1. Introduction

South Korean society, traditionally regarded as homogenous in terms of race and ethnicity, has been transforming into a more multicultural society (

Castles and Miller 2009). The number of immigrants in Korea has increased consistently with the accelerating pace of globalisation. Beginning with an influx of migrant workers in the late 1980s and continuing with a rapid increase in the number of married immigrants in the 2000s, approximately 2.0 million foreigners were reported to be residing in Korea as of 2016, representing 3.9 per cent of the total South Korean population of 51.3 million (

MOJ 2017).

Among other factors, this rapid expansion of immigrants was facilitated by an influx of migrant women through international marriage. This influx of female marriage migrants was primarily demand-driven and supported by the Korean government as a means of addressing certain social issues—including a low fertility rate and an imbalanced marriage market—that had a particularly strong impact on males in rural areas and/or with lower social status. As the number of female marriage migrants has rapidly risen, they have become a major target of social policies in Korea, which has led to public controversies regarding how to understand and build multiculturalism

1 in Korean society. As a designated target of social inclusion policy, multicultural families are prioritised targets of migrant policies and are covered by welfare policies that apply to citizens in general (

Kim 2008). However, this attention has also resulted in criticism by some researchers who argue that too much policy focus on multicultural families has resulted in biased policy allocation, to the detriment of other immigrant groups, such as foreign workers (

Kim 2016,

2008;

Seol 2005;

Seol and Han 2004).

Examining social exclusion not only provides insights into the different reasons why people are excluded but also (ultimately) can help policymakers determine how to abate or target exclusion (

Byrne 2005;

Hills et al. 2002;

Percy-Smith 2000). Adopting the concept of social exclusion as an analytical tool (

de Haan 2000) can help overcome the limits of traditional cash-transfer policy for the poor, which has mainly focused on material well-being. Instead, studying social exclusion enables the identification of the diverse causes of deprivation and vulnerability among the poor, induces the implementation of integrated social policies, and enables full participation in the community for all individuals (

Room 1999). As for the context of Korean society, by extending the policy scope beyond economic deprivation and analysing the social exclusion of multicultural families, their complex needs can be identified for policy purposes, which can lead to better designed and more comprehensive and customised policies that promote the integration of these families into Korean society.

This paper is structured as follows. First, we examine the current conditions of multicultural families in Korea, which will highlight the multidimensionality in their vulnerabilities and adversities. We then review the literature on social exclusion to gain a better understanding of the implications involved with applying this approach to the Korean case and to illuminate how the social exclusion approach is related to social policy for multicultural families. This literature review is followed by the empirical part of this paper that first identifies indicators for measuring social exclusion and then examines the social exclusion of multicultural families in Korea. Finally, the concluding section discusses social policy implications based on the results from the empirical analysis.

2. A Brief Overview and Social Policy for Multicultural Families in Korea

The term ‘multicultural family’ is defined by several domestic laws in Korea. According to the Multicultural Families Support Act, multicultural families are defined as those established by the marriage of a Korean-born national to a foreign spouse.

