Progress in Studies on Rutaecarpine. II.—Synthesis and Structure-Biological Activity Relationships

Abstract

:1. Introduction

| Period | 1915–2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Numbers | 339 | 42 | 46 | 43 | 59 | 69 | 64 | 52 | 19 | 733 |

2. Synthesis of Rutaecarpine

2.1. Synthesis Using Tryptamine

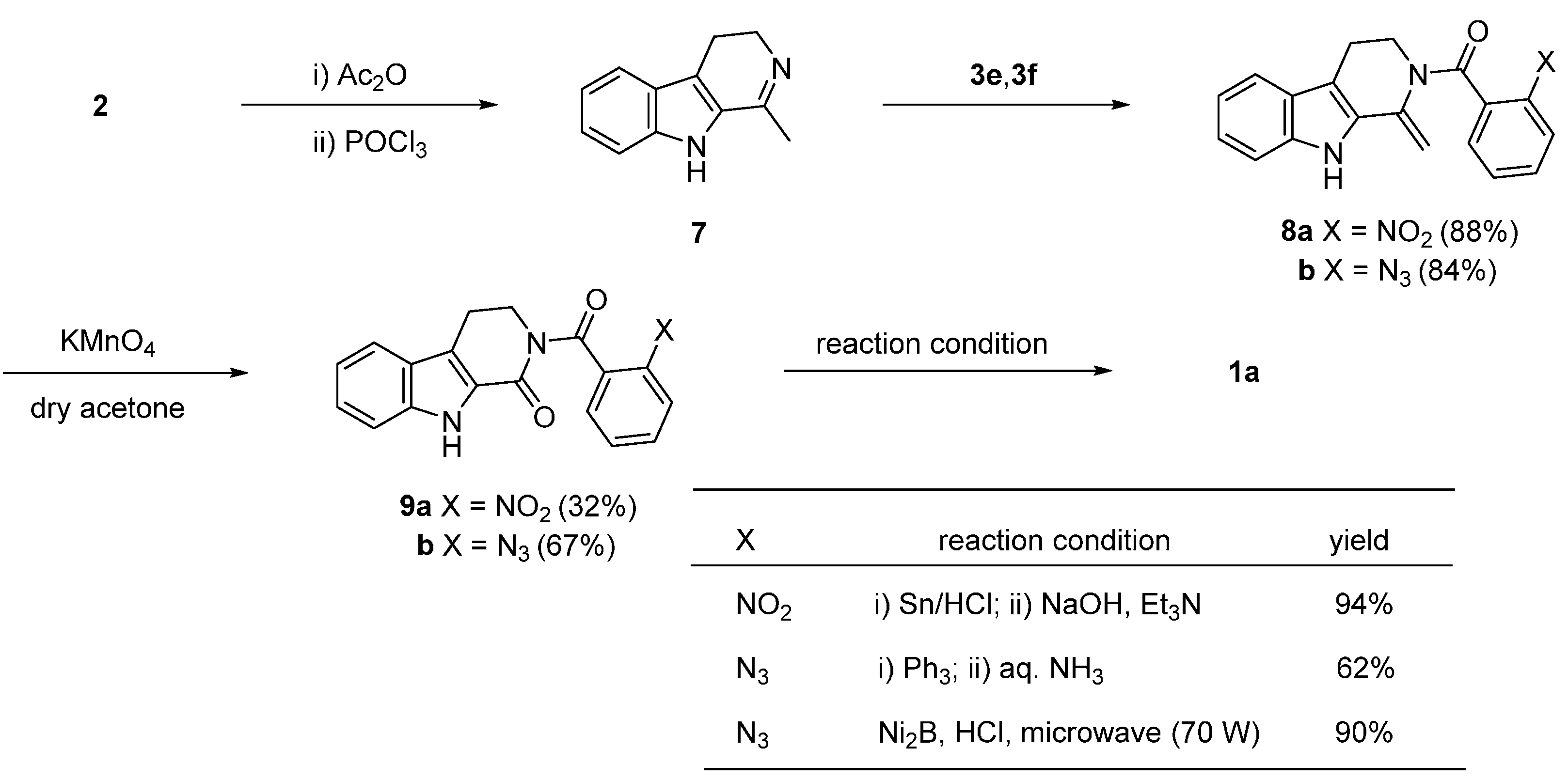

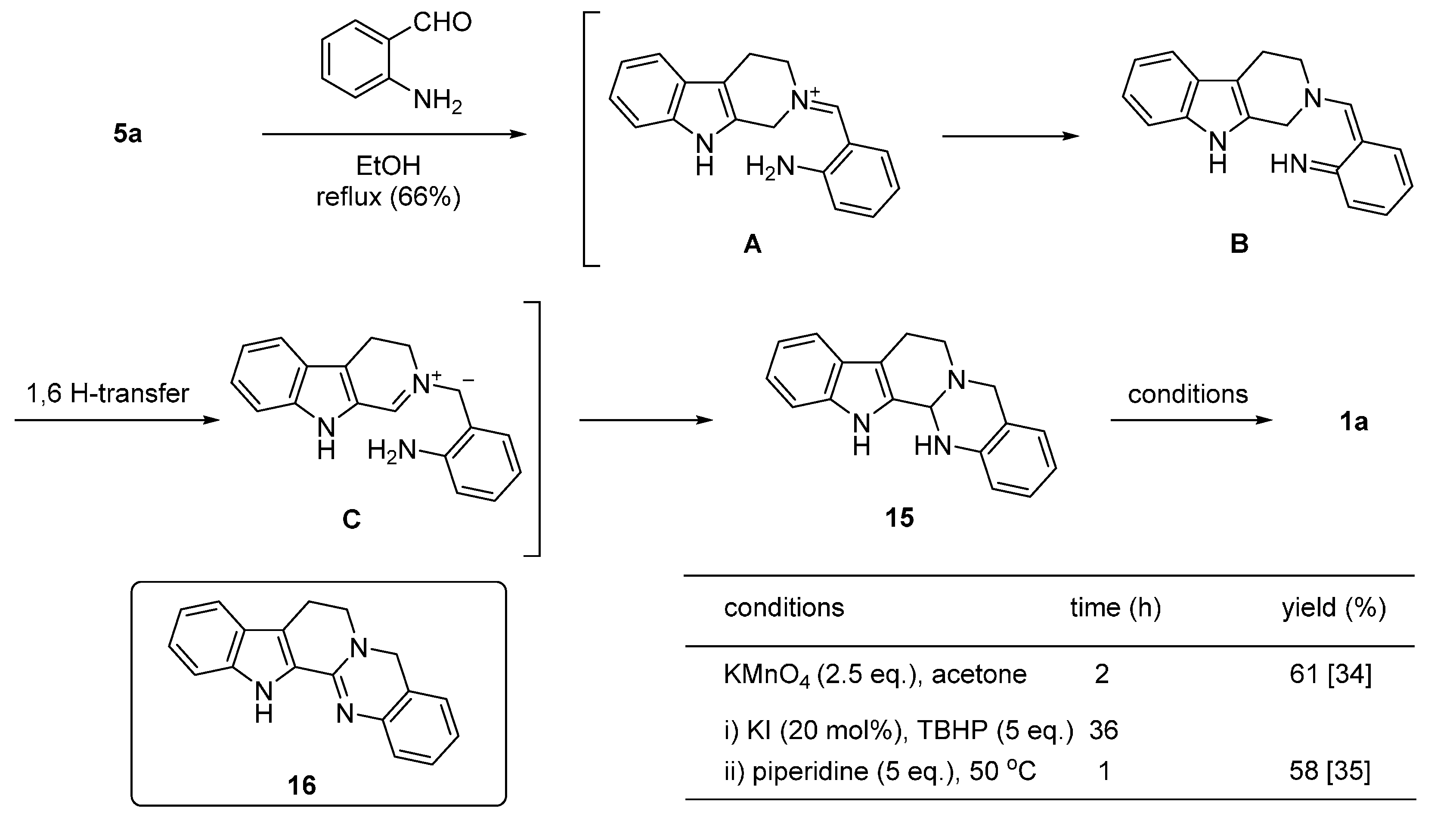

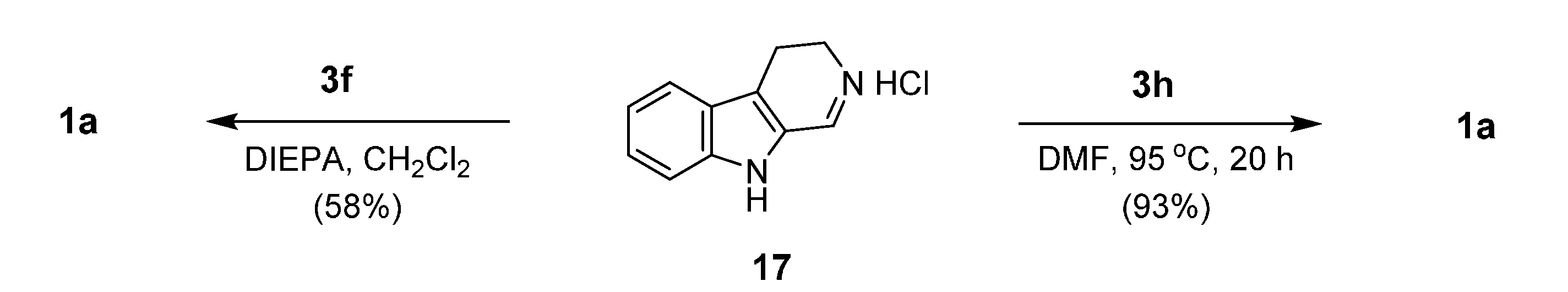

2.2. Synthesis Using Tetrahydro-β-Carboline

