Cesium Inhibits Plant Growth through Jasmonate Signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

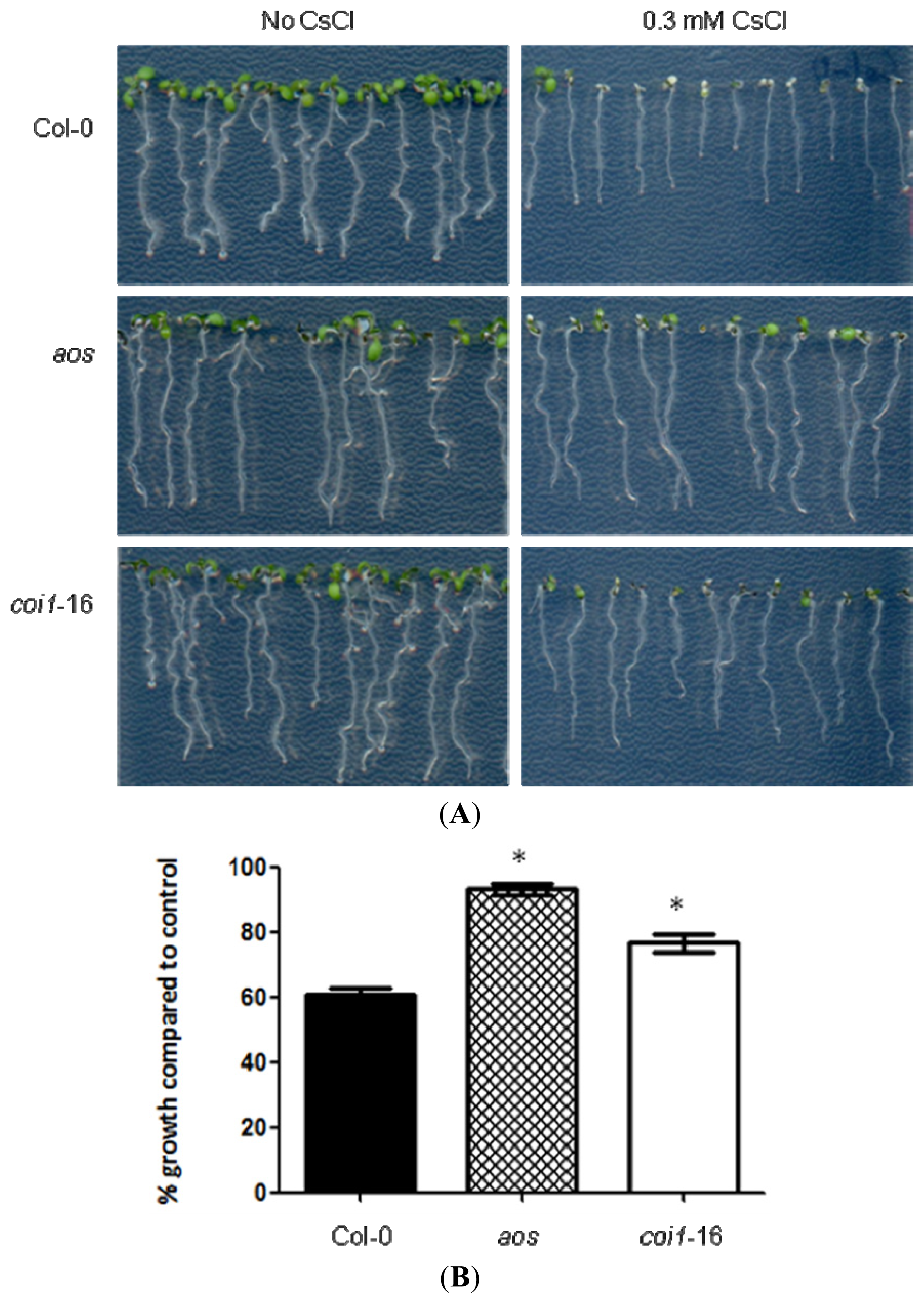

