Abstract

In emerging countries like Romania, research on food loss and waste remains relatively scarce. This is mainly because the phenomenon, along with its repercussions and ramifications, is inadequately understood by all stakeholders within the agri-food chain. Consumer behaviour, with a specific focus on sustainability and waste reduction, has undergone a noticeable transformation on a global scale. Researchers have been emphasising the imperative for effective awareness and education strategies in this respect. Diverse studies contribute valuable insights into household food behaviour, identifying possible drivers and suggesting counteractive techniques. This study poses inquiries about consumer feelings regarding the food waste phenomenon and perceptions of the Romanian agri-food chain, as well as the influence of education on their awareness and adoption of sustainable eating habits. The paper delineates the semi-structured interview-based methodology, shows results through word-cloud and sentiment analysis, and engages in discussions on consumer behaviour through four distinct clusters, concluding with limitations, managerial implications and outlining future research directions. The findings underscore the relevance of emotions and sentiments in understanding consumer behaviour, shedding light on the nuanced factors influencing food waste. Notably, the accuracy of interpretation is higher when drawn from interviews rather than online comments or reviews made by unknown individuals. This distinction increases the credibility of the insights gained from the qualitative study. By analysing consumer sentiments, the study aids in implementing strategies to improve customer satisfaction and reduce food waste, fostering a more sustainable and consumer-centric approach in the agri-food sector worldwide.

1. Introduction

In the current international context, the food loss and waste issue has become increasingly researched due to several factors such as a growing awareness of environmental issues, a shift in attitudes towards sustainable production and consumption systems, the advancement of technological solutions, the pandemic crisis, and consequent governmental policy interventions. The world landscape prompted visible changes in consumer behaviour, characterised by a focus on sustainability, responsibility, and the adoption of practices for a reduction in waste.

Recent research findings on consumer behaviour related to food waste provide a complex perspective on this global problem. According to Goswami and Chouhan [1], consumer behaviour plays a crucial role in managing food waste, highlighting the need for effective awareness and education strategies. Several factors influence the generation and management of food waste at the household level [2]. This perspective makes significant contributions to understanding local and regional issues and potential solutions for combatting food waste behaviour. In the developing world context, consumer food waste can also be resultant of problems in earlier stages of the food chain (e.g., inadequate pest control, use of inadequate packages to store or transport foods, lack of cold chain). Quested [3] brings into question the complex behaviour of food waste, highlighting connections and patterns that can have significant implications for the adoption of sustainable practices. Research on household food behaviour provides key insights into the development of strategies to combat food waste on a global scale [4,5]. Jones and Wells’ study [6], which focuses on examining food waste in the United States, offers specific insights into the American food system, highlighting the impact of food labelling on waste generation. Additionally, Stancu et al. [7] provide insights into the determinants of consumer behaviour in generating food waste, paving the way for identifying practical solutions to reduce it.

According to other authors [8,9,10], food waste at the consumption stage is a direct outcome of consumer purchasing behaviour, as it is at this stage that buying decisions translate into actual consumption patterns. Numerous researchers have approached the topic of food waste at the household and individual consumer level [11,12,13], analysing the most common types [14,15,16] and causes [17,18,19] of wasted food and the strategies employed to address this phenomenon [20,21]. Moreover, in addition to the preferences, habits, attitudes, and external influences, several determining factors have also been considered: impulsive buying, driven by promotional offers or attractive packaging; lack of education and awareness regarding the consequences of food waste and loss phenomenon; and cultural and social norms [22,23,24].

Most research in this area relies on a predominantly quantitative approach [13,25,26] based on surveys, while qualitative studies are less common [20,27] with none of them incorporating the sentiment analysis.

Therefore, this investigation seeks to address this research gap by using a qualitative methodology, in the context of an emerging market. Consumer-based data were analysed with the help of R software version 4.2.1., employing word cloud and sentiment analysis.

Furthermore, this research explores the diversity of consumer behaviour towards the phenomenon of food waste in Romania and to identify prevalent themes, key sentiments, emotions, and associations surrounding food loss and waste. Despite increasing global awareness of the environmental and economic impacts of food waste, Romania still discards significant amounts of food (2.2 Mn tons annually) [28]. Romania officially embraced 29 September as the International Awareness Day for Combatting Food Waste, aligning not only with other nations and the United Nations General Assembly’s resolution (MADR) but also with law no. 217/2016 regarding the reduction in food waste and the European Parliament Resolution of 19 January 2012, concerning the avoidance of food waste and strategies to enhance the efficiency of the EU food chain (MADR). This persistent issue is not only a matter of sustainability but also has broader implications for resource management, economic efficiency, and social responsibility.

Therefore, the research objectives of this study are multifaceted, including a comprehensive exploration of consumer behaviour in the context of food waste. The primary objective is to underscore the major role played by emotions and sentiments in shaping consumer decisions related to food (purchase and consumption). A key aspect involves a detailed analysis of nuanced factors contributing to food waste, with a focus on the complexities inherent in consumer behaviour. Additionally, this study aims to evaluate the accuracy of interpretation derived from interviews, emphasising the reliability of insights obtained through qualitative methods. Lastly, the research analyses consumer sentiments to help stakeholders formulate and implement effective strategies for a sustainable and consumer-centric approach within the global agri-food sector. Conducting a survey with all agri-food chain stakeholders allowed researchers to raise awareness among stakeholders of the agri-food chain. The data provided by the answers helped identify key issues and challenges (such as environmental concerns or supply chain inefficiencies). Additionally, a comprehensive understanding of the stakeholders’ perspectives (from farmers to consumers) was provided, and every respondent’s feedback gave valuable insights for future strategies of improvement, whether it involves implementing eco-friendly farming practices, optimising distribution channels, or changing consumer behaviours in the best possible way. Thus, the research objective to foster dialogue and support future common strategies for a more sustainable food industry was met.

The research deepens the understanding of consumers food waste and loss behaviour in an emerging market, providing valuable insights for the development of targeted interventions and strategies to mitigate or diminish food waste. From a policy perspective, it is necessary that local and/or central governmental authorities are informed about this phenomenon, so that they properly understand the complexity of the topic and identify early strategies to solve this issue. By leveraging insights gained from such analysis, stakeholders can effectively tackle food waste issues and promote more sustainable practices throughout the agri-food sector in Romania.

Although this kind of approach (word cloud and sentiment analysis) dealing with food consumer behaviour is a relatively niche area, there are a few studies and research articles in the literature which touch upon related topics such as consumer food preferences [29] attitudes, experiences [30], and behaviours in the food industry [31]. Moreover, the study of Russell et al. [32] brings into question the influence of emotions and habits in food waste conduct, highlighting the importance of addressing individuals’ feelings with relation to food. Other authors explored social media posts related to food waste to identify priorities for campaigns [33].

The identified studies use word cloud and sentiment analysis, but they do not address specific aspects of consumer behaviour related to food waste. Therefore, the authors of the present research filled this identified gap relying on a sentiment analysis study on food waste consumer behaviour in Romania.

The paper addressed the following research question:

RQ: How do various perceptions of consumers regarding the agri-food chain reflect the diversity of their behaviour related to food waste?

By promoting responsible purchasing, local products, and healthy practices in the agri-food chain, consumer behaviour towards food waste can be influenced, which contributes to reducing its environmental impact, fostering a culture of mindful consumption and educating younger generations. Furthermore, the involvement of companies and NGOs is crucial for implementing sustainable initiatives and creating systemic changes that pave the way for a more sustainable future. Collectively, with shared efforts and commitment, progress can be made towards a future where food waste is minimised, and resources are used efficiently.

The paper is structured as follows: Section 2 presents the methodology. This is followed by the results in Section 3, which consists of two sub-sections: the word cloud and sentiment analysis (Section 3.1) and the cluster analysis (Section 3.2). The paper then proceeds with Section 4. Finally, Section 5 ends the paper with managerial implications, study limitations, and directions for future research.

