Abstract

Previous research in Western nations has established a clear connection between pro-environmental public opinion and clean energy transition policies aligned with Sustainable Development Goals 7 and 13. However, little is known about this relationship in East Asia, the most important region of the world in terms of carbon emissions. Using the International Social Survey Program and Taiwan Social Change Survey results from 2010 and 2020, this study examines public opinion in Taiwan on environmental issues, comparing it with opinion in a group of 18 OECD countries. Results show high but stable support for the environment and the energy transition in Taiwan over this period, with no indications of climate denial. However, willingness to make sacrifices for the environment is sharply lower among the lower half of the income distribution, highlighting existing socioeconomic disparities and inequality. Further, political engagement around environmental issues remains relatively low in Taiwan compared to engagement in the OECD comparison group. This disjunction suggests a unique model of public opinion and policy outcomes in Taiwan, which is clearly distinct from patterns in the West. Comprehending this model is vital, considering East Asia’s necessary role in a global clean energy transition.

1. Introduction

The growing severity of climate change impacts [1,2,3] has led to urgent global calls for action represented by the 2015 Paris Agreement [4] and the UN Sustainable Development Goals [5]. Despite these calls, the energy transition is lagging globally [6,7,8]. In particular, East Asia, responsible for a staggering 35% of global CO2 emissions [9], persists in a slow-paced energy transition. Why do East Asia’s advanced democracies, including Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan, lag behind in making the needed changes to their energy policies? Are the key obstacles to be found in public opinion, economic constraints, political barriers, or something else?

While efforts to address climate change must be global, much of the focus so far has been on Western countries [10]. Less attention has been paid to East Asia, even though the region is responsible for a higher share of emissions than the US and EU combined [9]. Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan have made only limited progress in reducing emissions, and each has received ratings of ‘poor’ or ‘very poor’ in the Germanwatch Climate Change Performance Index for many years [11,12]. Additionally, the per capita carbon dioxide emissions in the region are notably higher than the average in the European Union. In 2019, the year before the COVID-19 pandemic, the emissions from fossil fuel use and industry per person were measured at 8.8 tons in Japan, 12.5 tons in South Korea, and 11.5 tons in Taiwan. Although these figures are lower than the United States’ 15.7 tons per capita, they significantly exceed the European Union’s average of 6.5 tons per capita [13].

The reasons behind this delay are not understood. While existing theories often tie public policy to public sentiment, especially in democracies, the relationship between public opinion and energy policy in East Asia remains underexplored. A better understanding of the nature and role of public opinion in this critical region is important, both in explaining past performance and in evaluating options for future change. This study aims to bridge this gap by investigating public opinion on the environment in Taiwan and its influence on the nation’s energy policies.

1.1. The Lagging Energy Transition in Taiwan

Over the past decade, Taiwan’s energy policy has undergone significant reassessment in response to global and regional events. The 2011 Fukushima disaster prompted a reevaluation of energy strategies. This incident coincided with a period of intensified global focus on climate change, marked by the adoption of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by the United Nations in September 2015 and the Paris Agreement in December 2015. These initiatives set ambitious targets for nations to reduce their carbon emissions and spurred Taiwan to rethink its energy policies.

In response, Taiwan made a political commitment to phase out nuclear power, formalized in the April 2015 announcement by Taiwan’s Ministry of Economic Affairs (MOEA) that all operating nuclear power plants would be shut down by 2025. Then, shortly after the new president’s inauguration in May 2016, the MOEA unveiled its proposed 2025 electricity mix. According to the MOEA’s four-page presentation, the government aimed to achieve an electricity mix composed of 50% gas-fired power, 30% coal-fired power, and 20% renewable energy by 2025 (Table 1), eliminating nuclear power from the energy portfolio while simultaneously seeking to achieve a cleaner energy mix. This commitment was part of a broader attempt to reform Taiwan’s energy policies, which also included notable policy initiatives such as the ‘Pathway to Net-Zero Emissions in 2050’ strategy released in March 2022 and the proposed Climate Change Response Act [14].

Thus far, however, progress has been slow (Table 1). Data from Taiwan’s Bureau of Energy for the year 2020 indicates a mix of 45.0% coal, 35.7% gas, 11.2% nuclear, and 5.4% renewable energy [15]. Further, the ‘Pathway to Net-Zero Emissions by 2050’ plan, while aiming to achieve 60–70% renewable energy and introduce a carbon fee, lacks specific medium-term targets for 2030 and detailed action plans [14]. In the 2024 Climate Change Performance Index, Taiwan (‘Chinese Taipei’) showed further worsening in its environmental performance, descending to the 61st position out of 67 countries [16,17].

Table 1.

Sources of Electrical Power in Taiwan, 2010–2022 [15,18].

Table 1.

Sources of Electrical Power in Taiwan, 2010–2022 [15,18].

| Source | Year | Taiwan MOEA Target | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | 2022 | 2025 * | |

| Coal | 49.5% | 45.4% | 45.0% | 42.0% | 30% |

| Oil | 4.5% | 4.6% | 1.6% | 1.5% | |

| Natural Gas | 24.4% | 30.6% | 35.7% | 38.9% | 50% |

| Nuclear | 16.8% | 14.1% | 11.2% | 8.2% | |

| Renewable | 3.5% | 4.1% | 5.4% | 8.3% | 20% |

| Other | 1.2% | 1.2% | 1.1% | 1.1% | |

| Total | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

* Projected values.

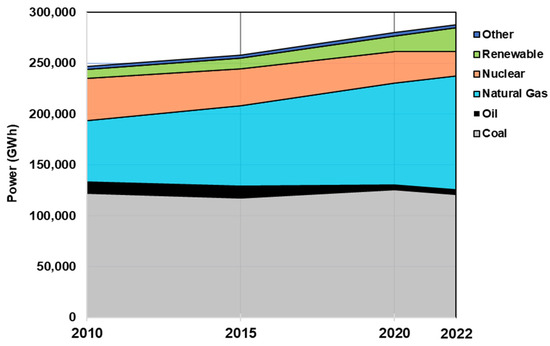

Further, despite a reduction in coal-generated energy from 49.5% to 42% of the total, the actual decrease in GWh generated by coal was only 1.08%, due to an overall expansion in electricity generation (Figure 1). When natural gas is included, the percentage of electricity from fossil fuel sources actually increased from 78.4% to 82.4%, while the percentage from non-carbon sources (renewable and nuclear) decreased from 20.3% to 16.5%. Even the goal of achieving a 50–30–20 energy mix (50% natural gas, 30% coal, and 20% renewable) by 2025 still implies a significant reliance on fossil fuels. On top of this, in 2022, MOEA Minister Wang Mei-Hua announced that Taiwan is unlikely to meet the 2025 target, and BoE forecasts now predict that renewables will account for 15.2% in 2025 [19]. Finally, there is no clear indication of how Taiwan plans to completely transition away from coal or achieve a net-zero status by 2050, as quantitative energy conservation targets are absent from Taiwan’s current energy transition agenda.

Figure 1.

Sources of Electrical Power in Taiwan (GWh), 2010–2022 [15].

What explains this limited progress? We now turn to a discussion of the political and economic institutions within which Taiwan’s energy policies are situated.

