l-Acetylcarnitine: A Mechanistically Distinctive and Potentially Rapid-Acting Antidepressant Drug

Abstract

:1. Introduction

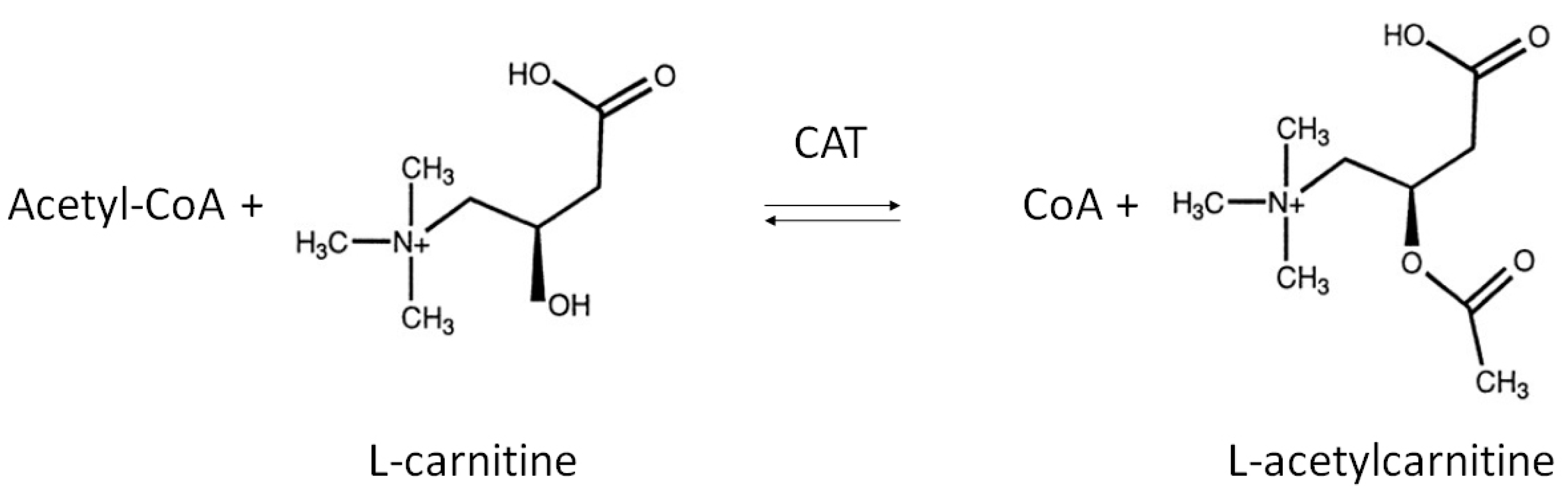

2. Role of Endogenous LAC in Energy Metabolism

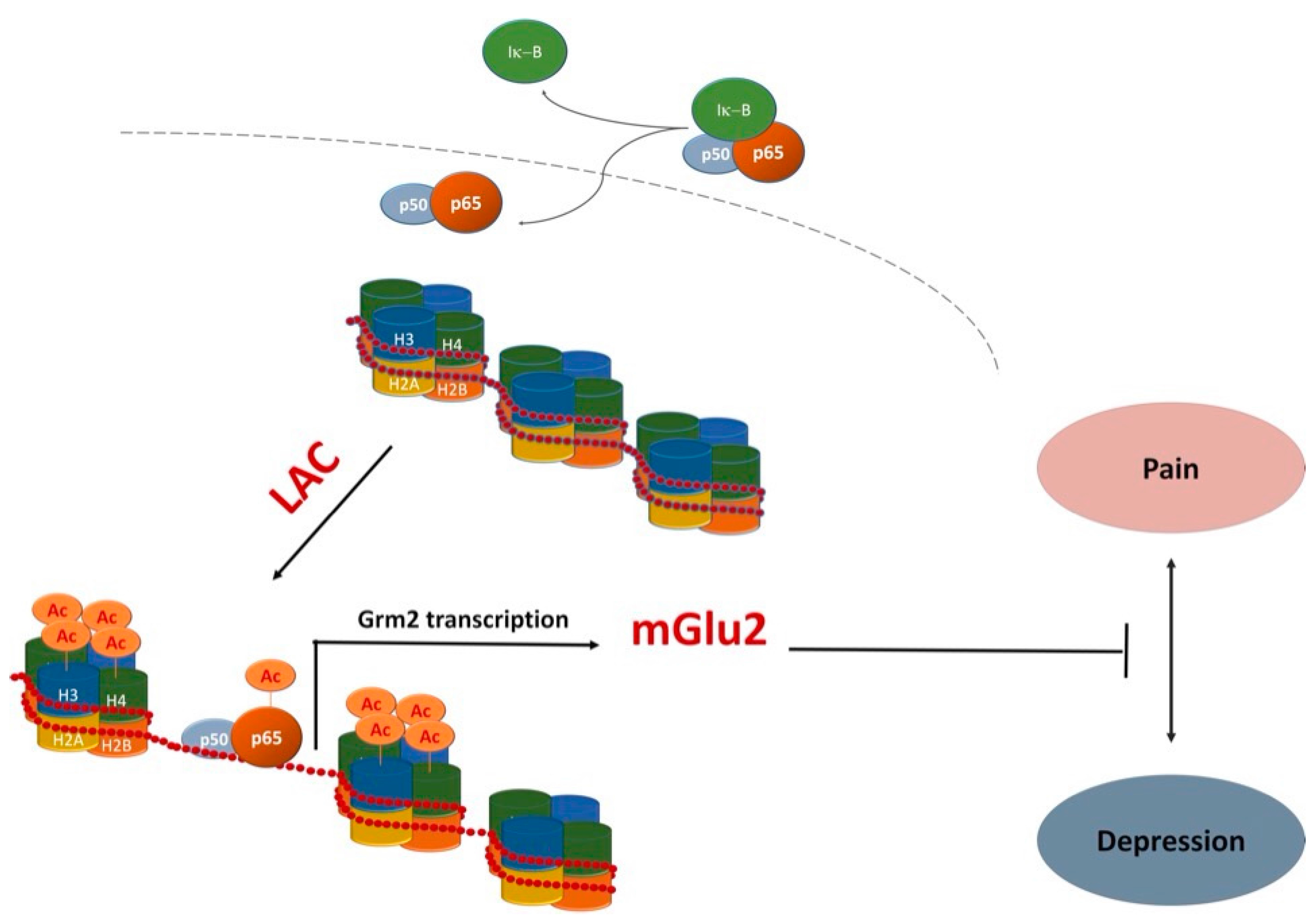

3. Pleiotropic Effects and Mechanisms for Exogenously Administered LAC

4. LAC as a Novel Antidepressant Drug with Unique Properties

5. Therapeutic Implications of LAC Unique Pharmacological Profile

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ahNG | Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis |

| AcetylCoA | Acetyl-Coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) |

| ahNPC | Adult Hippocampal Neural Progenitor Cell |

| BDNF | Brain Derived Growth Factor |

| CACT | Carnitine/Acetylcarnitine Translocase |

| CAT | Carnitine Acetyltransferase |

| ChAT | Choline Acetyltransferase |

| FSL | Flinders Sensitive Line |

| FRL | Flinders Resistant Line |

| GABA | Gamma-aminobutyric Acid |

| HAT | Histone Acetyltransferase |

| HDAC | Histone Deacetylase |

| Lys | Lysine |

| i.c.v. | Intracerebroventricular |

| LAC | l-AcetylCarnitine |

| Lepr | Leptin receptor |

| MDD | Major Depressive Disorder |

| mGlu2 | Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor type-2 |

| NAc | Nucleus Accumbens |

| MR | Mineralcorticoid Receptor |

| NPC | Neural Progenitor Cell |

| NF-κB | Nuclear Factor in the Kappa Light Chain Enhancer of B cells |

| OCTN2 | Organic Cation/Carnitine Transporter |

| RCT | Randomized Clinical Trials |

| UCMS | Unpredictable Chronic Mild Stress |

References

- Farrell, S.; Vogel, J.; Bieber, L.L. Entry of acetyl-l-carnitine into biosynthetic pathways. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1986, 876, 175–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettegrew, J.W.; Levine, J.; McClure, R.J. Acetyl-l-carnitine physical-chemical, metabolic, and therapeutic properties: Relevance for its mode of action in Alzheimer’s disease and geriatric depression. Mol. Psychiatry 2000, 5, 616–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nałecz, K.A.; Miecz, D.; Berezowski, V.; Cecchelli, R. Carnitine: Transport and physiological functions in the brain. Mol. Asp. Med. 2004, 25, 551–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Virmani, A.; Binienda, Z. Role of carnitine esters in brain neuropathology. Mol. Asp. Med. 2004, 25, 533–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabrese, V.; Giuffrida Stella, A.M.; Calvani, M.; Butterfield, D.A. Acetylcarnitine and cellular stress response: Roles in nutritional redox homeostasis and regulation of longevity genes. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2006, 17, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanelli, S.A.; Solenski, N.J.; Rosenthal, R.E.; Fiskum, G. Mechanisms of ischemic neuroprotection by acetyl-l-carnitine. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005, 1053, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiechio, S.; Copani, A.; de Petris, L.; Morales, M.E.; Nicoletti, F.; Gereau, R.W., IV. Transcriptional regulation of metabotropic glutamate receptor 2/3 expression by the NF-kappaB pathway in primary dorsal root ganglia neurons: A possible mechanism for the analgesic effect of l-acetylcarnitine. Mol. Pain 2006, 2, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuccurazzu, B.; Bortolotto, V.; Valente, M.M.; Ubezio, F.; Koverech, A.; Canonico, P.L.; Grilli, M. Upregulation of mGlu2 receptors via NF-κB p65 acetylation is involved in the proneurogenic and antidepressant effects of acetyl-l-carnitine. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 38, 2220–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pettegrew, J.W.; Klunk, W.E.; Panchalingam, K.; Kanfer, J.N.; McClure, R.J. Clinical and neurochemical effects of acetyl-l-carnitine in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 1995, 16, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, A.M. A 1-year controlled trial of acetyl-l-carnitine in early-onset AD. Neurology 2001, 56, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thal, L.J.; Calvani, M.; Amato, A.; Carta, A. A 1-year controlled trial of acetyl-l-carnitine in early-onset AD. Neurology 2000, 55, 805–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montgomery, S.A.; Thal, L.J.; Amrein, R. Meta-analysis of double blind randomized controlled clinical trials of acetyl-l-carnitine versus placebo in the treatment of mild cognitive impairment and mild Alzheimer’s disease. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2003, 18, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puca, F.M.; Genco, S.; Specchio, L.M.; Brancasi, B.; D’Ursi, R.; Prudenzano, A.; Miccoli, A.; Scarcia, R.; Martino, R.; Savarese, M. Clinical pharmacodynamics of acetyl-l-carnitine in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Res. 1990, 10, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goety, C.G.; Tanner, C.M.; Cohen, J.A.; Thelen, J.A.; Carroll, V.S.; Klawans, H.L.; Fariello, R.G. l-acetyl-carnitine in Huntington’s disease: Double-blind placebo controlled crossover study of drug effects on movement disorder and dementia. Mov. Disord. 1990, 5, 263–265. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De Falco, F.A.; D’Angelo, E.; Grimaldi, G.; Scafuro, F.; Sachez, F.; Caruso, G. Effect of the chronic treatment with l-acetylcarnitine in Down’s syndrome. Clin. Ter. 1994, 144, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bersani, G.; Meco, G.; Denaro, A.; Liberati, D.; Colletti, C.; Nicolai, R.; Bersani, F.S.; Koverech, A. l-Acetylcarnitine in dysthymic disorder in elderly patients: A double-blind, multicenter, controlled randomized study vs. fluoxetine. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013, 23, 1219–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanardi, R.; Smeraldi, E. A double-blind, randomised, controlled clinical trial of acetyl-l-carnitine vs. amisulpride in the treatment of dysthymia. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2006, 16, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Grandis, D.; Minardi, C. Acetyl-l-carnitine (levacecarnine) in the treatment of diabetic neuropathy. A long-term, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Drugs R D 2002, 3, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sima, A.A.; Calvani, M.; Mehra, M.; Amato, A. Acetyl-l-Carnitine Study Group. Acetyl-l-carnitine improves pain, nerve regeneration, and vibratory perception in patients with chronic diabetic neuropathy: An analysis of two randomized placebo-controlled trials. Diabetes Care 2005, 28, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Li, Q.; Li, Y.; Li, L.; Tian, H.; Sun, X. Acetyl-l-carnitine in the treatment of peripheral neuropathic pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0119479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Chen, X.; Li, Q.; Du, J.; Liu, Z.; Peng, Y.; Xu, M.; Li, Q.; Lei, M.; Wang, C.; et al. Effects of acetyl-l-carnitine and methylcobalamin for diabetic peripheral neuropathy: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. J. Diabetes Investig. 2016, 7, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osio, M.; Muscia, F.; Zampini, L.; Nascimbene, C.; Mailland, E.; Cargnel, A.; Mariani, C. Acetyl-l-carnitine in the treatment of painful antiretroviral toxic neuropathy in human immunodeficiency virus patients: An open label study. J. Peripher. Nerv. Syst. 2006, 11, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Curran, M.W.; Olson, J.; Morhart, M.; Sample, D.; Chan, K.M. Acetyl-l-carnitine (ALCAR) to enhance nerve regeneration in carpal tunnel syndrome: Study protocol for a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Trials 2016, 17, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leombruni, P.; Miniotti, M.; Colonna, F.; Sica, C.; Castelli, L.; Bruzzone, M.; Parisi, S.; Fusaro, E.; Sarzi-Puttini, P.; Atzeni, F.; et al. A randomised controlled trial comparing duloxetine and acetyl l-carnitine in fibromyalgic patients: Preliminary data. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2015, 33, S82–S85. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rossini, M.; di Munno, O.; Valentini, G.; Bianchi, G.; Biasi, G.; Cacace, E.; Malesci, D.; La Montagna, G.; Viapiana, O.; Adami, S. Double-blind, multicenter trial comparing acetyl l-carnitine with placebo in the treatment of fibromyalgia patients. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2007, 25, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brunner, S.; Kramar, K.; Denhardt, D.T.; Hofbauer, R. Cloning and characterization of murine carnitine acetyltransferase: Evidence for a requirement during cell cycle progression. Biochem. J. 1997, 322, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, D.; Govindasamy, L.; Lian, W.; Gu, Y.; Kukar, T.; Agbandje-McKenna, M.; McKenna, R. Structure of human carnitine acetyltransferase. Molecular basis for fatty acyl transfer. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 13159–13165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsay, R.R.; Arduini, A. The carnitine acyltransferases and their role in modulating acyl-CoA pools. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1993, 302, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsay, R.R.; Gandour, R.D.; van der Leij, F.R. Molecular enzymology of carnitine transfer and transport. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2001, 1546, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pande, S.V. A mitochondrial carnitine acylcarnitine translocase system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1975, 72, 883–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Indiveri, C.; Iacobazzi, V.; Tonazzi, A.; Giangregorio, N.; Infantino, V.; Convertini, P.; Console, L.; Palmieri, F. The mitochondrial carnitine/acylcarnitine carrier: Function, structure and physiopathology. Mol. Asp. Med. 2011, 32, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonazzi, A.; Giangregorio, N.; Console, L.; Indiveri, C. Mitochondrial carnitine/acylcarnitine translocase: Insights in structure/function relationships. Basis for drug therapy and side effects prediction. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2015, 15, 396–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madiraju, P.; Pande, S.V.; Prentki, M.; Madiraju, S.R. Mitochondrial acetylcarnitine provides acetyl groups for nuclear histone acetylation. Epigenetics 2009, 4, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bresolin, N.; Freddo, L.; Vergani, L.; Angelini, C. Carnitine, carnitine acyltransferases, and rat brain function. Exp. Neurol. 