2.1. JA-Related Mutants Are Less Responsive to Cs+-Induced Growth Inhibition

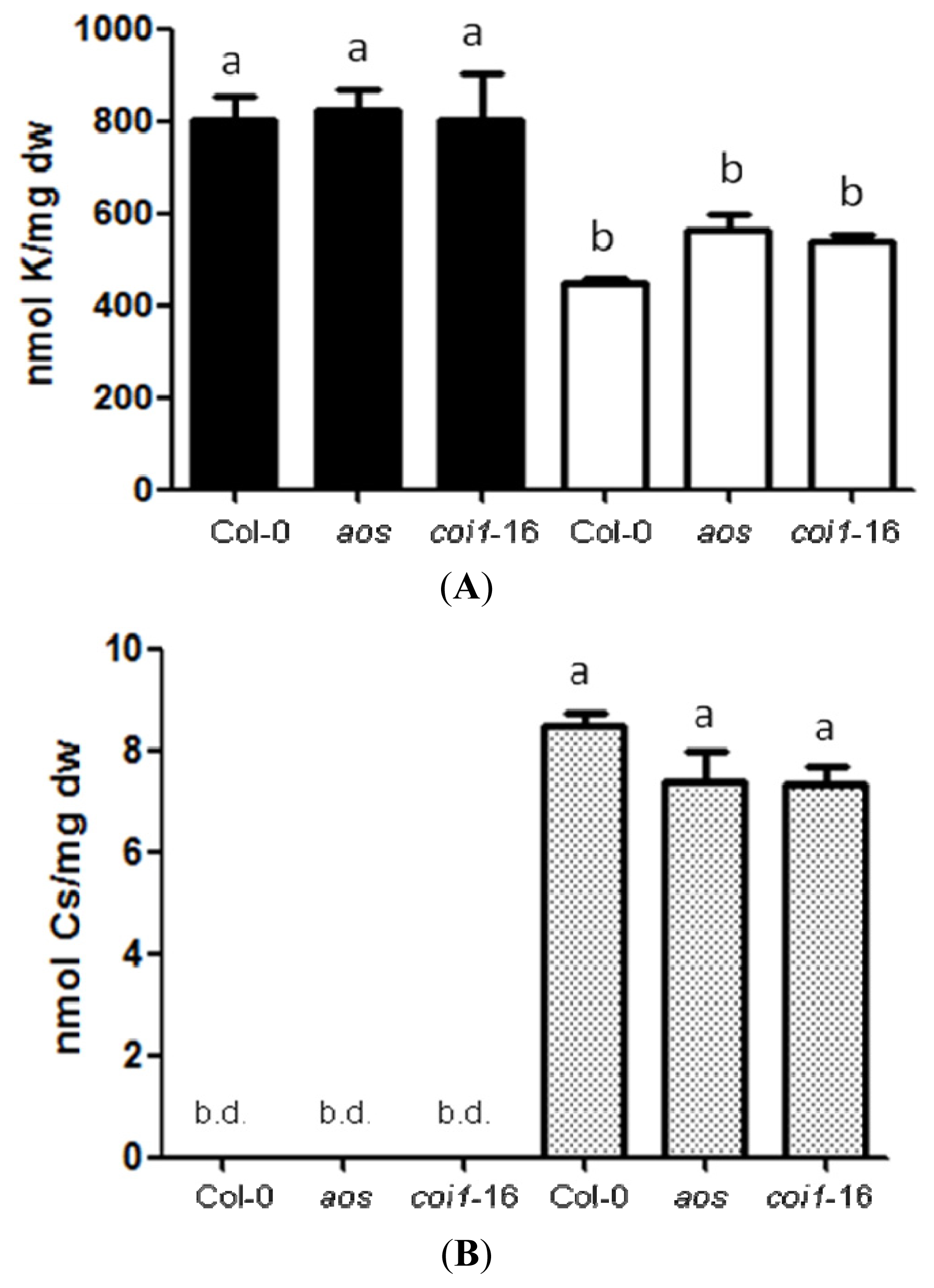

2.2. Resistance of JA-Related Mutants to Cs+ Was Not