Detection of Ascorbic Acid by Two-Dimensional Conductive Metal-Organic Framework-Based Electrochemical Sensors

Abstract

:1. Introduction

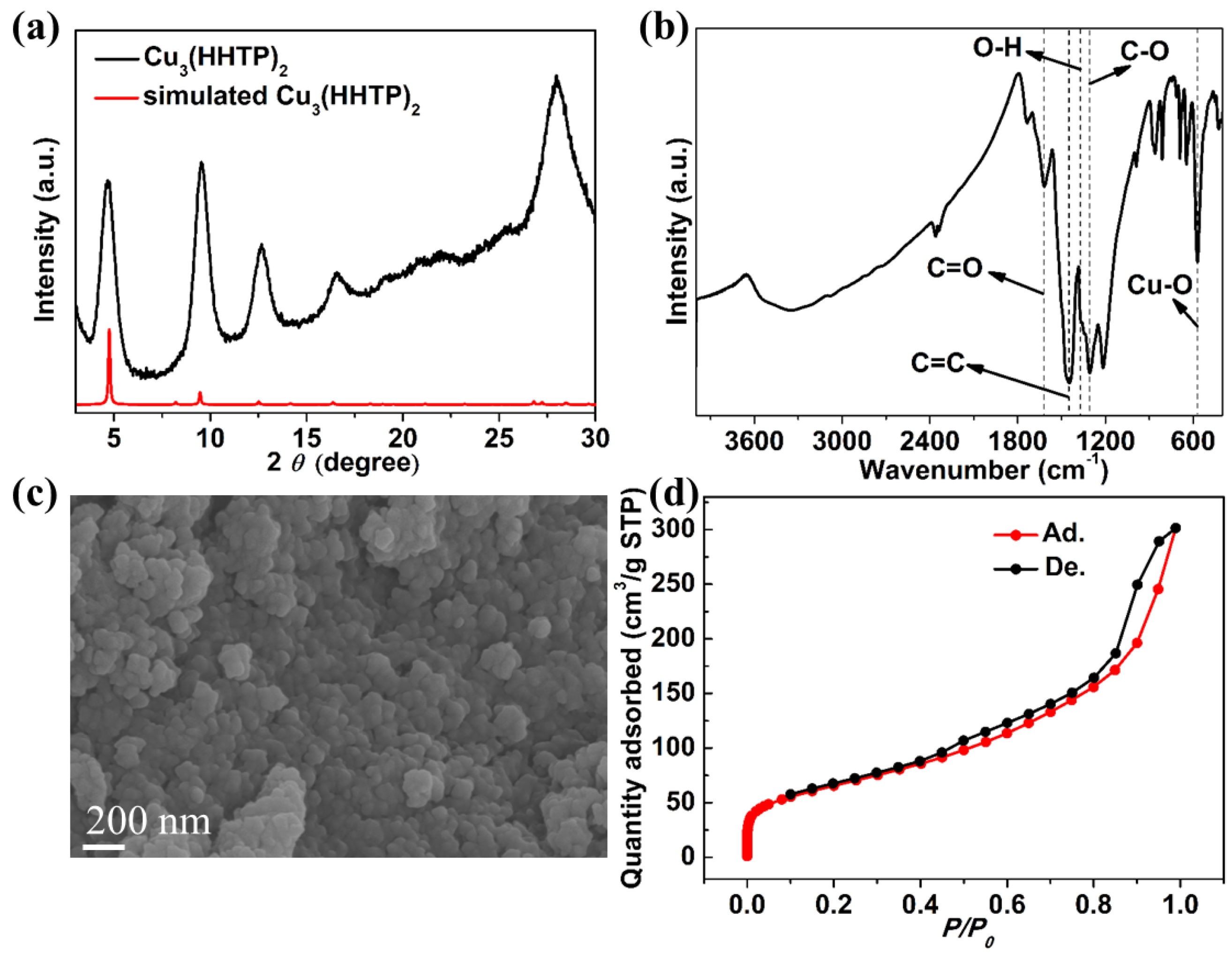

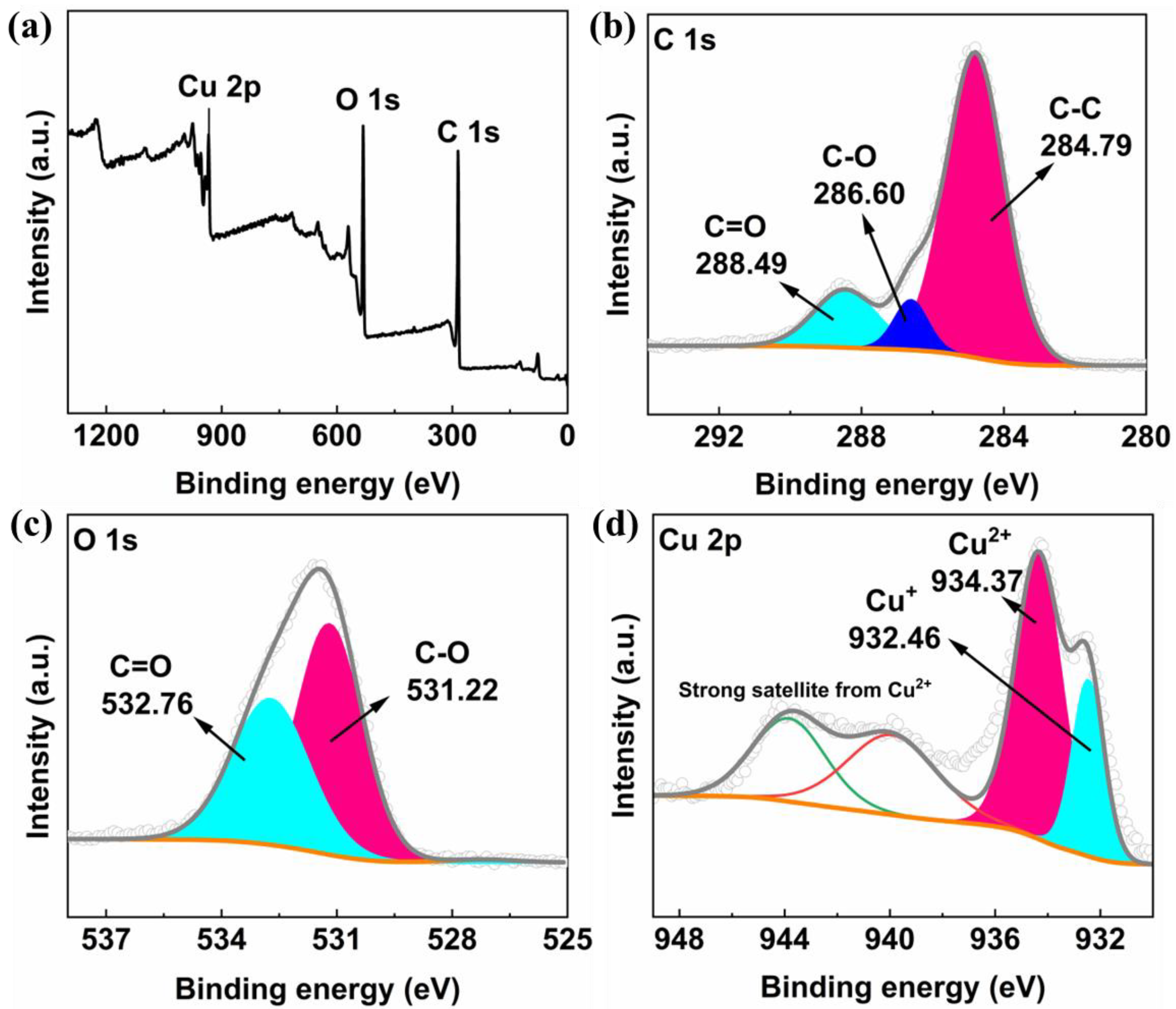

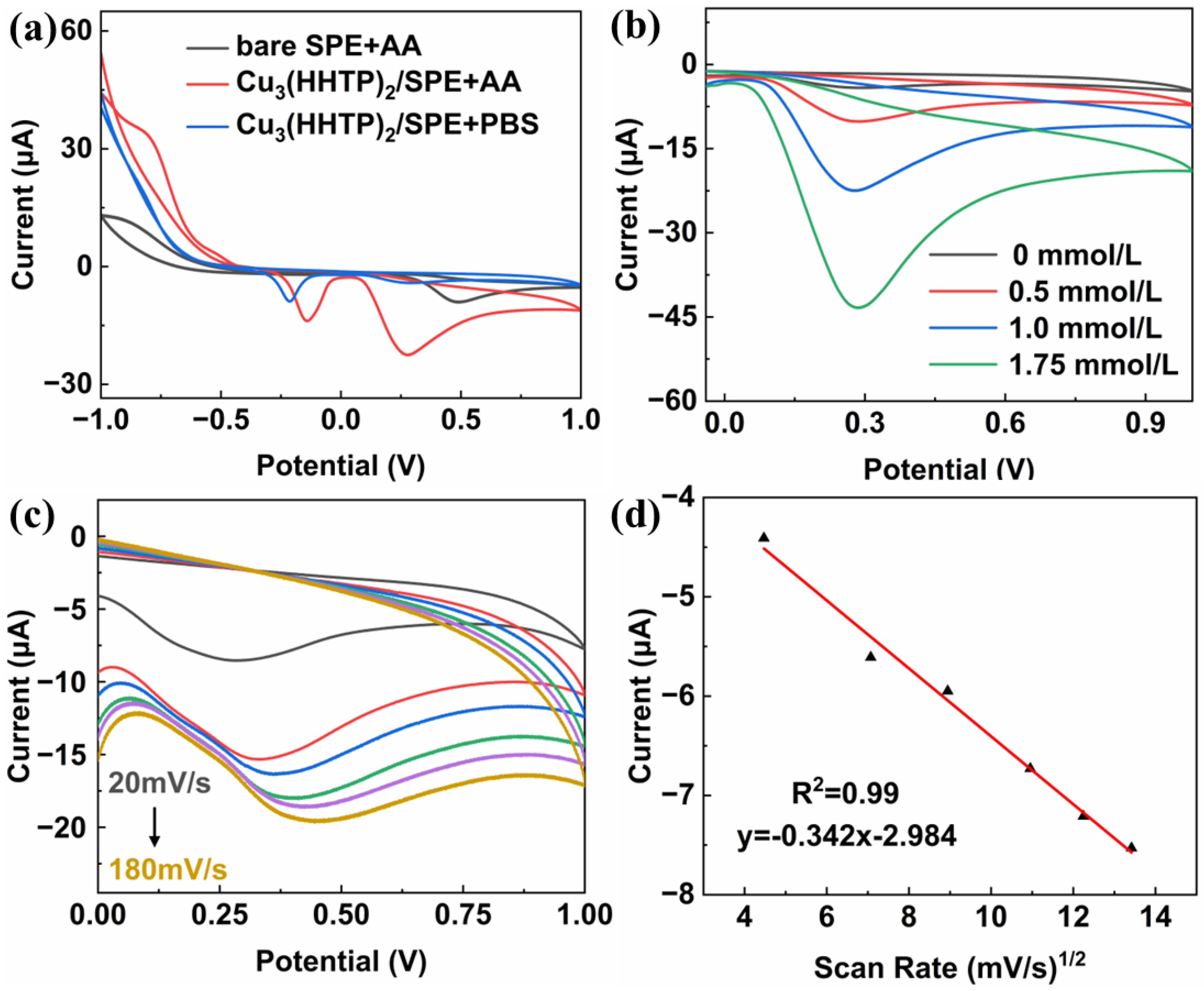

2. Results and Discussion

3. Experiment

3.1. Instruments and Reagents

3.2. Experimental Methods

3.2.1. Electrode Pretreatment

3.2.2. The Synthesis of Cu3(HHTP)2

3.2.3. The Preparation of Cu3(HHTP)2/SPE

3.2.4. Electrochemical Test

3.2.5. Calculation of Electrochemically Surface Area (ESA)

3.2.6. Electrode Uncertainty Experiments

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liang, X.-H.; Yu, A.-X.; Bo, X.-J.; Du, D.-Y.; Su, Z.-M. Metal/covalent-organic frameworks-based electrochemical sensors for the detection of ascorbic acid, dopamine and uric acid. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2023, 497, 215427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reang, J.; Sharma, P.C.; Thakur, V.K.; Majeed, J. Understanding the Therapeutic Potential of Ascorbic Acid in the Battle to Overcome Cancer. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pizzicannella, J.; Marconi, G.D.; Guarnieri, S.; Fonticoli, L.; Della Rocca, Y.; Konstantinidou, F.; Rajan, T.S.; Gatta, V.; Trubiani, O.; Diomede, F. Role of ascorbic acid in the regulation of epigenetic processes induced by Porphyromonas gingivalis in endothelial-committed oral stem cells. Histochem. Cell Biol. 2021, 156, 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, L.-L.; Wu, Y.-X.; Zhang, D.-L.; Hu, X.-X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, P.; Song, Z.-L.; Zhang, X.-B.; Tan, W. Near Infrared Graphene Quantum Dots-Based Two-Photon Nanoprobe for Direct Bioimaging of Endogenous Ascorbic Acid in Living Cells. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 4077–4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Yue, G.; Huang, J.; Liu, C.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, L. Label-Free Simultaneous Analysis of Fe(III) and Ascorbic Acid Using Fluorescence Switching of Ultrathin Graphitic Carbon Nitride Nanosheets. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 26118–26127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, G.; Ge, L.; Li, Y.; Mukhtar, M.; Shen, B.; Yang, D.; Li, J. Carbon dots derived from flax straw for highly sensitive and selective detections of cobalt, chromium, and ascorbic acid. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 579, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motsaathebe, P.C.; Fayemi, O.E. Electrochemical Detection of Ascorbic Acid in Oranges at MWCNT-AONP Nanocomposite Fabricated Electrode. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dodevska, T.; Hadzhiev, D.; Shterev, I. A Review on Electrochemical Microsensors for Ascorbic Acid Detection: Clinical, Pharmaceutical, and Food Safety Applications. Micromachines 2023, 14, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Argoubi, W.; Rabti, A.; Ben Aoun, S.; Raouafi, N. Sensitive detection of ascorbic acid using screen-printed electrodes modified by electroactive melanin-like nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 37384–37390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.P.; Huang, L.; Zhang, J.; Chu, X.F.; Zhang, Q.F. Electro-oxidation of ascorbic acid at bismuth sulfide nanorod modified glassy carbon electrode. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 74, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatamie, A.; Rahmati, R.; Rezvani, E.; Angizi, S.; Simchi, A. Yttrium Hexacyanoferrate Microflowers on Freestanding Three-Dimensional Graphene Substrates for Ascorbic Acid Detection. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2019, 2, 2212–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvin, E.A.; de Moraes, N.C.; de Oliveira, Y.M.; da Silva, D.G.P.; Barbosa, A.I.D.S.; Ribeiro, W.S.M.; Vermelho, M.V.D.; de Freitas, J.M.D.; de Freitas, J.D.; Dantas, N.O.; et al. A novel paper-based electrochemical device modified with Ni-doped TiO2 nanocrystals-decorated graphene oxide for ascorbic acid detection. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2024, 314, 128786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Xie, L.; Yan, F.; Liang, Z.; Liang, J.; Huang, K.; Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Luo, L.; Li, T.; et al. A novel electrochemical aptasensor based on polyaniline and gold nanoparticles for ultrasensitive and selective detection of ascorbic acid. Anal. Methods 2023, 15, 