2.3. Miscellaneous

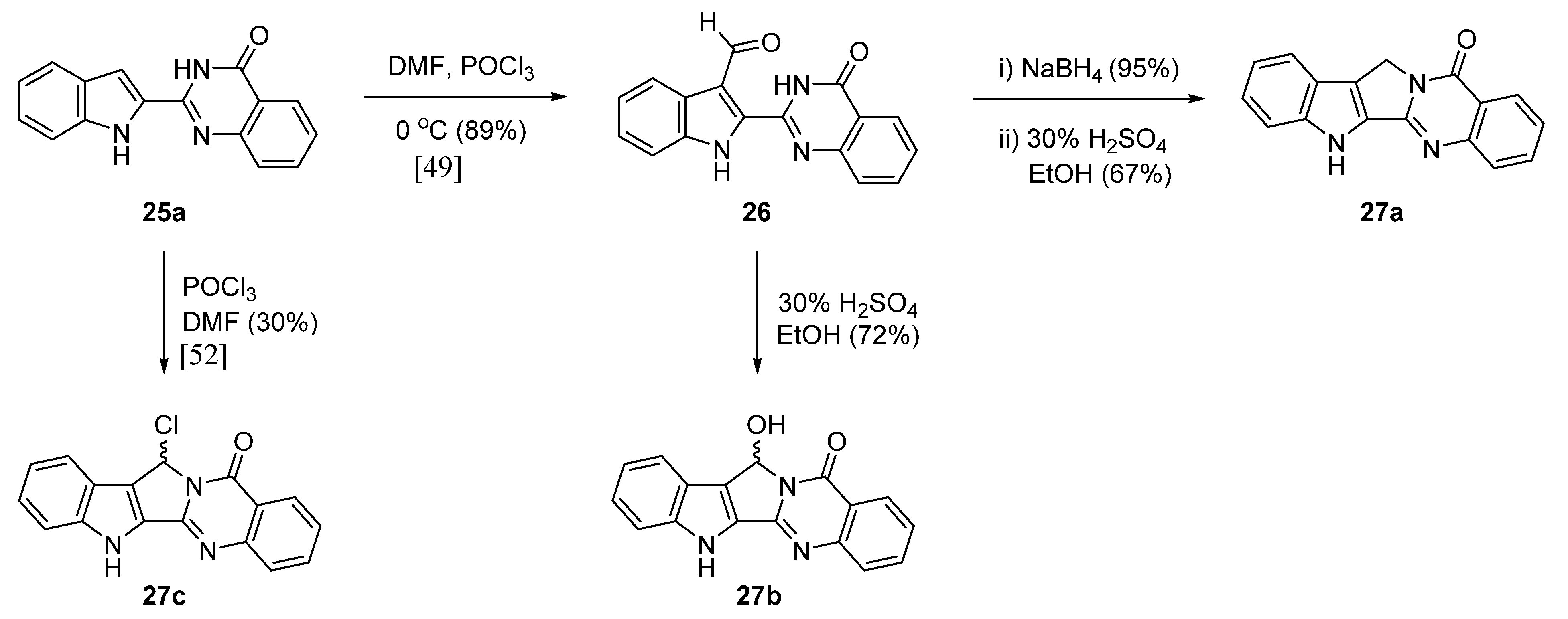

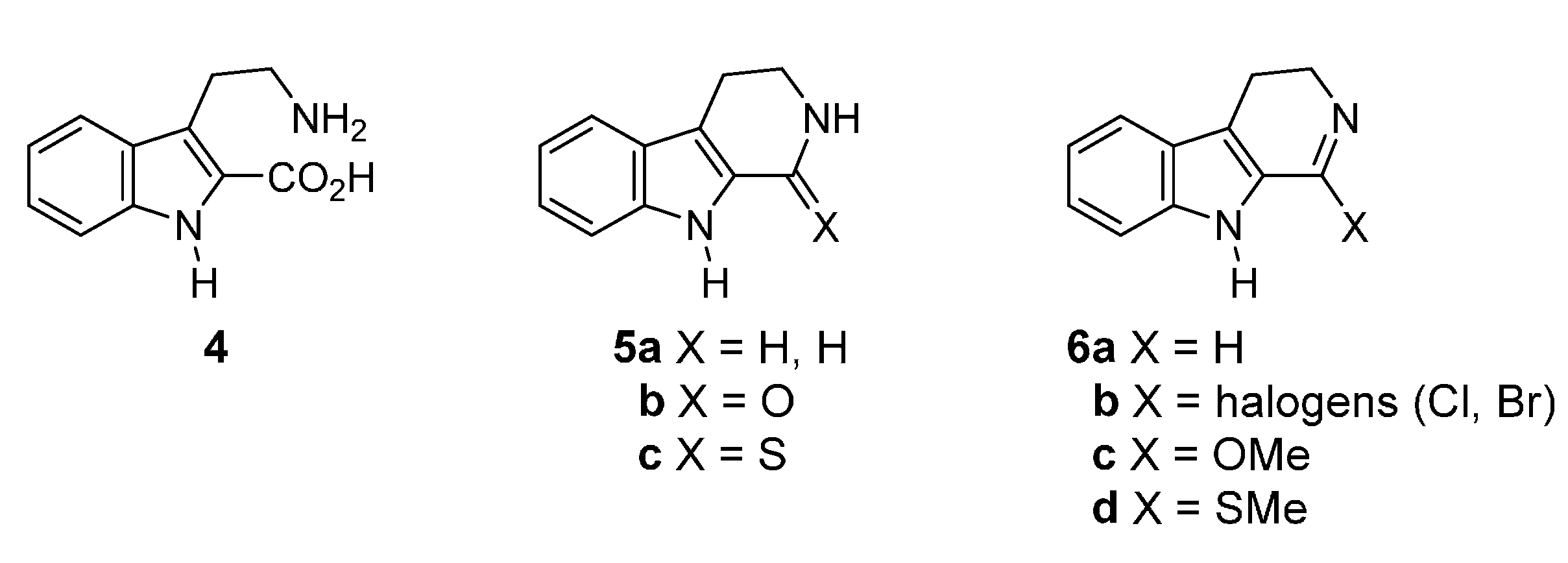

2.4. Synthesis of Bioisosteres and Hybrid Rutaecarpine Systems

3. Biological Properties

3.1. Antiplatelet Activity

| Compound | R1 | R2 | Aggregation (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inducer | ||||||

| ADP (0.22 μM) | Thrombin (0.1 unit∙mL−1) | A.A. a (100 μM) | Collagen (10 μg∙mL−1) | |||

| 1a | H | H | 99 b [56] | 85.7 c [28] | 85.2 c [28], 0 d [57] | 82.1 c [28], 22.1 c [57] |