1.2. Contextualizing Taiwan’s High-Carbon Industrial Structure

Earlier research on the East Asian model of development [20,21,22,23] may be useful for understanding delays in the shift towards cleaner energy and sustainable methods in this area. The East Asian developmental state model asserts that governments in this region have played a direct and influential role in economic development, guiding investment and coordinating with industries to achieve rapid industrialization. This centralized approach has prioritized economic growth over environmental considerations.

Taiwan’s impressive economic transformation into a high-income, industrialized, and export-oriented economy within a relatively short timeframe was largely driven by energy-intensive industries. Over half of Taiwan’s greenhouse gas emissions are attributable to its industrial sector, with key industries such as petrochemicals, electronics, and steel being the most energy-intensive [24,25,26]. Recent studies have described techno-institutional complex ‘lock-ins’ that have emerged in the course of Taiwan’s development [27], observing that Taiwan’s industrial structure was put in place and is still maintained through the interactions between government bureaucracy, industry, and influential private-sector organizations. A key feature of this complex is an array of subsidies and policies that keeps costs for electricity, water, and labor among the lowest in the developed economies, providing critical support in maintaining industrial competitiveness [27,28]. These subsidies disincentivize a transition away from traditional energy consumption practices, as low prices reduce the need for greater efficiency and conservation. This situation creates vested interests among beneficiaries of the current system, who have little reason to deviate from this established, growth-producing strategy [27,29].

In addition to the techno-institutional complex ‘lock-ins’ and the East Asian developmental state model, the global economic situation also plays a significant role in shaping Taiwan’s energy transition. Fluctuations in fossil fuel prices, driven by global supply and demand dynamics, geopolitical events, and economic crises, can impact the incentives for exploring alternative energy sources [30]. During periods of low fossil fuel prices, the economic incentive to transition away from carbon-intensive energy sources may be diminished, as the cost savings from adopting cleaner alternatives are less pronounced. Conversely, when fossil fuel prices are high, the economic case for investing in renewable energy and energy efficiency measures becomes more compelling. However, the volatility of fossil fuel prices can create uncertainty and hesitation among policymakers and investors, as the long-term viability of clean energy projects may be called into question [31]. Thus, in the case of Taiwan, the interplay between global fossil fuel prices and the existing techno-institutional complex further complicates the nation’s energy transition. Recognizing the complex interplay between economic incentives and energy policy, the government faces the difficult task of steering the nation towards a sustainable future. However, the transition to clean energy is hindered by the established ‘techno-institutional complex’, which binds Taiwan’s economic strength to an energy infrastructure dependent on carbon. The collective inertia across all strata of society, from policy architects to industrial leaders, and even among the wider populace, tends to stifle any momentum towards environmentally responsible governance [27,29,32]. These difficulties help explain why Taiwan was the 33rd largest greenhouse gas emitter globally as of 2020, a significant footprint given its population size [15,33].

1.3. Civil Society, Public Opinion, and the Energy Transition in Taiwan

In response to the externalities (e.g., carbon emissions and air, soil and water pollution [27,34] generated by Taiwan’s ‘brown economy’, Taiwan’s civil society responded with environmental activism and protests. To date, however, these movements have been predominantly event-focused and transient [35], resulting in the dissipation of momentum once issues are addressed. This has hindered the formation of a sustained oppositional force [27,32,35]. The outcome is that Taiwan lacks a powerful pro-environmental movement which is a key force shaping public discourse and policy strategies in many Western countries [36,37,38].

Despite the absence of such a movement, however, Taiwanese public opinion has been highly supportive of an energy transition [27], consistently expressing a preference for sustainable energy policies and a willingness to accept the required sacrifices. This is puzzling because the prevailing consensus in existing research, primarily based on findings from Western democracies, suggests a strong correlation between public opinion and the implementation of environmentally friendly policies in democratic societies. Studies [39,40,41] have shown that democracies tend to be responsive to the environmental concerns of their citizens, although other for Europe suggest variations in the strength of this relationship [42]. This trend is particularly evident in the United States [36,43,44] and Europe [45] but has also been found in some international studies [46,47].

One might thus expect Taiwan’s strong public support to be a predictor of both robust organized responses from civil society as well as policies favoring a clean energy transition. Why do we not find such a relationship? A central purpose of this study, then, is to investigate the relationship between public opinion, environmental activism, and political affiliation in Taiwan during the pivotal decade of 2010–2020. It examines public concern for the environment, willingness to make sacrifices for it, and political engagement on these issues. By comparing Taiwan with a subset of developed OECD countries, the study aims to identify unique socio-political factors in Taiwan that deviate from the trend observed in Western democracies.

Then, using social demographic variables, our study investigates the internal dynamics of opinion in Taiwan, starting with income. Research indicates that in many countries, policy outcomes can be heavily influenced by a minority of economic elites, often overriding majority preferences [7,48,49,50]. Given the global trend of higher carbon emissions among the wealthy [51,52,53,54,55]. Taiwan’s affluent, who stand to lose the most from stringent energy policies, may also exercise a disproportionate and negative influence on the clean energy transition, even independently of their role in the ‘techno-institutional complex’ dynamic previously outlined.

In addition to income, our analysis incorporates a range of demographic variables recognized in the literature as significant. These include age, where younger generations often exhibit more concern for the environment, possibly due to a vested interest in the long-term health of the planet [43,56,57]. Gender is also considered, as studies have shown women tend to be slightly more pro-environmental in orientation in Western countries [58,59], whereas in China, research suggests that men may exhibit greater environmental awareness and concern [60]. Educational attainment is included due to its association with environmental awareness and concern [43,61]. Religious beliefs and practices can inform moral and ethical views on stewardship; however, findings on their impact on pro-environmental concern have been mixed in Western countries, with both negative [62,63] and positive [64] findings. Residence type, which affects exposure to environmental issues, was also included. Earlier studies on the impact of residence have shown mixed results [65,66,67]. Our analysis also investigates regional differences, as earlier research has found that the impact of region is significant [68,69]. Lastly, political affiliation is included as a demographic variable due to its established importance in shaping environmental views and policies in Western countries [43,70,71].

To assess the dynamics influencing Taiwan’s energy transition policies, data from the 2010 and 2020 ISSP surveys is used, supplemented by some items from the Taiwan Social Change Survey (TSCS) administered during the same periods. The TSCS largely overlaps in content with the ISSP but has some items specifically created for the Taiwanese context. This period encapsulates a critical juncture in the global energy landscape, marked by the aftermath of the Fukushima disaster and the ramp-up to the Paris Agreement targets. By analyzing data spanning this decade, the evolution of public opinion during a period in which energy policy and sustainability became increasingly salient can be observed.

In short, the demographic variables used in this study enable an in-depth examination of the underlying forces within Taiwan’s civil society shaping public opinion. Additionally, by constructing a cross-country profile of civil society engagement with environmental issues, the study seeks to better understand the causes behind the differences in energy policy outcomes. With a focus on this critical decade, our core research questions seek to further our understanding of obstacles to the energy transition in Taiwan.

Based on the above, this study poses the following research questions: What is the degree of concern, willingness to sacrifice, and level of civic or political engagement on environmental and clean energy issues in Taiwan? How does Taiwan compare on these dimensions with comparable countries internationally?

How has public opinion in Taiwan evolved from 2010 to 2020 on these issues?

What is the socio-demographic profile of supporters of pro-environmental and clean energy policies?

