Uncovering Discursive Framings of the Bangladesh Shipbreaking Industry

Abstract

:1. Introduction

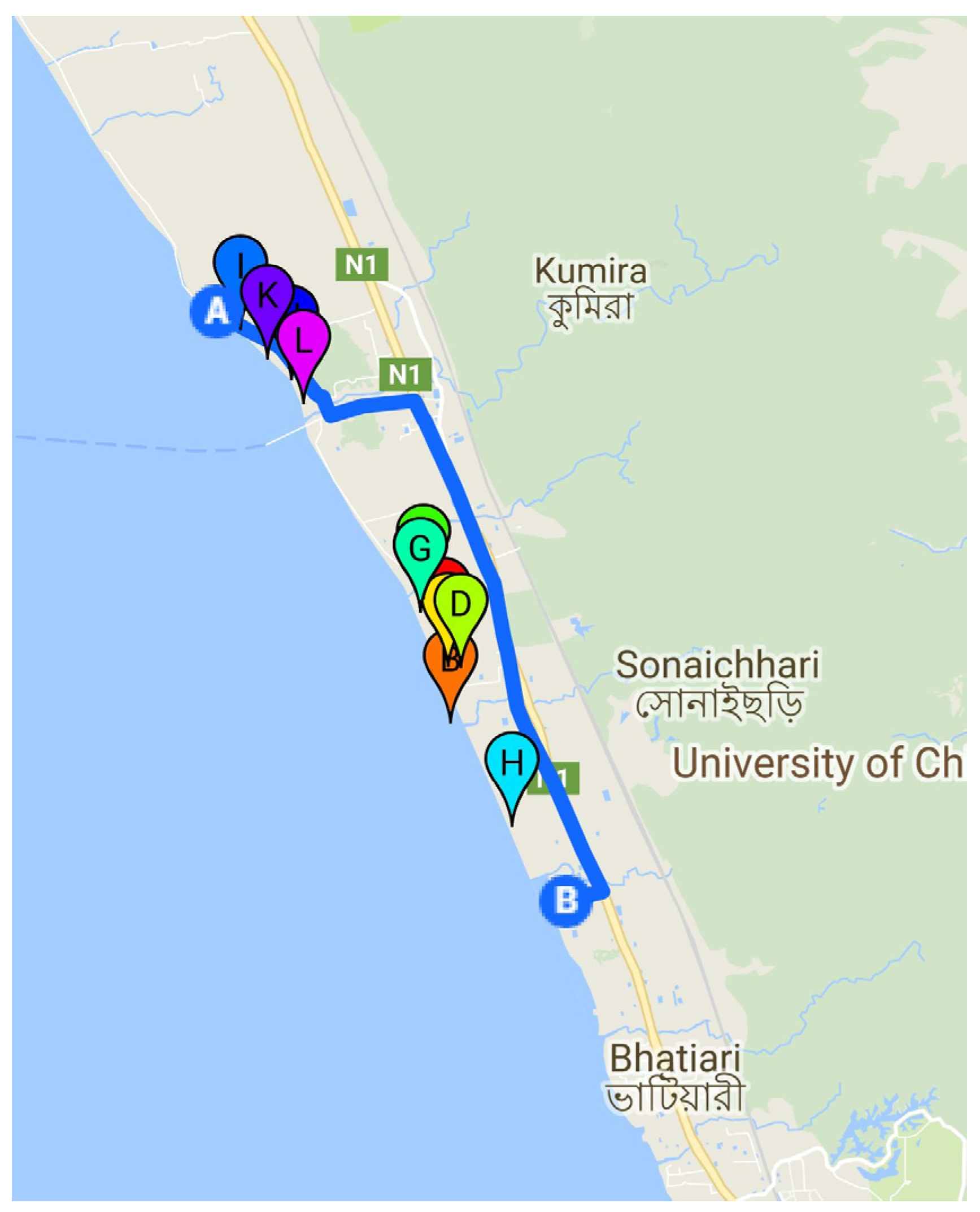

2. Discourse, Framing and Politics of Scale

3. Study Area

Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Environmental Pollution: Inclusion and Exclusion Politics

4.2. Worker Safety Issues: Frames and Counter Frames

The ways the workers are treated in the yard are not humane. They [the yard owners] do not consider them as human. They are abusing these people as they do not get work. Does that mean that we will allow them to die? How can a man remain indifferent to the high number of casualties? It is their mentality that is rotten. They [yard owners] are no longer human; they hunger after money. They profit from the savings that they have to spend for workers training, medical treatment and others. Day by day the accidents are increasing and so are the deaths. We have our documents, please take them; we have documented all workers who died of accidents. Of course the available information we have, we do not have the lists of all casualties, and the actual number is even higher.