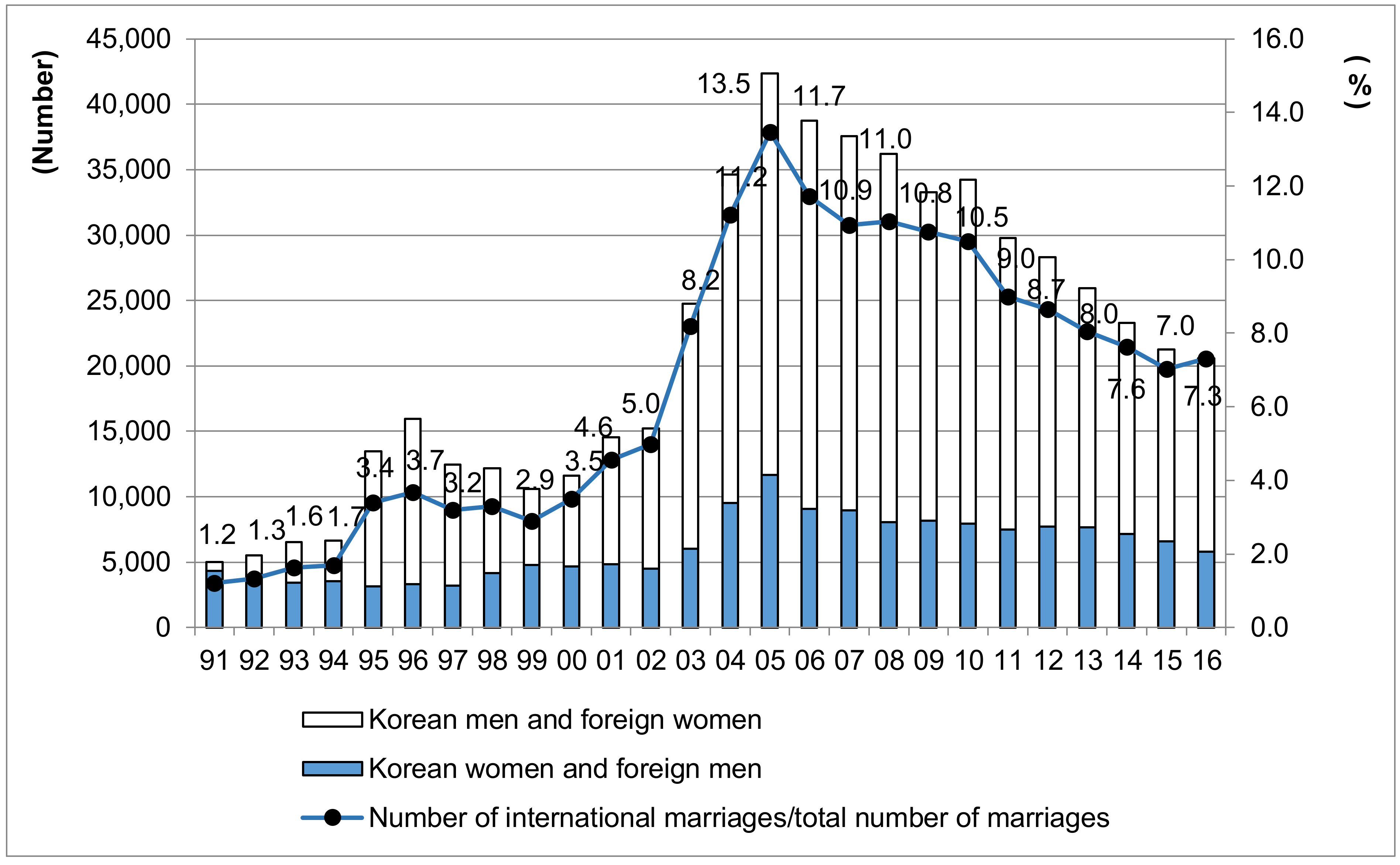

2 Figure 1 shows the rapid growth of multicultural families over the past twenty years. International marriages between Koreans and foreigners in the early 1990s constituted only approximately one per cent of all marriages, and the majority of these marriages were contracted between Korean women and foreign men. By contrast, the considerable increase in the number of international marriages during the 1990s and beyond resulted from marriages between foreign women and Korean men. Some groups of Korean men, particularly in rural areas, have had difficulties finding spouses due to social and demographic changes—gender imbalances in the marriage market resulting from younger females’ increasing tendency to migrate and consider international marriage options. Supported by international match-making performed by local governments, public policy money started to flow into local government-based rural bachelor marriage projects that significantly contributed to the increased interest of Korean men in international marriages (

Kim 2008). Moreover, full activities of private international matchmaking agencies accelerated the increase in the number of international marriages. Advised by private matchmaking agencies, the men who have difficulties finding a spouse in Korea get to be aware of the commercialisation of women in foreign countries. After a gradual increase during the mid-1990s, the number of international marriages began to increase dramatically during the first decade of new millennium. This number reached its peak in 2005, with more than 40,000 unions, corresponding to 13.5 per cent of total marriages. Since then, the number of international marriages appears to have gradually reached a plateau. Consequently, the rapid expansion of this type of international marriage in recent decades has led the Korean government to devote increased social policy attention to multicultural families.