2. Materials and Methods

Participants and Materials

This study utilizes data from the International Social Survey Program [72,73] and Taiwan Social Change Survey [74,75] surveys on the environment administered in 2010 and 2020. These surveys provide comprehensive insight into the public’s perspectives on environmental issues, including attitudes towards energy transition, making it a suitable dataset for our investigation. A majority of the questions in the TSCS are identical to those in the ISSP for the corresponding years, allowing for comparison between Taiwan and other democracies at similar levels of economic development. In particular, 18 OECD countries that took part in the ISSP survey in both 2010 and 2020 are used as a comparison group.

Summary information on the socio-demographic indicators is presented in Table 2. For the income categorization into the bottom 50%, middle 40%, and top 10% of the personal income distribution, the cutoff point separating the bottom 50% from the middle 40% in 2010 and 2020 was located within the range of NT$20,000 to NT$29,999 monthly. The cutoff point separating the middle 40% from the top 10% was within the range of NT 50,000 to NT 59,999 in 2010, and NT 60,000 to NT 69,999 in 2020. (For reference, 1 USD has been worth about NT 30 during the period covered [76]; or NT 15.4, adjusted for purchasing power parity [77]. Thus, for example, as the midpoint value for the income range separating the middle 40% and top 10% was NT 65,000 in 2020, the corresponding amount in PPP-adjusted US dollars would be NT 4220 monthly or NT 50,659 annually. The top 10% of income earners would make about this much or more. Given our stated goal in the Introduction of investigating elite opinion, it is important to acknowledge here that the figures for the ‘elite’—typically understood as the top 1%—would be much higher, and our measure can only serve as a rough proxy for elite sentiment.

Table 2.

Respondent Demographics in Taiwan, ISSP/TSCS 2010 and 2020.

To assess the nature of support for the energy transition, this study analyzes measures related to three dimensions: (1) the degree of concern about the environment and climate change and the salience of the environment as an issue (the ‘salience’ variable is used here as a separate study found it to be the single best predictor of a country’s performance on the Environmental Performance Index [78]; (2) the expressed degree of support for an energy transition and the willingness to sacrifice for environmental protection; (3) political engagement on environmental behaviors. The particular questions used are listed in Table 3, with the variable names used in this study, the questions as they appeared in the survey and their original locations in the surveys.

Table 3.

Opinion Variables from ISSP/TSCS 2010 and 2020.

Below, aggregate levels of concern for Taiwan are compared with the subset of 18 OECD countries that participated in both the 2010 and 2020 administrations of the ISSP survey on the environment: Australia, Austria, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Japan, South Korea, Lithuania, New Zealand, Norway, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the US.

In addition to our descriptive statistics, a series of binary logistic regression was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics, Version 20.

3. Results

Below, descriptive statistics on the variables listed above are provided, comparing levels of concern, willingness to sacrifice and political engagement between Taiwan and our OECD-18 reference group and between the 2010 and 2020 responses. The focus then turns to Taiwan, using binary logistic regressions to identify the relationship between a variety of demographic variables and our environmental concern variables in both 2010 and 2020.

3.1. Descriptive Statistics: 2010 vs. 2020

Taiwan initially exhibited higher levels of general environmental concern in 2010 compared to the OECD reference group (Table 4). However, over the subsequent decade, concern within the OECD nations witnessed a notable increase, whereas Taiwan’s concern levels remained relatively stable. By 2020, the levels of environmental concern in both Taiwan and the OECD reference group had converged. When examining willingness to sacrifice (WTS) for the environment, Taiwan’s levels were either on par with or slightly exceeding OECD levels, even though the latter displayed pronounced increases over the past ten years. However, political engagement related to environmental issues in Taiwan lags far behind that of the OECD comparison group, indicating a divergence in public sentiment and active engagement.

Table 4.

Concern, Willingness to Sacrifice and Engagement on Environmental Issues: Taiwan vs. a Comparison Group of 18 OECD Countries.

An additional ISSP 2010 item asked about the source of energy that the country should prioritize. Table 5 compares Taiwan with the OECD-18 for this variable. A substantial majority of the respondents (83.7%) favor renewable energy sources as the priority for meeting the country’s future energy needs, with only a small fraction (2%) preferring fossil fuels, nuclear (7%) or biofuels (6%). The overwhelming preference for renewable energy suggests a public consciousness leaning towards environmentally sustainable options.

Table 5.

Responses to the question ‘To which of the following should [COUNTRY] give priority in order to meet its future energy needs?’ [72].

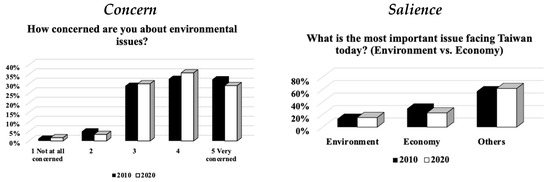

Surprisingly, despite a decade marked by extreme weather, increased media focus, and major policy shifts like the Paris Agreement and SDGs, the distribution of responses on the environmental concern item in 2020 remained at essentially the same (high) levels as in 2010 (Figure 2). The salience of environmental issues has been consistently high and ranked among the top five concerns in Taiwan, alongside education, healthcare, crime, and the economy. However, despite these high levels of concern and salience, economic considerations remained a more pressing priority for the Taiwanese public throughout the 2010–2020 decade (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Concern and Relative Priority/Salience of the Environment as an Issue, 2010 and 2020.

Finally, our findings suggest that climate change denialism is not a significant factor in Taiwan’s slow progress in implementing energy transition policies. The data show that only a small fraction of respondents was unconcerned about environmental issues (Figure 2), with a mere 2.8% advocating for the prioritization of fossil fuel use in Taiwan’s future energy strategy (Table 5).

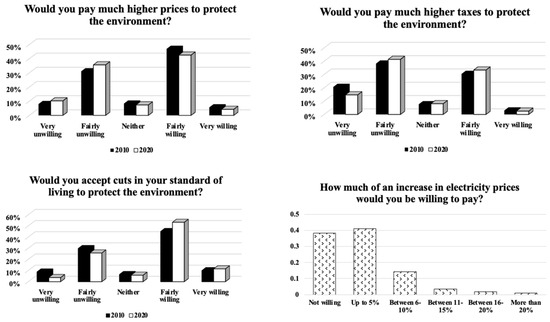

Turning to willingness to sacrifice for the environment, a clear M-shaped distribution (Figure 3) can be observed. This suggests that many respondents who expressed concern were nonetheless unwilling to shoulder the burden required for transformative change. This suggestion is further confirmed by the final distribution, taken from the item on financing the transition (item ‘e6’) [75]: 36.4% of respondents reported being unwilling to accept any increase in electricity prices to reduce emissions, while a total of 79% refused any sacrifice above a 5% increase (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Willingness to Sacrifice for the Environment.

3.2. Binary Logistic Regression Analyses

Table 6 and Table 7 present an analysis of how various socio-demographic factors influence these environmental attitudes in the years 2010 and 2020, respectively.

Starting with the results for 2010 (Table 6), the results show that general concern, age, income, and region are the most highly significant predictors: older people, people with higher incomes, and people outside of the north all expressed higher levels of concern. However, turning to salience (choosing the environment as the first or second most important problem facing Taiwan), education and region are the strongest predictors. More highly educated respondents were more likely to consider the environment as critical. Surprisingly, respondents from the north were also more likely to do so, despite lower levels of general concern.