2. Methodology

This qualitative research is grounded in data collected through a semi-structured interview guide, which allows an in-depth exploration of key themes and topics [34]. The primary focus areas of the research instrument included the following: consumer behaviour associated with food waste; perceptions of the agri-food chain among consumers; consumer perspectives on stakeholders’ strategies for addressing food waste in the agri-food sector; understanding of food loss and waste; and consumer education initiatives aimed at reducing food waste. A total of 104 semi-structured interviews were conducted between March and May 2023. Taking into account available resources, including time and budget constraints, it was determined that conducting 104 interviews was feasible and could generate enough information to address the research question effectively. A total of 104 interviews seemed sufficient to reach data saturation, the point where new interviews no longer provided new or significant information. The latter appeared sufficient to address the research question and reach a profound understanding of the topic. Additionally, there was a consistent and regular evaluation of the quality of the collected data to ensure that the content was adequate for the research objectives [35,36].

The participants were randomly selected from several regions of Romania, with different age categories, both male and female, and various activity backgrounds.

The study, based on 104 responses, presents a breakdown of demographics showing that 70.19% (73 responses) were male, with 29.81% (31 responses) being female. Furthermore, most respondents (73.08%, specifically 76 responses), live in urban areas, while 26.92% (28 responses) live in rural households. Regarding the age distribution, it was noticed that 29% of respondents ranged between 20 and 30 years old, and about 25% ranged between 31 and 40 years old. Approximately 27% were aged 41–50 years old and 19% were over 50. Concerning shopping habits, 55.77% of respondents prefer shopping in the evening, followed by 39.42% in the afternoon, and the remaining 4.81% in the morning. In terms of education, 46% of respondents reported having higher education, while the remaining 54% had secondary and high school education levels. Furthermore, the analysis indicates that respondents predominantly possess medium to high incomes, allowing them to afford high-quality products and support local producers.

All participants were chosen based on their sensitivity to the food loss and waste problem. This sampling enabled the exploration of a wide spectrum of opinions and behaviours related to the food waste and loss topic, thereby contributing to a rich and comprehensive understanding of this phenomenon from the consumers’ perspective.

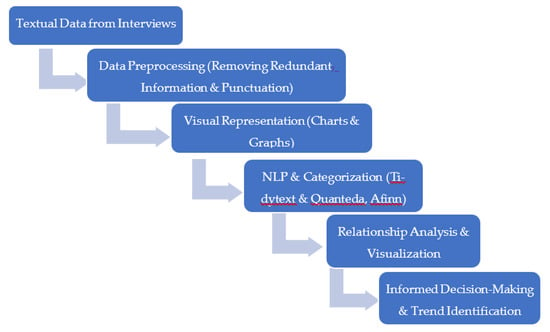

The interviews were transcribed as recommended by the literature [35]. After the data were cleaned and systematised, different analyses were performed with the help of R software, such as the sentiment analysis, which enabled an assessment of consumer attitudes and emotions towards food waste. A cluster analysis was also used, which enabled the identification of four consumer clusters. Therefore, different libraries from R were used, such as Tidytext, Sentimentr, and Quanteda [37] for the foreseen investigation. The applied procedure of data analysis in R (Figure 1), involved several essential steps [36,37,38]: first, the textual data from the interviews were extracted and processed in R version 4.2.1. to remove redundant information and punctuation marks. Then, using charts and graphs from software packages such as ggplot2 and plotly, visual representations of overall trends and patterns in the textual data were obtained. A crucial component of the analysis was the measurement of term dispersion using the unusualness matrix, which provides clues about the variety and uniformity of terms in the text. An association matrix (uncommon matrix [39]) was also formulated to identify terms that co-occur with greater than random frequency [40]. Term co-occurrence measurement and natural language processing (NLP) were performed using the Tidytext and Quanteda packages in R [41,42]. Codes in the text were categorised into relevant themes or topics, and the relationships between them were analysed and visualised using the IGRAPH library in R [43]. These steps led to insights and interpretation of textual data, facilitating informed decision-making, and identifying trends and patterns in the analysed data.

Figure 1.

The steps involved in the analysis.

This methodological approach provided an in-depth understanding of the discursive content and attitudes expressed, underpinning the subsequent qualitative analysis.

The results, presented in the following section, were obtained by applying this methodological approach and have made a significant contribution to understanding the depth of the discursive content and the attitudes expressed by consumers in relation to food waste. Analysis of the terms and their co-occurrence revealed significant patterns and associations, providing clues to consumer priorities in this area. Also, the identification of the four distinct groups of consumers, based on sentiment analysis, allowed a more precise segmentation of the population according to attitudes and emotions related to food waste. Qualitative data were converted into a matrix format, utilising R packages to perform analysis and identify distinct consumer clusters based on responses or characteristics. Furthermore, an interpretation of the four identified clusters was made, followed by a validation (by assessing distinctiveness, to ensure alignment with the consumers’ perspectives and experiences). Through the visualisation of the results, a comprehensive and coherent analysis of the textual data could be achieved, facilitating a deeper understanding of the FLW subject, and supporting the informed decision-making process.

In conclusion, research on sentiment analysis suggests that its accuracy varies widely depending on the method and context [44]. Sentiment analysis has been found to outperform dictionary-based methods like content analysis and to approach human performance when using machine learning algorithms [45], like R, the software which was used to analysis the interview-based qualitative data. Sentiment analysis has been found to be a valuable tool for analysing qualitative data, particularly in the social sciences [46].

3. Results

3.1. A Word Cloud and Sentiment Analysis

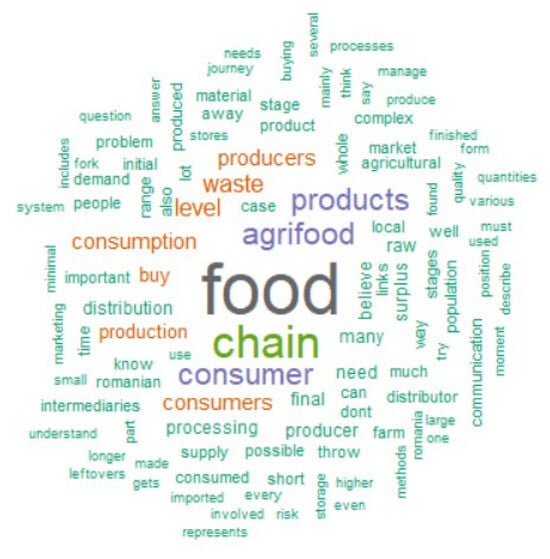

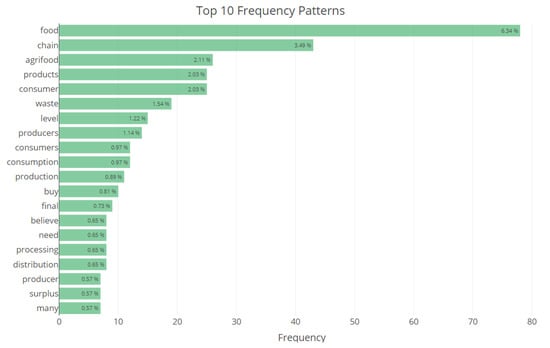

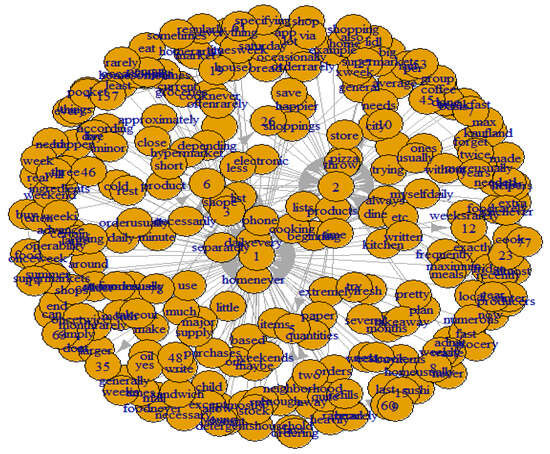

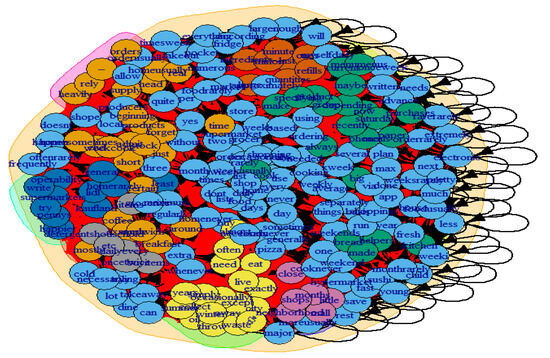

In the analysis of terms relevant to consumer behaviour and the agri-food chain, several key concepts were identified (Figure 2). The frequency of terms provides insight into how respondents described their consumer behaviour and perceived the agri-food chain (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

A word cloud analysis.