1982, 78, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shug, A.L.; Schmidt, M.J.; Golden, G.T.; Fariello, R.G. The distribution and role of carnitine in the mammalian brain. Life Sci. 1982, 31, 2869–2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnetti, L.; Gaiti, A.; Mecocci, P.; Cadini, D.; Senin, U. Pharmacokinetics of IV and oral acetyl-l-carnitine in a multiple dose regimen in patients with senile dementia of Alzheimer type. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 1992, 42, 89–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, O.S.; Chung, Y.B. HPLC determination and pharmacokinetics of endogenous acetyl-l-carnitine (ALC) in human volunteers orally administered a single dose of ALC. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2004, 27, 676–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miecz, D.; Januszewicz, E.; Czeredys, M.; Hinton, B.T.; Berezowski, V.; Cecchelli, R.; Nałecz, K.A. Localization of organic cation/carnitine transporter (OCTN2) in cells forming the blood-brain barrier. J. Neurochem. 2008, 104, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piovesan, P.; Pacifici, L.; Taglialatela, G.; Ramacci, M.T.; Angelucci, L. Acetyl-l-carnitine treatment increases choline acetyltransferase activity and NGF levels in the CNS of adult rats following total fimbria-fornix transection. Brain Res. 1994, 633, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taglialatela, G.; Navarra, D.; Cruciani, R.; Ramacci, M.T.; Alemà, G.S.; Angelucci, L. Acetyl-l-carnitine treatment increases nerve growth factor levels and choline acetyltransferase activity in the central nervous system of aged rats. Exp. Gerontol. 1994, 29, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foreman, P.J.; Perez-Polo, J.R.; Angelucci, L.; Ramacci, M.T.; Taglialatela, G. Effects of acetyl-l-carnitine treatment and stress exposure on the nerve growth factor receptor (p75NGFR) mRNA level in the central nervous system of aged rats. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 1995, 19, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sershen, H.; Harsing, L.G., Jr.; Banay-Schwartz, M.; Hashim, A.; Ramacci, M.T.; Lajtha, A. Effect of acetyl-l-carnitine on the dopaminergic system in aging brain. J. Neurosci. Res. 1991, 30, 555–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ando, S.; Tadenuma, T.; Tanaka, Y.; Fukui, F.; Kobayashi, S.; Ohashi, Y.; Kawabata, T. Enhancement of learning capacity and cholinergic synaptic function by carnitine in aging rats. J. Neurosci. Res. 2001, 66, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imperato, A.; Ramacci, M.T.; Angelucci, L. Acetyl-l-carnitine enhances acetylcholine release in the striatum and hippocampus of awake freely moving rats. Neurosci. Lett. 1989, 107, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fariello, R.G.; Ferraro, T.N.; Golden, G.T.; DeMattei, M. Systemic acetyl-l-carnitine elevates nigral levels of glutathione and GABA. Life Sci. 1988, 43, 289–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bähring, R.; Standhardt, H.; Martelli, E.A.; Grantyn, R. GABA-activated chloride currents of postnatal mouse retinal ganglion cells are blocked by acetylcholine and acetylcarnitine: How specific are ion channels in immature neurons? Eur. J. Neurosci. 1994, 6, 1089–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolezal, V.; Tucek, S. Utilization of citrate, acetylcarnitine, acetate, pyruvate and glucose for the synthesis of acetylcholine in rat brain slices. J. Neurochem. 1981, 36, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvani, M.; Carta, A.; Caruso, G.; Benedetti, N.; Iannuccelli, M. Action of acetyl-l-carnitine in neurodegeneration and Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1992, 663, 483–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szutowicz, A.; Bielarczyk, H.; Gul, S.; Zieliński, P.; Pawełczyk, T.; Tomaszewicz, M. Nerve growth factor and acetyl-l-carnitine evoked shifts in acetyl-CoA and cholinergic SN56 cell vulnerability to neurotoxic inputs. J. Neurosci. Res. 2005, 79, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiechio, S.; Copani, A.; Zammataro, M.; Battaglia, G.; Gereau, R.W., IV; Nicoletti, F. Transcriptional regulation of type-2 metabotropic glutamate receptors: An epigenetic path to novel treatments for chronic pain. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2010, 31, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasca, C.; Xenos, D.; Barone, Y.; Caruso, A.; Scaccianoce, S.; Matrisciano, F.; Battaglia, G.; Mathé, A.A.; Pittaluga, A.; Lionetto, L.; et al. l-acetylcarnitine causes rapid antidepressant effects through the epigenetic induction of mGlu2 receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 4804–4809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onofrj, M.; Ciccocioppo, F.; Varanese, S.; di Muzio, A.; Calvani, M.; Chiechio, S.; Osio, M.; Thomas, A. Acetyl-l-carnitine: From a biological curiosity to a drug for the peripheral nervous system and beyond. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2013, 13, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notartomaso, S.; Mascio, G.; Bernabucci, M.; Zappulla, C.; Scarselli, P.; Cannella, M.; Imbriglio, T.; Gradini, R.; Battaglia, G.; Bruno, V.; et al. Analgesia induced by the epigenetic drug, l-acetylcarnitine, outlasts the end of treatment in mouse models of chronic inflammatory and neuropathic pain. Mol. Pain 2017, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mai, A.; Massa, S.; Rotili, D.; Cerbara, I.; Valente, S.; Pezzi, R.; Simeoni, S.; Ragno, R. Histone deacetylation in epigenetics: An attractive target for anticancer therapy. Med. Res. Rev. 2005, 25, 261–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borrelli, E.; Nestler, E.J.; Allis, C.D.; Sassone-Corsi, P. Decoding the epigenetic language of neuronal plasticity. Neuron 2008, 60, 961–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiechio, S.; Caricasole, A.; Barletta, E.; Storto, M.; Catania, M.V.; Copani, A.; Vertechy, M.; Nicolai, R.; Calvani, M.; Melchiorri, D.; et al. l-Acetylcarnitine induces analgesia by selectively up-regulating mGlu2 metabotropic glutamate receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 2002, 61, 989–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zammataro, M.; Sortino, M.A.; Parenti, C.; Gereau, R.W., IV; Chiechio, S. HDAC and HAT inhibitors differently affect analgesia mediated by group II metabotropic glutamate receptors. Mol. Pain 2014, 10, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tempesta, E.; Casella, L.; Pirrongelli, C.; Janiri, L.; Calvani, M.; Ancona, L. l-acetylcarnitine in depressed elderly subjects. A cross-over study vs. placebo. Drugs Exp. Clin. Res. 1987, 13, 417–423. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Garzya, G.; Corallo, D.; Fiore, A.; Lecciso, G.; Petrelli, G.; Zotti, C. Evaluation of the effects of l-acetylcarnitine on senile patients suffering from depression. Drugs Exp. Clin. Res. 1990, 16, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bella, R.; Biondi, R.; Raffaele, R.; Pennisi, G. Effect of acetyl-l-carnitine on geriatric patients suffering from dysthymic disorders. Int. J. Clin. Pharmacol. Res. 1990, 10, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Veronese, N.; Stubb, B.; Solmi, M.; Carvalho, A. Acetyl-l-Carnitine supplementation and the treatment of depressive symptoms: A systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Psychosom. Med. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meister, R.; von Wolff, A.; Mohr, H.; Härter, M.; Nestoriuc, Y.; Hölzel, L.; Kriston, L. Comparative safety of pharmacologic treatments for persistent depressive disorder: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0153380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spalding, K.L.; Bergmann, O.; Alkass, K.; Bernard, S.; Salehpour, M.; Huttner, H.B.; Boström, E.; Westerlund, I.; Vial, C.; Buchholz, B.A.; et al. Dynamics of hippocampal neurogenesis in adult humans. Cell 2013, 153, 1219–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santarelli, L.; Saxe, M.; Gross, C.; Surget, A.; Battaglia, F.; Dulawa, S.; Weisstaub, N.; Lee, J.; Duman, R.; Arancio, O.; et al. Requirement of hippocampal neurogenesis for the behavioral effects of antidepressants. Science 2003, 301, 805–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- David, D.J.; Samuels, B.A.; Rainer, Q.; Wang, J.W.; Marsteller, D.; Mendez, I.; Drew, M.; Craig, D.A.; Guiard, B.P.; Guilloux, J.P.; et al. Neurogenesis-dependent and -independent effects of fluoxetine in an animal model of anxiety/depression. Neuron 2009, 62, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duman, R.S.; Nakagawa, S.; Malberg, J. Regulation of adult neurogenesis by antidepressant treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology 2001, 25, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malberg, J.E. Implications of adult hippocampal neurogenesis in antidepressant action. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2004, 29, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Dranovsky, A.; Hen, R. Hippocampal neurogenesis: Regulation by stress and antidepressants. Biol. Psychiatry 2006, 59, 1136–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boldrini, M.; Santiago, A.N.; Hen, R.; Dwork, A.J.; Rosoklija, G.B.; Tamir, H.; Arango, V.; John Mann, J. Hippocampal granule neuron number and dentate gyrus volume in antidepressant-treated and untreated major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 2013, 38, 1068–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittenger, C.; Duman, R.S. Stress, depression, and neuroplasticity: A convergence of mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology 2008, 33, 88–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisch, A.J.; Petrik, D. Depression and hippocampal neurogenesis: A road to remission? Science 2012, 338, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denis-Donini, S.; Dellarole, A.; Crociara, P.; Francese, M.T.; Bortolotto, V.; Quadrato, G.; Canonico, P.L.; Orsetti, M.; Ghi, P.; Memo, M.; et al. Impaired adult neurogenesis associated with short-term memory defects in NF-kappaB p50-deficient mice. J. Neurosci. 