4010–4020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzara, F.; Patella, B.; Aiello, G.; O’Riordan, A.; Torino, C.; Vilasi, A.; Inguanta, R. Electrochemical detection of uric acid and ascorbic acid using r-GO/NPs based sensors. Electrochim. Acta 2021, 388, 138652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, D.; Liu, H.; Chen, T.; Cheng, Y.; Cao, M.; Liu, J. A bio-analytic nanoplatform based on Au post-functionalized CeFeO3 for the simultaneous determination of melatonin and ascorbic acid through photo-assisted electrochemical technology. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 213, 114457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geleta, G.S. Recent advances in electrochemical sensors based on molecularly imprinted polymers and nanomaterials for detection of ascorbic acid, dopamine, and uric acid: A review. Sens. Bio-Sens. Res. 2024, 43, 100610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, P.; Huang, J.; Lin, L.; Li, R.; Tang, M.; Wang, Z. Zirconium-based metal-organic Framework as an Efficiently Heterogeneous Photocatalyst for Oxidation of Benzyl Halides to Aldehydes. Mol. Catal. 2021, 506, 111542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Fang, S.; Xue, P.; Huang, J.; Tang, M.; Wang, Z. Reversible Regulation of Polar Gas Molecules by Azobenzene-Based Photoswitchable Metal-Organic Framework Thin Films. Molecules 2023, 28, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Fan, K.; Gu, Y.; Sun, M.; Li, Z.; Zhang, C.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Xu, S.; et al. Successive Storage of Cations and Anions by Ligands of π-d-Conjugated Coordination Polymers Enabling Robust Sodium-Ion Batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 18769–18776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiee, N. Sustainable metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) for drug delivery systems. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 35, 106244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Y.; Chen, C.