Figure 3.

The top 10 most frequent terms.

Within the analysis of terms, the identified key concepts shed light on how interviewed participants describe their consumer behaviour and perceive the agri-food chain. This analytical approach reveals a complex picture of the participants’ perceptions and priorities, disclosing not only concrete aspects of their behaviour but also significant links within the agri-food chain. In analysing word frequency in the dataset relevant to the research, several key statistics that reflect word distribution and variation were identified:

- Min (Minimum): 1000—This value indicates that each word in the dataset occurs at least once, highlighting the lexical diversity present.

- 1st Qu. (Quartile): 1000—Here, 25% of the words have a frequency of at least 1, suggesting significant variety in the vocabulary used in the context.

- Median: 1.000—With a median of 1, this represents the middle value, indicating that half of the words have a frequency of at least 1, highlighting the evenness in the distribution of words.

- Mean: 2.202—The mean word frequency in the dataset shows a more significant variation, suggesting that there are higher frequency words influencing the mean value.

- 3rd Qu. (Quartile): A total of 75% of words have a frequency of at least 2, reflecting an increase in frequency for a significant number of words.

- Max (Maximum): A total of 78—there are words with a significantly higher frequency, suggesting that they might be considered keywords.

Based on participants’ descriptions and perceptions, a noteworthy total of 78 occurrences were garnered, making the term ‘food’ the central point of the analysis. This indicates a strong focus on food in the participants’ discussions and underlines its importance in this study. This result suggests that food behaviour and preferences are key issues in the evaluation of the agri-food chain. The word ‘food’ is followed by ‘chain’ with 43 occurrences revealing the importance of interconnectivity in the agri-food chain. This underlines the recognition of the close links between producers, processors, distributors, and consumers, highlighting that changes in one part can have a significant impact on the whole system.

With 26 occurrences, ‘agrifood’ points out the integrated perspective on the agricultural and food sector. This broad approach reflects an awareness of the close interaction between production and consumption across the entire agri-food chain. The focus on ‘consumer’ (sg) and ‘consumers’ (pl.) (with 25 and 12 occurrences, respectively) indicates the importance of understanding consumers’ needs, behaviours, and perceptions of agri-food products. This detailed analysis can contribute to the development of strategies to meet consumer demands and promote sustainable food choices. The word ‘waste’ with 19 occurrences underlines the concern about the food waste issue. The latter reflects the commitment to identify and implement sustainable practices to reduce food waste in the agri-food chain.

Taken together, these keywords reveal the complexity of the agri-food chain and underline the importance of collaboration between all stakeholders to promote food responsibility. Detailed analysis of these terms provides a solid basis for a deeper understanding of the complex dynamics involved in the relationship between consumers and the agri-food chain, thus helping stakeholders to inform future decisions and techniques of improvement.

By extending this analysis to other terms, the term ‘reduce’ was identified; considering its significant frequency, ‘reduce’ indicates a clear intention to minimise certain aspects of consumer behaviour as well as a deep concern for sustainability and responsibility in the management of food resources, underlining the need for more efficient approaches. The implementation of strategies, aimed at reducing unnecessary consumption or food waste, thus becomes essential for organisations, contributing to a reduction in environmental impacts. Organisations can use this understanding to develop integrated strategies, optimising efficiency and sustainability at each level of the agri-food chain. The term ‘ways (of)’ adds a dimension of diversity and varied approaches to consumption behaviour and chain management.

This diversity can be influenced by factors such as personal preferences, culture, or environment, highlighting the complexity of choices made by consumers and producers. Adapting strategies to respond to this diversity becomes essential, offering products and services tailored to the consumers’ needs and preferences. Another significant aspect is brought by the term ‘point’ which can refer to a specific moment or significant aspect in the context of food consumption. This may represent a moment of decision or a specific food-related concern.

Organisations can identify these critical ‘points’ and develop strategies to address consumer needs and concerns at those key moments. The term ‘customers’ with a frequency index of 2 emphasises the importance of customers in the agri-food chain. This may suggest a focus on the relationship between producers and consumers and the impact of customer decisions on the agri-food chain. The term ‘taken’ may suggest an action or decision taken, but it could refer to actions taken by consumers or producers to manage food in a specific way, possibly indicating proactive initiatives. With a frequency of 2, the word ‘processors’ refers to entities that process food at different stages of the agri-food chain. This term indicates a recognition of the essential role of processors in preparing food for consumption. The term ‘thrown’ indicates the disposal or discarding of food, suggesting waste. It can be associated with consumption practices or losses. Identifying this term can reveal awareness of the problems of waste and the need for effective solutions. The term ‘often’ indicates frequency and can provide information on habits. If associated with actions such as regular shopping or cooking, it can suggest a constant behaviour and can influence the whole chain through constant demand.

Overall, the central term, ‘Food’, with a high frequency of 78, highlights the importance attached to this aspect under discussion. It serves as the focal point of the research, suggesting that participants paid particular attention to food and food products in the context of the study. Another significant term, ‘Chain’, with a frequency of 43, suggests a strong interest in the interconnectedness of the different elements in the agri-food chain. This finding indicates the importance of exploring the relationships and dependencies between producers, processors, distributors, and consumers within the whole system and visible recognition that changes on one side can determine fluctuations on the other. The term ‘agri-food’, with a frequency of 26, emphasises an integrated perspective covering both the agricultural (production) and food (consumption) sectors. The focus on the buyer is highlighted by the term ‘consumer’, with a frequency of 25. ‘Diversity of Products’ reflects, with a frequency of 25, the variety of existing products analysed in the study. This opens opportunities to explore consumer preferences and choices in terms of product categories.

Concern about food waste is highlighted by the term ‘waste’ with a frequency of 19, suggesting that research can address food waste management habits and propose effective solutions in this direction. The term ‘level’ with a frequency of 15 suggests an interest in the different stages of the studied chain, it involves analysis of production, distribution and consumption, highlighting their complexity and interconnectedness. The term ‘producers’, with a frequency of 14, underlines the crucial role of producers in ensuring food supply. Research can explore the challenges and opportunities they face in the agri-food chain. The term ‘consumption’ with a frequency of 12, highlights aspects of food consumption, paving the way for analysis of consumer behaviour and motivations in the choice of products. ‘Consumers’, with a frequency of 12, emphasises the importance of understanding the consumers’ needs and preferences. Aspects such as quality and price can influence their decisions and are interlinked with sustainability. Looking at the outcome of the research on consumer behaviour and the agri-food chain, these analyses and interpretations of key terms can serve as a conceptual background for a deeper understanding of the complex dynamics involved in the relationship between consumers and the agri-food chain. This knowledge could provide the basis for identifying effective food chain and consumer behaviour management strategies that impact on food chain sustainability and human responsibility.

Analysis of relevant terms in the participants’ words provides a comprehensive understanding of their perceptions and priorities. The interviewed people highlighted various aspects of food behaviour, while stressing the importance of certain elements within the agri-food chain. Eating behaviour-related terms suggest various practices. Reduce suggests a strong intention to minimise certain aspects of food behaviour, indicating a concern for sustainability and responsibility in the management of food resources. Participants may be oriented towards practices such as reducing meat consumption, avoiding food waste, and choosing local products. Waste highlights concern about food disposal. Participants can be sensitive to the need to manage food resources efficiently by adopting practices such as recycling, donating unused food and reducing disposable packaging. Consumption indicates a focus on aspects of food use, paving the way for analysis of motivations in the choice of agri-food products.

Quality and price can be key factors in consumption decisions. Product diversity (Products) reflects the variety of foodstuffs analysed in the study. This opens up opportunities for exploring consumer preferences and choices in terms of product categories. Participants may be interested in food diversity and food alternatives, respectively. All agri-food chain related-terms were also interpreted. Chains is a term which highlights the existence of significant links between the agri-food stakeholders. This highlights participants’ perception of the interdependence of the different stages of the chain and their recognition that changes in one part can affect the whole system. ‘Producers’ is a word which emphasises the crucial role of suppliers. Participants can recognise the challenges and opportunities faced by producers in the agri-food chain.

