What Is Behind? Impact of Pelvic Pain on Perceived Stress and Inflammatory Markers in Women with Deep Endometriosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Data Collection Procedures

2.3. Pain

2.4. Stress Markers

2.5. Inflammatory Markers

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fedele, F.; Di Fatta, S.; Busnelli, A.; Bulfoni, A.; Salvatore, S.; Candiani, M. Rare extragenital endometriosis: Pathogenesis and therapy. Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 49, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koninckx, P.R.; Ussia, A.; Adamyan, L.; Tahlak, M.; Keckstein, J.; Wattiez, A.; Martin, D.C. The epidemiology of endometriosis is poorly known as the pathophysiology and diagnosis are unclear. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2021, 71, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehedintu, C.; Plotogea, M.; Ionescu, S.; Antonovici, M. Endometriosis still a challenge. J. Med. Life 2014, 7, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Parazzini, F.; Esposito, G.; Tozzi, L.; Noli, S.; Bianchi, S. Epidemiology of endometriosis and its comorbidities. Eur. J. Obstetrics Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2017, 209, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allaire, C.; Bedaiwy, M.A.; Yong, P.J. Diagnosis and management of endometriosis. CMAJ Can. Med. Assoc. J. J. De L’association Medicale Can. 2023, 195, E363–E371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clower, L.; Fleshman, T.; Geldenhuys, W.J.; Santanam, N. Targeting Oxidative Stress Involved in Endometriosis and Its Pain. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, D.; Pathak, G.A.; Wendt, F.R.; Tylee, D.S.; Levey, D.F.; Overstreet, C.; Gelernter, J.; Taylor, H.S.; Polimanti, R. Epidemiologic and Genetic Associations of Endometriosis With Depression, Anxiety, and Eating Disorders. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2251214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simoens, S.; Dunselman, G.; Dirksen, C.; Hummelshoj, L.; Bokor, A.; Brandes, I.; Brodszky, V.; Canis, M.; Colombo, G.L.; DeLeire, T.; et al. The burden of endometriosis: Costs and quality of life of women with endometriosis and treated in referral centres. Hum. Reprod. 2012, 27, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamceva, J.; Uljanovs, R.; Strumfa, I. The Main Theories on the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, A.; Moar, K.T.K.A.; Maurya, P.K. Biomarkers of endometriosis. Clin. Chim. Acta 2023, 549, 117563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gruber, T.M.; Mechsner, S. Pathogenesis of Endometriosis: The Origin of Pain and Subfertility. Cells 2021, 10, 1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachedina, A.; Todd, N. Dysmenorrhea, Endometriosis and Chronic Pelvic Pain in Adolescents. J. Clin. Res. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 2020, 12 (Suppl. S1), 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amini, L.; Chekini, R.; Nateghi, M.R.; Haghani, H.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sathyapalan, T.; Sahebkar, A. The Effect of Combined Vitamin C and Vitamin E Supplementation on Oxidative Stress Markers in Women with Endometriosis: A Randomized, Triple-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial. Pain Res. Manag. 2021, 2021, 5529741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmioglu, N.; Mortlock, S.; Ghiasi, M.; Møller, P.L.; Stefansdottir, L.; Galarneau, G.; Turman, C.; Danning, R.; Law, M.H.; Sapkota, Y.; et al. The genetic basis of endometriosis and comorbidity with other pain and inflammatory conditions. Nat. Genet. 2023, 55, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Aken, M.; Oosterman, J.; van Rijn, T.; Ferdek, M.; Ruigt, G.; Kozicz, T.; Braat, D.; Peeters, A.; Nap, A. Hair cortisol and the relationship with chronic pain and quality of life in endometriosis patients. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018, 89, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulletti, C.; Coccia, M.E.; Battistoni, S.; Borini, A. Endometriosis and infertility. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2010, 27, 441–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiarotto, A.; Maxwell, L.J.; Ostelo, R.W.; Boers, M.; Tugwell, P.; Terwee, C.B. Measurement Properties of Visual Analogue Scale, Numeric Rating Scale, and Pain Severity Subscale of the Brief Pain Inventory in Patients With Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review. J. Pain 2019, 20, 245–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de França Moreira, M.; Gamboa, O.L.; Pinho Oliveira, M.A. Association between severity of pain, perceived stress and vagally-mediated heart rate variability in women with endometriosis. Women Health 2021, 61, 937–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawker, G.A.; Mian, S.; Kendzerska, T.; French, M. Measures of adult pain: Visual Analog Scale for Pain (VAS Pain), Numeric Rating Scale for Pain (NRS Pain), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Chronic Pain Grade Scale (CPGS), Short Form-36 Bodily Pain Scale (SF-36 BPS), and Measure of Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain (ICOAP). Arthr. Care Res. 2011, 63 (Suppl. S11), S240–S252. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, M.d.F.; Gamboa, O.L.; Oliveira, M.A.P. Mindfulness intervention effect on endometriosis-related pain dimensions and its mediator role on stress and vitality: A path analysis approach. Arch. Women’s Ment. Health 2024, 27, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dworkin, R.H.; Turk, D.C.; Peirce-Sandner, S.; Burke, L.B.; Farrar, J.T.; Gilron, I.; Jensen, M.P.; Katz, N.P.; Raja, S.N.; Rappaport, B.A.; et al. Considerations for improving assay sensitivity in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain 2012, 153, 1148–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yılmaz Koğar, E.; Koğar, H. A systematic review and meta-analytic confirmatory factor analysis of the perceived stress scale (PSS-10 and PSS-14). Stress Health J. Int. Soc. Investig. Stress 2023, 40, e3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, J.; Gu, L.; Chen, Y.; Liu, X.; Yang, J.; Li, M.; Dong, X.; Yang, S.; Huang, B.; Wang, T.; et al. Evaluation of psychological stress, cortisol awakening response, and heart rate variability in patients with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome complicated by lower urinary tract symptoms and erectile dysfunction. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 903250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eller-Smith, O.C.; Nicol, A.L.; Christianson, J.A. Potential Mechanisms Underlying Centralized Pain and Emerging Therapeutic Interventions. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrelluzzi, K.F.S.; Garcia, M.C.; Petta, C.A.; Ribeiro, D.A.; Monteiro, N.R.d.O.; Céspedes, I.C.; Spadari, R.C. Physical therapy and psychological intervention normalize cortisol levels and improve vitality in women with endometriosis. J. Psychosom. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 33, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thüroff, J.W.; Casper, F.; Heidler, H. Pelvic floor stress response: Reflex contraction with pressure transmission to the urethra. Urol. Int. 1987, 42, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heim, C.; Ehlert, U.; Hanker, J.P.; Hellhammer, D.H. Abuse-related posttraumatic stress disorder and alterations of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in women with chronic pelvic pain. Psychosom. Med. 1998, 60, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrelluzzi, K.F.S.; Garcia, M.C.; Petta, C.A.; Grassi-Kassisse, D.M.; Spadari-Bratfisch, R.C. Salivary cortisol concentrations, stress and quality of life in women with endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain. Stress 2008, 11, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, R.U.; Orenberg, E.K.; Morey, A.; Chavez, N.; Chan, C.A. Stress induced hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis responses and disturbances in psychological profiles in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J. Urol. 2009, 182, 2319–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schrepf, A.; O’Donnell, M.A.; Luo, Y.; Bradley, C.S.; Kreder, K.J.; Lutgendorf, S.K. Inflammation and Symptom Change in Interstitial Cystitis or Bladder Pain Syndrome: A Multidisciplinary Approach to the Study of Chronic Pelvic Pain Research Network Study. Urology 2016, 90, 56–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, M.A.; Wand, G. Stress and the HPA axis: Role of glucocorticoids in alcohol dependence. Alcohol Res. Curr. Rev. 2012, 34, 468–483. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 37.81 | 6.9 |

