Isolation and Characterization of Cross-Amplification Microsatellite Panels for Species of Procapra (Bovidae; Antilopinae)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Isolation and Characterization of Cross-Amplification Microsatellite Loci

2.2. General Discussion of Results

2.2.1. Isolation Strategies for Polymorphic Microsatellite

2.2.2. Genetic Diversity of the Three Procapra Species

3. Experimental Section

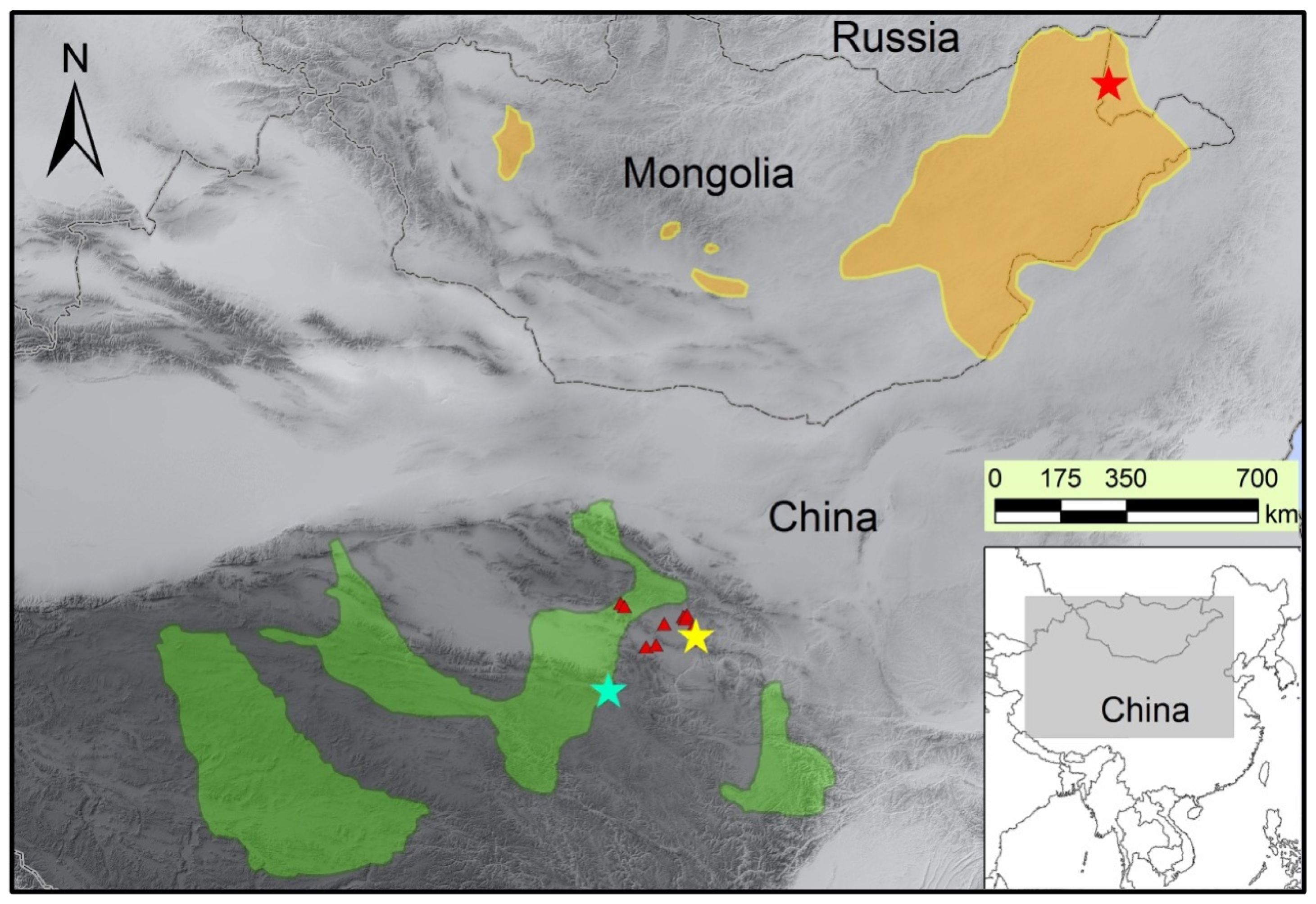

3.1. Sample Collection and Genomic DNA Extraction

3.2. Isolation of Microsatellite Markers

3.2.1. Cross-Amplification of Microsatellite Loci from Related Species

3.2.2. Construction of Enriched Genomic Library

3.3. Polymorphisms Assessment

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

- Conflict of InterestThe authors declare no conflict of interest in this study.

References

- Messier, W; Li, S.H; Stewart, C.B. The birth of microsatellites. Nature 1996, 381, 483. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, G.K; MacAvoy, E.S. Microsatellites: Consensus and controversy. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B 2000, 126, 455–476. [Google Scholar]

- Schlotterer, C. Evolutionary dynamics of microsatellite DNA. Chromosoma 2000, 109, 365–371. [Google Scholar]

- Buschiazzo, E; Gemmell, N.J. The rise, fall and renaissance of microsatellites in eukaryotic genomes. Bioessays 2006, 28, 1040–1050. [Google Scholar]

- Kruglyak, S; Durrett, R.T; Schug, M.D; Aquadro, C.F. Equilibrium distributions of microsatellite repeat length resulting from a balance between slippage events and point mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 10774. [Google Scholar]

- Ellegren, H. Microsatellites: Simple sequences with complex evolution. Nat. Rev. Genet 2004, 5, 435–445. [Google Scholar]