The general feeling from the analysis carried out using the Tidytext package is one of reflection on the consumers’ evolving behaviours and mindsets. This analysis explored keywords associated with fields such as consumer behaviour, the agri-food chain, shopping, food ordering and home cooking. In terms of consumption and purchasing behaviour, terms such as ‘mostly’, ‘much’, ‘never’, and ‘occasionally’ are evaluated neutrally, reflecting quantitative aspects without adding a strong emotional connotation. This analysis brings out a balanced perspective on consumption habits. As far as the agri-food chain is concerned, terms such as ‘waste’ and ‘shopping habits’ are treated neutrally, except for ‘waste’ which carries a negative connotation, indicating a concern for the efficient management of food resources. Food ordering and home cooking are addressed in an objective and balanced manner, according to the results of the analysis. Terms such as ‘order’ ‘ordering’ ‘cook’ and ‘cooking’ are perceived in a neutral way, suggesting a pragmatic approach to these activities. The analysis indicates an overall neutral and informative attitude in the analysed discussions. Apart from food waste, which is associated with a negative feeling, the other topics are approached objectively, without conveying strong emotions or value judgments.

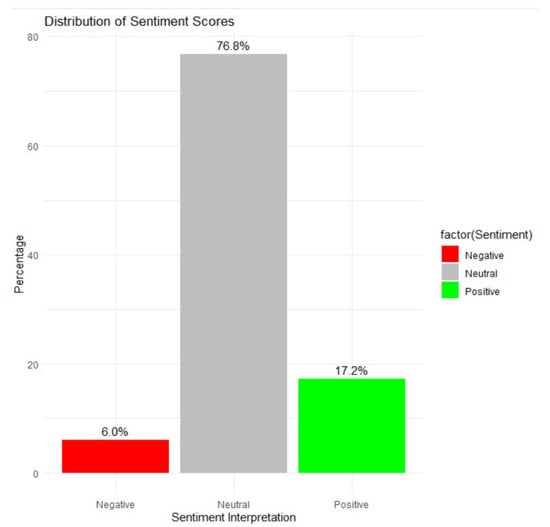

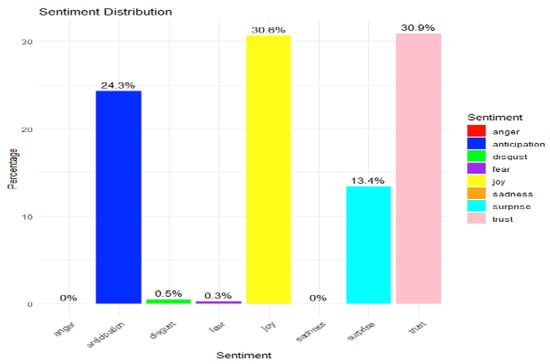

The application of corpus-based sentiment analysis revealed specific consumer behaviours in the agri-food chain (Figure 4). Sentiment scores ranged from −1.000 to −0.250, with a mean of −0.572. This indicates the presence of predominantly negative feelings and personal emotions (Min. = −1.000, 1st Qu. = −0.750, Median = −0.500, Mean = −0.572, 3rd Qu. = −0.500, Max. = −0.250). Analysis of negatively connoted terms within this dataset reveals a critical perspective and concerns associated with consumer behaviour and the agri-food chain.

Figure 4.

Analysis of sentiment distribution.

Terms like ‘aggressive’, ‘disappointed’, ‘impossible’, and ‘pandemic’ indicate a negative attitude and may reflect a concern or dissatisfaction with certain aspects of shopping and eating experiences. Words like ‘demand’, ‘damaged’, and ‘limit’ suggest concerns about the quality and affordability of food. In this respect, consumers may perceive a difficulty or limitation in meeting their demands, which contributes to the negative scores associated with these terms. Also, words such as ‘waste’, ‘risk’, and ‘problems’ may indicate concerns about managing food waste, product quality, or difficulties in the purchasing process. It is important to note that the negative attitudes evidenced by these terms can influence consumption behaviour and impact the relationship between consumers and the food industry.

From an academic perspective, these findings could be further investigated to better understand the factors contributing to negative perceptions and to propose solutions and improvements in the agri-food sector. Negative results indicate disapproval of certain aspects of food consumption, including concerns about waste, disappointment, or avoidance of certain products. Therefore, ‘aggressive’ is a negative or hostile attitude related to behaviour or practices associated with food; ‘avoidance’ indicates omission of certain aspects or food products, suggesting a preference for their exclusion from the diet; ‘disappointed’ indicates a state of disappointment, related to recent food experiences or products; whereas ‘waste’ represents a concern for food waste or may be associated with negative experiences related to food management.

Neutral sentiment scores, with a value of 0, indicate the absence of a pronounced sentimental orientation in the analysed text. The neutral and objective context of the discussion suggests that the subject is examining various aspects of the agri-food chain, without giving a clear evaluation or a specific sentiment (positive or negative). A detailed interpretation of the results highlights the following significant aspects: firstly, the predominance of neutral scores (0) for most terms underlines the absence of a strong positive or negative connotation. Terms such as ‘acceleration’, ‘access’, ‘activities’, ‘buy’, ‘chain’, ‘consumer’, and ‘consumption’ describe neutral aspects focusing on various stages, actions or elements involved in the food chain. Second, objectivity is evidenced by the absence of significant sentiment scores, indicating an informative and factual approach. The text appears to present facts, information, and concepts without expressing a subjective opinion or strong evaluation. In addition, the thematic diversity of terms reflects a comprehensive analysis of the agri-food chain, covering aspects of production, distribution, consumption, and consumer behaviour. In this context, terms such as ‘COVID’, ‘pandemic’, ‘country’, ‘daily’, and ‘current’ indicate a focus on the current context, including the impact of the pandemic on the agri-food chain and changes in consumer behaviour. In conclusion, the analysis of terms suggests that the text takes an informative and balanced perspective on the agri-food chain, providing the reader with an objective basis for forming their own opinion or expressing their own sentimental reaction.

Positive sentiment scores range from 0.100 to 1.000, with an average of 0.578. This suggests the presence of positive feelings in the text (Min. = 0.100, 1st Qu. = 0.400, Median = 0.600, Mean = 0.578, 3rd Qu. = 0.800, Max. = 1.000). The results of the analysis of positive words provide an encouraging and favourable outlook on consumption behaviour and the agri-food chain. Terms such as ‘afford’ and ‘appreciate’ suggest a practical approach and recognition of the value of food among consumers. This underlines the importance not only of quality but also of affordability, indicating a balance in consumption behaviour. Keywords such as ‘balanced’, ‘healthy’, and ‘sustainability’ reflect increased attention to healthy and sustainable food choices. Consumers seem to be shifting their preferences towards a balanced lifestyle, prioritising products that contribute to their personal well-being and environmental sustainability. Also, words like ‘worth’, ‘guarantee’, and ‘satisfy’ indicate consumer confidence in the quality of food products. This can play a key role in developing a positive relationship between consumers and producers, highlighting the importance of quality in meeting consumer needs and expectations. In conclusion, the results indicate a predominantly positive consumer view of the agri-food chain, highlighting key issues such as affordability, health, sustainability, and quality.

This positive outlook can influence purchasing decisions, helping to promote sustainable practices and strengthen a positive relationship between consumers and the other actors of the chain. Positive results reflect a favourable attitude towards food experiences, product quality and concerns for health and sustainability through the following words: ‘afford’, which suggests that the subject perceives food to be accessible and reasonably priced, thus contributing to a positive attitude towards consumption; ‘appreciated’ indicates a positive evaluation or gratitude, possibly related to the quality or service offered in the food context; ‘healthy’ designates an emphasis on health and suggests that the subject has preferences for healthy food choices; ‘sustainability’ shows a concern for long-term relation to food, indicating an increased awareness of environmental impact. Based on this analysis, word knowledge/identification is obtained, providing significant clues about the perceptions and attitudes expressed in the text, and providing insight into how subjects interact and perceive the food domain.