Most of the local reporters are not well educated and… they work unpaid. They bully us whenever there is an accident, they demand money from us, even the local police demand money from us. If we do not give money, they inflate the news… Look at these workers are working. What risk do you find in there? Okay, we have accidents, but tell me where is accident free. Please go the police station… and ask the report of people killed in road accidents every day. I am sure the casualties are a hundred times more than us. Why do they report on accidents, why do they not report on employment? How many people do we employ, where do you get the steel made from these scraps?

4.3. Scale Configuration of Actors

4.4. Workers’ Position

5. Discussion

5.1. Theoretical Connections for Workers’ Positions: Worker Interest and Risk Preferences

5.2. Discursive Framing

5.3. Scale Politics and Risk Framing

5.4. Policy Implications

5.5. Implications of Scale Distortion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abdullah, Hasan Muhammad, M. Golam Mahboob, Mehmuna R. Banu, and Dursun Zafer Seker. 2013. Monitoring the Drastic Growth of Shipbreaking Yards in Sitakunda: A Threat to the Coastal Environment of Bangladesh. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 185: 3839–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adger, W. Neil, Tor A. Benjaminsen, Katrina Brown, and Hanne Svarstad. 2001. Advancing a Political Ecology of Global Environmental Discourses. Development and Change 32: 681–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, Aage Bjørn. 2001. Worker Safety in the Ship-Breaking Industries. An Issues Paper. Geneva: The International Labour Office. [Google Scholar]

- Andsager, Julie L. 2000. How Interest Groups Attempt to Shape Public Opinion with Competing News Frames. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 77: 577–92. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, Paul J. 2000. Is There a Decent Way to Break up Ships? ILO Discussion Paper. Geneva: ILO. [Google Scholar]

- Benford, Robert D. 1993. You could be the hundredth monkey. The Sociological Quarterly 34: 195–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bickerstaff, Karen, and Julian Agyeman. 2000. Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment. Annual Review of Sociology 26: 611–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bickerstaff, Karen, and Julian Agyeman. 2009. Assembling Justice Spaces: The Scalar Politics of Environmental Justice in North-east England. Antipode 41: 781–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J. Christopher, and Mark Purcell. 2005. There’s nothing inherent about scale: Political ecology, the local trap, and the politics of development in the Brazilian Amazon. Geoforum 36: 607–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buerk, Roland. 2006. Breaking Ships: How Supertankers and Cargo Ships are Dismantled on the Beaches of Bangladesh. Los Angeles: Chamberlain Brothers. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns, George. 2007. Postcard from Chittagong: Wish You were Here? Critical Perspectives on International Business 3: 266–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, George. 2014. A critical scenario analysis of end-of-life ship disposal: The “bottom of the pyramid” as opportunity and graveyard. Critical Perspectives on International Business 10: 172–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, Kathy, and Linda Liska Belgrave. 2007. Grounded Theory. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Cox, Kevin R. 1998. Spaces of Dependence, Spaces of Engagement and the Politics of Scale, or: Looking for Local Politics. Political Geography 17: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crang, Mike. 2010. The Death of Great Ships: Photography, Politics, and Waste in the Global Imaginary. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 42: 1084–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crotty, Michael. 1998. The Foundations of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research Process. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Demaria, Federico. 2010. Shipbreaking at Alang–Sosiya (India): An Ecological Distribution Conflict. Ecological Economics 70: 250–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devault, Damien A., Briac Beilvert, and Peter Winterton. 2017. Ship breaking or scuttling? A review of environmental, economic and forensic issues for decision support. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 24: 25741–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dey, Arun Bikash. 2016. Life at Death Yard. Available online: http://www.thedailystar.net/frontpage/life-death-yard-202612 (accessed on 26 July 2017).

- Douglas, Mary, and Aaron Wildavsky. 1983. Risk and Culture: An Essay on the Selection of Technological and Environmental Dangers. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Doulton, Hugh, and Katrina Brown. 2009. Ten years to prevent catastrophe? Discourses of climate change and international development in the UK press. Global Environmental Change 19: 191–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar, Arturo. 1998. Whose knowledge, whose nature? Biodiversity, conservation, and the political ecology of social movements. Journal of Political Ecology 5: 53–82. [Google Scholar]

- Escobar, Arturo. 2011. Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ferree, Myra Marx. 2002. Shaping Abortion Discourse: Democracy and the Public Sphere in Germany and the United States. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fiss, Peer C., and Paul M. Hirsch. 2005. The Discourse of Globalization: Framing and Sensemaking of an Emerging Concept. American Sociological Review 70: 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucault, Michel. 1980. Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972–1977. New York: Pantheon. [Google Scholar]

