Analyzing Exchange Rate Effects on Trade: Empirical Evidence

Abstract

1. Introduction

A Historical Review of Exchange Rate Liberalization and Its Impact on the Egyptian Economy

2. Modeling Approach and Description of the Database

2.1. Description of the Model

2.1.1. Equilibrium Real Exchange Rate

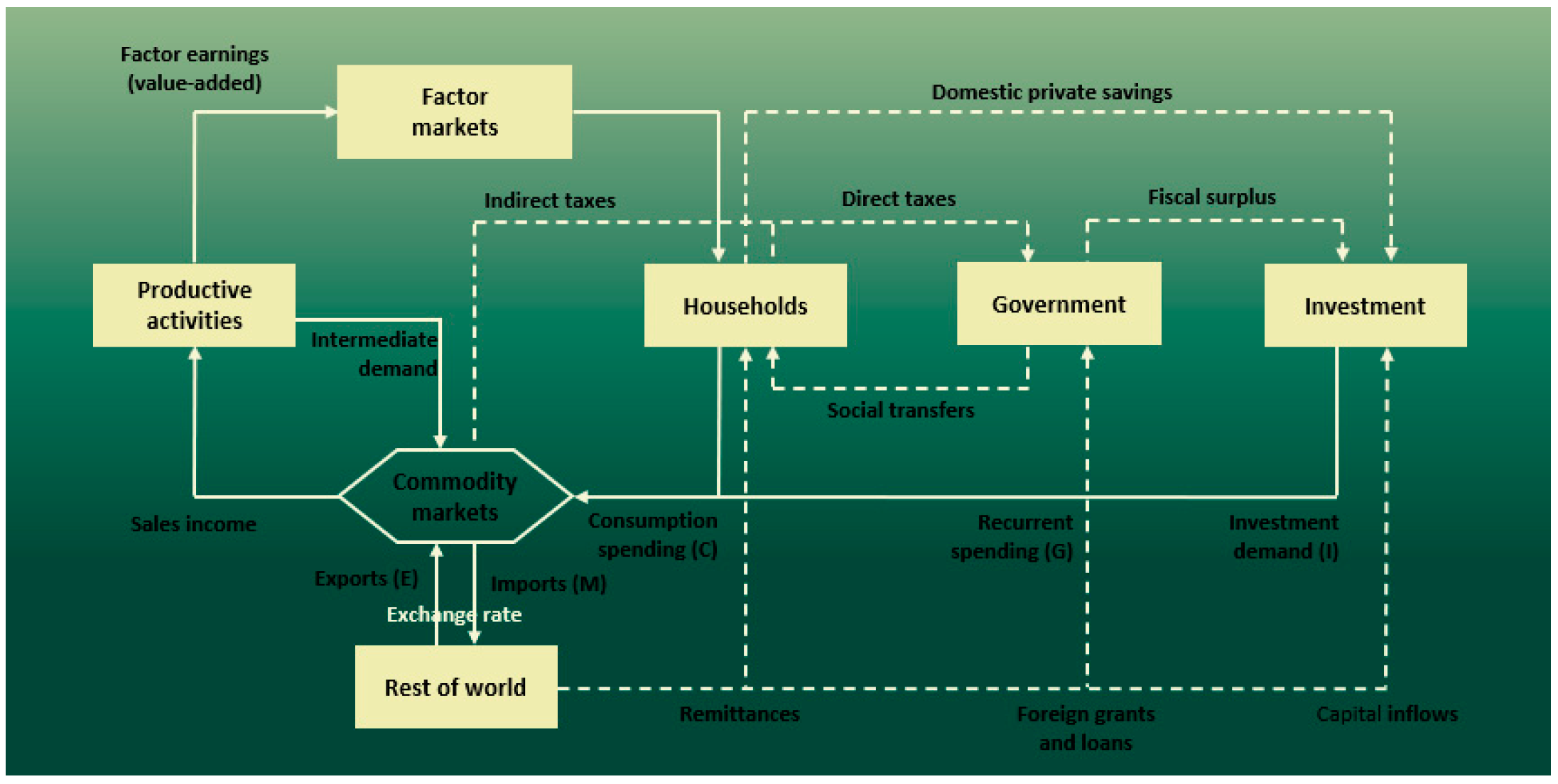

2.1.2. The CGE Model

2.2. Description of the Database

3. Policy Simulations

4. Results

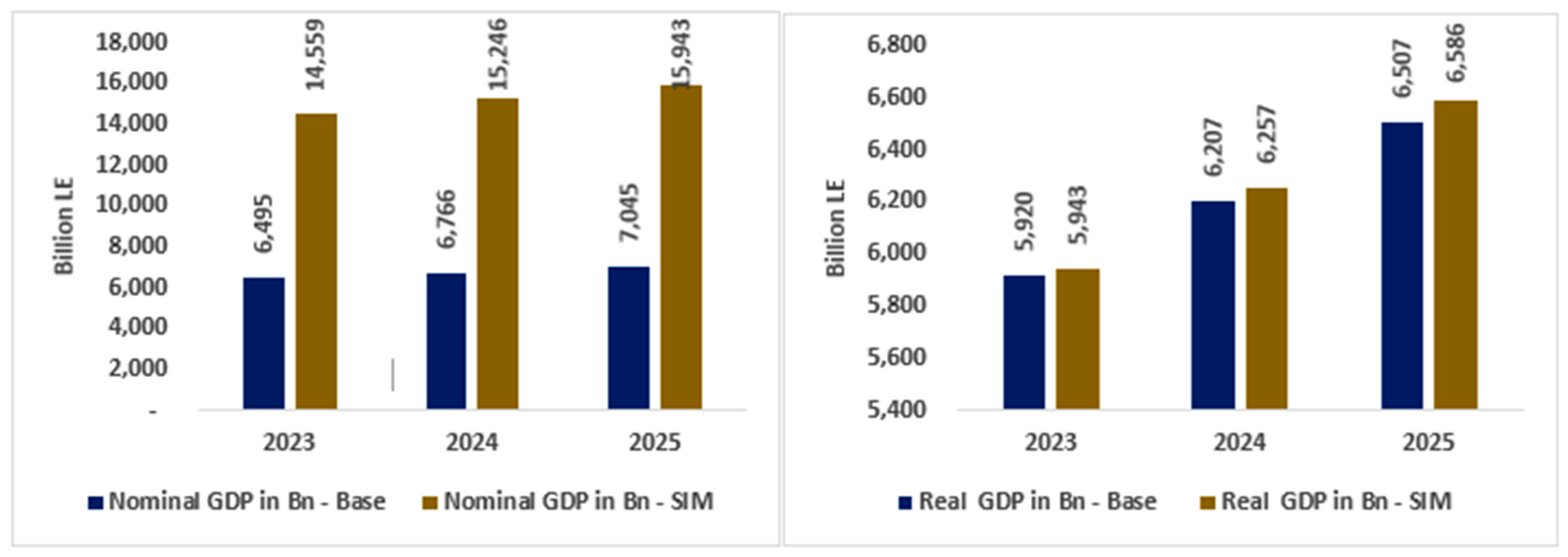

4.1. Baseline Scenario

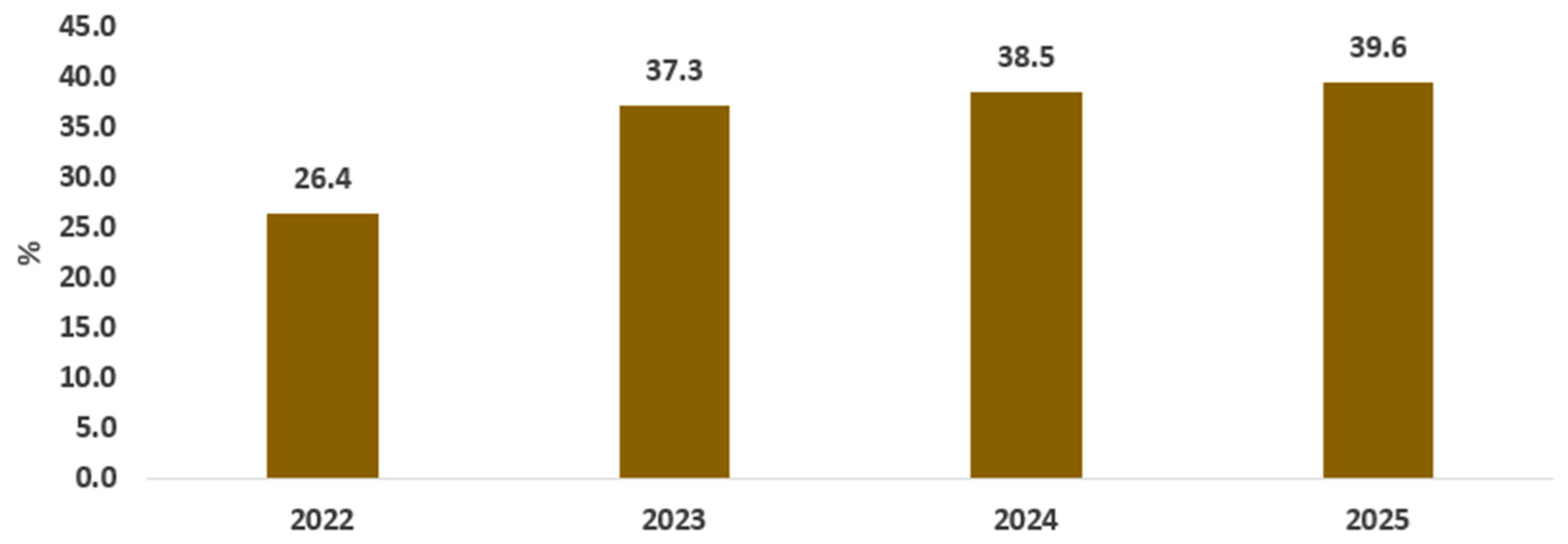

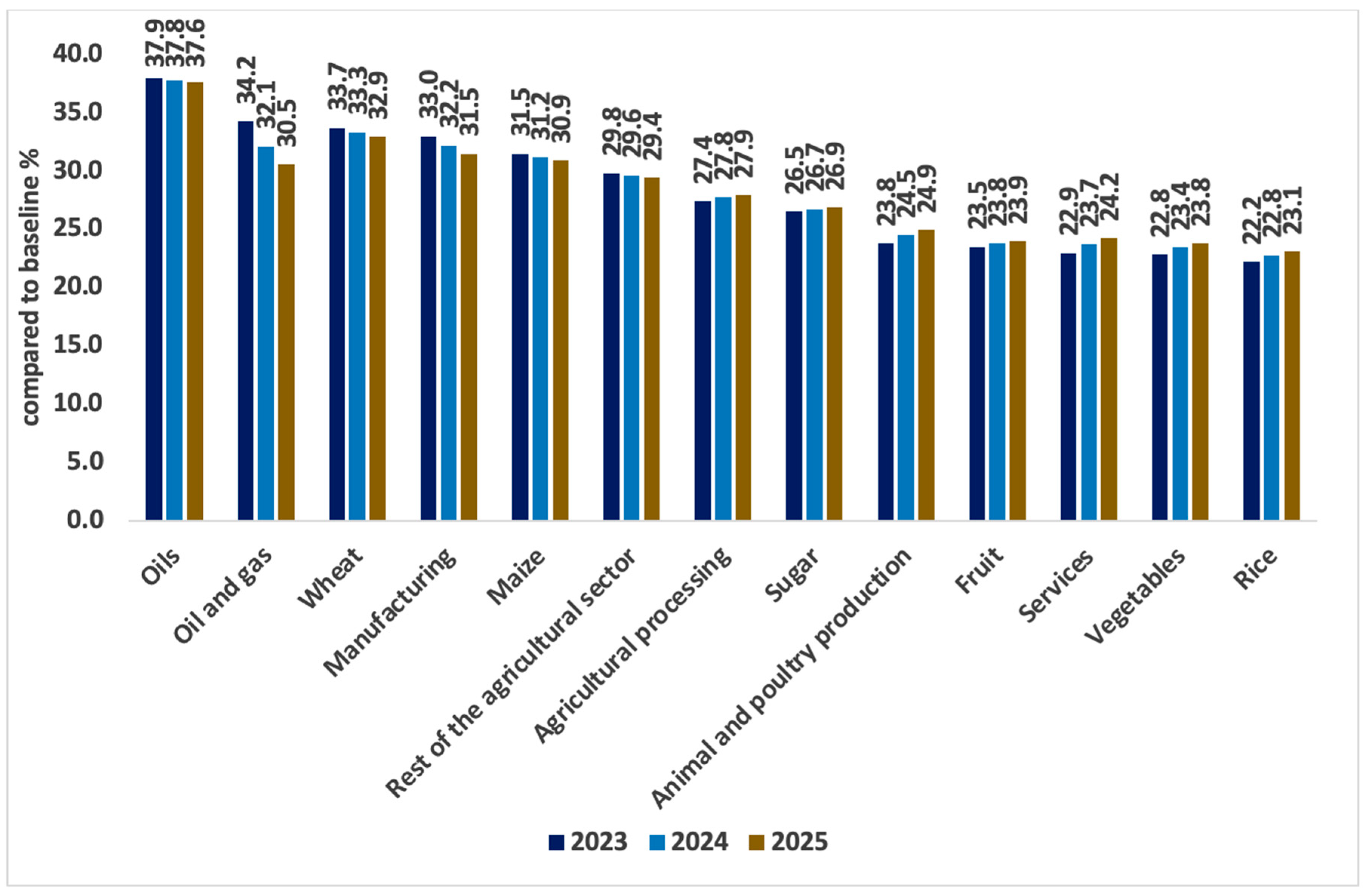

4.2. Simulation Scenario (the Impacts of Exchange Rate Devaluation Shocks)