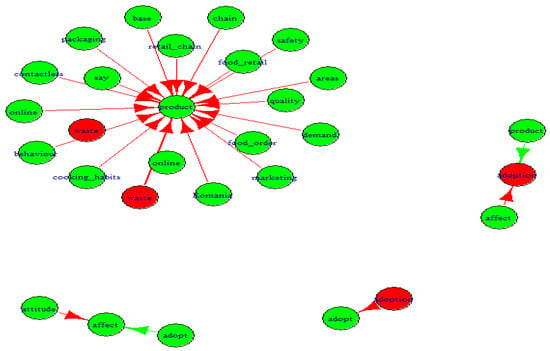

The analysis progressed by measuring word associations, and the findings are presented in Figure 5. This association matrix, through qualitative analysis, enables the identification of connections between concepts based on their occurrence in the texts. It assesses the frequency of one concept in relation to another within the provided answers.

Figure 5.

Word association matrix 1—IGRAPH (The figure is created on a core structure. The complete Figure 5 is attached in the Appendix A (Figure A1)). With red are the most important elements, with green the less important ones.

The matrix cells contain an association measure, like a correlation coefficient or a chi-square value, signifying the strength and direction of the relationship between concepts [40]. Since, in this context, correlation coefficients typically range between −1 and 1, as suggested by the literature [40], the words employed in the interview guide help characterise consumer behaviour and the agri-food chain. Regarding the matrix, the diagonal values are uniformly 1, which is anticipated since each variable is perfectly correlated with itself.

In addition, a significant number of the off-diagonal values are also 1, indicating mutual correlations between variables (concepts). Regarding notable correlations, there is a discernible moderately positive association of the variable ‘online’ with most other concepts. This suggests that online behaviour may be closely related to other aspects of consumer behaviour in the context under analysis. One notable aspect is the significant negative correlation between the variable ‘product’ and ‘adoption’. This relationship indicates an inverse association between product adoption and the concept of ‘product’. Detailed analysis of the specific context may provide more clarity in interpreting this relationship.

Strong correlations were observed between the variables ‘adopt’, ‘affect’, ‘attitude’, and ‘base’. This indicates a significant coherence between these concepts, suggestive of a unified meaning in the context of the text under analysis. In distinct clusters of correlations, there was a strong relationship between ‘food retail’, ‘retail chain/chain’, and ‘contactless’. This association suggests that changes in pandemic consumer behaviour may be closely related to these concepts, such as increased use of contactless technology and food shopping preferences. Analysis of the correlations between different concepts relevant to agriculture and marketing reveals significant interconnections between these issues. Firstly, a strong association is observed between ‘stage’ and ‘livestock’, suggesting that stages or phases, perhaps of a process or event, are closely related to livestock activities. In the sphere of agricultural activities, the term ‘agricultural’ is found to be well correlated with ‘marketing’, indicating a significant link between agricultural practices and marketing strategies. This result underlines the impact that decisions taken in the agricultural sector can have on the way products are promoted and marketed.

Packaging and marketing are closely interlinked, suggesting that the way products are packaged and presented significantly influences marketing strategies. A diverse group of concepts including ‘activities’, ‘actors’, ‘coordination’, ‘distributors’, ‘efficiency’, ‘ensure’, ‘farms’, ‘good’, ‘improve’, ‘inputs’, ‘retailers’, ‘suppliers’, and ‘sustainability’, are all strongly correlated with ‘marketing’. This result highlights the diversity of factors influencing marketing practices in the agricultural context, from coordination of activities to operational efficiency, sustainability, and interactions with various industry actors. Regarding ‘mixed content’, the concepts of ‘case’, ‘initial’, and ‘stage’ are significantly correlated, suggesting that these specific processes are closely related to the mixed content under analysis. It is also worth noting that ‘marketing’ has a strong correlation with ‘packaging’ and a moderate correlation with ‘storage’. This indicates that marketing strategies have a significant impact not only on product packaging, but also on storage aspects. These observations highlight the importance of certain variables, such as ‘online’ and ‘food retailing’, in understanding consumer behaviour. The correlation of 0.813 between ‘quality’ and ‘safety’ suggests that perceptions of the quality of a product or service may be correlated with safety issues. For example, food products perceived as high quality may also be associated with high safety standards. ‘Areas’ and ‘say’ have a correlation of 0.8125. This may suggest a significant association between specific areas and opinion or communication patterns. For example, certain geographical areas may be associated with certain opinions or way of speech. The analysis shows that there is a strong correlation of 0.894 between ‘Romania’ and a number of words such as ‘agri-food’, ‘community’, ‘course’, ‘economy’, ‘encourage’, ‘exist’, ‘far’, ‘foreign’, ‘fortunately’ and ‘prefer’. This may suggest that there is a significant connection between Romania and these concepts. The correlation of 0.8152 between ‘demand’ and ‘becoming’, respectively, as well as ‘demand’ and ‘behaviour’, indicates a significant association between demand and these concepts (changes in demand are correlated with developments or changes in consumer behaviour).

More specifically, a correlation analysis in the context of ‘food waste’, ‘cooking habits’, and ‘food order’ provided insights into the relationships between these key aspects of eating behaviour. A positive correlation of 0.8303942 was obtained between ‘food waste’ and ‘cooking habits’. This correlation indicates that the way people cook can influence the amount of wasted food generated. For example, more efficient cooking practices or careful planning of ingredients can help reduce waste. The very strong correlation of 0.948 between ‘food waste’ and ‘food order’ suggests a significant link between the way food is ordered and the amount of food waste generated. This result indicates that ordering options, such as the quantity and type of food ordered, can influence the level of food waste. For example, ordering the right portions or managing stocks efficiently can help reduce food waste. The correlation of 0.845 between ‘cooking habits’ and ‘food order’ indicates a significant association between cooking habits and how people order their food and that individuals’ cooking preferences and practices may influence their ordering choices. For example, someone with healthy cooking habits may tend to order the type of food that aligns with these preferences. Taken together, these correlations highlight the complexity of the relationships between ‘food waste’, ‘cooking habits’ and ‘food order’. Understanding these interconnections can provide valuable insights for tailoring order offerings to consumer needs and preferences. Regarding the relationship between the agri-food chain and ‘food waste’, the correlation of 0.894 indicates a significant connection between these two terms. This result may suggest that the way the agri-food chain manages the production, distribution, and sale of food may influence the amount of food waste generated. At the same time, food waste issues are likely to have an impact on the way the agri-food chain structures its operations. In terms of ‘cooking habits’, the similar correlation of 0.894 shows that there is a significant link between the agri-food chain and consumer cooking preferences or practices. This suggests that the way food is produced, packaged, and marketed in the agri-food chain may influence individuals’ cooking choices and habits. Also, the correlation of 0.894 between the agri-food chain and ‘food order’ highlights the link between how the agri-food chain responds to food demands and the choices made by consumers in placing orders. This underlines the importance of the adaptability of the agri-food chain to changing consumer preferences and trends. In conclusion, these complex correlations reveal significant interdependencies between the agri-food chain and consumer food behaviour. It is essential to continue exploring these relationships in order to develop more effective agri-food strategies adapted to the current needs and demands of society. The analysis of word associations led to the creation of a correlation matrix, a graphical representation of the relationships between terms. This matrix, noted as ‘undirected and unweighted’, contains 559 unique nodes or terms and 156,229.5 edges, reflecting the connections between them. This indicates a complex network of associations between terms identified in the dataset.

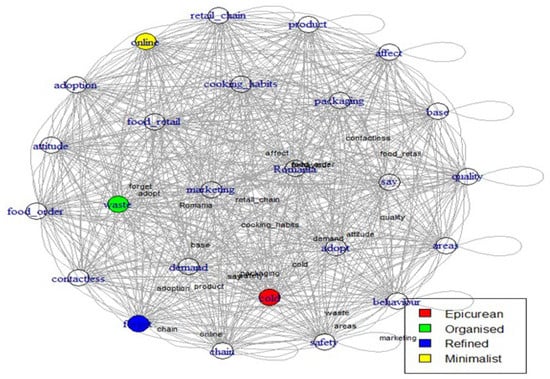

The matrix was created through the analysis of 223 distinct words in the dataset, revealing noteworthy connections among them (Figure 6). With a fill ratio of 0.999, the matrix is nearly comprehensive, suggesting that many elements are non-null. This suggests that there is association between many pairs of words, contributing to the complexity of the association analysis. There are 49,711 non-sparse elements in the correlation matrix out of a total of 49,729, which represents a fill ratio of 99.9638%. Each term in the matrix is limited to a maximum length of 16 characters, and the clustering algorithm came up with 2 separate groups of words in the dataset.

Figure 6.