Due to Less Uptake of Cs+

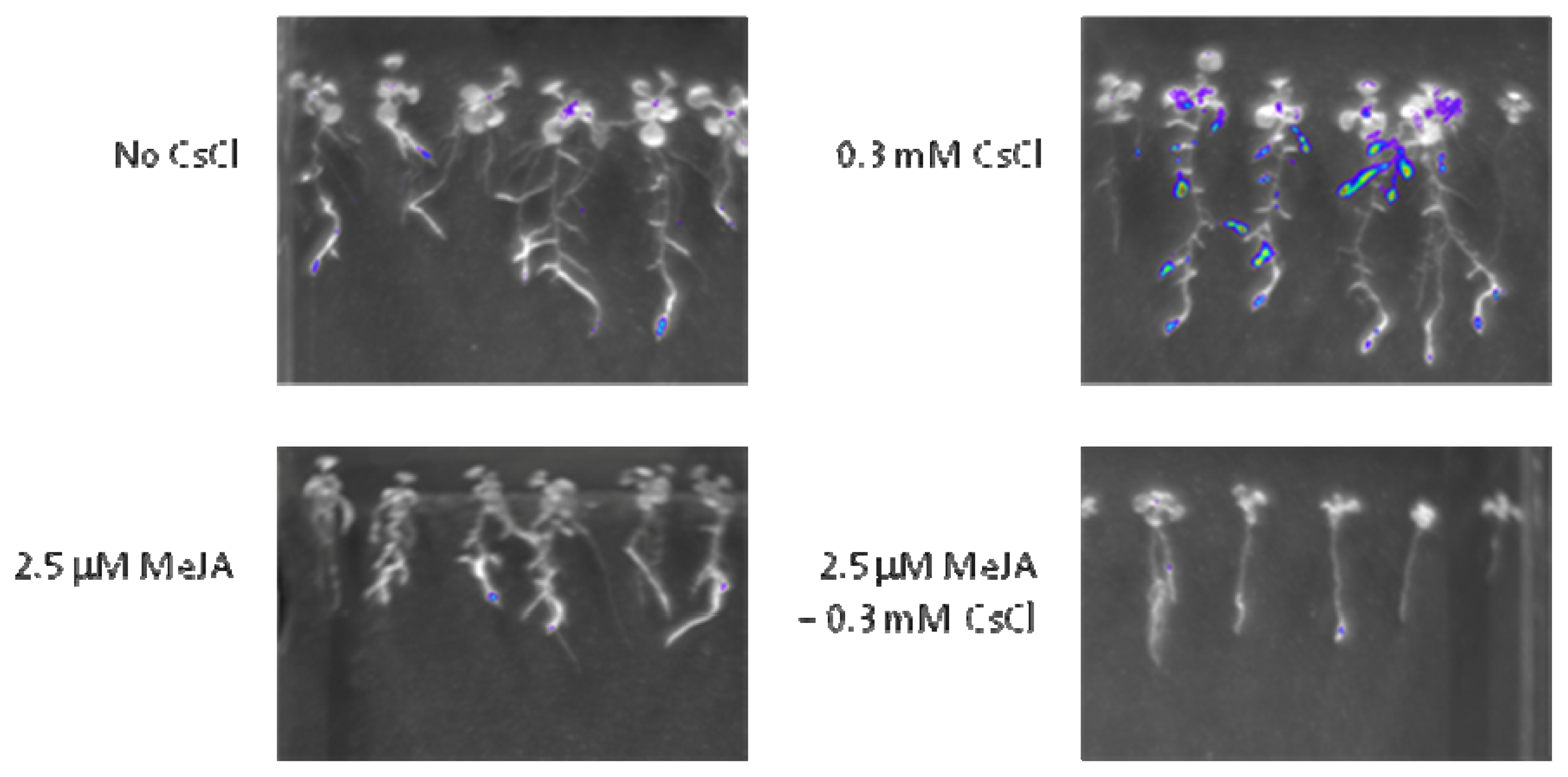

2.3. Cs+ Induces JA Signaling as well as HAK5 Expression

2.4. JA Antagonizes Cs+-Induced HAK5 Expression