For preferred future fuel use, no demographic variable stands out as a strong predictor. Given that 81% of all respondents agreed that renewable energy should be the preferred fuel of the future, suggesting a high degree of society-wide consensus on this issue.

For willingness to sacrifice, similar patterns appeared for willingness to pay higher prices and taxes. Higher levels of education and income, along with weekly religious attendance, predict greater willingness. For region, compared to northern respondents, those from central Taiwan are more willing to pay, while those from southern Taiwan are less willing. Surprisingly, the pattern differs for willingness to accept cuts to one’s standard of living. Here, only region is a strong predictor, with southerners less willing. Higher levels of education and weekly religious attendance also predicted greater willingness.

Turning to our four political engagement variables towards the environment, absolute and relative levels of engagement were quite low, with the highest level being 10.8% of respondents reporting making donations in 2010. Less than 2% of the population reported taking part in environmental protests, despite controversies around nuclear power and pollution from coal plants. Regression analyses further support the interpretation that political engagement is generally low across all strata. Higher levels of education and religious attendance (perhaps indicating higher levels of organizational commitment) are the best general predictors, but no strong patterns emerge. Perhaps most striking is that political party affiliation did not significantly predict any of our environmental variables, indicating the lack of politicization of environmental issues at the time of the 2010 survey.

Table 6.

Demographic Predictors of Environmental Attitudes: Logistic Regression Analysis of Taiwan ISSP 2010 Responses.

Table 6.

Demographic Predictors of Environmental Attitudes: Logistic Regression Analysis of Taiwan ISSP 2010 Responses.

| Variable | 2010 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concern | Salience | Fut Fuel | WTS1 | WTS2 | WTS3 | Member | En Ptn | En Don | En Prtst | |

| POLITICAL PARTY (Ref = Pan-Blue) | ||||||||||

| 2 = Pan-Green | ||||||||||

| 3 = Others | ||||||||||

| 4 = Refused | ||||||||||

| SEX (Ref = Male) | 0.78 * | 0.83 | ||||||||

| 2 = Female | 0.46 * | |||||||||

| AGE | 1.02 *** | 1.02 *** | ||||||||

| EDUCATION (Ref = Elem or less) | ||||||||||

| 2 = JHS | 1.16 | 1.24 | 1.22 | 1.22 | 0.88 | 1.36 | 2.43 ** | |||

| 3 = SHS | 1.04 | 1.87 *** | 1.71 *** | 1.82 *** | 1.06 | 1.46 | 1.94 ** | |||

| 4 = University | 1.52 * | 1.95 *** | 2.30 *** | 2.79 *** | 1.42* | 5.37 *** | 2.23 ** | |||

| RELIGION (Ref = None) | ||||||||||

| 1 = Buddhism | 1.29 | 1.95 ** | ||||||||

| 2 = Taoism | 1.26 | 1.4 | ||||||||

| 3 = Folk Religion | 0.82 | 1.16 | ||||||||

| 4 = Yiguan dao | 0.77 | 1.42 | ||||||||

| 5 = Catholicism | 0.08 | 1.11 | ||||||||

| 6 = Protestantism | 0.33 | 0.46 | ||||||||

| 7 = Others | 1.4 | 0.79 | ||||||||

| RELIGIOSITY (Ref = Never) | ||||||||||

| 2 Yearly | 1.25 * | 1.63 | 0.99 | 0.89 | 0.87 | 2.34 *** | 2.05 ** | 1.56 ** | 2.03 | |

| 3 Monthly | 1.75 * | 0.46 | 0.81 | 1.01 | 1.6 * | 4.27 *** | 1.96 | 1.99 * | 3.16 | |

| 4 Weekly | 1.06 | 0.47 | 1.90 ** | 2.08 *** | 1.73 ** | 8.13 *** | 3.13 ** | 2.65 ** | 4.47 ** | |

| RESIDENCE (Ref = Big city) | ||||||||||

| 2 suburbs or outskirts of a big city | 1.231 | |||||||||

| 3 a town or a small city | 1.054 | |||||||||

| 4 a country village or a farm | 0.945 | |||||||||

| INCOME (Ref = Top 10%) | ||||||||||

| 2 Refused to answer | 0.68 | 8,533,623 | 0.34 * | 0.8 | 1.19 | |||||

| 3 Bottom 50% | 0.47 *** | 0.1 * | 0.54 *** | 0.54 *** | 0.65 * | |||||

| 4 Middle 40% | 0.66 * | 0.31 | 0.71 * | 0.61 ** | 0.54 ** | |||||

| REGION (Ref = North) | ||||||||||

| 2 = Centre | 1.54 *** | 0.60 *** | 1.46 ** | 1.3 * | 1.01 | |||||

| 3 = South | 1.32 * | 0.68 *** | 0.88 | 0.67 ** | 0.66 *** | |||||

| 4 = East | 1.29 | 0.71 | 0.99 | 1.08 | 0.84 | |||||

| Nagelkerke | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| X2 | 103.201 | 61.700 | 31.144 | 123.219 | 133.178 | 50.214 | 71.296 | 52.529 | 63.163 | 13.276 |

| P | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.010 |

Notes: * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01, *** p ≤ 0.001.

Turning to the 2020 regression results (Table 7), for general concern, age, religion and religious attendance were the most highly significant predictors: older people, Buddhists and ‘yearly’ attenders all expressed higher levels of concern. Once again, education was the variable most strongly associated with salience. More highly educated respondents were more likely to consider the environment as critical.

For willingness to pay higher prices, higher levels of education, non-rural residents and non-southerners were more willing to accept higher prices. For willingness to pay higher taxes, higher education, non-rural residents, non-southerners and higher income residents were more accepting of higher taxes. Only region predicted a greater willingness to accept cuts to the standard of living, with residents outside of central Taiwan more willing.

Finally, for the willingness to pay higher electricity prices (an item appearing only in 2020), sex, education, religion, urban/rural, income and region were all significantly associated. Once again, the most highly educated were the most willing to pay higher prices. Men, respondents with no stated religion, non-rural respondents, higher-income (Top 10) respondents, and those living in the north were also more willing.

Turning to our four political engagement variables towards the environment, absolute and relative levels of engagement were again quite low, with the highest level being 9.3% of respondents reporting making donations in 2020 and only 1.3% of the population reported taking part in environmental protests, despite controversies around nuclear power and pollution from coal plants. Regression analyses further support the interpretation that political engagement is generally low across all strata. It is difficult to discern any meaningful pattern in terms of the socio-demographic profile of the more politically engaged citizens. Perhaps most striking is that political party affiliation was once again not a strong predictor across all of the different engagement variables, indicating the continued lack of politicization of environmental issues at the time of the 2020 survey.

Table 7.

Demographic Predictors of Environmental Attitudes: Logistic Regression Analysis of Taiwan ISSP 2020 Responses.

Table 7.