Word association matrix 2—IGRAPH (The figure is created on a core structure. The complete Figure 6 is attached in the Appendix A (Figure A2)).

3.2. The Cluster Analysis

Further to the dataset analysis, four clusters were identified, described below (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clusters’ characteristics.

Cluster 1 was named Epicurean and totals 46 members with, respectively, a weight of 4.978, which suggests that it is a more predominant or influential cluster characterised by a greater concentration of pertinent information. Members of this cluster adopt a less frequent shopping pattern, indicating a preference for careful planning of their purchases. This attitude may reflect a more conscious and deliberate approach to the buying process. A significant characteristic of this cluster is increased involvement in home cooking. Key words such as ‘cook’, ‘home’, ‘myselfdaily’, and ‘homecooking’ suggest that these consumers are committed to the process of preparing food in their own households. This may reflect not only a preference for preparing food at home, but also an increased interest in carefully choosing ingredients. Members of this cluster also appear to rarely order food, indicating a greater likelihood of choosing home cooking over delivery alternatives. Mentions of supermarkets suggest that these consumers make their purchases in these types of stores, perhaps attracted by the diversity and expanded product choices offered by such facilities. Although there are no specific words about the agri-food chain, mentions of supermarkets and home cooking indicate some awareness of the processes in the food industry. On the topic of food waste, there are keywords such as ‘waste’, suggesting that these consumers may be aware of the problem. However, further details about specific attitudes and behaviours in reducing food waste could provide a deeper understanding.

In terms of food waste management at the household level, there is no clear information at this stage and further investigation through additional surveys or analysis may provide clarification on this issue. This interpretation provides a detailed insight into the consumption behaviour of Cluster 1 members, highlighting key aspects of their choices and indicating areas for further investigation. In other words, Cluster 1 members adopt a more infrequent shopping pattern, highlighting a preference for a deliberate approach to their purchases. This attitude reflects an increased awareness and careful planning of the purchasing process. A significant aspect of this cluster is their active involvement in home cooking. Cluster 1 members are dedicated not only to preparing food at home, but also to carefully selecting ingredients for an authentic culinary experience. Cluster 1 members also rarely order food at home, perhaps preferring to express their creativity in the kitchen over delivery alternatives. This cluster member refers to a person who pursues and appreciates the pleasures and joys of life, especially those related to the exquisite taste of food and drink. The Epicurean philosophy comes from the ancient philosopher Epicurus [47] and emphasises that the main source of human happiness lies in simple things and moderate pleasures, such as those derived from gastronomic joys, friendships, and community experiences. Members are people who seek to live a life full of aesthetic and sensory pleasures and other experiences that bring satisfaction and joy. Sentiment analysis shows that in Cluster 1 there are significant occurrences of feelings of surprise, anticipation, and joy within the surprise sentiment cluster, with a mean around 0.42. This indicates that Cluster 1 members are open to surprises and that they have varied and exciting experiences in their lives. These people may be open to novelty and are prone to be delighted by unexpected events full of freshness. In tandem, a sense of anticipation (Anticipation) appears with an average around 0.52. This suggests that cluster members are likely to anticipate and enjoy positive future events. The feeling of anticipation may reflect positive expectations and emotions associated with future events. Cluster 1 members may enjoy planning for and be enthusiastic about future occasions, including social experiences or other joyful activities. The joy sentiment has a mean around 1.26. This indicates that Cluster 1 members frequently experience positive and pleasurable states in their lives. These people probably enjoy simple pleasures such as cooking at home, social interactions, and other experiences that contribute to their overall well-being (a positive attitude toward life, enjoying events and experiences that bring satisfaction). These aspects contribute to shaping their profile as joyful, positive, and enthusiastic (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Cluster 1 specific features.

Cluster 2, referred to as the Organised, is made of 83 respondents and, respectively, has a weight of 8.601, which suggests that it is a more influential cluster with a higher concentration of meaningful data. Members adopt a systematic and organised approach to shopping and food preparation. It is observed that these consumers are used to planning their purchases, evidenced by keywords such as ‘daily’, ‘days’, and ‘list’. This attention to detail suggests a constant and deliberate concern for managing daily resources and needs. Home cooking is a frequent activity, illustrated by terms such as ‘nevercook’, ‘fast’, and ‘breakfast’. These consumers assume the role of cook in their own household and show a preference for preparing food at home, perhaps with health and control over ingredients in mind. Ordering food at home is a rare occurrence, indicating that members of this cluster prefer to manage their own food preparation. This choice may be related to the desire to have control over ingredients and cooking style. Supermarkets are a frequent source of supply for these consumers. Preference for sourcing may indicate both a pragmatic attitude and an efficient choice in terms of product quality and affordability. This community shops regularly, plans and cooks at home consistently. This organised way of approaching culinary matters highlights a meticulous attitude and commitment to a well-planned lifestyle.

Members of the Organised Cluster show a particular attention to managing food waste and the food-ordering process. The systematic and organised approach is also reflected in the way these consumers manage food to avoid waste. Cluster 2 members are aware of the importance of reducing food waste. Terms such as ‘throw’, and ‘waste’ indicate a concern for using food efficiently and minimising unnecessary disposal. This behaviour suggests a responsible attitude toward food resources and an effort to help reduce environmental impact. Cluster 2 members prefer to avoid frequent ordering of food at home, as indicated by terms such as ‘orderrarely’ and ‘oftenrarely’. This choice may be influenced by a desire to manage their own food preparation, thus having control over the ingredients, taste, and quantity consumed. This option can also help reduce the packaging waste associated with home food delivery. The Organised Cluster stands out for its awareness of food waste and preference for home cooking rather than ordering food home frequently. Members of the Organised Cluster are very careful and organised not only in their food shopping and preparation, but also in their perception of the agri-food chain. Although there are no specific words related to describing the agri-food chain, certain elements of their behaviour give clues about their relationship with this. Consumers in this cluster seem to value convenience and efficiency in sourcing food, suggesting a trust in supply chains and suppliers such as supermarkets. Efficient planning and purchasing indicated by the words ‘daily’, ‘days’, and ‘list’ among consumers in this cluster highlight an organised way of planning and purchasing their food. This may reflect an understanding of the steps in the agri-food chain and a desire to manage food and resources efficiently. This cluster expresses not only concern for food quality, but also an awareness of the importance of the agri-food chain in delivering these products from farm to fork.

The Organised Cluster, defined by consumers who adopt a well-planned lifestyle, reflects a meticulous approach to food shopping and preparation. This is evidenced by attention to details such as making shopping lists and frequent home recipes. Anticipation having a mean around 1.18 is a key element in this cluster, suggesting that its members prepare carefully for future events or activities related to food consumption. Careful planning of shopping and cooking indicates a constant and deliberate concern for efficient management of resources and daily needs. Enjoyment is an important aspect with a mean around 1.45, suggesting that Cluster 2 members consistently experience positive states, especially in the context of cooking activities and careful planning. This feeling could be associated with the satisfaction derived from preparing and eating their favourite foods, contributing to an overall enjoyable experience. Surprise is present to a lesser extent with a mean around 0.73, indicating a preference for an organised and planned way of life with less surprise. Cluster 2 members seem to avoid unexpected elements in their eating experiences, choosing stability and control. Appreciation for routine and planning contributes to building strong confidence in their personal choices and food processes. In conclusion, the Organised Cluster reflects a group of consumers who adopt a structured lifestyle based on anticipation, joy, and confidence in their own choices (Figure 8). This organised lifestyle is reflected in their attention to detail and deliberate approach to daily activities related to food consumption.

Figure 8.

Cluster 2 specific features.

Cluster 3, named Refined, counts 74 participants with, respectively, a weight of 7.638, which suggests that it is a more influential cluster with high concentration of relevant information. The Cluster 3 members show a high level of attention and refinement in food management and in their relationship with the agri-food chain. Analysis of this cluster in the context of food waste, home cooking, grocery spending and food ordering reveals a rare and sophisticated profile. Members of this cluster show a caring approach to food waste. Terms such as ‘never’, ‘occasionally’, and ‘little’ indicate a careful and responsible attitude toward food use and preservation. Presumably, these consumers carefully plan their menus and quantities to minimise food waste, indicating a commitment to sustainability and efficient use of resources. This cluster is notable for the high frequency of home cooking. With terms such as ‘cooking’, ‘kitchen’, and ‘weekly cook’, these consumers value the process of cooking and organise their routine around it. This behaviour may reflect a passion for preparing food at home with an emphasis on freshness and quality. Consumers in this cluster have a mindful approach to spending on groceries.

