Neurotrophic Effect of Citrus Auraptene: Neuritogenic Activity in PC12 Cells

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cultures of Rat Neurons

2.2. Cultures of PC12 Cells

2.3. Immunoblot Analysis

2.4. Assessment of Process Formation

3. Results and Discussion

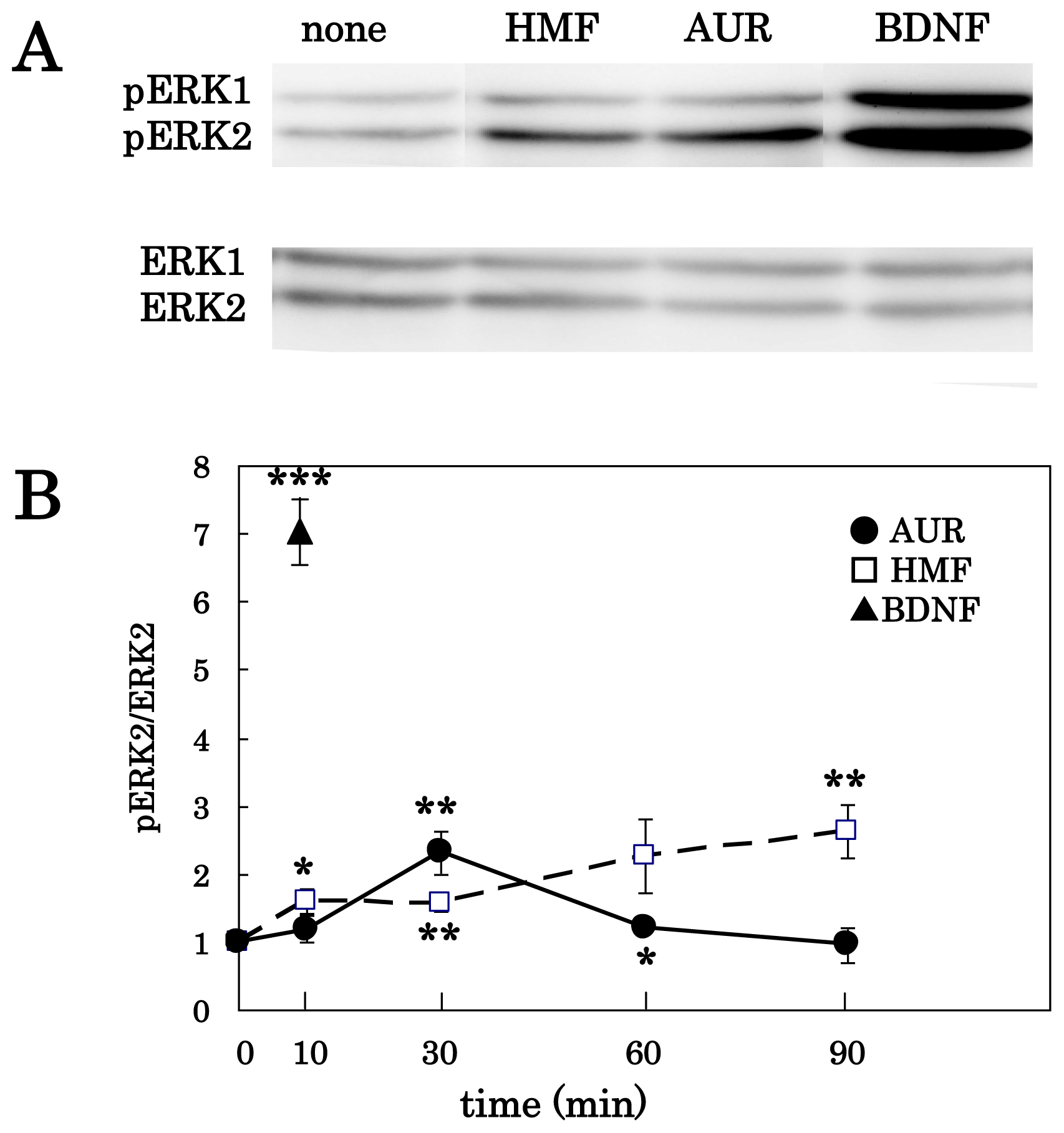

3.1. AUR-Induced ERK Activation in Cortical Neurons

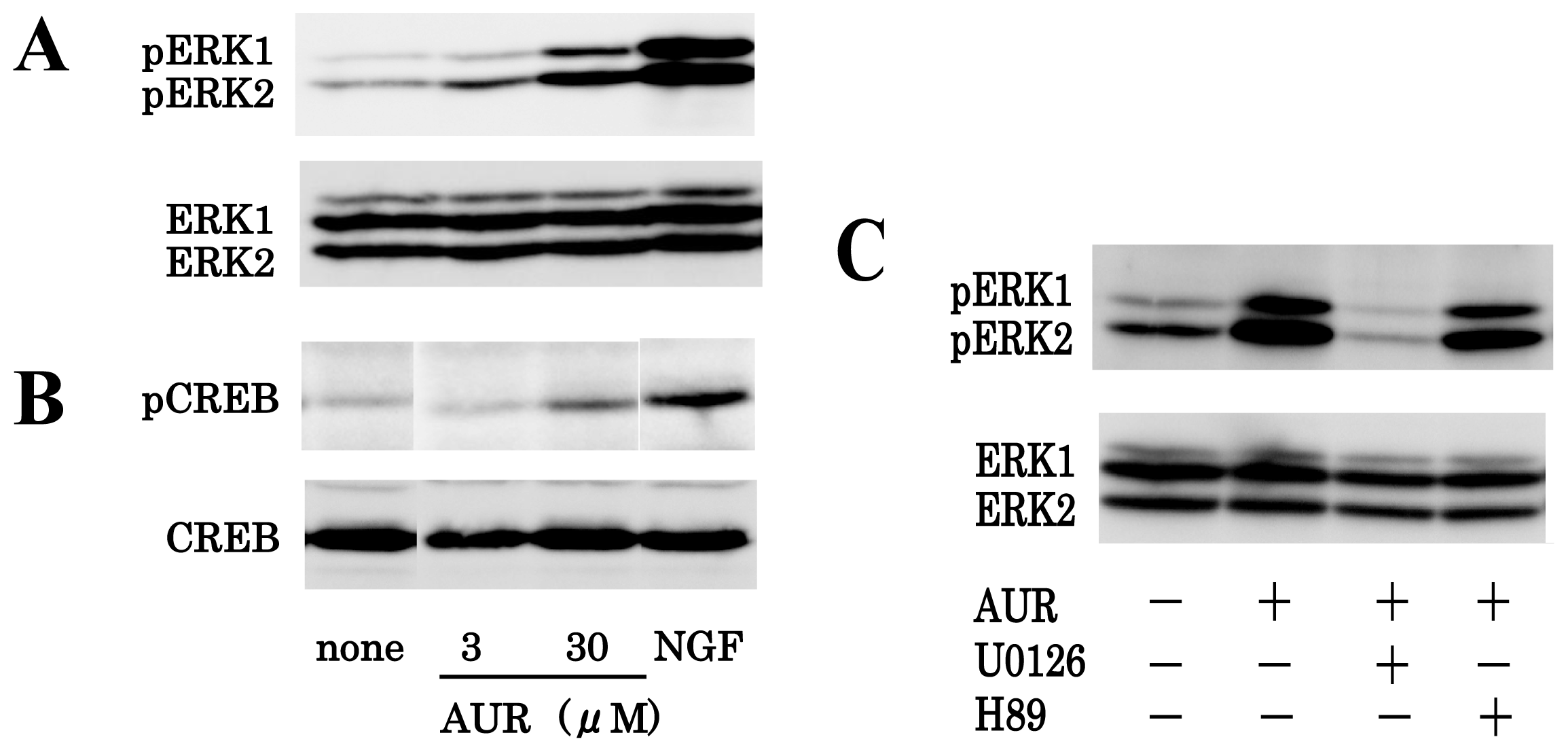

3.2. AUR-Induced ERK Activation in PC12 Cells

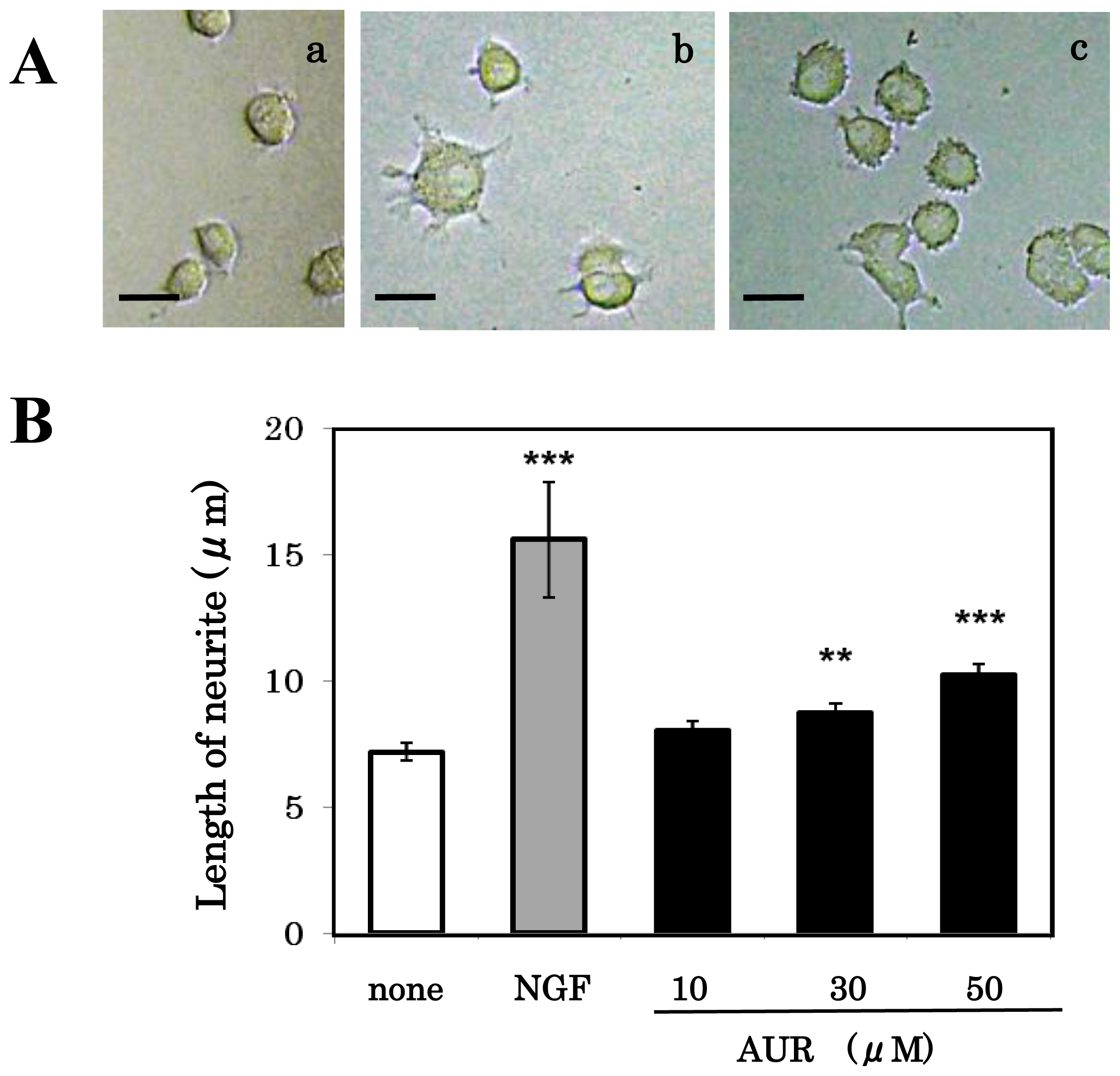

3.3. Effect of AUR on Neuronal Differentiation of PC12 Cells

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Samuels, I.S.; Karlo, J.C.; Faruzzi, A.N.; Pickering, K.; Herrup, K.; Sweatt, J.D.; Saitta, S.C.; Landreth, G.E. Deletion of ERK2 mitogen-activated protein kinase identifies its key roles in cortical neurogenesis and cognitive function. J. Neurosci 2008, 28, 6983–6995. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, J.P.; Sweatt, J.D. Molecular psychology: Roles for the ERK MAP kinase cascade in memory. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol 2002, 42, 135–163. [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa, Y.; Okuyama, S.; Amakura, Y.; Watanabe, S.; Fukata, T.; Nakajima, M.; Yoshimura, M.; Yoshida, T. Isolation and characterization of activators of ERK/MAPK from Citrus plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2012, 13, 1832–1845. [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa, K.; Kawasaki, A.; Yoshida, T.; Nesumi, H.; Nakano, M.; Ikoma, Y.; Yano, M. Evaluation of auraptene content in Citrus fruits and their products. J. Agric. Food Chem 2000, 48, 1763–1769. [Google Scholar]