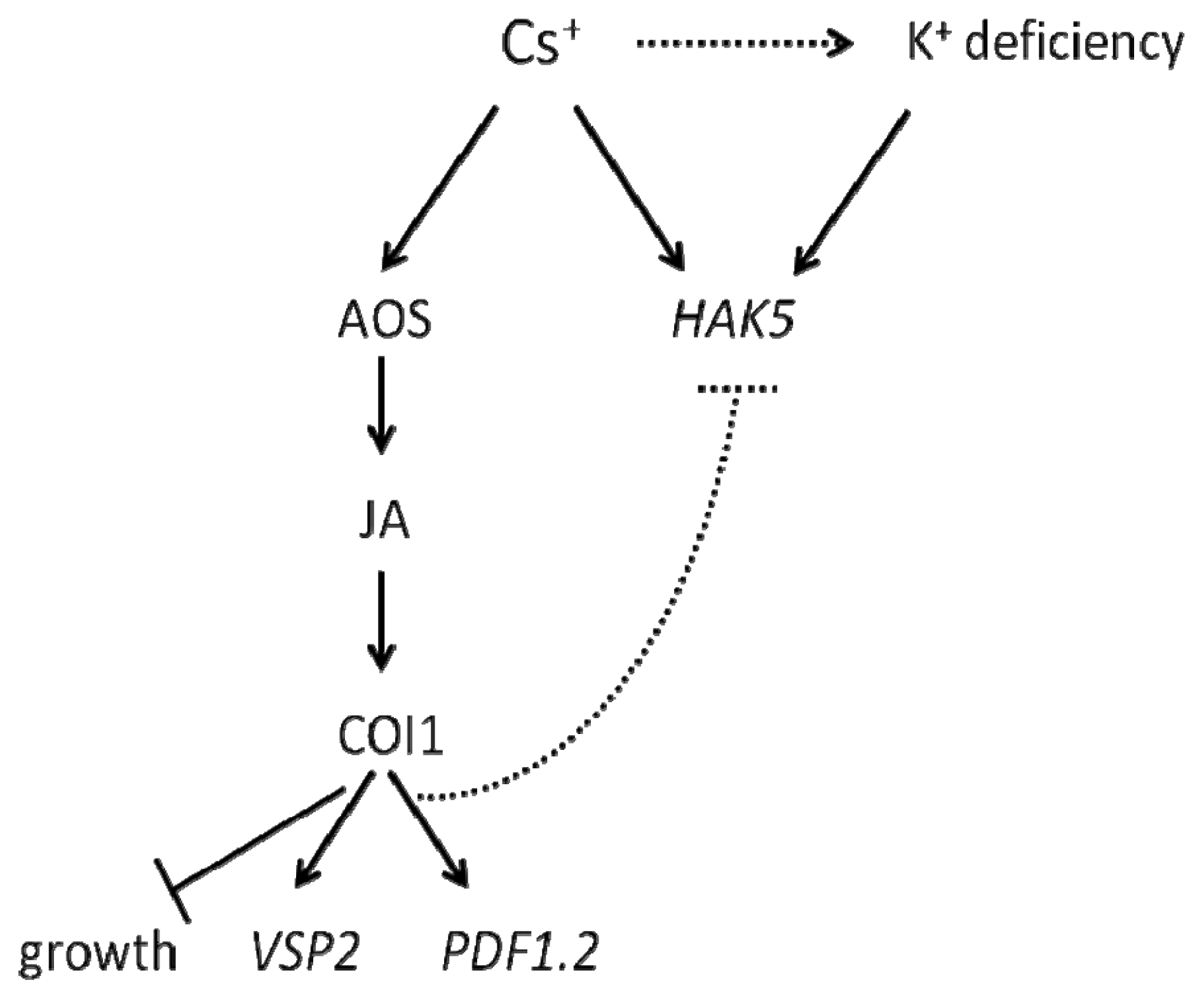

3. Discussion

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Plant Material and Growth Conditions