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, P.; Fei, J. An electrochemical sensor based on Ce-MOF-derived Ce-doped poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) composite for efficient determination of rutin in food. Talanta 2023, 263, 124678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Ye, W.; Cui, Y.; Li, B.; Yang, Y.; Qian, G. A metal-organic frameworks@ carbon nanotubes based electrochemical sensor for highly sensitive and selective determination of ascorbic acid. J. Mol. Struct. 2020, 1209, 127986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, B.; Di, C.-A.; Li, F.; Jin, C.; Mi, W.; Chen, L.; et al. 2D Semiconducting Metal-Organic Framework Thin Films for Organic Spin Valves. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 1118–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, P.; Lan, G.; Liu, C.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Sun, H.; Huang, W. Recent advances in synthesis of two-dimensional conductive metal-organic frameworks and their electrochemical energy storage application. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2021, 30, e00354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hmadeh, M.; Lu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Gándara, F.; Furukawa, H.; Wan, S.; Augustyn, V.; Chang, R.; Liao, L.; Zhou, F.; et al. New Porous Crystals of Extended Metal-Catecholates. Chem. Mater. 2012, 24, 3511–3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, W.-T.; Kim, S.-J.; Jang, J.-S.; Kim, D.-H.; Kim, I.-D. Catalytic Metal Nanoparticles Embedded in Conductive Metal-Organic Frameworks for Chemiresistors: Highly Active and Conductive Porous Materials. Adv. Sci. 2019, 6, 1900250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, P.; Pan, X.; Huang, J.; Gao, Y.; Guo, W.; Li, J.; Tang, M.; Wang, Z. In Situ Fabrication of Porous MOF/COF Hybrid Photocatalysts for Visible-Light-Driven Hydrogen Evolution. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 59915–59924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, W.; Lv, S.; Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, J. A Directly Grown Pristine Cu-CAT Metal-organic Framework as an Anode Material for High-energy Sodium-ion Capacitors. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 11207–11210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.-P.; Tang, H.-L.; Dong, H.; Gao, M.-Y.; Li, C.-C.; Sun, X.-J.; Wei, J.-Z.; Qu, Y.; Li, Z.-J.; Zhang, F.