Demographic Predictors of Environmental Attitudes: Logistic Regression Analysis of Taiwan ISSP 2020 Responses.

| Variable | 2020 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concern | Salience | WTS1 | WTS2 | WTS3 | En Mbr | En Ptn | e6 BIN | En Don | En Prtst | |

| POLITICAL PARTY (Ref. = Pan-Blue) | ||||||||||

| 2 = Pan-Green | 1.17 | 1.46 * | 1.69 * | 0.72 | 11.47 * | |||||

| 3 = Others | 0.74 * | 0.94 | 1.14 | 0.45 *** | 2.81 | |||||

| 4 = Refused | 0.81 | 0.95 | 1.11 | 0.68 | 2.23 | |||||

| SEX (Ref. = Male) | ||||||||||

| 2 = Female | 1.24 * | 0.66 ** | ||||||||

| AGE | 1.02 *** | 1.01 * | 1.02 * | 0.97 *** | ||||||

| EDUCATION (Ref = Elem or less) | ||||||||||

| 2 = JHS | 1.54 * | 1.62 * | 2.62 *** | 0.42 | 2.83 * | 2.21 | ||||

| 3 = SHS | 1.79 ** | 2.54 *** | 2.99 *** | 2.31 | 3.19 ** | 2.77 * | ||||

| 4 = University | 2.02 *** | 3.33 *** | 3.61 *** | 5.55 ** | 7.59 *** | 5.23 *** | ||||

| RELIGION (Ref = None) | ||||||||||

| 1 = Buddhism | 1.59 ** | 0.71 | ||||||||

| 2 = Taoism | 0.94 | 0.63 * | ||||||||

| 3 = Folk Religion | 0.94 | 0.64 ** | ||||||||

| 4 = Yiguan dao | 0.92 | 0.24 * | ||||||||

| 5 = Catholicism | 4.98 * | 0.33 | ||||||||

| 6 = Protestantism | 2.14 * | 0.36 ** | ||||||||

| 7 = Others | 1.53 | 0.49 | ||||||||

| RELIGIOSITY (Ref = Never) | ||||||||||

| 2 Yearly | 1.62 *** | 2.58 ** | 1.55 * | 2.98 * | ||||||

| 3 Monthly | 1.18 | 1.06 | 1.8 | 0 | ||||||

| 4 Weekly | 1.81 | 9.16 *** | 2.73 ** | 8.58 ** | ||||||

| RESIDENCE (Ref = Big city) | ||||||||||

| 2 suburbs or outskirts of a big city | 0.76 | 0.9 | 0.92 | 0.27 * | 0.54 ** | 0.91 | ||||

| 3 a town or a small city | 1.01 | 0.91 | 0.79 | 1.44 | 0.63 * | 0.85 | ||||

| 4 a country village or a farm | 0.7 * | 0.55 *** | 0.49 *** | 1.84 | 0.36 ** | 0.52 ** | ||||

| INCOME (Ref = Top 10%) | ||||||||||

| 2 Refused to answer | 0.65 | 3.2 | 0.47 * | |||||||

| 3 Bottom 50% | 0.54 ** | 3.27 | 0.41 *** | |||||||

| 4 Middle 40% | 0.61 ** | 2.47 | 0.54 ** | |||||||

| REGION (Ref = North) | ||||||||||

| 2 = Centre | 0.84 | 0.84 | 0.69 ** | 0.48 *** | ||||||

| 3 = South | 0.61 *** | 0.61 *** | 0.75 * | 0.71 * | ||||||

| 4 = East | 0.47 | 0.53 | 1.04 | 0.7 | ||||||

| Nagelkerke | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.11 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.06 | 0.12 |

| X2 | 124.086 | 16.637 | 131.789 | 138.371 | 21.171 | 67.979 | 155.172 | 248.494 | 43.172 | 25.258 |

| P | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

Notes: * p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01, *** p ≤ 0.001.

Comparing results from 2010 and 2020, a small number of patterns were stable across the decade. Certain demographic factors such as age and education consistently predict environmental concern and salience in Taiwan. Willingness to sacrifice financially for environmental benefits has seen shifts, with only income and education continuing to play a role. Political engagement towards environmental issues remains strikingly low, with no significant shift over the years, underscoring a persistent non-politicization of the environment.

4. Discussion

The pivotal decade from 2010 to 2020 was marked by significant environmental and policy milestones. It began with the Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011, highlighting the complexities of energy policy. This was followed by extreme weather events, including Hurricane Sandy and Typhoon Haiyan, emphasizing the urgency for climate action. The signing of the Paris Agreement and the introduction of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015 were key responses to these challenges, reflecting a global commitment to environmental sustainability. Building on the global environmental and policy shifts from 2010 to 2020, this study used ISSP and TSCS survey data to explore how these changes affected Taiwan’s public opinion, contrasting it with the broader international response.

Although Taiwanese concern for the environment was notably high in 2010, it changed little over the decade. Further, Taiwan’s high level of concern did not translate into an increased willingness to incur higher costs for sustainable energy solutions. This contrasts with the OECD countries, where environmental concern started at a lower level but saw a substantial increase, and where there was substantial acceptance of the need for financial sacrifices.

In terms of social demographic predictors, age and education emerge as stable predictors of environmental concern, with older and more highly educated respondents showing higher concern. Showing a willingness to make financial sacrifices was only predicted by higher levels of income and education. Surprisingly, political party affiliation was not associated with differences of opinion or engagement. A sharp contrast to findings from the OECD group was the comparatively low level of civil society engagement in environmental politics in Taiwan, evidenced across both survey years. This lack of political engagement around environmental and energy policy issues marks a distinct pattern characterizing the policy development process in Taiwan.

4.1. Income and Environmental Engagement

Earlier studies showed broad support for environmental protection and the energy transition from surveys in 2012 and 2015 [79,80]. Further, a 2018 Greenpeace survey found that when the purpose of increased electricity rates is explained to the public, willingness to make financial sacrifices is as high as 71.2% [80]. These findings are at odds with our own. The present study found that lower income earners are less concerned about the environment and especially less willing to make sacrifices. This income-based difference may also explain the broader pattern in which clear declines in support are observed when particular material sacrifices are specified—cuts in living standards, higher prices, and higher taxes (Figure 2 and Figure 3 above). Thus, whereas an earlier study [80] saw a slight but steady decline in levels of willingness to accept sacrifices, this study found a clear M-shaped distribution (Figure 3), suggesting a split in the population, likely based on income (Table 5 and Table 6). Further, when respondents were asked to specify the increase in electricity prices they were willing to pay, the drop in support was even sharper (Figure 3 above).

Our findings may be interpreted through the lens of Taiwan’s economic model, as discussed in the introduction. This model is characterized by a socio-economic contract where the government maintains low wages to ensure a competitive export economy, while simultaneously balancing this with subsidized utility costs [27,28] to alleviate financial burdens on the populace. We suggest that the reluctance of the lower income bracket in Taiwan to support financial sacrifices for environmental protection can be seen as a direct consequence of this socio-economic arrangement. Recall that the income threshold dividing the bottom 50% and the middle 40% ranged from US$667 to $1000 per month, an amount that did not change between the 2010 and 2020 surveys (using purchasing power parity adjustments, these figures would be US$1300 to $1950; [76,77]).