The National Basic Livelihood Security System (hereafter NBLSS), a representative national public assistance system for Korean citizens, was reinforced in 2007 in order to provide benefits to female marriage immigrants and their families. In order to guarantee a minimum living standard for marriage immigrants, an “Exceptional Clause for Foreigners” was added to Article 5.2 of the National Basic Livelihood Security Act, according to which female marriage immigrants who are raising minor Korean children are eligible for the NBLSS even before naturalisation. As stipulated by the

Single-Parent Family Support Act and

Emergency Aid and Support Act, immigrants who raise minors either after the death of their Korean spouses or after divorce are also eligible for support. However, these marriage immigrants must not only pass a means test but also fulfil an extra condition, i.e., raise Korean minors, to establish eligibility for these public assistance programs.

3The Ministry of Gender Equality and Family (MOGEF), which oversees Korean multicultural family policy, has established a policy framework that provides services based on the settlement stage and life cycle of multicultural families and operates multicultural family support centres as service delivery systems at the local level (

MOGEF 2012). Although the social service framework of MOGEF may look quite comprehensive based on personal life cycle, it has often been criticised. A relatively strong focus on ‘young’ multicultural families and the wide distribution of similar programmes across different ministries provided by various support centres are the main reasons why some researchers have highlighted programme duplication and inefficiencies in social policies towards multicultural families (

Kim 2016;

Seol et al. 2005). For instance,

Kim (

2016, p. 92) found that marriage migrant women received approximately 59 percent of the national budget on foreign policies, while they were only 10 percent of the total number of migrants. Such concentration of welfare policies on marriage migrant women hinders the balanced treatment of migrants in Korea. Also,

Kim (

2014) criticised the ‘bureaucratic expansionism’ caused by the random usage of marriage migrant women in different policy agencies, resulting in the gender-blindness of policies.

Responding to such a strong social policy interest, central and local governments began conducting various surveys on multicultural families for use in subsequent empirical studies. These studies have played an important role in facilitating the introduction and expansion of related social policies aiming to address the social issues of multicultural families, such as their family life, economic situation, employment, domestic violence, and general quality of life (

Lee 2005;

Lee et al. 2006;

Seol et al. 2005;

KIHASA 2010). Some studies have also examined the status of marriage immigrants who utilised commercial matchmaking agencies, revealing the negative side effects and social problems involved in commercialised international marriages in Korea (

Kim 2008,

2009). The positive role of the multicultural family support centres enacted by the Multicultural Family Support Act in 2008 was also analysed, showing how they serve to integrate marriage migrant women into Korean society (

Chung and Yoo 2013). Furthermore,

Kim and Choi (

2016) showed the positive relationship between the use of social welfare services and life satisfaction of marriage migrant women and revealed the possible mediation effect of empowerment. Although these previous studies were meaningful for providing detailed information on the current status of multicultural families, they tend to focus on a small subgroup or a certain region due to either data constraints or their research purpose being aimed at understanding certain conditions faced by immigrants. This narrow focus consequently poses limitations in terms of representativeness and comparability. Moreover, these studies often portray immigrant women as passive victims requiring external assistance, ignoring their role as active agents in their own lives. The limitations of previous studies partially explain why social policies for multicultural families in Korea have primarily concentrated on limited material support for economic poverty, while overlooking the heterogeneity of their needs and various excluded situations.

In other words, without examining different individual needs, social policy for multicultural families leads to a discourse regarding limited public assistance and the duplication of social services; it is eventually designed at the central government level and rooted in a top-down policy approach. For this reason, unlike previous studies, we compare multicultural families with their Korean counterparts based on national representative survey data and adopt the concept of social exclusion in identifying the heterogeneous and differentiated needs of multicultural families not only compared with Korean families, but also compared with other multicultural families. In the empirical analyses, particular attention is paid to comparing the extent of social exclusion across different dimensions between multicultural and Korean families.