- Jarne, P; Lagoda, P.J.L. Microsatellites, from molecules to populations and back. Trends Ecol. Evol. (Amst.) 1996, 11, 424–429. [Google Scholar]

- Paetkau, D; Strobeck, C. Microsatellite analysis of genetic variation in black bear populations. Mol. Ecol 1994, 3, 489–495. [Google Scholar]

- Rannala, B; Mountain, J.L. Detecting immigration by using multilocus genotypes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1997, 94, 9197–9201. [Google Scholar]

- Balloux, F; Lugon-Moulin, N. The estimation of population differentiation with microsatellite markers. Mol. Ecol 2002, 11, 155–165. [Google Scholar]

- Paetkau, D; Calvert, W; Stirling, I; Strobeck, C. Microsatellite analysis of population structure in Canadian polar bears. Mol. Ecol 1995, 4, 347–354. [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, D.B; Linares, A.R; Cavallisforza, L.L; Feldman, M.W. Genetic absolute dating based on microsatellites and the origin of modern humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 6723–6727. [Google Scholar]

- Palsboll, P.J; Allen, J; Berube, M; Clapham, P.J; Feddersen, T.P; Hammond, P.S; Hudson, R.R; Jorgensen, H; Katona, S; Larsen, A.H; et al. Nature 1997, 388, 767–769.

- Woods, J.G; Paetkau, D; Lewis, D; McLellan, B.N; Proctor, M; Strobeck, C. Genetic tagging of free-ranging black and brown bears. Wildl. Soc. Bull 1999, 27, 616–627. [Google Scholar]

- Queller, D.C; Strassmann, J.E; Hughes, C.R. Microsatellites and kinship. Trends Ecol. Evol. (Amst.) 1993, 8, 285–288. [Google Scholar]

- Zane, L; Bargelloni, L; Patarnello, T. Strategies for microsatellite isolation: A review. Mol. Ecol 2002, 11, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hedgecock, D; Li, G; Hubert, S; Bucklin, K; Ribes, V. Widespread null alleles and poor cross-species amplification of microsatellite DNA loci cloned from the Pacific oyster, Crassostrea gigas. J. Shellfish Res 2004, 23, 379–386. [Google Scholar]