2008, 28, 3911–3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koo, J.W.; Russo, S.J.; Ferguson, D.; Nestler, E.J.; Duman, R.S. Nuclear factor-kappaB is a critical mediator of stress-impaired neurogenesis and depressive behavior. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 2669–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valente, M.M.; Allen, M.; Bortolotto, V.; Lim, S.T.; Conant, K.; Grilli, M. The MMP-1/PAR-1 axis enhances proliferation and neuronal differentiation of adult hippocampal neural progenitor cells. Neural Plast. 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nafez, S.; Oikawa, K.; Odero, G.L.; Sproule, M.; Ge, N.; Schapansky, J.; Abrenica, B.; Hatherell, A.; Cadonic, C.; Zhang, S.; et al. Early growth response 2 (Egr-2) expression is triggered by NF-κB activation. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 2015, 64, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaltschmidt, B.; Kaltschmidt, C. NF-KappaB in long-term memory and structural plasticity in the adult mammalian brain. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2015, 8, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cvijetic, S.; Bortolotto, V.; Manfredi, M.; Ranzato, E.; Marengo, E.; Salem, R.; Canonico, P.L.; Grilli, M. Cell autonomous and noncell-autonomous role of NF-κB p50 in astrocyte-mediated fate specification of adult neural progenitor cells. Glia 2017, 65, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bortolotto, V.; Cuccurazzu, B.; Canonico, P.L.; Grilli, M. NF-κB mediated regulation of adult hippocampal neurogenesis: Relevance to mood disorders and antidepressant activity. Biomed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valente, M.M.; Bortolotto, V.; Cuccurazzu, B.; Ubezio, F.; Meneghini, V.; Francese, M.T.; Canonico, P.L.; Grilli, M. α2δ ligands act as positive modulators of adult hippocampal neurogenesis and prevent depression-like behavior induced by chronic restraint stress. Mol. Pharmacol. 2012, 82, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meneghini, V.; Cuccurazzu, B.; Bortolotto, V.; Ramazzotti, V.; Ubezio, F.; Tzschentke, T.M.; Canonico, P.L.; Grilli, M. The noradrenergic component in tapentadol action counteracts μ-opioid receptor-mediated adverse effects on adult neurogenesis. Mol. Pharmacol. 2014, 85, 658–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bortolotto, V.; Grilli, M. Every cloud has a silver lining: Proneurogenic effects of Aβ oligomers and HMGB-1 via activation of the RAGE-NF-κB axis. CNS Neurol. Disord. Drug Targets 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolotto, V.; Mancini, F.; Mangano, G.; Salem, R.; Xia, E.; del Grosso, E.; Bianchi, M.; Canonico, P.L.; Polenzani, L.; Grilli, M. Proneurogenic effects of trazodone in murine and human neural progenitor cells. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2017, 8, 2027–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reagan-Shaw, S.; Nihal, M.; Ahmad, N. Dose translation from animal to human studies revisited. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 659–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaevitz, L.R.; Nicolai, R.; Lopez, C.M.; D’Iddio, S.; Iannoni, E.; Berger-Sweeney, J.E. Acetyl-l-carnitine improves behavior and dendritic morphology in a mouse model of Rett syndrome. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigio, B.; Mathe, A.A.; Sousa, V.C.; Zelli, D.; Svenningsson, P.; McEwen, B.; Nasca, C. Epigenetics and energetics in ventral hippocampus mediate rapid antidepressant action: Implications for treatment resistance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 7906–7911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christoffel, D.J.; Golden, S.A.; Dumitriu, D.; Robison, A.J.; Janssen, W.G.; Ahn, H.F.; Krishnan, V.; Reyes, C.M.; Han, M.H.; Ables, J.L.; et al. IκB kinase regulates social defeat stress-induced synaptic and behavioral plasticity. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bortolotto, V.; Grilli, M. Opiate analgesics as negative modulators of adult hippocampal neurogenesis: Potential implications in clinical practice. Front. Pharmacol. 2017, 8, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grilli, M. Chronic pain and adult hippocampal neurogenesis: Translational implications from preclinical studies. J. Pain Res. 2017, 10, 2281–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grilli, M.; Chiu, J.J.; Lenardo, M.J. NF-kappaB and Rel: Participants in a multiform transcriptional regulatory system. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1993, 143, 1–62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grilli, M.; Pizzi, M.; Memo, M.; Spano, P.F. Neuroprotection by aspirin and sodium salicylate through blockade of NF-kappaB activation. Science 1996, 274, 1383–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grilli, M.; Memo, M. Transcriptional pharmacology of neurodegenerative disorders: Novel venue towards neuroprotection against excitotoxicity? Mol. Psychiatry 1997, 2, 192–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perkins, N.D. Post-translational modifications regulating the activity and function of the nuclear factor kappa B pathway. Oncogene 2006, 25, 6717–6730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Lu, Y.; Xue, Z.; Li, C.; Wang, C.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, J.; Wei, X.; Chen, X.; Cui, W.; et al. Rapid-acting antidepressant-like effects of acetyl-l-carnitine mediated by PI3K/AKT/BDNF/VGF signaling pathway in mice. Neuroscience 2015, 285, 281–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Cesare Mannelli, L.; Vivoli, E.; Salvicchi, A.; Schiavone, N.; Koverech, A.; Messano, M.; Nicolai, R.; Benatti, P.; Bartolini, A.; Ghelardini, C. Antidepressant-like effect of artemin in mice: A mechanism for acetyl-l-carnitine activity on depression. Psychopharmacology 2011, 218, 347–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeland, O.B.; Meisingset, T.W.; Borges, K.; Sonnewald, U. Chronic acetyl-l-carnitine alters brain energy metabolism and increases noradrenaline and serotonin content in healthy mice. Neurochem. Int. 2012, 61, 100–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrari, F.; Gorini, A.; Villa, R.F. Functional proteomics of synaptic plasma membrane ATP-ases of rat hippocampus: Effect of l-acetylcarnitine and relationships with Dementia and Depression pathophysiology. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2015, 756, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lau, T.; Bigio, B.; Zelli, D.; McEwen, B.S.; Nasca, C. Stress-induced structural plasticity of medial amygdala stellate neurons and rapid prevention by a candidate antidepressant. Mol. Psychiatry 2017, 22, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rush, A.J.; Warden, D.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Fava, M.; Trivedi, M.H.; Gaynes, B.N.; Nierenberg, A.A. STAR*D: Revising conventional wisdom. CNS Drugs 2009, 23, 627–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berman, R.M.; Cappiello, A.; Anand, A.; Oren, D.A.; Heninger, G.R.; Charney, D.S.; Krystal, J.H. Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biol. Psychiatry 2000, 47, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preskorn, S.H. Ketamine: The hopes and the hurdles. Biol. Psychiatry 2012, 72, 522–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, I.; Morgan, C.; Curran, V.; Nutt, D.; Schlag, A.; McShane, R. Ketamine treatment for depression: Opportunities for clinical innovation and ethical foresight. Lancet Psychiatry 2017, 4, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, B.; Fong, J.; Galvez, V.; Shelker, W.; Loo, C.K. Side-effects associated with ketamine use in depression: A systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiechio, S. Modulation of chronic pain by metabotropic glutamate receptors. Adv. Pharmacol. 2016, 75, 63–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doan, L.; Manders, T.; Wang, J. Neuroplasticity underlying the comorbidity of pain and depression. Neural Plast. 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Clinical Condition | References |

|---|---|

| Alzheimer’s disease | [9,10,11,12] |

| Parkinson’s disease | [13] |

| Huntington’s disease | [14] |

| Down’s syndrome | [15] |

| Dysthymic/Depressive disorder | [16,17] |

| Diabetic neuropathy | [18,19,20,21] |

| HIV Neuropathy | [22] |

| Carpal tunnel syndrome | [23] |

| Fibromyalgia | [24,25] |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chiechio, S.; Canonico, P.L.; Grilli, M. l-Acetylcarnitine: A Mechanistically Distinctive and Potentially Rapid-Acting Antidepressant Drug. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19010011

Chiechio S, Canonico PL, Grilli M. l-Acetylcarnitine: A Mechanistically Distinctive and Potentially Rapid-Acting Antidepressant Drug. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018; 19(1):11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19010011

Chicago/Turabian StyleChiechio, Santina, Pier Luigi Canonico, and Mariagrazia Grilli. 2018. "l-Acetylcarnitine: A Mechanistically Distinctive and Potentially Rapid-Acting Antidepressant Drug" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 19, no. 1: 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19010011