- Murakami, A.; Matsumoto, K.; Koshimizu, K.; Ohigashi, H. Effects of selected food factors with chemopreventive properties on combined lipopolysaccharide- and interferon-γ-induced IκB degradation in RAW264.7 macrophages. Cancer Lett 2003, 195, 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Curini, M.; Carvotto, G.; Epifano, F.; Giannone, G. Chemistry and biological activity of natural and synthetic prenyloxycoumarins. Curr. Med. Chem 2006, 13, 199–222. [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata, K.; Murakami, A.; Ohigashi, H. Citrus auraptene targets translation of MMP-7 (matrilysin) via ERK1/2-dependent and mTOR-independent mechanism. FEBS Lett 2006, 580, 5288–5294. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, T.; Yasui, Y.; Ishigamori-Suzuki, R.; Oyama, T. Citrus compounds inhibit inflammationand obesity-related colon carcinogenesis in mice. Nutr. Cancer 2008, 60, 70–80. [Google Scholar]

- Takeda, K.; Utsunomiya, H.; Kakiuchi, S.; Okuno, Y.; Oda, K.; Inada, K.; Tsutsumi, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Kakudo, K. Citrus auraptene reduces Helicobacter pylori colonization of glandular stomach lesions in Mongolian gerbils. J. Oleo Sci 2007, 56, 253–260. [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi, N.; Kang, M.S.; Kuroyanagi, K.; Goto, T.; Hirai, S.; Ohyama, K.; Lee, J.Y.; Yano, M.; Sasaki, T.; Murakami, S.; et al. Auraptene, a Citrus fruit compound, regulates gene expression as a PPARα agonist in HepG2 hepatocytes. Biofactors 2008, 33, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Nagao, K.; Yamano, N.; Shirouchi, B.; Inoue, N.; Murakami, S.; Sasaki, T.; Yanagita, T. Effects of Citrus auraptene (7-geranyloxycoumarin) on hepatic lipid metabolism in vitro and in vivo. J. Agric. Food Chem 2010, 58, 9028–9032. [Google Scholar]

- Epifano, F.; Molinaro, G.; Genovese, S.; Ngomba, R.T.; Nicoletti, F.; Curini, M. Neuroprotective effect of prenyloxycoumarins from edible vegetables. Neurosci. Lett 2008, 443, 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- Trist, D.G. Excitatory amino acid agonists and antagonists: Pharmacology and therapeutic applications. Pharm. Acta Helv 2000, 74, 221–229. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, L.A.; Tischler, A.S. Establishment of a noradrenergic clonal line of rat adrenal pheochromocytoma cells which respond to nerve growth factor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1976, 73, 2424–2428. [Google Scholar]

- Traverse, S.; Gomez, N.; Paterson, H.; Marshall, C.; Cohen, P. Sustained activation of the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase cascade may be required for differentiation of PC12 cells. Biochem.J 1992, 288, 351–355. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, C.J. Specificity of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling: Transient versus sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. Cell 1995, 80, 179–185. [Google Scholar]

- Boss, V.; Roback, J.D.; Young, A.N.; Weisenhorn, D.M.; Medina-Flores, R.; Wainer, B.H. Nerve growth factor, but not epidermal growth factor, increase Fra-2 expression and alters Fra-2/JunD binding to AP-1 and CREB binding elements in pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells. J. Neurosci 2001, 21, 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, J.P.E.; Vauzour, D.; Rendeiro, C. Flavonoids and cognition: The molecular mechanisms underlying their behavioural effects. Arch. Biochem. Biophys 2009, 492, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Banno, Y.; Nemoto, S.; Murakami, M.; Kimura, M.; Ueno, Y.; Ohguchi, K.; Hara, A.; Okano, Y.; Kitade, Y.; Onozuka, M.; et al. Depolarization-induced differentiation of PC12 cells is mediated by phospholipase D2 through the transcription factor CREB pathway. J. Neurochem 2008, 104, 1372–1386. [Google Scholar]