- Chapuis, M.P; Estoup, A. Microsatellite null alleles and estimation of population differentiation. Mol. Biol. Evol 2007, 24, 621–631. [Google Scholar]

- Hassanin, A; Delsuc, F; Ropiquet, A; Hammer, C; Jansen van Vuuren, B; Matthee, C; Ruiz-Garcia, M; Catzeflis, F; Areskoug, V; Nguyen, T.T; et al. Pattern and timing of diversification of Cetartiodactyla (Mammalia, Laurasiatheria), as revealed by a comprehensive analysis of mitochondrial genomes. C. R. Biol 2012, 335, 32–50. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.G; Gao, Z; Sun, Y. Current status of antelopes in China. J. For. Rev 1996, 7, 58–62. [Google Scholar]

- Mallon, D.P; Jiang, Z.G. Grazers on the plains: Challenges and prospects for large herbivores in Central Asia. J. Appl. Ecol. 2009, 46, 516–519. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.G; Wang, S. IUCN Antelope Survey and Action Plan Part 4: North America, the Middle East and Asia, Chapter 33 China. In Global Survey and Regional Action Plans on Antelope; Mallon, D.P., Kingswood, S.C., Eds.; IUCN: Gland, Switzerland, and Cambridge, UK, 2001; pp. 168–177. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar, Y.V; Wangchuk, R; Mishra, C. Decline of the Tibetan gazelle Procapra picticaudata in Ladakh, India. Oryx 2006, 40, 229–232. [Google Scholar]

- Namgail, T; Bagchi, S; Mishra, C; Bhatnagar, Y.V. Distributional correlates of the Tibetan gazelle Procapra picticaudata in Ladakh, northern India: Towards a recovery programme. Oryx 2008, 42, 107–112. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, K; Gao, Z. X; Guan, D.M; Bao, X.K; Bai, L.J; Wang, K.W. Variations of Distribution and Population Quantity of Mongolian Gazelle in the World. Chin. J. Ecol 1997, 38–42. [Google Scholar]

- Sokolov, V.E; Lushchekina, A.A. Procapra gutturosa. Mamm. Spec 1997, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.L; Jiang, Z.G; Ping, X.G; Cai, J; You, Z.Q; Li, C.W; Wu, Y.H. Current status and conservation of the Endangered Przewalski’s gazelle Procapra przewalskiiendemic to the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, China. Oryx 2012, 46, 145–153. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.G; Li, D.Q; Wang, Z.W. Population declines of Przewalski’s gazelle around Qinghai Lake, China. Oryx 2000, 34, 129–135. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.G. Przewalski’s Gazelle; China Forestry Publishing House: Beijing, China, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.Q; Jiang, Z.G; Beauchamp, G. Nonrandom mixing between groups of Przewalski’s gazelle and Tibetan gazelle. J. Mammal. 2010, 91, 674–680. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.H; Jiang, Z.G. Detecting the potential sympatric range and niche divergence between Asian endemic ungulates of Procapra. Naturwissenschaften 2012, 99, 553–565. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.G; Feng, Z.J; Wang, Z.W; Chen, L.W; Cai, P; Li, Y.B. Historical and current distributions of Przewalski’s gazelle. Acta Theriol. Sin 1995, 15, 241–245. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.Q; Jiang, Z.G; Li, C.W. Dietary overlap of Przewalski's gazelle, Tibetan gazelle, and Tibetan sheep on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Wildl. Manage 2008, 72, 944–948. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J; Jiang, Z.G; Zeng, Y; Turghan, M; Fang, H; Li, C.W. Effect of anthropogenic landscape features on population genetic differentiation of Przewalski’s gazelle: Main role of human settlement. PLoS One 2011, 6, e20144. [Google Scholar]

- Lhagvasuren, B; Milner-Gulland, E. The status and management of the Mongolian gazelle Procapra gutturosa population. Oryx 1997, 31, 127–134. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar, Y.V; Seth, C; Takpa, J; Ul-Haq, S; Namgail, T; Bagchi, S; Mishra, C. A strategy for conservation of the Tibetan gazelle Procapra picticaudata in Ladakh. Conserv. Soc 2007, 5, 262. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2011.2. Available online: http://www.iucnredlist.org accessed on 1 May 2012.