| 1b [28] | H | 2,3-OCH2O- | 89.8 b | 0 e | ||

| 1c [28] | H | 3-Cl | 88.8 b | 0 e | 75.4 c | |

| 0.5% DMSO [28] | 88.2 | 90.1 | 88.5 | |||

| 1d [58] | H | 3-OH | 84.0 d | 0 e | 51.1 c | |

| 1e [58] | H | 3-OMe | 89.7 e | 0 f | 19.8 c | |

| aspirin (20 μg∙mL−1) [58] | 92.1 d | 0 e | 90.1 d | |||

| 1aa [57] | CH2CH2OH | H | 76 b | |||

| 1ab [57] | (CH2)3CO2H | H | 14 b | |||

| 1ac [57] | 3,4-(Me)2C6H3 | H | 88 b | |||

3.2. Vasodilator Activity

3.3. Cytotoxicity

3.3.1. Rutaecarpine Derivatives

3.3.2. Rutaecarpine-Isosteres and Hybrids

| SF-295 | HT-29 | A549/ATCC | NCI-H460 | OVCAR-4 | 786-0 | CCRF-CEM/HL-60 | N87 | HS-578T | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a (rutaecarpine) | 14.1 [72] | 31.6 [73] | 14.5 [63] | 18.9 [63] | 19.8 [74] | 8.41 [74] | 22.6 [63] | ||

| 1b (10,11-OCH2O-) [63] | >25.0 | 1.55 | 1.50 | 1.08 | >25.0 | 5.05 | |||

| 1d (3-OH) [70] | 11.94 | ||||||||

| 1e (10-OCH3) [63] | >25.0 | >25.0 | >25.0 | >25.0 | >25.0 | ||||

| 1f (11-OCH3) [63] | 0.75 | 1.38 | >25.0 | 0.31 | 1.59 | ||||

| 1g (10-Br) [72] | 8.62 | 16.3 b | 6.43(11.1) c | ||||||

| 1h (1-OH) [73] | 7.39 | 10.43 | 10.1 [74], 8.34 [70] | 8.38 [74] | |||||

| 1i [7-OH(β)] [74] | 10.1 | 23.2 | |||||||

| 1j [7-OH(β), 8-OH(α)] [74] | 13.7 | 14.1 | |||||||

| 1k [7-OH(β), 8-OCH3(α) [74] | 7.82 | 22.3 | |||||||

| 1l [7-OH(β), 8-OEt(α)] [74] | 8.31 | 27.9 | |||||||

| 1m (2-Cl) [64] | 5.62 | 22.4 | 21.6 d | ||||||

| 1n (12-F) [64] | 1.26 | 8.4 | 3.18 d | ||||||

| 1o (11,12-diCl) [75] | 0.15 |

| Compound | X | R1 | R2 | R3 | U251 | H522 | UACC62 | SKOV3 | DU145 | ACHN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28a | S | H | H | H | >100 | >100 | 7 | 10 | >100 | >100 |

| 28b | S | Cl | H | H | 53 | 74 | 2 | 12 | 12 | 2 |

| 28c | S | SCH3 | CH3 | CO2Et | >100 | >100 | 7 | 20 | 2 | 13 |

| 28d | S | F | H | H | >100 | >100 | 7 | 17 | 1 | 46 |

| 28e | N | Br | CH3 | H | 26 | 33 | 9 | 14 | 34 | 20 |

| 28f | O | Cl | t-Bu | H | 11 | - | 14 | 8 | 15 | 2.4 |

| 29a | - | H | H | H | 0.02 | 37 | >100 | 3 | 0.2 | 20 |

| 29b | - | SCH3 | H | H | 3 | 35 | 17 | 13 | 15 | 0.08 |

| 29c | - | SOCH3 | H | H | 7 | >100 | >100 | 27 | 0.1 | 2 |

| 29d | - | Br | H | H | 5 | 59 | >100 | >100 | 32 | 1 |

| 29e | - | Cl | H | H | 2.5 | 9 | >100 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 29f | - | Cl | H | CH3 | 6 | 10 | 7 | 11 | 2 | 1 |

| 29g | - | Br | H | CH3 | 0.3 | 18 | >100 | 3 | 3 | 0.4 |

| 29h | - | H | H | CH3 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 15 | 11 |

| 29i | - | H | NO2 | H | 3 | 3 | 2 | 12 | 3 | 3 |

| Compound | Cell Lines (GI50, μM) | Topo I Inhibition (%) | Topo II Inhibition (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HEK293 | MCF7 | DU145 | HCT116 | K562 | |||

| 1a | >50 | 19.57 | 31.65 | 33.89 | 25.77 | 1.20 | 1.25 |

| 1g | (see Table 3) | 79.54 | 35.43 | ||||

| 1c | NT | NT | NT | NT | NT | 84.36 | 69.51 |

| 30a | 36.57 | 11.42 | 27.54 | 9.94 | 25.38 | NA | 45.38 |

| 30b | >50 | 16.94 | 36.55 | 24.16 | 31.42 | 48.09 | 3.52 |

| 30c | >50 | 12.25 | 30.14 | 15.78 | 25.63 | 0.46 | 45.92 |

| 30d b | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 30e | >50 | 12.06 | 29.64 | 25.36 | 28.39 | 28.11 | 52.74 |

| etoposide c | 4.09 | 3.02 | 3.75 | 1.88 | 2.23 | 52.52 | - |

| camptothecin c | 5.16 | 4.22 | 3.22 | 0.38 | 1.05 | - | 63.41 |

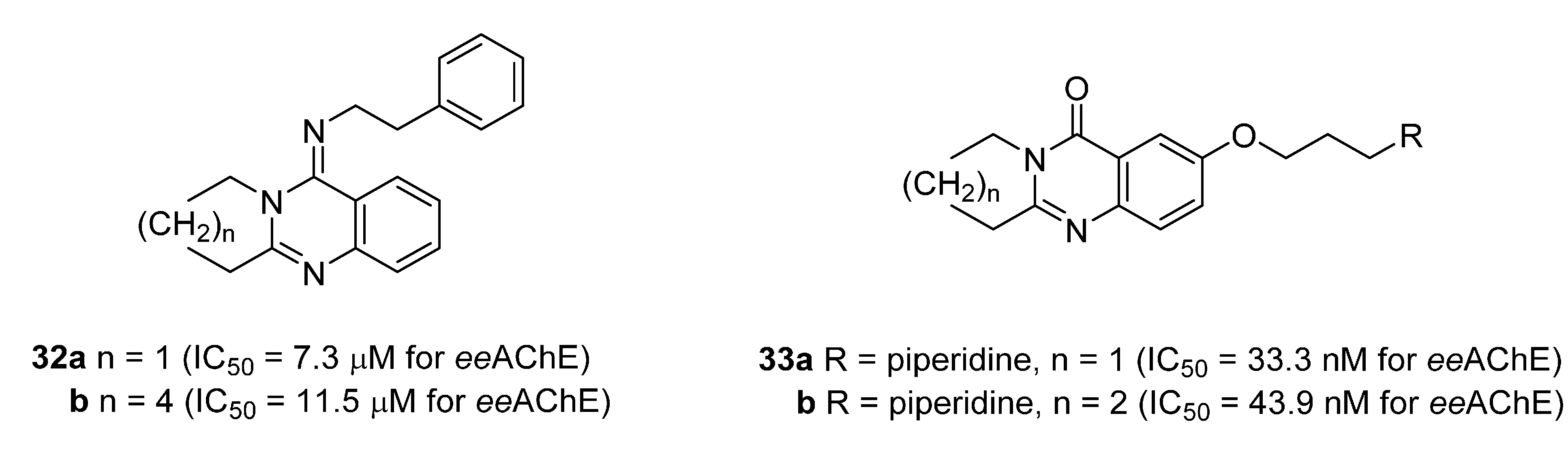

3.4. Inhibitory Activity on Acetylcholinesterase

| Compound | R | X | AChE Inhibition (nM) a | BuChE Inhibition (nM) b | Selectivity Index c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | H | O | >100,000 | >100,000 | |

| 1q | NHCOCH2NEt2 | O | 372.3 | 17,620 | 47.4 |

| 1r |  | O | 131.2 | 696.1 | 5.3 |

| 1s |  | O | 111.4 | 33,020 | 297.5 |

| 1t | NHCO(CH2)2NEt2 | O | 80.20 | 2848 | 35.5 |

| 1u |  | O | 29.24 | 844.5 | 28.9 |

| 1v |  | O | 21.40 | 2112 | 98.7 |

| 1w | H | H,H | 340 | 50 | 0.15 |

| tacrine | 222.7 | 29.98 | 0.1 | ||

| 31 [79] | 13,200 (37,800 [80], 6300 [83]) | 115,900 | 8.8 |

| Compound | R | N | AChE Inhibition (nM) a | BuChE Inhibition (nM) b | Selectivity Index c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11b [81] | NHCOCH2NEt2 | 57.09 (70.4 [82]) | 11,360 | 198.9 | |