3. The Concept of Social Exclusion and Its Measurement

In this section, we briefly discuss how the conceptual and analytical approaches to social exclusion have evolved in Korea and briefly examine the extent to which focusing on social exclusion is related to social policy response.

During the 1980s, the European Union (EU) began to recognise the multidimensional properties of social exclusion after the publication of a number of studies that differed from previous research in their perspective on poverty (

Atkinson and Da Voudi 2000;

Berghman 1995;

European Commission 1998). Whereas the traditional notion of poverty primarily focused on the deficiency of economic and material resources, the concept of social exclusion broadened this scope to include employment, health, education, and social participation, among other factors. The EU’s embrace of the social exclusion concept has been based on efforts to overcome different forms of discrimination occurring across Europe (

Atkinson et al. 2002) and has led to the establishment of national action plans with common objectives. As a result, a social exclusion approach that is primarily based on poverty-related studies, exploring various characteristics of vulnerable groups, has become an important feature of the social integration paradigm adopted in Western Europe (

Muffels et al. 2002;

Pantazis et al. 2006).

Although the concept of social exclusion was originally defined as ‘a rupture of social bonds’ in 1980s France, where a greater value was placed on social solidarity, the United Kingdom has tended to highlight the consequences of exclusion as a form of discrimination, focusing on individual poverty and inequality on the basis of a neo-liberalist model (

Evans et al. 1995;

de Haan 2000;

Hills et al. 2002). In the late 1990s, the UK’s New Labour government actively adopted the concept of social exclusion and established a Social Exclusion Unit that embraced an employment-centred approach and primarily focused on exclusion in the labour market (

Evans et al. 1995;

Silver 1994).

In addition to national cases such as France and the UK, the concept of social exclusion has evolved into the National Action Plan on social inclusion (NAPincls) in several EU member states, which tend to emphasise a positive role of employment in overcoming the exclusion and focus on extremely marginalised individuals or groups. The increasing policy focus on social exclusion has become a major characteristic of European social policy, helping to create an understanding of the social problems that were not covered by the traditional concept of poverty (

Béland 2007;

Silver and Miller 2003) and to spread it beyond Europe through the mediation of international organisations.

4Despite criticism regarding the lack of a clear definition, the notion of social exclusion certainly provides a useful analytical tool that makes it possible to understand social inequality or deficiency across multiple dimensions (

Sen 2000).

Sen (

1983,

2000) considers social exclusion as a part of capability deprivation, which constrains a person’s real or substantive freedom to achieve functions. Being excluded from prevailing living standards can lead to further limitations to living a minimally decent life across various dimensions. Various efforts to operationalise and measure social exclusion have been observed both in the UK and in other countries within and beyond the EU. One example was the European indicators of social exclusion proposed by Atkinson and his colleagues (2002).

Atkinson (

1998) suggested three key elements to understand the notion of social exclusion: relativity, agency and dynamics. Excluding people based on relativity indicates that social exclusion is determined by comparing them with other people regarding a particular place and time. In addition, exclusion occurs in situations where people are being excluded, and understanding exclusion implies that the agency that excludes them is aware of that behaviour. In other words, exclusion has important implications for designing policy because there are excluded people and people who are excluding them. Exclusion focuses on others’ behaviours toward us, and it means that people who should be included are not only the members of groups excluded from policy benefits, but also the groups that are excluding them. Furthermore, dynamics means that being excluded implies not only whether people do not have jobs or income, but also that they have few prospects. In brief, social exclusion can occur over generations. The three pillars of Atkinson’s social exclusion theory are clearly described in a report by Atkinson and colleagues submitted to the European Parliament. The European Commission sought to develop social exclusion indicators under the leadership of the Social Protection Committee because it was obligated to develop indicators applicable to each member state. Consequently, it established 18 common indicators of social exclusion and poverty for its member states. Examples of these indicators are: poverty, income inequality, relative poverty, unemployment, long-term unemployment, life expectancy, subjective health, and poor health. By using these commonly defined and discussed indicators as described above, the European Union reached an important consensus for setting an agenda to overcome social exclusion (

Atkinson et al. 2002). Although some authors criticise it for overemphasising income poverty and labour market participation compared to social dimensions (

Levitas 2006), this proposal is regarded as pioneering work that extends the notion of social exclusion beyond simple measures of poverty and enables comparisons across the EU. For this reason, the social exclusion indicators used in this paper predominantly rely on the proposal of Aktinson and his colleagues, albeit with certain adjustments to account for Korea’s social conditions.