- Zhang, F.F; Jiang, Z.G. Mitochondrial phylogeography and genetic diversity of Tibetan gazelle (Procapra picticaudata): Implications for conservation. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol 2006, 41, 313–321. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J; Jiang, Z.G. Genetic diversity, population genetic structure and demographic history of Przewalski's gazelle (Procapra przewalskii): Implications for conservation. Conserv. Genet 2011, 12, 1457–1468. [Google Scholar]

- Sorokin, P; Kiriliuk, V; Lushchekina, A; Kholodova, M. Genetic diversity of the Mongolian gazelle Procapra guttorosa Pallas, 1777. Russ. J. Genet 2005, 41, 1101–1105. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, R.H; Jiang, Z.G; Hu, Z; Yang, W.L. Phylogenetic relationships of Chinese antelopes (subfamily Antilopinae) based on mitochondrial ribosomal RNA gene sequences. J. Zool 2003, 261, 227–237. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.F. Comparative study on phylogeography and demogaphy of Tibetan antelope (Patholops hodgsonii) and Tibetan gazelle (Procapra picticaudata). M.S. Thesis, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, July 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J. Phylogeography and Landscape Genetics of Przewalski’s Gazelle Procapra Przewalskii. M.S. Thesis, Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, S.J; Barnowe-Meyer, K.K; Gebhardt, K.J; Balkenhol, N; Waits, L.P; Byers, J.A. Ten polymorphic microsatellite markers for pronghorn (Antilocapra americana). Conserv. Genet. Resour 2010, 2, 81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Huebinger, R.M; de Maar, T.W.J; Woodruff, L.H; Pomp, D; Louis, E.E., Jr. Characterization of eight microsatellite loci in Grant’s gazelle (Gazella granti). Mol. Ecol. Notes 2006, 6, 1150–1151. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, A; Dodds, K; Ede, A; Pierson, C; Montgomery, G; Garmonsway, H; Beattie, A; Davies, K; Maddox, J; Kappes, S. An autosomal genetic linkage map of the sheep genome. Genetics 1995, 140, 703–724. [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, M.D; Kappes, S.M; Keele, J.W; Stone, R.T; Sunden, S.L.F; Hawkins, G.A; Toldo, S.S; Fries, R; Grosz, M.D; Yoo, J. A genetic linkage map for cattle. Genetics 1994, 136, 619–639. [Google Scholar]

- Rice, W.R. Analyzing tables of statistical tests. Evolution 1989, 43, 223–225. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, S.S; Sargeant, L.L; King, T.J; Mattick, J.S; Georges, M; Hetzel, D.J.S. The conservation of dinucleotide microsatellites among mammalian genomes allows the use of heterologous PCR primer pairs in closely related species. Genomics 1991, 10, 654–660. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix, R; Hauswaldt, J.S; Veith, M; Steinfartz, S. Strong correlation between cross-amplification success and genetic distance across all members of ‘True Salamanders’ (Amphibia: Salamandridae) revealed by Salamandra salamandra-specific microsatellite loci. Mol. Ecol. Resour 2010, 10, 1038–1047. [Google Scholar]

- Pepin, L; Amigues, Y; Lepingle, A; Berthier, J.L; Bensaid, A; Vaiman, D. Sequence conservation of microsatellites between Bos taurus (cattle), Capra hircus (goat) and related species. Heredity 1995, 74, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Pillay, K; Dawson, D.A; Horsburgh, G.J; Perrin, M.R; Burke, T; Taylor, T.D. Twenty-two polymorphic microsatellite loci aimed at detecting illegal trade in the Cape parrot, Poicephalus robustus (Psittacidae, AVES). Mol. Ecol. Resour 2010, 10, 142–149. [Google Scholar]