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Oskolkov, A. Exchange rate policy and heterogeneity in small open economies. J. Int. Econ. 2023, 142, 103750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldeep, C.; Zaki, C. On the unfinished business of stabilization programs: A CGE model of Egypt. Middle East Dev. J. 2023, 15, 66–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pargaru, I.; Andra, M.; Vasilescu, R.A.; Platagea, G.S.; Dinu, M. Consequences of choosing the exchange rate regime on international trade. In Proceedings of the 30 Years of Economic Reforms in the Republic of Moldova: Economic Progress via Innovation and Competitiveness, Chișinău, Moldova, 24–25 September 2021; pp. 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Najafi Bousari, B.; Akbari Moghadam, B.; Hadizadeh Mirkelaei, A.; Bayat, N. Impact of exchange rates and inflation on GDP: A data panel approach consistent with data from Iran, Iraq and Turkey. Int. J. Nonlinear Anal. Appl. 2024, 15, 311–325. [Google Scholar]

- Abimbola Oyinlola, M.; Adeniyi, O.; Theophilus Kumeka, T. Dependence between foreign trade performance and exchange rate volatility: Panel ARDL approach. Croat. Rev. Econ. Bus. Soc. Stat. 2023, 9, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavi, S.; Leelavathi, D. Agricultural export and exchange rates in India: The granger causality approach. Int. J. Sci. Res. Publ. 2013, 3, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank Annual Report 2003. In World Bank Annual Report; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [CrossRef]

- The World Bank Annual Report 2006. In World Bank Annual Report; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2006. [CrossRef]

- Research Department-Central Bank-General-Annual Report and Balance Sheet-Governor’s Report-Drafts and Correspondence-Reserve Bank Annual Report-White Copy for Presentation to Parliament; Reserve Bank of Australia: Sydney, Australia, 30 September 2021.