4.2. Root Growth Assay

4.3. Element Analysis

4.4. qRT-PCR Analysis

4.5. Luciferase Imaging

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Information

ijms-14-04545-s001.docxAcknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- White, P.J.; Broadley, M.R. Mechanisms of caesium uptake by plants. New Phytol 2000, 147, 241–256. [Google Scholar]

- Lasat, M.M.; Norvell, W.A.; Kochian, L.V. Potential for phytoextraction of 137Cs from a contaminated soil. Plant Soil 1997, 195, 99–106. [Google Scholar]

- Entry, J.A.; Vance, N.C.; Hamilton, M.A.; Zabowski, D.; Watrud, L.S.; Adriano, D.C. Phytoremediation of soil contaminated with low concentrations of radionuclides. Water Air Soil Poll 1996, 88, 167–176. [Google Scholar]

- Collander, R. Selective absorption of cations by higher plants. Plant Physiol 1941, 16, 691–720. [Google Scholar]

- Kanter, U.; Hauser, A.; Michalke, B.; Draxl, S.; Schaffner, A.R. Caesium and strontium accumulation in shoots of Arabidopsis thaliana: Genetic and physiological aspects. J. Exp. Bot 2010, 61, 3995–4009. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, Q.; Mercier, R.W.; Hua, B.G.; Fromm, H.; Berkowitz, G.A. Electrophysiological analysis of cloned cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels. Plant Physiol 2002, 128, 400–410. [Google Scholar]

- Balague, C.; Lin, B.Q.; Alcon, C.; Flottes, G.; Malmstrom, S.; Kohler, C.; Neuhaus, G.; Pelletier, G.; Gaymard, F.; Roby, D. HLM1, an essential signaling component in the hypersensitive response, is a member of the cyclic nucleotide-gated channel ion channel family. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 365–379. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.L.; Borsics, T.; Harrington, H.M.; Christopher, D.A. Arabidopsis AtCNGC10 rescues potassium channel mutants of E. coli, yeast and Arabidopsis and is regulated by calcium/calmodulin and cyclic GMP in E. coli. Funct. Plant Biol 2005, 32, 643–653. [Google Scholar]

- Schachtman, D.P.; Schroeder, J.I.; Lucas, W.J.; Anderson, J.A.; Gaber, R.F. Expression of an inward-rectifying potassium channel by the Arabidopsis KAT1 cDNA. Science 1992, 258, 1654–1658. [Google Scholar]

- Basset, M.; Conejero, G.; Lepetit, M.; Fourcroy, P.; Sentenac, H. Organization and expression of the gene coding for the potassium transport system AKT1 of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol 1995, 29, 947–958. [Google Scholar]

- Broadley, M.R.; Escobar-Gutierrez, A.J.; Bowen, H.C.; Willey, N.J.; White, P.J. Influx and accumulation of Cs+ by the akt1 mutant of Arabidopsis thaliana (L.) Heynh. lacking a dominant K+ transport system. J. Exp. Bot 2001, 52, 839–844. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, Z.; Hampton, C.R.; Shin, R.; Barkla, B.J.; White, P.J.; Schachtman, D.P. The high affinity K+ transporter AtHAK5 plays a physiological role in planta at very low K+ concentrations and provides a caesium uptake pathway in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot 2008, 59, 595–607. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.J.; Kwak, J.M.; Uozumi, N.; Schroeder, J.I. AtKUP1: An Arabidopsis gene encoding high-affinity potassium transport activity. Plant Cell 1998, 10, 51–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kobayashi, D.; Uozumi, N.; Hisamatsu, S.; Yamagami, M. AtKUP/HAK/KT9, a K+ transporter from Arabidopsis thaliana, mediates Cs+ uptake in Escherichia coli. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem 2010, 74, 203–205. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, J.Y.; Shin, R.; Schachtman, D.P. Ethylene mediates response and tolerance to potassium deprivation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 607–621. [Google Scholar]