| Height (cm) | 166.84 | 6.04 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.07 | 2.49 |

| Menarche (age) | 11.21 | 0.99 |

| Pain (months) | 16.94 | 8.37 |

| Pelvic pain | 7.19 | 2.86 |

| Lower back pain | 5.87 | 3.40 |

| Dysmenorrhea | 7.81 | 2.87 |

| Dyspareunia | 5.91 | 2.91 |

| Dyschezia | 3.60 | 3.09 |

| Strangury | 2.02 | 2.45 |

| Categorical Variables | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Births | ||

| 0 | 29 | 58% |

| 1 or more | 21 | 42% |

| Cesarean Deliveries | ||

| 0 | 27 | 53% |

| 1 | 24 | 29% |

| 2 | 9 | 18% |

| Abortions | ||

| 0 | 40 | 82% |

| 1 or 2 | 9 | 18% |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 36 | 75% |

| Latin/Black | 12 | 25% |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 40 | 80% |

| Single | 10 | 20% |

| PSS Score | ||

| Low stress (≤26) | 29 | 56% |

| High stress (>26) | 23 | 44% |

| Pain Symptoms | Low | NRS | High | NRS | p | ES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stress (n) | (Mean; SD) | Stress (n) | (Mean; SD) | |||

| Dysmenorrhea | 21 | 6.7; 3.3 | 15 | 9.2; 1.5 | 0.017 | 0.85 |

| Dyspareunia | 24 | 4.96; 3.10 | 19 | 7.11; 2.18 | 0.014 | 0.78 |

| Strangury | 29 | 1.07; 1.89 | 23 | 3.22; 2.58 | 0.001 | 0.97 |

| Dyschezia | 29 | 1.93; 2.64 | 23 | 5.70; 2.22 | <0.001 | 1.52 |

| Lower Back Pain | 29 | 4.38; 3.23 | 23 | 7.74; 2.61 | <0.001 | 1.13 |

| Pelvic Pain | 29 | 6.14; 3.14 | 23 | 8.52; 1.78 | 0.002 | 0.91 |

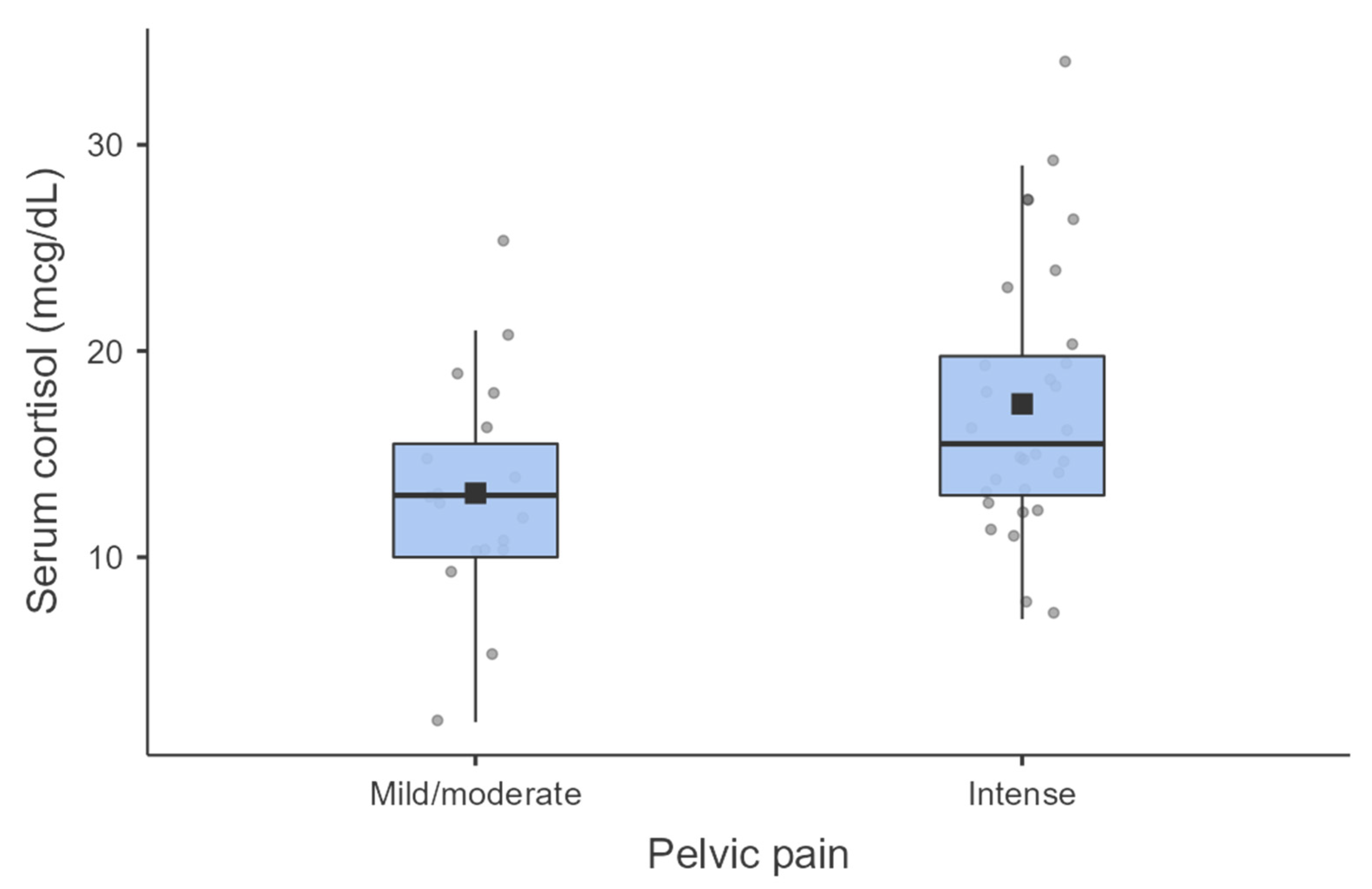

| Variables | Mild/Moderate Pain (n) | NRS (Mean; SD) | Severe Pain (n) | NRS (Mean; SD) | p | ES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum Cortisol | 19 | 13.11; 5.35 | 30 | 17.43; 6.44 | 0.018 | 0.72 |

| CRP | 21 | 9.52; 15.86 | 30 | 10.73; 29.72 | 0.866 | 0.05 |

| ESR | 20 | 3.75; 4.47 | 30 | 7.07; 15.71 | 0.364 | 0.26 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Osaki, J.D.; Oliveira, M.A.P. What Is Behind? Impact of Pelvic Pain on Perceived Stress and Inflammatory Markers in Women with Deep Endometriosis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2927. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13102927

Osaki JD, Oliveira MAP. What Is Behind? Impact of Pelvic Pain on Perceived Stress and Inflammatory Markers in Women with Deep Endometriosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024; 13(10):2927. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13102927

Chicago/Turabian StyleOsaki, Jordana Diniz, and Marco Aurelio Pinho Oliveira. 2024. "What Is Behind? Impact of Pelvic Pain on Perceived Stress and Inflammatory Markers in Women with Deep Endometriosis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 13, no. 10: 2927. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13102927

APA StyleOsaki, J. D., & Oliveira, M. A. P. (2024). What Is Behind? Impact of Pelvic Pain on Perceived Stress and Inflammatory Markers in Women with Deep Endometriosis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 13(10), 2927. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm13102927