-M. Covalent-organic Framework Based Z-scheme Heterostructured Noble-metal-free Photocatalysts for Visible-light-driven Hydrogen Evolution. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 4334–4340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.-C.; Gao, M.-Y.; Sun, X.-J.; Tang, H.-L.; Dong, H.; Zhang, F.-M. Rational Combination of Covalent-organic Framework and Nano TiO2 by Covalent Bonds to Realize Dramatically Enhanced Photocatalytic Activity. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 266, 118586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.-H.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Tang, H.-L.; Fang, L.; Niu, G.-D.; Sun, X.-J.; Zhang, F.-M. Facile Synthesis of a Covalently Connected rGO-COF Hybrid Material by in situ Reaction for Enhanced Visible-light Induced Photocatalytic H2 Evolution. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 8949–8956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.C.; Tang, J.Y.; Wang, G.L.; Zhang, M.; Hu, X.Y. Facile synthesis of submicron Cu2O and CuO crystallites from a solid metallorganic molecular precursor. J. Cryst. Growth 2006, 294, 278–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, M.; Shang, S.; Gao, W.; Wang, X.; Hong, J.; Hua, C.; You, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. Recrystallization of 2D C-MOF Films for High-Performance Electrochemical Sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 16991–16998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uzak, D.; Atiroğlu, A.; Atiroğlu, V.; Çakıroğlu, B.; Özacar, M. Reduced Graphene Oxide/Pt Nanoparticles/Zn-MOF-74 Nanomaterial for a Glucose Biosensor Construction. Electroanalysis 2020, 32, 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Meena, V.K.; Mizaikoff, B.; Singh, S.P.; Suri, C.R. Electrochemical sensing of nitro-aromatic explosive compounds using silver nanoparticles modified electrochips. Anal. Methods 2016, 8, 7158–7169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Pan, L.; Han, X.; Ha, M.N.; Li, K.