- Sagara, Y.; Vanhnasy, J.; Maher, P. Induction of PC12 cell differentiation by flavonoids is dependent upon extracellular signal-regulated kinase action. J. Neurochem 2004, 90, 1144–1155. [Google Scholar]

- Okada, M.; Makino, A.; Nakajima, M.; Okuyama, S.; Furukawa, S.; Furukawa, Y. Estrogen stimulates proliferation and differentiation of neural stem/progenitor cells through different signal transduction pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci 2010, 11, 4114–4123. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.Z.; Boxer, D.S.; Latchman, D.S. Activation of the Bcl-2 promoter by nerve growth factor is mediated by the p42/p44 MAPK cascade. Nucleic Acids Res 1999, 27, 2086–2090. [Google Scholar]

- Vossler, M.R.; Yao, H.; York, R.D.; Pan, M.G.; Rim, G.S.; Stork, P.J. cAMP activates MAP kinase and Elk-1 through a B-Raf- and Rap1-dependent pathway. Cell 1997, 89, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Matta, S.G.; Yorke, G.; Roisen, F.J. Neuritogenic and metabolic effects of invididual gangliosides and their interaction with nerve growth factor in cultures of neuroblastoma and pheochromocytoma. Dev. Brain Res 1986, 27, 243–252. [Google Scholar]

- Nagase, H.; Yamakuni, T.; Matsuzaki, K.; Maruyama, Y.; Kasahara, J.; Hinohara, Y.; Kondo, S.; Mimaki, Y.T.; Sashida, Y.; Tank, A.W.; et al. Mechanism of neurotrophic action of nobiletin in PC12D cells. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 13683–13691. [Google Scholar]

- Nishina, A.; Sekiguchi, A.; Fukumoto, R.; Koketsu, M.; Furukawa, S. Selenazoles (selenium compounds) facilitate survival of cultured rat pheochromocytoma PC12 cells after serum-deprivation and stimulate their neuronal differentiation via activation of Akt and mitogen-activated protein kinase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun 2007, 352, 360–365. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.J.; Lee, H.J.; Choi, D.H.; Huang, H.S.; Lim, S.G.; Lee, M.K. Effect of scoparone on neurite outgrowth in PC12 cell. Neurosci. Lett 2008, 440, 14–18. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, K.-K.; Wu, M.-J.; Chen, P.-Y.; Huang, S.-W.; Chiu, S.-J.; Ho, C.-T.; Yen, J.-H. Curcuminoids promote neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells through MAPK/ERK- and PKC-dependent pathways. J. Agric. Food Chem 2012, 60, 433–443. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, H.-C.; Wu, M.-J.; Chen, P.-Y.; Sheu, T.-T.; Chiu, S.-P.; Lin, M.-H.; Ho, C.-T.; Yen, J.-H. Neurotrophic effect of Citrus 5-hydroxy-3,6,7,8,3′,4′-hexamethoxyflavone: Promotion of neurite outgrowth via cAMP/PKA/CREB pathway in PC12 cells. PLoS One 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2012 by the authors; licensee Molecular Diversity Preservation International, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).

Share and Cite

Furukawa, Y.; Watanabe, S.; Okuyama, S.; Nakajima, M. Neurotrophic Effect of Citrus Auraptene: Neuritogenic Activity in PC12 Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 5338-5347. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms13055338

Furukawa Y, Watanabe S, Okuyama S, Nakajima M. Neurotrophic Effect of Citrus Auraptene: Neuritogenic Activity in PC12 Cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2012; 13(5):5338-5347. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms13055338

Chicago/Turabian StyleFurukawa, Yoshiko, Sono Watanabe, Satoshi Okuyama, and Mitsunari Nakajima. 2012. "Neurotrophic Effect of Citrus Auraptene: Neuritogenic Activity in PC12 Cells" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 13, no. 5: 5338-5347. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms13055338