- Techen, N; Arias, R.S; Glynn, N.C; Pan, Z.Q; Khan, I.A; Scheffler, B.E. Optimized construction of microsatellite-enriched libraries. Mol. Ecol. Resour 2010, 10, 508–515. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.M; Sun, J.T; Xue, X.F; Zhu, W.C; Hong, X.Y. Development and Characterization of 18 Novel EST-SSRs from the Western Flower Thrips, Frankliniella occidentalis (Pergande). Int. J. Mol. Sci 2012, 13, 2863–2876. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, T.J; Sun, D.Q; Sun, Y.N; Wang, R.X. Development of 30 Novel Polymorphic Expressed Sequence Tags (EST)-Derived Microsatellite Markers for the Miiuy CroakerMiichthys miiuy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 4021–4026. [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, D.A; Horsburgh, G.J; Kupper, C; Stewart, I.R.K; Ball, A.D; Durrant, K.L; Hansson, B; Bacon, I; Bird, S; Klein, A; et al. New methods to identify conserved microsatellite loci and develop primer sets of high cross-species utility—As demonstrated for birds. Mol. Ecol. Resour 2010, 10, 475–494. [Google Scholar]

- Guichoux, E; Lagache, L; Wagner, S; Chaumeil, P; Leger, P; Lepais, O; Lepoittevin, C; Malausa, T; Revardel, E; Salin, F; et al. Current trends in microsatellite genotyping. Mol. Ecol. Resour 2011, 11, 591–611. [Google Scholar]

- Castoe, T.A; Poole, A.W; Gu, W.J; de Koning, A.P.J; Daza, J.M; Smith, E.N; Pollock, D.D. Rapid identification of thousands of copperhead snake (Agkistrodon contortrix) microsatellite loci from modest amounts of 454 shotgun genome sequence. Mol. Ecol. Resour 2010, 10, 341–347. [Google Scholar]

- Database for Molecular Ecology Resources. Available online: http://tomato.bio.trinity.edu accessed on 1 May 2004.

- Brotherton, P.N.M; Pemberton, J.M; Komers, P.E; Malarky, G. Genetic and behavioural evidence of monogamy in a mammal, Kirk’s dik–dik (Madoqua kirkii). Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci 1997, 264, 675–681. [Google Scholar]

- Beja-Pereira, A; Zeyl, E; Ouragh, L; Nagash, H; Ferrand, N; Taberlet, P; Luikart, G. Twenty polymorphic microsatellites in two of North Africa’s most threatened ungulates: Gazella dorcas and Ammotragus lervia (Bovidae; Artiodactyla). Mol. Ecol. Notes 2004, 4, 452–455. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.J; Zhang, B.W; Wei, F.W; Li, M. Isolation and characterization of microsatellite loci for the red panda, Ailurus fulgens. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2005, 5, 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, M.B; Pincus, E.L; di Fiore, A; Fleischer, R.C. Universal linker and ligation procedures for construction of genomic DNA libraries enriched for microsatellites. Biotechniques 1999, 27, 500–504. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, M; Rousset, F. Population genetics software for exact tests and ecumenicism. J. Hered 1995, 86, 248–249. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, T.C; Slate, J; Kruuk, L.E.B; Pemberton, J.M. Statistical confidence for likelihood-based paternity inference in natural populations. Mol. Ecol 1998, 7, 639–655. [Google Scholar]

| Locus | Repeat motif | Primer sequences (5′–3′) | Size range (bp) | Tm (°C) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC1 # | (AC)14 | F: TTGGCAGGTGGATTATTTAC R: TGGTTGTCAATGGAAGGAA | 171–199 | 50 | This study |