| 11c [81] |  | 1 | 23.56 (59.3 [82]) | 428.2 | 18.2 |

| 11d [81] |  | 1 | 10.07 (70.0 [82]) | 5429 | 539.1 |

| tacrine [81] | 222.7 | 29.98 | 0.1 | ||

| 11e [82] |  | 2 | 13.90 | 14,900 | 1072 |

| 11f [82] |  | 2 | 51.00 | 24,000 | 471 |

| 11g [82] |  | 1 | 0.80 | 2451 | 3225 |

| 11h [82] |  | 1 | 0.61 | 1855 | 3092 |

| 11i [82] |  | 1 | 3.09 | 7300 | 2362 |

| 11j [82] |  | 2 | 2.30 | 4291 | 1858 |

| 11k [82] |  | 2 | 2.10 | 3488 | 1638 |

| 11l [82] |  | 2 | 14.30 | 6340 | 450 |

| 11m [82] |  | 3 | 3.90 | 4160 | 1056 |

| tacrine [82] | 108.0 | 33.4 | 0.3 |

| Compound | R | AChE Inhibition (nM) a | BuChE Inhibition (nM) b | Selectivity Index c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5b [84] | 83,380 | |||

| physostigmine [84] | 170 | 590 | 3.47 | |

| 25a [85] | H | >10,000 | >10,000 | |

| 25b [85] |  | 326.6 | 3103 | 9.50 |

| 25c [85] |  | 147.9 | 10,160 | 68.70 |

| 25d [85] |  | 20.98 | 7322 | 349.17 |

| tacrine [85] | 222.7 | 29.98 | 0.1 | |

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, A.L.; Chen, K.K. The constituents of Wuchuyin (Evodia rutaecarpa). J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 1933, 22, 716–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, J.F.; Chen, C.F.; Chow, S.Y. Pharmacological studies of Chinese herbs (9). Pharmacological effects of Evodia fructus. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 1981, 80, 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Asahina, Y.; Kashiwaki, K. Chemical constituents of the fruits of Evodia rutaecarpa. J. Pharm. Soc. Jpn. 1915, 1293. [Google Scholar]

- Asahina, Y.; Mayeda, S. Evodiamine and rutaecarpine, alkaloids of Evodia rutaecarpa. J. Pharm. Soc. Jpn. 1916, 871. [Google Scholar]

- Asahina, Y.; Fujita, A. Constitution of rutaecarpine. J. Pharm. Soc. Jpn. 1921, 863–869. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, J.H. Constituents of the Chinese drug Wu-Chu-Yu, Evodia rutaecarpa. Sci. Rec. (China) 1951, 4, 279–284. [Google Scholar]

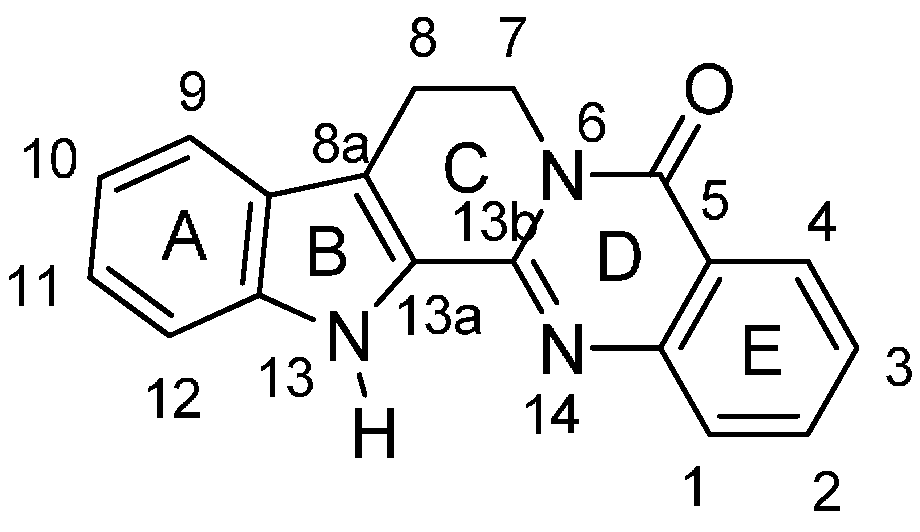

- Bergman, J. The quinazolinocarboline alkaloids. In The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Pharmacology; Brossi, A., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1983; Volume 21, pp. 29–54. [Google Scholar]

- Witt, A.; Bergman, J. Recent developments in the field of quinazoline chemistry. Curr. Org. Chem. 2003, 7, 659–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikelj, D. Product Class 13: Quinazolines. Sci. Synth. 2004, 16, 573–749. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.L.; Liu, J.L.; Ling, Y.P. Progress in the synthesis of rutaecarpine. Chin. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 26, 1437–1443. [Google Scholar]

- Kollenz, G. Product Class 10: Imidoylketenes. Sci. Synth. 2006, 23, 351–380. [Google Scholar]

- Mhaske, S.B.; Agrade, N.P. The chemistry of recently isolated naturally occurring quinazolinone alkaloids. Tetrahedron 2006, 62, 9787–9826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Guo, C.; Cheng, Z. Current advances in the study on rutaecarpine. Yaoxue Shijian Zazhi 2007, 25, 353–357. [Google Scholar]

- Shakhidoyatov, K.M.; Elmuradov, B.Z. Tricyclic quinazoline alkaloids: Isolation, synthesis, chemical modification, and biological properties. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2014, 50, 781–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, J.-R. Pharmacological effects of rutaecarpine, an alkaloid isolated from Evodia rutaecarpa. Cardiovasc. Drug Rev. 1999, 17, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.F.; Chiou, W.F.; Chou, C.J.; Liao, J.F.; Lin, L.C.; Wang, G.J.; Ueng, Y.F. Pharmacological effects of Evodia rutaecarpa and its bioactive components. Chin. Pharm. J. (Taiwan) 2002, 54, 419–435. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C.; Li, Y. Research progress in pharmacological actions of evodiamine and rutaecarpine. Chin. Pharmacol. Bull. 2003, 19, 1084–1087. [Google Scholar]

- Long, M.I.; Zhang, Y.M.; He, L.P.; Zeng, Q. Pharmacology of rutaecarpine. Jiefangjun Yaoxue Xuebao 2008, 24, 528–531. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, S.; Hu, C. Pharmacological effects of rutaecarpine as a cardiovascular protective agent. Molecules 2010, 15, 1873–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayakumar, T.; Sheu, J.R. Cardiovascular pharmacological actions of rutaecarpine, a quinazolinocarboline alkaloid isolated from Evodia rutaecarpa. J. Exp. Clin. Med. 2011, 3, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Meng, Y.; Wang, Q.; Yang, B.; Kuang, H. Study of the pharmaceutical effects and material basis of Fructus evodiae. Chin. Arch. Tradit. Chin. Med. 2011, 29, 2415–2417. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Gao, Y. Advances in modulation of cytochrome P-450 by Chinese herbal medicine. Zhong Cao Yao 2003, 34, 477–479. [Google Scholar]

- Ueda, J.; Ohsawa, K. Determination of main components in oriental pharmaceutical decoctions and extract preparations by ion-pair high-performance liquid chromatography. J. Tohoku Pharm. Univ. 2002, 49, 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.H.; Son, J.K.; Jeong, B.S.; Jeong, T.C.; Chang, H.W.; Lee, E.S.; Jahng, Y. Progress in the studies on rutaecarpine. Molecules 2008, 13, 272–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

