; Shieh, P.; Kuo, D.H.; Tseng, H.W.; Kuo, C.C.; Jan, C.R. The involvement of mitochondrial apoptotic pathway in eugenol-induced cell death in human glioblastoma cells. Toxicol. Lett. 2015, 232, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.T.; Chou, C.T.; Kuo, D.H.; Shieh, P.; Liang, W.Z. The mechanism of Ca2+ movement in the involvement of baicalein-induced cytotoxicity in ZR-75-1 human breast cancer cells. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 1624–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, J.; Li, R.; Zhao, X.; Ma, C.; Lv, X.; Liu, L.; Liu, P. Morusin induced paraptosis-like cell death through mitochondrial calcium overload and dysfunction in epithelial ovarian cancer. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2018, 283, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchetti, C.; Ribulla, S.; Magnelli, V.; Patrone, M.; Burlando, B. Resveratrol induces intracellular Ca2+ rise via T-type Ca2+ channels in a mesothelioma cell line. Life Sci. 2016, 148, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosavi, M.A.; Haghi, A.; Rahmati, M.; Taniguchi, H.; Mocan, A.; Echeverria, J.; Gupta, V.; Tzvertkov, N.; Atamasov, A. Phytochemicals as potent modulators of autophagy for cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2018, 424, 46–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aryal, P.; Kim, K.; Park, P.H.; Ham, S.; Cho, J.; Song, K. Baicalein induces autophagic cell death through AMPK/ULK1 activation and downregulation of mTORC1 complex components in human cancer cells. FEBS J. 2014, 281, 4644–4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhao, L.; Liu, S.; Xu, J.; Li, W.; Duan, G.; Wang, H.; Yang, H.; Yang, H.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, R. A new molecular mechanism underlying the EGCG-mediated autophagic modulation of AFP in HepG2 cells. Cell Death Dis. 2017, 8, e3160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wu, H.; Wang, Y.; Wu, C.; Yang, P.; Li, H.; Li, Z. Resveratrol induces cancer cell apoptosis through MiR-326/PKM2-mediated ER stress and mitochondrial fission. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 9356–9367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zielonka, J.; Joseph, J.; Sikora, A.; Hardy, M.; Ouari, O.; Vasquez-Vivar, J.; Cheng, G.; Lopez, M.; Kalyanaraman, B. Mitochondria-targeted triphenylphosphonium-based compounds: Syntheses, mechanisms of action, and therapeutic and diagnostic applications. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 10043–10120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biasutto, L.; Mattarei, A.; Marotta, E.; Bradaschia, A.; Sassi, N.; Garbisa, S.; Zoratti, M.; Paradisi, C. Development of mitochondria-targeted derivatives of resveratrol. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 18, 5594–5597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.-W.; Xu, X.-C.; Liu, T.; Yuan, S. Mitochondrion-permeable antioxidants to treat ROS-burst-mediated acute disease. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, ID 6859523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattarei, A.; Biasutto, L.; Marotta, E.; De Marchi, U. A mitochondriotropic derivatives of quercetin: A strategy to increase the effectiveness of polyphenols. Chembiochem 2008, 9, 2633–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teixeira, J.; Cagide, F.; Benfeito, S.; Soares, P.; Garrido, J.; Baldeiras, I.; Ribeiro, J.A.; Pereira, C.M.; Silva, A.F.; Andrade, P.B.; et al. Development of a mitochondriotropic antioxidant based on caffeic acid: Proof of concept on cellar and mitochondrial oxidative stress models. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 7084–7098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, C.; Benfeito, S.; Amorim, R.; Teixeira, J.; Oliveira, P.J.; Remiao, F.; Borges, F. Desrisking the cytotoxicity of a mitochondriotropic antioxidant based on caffeic acid by a PEGlated strategy. Bioconjug. Chem. 2018, 29, 2723–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Nagappan, G.; Guan, X.; Nathan, P.J.; Wren, P. BDNF-based synaptic repair as a disease-modifying strategy for neurodegenerative diseases. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013, 14, 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campos-Bedolla, P.; Walter, F.R.; Veszelka, S.; Deli, M.A. Role of the blood-brain-barrier in the nutrition of the central nervous system. Arch. Med. Res. 2014, 45, 610–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelbrecht, I.; Petzer, J.P.; Petzer, A. The synthesis and evaluation of sesamol and benzodioxane derivatives as inhibitors of monoamine oxidase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 25, 1896–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badavath, V.N.; Baysal, I.; Ulcar, G.; Sinha, B.N.; Jayaprakash, V. Monoamine oxidase inhibitory activity of novel pyrazoline analogues curcumin-based design and synthesis. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, E.; Hu, K.; Bai, P.; Yu, L.; Ma, P.; Li, T.; Zhang, X.; Chen, C.; Peng, K.; Liu, W. Design, synthesis and evaluation of novel ferulic acid-maroquin hybrids as potential multifunctional agents for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016, 26, 2539–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Qiang, X.; Luo, L.; Yang, X.; Xiao, G.; Zheng, Y.; Cao, Z.; Sang, Z.; Su, F.; Deng, Y. Multitarget drug design strategy against Alzheimer’s disease: Homoisoflavonoid Mannich base derivatives serve as acetylcholinesterase and monoamine oxidase B dual inhibitors with multifunctional properties. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2017, 25, 714–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiang, X.; Sang, Z.; Yuan, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, Q.; Bai, P.; Shi, Y.; Ang, W.; Tan, Z.; Deng, Y. Design, synthesis and evaluation of genistein-O-alkylbenzylaines as potential multifunctional agents for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 76, 314–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayaraji, R.; Elangovan, N.; Dhanalakshmi, C.; Manivasagam, T.; Essa, M.M. CNB-001, a novel pyrazole derivative mitigates motor impairments associated with neurodegeneration via suppression of neuroinflammatory and apoptotic response in experimental Parkinson’s disease mice. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2014, 229, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasutto, L.; Mattarei, A.; Azzolini, M.; La Spina, M.; Sassi, N.; Romio, M.; Paradisi, C.; Zoratti, M. Resveratrol derivatives as a pharmacological tool. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2017, 1403, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsepaeva, O.; Nemtarev, A.V.; Abdullin, T.I.; Brigor’eva, L.R.; Kuznetsova, E.V.; Akhmadishina, R.A.; Ziganshina, L.E.; Cong, H.H.; Mironov, V.F. Design, synthesis, and cancer cell growth inhibitory activity of triphenylphosphonium derivatives of the triterpenoid betulin. J. Nat. Prod. 2017, 80, 2232–2239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattarei, A.; Roio, M.; Manago, A.; Zoratti, M.; Paradis, C.; Szabo, I.; Leanza, L.; Biasutto, L. Novel-mitochondria-targeted furocoumarin derivatives as possible anti-cancer agents. Front. Oncol. 2018, 6, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueira, I.; Garcia, G.; Pimpao, R.C.; Terrasso, A.P.; Costa, I.; Almeida, A.F.; Tavares, L.; Pais, T.F.; Pinto, P.; Ventura, M.R.; et al. Polyphenols journey through blood-brain barrier towards neuronal protection. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lambert, J.D.; Sang, S.; Yang, C.S. Possible controversy over dietary polyphenols: Benefits vs. risks. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2007, 20, 583–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeikaite-Ceniene, A.; Imbrasaite, A.; Sergediene, E.; Cebas, N. Quantitative structure-activity relationships in prooxidant cytotoxicity of polyphenols: Role of potential of phenoxy radical/phenol redox couple. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2005, 44, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, K.O.; Chan, S.; Pang, C.P.; Wang, C.C. Pro-oxidative and antioxidative controls and signaling modification of polyphenolic phytochemicals: Contribution to health promotion and disease prevention? J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 4026–4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madreiter-Sokolowski, C.T.; Sokolowski, A.A.; Graier, W.F. Dosis Facit Sanitatem–Concentration-dependent effects of resveratrol on mitochondria. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marchi, U.; Biasutto, L.; Garbisa, S.; Toninello, A.; Zoratti, M. Quercetin can act either as an inhibitor or an inducer of mitochondrial permeability transition pore: A demonstration of the ambivalent redox character of polyphenols. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2009, 1787, 1425–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, D.; Barthelemy, S.; Zini, R.; Labidalle, S.; Tillement, J.P. Curcumin induces the mitochondrial permeability transition pore mediated by membrane protein thiol oxidation. FEBS Lett. 2001, 495, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Selassie, C.D.; Kpur, S.; Verma, R.R.; Rosario, M. Cellular apoptosis and cytotoxicity of phenolic compounds: A quantitative structure-activity relationship study. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 7234–7242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Lin, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Xia, Q.; Zhu, B.; Lin, Z. 3D-QSAR studies on caspase-mediated apoptosis activity of phenolic analogues. J. Mol. Model. 2011, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyake, T.; Yasukawa, K.; Inoue, K. Analysis of the mechanism of inhibition of human matrix metalloprotease 7 (MMP-7) activity by green tea catechins. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2011, 75, 1564–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, W.; Wang, Q.; Sun, D.; Suo, J. Curcumin suppresses colon cancer cell invasion via AMPK-induced inhibition of NF-κB, uPA activator and MMP9. Oncol. Lett. 2016, 12, 413904146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansuri, M.L.; Parihar, P.; Solanki, I.; Parihar, M.S. Flavonoids in modulation of cell survival signaling pathways. Genes Nutr. 2014, 9, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Hussain, T.; Mukhtar, H. Molecular pathway for (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate-induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis of human prostate carcinoma cells. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2003, 410, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Lung, W.; Xie, C.; Luo, X.; Huang, W. EGCG inhibited bladder cancer T24 and 5637 cell proliferation and migration via PI3K/AKT pathway. Oncotarget 2018, 9, 12261–12272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lian, H.; Zheng, H. Signaling pathways regulating neuron-glia interaction and their implications in Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2016, 136, 475–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roma-Rodrigues, C.; Medes, R.; Baptista, P.V.; Fernandes, A.R. Targeting tumor microenvironment for cancer therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moosavi, F.; Hosseini, R.; Saso, L.; Firuzi, O. Modulation of neurotrophic signaling pathways by polyphenols. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2016, 10, 23–42. [Google Scholar]