| AC29 # | (AC)14 | F: AGGACGGCACTTAAACTTATG R: TATCATTGTCAGGCTTCTCT | 169–198 | 50 | This study |

| AC35 # | (AC)12GAAGTATA T(AC)4 | F: TGGACAGAAGAGCGTAATG R: TCCTTGTGGCTGAGTAGTA | 210–222 | 50 | This study |

| AC77 # | (GT)13 | F: CACAGTCTCTTCTCATAATGC R: CGGATTCTTTACCTCATACAC | 147–161 | 50 | This study |

| AC91 # | (AC)14 | F: TTGGTCGTACTGACTGGTA R: GGAGTGACTGAGGACAGA | 176–200 | 50 | This study |

| AC170 # | (AC)19 | F: TCTCAAGAGGCAGGTCAG R: GATTCCTTTGGCTCCTAGAAG | 230–260 | 50 | This study |

| AC230 # | (AC)16ATATGC (AC)6 | F: TGGCTGAGCAACTAAGAG R: GGGAAATACTTGGGTAACAG | 152–168 | 50 | This study |

| AC244 # | (AC)6 (GT)14 (T)5G(T)9C(T)9 | F: GGGATAGCAGAGAGTCAGA R: GGAAGGAACAATTAGGAGTATG | 332–350 | 50 | This study |

| AC299 # | (AC)5T(AC)8 | F: CGGTGTTCATATAACAGATTCC R: GGTTGCTCAGTGGTCTCA | 159–189 | 50 | This study |

| Aam9 † | (GT)15 | F: ATGTGGGAGACTTGATGATG R: AAGACTGGAGACTGGGATTATC | 205–227 | 52 | [44] |

| HDZ8 † | (AC)14 | F: GACAAACACTCAGAAGGCAAAG R: GGTGGCAGGACTGAGCAAG | 132–166 | 50 | [45] |

| HDZ496 † | (AC)15 | F: GTTTTTCCAGATGGTATTTTCCTC R: GTATTCGGCTGAAGGGACC | 228–250 | 48 | [45] |

| MAF23 † | (GT)20 | F: GTGGAGGAATCTTGACTTGTGATAG R: GGCTATAGTCCATGGAGTCGCAG | 124–160 | 50 | [46] |

| VH34 † | (AC)17 | F: TCGTAAGAGTGGACACAACTGAGCG R: CGCAGTATTTAGTCCTTTTAATAATGGC | 81–101 | 50 | [46] |

| BM4505 † | (ACAT)4(AC)11 | F: TTATCTTGGCTTCTGGGTGC R: ATCTTCACTTGGGATGCAGG | 240–258 | 48 | [47] |

| AF5 ‡ | (CA)18 | F: GTGGGAAGAGATAGAGGAAGC R: GAGCCACAAGGCACAGCCAAC | 135–157 | 51 | [43] |

| BM1225 ‡ | (CT)13TA(CA)18 | F: TTTCTCAACAGAGGTGTCCAC R: ACCCCTATCACCATGCTCTG | 231–275 | 50 | [43] |

| CSSM43 ‡ | (CA)15AT(CT)5 | F: AAAACTCTGGGAACTTGAAAACTA R: GTTACAAATTTAAGAGACAGAGTT | 246–268 | 48 | [43] |

| RT1 ‡ | (GT)22 | F: TGCCTTCTTTCATCCAACAA R: CATCTTCCCATCCTCTTTAC | 195–233 | 50 | [43] |

| TEXAN-15 ‡ | (CT)9TT(CT)5GCAG ATA(CA)20 | F: TCGCAAACAGTCAGAGACCACTC R: TGGATGAGAAAGAAGAGCAGAGTTG | 203–227 | 50 | [43] |

| Locus | No. of samples | No. of alleles | HO | HE | PIC | PHW | Null allele frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC1 | 16 | 6 | 0.500 | 0.772 | 0.709 | 0.010 | 0.209 |