While an increasing number of studies in Korea address the definition of social exclusion, most studies introduce the definition theoretically and focus on a specific group in terms of empirical approaches. For example,

Yoon (

2005) examined the social exclusion of the working poor, considering dimensions such as property, consumption, education, participation in social relationships, and the employed sector;

Yoon and Lee (

2006) measured unemployment, poverty, housing, and the health conditions of North Korean refugees;

Kim (

2007) analysed the current status of social exclusion in Korea based on the European indicators of social exclusion; and

Kim (

2010) focused on diverse foreign newcomers in Korea and introduced indicators of social exclusion for foreign migrants. Overall, these studies do not extend beyond either introducing exclusion indicators or merely describing a specific target group or region, a limitation that may result in inconsistencies and contradictions in interpreting empirical results and in the provision of generalised social policy recommendations. In sum, the discourse on social exclusion in Korea has not become such a central social policy issue as it has been in European countries; however, it is being used to discover new vulnerable groups that were not captured in the traditional poverty discourse. As a result, the linkage between social exclusion discourse and social policy reform has been relatively weak in Korea and should be improved in the future on the basis of evidence-based research.

4. Methods

In this section, we introduce the datasets and indicators of social exclusion that are used in the analysis below. For the comparison, this paper used two nationwide representative datasets, one for immigrants and one for Korean nationals. For multicultural families, we used data collected from the National Multicultural Family Survey, which was the first and, until now, the only nationwide census survey in Korea exclusively targeting multicultural families.

5 The survey data included detailed information on housing, economic status, employment, marital status, family relations, health status, social networks, welfare status, and the individual needs of multicultural families. It also contained information on the individual characteristics of migrant family members, date of entry, as well as Korean language fluency.

For the Korean families, we used raw data from the National Welfare Survey on Living Conditions (

KIHASA 2015). The National Welfare Survey asked questions to 14,400 households about their general living conditions and collected extensive data on individuals’ socio-economic status, household type, income, property, and other information. The survey also included many questions concerning the welfare needs of individuals based on their socio-demographic characteristics. Because both data sets contained information on various dimensions of social deficiency and needs, they made it possible to compare poverty levels and social exclusion between the two groups. Although neither survey directly targeted social exclusion, they showed excellent comparability, as both surveys applied the same questions to measure exclusion-related indicators.

Before measurement, dimensions of social exclusion must be defined. As noted previously, this paper relies on the social exclusion indicators proposed by the EU, but it takes into account the specific social circumstances of Korean society suggested by previous studies on social exclusion in Korea. This study was based on six dimensions into which

Atkinson et al. (

2002) categorised the social exclusion indicators suggested by the member states of the European Union: financial, education, employment, health, housing, and social participation (

Atkinson et al. 2002, p. 45). Therefore, this study was intended to examine poverty status using income level as a key indicator of poverty. Employment was measured by unemployment status to indicate exclusion from work. Housing was defined as exclusion from a place where the reproduction of human life occurs and was perceived as incompleteness of the residential environment. Educational exclusion was applied to individuals who could not complete regular educational course at the standard age and was understood as a lack of educational opportunities. Regarding health, exclusion was a lack of medical protection and the state in which an individual could not maintain physical health for financial reasons. Social networks measured social isolation and alienation from social participation and identified the lack of a bond with family or friends. This study determined social exclusion variables based on those suggested by Atkinson for the European Union and an analysis was accordingly performed.

Table 1 lists the definition of social exclusion and the indicators for the six dimensions used in this paper: income, employment, housing, education, health, and social networks.