- Freudenburg, William R. 1993. Risk and recreancy: Weber, the division of labor, and the rationality of risk perceptions. Social Forces 71: 909–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, R. Scott. 2015. Breaking Ships in the World-System: An Analysis of Two Ship Breaking Capitals, Alang-Sosiya, India and Chittagong, Bangladesh. Journal of World-Systems Research 21: 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, Julien-François. 2011. Conflicts over industrial tree plantations in the South: Who, how and why? Global Environmental Change 21: 165–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregson, Nicky. 2011. Performativity, Corporeality and the Politics of Ship Disposal. Journal of Cultural Economy 4: 137–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gregson, N., and M. Crang. 2010. Materiality and Waste: Inorganic Vitality in a Networked World. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 42: 1026–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gregson, Nicky, Mike Crang, Farid Ahamed, Nargis Akhter, and Raihana Ferdous. 2010. Following Things of Rubbish Value: End-of-life Ships, ‘Chock-Chocky’ Furniture and the Bangladeshi Middle Class Consumer. Geoforum 41: 846–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gregson, Nicky, Mike Crang, Farid Uddin Ahamed, Nasreen Akter, Raihana Ferdous, Sadat Foisal, and Ray Hudson. 2012. Territorial Agglomeration and Industrial Symbiosis: Sitakunda-Bhatiary, Bangladesh, as a Secondary Processing Complex. Economic Geography 8: 37–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannigan, John. 2006. Environmental Sociology, 2nd ed. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Leila M., and Samer Alatout. 2010. Negotiating hydro-scales, forging states: Comparison of the upper Tigris/Euphrates and Jordan River Basins. Political Geography 29: 148–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, Jean. 2009. Assemblages of justice: The ‘ghost ships’ of Graythorp. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 33: 640–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, Maruf Md M., and Mohammad Mahmudul Islam. 2006. Ship Breaking Activities and Its Impact on the Coastal Zone of Chittagong, Bangladesh: Towards Sustainable Management. Chittagong: Advocacy & Publication Unit, Young Power in Social Action (YPSA). [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M. Shahadat, Sayedur R. Chowdhury, S. M. Abdul Jabbar, S. M. Saifullah, and M. Ataur Rahman. 2008. Occupational Health Hazards of Ship Scrapping Workers at Chittagong Coastal Zone, Bangladesh. Chiang Mai Journal of Science 35: 370–81. [Google Scholar]

- International Maritime Organization. 2016. Evaluation of Environmental Impacts of Ship Recycling in Bangladesh Final Report. Programme No. TC/1514 “SENSREC” Safe and Environmentally Sound Ship Recycling in Bangladesh—Phase I. December. Available online: http://www.imo.org/en/OurWork/Environment/SupportToMemberStates/MajorProjects/Documents/Ship%20recycling/WP1b%20Environmental%20Impact%20Study.pdf (accessed on 13 July 2017).

- Jäger, Seigfried. 2001. Discourse and knowledge: Theoretical and methodological aspects of a critical discourse and dispositive analysis. Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis 1: 32–63. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, Robert, and Elena Nikiforova. 2008. The performativity of scale: The social construction of scale effects in Narva, Estonia. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 26: 537–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kibria, Golam, Md Maruf Hossain, Debbrota Mallick, T. C. Lau, and Rudolf Wu. 2016. Monitoring of metal pollution in waterways across Bangladesh and ecological and public health implications of pollution. Chemosphere 165: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurtz, Hilda E. 2003. Scale frames and counter-scale frames: Constructing the problem of environmental injustice. Political Geography 22: 887–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, Melissa, and Robin Mearns. 1996. The Lie of the Land: Challenging Received Wisdom on the African Environment. London: James Currey Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Lebel, Louis, Po Garden, and Masao Imamura. 2005. The politics of scale, position, and place in the governance of water resources in the Mekong region. Ecology and Society 10: 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litfin, Karen. 1994. Ozone Discourses: Science and Politics in Global Environmental Cooperation. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marston, Sallie A. 2000. The social construction of scale. Progress in Human Geography 24: 219–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, Timothy. 1991. Colonising Egypt. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Norman, Emma, Karen Bakker, and Christina Cook. 2012. Introduction to the themed section: Water governance and the politics of scale. Water Alternatives 5: 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Peet, Richard, and Michael Watts, eds. 1996. Liberation Ecologies: Environment, Development, Social Movements. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Peluso, Nancy Lee, Craig R. Humphrey, and Louise P. Fortmann. 1994. The rock, the beach, and the tidal pool: People and poverty in natural resource-dependent areas. Society & Natural Resources 7: 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Rafey, William, and Benjamin K. Sovacool. 2011. Competing discourses of energy development: The implications of the Medupi coal-fired power plant in South Africa. Global Environmental Change 21: 1141–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S. M. Mizanur, and Audrey L. Mayer. 2015. How Social Ties Influence Metal Resource Flows in the Bangladesh Ship Recycling Industry. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 104: 254–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S. M. Mizanur, and Audrey L. Mayer. 2016. Policy compliance recommendations for international shipbreaking treaties for Bangladesh. Marine Policy 73: 122–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S. M. Mizanur, Robert M. Handler, and Audrey L. Mayer. 2016. Life cycle assessment of steel in the ship recycling industry in Bangladesh. Journal of Cleaner Production 135: 963–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, Carl. 2016. Democratic business ethics: Volkswagen’s emissions scandal and the disruption of corporate sovereignty. Organization Studies 37: 1501–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, Jane, and Liz Spencer. 2002. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. The Qualitative Researcher’s Companion 573: 305–29. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, Paul. 2011. Political Ecology: A Critical Introduction. New York: John Wiley & Sons, vol. 16. [Google Scholar]