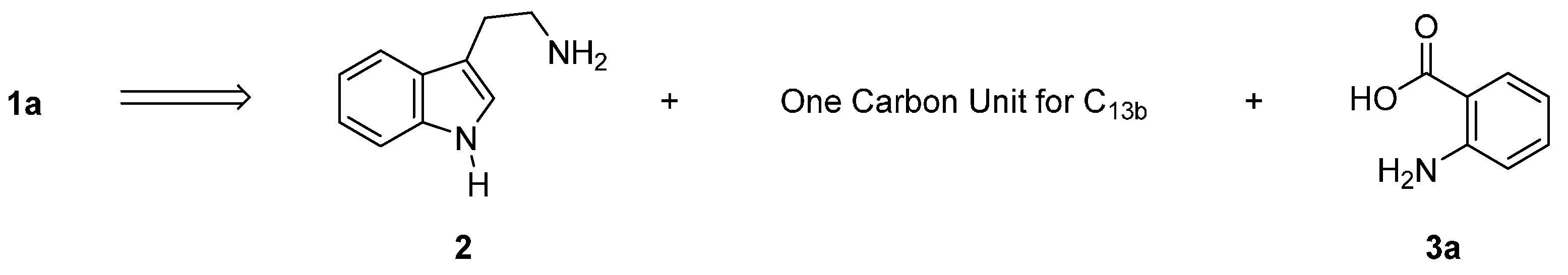

- Asahina, Y.; Irie, T.; Ohta, T. Synthesis of rutaecarpine. II. J. Pharm. Soc. Jpn. 1927, 543, 51–52. [Google Scholar]

- Asahina, Y.; Manske, R.H.F.; Robinson, R. A synthesis of rutaecarpine. J. Chem. Soc. 1927, 1708, 1708–1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Liu, C.K.; Chiang, Y.L.; Cheng, Y.Y. One-pot reductive-cyclization as key step for the synthesis of rutaecarpine alkaloids. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 481–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Liu, C.K.; Cheng, Y.Y.; Teng, C.M. A new and facile synthesis of rutaecarpine alkaloids. Heterocycles 2009, 78, 1047–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, A.; Reddy, M.K.; Reddy, T.S.; Santos, L.S.; Shankaraiah, N. Total synthesis of rutaecarpine and analogues by tandem azido reductive cyclization assisted by microwave irradiation. Synlett 2011, 1, 61–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

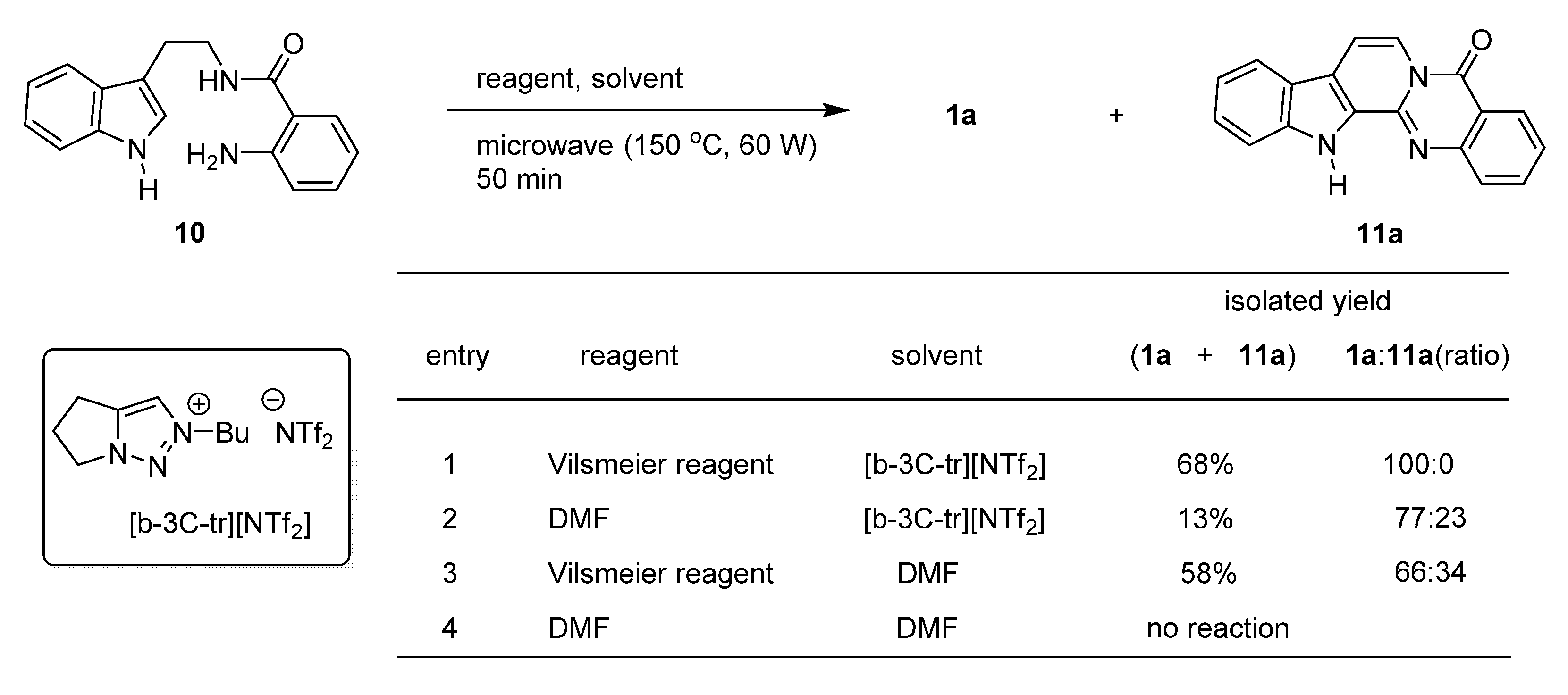

- Tseng, M.C.; Cheng, H.T.; Shen, M.J.; Chu, Y.H. Bicyclic 1,2,3-triazolium ionic liquids: Synthesis, characterization, and application to rutaecarpine synthesis. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 4434–4437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, K.R.; Raghunadh, A.; Mekala, R.; Meruva, S.B.; Pratap, T.V.; Krishna, T.; Kalita, D.; Laxminarayana, E.; Prasad, B.; Pal, M. Glyoxylic acid in the reaction of isatoic anhydride with amines: A rapid synthesis of 3-(un)substituted quinazolin-4(3H)-ones leading to rutaecarpine and evodiamine. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 6004–6006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