- Baarine, M.; Thandapilly, S.J.; Louis, X.L.; Mazue, F.; Yu, L.; Delmas, D.; Nettucadan, T.; Lizard, G.; Latruffe, N. Pro-apoptotic versus anti-apoptotic properties of dietary resveratrol on tumoral and normal cardiac cells. Genes Nutr. 2011, 6, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Han, Y.; Jo, H.; Cho, J.H.; Dhanasekaran, D.N.; Song, Y.S. Resveratrol as a tumor-suppressive nutraceutical modulating tumor microenvironment and malignant behaviors of cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ||||||||

| Flavonols | ||||||||

| Name | 3 | 5 | 7 | 2′ | 3′ | 4′ | 5′ | |

| Datiscetin | H | OH | OH | OH | H | H | H | |

| Fisetin | H | H | OH | H | OH | OH | H | |

| Galangin | H | OH | OH | H | H | H | H | |

| Kaempferol | H | OH | OH | H | H | OH | H | |

| Morin | H | OH | OH | OH | H | OH | H | |

| Myricetin | H | OH | OH | H | OH | OH | OH | |

| Quercetin | H | OH | OH | H | OH | OH | H | |

| Rutin | ORu * | OH | OH | OH | OH | OH | H | |

| Flavanols | ||||||||

| Name | 3 | 5′ | ||||||

| Catechin | H | H | ||||||

| EGC | H | OH | ||||||

| EGC | H | OH | ||||||

| EGCG | Gallate | OH | ||||||

| Flavones | ||||||||

| Name | 6 | 8 | 3′ | 4′ | ||||

| Acacetin | H | H | H | OCH3 | ||||

| Apigenin | H | H | H | OH | ||||

| Baicalein | OH | H | H | H | ||||

| Chrysin | H | H | H | H | ||||

| Eupafolin | OCH3 | H | OH | OH | ||||

| Hispidulin | OCH3 | H | H | OH | ||||

| Luteolin | H | H | OH | OH | ||||

| Oroxylin A | OCH3 | H | H | H | ||||

| Wogonin | H | OCH3 | H | H | ||||

| Isoflavones | ||||||||

| Name | 5 | 7 | 3′ | 4′ | ||||

| Biochanin A | OH | OH | H | OCH3 | ||||

| Daidzein | H | OH | OH | H | ||||

| Formononetin | H | H | OCH3 | H | ||||

| Genistein | OH | H | OH | H | ||||

| Flavanones | ||||||||

| Name | 7 | 3′ | 4′ | |||||

| Hesperidin | ORu | OH | OCH3 | |||||

| Hesperetin | OH | OH | H | |||||

| Liquiritigen | OH | H | OH | |||||

| Naringenin | OH | H | OH | |||||

| Anthocyanins | ||||||||

| Name | 7 | 3′ | 5′ | |||||

| Cyanidin | H | OH | H | |||||

| Delphidin | H | OH | OH | |||||

| Malvidin | OH | OCH3 | OCH3 | |||||

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Benzoic acid | |||

| Gallic acid | OH | OH | OH |

| Protocatechuic acid | OH | OH | H |

| Vanillic acid | OCH3 | OH | H |

| Cinnamic acid | |||

| Caffeic acid | OH | OH | H |

| Ferulic acid | OCH3 | OH | H |

| p-Coumaric acid | H | OH | H |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Naoi, M.; Wu, Y.; Shamoto-Nagai, M.; Maruyama, W. Mitochondria in Neuroprotection by Phytochemicals: Bioactive Polyphenols Modulate Mitochondrial Apoptosis System, Function and Structure. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2451. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20102451

Naoi M, Wu Y, Shamoto-Nagai M, Maruyama W. Mitochondria in Neuroprotection by Phytochemicals: Bioactive Polyphenols Modulate Mitochondrial Apoptosis System, Function and Structure. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019; 20(10):2451. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20102451

Chicago/Turabian StyleNaoi, Makoto, Yuqiu Wu, Masayo Shamoto-Nagai, and Wakako Maruyama. 2019. "Mitochondria in Neuroprotection by Phytochemicals: Bioactive Polyphenols Modulate Mitochondrial Apoptosis System, Function and Structure" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 20, no. 10: 2451. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20102451