- Armengaud, P.; Breitling, R.; Amtmann, A. The potassium-dependent transcriptome of Arabidopsis reveals a prominent role of jasmonic acid in nutrient signaling. Plant Physiol 2004, 136, 2556–2576. [Google Scholar]

- Armengaud, P.; Breitling, R.; Amtmann, A. Coronatine-insensitive 1 (COI1) mediates transcriptional responses of Arabidopsis thaliana to external potassium supply. Mol. Plant 2010, 3, 390–405. [Google Scholar]

- Troufflard, S.; Mullen, W.; Larson, T.R.; Graham, I.A.; Crozier, A.; Amtmann, A.; Armengaud, P. Potassium deficiency induces the biosynthesis of oxylipins and glucosinolates in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2010, 10, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, Y.J.; Tran, L.S.P.; Kojima, M.; Sakakibara, H.; Nishiyama, R.; Shin, R. Regulatory roles of cytokinins and cytokinin signaling in response to potassium deficiency in Arabidopsis. PLoS One 2012, 7, e47797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, R.; Burch, A.Y.; Huppert, K.A.; Tiwari, S.B.; Murphy, A.S.; Guilfoyle, T.J.; Schachtman, D.P. The Arabidopsis transcription factor MYB77 modulates auxin signal transduction. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 2440–2453. [Google Scholar]

- Wasternack, C. Jasmonates: An update on biosynthesis, signal transduction and action in plant stress response, growth and development. Ann. Bot 2007, 100, 681–697. [Google Scholar]

- Laudert, D.; Pfannschmidt, U.; Lottspeich, F.; Hollander-Czytko, H.; Weiler, E.W. Cloning, molecular and functional characterization of Arabidopsis thaliana allene oxide synthase (CYP 74), the first enzyme of the octadecanoid pathway to jasmonates. Plant Mol. Biol 1996, 31, 323–335. [Google Scholar]

- Chini, A.; Fonseca, S.; Fernandez, G.; Adie, B.; Chico, J.M.; Lorenzo, O.; Garcia-Casado, G.; Lopez-Vidriero, I.; Lozano, F.M.; Ponce, M.R.; et al. The JAZ family of repressors is the missing link in jasmonate signaling. Nature 2007, 448, 666–671. [Google Scholar]

- Thines, B.; Katsir, L.; Melotto, M.; Niu, Y.; Mandaokar, A.; Liu, G.H.; Nomura, K.; He, S.Y.; Howe, G.A.; Browse, J. JAZ repressor proteins are targets of the SCFCOI1 complex during jasmonate signaling. Nature 2007, 448, 661–665. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J.B.; Zhang, C.; Gu, M.; Bai, Z.Y.; Zhang, W.G.; Qi, T.C.; Cheng, Z.W.; Peng, W.; Luo, H.B.; Nan, F.J.; et al. The Arabidopsis CORONATINE INSENSITIVE1 protein is a jasmonate receptor. Plant Cell 2009, 21, 2220–2236. [Google Scholar]

- Sheard, L.B.; Tan, X.; Mao, H.B.; Withers, J.; Ben-Nissan, G.; Hinds, T.R.; Kobayashi, Y.; Hsu, F.F.; Sharon, M.; Browse, J.; et al. Jasmonate perception by inositol-phosphate-potentiated COI1-JAZ co-receptor. Nature 2010, 468, 400–405. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, D.X.; Feys, B.F.; James, S.; Nieto-Rostro, M.; Turner, J.G. COI1: An Arabidopsis gene required for jasmonate-regulated defense and fertility. Science 1998, 280, 1091–1094. [Google Scholar]