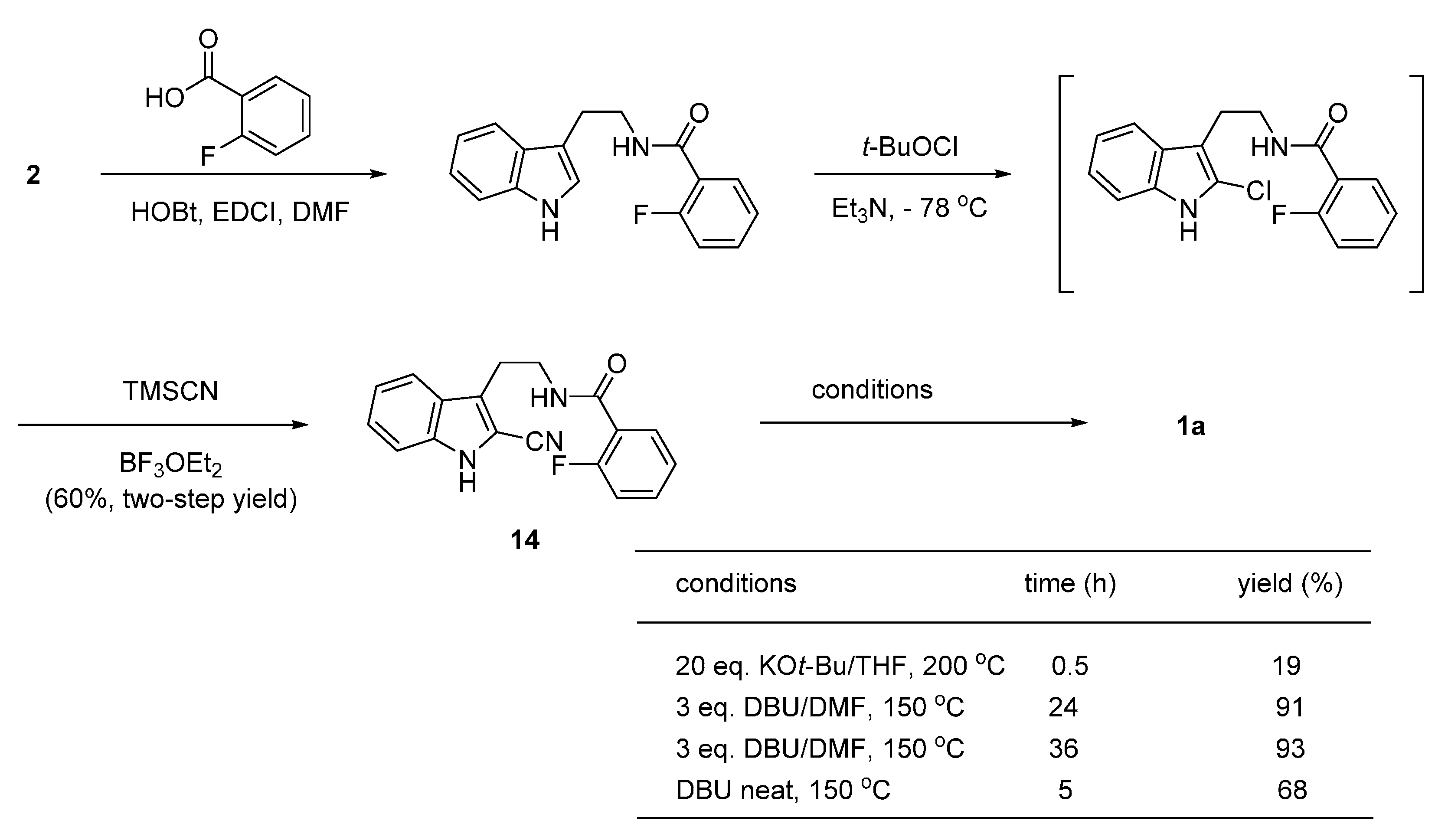

- Peterson, I.N.; Crestey, F.; Kristensen, J.L. Total synthesis of ascididemin via anionic cascade ring closure. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 9092–9094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

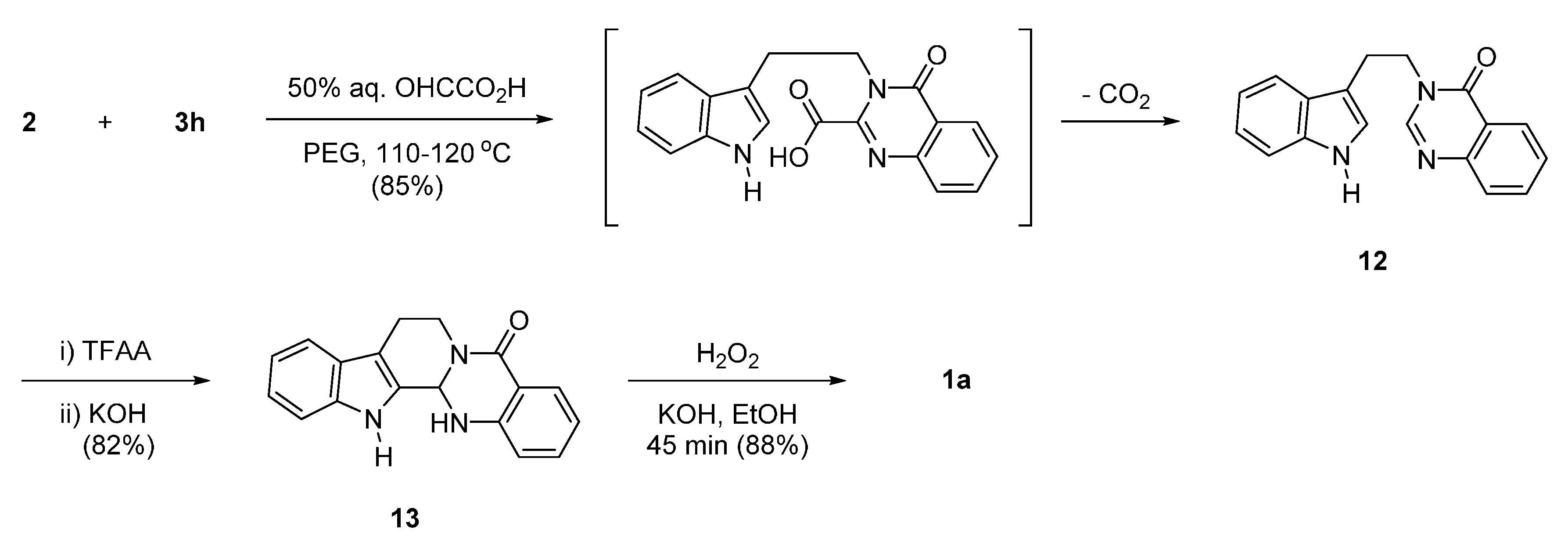

- Liang, L.N.; An, R.; Huang, T.; Xu, M.; Hao, X.J.; Pan, W.D.; Liu, S. A simple approach for the synthesis of rutaecarpine and its analogs. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015, 56, 2466–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; De, C.K.; Mal, R.; Seidel, D. α-Amination of nitrogen heterocycles: Ring-fused aminals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 416–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richers, M.T.; Zhao, C.; Seidel, D. Selective copper(II) and potassium iodide catalyzed oxidation of aminals to dihydroquinazoline and quinazolinone alkaloids. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2013, 9, 1194–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richers, M.T.; Deb, I.; Platonova, Y.A.; Zhang, C.; Seidel, D. Facile access to ring-fused aminals via direct a-amination of secondary amines with o-aminobenzaldehydes: Synthesis of vasicine, deoxyvasicine, deoxyvasicinone, mackinazolinone, and rutaecarpine. Synthesis 2013, 45, 1730–1748. [Google Scholar]

- Möhrle, H.; Kamper, C.; Schmid, R. Eine neue Synthese von Rutaecarin. Arch. Pharm. 1980, 313, 990–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, B.A.; Kaneda, K.; Martin, S.F. Multicomponent assembly strategies for the synthesis of diverse tetrahydroisoquinoline scaffolds. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 4542–4545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, G.; Roos, D.; Patricia Stadtmüller, P.; Decker, M. A simple heterocyclic fusion reaction and its application for expeditious syntheses of rutaecarpine and its analogs. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014, 55, 3607–3609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