Further, recent trends show a sharp decline in national income shares for lower-income groups, with the share of the middle 40%’s falling from about 50% to just over 40%, and the bottom 50%’s share dropping from over 20% in the 1980s to just above 10% by 2020 [81].context, it is not surprising that any rise in utility costs is met with reluctance or opposition. Our analysis thus suggests that in Taiwan, the willingness to make environmental sacrifices is intricately tied to this implicit social contract. In this context, while the government has a clear incentive to maintain productivity and growth by accommodating industry actions, there is little incentive for politicians to endorse an energy transition program that would substantially raise utility prices.

4.2. Political Engagement and Energy Policy

In addressing the paradox between high levels of environmental concern and low levels of political engagement in Taiwan, it is crucial to consider the structural and historical constraints on civil society’s influence over national policy-making. As detailed by a number of previous authors [27,32,34], Taiwan’s political and economic development has historically been dominated by a developmental state framework, which prioritizes economic growth often at the expense of environmental considerations. This framework has not only marginalized civil society’s role in policy discourse but has also entrenched interests that resist transformative environmental policies [32].

The limitations of civil society efforts in relation to national policymaking have also been highlighted, with an earlier study noting that while there are active environmental movements, they are often fragmented and lack the political leverage to effectuate systemic environmental reforms within Taiwan’s entrenched high-carbon economic framework [32]. Similarly, one study of the politics surrounding efforts to implement a carbon tax in Taiwan [27] found that despite the occurrence of various social movements since the mid-1980s, these movements have not been able to sustain long-term pressure on the government to implement systemic changes. This led to efforts at reforms being carried out within the existing bureaucratic structure, where civil society efforts have had difficulty prevailing given the current balance of power in favor of ‘brown economy’ interests [35].

This difficulty in forming a sustained grassroots movement in Taiwan is in sharp contrast with politics in the West, where environmental issues are not only politicized but also often form a core part of political identity [36,38,82]. In Taiwan, political engagement in environmental issues is comparatively quite low, even in the face of pressing environmental concerns such as the role of nuclear energy and fossil fuel use. This divergence is not just limited to activism; our findings show that, unlike Western countries [83], political party affiliations in Taiwan are not strongly linked to environmental attitudes or actions. Indeed, the number of respondents who declared affiliation with the Green Party was exceptionally low: none out of 2210 respondents in 2010; seven out of 1822 in 2020.

Furthermore, Taiwan is likely to be representative of other East Asian countries like South Korea, Japan, and, to some extent, China. In all of these countries, there is a lack of strong politicization around environmental and energy transition issues [84], with South Korea being a partial exception. This could indicate a regional pattern in which environmental and energy policy does not significantly intersect with political partisanship or activism, differing starkly from Western models. These nations share similar economic trajectories, characterized primarily by export-oriented economies, as well as control by bureaucracies that remain largely insulated from political pressures and public opinion [84].

4.3. An East Asian Model of Energy Policy Formation?

This suggests the continued relevance of the earlier literature on the East Asian developmental state to grasp the nature of the transition towards cleaner energy and sustainable practices in this region. Chalmers Johnson contrasted the different relations between the government and the private sector in what he labeled ‘regulatory’ and ‘developmental’ states [21]. European and North American ‘regulatory states’ are more ‘external’ to the economy and govern largely through enforcing regulations and standards to protect the public against various types of market failures, such as monopolistic pricing, predation, or environmental damage, and by providing collective goods (e.g., health, education, defense). In contrast, in some late-industrializing countries such as the ‘dragon’ economies of East Asia, the state and the private sector are more tightly integrated, and the state itself takes a direct and leading role in promoting economic development.

This, we argue, has implications for understanding the role of public opinion. In ‘regulatory states’, such as the US, the conflict between economic interests and the environment is played out in the political sphere. In terms of climate change, for example, vested economic interests have funded efforts to capture or block the regulatory agencies that threaten to impose limitations on carbon emissions. Part of this strategy has included spreading doubt about climate change [85]. As a result, pro-environmental policy makers and activists have been put on the defensive and forced to focus on persuading the public, wasting vital time. In East Asia, by contrast, public opinion is often disregarded in policy making, and the conflict between industrial lobbies and the environment occurs through inter-ministerial disputes within governments. For these reasons, private-sector disinformation campaigns are unnecessary. In addition to this dynamic, prices and salaries have been kept comparatively low in some developmental states, including Taiwan, to maintain export competitiveness. This adds a further obstacle to mobilizing support in the face of higher potential costs associated with a clean energy transition. Taken together, these factors would help explain the presence, in East Asian countries, of populations knowledgeable and concerned about climate change [60] but economies still locked into dangerously high levels of emissions. Given the importance of East Asia to the global environment, future research should focus on the dynamics of public opinion and civil society engagement in the region, without assuming similarity to patterns in Western countries.

4.4. Limitations

The study’s insights into public opinion trends on environmental issues in Taiwan versus OECD countries come with limitations. With only two surveys, a decade apart, it is challenging to form a comprehensive picture of historical trends or subtle shifts in public attitudes. The ten-year interval may overlook nuanced changes, especially considering the potential impact of global events like the 2008 financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic on the 2010 and 2020 data points, respectively.

Another limitation lies in our assessment of the opinions of economic ‘elites’. Our measure only captures the average views of the top 10% of income earners, whereas a better measure of elites would focus on the top 1%. Unfortunately, the size of our samples did not permit conclusions about this smaller group, leaving it an important issue for future research given their outsized role in generating greenhouse gas emissions [51,52,53,54,55].

Finally, survey inconsistencies, including question relevance and presence across both surveys, limit the study’s depth. Moreover, the translation of survey items might have introduced additional variability, affecting response accuracy and comparability over time.

Despite these constraints, the study offers a snapshot of public opinion during a decade marked by significant economic and health crises, providing valuable insights into the public’s environmental stance during this period.

5. Conclusions

Taiwan’s experience highlights the unique dynamics in East Asian nations, where environmental issues are less politicized compared to Western models, pointing towards a need for region-specific policy frameworks. Understanding this context is crucial, as East Asia plays a pivotal role in the global environmental landscape due to its significant industrial output and emissions levels. Our study underscores the importance of acknowledging these socio-political differences when considering environmental policies in East Asian countries.

In light of Taiwan’s growing income inequality [81] and the reluctance of lower-income groups to support environmental transitions, our policy recommendations focus on fostering a ‘just’ energy transition, aligning with Sustainable Development Goal 7 (SDG 7). Given Taiwan’s domestic situation and export-oriented economic model, it may be that a ‘just’ transition would also be a more politically feasible strategy [86]. A transition strategy that is ‘just’ and equitable, acknowledging the disparities in income and willingness to sacrifice, might be a pragmatic approach to ensure broader acceptance and success of Taiwan’s energy transition policies. This is in line with the more general principle, emphasized by [87], that tailoring policies for a diverse set of stakeholders is likely to enhance the feasibility of energy transition strategies.