| AC29 | 16 | 6 | 0.375 | 0.667 | 0.695 | 0.004 | 0.276 |

| AC35 | 16 | 5 | 0.438 | 0.627 | 0.557 | 0.003 | 0.212 |

| AC77 | 16 | 6 | 0.000 | 0.807 | 0.748 | 0.000 * | 1.000 |

| AC91 | 16 | 8 | 0.625 | 0.851 | 0.801 | 0.004 | 0.145 |

| AC170 | 16 | 13 | 1.000 | 0.923 | 0.885 | 0.000 * | −0.057 |

| AC230 | 16 | 7 | 0.688 | 0.815 | 0.757 | 0.013 | 0.064 |

| AC244 | 16 | 6 | 0.625 | 0.593 | 0.546 | 0.836 | −0.091 |

| AC299 | 16 | 9 | 0.813 | 0.859 | 0.814 | 0.038 | 0.014 |

| Aam9 | 16 | 7 | 0.813 | 0.829 | 0.776 | 0.252 | −0.008 |

| HDZ8 | 16 | 13 | 0.938 | 0.925 | 0.888 | 0.003 | −0.026 |

| HDZ496 | 16 | 11 | 0.875 | 0.905 | 0.865 | 0.077 | 0.005 |

| MAF23 | 16 | 12 | 0.875 | 0.897 | 0.857 | 0.052 | −0.003 |

| VH34 | 16 | 8 | 0.625 | 0.857 | 0.810 | 0.002 | * 0.145 |

| BM4505 | 16 | 4 | 0.563 | 0.599 | 0.531 | 0.379 | 0.020 |

| AF5 | 16 | 8 | 0.750 | 0.869 | 0.823 | 0.096 | 0.064 |

| BM1225 | 16 | 11 | 0.688 | 0.919 | 0.881 | 0.000 * | 0.123 |

| CSSM43 | 16 | 3 | 0.938 | 0.643 | 0.552 | 0.029 | −0.223 |

| RT1 | 16 | 8 | 0.500 | 0.859 | 0.810 | 0.001 * | 0.242 |

| TEXAN-15 | 16 | 9 | 0.625 | 0.871 | 0.825 | 0.000 * | 0.157 |

| Locus | No. of samples | No. of alleles | HO | HE | PIC | PHW | Null allele frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC1 | 22 | 12 | 0.864 | 0.904 | 0.872 | 0.010 | 0.009 |