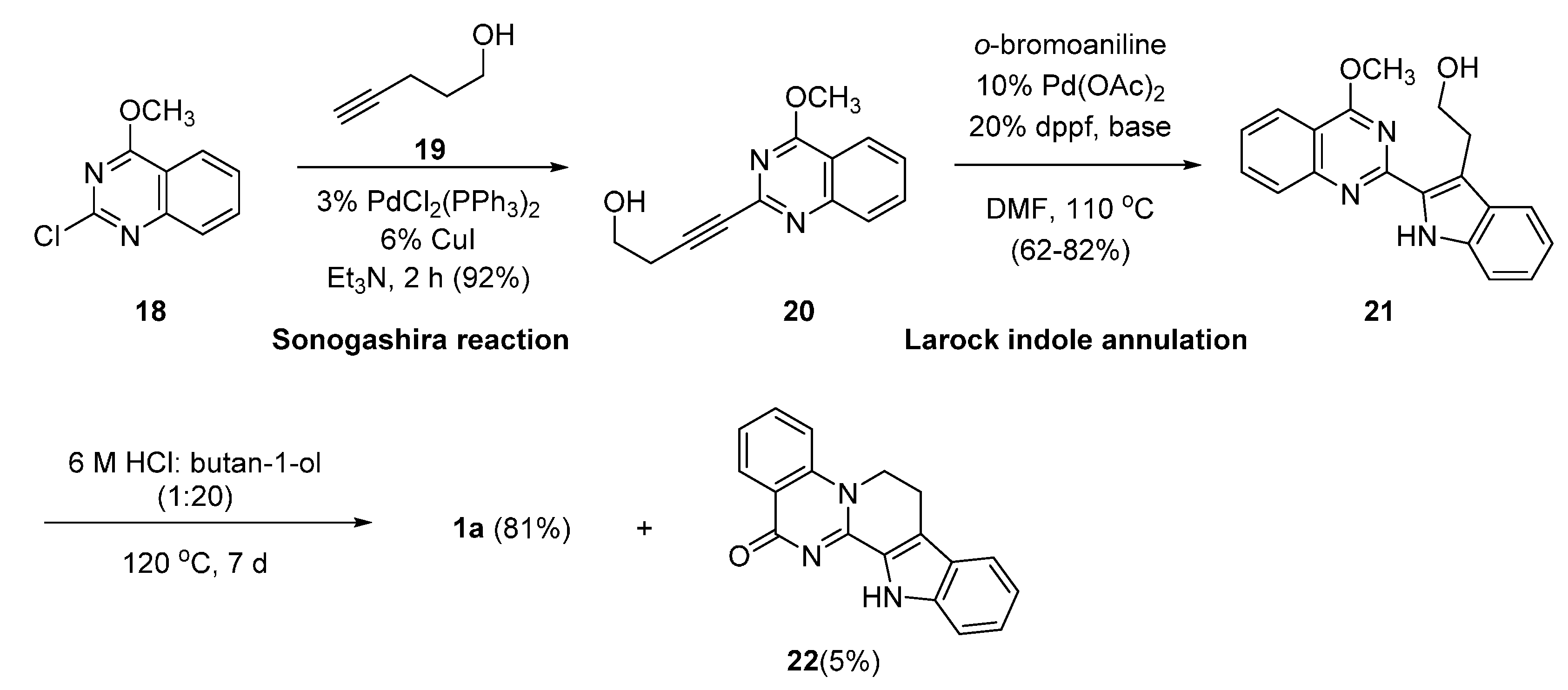

- Larock, R.C.; Yum, E.K. Synthesis of indoles via palladium-catalyzed heteroannulation of internal alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 6689–6690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Bannister, T.D. Sequential Sonogashira and Larock indole synthesis reactions in a general strategy to prepare biologically active β-carboline-containing alkaloids. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 6124–6127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kametani, T.; Loc, C.V.; Higa, T.; Koizumi, M.; Ihara, M.; Fukumoto, K. Iminoketene cycloaddition. 2. Total syntheses of arborine, glycosminine, and rutecarpine by condensation of iminiketene with amides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977, 99, 2306–2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergman, J.; Bergman, S. Studies of rutaecarpine and related quinazolinocarboline alkaloids. J. Org. Chem. 1985, 50, 1246–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, C.; Chiba, T.; Kasai, K.; Miwa, C. A short synthesis of rutecarpine and/or vasicolinone from 2-chloro-3-(indol-3-yl)ethylquinazolin-4(3H)-one: Evidence for the participation of the spiro intermediate. Heterocycles 1985, 23, 1385–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanta, P.K.; Kim, K. A Short Synthesis of quinazolinocarboline alkaloids rutaecarpine, hortiacine, euxylophoricine A and euxylophoricine D from methyl N-(4-chloro-5H-1,2,3-dithiazol-5-ylidene)anthranilates. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002, 43, 3993–3996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harayama, T.; Hori, A.; Serban, G. Concise synthesis of quinazoline alkaloids, luotonins A and B, and rutaecarpine. Tetrahedron 2004, 60, 10645–10649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, W.R.; Elsegood, M.R.J.; Stein, T.; Weaver, G.W. Radical reactions with 3H-quinazolinones: Synthesis of deoxyvasicinone, mackinazolinone, luotonin A, rutaecarpine, and tryptanthrin. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2007, 5, 103–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

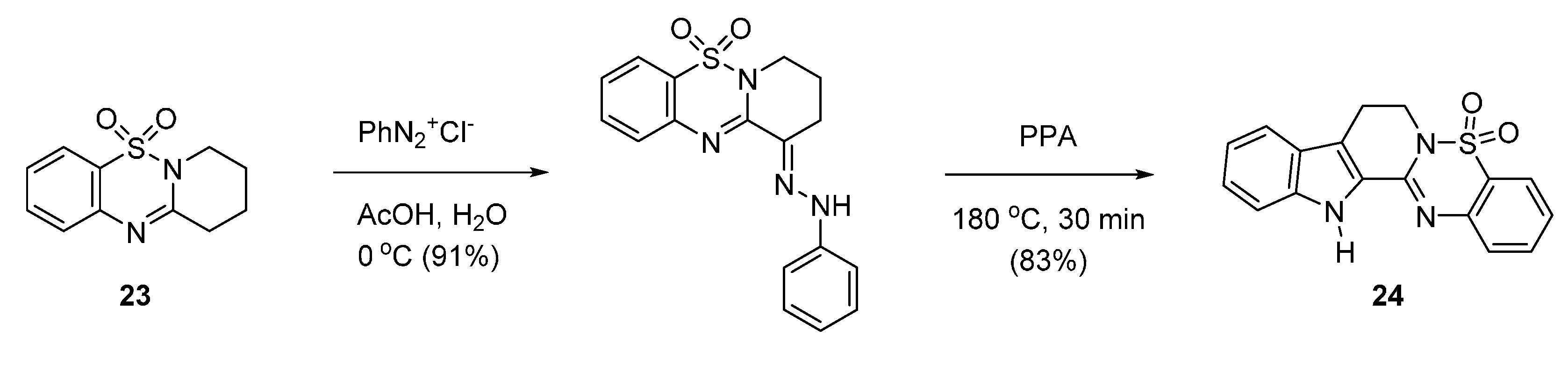

- Bubenyák, M.; Takács, M.; Blazics, B.; Rácz, A.; Noszál, B.; Püski, L.; Kökösi, J.; Hermecz, I. Synthesis of bioisosteric 5-sulfa-rutaecarpine derivatives. ARKIVOC 2010, 11, 291–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bubenyák, M.; Pálfi, M.; Takács, M.; Béni, S.; Szökö, É.; Noszál, B.; Kökösi, J. Synthesis of hybrid between the alkaloids rutaecarpine and luotonins A, B. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008, 49, 4937–4940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.Z.; Hano, Y.; Nomura, T.; Chen, Y.J. Two new pyrroloquinzolinoquinoline alkaloids from Peganum nigellastrum. Heterocycles 1997, 46, 541–546. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, J.U.; Cha, H.C.; Jahng, Y. Recent advances in the studies on luotonins. Molecules 2011, 16, 4861–4833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.C.; Zeng, X.Y.; He, Y.; Liu, H.; Wang, B.; Zhou, H.; Chen, J.W.; Liu, P.Q.; Gu, L.Q.; et al. Rutaecarpine analogues reduce lipid accumulation in adipocytes via inhibiting adipogenesis/lipogenesis with AMPK activation and UPR suppression. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 2301–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.J.; Lee, S.J.; Lee, S.; Chae, S.; Han, M.D.; Mar, W.; Nam, K.W. Rutecarpine ameliorates bodyweight gain through the inhibition of orexigenic neuropeptides NPY and AgRP in mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2009, 389, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.N.; Liu, Q.; Xu, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, X.; He, X.B.; Zhu, N.Y.; Liu, J.K.; Wu, Y.X.; Li, Y.Z.; et al. Rutaecarpine suppresses atherosclerosis in ApoE−/−mice through up-regulating ABCA1 and SR-BI within RCT. J. Lipid Res. 2014, 55, 1634–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Feng, T.; Liu, P.; Liu, C.; Wang, X.; Li, D.; Li, N.; Chen, M.; Xu, Y.; Si, S. Optimization of rutaecarpine as ABCA1 up-regulator for treating atherosclerosis. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 884–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheu, J.R.; Hung, W.C.; Lee, Y.M.; Yen, M.H. Mechanism of inhibition of platelet aggregation by rutaecarpine, an alkaloid isolated from Evodia rutaecarpa. Eur. J. Phmacol. 1996, 318, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zheng, W.; Sang, H.; Chen, J. Chin. Synthesis and aggregation activities in vitro of rutaecarpine derivatives. Zhongguo Yaowu Huaxue Zazhi 2006, 16, 20–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sheen, W.S.; Tsai, I.L.; Teng, C.M.; Ko, F.N.; Chen, I.S. Indolopyridoquinazoline alkaloids with antiplatelet aggregation activity from Zanthoylum integrifoliolum. Planta Med. 1996, 62, 175–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiou, W.F.; Chou, C.J.; Liao, J.F.; Sham, A.Y.C.; Chen, C.F. The mechanism of the vasodilator effect of rutaecarpine, and alkaloid isolated from Evodia rutaecarpa. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1994, 257, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiou, W.F.; Liao, J.F.; Chen, C.F. Comparative study on the vasodilatory effects of three quinazoline alkaloids isolated from Evodia rutaecarpa. J. Nat. Prod. 1996, 59, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.J.; Deng, H.W.; Xiao, L.; Hu, J.P. The depressor and vasodilator effects of rutaecarpine are mediated by calcitonin gene-related peptide. Planta Med. 2003, 69, 125–129. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Hua, G.; Li, D.; Chen, J.; Li, Y.; Zhou, H.; Xie, Y. Synthesis and vasodilator effects of rutaecarpine analogues which might be involved transient receptor potential vanilloid subfamily, member 1 (TRPV1). Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 2351–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.M.; Chen, C.F.; Lee, K.H. Synthesis of rutaecarpine and cytotoxic analogs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1995, 5, 465–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahng, Y.; Kim, S.I.; Lee, E.S. Synthesis and cytotoxicities of rutaecarpine analogues. In Abstracts of Papers of the American Chemical Society, Proceedings of the 227th ACS National Meeting, Anaheim, CA, USA, March 28–April 1 2004; MEDI 146. American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA.