Finally, given the historical and cultural specifics of Taiwan’s development and the observed low political engagement in environmental issues, optimism for internal change should be tempered. A potential catalyst for policy evolution could come from external pressures, such as EU carbon border adjustments and international standards like the SDGs, which might nudge Taiwan, and its East Asian neighbors, towards aligning with global environmental norms and commitments. Notably, changes in Taiwan’s environmental policies to date appear to have been significantly influenced by responses to external pressures from corporate customers, foreign governments, and international agreements [32,88].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.D.G., J.L., I.Ž. and Y.H.D.G.; Methodology, B.D.G. and J.L.; Formal Analysis, B.D.G. and J.L.; Data Curation, I.Ž.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, B.D.G. and J.L.; Writing—Review & Editing, B.D.G., J.L., I.Ž. and Y.H.D.G.; Funding Acquisition, B.D.G. and J.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Taiwan’s National Science and Technology Council (NSTC-112-2410-H-130-040-) and a Ming Chuan University internal research subsidy.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data is publicly available at the International Social Survey Program and Taiwan Social Change Survey websites.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Fernandes-Jesus, M.; Brendon, B.; Diniz, R.F. Communities reclaiming power and social justice in the face of climate change. Community Psychol. Glob. Perspect. 2020, 6, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Mehrabi, Z.; Delzeit, R.; Ignaciuk, A.; Levers, C.; Braich, G.; Bajaj, K.; You, L. Research priorities for global food security under extreme events. One Earth 2022, 5, 756–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pörtner, H.O.; Roberts, D.C.; Adams, H.; Adler, C.; Aldunce, P.; Ali, E.; Birkmann, J. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability; IPCC Sixth Assessment Report; IPCC: Paris, France, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations/Framework Convention on Climate Change; Bell, E.; Cullen, J.; Taylor, S. Adoption of the Paris Agreement. In Proceedings of the 21st Conference of the Parties, Paris, France, 30 November–13 December 2015; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UNGA [United Nations General Assembly]. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (A/RES/70/1). 2015. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf (accessed on 31 October 2023).

- Rosenbloom, D.; Markard, J.; Geels, F.W.; Fuenfschilling, L. Why carbon pricing is not sufficient to mitigate climate change—And how “sustainability transition policy” can help. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 8664–8668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoddard, I.; Anderson, K.; Capstick, S.; Carton, W.; Depledge, J.; Facer, K.; Williams, M. Three Decades of Climate Mitigation: Why Haven’t We Bent the Global Emissions Curve? Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2021, 46, 653–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- York, R.; Bell, S.E. Energy transitions or additions?: Why a transition from fossil fuels requires more than the growth of renewable energy. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2019, 51, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Giusto, B.; Lavallee, J.P.; Yu, T.Y. Towards an East Asian model of climate change awareness: A questionnaire study among university students in Taiwan. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0206298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drews, S.; Bergh, J.C. What explains public support for climate policies? A review of empirical and experimental studies. Clim. Policy 2016, 16, 855–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burck, J.; Bals, C.; Parker, L. Climate Change Performance Index 2010; Germanwatch: Bonn, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Burck, J.; Hagen, U.; Hohne, N.; Nascimento, L.; Bals, C. Climate Change Performance Index 2020; Germanwatch: Bonn, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Friedlingstein, P.; O’Sullivan, M.; Jones, M.W.; Andrew, R.M.; Gregor, L.; Hauck, J.; Le Quéré, C.; Luijkx, I.T.; Olsen, A.; Peters, G.P.; et al. Global Carbon Budget 2022. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2022, 14, 4811–4900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NDC [National Development Council]. (n.d.). Taiwan’s Pathway to Net-Zero Emissions in 2050. Available online: https://www.ndc.gov.tw/en/Content_List.aspx?n=B154724D802DC488 (accessed on 10 November 2023).

- BoE/MoEA [Bureau of Energy, Ministry of Economic Affairs]. Energy Statistics Handbook 2021; Bureau of Energy, Ministry of Economic Affairs: Taipei, Taiwan, 2022.

- Germanwatch. Chinese Taipei—Climate Performance Ranking 2023. In Climate Change Performance Index; Germanwatch: Bonn, Germany, 2023; Available online: https://ccpi.org/country/twn/ (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Burck, J.; Uhlich, T.; Bals, C.; Höhne, N.; Nascimento, L. Climate Change Performance Index 2024; Germanwatch: Bonn, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- BoE/MoEA [Bureau of Energy, Ministry of Economic Affairs]. Energy Statistics Handbook 2022; Bureau of Energy, Ministry of Economic Affairs: Taipei, Taiwan, 2023.

- Chuang, M. Economic Affairs Minister: “We Now (Estimate) That Renewable Energy Will Account for Only 15 Percent by the End of 2025”. PTS News. 2022. Available online: https://news.pts.org.tw/article/561764 (accessed on 15 November 2023).

- Amsden, A.H. Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C. MITI and the Japanese Miracle: The Growth of Industrial Policy, 1925–1975; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Wade, R. Governing the Market: Economic Theory and the Role of Government in East Asian Industrialization; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Wade, R.H. The developmental state: Dead or alive? Dev. Change 2018, 49, 518–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, P. Taiwan’s Energy (In) Security: Challenges to Growth and Development. Jadavpur J. Int. Relat. 2022, 26, 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, K.T.; Walther, D.; Liou, H.M. The conundrums of sustainability: Carbon emissions and electricity consumption in the electronics and petrochemical industries in Taiwan. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferry, T. Taiwan’s Energy Dilemma: Emission Reductions vs. Dwindling Supply. Taiwan Business Topics. 2015. Available online: https://topics.amcham.com.tw/2015/09/carbon-abatement-and-energy-supply/ (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Chou, K.T.; Liou, H.M. Carbon tax in Taiwan: Path dependence and the high-carbon regime. Energies 2023, 16, 513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-L. An overview of energy policy and usage in Taiwan. In Asia Program Special Report No. 146: Taiwan’s Energy Conundrum; Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.C.L.; Chen, R.Y. Uncovering regime resistance in energy transition: Role of electricity iron triangle in Taiwan. Environ. Policy Gov. 2021, 31, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. World Energy Outlook 2021, IEA, Paris. 2021. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/world-energy-outlook-2021 (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Balcilar, M.; Roubaud, D.; Shahbaz, M. The impact of energy market uncertainty shocks on energy transition in Europe. Energy J. 2019, 40 (Suppl. S1), 55–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.C.-E.; Chao, C.W. Politics of climate change mitigation in Taiwan: International isolation, developmentalism legacy, and civil society responses. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change 2023, 14, e834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WRI [World Resources Institute]. (n.d.). Greenhouse Gas (GHG) Emissions. Available online: https://www.climatewatchdata.org/ghg-emissions?end_year=2020&start_year=1990 (accessed on 30 January 2024).