- Feys, B.J.F.; Benedetti, C.E.; Penfold, C.N.; Turner, J.G. Arabidopsis mutants selected for resistance to the phytotoxin coronatine are male-sterile, insensitive to methyl jasmonate, and resistant to a bacterial pathogen. Plant Cell 1994, 6, 751–759. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, C.; Turner, J.G. A conditionally fertile coi1 allele indicates cross-talk between plant hormone signaling pathways in Arabidopsis thaliana seeds and young seedlings. Planta 2002, 215, 549–556. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.H.; Halitschke, R.; Kim, H.B.; Baldwin, I.T.; Feldmann, K.A.; Feyereisen, R. A knock-out mutation in allene oxide synthase results in male sterility and defective wound signal transduction in Arabidopsis due to a block in jasmonic acid biosynthesis. Plant J 2002, 31, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- von Malek, B.; van der Graaff, E.; Schneitz, K.; Keller, B. The Arabidopsis male-sterile mutant dde2–2 is defective in the ALLENE OXIDE SYNTHASE gene encoding one of the key enzymes of the jasmonic acid biosynthesis pathway. Planta 2002, 216, 187–192. [Google Scholar]

- Staswick, P.E.; Su, W.P.; Howell, S.H. Methyl jasmonate inhibition of root growth and induction of a leaf protein are decreased in an Arabidopsis thaliana mutant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1992, 89, 6837–6840. [Google Scholar]

- Staswick, P.E.; Tiryaki, I.; Rowe, M.L. Jasmonate response locus JAR1 and several related Arabidopsis genes encode enzymes of the firefly luciferase superfamily that show activity on jasmonic, salicylic, and indole-3-acetic acids in an assay for adenylation. Plant Cell 2002, 14, 1405–1415. [Google Scholar]

- Pickett, F.B.; Wilson, A.K.; Estelle, M. The aux1 mutation of Arabidopsis confers both auxin and ethylene resistance. Plant Physiol 1990, 94, 1462–1466. [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki, K.; Tarkowski, P.; Matsumoto-Kitano, M.; Kato, T.; Sato, S.; Tarkowska, D.; Tabata, S.; Sandberg, G.; Kakimoto, T. Roles of Arabidopsis ATP/ADP isopentenyltransferases and tRNA isopentenyltransferases in cytokinin biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 16598–16603. [Google Scholar]

- Higuchi, M.; Pischke, M.S.; Mahonen, A.P.; Miyawaki, K.; Hashimoto, Y.; Seki, M.; Kobayashi, M.; Shinozaki, K.; Kato, T.; Tabata, S.; et al. In planta functions of the Arabidopsis cytokinin receptor family. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004, 101, 8821–8826. [Google Scholar]

- Guzman, P.; Ecker, J.R. Exploiting the triple response of Arabidopsis to identify ethylene-related mutants. Plant Cell 1990, 2, 513–523. [Google Scholar]

- Hua, J.; Chang, C.; Sun, Q.; Meyerowitz, E.M. Ethylene insensitivity conferred by Arabidopsis ERS gene. Science 1995, 269, 1712–1714. [Google Scholar]

- Dill, A.; Sun, T.P. Synergistic derepression of gibberellin signaling by removing RGA and GAI function in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics 2001, 159, 777–785. [Google Scholar]

- Penninckx, I.A.M.A.; Thomma, B.P.H.J.; Buchala, A.; Metraux, J.P.; Broekaert, W.F. Concomitant activation of jasmonate and ethylene response pathways is required for induction of a plant defensin gene in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 1998, 10, 2103–2113. [Google Scholar]