- RT Documentary. 2017. Scrapped: Shipbreaking Cutters. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_fqrRhqv0Iw (accessed on 13 July 2017).

- Said, Edward. 1979. Orientalism. New York: Vintage. [Google Scholar]

- Saraf, M., F. Stuer-Lauridsen, M. Dyoulgerov, R. Bloch, S. Wingfield, and R. Watkinson. 2010. The Shipbreaking and Recycling Industry in Bangladesh and Pakistan. Washington: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Sharifuzzaman, S. M., Hafizur Rahman, S. M. Ashekuzzaman, Mohammad Mahmudul Islam, Sayedur Rahman Chowdhury, and M. Shahadat Hossain. 2016. Heavy Metals Accumulation in Coastal Sediments. In Environmental Remediation Technologies for Metal-Contaminated Soils. Tokyo: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiquee, Noman Ahmad, Selina Parween, M. M. A. Quddus, and Prabal Barua. 2012. Heavy Metal Pollution in Sediments at Shipbreaking Area of Bangladesh. In Coastal Environments: Focus on Asian Regions. Edited by V. Subramanian. New Delhi: Capital Publishing Company, pp. 78–87. [Google Scholar]

- Snow, David A., and Robert D. Benford. 1988. Ideology, Frame Resonance, and Participant Mobilization. International Social Movement Research 1: 197–217. [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, Anselm, and Juliet M. Corbin. 1997. Grounded Theory in Practice. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Sujauddin, Mohammad, Ryu Koide, Takahiro Komatsu, Mohammad Mosharraf Hossain, Chiharu Tokoro, and Shinsuke Murakami. 2014. Characterization of shipbreaking industry in Bangladesh. Journal of Material Cycles and Waste Management 17: 72–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swyngedouw, Erik. 2000. Authoritarian governance, power, and the politics of rescaling. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 18: 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swyngedouw, Erik, and Nikolas C. Heynen. 2003. Urban political ecology, justice and the politics of scale. Antipode 35: 898–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Daily Star. 2014. Two Illegal Ship-Breaking Yards Evicted after Five Years. Available online: http://www.shipbreakingbd.info/Two-illegal-ship-breaking-yards-evicted-after-five-years.html (accessed on 26 July 2017).

- Transparency International. 2017. Corruption Perceptions Index 2016. Available online: https://www.transparency.org/news/feature/corruption_perceptions_index_2016 (accessed on 26 July 2017).

- Wiktorowicz, Q. 2004. Islamic Activism: A Social Movement Theory Approach. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- YPSA. 2017. Youth Power in Social Action. Available online: http://ypsa.org/research-and-survey-reports/ (accessed on 26 July 2017).

| Actors | No. of Interviews | Summary of Interviews |

|---|---|---|

| NGOs (YPSA and BELA) | 3 | Yards did not improve and continue to pose a danger to workers and the environment |

| Yard owners/officials | 4 | Yards have improved and the accidents are insignificant compared to other industries. |

| Workers | 13 | Workers are both happy to work and realize the work is risky. They want this industry and do not want it to stop. |

| GOs (DOE, Ministry of Industry) | 5 | The industry is much improved but needs international investment to enhance capacity building. |

| Professors | 4 | There is a need to assess the sources of contamination; need proper data to explore the issues. |

| Local People (living near yards) | 10 | Local people do not blame this industry for either environmental contamination or risks to workers; as they blame the other chemical industries in the area and; instead they view this industry as a job opportunity. |

| Total n = 39 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rahman, S.M.M.; Schelly, C.; Mayer, A.L.; Norman, E.S. Uncovering Discursive Framings of the Bangladesh Shipbreaking Industry. Soc. Sci. 2018, 7, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7010014

Rahman SMM, Schelly C, Mayer AL, Norman ES. Uncovering Discursive Framings of the Bangladesh Shipbreaking Industry. Social Sciences. 2018; 7(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleRahman, S. M. Mizanur, Chelsea Schelly, Audrey L. Mayer, and Emma S. Norman. 2018. "Uncovering Discursive Framings of the Bangladesh Shipbreaking Industry" Social Sciences 7, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci7010014