- Mohamed, M. The Effect of Fiscal and Monetary Policy on Public Debt in Egypt. Master’s Thesis, The American University in Cairo, New Cairo, Egypt, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Bradshaw, G.W.; Orden, D. Granger causality from the exchange rate to agricultural prices and export sales. West. J. Agric. Econ. 1990, 15, 100–110. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, J.; Koo, W.W. Identifying Macroeconomic Linkages to U.S. Agricultural Trade Balance. Can. J. Agric. Econ./Rev. Can. D’agroecon. 2008, 56, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chebbi, H.E.; Olarreaga, M.; Zitouna, H. Trade openness and CO2 emissions in Tunisia. Middle East Dev. J. 2011, 3, 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šimáková, J. Assessing exchange rate sensitivity of bilateral agricultural trade for the Visegrad countries. Outlook Agric. 2017, 46, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Bank Annual Report 2022. In World Bank Annual Report; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Abu Hatab, A.R. Impact of Exchange Rate Volatility on The Performance of Egyptian Agricultural Exports Using A Vector Error Correction Model. J. Agric. Econ. Soc. Sci. 2016, 7, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabsigh, G.; Domaç, I. Real Exchange Rate Behavior and Economic Growth: Evidence From Egypt, Jordan, Morocco, and Tunisia. IMF Work. Pap. 1999, 99, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achy, L.; Sekkat, K. The European Single Currency and MENA’s Exports to Europe. Rev. Dev. Econ. 2003, 7, 563–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatab, A.A.; Romstad, E.; Huo, X. Determinants of Egyptian Agricultural Exports: A Gravity Model Approach. Mod. Econ. 2010, 1, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahloul, A.Q.M.M. The Egyptian Trade Policy Strategy of Development and The Global Trading System in The WTO Era. Egypt. Assoc. Agric. Econ. 2012, 22, 302–311. [Google Scholar]

- Massoud, A.A.; Willett, T.D. Egypt’s Exchange Rate Regime Policy after the Float. Int. J. Soc. Sci. Stud. 2014, 2, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, C.; Abdallah, A.; Sami, M. How Do Trade Margins Respond to Exchange Rate? The Case of Egypt1. J. Afr. Trade 2019, 6, 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benfica, R.; Cunguara, B.; Thurlow, J. Linking agricultural investments to growth and poverty: An economywide approach applied to Mozambique. Agric. Syst. 2019, 172, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doroodian, K.; Jung, C.; Yucel, A. Estimating the equilibrium real exchange rate: The case of Turkey. Appl. Econ. 2002, 34, 1807–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etta-Nkwelle, M. The Effects of Overvalued Exchange Rates on the Export Competitiveness of Less Developed Countries: Evidence from the Communaute Financiere Africane (CFA); ProQuest: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bénassy-Quéré, A.; Béreau, S.; Mignon, V. Robust estimations of equilibrium exchange rates within the G20: A panel BEER approach. Scott. J. Political Econ. 2009, 56, 608–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razin, O.; Collins, S. Real Exchange Rate Misalignments and Growth; National Bureau of Economic Research: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bouoiyour, J.; Rey, S. Exchange Rate Regime, Real Exchange Rate, Trade Flows and Foreign Direct Investments: The Case of Morocco. Afr. Dev. Rev. 2005, 17, 302–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toulaboe, D. Real exchange rate misalignment and economic growth in developing countries. Southwest. Econ. Rev. 2011, 33, 57–74. [Google Scholar]