Terms such as ‘grocery’, ‘supermarket’, and ‘week’, indicate a regular frequency of purchases, but with attention to the details of shopping lists and ingredient selection. These consumers may seek quality and diversity, with a preference for fresh ingredients and products from local producers. The cluster uses words like ‘pizza’, ‘sushi’, and ‘app’ in the context of food orders, indicating a variety of culinary choices. This suggests that despite their ability to cook at home, these consumers also value the options offered by restaurants and food delivery services. Looking at the agri-food chain, the mention of ‘producers’ market’ and ‘Kaufland’ indicates an attention to diverse sources of supply, including directly from producers and through supermarkets. The cluster represents a sophisticated community that skilfully integrates home cooking with a careful selection of ingredients and an appreciation for the diverse culinary options offered by restaurants and delivery services. The cluster describes those refined consumers who approach food with an attention to detail. These individuals not only cook themselves with passion, but also shape their dining experience through carefully selected purchases and varied food-ordering options. Therefore, they are named Intuitive Culinary consumers who not only prepare food but savour every aspect of this sophisticated dining experience.

Sentiment analysis results in identification, anticipation is a key element in this cluster, with a significant average around 1.57. This suggests that members of this cluster exhibit a great deal of thoughtfulness and planning when it comes to shopping and cooking activities. Enjoyment is moderately present, with a mean around 1.24. This reflects that cluster members experience positive states and satisfaction in the context of cooking activities, such as cooking at home and careful selection of ingredients. Surprise is encountered less frequently in this cluster, with a relatively low mean of around 0.95. This indicates a preference for a more planned and organised lifestyle, with less emphasis on the ‘surprise factor’ in culinary experiences. Confidence is a consistent issue, with an average around 1.29. It highlights the confidence that cluster members have in their decisions and their organised approach to shopping and cooking. Overall, members of the Intuitive Culinary Cluster adopt a lifestyle characterised by careful planning, anticipation, and enjoyment of refined cuisine (Figure 9). The occurrence of surprise is low, suggesting a preference for stability and control in their eating experiences.

Figure 9.

Cluster 3 specific features.

Cluster 4, the Minimalist, counts 20 members, with, respectively, a weight of 2.228, which suggests that it is a dominant cluster taking a practical and minimalist approach to food management and interaction with the agri-food chain. The analysis of this cluster in the context of food waste, home cooking, shopping and food ordering highlights a simplified and efficiency-oriented lifestyle. Terms such as ‘use’, ‘enough’, and ‘takeout’ indicate an approach to food resources based on necessity and minimalism. These consumers may adopt strategies to use food efficiently, avoiding excessive purchases and managing their consumption pragmatically. The Minimalists report a moderate frequency of cooking at home, suggesting that members prefer quick and simple solutions. Terms such as ‘home usually’ and ‘once a week’ indicate a pragmatic approach to cooking at home, perhaps particularly at weekends or at certain times of the month. Consumers in this cluster take an efficient approach to shopping.

Terms such as ‘shops’, ‘purchases’, and ‘via’ suggest that Cluster 4 members make carefully managed purchases, possibly focusing on essentials and avoiding excess. Likewise, the mention of ‘takeout’ indicates resorting to food-ordering options to supplement their diet, thus avoiding the extra effort associated with complex cooking. Although there are no specific details about the agri-food chain, the mention of ‘city’ and ‘shops’ suggests that these consumers might rely on local and commercial sources to meet their food needs. The presence of terms such as ‘group’ may also indicate a collective buying attitude or participation in communities that facilitate efficient purchasing. The Minimalist Cluster represents a pragmatic community that adopts a simplified lifestyle oriented towards efficiency and judicious management of food resources. The cluster describes consumers who approach food and shopping with a pragmatic spirit. These individuals optimise their consumption and prefer simple solutions based on essential needs. The cluster can be called ‘Efficient Essentialists’ reflecting their practical spirit and focus on efficiency in every aspect of their interaction with food and the agri-food chain.

Sentiment analysis adds further insight, revealing that Cluster 4 members generally experience positive states with significant confidence in their own food choices and decisions. Low levels of surprise indicate a preference for a well-planned and organised lifestyle within this essential and effective community. Anticipation with a mean around 0.83 indicates that members of this cluster exhibit balanced anticipation about their cooking and shopping activities, indicating a planned but not extreme approach. This suggests conscious preparation for their experiences without reaching intense levels of anticipation. Joy with a mean around 0.98 indicates a significant level of joy within this cluster and shows that members frequently experience positive states during their food and shopping activities. Appreciation for these experiences contributes to their characterisation as being happy and satisfied. Surprises are at around 0.24. This indicates members’ preference for a planned and organised lifestyle, minimising unexpected items. They minimise their anticipations of unexpected events, choosing a calculated and controlled approach. Confident with an average around 0.93 in their own choices, Cluster 4 members adopt a pragmatic approach to shopping and cooking. Cluster 4 stands out for a pragmatic approach to food management and interaction with the agri-food chain. With moderate anticipation, these consumers prepare for their culinary and shopping activities while showing a significant level of joy in these experiences. The preference for a planned and organised lifestyle is evident in the decrease in surprises. These consumers rely on bare necessities, avoiding excesses and adopting a responsible attitude towards food waste. Thus, the Efficient Essentialist Cluster represents a community with a balance of moderate anticipation, expressed joy, low surprise, and constant confidence, reflecting a planned and efficient way of life in managing aspects of food and shopping (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Cluster 4 specific features.

The cluster density stands at 0.589, signifying that the clusters exhibit relatively similar densities. Purity registers at 0.77, denoting a high level of agreement within the clustering. The low entropy value of 0.29 suggests the effectiveness of the clustering in capturing patterns in the data, resulting in meaningful and distinct clusters. However, determining a suitable threshold for ‘good’ performance relies on the specific application and available truth. An F-measure of 0.805 indicates a relatively good clustering performance in capturing true labels or ground truth.

Significant trends and patterns were identified, and they provide a detailed picture of consumer preferences and practices. Most participants revealed a diversified consumption behaviour, with an emphasis on cooking at home and, at the same time, the use of home food-ordering services. This amalgam of practices suggests an increased adaptability of consumers to their dynamic dietary needs and preferences. This versatility in approach may influence the food industry and delivery services, indicating the need for varied and personalised offerings.

Perceptions of the agri-food chain are diverse, ranging from appreciation of local chains and farmers’ markets to the use of supermarkets and online ordering services. This diversity indicates an awareness of the origin of food and the varied options available to consumers. However, to meet different expectations, food industries can benefit from flexible strategies that promote both sustainability and affordability. A significant aspect revealed in the participants’ responses is the awareness and concern about food waste. Participants identified the causes of wastage, such as excessive shopping or inefficient storage management. Potential solutions, such as careful planning of purchases and responsible management of food resources, could help reduce negative environmental impacts and save resources. Regarding managing food waste at household level, participants highlighted various approaches, from composting and recycling to careful portion planning. This variety of practices shows that there is a growing awareness of the importance of reducing food waste and an openness to innovative ways of waste management.

From the figure above (Figure 11), the significant percentages associated with feelings of anticipation (24.30%) and joy (30.63%) reflect a generally positive atmosphere among participants regarding shopping habits and ordering food at home. This result suggests that engaging in these activities brings a high level of positive expectation and satisfaction. The high percentage associated with confidence (30.89%) indicates that participants are confident in their shopping choices and food management, including how they handle leftovers. This confidence may be crucial in the context of sustainability and reducing food waste, as it can influence decisions related to food purchasing and storage. The significant percentage of surprise (13.42%) suggests that there is some variety and unexpected elements in shopping and ordering habits. This presents an opportunity for the industry to tailor and personalise experiences to better meet the diversity of consumer preferences and expectations.

Figure 11.

The sentiment distribution analysis.