- Chan, D.C. The environmental dilemma in Taiwan. J. Northeast Asian Stud. 1993, 12, 35–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grano, S.A. Change and continuities: Taiwan’s post-2008 environmental policies. J. Curr. Chin. Aff. 2014, 43, 129–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnone, J. Amplifying public opinion: The policy impact of the US environmental movement. Soc. Forces 2007, 85, 1593–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, L.M.; Bernauer, T. Explaining government choices for promoting renewable energy. Energy Policy 2014, 68, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, L.M.; Oehl, B.; Bernauer, T. Are policymakers responsive to public demand in climate politics? J. Public Policy 2022, 42, 136–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bättig, M.B.; Bernauer, T. National institutions and global public goods: Are democracies more cooperative in climate change policy? Int. Organ. 2009, 63, 281–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorino, D.J. Environmental policy as learning: A new view of an old landscape. Public Adm. Rev. 2001, 61, 322–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumayer, E. Do democracies exhibit stronger international environmental commitment? A cross-country analysis. J. Peace Res. 2002, 39, 139–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwerdtle, P.N.; Cavan, E.; Pilz, L.; Oggioni, S.D.; Crosta, A.; Kaleyeva, V.; Jungmann, M. Interlinkages between Climate Change Impacts, Public Attitudes, and Climate Action—Exploring Trends before and after the Paris Agreement in the EU. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.E.; Dunlap, R.E. The Social Bases of Environmental Concern: Have They Changed Over Time? Rural. Sociol. 2010, 57, 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandeweerdt, C.B.K.; Cohn, A. Climate voting in the US congress: The power of public concern. Environ. Polit. 2016, 25, 268–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.; Böhmelt, T.; Ward, H. Public opinion and environmental policy output: A cross-national analysis of energy policies in Europe. Environ. Res. Lett. 2017, 12, 114011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjernström, E.; Tietenberg, T. Do differences in attitudes explain differences in national climate change policies? Ecol. Econ. 2008, 65, 315–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, A.A. Does Protest Behavior Mediate the Effects of Public Opinion on National Environmental Policies? A Simple Question and a Complex Answer. Int. J. Sociol. 2008, 38, 108–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, W.M. Poor and powerless: Economic and political inequality in cross-national perspective, 1981–2011. Int. Sociol. 2018, 33, 357–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilens, M.; Page, B.I. Testing theories of American politics: Elites, interest groups, and average citizens. Perspect. Politics 2014, 12, 564–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.; Dubrow, J.K. Politics and Inequality in Comparative Perspective: A Research Agenda. Am. Behav. Sci. 2020, 64, 1199–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adua, L. Super polluters and carbon emissions: Spotlighting how higher-income and wealthier households disproportionately despoil our atmospheric commons. Energy Policy 2022, 162, 112768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chancel, L. Global carbon inequality over 1990–2019. Nat. Sustain. 2022, 5, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chancel, L.; Piketty, T.; Saez, E.; Zucman, G. World Inequality Report; World Inequality Lab: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kenner, D. Carbon Inequality: The Role of the Richest in Climate Change; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wiedmann, T.; Lenzen, M.; Keyßer, L.T.; Steinberger, J.K. Scientists’ warning on affluence. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernauer, T. Climate change politics. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 2013, 16, 421–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R. Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Society; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- McCright, A.M.; Xiao, C. Gender and environmental concern: Insights from recent work and for future research. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2014, 27, 1109–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; McCright, A.M. Explaining gender differences in concern about environmental problems in the United States. Soc. Nat. Resour. 2012, 25, 1067–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.C.-E. Public opinion on climate change in China—Evidence from two national surveys. PloS Clim. 2023, 2, e0000065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Saijo, T. Reexamining the relations between socio-demographic characteristics and individual environmental concern: Evidence from Shanghai data. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, M.B.; Konisky, D.M. The role of religion in environmental attitudes. Soc. Sci. Q. 2015, 96, 1244–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arli, D.; van Esch, P.; Cui, Y. Who cares more about the environment, those with an intrinsic, an extrinsic, a quest, or an atheistic religious orientation?: Investigating the effect of religious ad appeals on attitudes toward the environment. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 185, 427–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodrum, E.; Wolkomir, M.J. Religious effects on environmentalism. Sociol. Spectr. 1997, 17, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Peterson, M.N.; Hull, V.; Lu, C.; Lee, G.D.; Hong, D.; Liu, J. Effects of attitudinal and sociodemographic factors on pro-environmental behaviour in urban China. Environ. Conserv. 2011, 38, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: A review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huddart-Kennedy, E.; Beckley, T.M.; McFarlane, B.L.; Nadeau, S. Rural-urban differences in environmental concern in Canada. Rural. Sociol. 2009, 74, 309–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquart-Pyatt, S.T. Environmental concerns in cross-national context: How do mass publics in central and eastern Europe compare with other regions of the world? Sociol. Časopis/Czech Sociol. Rev. 2012, 48, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquart-Pyatt, S.T. Contextual influences on environmental concerns cross-nationally: A multilevel investigation. Soc. Sci. Res. 2012, 41, 1085–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCright, A.M. Political orientation moderates Americans’ beliefs and concern about climate change. Clim. Change 2011, 104, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; DeCillia, B.; Santos, J.B.; Thorlakson, L. Great expectations: Public opinion about energy transition. Energy Policy 2022, 162, 112777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISSP Research Group. International Social Survey Programme (ISSP): Environment III; GESIS Cologne Germany: Cologne, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- ISSP Research Group. International Social Survey Programme: Environment IV—ISSP 2020; ZA7650 Data file Version 1.0.0; GESIS: Cologne, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Academia Sinica. Taiwan Social Change Survey, Survey on the Environment. 2010. Available online: https://www2.ios.sinica.edu.tw/sc/cht/scDownload3a.php#sixth (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- Academia Sinica. Taiwan Social Change Survey, Survey on the Environment. 2020. Available online: https://www2.ios.sinica.edu.tw/sc/cht/scDownload3a.php#eighth (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- XE. (n.d.). USD to TWD Currency Chart. Available online: https://www.xe.com/currencycharts/?from=USDandto=TWDandview=10Y (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- IMF [International Monetary Fund.] (n.d.). DataMapper: Purchasing Power Parities (PPP) Exchange Rate. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/PPPEX@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD/TWN (accessed on 7 January 2024).

- Lavallee, J.P.; Di Giusto, B.; Yu, T.Y.; Hung, S.P. Reliability and Validity of Widely Used International Surveys on the Environment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, K.T. Sociology of Climate Change: High Carbon Society and Its Transformation Challenge; National Taiwan University Press: Taipei, Taiwan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, K.-T.; Liou, H.-M. Climate change governance in Taiwan: The transitional gridlock by a high-carbon regime. In Climate Change Governance in Asia; Chou, K.T., Hasegawa, K., Ku, D., Kao, S.F., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2020; Chapter 3. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, Z. Is East Asia Becoming Plutocratic? Income and Wealth Inequalities in Mainland China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan (1981–2021) (Issue Brief No. 2022-11). World Inequality Lab. 2022. Available online: https://wid.world/document/is-east-asia-becoming-plutocratic-world-inequality-lab-issue-brief-2022-05/ (accessed on 30 November 2023).

- McCright, A.M.; Dunlap, R.E. Cool dudes: The denial of climate change among conservative white males in the United States. Glob. Environ. Change 2011, 21, 1163–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gethin, A.; Martínez-Toledano, C.; Piketty, T. (Eds.) Political Cleavages and Social Inequalities: A Study of Fifty Democracies, 1948–2020; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, K.T. (Ed.) Energy Transition in East Asia: A Social Science Perspective; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Muffett, C.; Feit, S. Smoke and Fumes: The Legal and Evidentiary Basis for Holding Big Oil Accountable for the Climate Crisis; The Center for International Environmental Law: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, M.Z.; Yeh, T.K.; Chen, J.-S. An unjust and failed energy transition strategy? Taiwan’s goal of becoming nuclear-free by 2025. Energy Strategy Rev. 2022, 44, 100991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Y. Exploring the Key Factors Influencing Sustainable Urban Renewal from the Perspective of Multiple Stakeholders. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyu, C.-W. Development of Taiwanese government’s climate policy after the Kyoto protocol: Applying policy network theory as an analytical framework. Energy Policy 2014, 69, 334–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).