6 5. Results

This section consists of two parts. First, we examine the social exclusion of multicultural and Korean families and compare the results. In the second part, we examine the factors affecting the extent of social exclusion, focusing solely on multicultural families. This analysis aimed to identify the welfare needs that emerge from different dimensions of exclusion and to determine the implications for social policies addressing social exclusion in Korea.

5.1. Social Exclusion of Multicultural Families: A Comparative Perspective

We begin with a simple comparison of multicultural and Korean families for each dimension of social exclusion.

Figure 2 compares the proportions of those who are experiencing exclusion in each dimension for both family groups.

7Compared with Korean families, multicultural families generally experienced higher levels of exclusion across all dimensions. Poverty, which was here defined by the level of household income, was a key dimension of social exclusion. Multicultural families experienced income exclusion 1.8 times more frequently than their Korean counterparts. This result highlights the economic difficulties experienced by multicultural families and clearly co-relates with the higher unemployment rate among them. Multicultural families were excluded from employment opportunities nearly 4.7 times as often as Korean families were. A higher level of exclusion among multicultural families was also observed in dimensions such as health and social networks. The poverty that was prevalent among multicultural families offers an important explanation for why Korean immigration policy and social services have been particularly focused on this group of immigrants.

An individual’s social relationship or networks can be considered ‘social capital’ (

Bourdieu 1986;

Coleman 1990). Social capital is a resource that is often associated with an individual’s socio-economic status; lower socio-economic status is quite often linked with scarcer social resources (

Lin 1999;

Marsden 1987). For immigrants, social relationships can function as an important channel to facilitate their smooth adaptation to a new society. An absence of (or a substantially lower level of) social networks may hinder immigrants’ integration into a host society. With regard to the social network dimension, multicultural families were excluded approximately 2.6 times as frequently as Korean families were.

Measuring the multiplexity of social exclusion is one way to quantify the extent to which an individual experiences various dimensions of exclusion simultaneously. Multiple exclusion experiences are referred to as ‘deep exclusion’, which is defined by the Social Exclusion Unit (SEU) as exclusion manifest in more than one dimension (

Levitas et al. 2007, p. 29). Multiplexity is calculated by adding the degree of exclusion experienced by an individual across all dimensions considered. Therefore, the magnitude of multiplexity theoretically ranges from zero to the total number of dimensions being examined (e.g., six dimensions in this study). An analysis of multiplexity can reveal the extent of exclusion that individuals typically experience and thus provides information regarding how the degree and intensity of social exclusion varies with individual characteristics. A comparison of the multiplexity for multicultural and Korean families is presented in

Table 2.

According to the results, approximately 49 per cent of multicultural families and 72 per cent of Korean families reported no exclusion experience. However, one in five multicultural families indicated that they experienced two or more types of social exclusion, which confirms that multicultural families are exposed to a greater risk of social exclusion. The average degree of exclusion for multicultural families was approximately 0.78, whereas the average for Korean families was approximately 0.41. A comparison of these two figures indicates that multicultural families experience social exclusion approximately two times as frequently as Korean families do. This higher rate of social exclusion among multicultural families occurs, in part, because multicultural families are more likely to be found in lower income brackets than their non-multicultural counterparts (

KIHASA 2010;

Seol et al. 2005). This reflects the fact that those who prefer international marriage options are mostly the men who have difficulties finding spouses due to their social or economic difficulties and are willing to turn their eyes to international marriages.

8 5.2. Factors Affecting Social Exclusion in Multicultural Families

In this part, we examine the factors that affect the extent of social exclusion among multicultural families. Methodologically, the few previous studies that have attempted to identify the factors affecting social exclusion used logistic regression models, which examine the power of explanatory variables at predicting the probability of being excluded across each dimension, using those who are not excluded as a baseline (

Kim 2007;

Mannila and Reuter 2009). By contrast, this paper used ‘multiplexity’ as a dependent variable, which is advantageous because it can measure the overall degree of exclusion and can thus preserve more information than is possible with a binomial logit model.