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Hou, C.; Wang, H. A portable ascorbic acid in sweat analysis system based on highly crystalline conductive nickel-based metal-organic framework (Ni-MOF). J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 616, 326–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimi, N.; Futamura, T.; Kakumoto, K.; Salehi, A.M.; Sellgren, C.M.; Holmén-Larsson, J.; Jakobsson, J.; Pålsson, E.; Landén, M.; Hashimoto, K. Blood metabolomics analysis identifies abnormalities in the citric acid cycle, urea cycle, and amino acid metabolism in bipolar disorder. BBA Clin. 2016, 5, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.-F.; Ye, J.-S.; Zhang, W.-D.; Li, C.-M.; Luong, J.H.T.; Sheu, F.-S. Selective and sensitive electrochemical detection of glucose in neutral solution using platinum-lead alloy nanoparticle/carbon nanotube nanocomposites. Anal. Chim. Acta 2007, 594, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EDQM. Genera European OMCL Network Quality Management Document: PA/PH/OMCL (18) 145 R1 CORR Evaluation of Measurement Uncertainty (Core Document) [S]. European: Guideline, 2020: 1–9. Available online: https://www.edqm.eu/documents/52006/128968/omcl-evaluation-of-measurement-uncertainty-core-document.pdf/b9b88e44-e831-4221-9926-d8c6e8afe796?t=1628491784923 (accessed on 18 April 2024).

| Samples | Actual Value (μmol/L) | Detection Value (μmol/L) | RSD (%) | Recovery (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse serum | 25 | 24.7 | 4.87 | 98.6 |

| 55 | 53.9 | 4.08 | 98.0 | |

| 285 | 282.2 | 0.67 | 99.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, S.; Li, P.; Wang, J.; Gong, J.; Lu, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, Q.; Xue, P. Detection of Ascorbic Acid by Two-Dimensional Conductive Metal-Organic Framework-Based Electrochemical Sensors. Molecules 2024, 29, 2413. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112413

Wang S, Li P, Wang J, Gong J, Lu H, Wang X, Wang Q, Xue P. Detection of Ascorbic Acid by Two-Dimensional Conductive Metal-Organic Framework-Based Electrochemical Sensors. Molecules. 2024; 29(11):2413. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112413

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Shi, Ping Li, Junyi Wang, Jun Gong, Helin Lu, Xiaobo Wang, Quan Wang, and Ping Xue. 2024. "Detection of Ascorbic Acid by Two-Dimensional Conductive Metal-Organic Framework-Based Electrochemical Sensors" Molecules 29, no. 11: 2413. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules29112413