- Decaluwé, B.; Lemelin, A.; Robichaud, V.; Maisonnave, H. PEP-1-t. In Standard PEP Model: Single-Country, Recursive Dynamic Version, Politique Économique et Pauvreté/Poverty and Economic Policy Network; Université Laval: Québec, QC, Canada, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Diao, X.; Thurlow, J.; Benin, S.; Fan, S. Strategies and Priorities for African Agriculture: Economywide Perspectives from Country Studies; Intl Food Policy Res Inst: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelgany, M. Determinants of Real Exchange Rate Evidence: From Egypt. J. Politics Econ. 2020, 7, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feyzioglu, T. Estimating the Equilibrium Real Exchange Rate: An Application to Finland. IMF Work. Pap. 1997, 97, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hosni, R.; Rofael, D. Real exchange rate assessment in Egypt: Equilibrium and misalignments. J. Econ. Int. Financ. 2015, 7, 80. [Google Scholar]

- Krugman, P.R.; Obstfeld, M. International Economics: Theory and Policy; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon, P.; Rimmer, M. Forecasting with a CGE Model: Does It Work? Centre of Policy Studies; IMPACT Centre Working Papers G-197; Victoria University: Melbourne, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Raouf, M.; Randriamamonjy, J.; Engelke, W.; Kebsi, T.A.; Tandon, S.A.; Wiebelt, M.; Breisinger, C. Regionalized Social Accounting Matrix for Yemen: A 2014 Nexus Project SAM; Intl Food Policy Res Inst: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Volume 21. [Google Scholar]

| Rural Households | Urban Households | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | 2023 | 2024 | 2025 | |

| Maize | −1.64 | −1.34 | −1.07 | −1.97 | −1.65 | −1.37 |

| Rice | 0.32 | 0.48 | 0.67 | −0.05 | 0.13 | 0.33 |

| Wheat | −2.11 | −1.79 | −1.51 | −2.42 | −2.09 | −1.80 |

| Oils | −1.35 | −1.05 | −0.78 | −1.70 | −1.39 | −1.10 |

| Vegetables | 0.19 | 0.34 | 0.51 | −0.20 | −0.03 | 0.16 |

| Fruit | 0.05 | 0.28 | 0.50 | −0.35 | −0.11 | 0.13 |

| Animal and poultry production | 0.00 | 0.20 | 0.45 | −0.57 | −0.35 | −0.08 |

| Oil and gas | −3.39 | −2.33 | −1.51 | −3.91 | −2.84 | −2.00 |

| Manufacturing | −3.09 | −2.44 | −1.87 | −3.63 | −2.96 | −2.38 |

| Services | 0.25 | 0.42 | 0.62 | −0.35 | −0.14 | 0.09 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ahmed, Y.N.; Alnafissa, M.; Negm, M.M.; Gharieb, Y.M.; Algarini, A.; Hassouba, T.A.-A. Analyzing Exchange Rate Effects on Trade: Empirical Evidence. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4177. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16104177

Ahmed YN, Alnafissa M, Negm MM, Gharieb YM, Algarini A, Hassouba TA-A. Analyzing Exchange Rate Effects on Trade: Empirical Evidence. Sustainability. 2024; 16(10):4177. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16104177

Chicago/Turabian StyleAhmed, Yosri Nasr, Mohamad Alnafissa, Mosatafa M. Negm, Yasmine Mohieeldin Gharieb, Abdullah Algarini, and Taghreed Abdel-Aziz Hassouba. 2024. "Analyzing Exchange Rate Effects on Trade: Empirical Evidence" Sustainability 16, no. 10: 4177. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16104177

APA StyleAhmed, Y. N., Alnafissa, M., Negm, M. M., Gharieb, Y. M., Algarini, A., & Hassouba, T. A.-A. (2024). Analyzing Exchange Rate Effects on Trade: Empirical Evidence. Sustainability, 16(10), 4177. https://doi.org/10.3390/su16104177