Additionally, it is observed that in the study people show reduced negative emotions. Low percentages associated with negative emotions such as anger, disgust, fear, and sadness (all below 1%) indicate a minimal prevalence of these emotional states in the context of cooking and food waste management. This positive aspect may contribute to a more pleasant and efficient environment in managing food resources. Sentiment analysis adds an interesting perspective and highlights the connections between emotions, consumer behaviour, and practical aspects of food management. These findings can be used in the implementation of strategies and initiatives to support sustainability and reduce food waste. In the research on consumer behaviour and the agri-food chain, participants provided valuable information on their shopping habits, food ordering at home and cooking habits. Analysing the percentages associated with different sentiments provides a deeper understanding of how individuals interact with food and the food chain. Shopping habits and ordering at home reveal a significant percentage of respondents who mentioned feelings of anticipation, joy, and confidence. These positive emotions likely indicate a pleasant experience in the process of selecting food and engaging with home delivery services. Surprise was also noticed to a significant extent, suggesting unexpected items or variations in shopping and ordering habits. In terms of cooking and food waste management habits, low percentages associated with feelings such as anger, disgust, fear, and sadness could indicate a lower prevalence of these emotions around cooking and food waste management. In the context of sustainability and food waste reduction, positive perceptions of the shopping and cooking process can be a starting point for education and raising awareness of food waste reduction. Understanding the emotions associated with ordering food at home can assist in optimising services and providing more effective solutions of sustainability.

Consumers who are informed and interested in sustainability issues can encourage producers and retailers to adopt more responsible practices, thereby contributing to reducing the environmental footprint of the entire food chain.

Firstly, informed and sustainability-conscious consumers can have the potential to exert positive pressure on producers to adopt more sustainable farming practices. Choosing to support producers who implement environmentally friendly techniques and respect ethical standards can contribute to a paradigm shift in industry. Also, retailers who perceive this shift in consumer preferences may be motivated to review their supply chains and integrate more socially and environmentally responsible practices. This may include initiatives such as reducing unnecessary packaging, promoting local production, and managing stocks efficiently. Another crucial issue is influencing the food chain through consumer demand for sustainable and ethical products. By supporting these products, consumers can help increase the supply of sustainable options and create a more environmentally friendly market. This, in turn, can lead to a reduction in negative impacts on natural resources and biodiversity. In the long run, a positive perception of the purchasing process can create a virtuous circle in which consumers, producers and retailers work together to build a fairer and more sustainable agri-food chain. This collaborative effort can bring benefits for the environment, local communities, and society as a whole.

4. Discussions

By employing word cloud and sentiment analysis on the gathered data, this study aims to assess the extent of consumer grievances. Individual reviews have been classified into positive and negative sentiments, specifically related to food waste. Negative sentiments can be further categorised into distinct classes (the four main evidenced clusters), including food purchasing practices, cooking techniques, food quality, and cost per ingredient. This categorisation helps estimate the significance of the financial factor within the Food Loss and Waste (FLW) phenomenon.

This information provides valuable insights for agri-food chain organisations, allowing them to identify specific areas where issues are more prevalent. For instance, if negative sentiments arise from problems like bad labelling or imported ingredients, food providers and distributors may need to address supply chain adjustments. Additionally, logistics concerns can be addressed by assessing the number of vehicles and delivery personnel required for the growing back-to-local trends, as consumers express their preference for consuming seasonal vegetables or fruits from their own regions.

In cases where consumer feedback falls under the service category, a focus on improving service levels becomes crucial, especially in the HoReCa sector. Regarding food delivery, potential issues such as inadequate packaging or spillage require resolutions at individual restaurants, and organisations should monitor establishments contributing to negative reviews due to food quality.

Conversely, positive sentiment topic categorisation can be employed to recognise and reward distribution chain staff or restaurants. It can also serve as an incentive for local farmers to enhance their technological capabilities for larger stocks to meet increasing demand.

In the light of research on consumer behaviour and the agri-food chain, the results obtained have been highlighted and developed by several relevant scientific papers. A significant study [48] addressed the causes, impacts and proposals related to food waste and the paper provided a broad perspective on the problems associated with food waste, reinforcing the importance of analysing this issue from consumer perspective. In parallel, Young et al. [49] and Jagau et al. [50] have made significant contributions to understanding consumer food and waste management behaviour; their study provided detailed insights into the factors influencing food waste among UK consumers. Together, these scientific papers have anchored and validated this research findings, highlighting the importance of awareness and behaviour change to promote sustainability in the agri-food chain and reduce food waste.

In addition, the findings of the present study reflect a growing interest in the literature on the interconnection between individuals’ food behaviour and the dynamics of the agri-food chain [51]. These issues could be addressed in future studies on food sustainability, circular economy, food marketing and sustainable agricultural practices. Analysis of these relevant terms reveals the concerns and priorities of the participants, thus providing a basis for research and implementation of more responsible food practices.

Our research makes a significant contribution to the understanding of consumer behaviour and the dynamics of the agri-food chain, building on the fundamental findings of other relevant authors [52,53]. Consistency with keywords identified in the literature reinforces the validity of the chosen methodology, which was based on semi-structured interviews and text analysis. This suggests a validation of the results in the context of existing theories and findings, contributing to the knowledge foundation in the field of consumer behaviour and the agri-food chain. From an applied perspective, this congruence strengthens the basis for strategic decision-making in the food industry, ensuring a solid alignment with real consumer needs and preferences.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this research underscore the necessity for the agri-food sector and related services to respond to the varied needs and preferences of consumers. A tailored approach, based on sustainability and innovation, could be the key to success in delivering food products and services that meet the evolving expectations of the market. Continuous adaptation to the dynamics of consumer behaviour is essential, with an increased focus on the environmental and social aspects of the whole agri-food chain. This study provides a comprehensive perspective on the consumer landscape in Romania and suggests that future strategies should take account of this diversity among consumers and address their functional and emotional requirements.

There is a broad spectrum of approaches to shopping, home cooking and ordering, reflecting the adaptability and diversity of consumer needs. Across all clusters, consumers seek a pleasant and varied dining experience, indicating a concern not only for the functional aspects of food, but also for its aesthetic and taste components. This suggests that innovations in food preparation and plating can have a significant impact.

Concern about food waste and preference for local agri-food chains indicate an increasing awareness of sustainability among consumers. Thus, marketing strategies and offers highlighting environmental aspects can have a positive impact, too. The substantial variation in consumer behaviour underlines the need for flexibility in the approach of the food industry. Businesses in this sector would benefit from being adaptable to the requirements of a diverse public through tailored offers and services.

The mention of online ordering services and apps suggests that technology plays a significant role in the way consumers manage their food. Integrating technology into marketing and distribution strategies could bring significant benefits. There is a need for food education, particularly in terms of responsible shopping and food waste management. Educational campaigns and programmes could help raise awareness and promote sustainable practices.

Implementing innovative technologies to reduce losses in production phases was a need identified by consumers, as a promising direction. Encouraging donations to charities and promoting recycling to generate fertiliser or energy were recognised as sustainable practices. Regarding meal planning and responsible cooking, it was observed that encouraging weekly meal planning and promoting responsible cooking have a significant impact in reducing excessive shopping and food waste at the household level. Regarding responsible home ordering, it was observed that encouraging the use of ordering options that promote sustainable packaging and responsible waste management, as well as supporting online delivery platforms, is another key aspect in this equation. Monitoring and improving public policies were recognised as crucial elements in supporting and implementing these strategies at EU and national level. Involving local authorities, NGOs and governments in the development of effective policies is a necessity to create a favourable legislative framework.

The results of this study and sentiment analysis suggest that there is an increased understanding of the importance of strategies to promote sustainable eating behaviour. Implementing these strategies is a complex challenge, but a collaborative and educational approach can contribute significantly to creating a more sustainable environment and changing consumer attitudes and behaviours. These findings provide the foundation for an effective food chain and consumer behaviour management. To use these outcomes within a certain strategy plan, stakeholders are invited to develop and contribute to sustainability strategies, optimise the supply chain, minimise risk at every stage, adjust the offer to all categories of consumers, improve stock management, engage in recycling operations, and finally innovate in this challenging domain.

Although the results of this research provide valuable insights into individuals’ perspectives, experiences, and attitudes regarding food waste and loss [54,55,56], a series of limitations were identified, namely the use of the convenience sampling method and the social desirability bias (respondents provide answers they believe are socially desirable rather than reflecting their true beliefs or behaviours) [57]. Nevertheless, it is important to note that these limitations are commonly accepted in qualitative studies [58].

Author Contributions