- Benedetti, C.E.; Xie, D.X.; Turner, J.G. COI1-dependent expression of an Arabidopsis vegetative storage protein in flowers and siliques and in response to coronatine or methyl jasmonate. Plant Physiol 1995, 109, 567–572. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, S.; Bell, E.; Sadka, A.; Mullet, J.E. Arabidopsis thaliana Atvsp is homologous to soybean VspA and VspB, genes encoding vegetative storage protein acid phosphatases, and is regulated similarly by methyl jasmonate, wounding, sugars, light and phosphate. Plant Mol. Biol 1995, 27, 933–942. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.J.; Heaton, A.C.P.; Carreira, L.; Meagher, R.B. Enhanced tolerance to and accumulation of mercury, but not arsenic, in plants overexpressing two enzymes required for thiol peptide synthesis. Physiol. Plant 2006, 128, 48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.J.; Dankher, O.P.; Carreira, L.; Smith, A.P.; Meagher, R.B. The shoot-specific expression of g-glutamylcysteine synthetase directs the long-distance transport of thiol-peptides to roots conferring tolerance to mercury and arsenic. Plant Physiol 2006, 141, 288–298. [Google Scholar]

- Marmiroli, M.; Visioli, G.; Antonioli, G.; Maestri, E.; Marmiroli, N. Integration of XAS techniques and genetic methodologies to explore Cs-tolerance in Arabidopsis. Biochimie 2009, 91, 180–191. [Google Scholar]

- Hampton, C.R.; Bowen, H.C.; Broadley, M.R.; Hammond, J.P.; Mead, A.; Payne, K.A.; Pritchard, J.; White, P.J. Cesium toxicity in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 2004, 136, 3824–3837. [Google Scholar]

- Hagiwara, S.; Miyazaki, S.; Rosenthal, N.P. Potassium current and effect of cesium on this current during anomalous rectification of egg cell membrane of a starfish. J. Gen. Physiol 1976, 67, 621–638. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, F.; Santa-Maria, G.E.; Rodriguez-Navarro, A. Cloning of Arabidopsis and barley cDNAs encoding HAK potassium transporters in root and shoot cells. Physiol. Plant 2000, 109, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, S.J.; Shin, R.; Schachtman, D.P. Expression of KT/KUP genes in Arabidopsis and the role of root hairs in K+ uptake. Plant Physiol 2004, 134, 1135–1145. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.J.; Ruzicka, D.; Shin, R.; Schachtman, D.P. The Arabidopsis AP2/ERF transcription factor RAP2.11 modulates plant response to low-potassium conditions. Mol. Plant 2012, 5, 1042–1057. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.L.; Kazan, K.; McGrath, K.C.; Maclean, D.J.; Manners, J.M. A role for the GCC-box in jasmonate-mediated activation of the PDF1.2 gene of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol 2003, 132, 1020–1032. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenzo, O.; Piqueras, R.; Sanchez-Serrano, J.J.; Solano, R. ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR1 integrates signals from ethylene and jasmonate pathways in plant defense. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 165–178. [Google Scholar]

- Zarei, A.; Korbes, A.P.; Younessi, P.; Montiel, G.; Champion, A.; Memelink, J. Two GCC boxes and AP2/ERF-domain transcription factor ORA59 in jasmonate/ethylene-mediated activation of the PDF1.2 promoter in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol 2011, 75, 321–331. [Google Scholar]

- Dombrecht, B.; Xue, G.P.; Sprague, S.J.; Kirkegaard, J.A.; Ross, J.J.; Reid, J.B.; Fitt, G.P.; Sewelam, N.; Schenk, P.M.; Manners, J.M.; Kazan, K. MYC2 differentially modulates diverse jasmonate-dependent functions in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2007, 19, 2225–2245. [Google Scholar]

© 2013 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Adams, E.; Abdollahi, P.; Shin, R. Cesium Inhibits Plant Growth through Jasmonate Signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 4545-4559. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14034545

Adams E, Abdollahi P, Shin R. Cesium Inhibits Plant Growth through Jasmonate Signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2013; 14(3):4545-4559. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14034545

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdams, Eri, Parisa Abdollahi, and Ryoung Shin. 2013. "Cesium Inhibits Plant Growth through Jasmonate Signaling in Arabidopsis thaliana" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 14, no. 3: 4545-4559. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms14034545