- Larsen, L.K.; Moore, R.E.; Patterson, G.M.L. β-Carbolines from the blue-green alga Dichothrix baueriana. J. Nat. Prod. 1994, 57, 419–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.L.; Moon, D.C.; Lee, J.S.; Woo, M.H.; Lee, E.S.; Jahng, Y.; Chang, H.W.; Lee, S.H.; Son, J.K. Cytotoxicity and DNA topoisomerase inhibitory activity of constituents isolated from the fruits of Evodia officinalis. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2006, 29, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.I.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, E.S.; Lee, C.S.; Jahng, Y. New topoisomerase inbihitors: Synthesis of rutaecarpine derivatives and their inhibitory activity against topoisomerases. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2012, 35, 785–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogasawara, M.; Matsubara, T.; Suzuki, H. Screening of natural compounds for inhibitory activity on colon cancer cell migration. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2001, 24, 720–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baruah, B.; Dasu, K.; Vaitilingam, B.; Mamnoor, P.; Venkata, P.P.; Rajagopal, S.; Yeleswarapu, K.R. Synthesis and cytotoxic activity of novel quinazolino-β-carboline-5-one derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004, 12, 1991–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, N.; Li, Z.L.; Li, D.H.; Sun, Y.T.; Shan, D.T.; Bai, J.; Pei, Y.H.; Jing, Y.K.; Hua, H.M. Quinolone and indole alkaloids from the fruits of Euodia rutaecarpa and their cytotoxicity against two human cancer cell lines. Phytochemistry 2015, 109, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Q.H.; Wu, L.J.; Tashiro, S.I.; Onodera, S.; Ikejima, T. Atypical apoptosis in L929 cells induced by evodiamine isolated from Evodia rutaecarpa. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2004, 6, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.M.; Lin, S.J.; Lin, L.C.; Kuo, Y.H. Antitumor agents. 2. Synthesis and cytotoxic evaluation of 10-bromorutaecarpine. Chin. Pharm. J. (Taiwan) 1999, 51, 219–225. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.J.; Huang, H.Y.; Duh, C.Y.; Chen, I.S. Cytotoxic constituents from the stem bark of Zanthoxylum pistaciiflorum. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2004, 51, 659–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhang, Y.B.; Yang, X.W. Indoloquinazoline alkaloids from Euodia rutaecarpa and their cytotoxic activities. J. Asian Nat. Prod. Res. 2011, 13, 977–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, K.; Bracher, F. Cytotoxic hybrids between the aromatic alkaloids bauerine C and rutaecarpine. Z. Naturforsch. B 2007, 62, 1313–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costes, N.; le Deit, H.; Michel, S.; Tillequin, F.; Koch, M.; Pfeiffer, B.; Renard, P.; Leonce, S.S.; Guilbaud, N.; Kraus-Berthier, L.; et al. Synthesis and cytotoxic and antitumor activity of benz[b]pyran[3,2-h]acridine-7-one analogues of acronycine. J. Med. Chem. 2000, 43, 2395–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michel, S.; Gaslonde, T.; Tillequin, F. Benzo[b]acronycine derivatives: A novel class of antitumor agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2004, 39, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

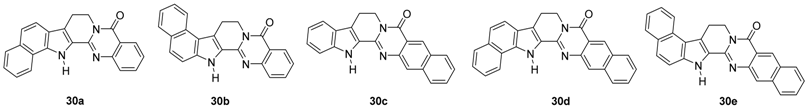

- Hong, Y.H.; Lee, W.J.; Lee, S.H.; Son, J.K.; Kim, H.L.; Nam, J.M.; Kwon, Y.; Jahng, Y. Synthesis and biological properties of benzo-annulated rutaecarpines. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2010, 33, 1704–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.Y.; Cha, M.R.; Choi, C.W.; Kim, Y.S; Lee, B.H.; Ryu, S.Y. Cholinesterase inhibitors isolated from the fruits extract of Evodia officinalis. Korean J. Pharmacogn. 2012, 43, 122–126. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.H.; Kim, S.H.; Choi, W.; Lee, Y.L.; Kim, J.S.; Kang, S.S.; Suh, Y.H. Novel anticholinesterase and antiamnesic activity of dehydroevodiamine, a constituent of Evodia rutaecarpa. Planta Med. 1996, 62, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

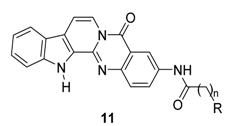

- Wang, B.; Mai, Y.C.; Li, Y.; Hou, J.Q.; Huang, S.L.; Ou, T.M.; Tan, J.H.; An, L.K.; Li, D.; Gu, L.Q.; et al. Synthesis and evaluation of novel rutaecarpine derivatives and related alkaloids derivatives as selective acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 45, 1415–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Yao, P.F.; Chen, S.B.; Huang, Z.H.; Huang, S.L.; Tan, J.H.; Li, D.; Gu, L.Q.; Huang, Z.S. Synthesis and evaluation of 7,8-dehydrorutaecarpine derivatives as potential multifunctional agents for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 63, 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decker, M. Novel inhibitors of acetyl- and butyrylcholinesterase derived from the alkaloids dehydroevodiamine and rutaecarpine. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 40, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fadaeinasab, M.; Hadi, A.H.A.; Kia, Y.; Basiri, A.; Murugaiyah, V. Cholinesterase enzymes inhibitors from the leaves of Rauvolfia reflexa and their molecular docking study. Molecules 2013, 18, 3779–3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z.; Wang, B.; Hou, J.Q.; Huang, S.L.; Ou, T.M.; Tan, J.H.; An, L.K.; Li, D.; Gu, L.Q.; Huang, Z.S. 2-(2-Indolyl-)-4(3H)-quinazolines derivates as new inhibitors of AChE: Design, synthesis, biological evaluation and molecular modelling. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2013, 28, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decker, M.; Krauth, F.; Lehmann, J. Novel tricyclic quinazolinimines and related tetracyclic nitrogen bridged compounds as cholinesterase inhibitors with selectivity on butylcholinesterase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 1966–1977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decker, M. Homobivalent quinazolinimines as novel nanomolar inhibitors of cholinesterases with dirigible selectivity toward butyrylcholinesterase. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 5411–5413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sugimoto, H.; Iimura, Y.; Yamaishi, Y.; Yamatsu, K. Synthesis and structure-activity relationships of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: 1-Benzyl-4-[(5,6-dimethoxy-1-oxoindan-2-yl)methylpiperidine hydrochloride and related compounds. J. Med. Chem. 1995, 38, 4821–4829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, I.; Ibrar, A.; Zaib, S.; Ahmad, S.; Furtmann, N.; Hameed, S.; Simpson, J.; Bajorath, J.; Iqbal, J. Active compounds from a diverse library of triazolothiadiazole and triazolothiadiazine scaffolds: Synthesis, crystal structure determination, cytotoxicity, cholinesterase inhibitory activity, and binding mode analysis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2014, 22, 6163–6173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2015 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Son, J.-K.; Chang, H.W.; Jahng, Y. Progress in Studies on Rutaecarpine. II.—Synthesis and Structure-Biological Activity Relationships. Molecules 2015, 20, 10800-10821. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules200610800

Son J-K, Chang HW, Jahng Y. Progress in Studies on Rutaecarpine. II.—Synthesis and Structure-Biological Activity Relationships. Molecules. 2015; 20(6):10800-10821. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules200610800

Chicago/Turabian StyleSon, Jong-Keun, Hyeun Wook Chang, and Yurngdong Jahng. 2015. "Progress in Studies on Rutaecarpine. II.—Synthesis and Structure-Biological Activity Relationships" Molecules 20, no. 6: 10800-10821. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules200610800