As shown in

Table 2, multiplexity in this paper was a count variable that could have an integer value from 0 to 6 and had a non-normal distribution, with a disproportionately high frequency of the value zero, indicating ‘no exclusion at all’. One option to analyse this type of count data might be to use a linear or logistic regression model; however, linear regression is inadequate because it unrealistically presumes that the error term has a continuously probabilistic, normal distribution with the dependent variable; whereas, logistic regression may cause considerable information loss resulting from the reduction of count data into a binary variable (

Cameron and Trivedi 1998;

Long and Freese 2005). Therefore, we required a more sophisticated regression model to adequately handle the count data.

Among several possible models for addressing this type of count data, we used the zero-inflated Poisson (ZIP) regression model because the dependent variable of this analysis, the multiplexity of social exclusion, had a non-normal distribution and a high frequency of zero values (as shown in

Table 2). In general, the ZIP model is considered capable of handling data with excess zeroes better than the Poisson model by assuming two latent groups (

Cameron and Trivedi 2009;

Lambert 1992;

Long and Freese 2005). An individual in the

always zero group (Group A) takes the value of 0, with a probability of f

1(0), and

y = 0; whereas, an individual in the

not always zero group (Group ~A) may have a zero account, but there is a non-zero probability that

y takes on positive count values. This approach enables the ZIP model to handle this group in two ways: as a group member in a binary outcome that can be modelled using the logit model and as a member whose value is not always zero and whose probability can be determined by the Poisson regression (

Cameron and Trivedi 2009).

9 The advantage of the ZIP model lies in its ability to combine the strength of two models: the logit model that predicts the future probability of a certain incident and the count model that can identify the determining factors affecting the incident.

In the case of social exclusion, individuals in the always zero group had an outcome of zero, with no exclusion experiences; whereas, individuals in the not always zero group had positive counts that resulted from having at least one exclusion experience. Therefore, the ZIP model aiming to analyse the factors affecting social exclusion should proceed in two stages. The coefficients in the first count model represent risk factors affecting the examined incident as the level of accumulated social exclusion increases. The coefficients from the second logit model indicate that the probability of not experiencing an accumulation of exclusion is zero.

In addition to explanatory factors such as gender, age, marital status and social class

10 that are commonly used in social exclusion studies, the model also included living with a disabled family member, current health conditions, Korean language fluency

11 and number of social networks.

12The ZIP regression model results are shown in two parts in

Table 3. The first set of coefficients corresponds to cases in the non-zero category; whereas, the second set, labelled ‘inflated’, corresponds to the binary regression model. According to the results, female or older respondents tended to experience higher degrees of social exclusion than other individuals. With respect to the householder’s social class, the probability that an immigrant living with a self-employed or unskilled householder would experience social exclusion was as great as 2 times (e

0.684) or 1.7 times (e

0.533) higher, respectively, than the reference class of ‘high-grade professionals’. Furthermore, respondents living with disabled family members, as well as those in poor health, those who lacked social networks in the community and those who did not have adequate Korean language fluency tended to experience substantially higher levels of social exclusion.

The results of the logit model revealed that those who belonged to higher social classes were less likely to experience social exclusion. In general, respondents who were in better health or had fluent social ties in the community were less likely to experience social exclusion. Moreover, immigrants with greater Korean language fluency were less likely to be socially excluded. This result is consistent with the findings of other studies (i.e.,

OECD 2006) that have identified language proficiency as one of the essential instruments facilitating the integration of immigrants.

The result of the Vuong test was 7.38, which implies that the ZIP model was more appropriate in explaining the multiplexity of social exclusion than the Poisson model.

6. Discussion

This paper examined the current situation of multicultural families in Korea from the perspective of social exclusion by investigating multiple poverty-related dimensions rather than narrowly focusing on economic deficiency. This paper also aimed to contribute to finding a practical social policy solution to facilitate the integration of multicultural families into Korean society by identifying their heterogeneous social needs.

The results of this study indicated that multicultural families experience a higher level of social exclusion in general than Korean families. The extent of differences between the two family groups, however, varied across the dimensions of social exclusion. According to the results of the ZIP regression model, in which we examined the overall level of social exclusion among multicultural families based on their socio-demographic characteristics, immigrants were more likely to experience severe social exclusion if they were female, elderly or if they belonged to the lower social classes. Furthermore, low proficiency in the Korean language and a lack of social relationships in the community tended to exacerbate the degree and scope of their social exclusion. By contrast, individuals were less likely to experience social exclusion when they are in better health or had plenty of social networks. In addition, proficiency in Korean considerably decreased the risk of social exclusion among immigrants.