| AC29 | 22 | 14 | 0.909 | 0.927 | 0.898 | 0.573 | −0.003 |

| AC35 | 22 | 5 | 0.682 | 0.723 | 0.653 | 0.646 | 0.022 |

| AC77 | 22 | 5 | 0.500 | 0.661 | 0.610 | 0.150 | 0.133 |

| AC91 | 22 | 10 | 0.818 | 0.881 | 0.845 | 0.026 | 0.025 |

| AC170 | 22 | 12 | 0.864 | 0.921 | 0.891 | 0.001 * | 0.020 |

| AC230 | 22 | 10 | 0.773 | 0.870 | 0.833 | 0.201 | 0.052 |

| AC244 | 22 | 15 | 0.818 | 0.914 | 0.884 | 0.119 | 0.044 |

| AC299 | 22 | 11 | 0.818 | 0.825 | 0.791 | 0.273 | 0.001 |

| Aam9 | 22 | 12 | 0.682 | 0.883 | 0.850 | 0.037 | 0.120 |

| HDZ8 | 22 | 12 | 0.818 | 0.793 | 0.759 | 0.610 | −0.058 |

| HDZ496 | 22 | 9 | 0.636 | 0.819 | 0.775 | 0.057 | 0.112 |

| MAF23 | 22 | 14 | 0.955 | 0.928 | 0.900 | 0.018 | −0.028 |

| VH34 | 22 | 10 | 0.727 | 0.764 | 0.726 | 0.521 | 0.020 |

| BM4505 | 22 | 4 | 0.500 | 0.602 | 0.542 | 0.075 | 0.063 |

| AF5 | 22 | 14 | 0.955 | 0.886 | 0.856 | 0.814 | −0.053 |

| BM1225 | 22 | 20 | 0.818 | 0.935 | 0.907 | 0.008 | 0.056 |

| CSSM43 | 22 | 8 | 0.864 | 0.804 | 0.754 | 0.981 | −0.048 |

| RT1 | 22 | 13 | 0.909 | 0.892 | 0.860 | 0.465 | −0.024 |

| TEXAN-15 | 22 | 11 | 0.773 | 0.884 | 0.850 | 0.091 | 0.063 |

| Locus | No. of samples | No. of alleles | HO | HE | PIC | PHW | Null allele frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC1 | 15 | 5 | 0.600 | 0.543 | 0.496 | 0.895 | −0.079 |

| AC29 | 15 | 5 | 0.933 | 0.786 | 0.721 | 0.470 | −0.112 |

| AC35 | 15 | 3 | 0.800 | 0.570 | 0.456 | 0.093 | −0.200 |

| AC77 | 15 | 5 | 0.333 | 0.816 | 0.755 | 0.000 * | 0.400 |

| AC91 | 15 | 4 | 0.667 | 0.559 | 0.491 | 1.000 | −0.116 |

| AC170 | 15 | 5 | 0.733 | 0.793 | 0.728 | 0.101 | 0.025 |

| AC230 | 15 | 5 | 0.733 | 0.763 | 0.690 | 0.278 | −0.002 |

| AC244 | 15 | 4 | 0.333 | 0.715 | 0.635 | 0.000 * | 0.368 |

| AC299 | 15 | 5 | 0.467 | 0.749 | 0.686 | 0.005 | 0.231 |

| Aam9 | 15 | 5 | 0.333 | 0.578 | 0.545 | 0.009 | 0.282 |

| HDZ8 | 15 | 5 | 0.333 | 0.412 | 0.381 | 0.192 | 0.059 |

| HDZ496 | 15 | 4 | 0.600 | 0.524 | 0.432 | 0.000 * | −0.103 |

| MAF23 | 15 | 6 | 0.533 | 0.683 | 0.626 | 0.023 | 0.138 |

| VH34 | 15 | 6 | 0.800 | 0.749 | 0.686 | 0.921 | −0.041 |

| BM4505 | 15 | 4 | 0.800 | 0.733 | 0.656 | 0.215 | −0.071 |

| AF5 | 15 | 3 | 0.267 | 0.301 | 0.271 | 0.009 | 0.105 |

| BM1225 | 15 | 7 | 0.667 | 0.809 | 0.750 | 0.000 * | 0.079 |

| CSSM43 | 15 | 5 | 0.467 | 0.759 | 0.686 | 0.013 | 0.231 |

| RT1 | 15 | 5 | 0.600 | 0.575 | 0.520 | 0.104 | −0.026 |

| TEAXAN-15 | 15 | 4 | 0.867 | 0.671 | 0.586 | 0.252 | −0.150 |

© 2012 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, J.; Li, C.; Yang, J.; Luo, Z.; Tang, S.; Li, F.; Li, C.; Liu, B.; Jiang, Z. Isolation and Characterization of Cross-Amplification Microsatellite Panels for Species of Procapra (Bovidae; Antilopinae). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 8805-8818. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms13078805

Chen J, Li C, Yang J, Luo Z, Tang S, Li F, Li C, Liu B, Jiang Z. Isolation and Characterization of Cross-Amplification Microsatellite Panels for Species of Procapra (Bovidae; Antilopinae). International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2012; 13(7):8805-8818. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms13078805

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Jing, Chunlin Li, Ji Yang, Zhenhua Luo, Songhua Tang, Feng Li, Chunwang Li, Bingwan Liu, and Zhigang Jiang. 2012. "Isolation and Characterization of Cross-Amplification Microsatellite Panels for Species of Procapra (Bovidae; Antilopinae)" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 13, no. 7: 8805-8818. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms13078805