What social policy implications can we derive from the findings of this paper based on the social exclusion discourse? First, the social exclusion approach adopted in this paper was able to show the more vulnerable situations of multicultural families, which are exposed to a greater risk of exclusion than Korean families. We began this paper by discussing some criticisms of the policy focus on multicultural families in Korean migrant policy. However, we found evidence of a higher level of exclusion among multicultural families, even after controlling for the comparability of two datasets. Multicultural families were exposed to a substantially higher risk of social exclusion, and this finding empirically supports the necessity of expanding social policies that are available to this group of immigrants.

Second, welfare demands can be quite different depending on an individual’s socio-demographic background, which was made clear through the empirical analyses examining multiple dimensions of social exclusion. Although evidence supports the rationale for wider support for multicultural families, the empirical results of this study emphasize that social welfare demands among immigrants may vary considerably across the different dimensions of exclusion; therefore, the current social policy system that does not consider the multiple dimensions of exclusion may have difficulties in providing adequate support measures tailored to recipients’ needs. For example,

Figure 2 indicates that multicultural families experience a higher degree of exclusion, in terms of income or health, which in turn intensifies social exclusion on the whole. This circumstance emphasizes the importance of demand-oriented social policy to support multicultural families who are faced with a socio-economically impoverished residual situation. Moreover, the results in

Table 3 indicate that both immigrant social status and the socio-demographic characteristics of individuals may considerably affect the extent and scope of the social exclusion they experience, which demands a social policy that fully considers socio-demographic characteristics. According to this result, policymakers should not enforce a set of standardized immigrant policies in a typical top-down and provider-centred manner; rather, they should attempt to adopt consumer-centred immigrant policies that consider the needs of individual immigrants. This transition may also help to solve the duplication problem in social welfare services provided to female marriage migrants.

Third, regarding the factors affecting social exclusion, the accumulation of human capital emerges as one of the crucial factors for less exclusion and better integration. Given this recognition, immigrants should be encouraged much more than they currently are to enrich their human capital and skills, such as by participating in vocational training for job (re)location and economic self-reliance. Proactive labour market policies for multicultural families, and particularly those aimed at promoting the employment of female marriage immigrants who are willing to join in the labour market, can facilitate better integration of migrants into society. In addition, proficiency in the Korean language can substantially decrease their risk of being excluded and can otherwise make integration into Korean society easier. As the results of the ZIP model indicated, making diverse Korean language courses more accessible to immigrants could be an effective way of enhancing their capabilities for labour market participation, in particular, and for promoting better integration in general. While Korean language courses are already offered to immigrant women, the courses are aimed at a limited group and are offered by only a small number of local multicultural support centres. Therefore, we recommend expanding Korean language courses to reach wider groups of immigrants.

Finally, policy efforts should be made to expand the social networks of immigrants at the individual and regional level. As the results of the empirical analyses showed, exclusion from social networks among multicultural families appeared to hamper their seamless integration into Korean society. In addition, the denser that social networks are in a community, the less likely multicultural families are to experience social exclusion. Along with the immigrants’ own efforts to be better integrated, various community integration programmes, including those provided by regional institutions, must be strengthened to encourage them to join local communities. Community integration programmes can play a pivotal role in this respect, particularly in the early stages of the integration process, which means that the current social policy focusing on the individual level of marriage immigrants should be supplemented by policy measures targeting the community level. This paper examined social exclusion among multicultural families and compared them with Korean families using representative datasets. Methodologically, the ZIP model may be a new empirical approach to social exclusion because it allows measurement to be both excluded and not excluded, simultaneously. However, this paper used only cross-sectional data and could therefore not examine the dynamic process of exclusion, which is another strength of the social exclusion approach that should be investigated further in subsequent studies.