Abstract

Introduction: Many studies have been published, but none have pooled the useful evidence available in the literature to produce guidelines and health policies promoting healthy eating styles to prevent breast cancer (BC). The present study aimed to summarize the evidence produced to date, taking a judicious, critical approach to the quality of the studies analyzed. Methods: An umbrella review method was adopted, which is a systematic review of second-level studies, meta-analyses and literature reviews. Results: In all, 48 studies were considered: 32 meta-analyses, 4 pooled analyses, 5 systematic reviews, and 7 qualitative reviews. A higher intake of total meat, or red or processed meats, or foods with a high glycemic index, or eggs would seem to be associated with a higher risk of BC. Some foods, such as vegetables, would seem instead to have an inverse association with BC risk. One meta-analysis revealed an inverse association between citrus fruit and mushroom consumption and BC. Some nutrients, such as calcium, folate, vitamin D, lignans and carotenoids, also seem to be inversely associated with BC risk. The evidence is still conflicting as concerns exposure to other dietary elements (e.g., polyunsaturated fatty acids, dairy foods). Conclusion: Nutrition is one of the most modifiable aspects of people’s lifestyles and dietary choices can affect health and the risk of cancer. Overall, adhering to a healthy eating style may be associated with a significant reduction in the risk of BC.

1. Introduction

Breast cancer (BC) is the most frequently diagnosed female cancer, accounting for 29% of cancers in women [1]. It is important for primary prevention to include reducing modifiable risk factors, such as obesity, a sedentary lifestyle, and a poor diet. Each of these factors can have various effects, depending on breast tissue type and age (premenopausal and menopausal).

As concerns diet, the role of alcohol as a risk factor has been well established: the results of the 2011 EPIC (European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition) survey found that 5% of BCs could be attributable to alcohol consumption [2]. Numerous studies have addressed the role of several other foods too, sometimes reporting divergent results. For example, according to the EPIC survey, a diet rich in saturated fat is associated with a higher risk of estrogen- and progesterone-positive cancer, with a significantly higher hazard ratio [3]. Similar results emerged from a Swedish cohort survey, in which a high dietary fat consumption seemed to lead to a significant increase in the risk of developing BC [4]. On the other hand, a case-control survey conducted in China in 2008 found no significant association between the various types of dietary fat and the odds of cancer [5]. Red meat and animal proteins seem to be associated with an increase in the risk of neoplastic disease: Jansen suggested that consuming them in large amounts anticipates menarche, and this is recognized as a risk factor and predictor of BC [6].

Several epidemiological studies have shown that consuming soy products is associated with a lower incidence of hormone-related tumors, including BC, due to the properties of isoflavones and phytoestrogens [7,8,9].

Despite the many studies conducted on the topic, the evidence in the literature has yet to be pooled and used for the purpose of drawing up guidelines and health policies to promote healthy eating styles. The aim of the present work was thus to obtain a synthesis of the scientific evidence produced over the last 15 years regarding the association between nutrition and BC. The umbrella review approach was adopted, which entails conducting a systematic review of second-level studies, meta-analyses, and literature reviews, and summarizing the evidence available to date in the light of a judicious critical assessment of the quality of the studies involved.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

An umbrella review was conducted, which involved critically examining the literature, starting from a synthesis of the previously-published second-level research, and performing a critical review of all available evidence [10,11].

2.2. Sources

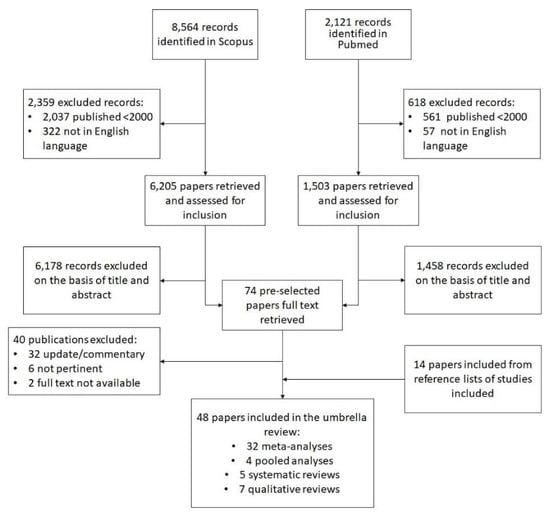

A comprehensive search (see Figure 1) was conducted in the PubMed (Medline) and Scopus databases using combined MeSH terms: (“breast neoplasm” (MeshTerm) OR “breast cancer” OR “breast tumor”) AND (“diet” (MeshTerm) OR “alimentation” OR “nutrition”) AND (“prevention” (MeshTerm) OR “risk” (MeshTerm) OR “association” (MeshTerm)) from 2000 to February 2016. The search concerned meta-analyses, pooled analyses, systematic reviews, and qualitative reviews on the risk of BC in the female population. We checked the references for the systematic reviews and meta-analyses retrieved, and the proceedings of relevant conferences for articles missed by the electronic search. In particular, we included studies that examined the presence and intake of foods in the diet (exogenous exposure), instead of just measuring endogenous nutrients. Studies with the subsequent characteristics were excluded:

Figure 1.

The research strategy used to identify the articles for the umbrella review.

- General and descriptive reports, comments and updates without any reported association measures;

- Studies on populations or groups at increased risk;

- Analyses of dietary supplements or studies examining the combined effect of physical activity and diet;

- Studies involving BC recurrence;

- Studies written in languages other than Italian or English.

2.3. Data Extraction

We first extracted the general characteristics of each eligible systematic review or meta-analysis, the first author’s name, the year of publication, the type of epidemiological design, the total size of the samples in all the studies included in a review. Then, we extracted the main findings of each study, including how exposure was measured and the overall results, and we summarized the meta-analytic estimates. Finally, we input details of the limitations of the study, and the authors’ recommendations. Two investigators (M.P., L.L.) independently searched the literature, assessed the eligibility of the papers they retrieved, and extracted the data. Disagreements were solved by discussion with a third investigator (A.B.).

2.4. Study Quality Assessment

The PRISMA (preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses) checklist, developed in 2009 [12,13], was used for a critical assessment of the internal validity of the reviews and meta-analyses considered. A checklist was compiled for each study included in the umbrella review (see Table S3).

3. Results

Our literature search identified 8564 results in Scopus and 2121 in PubMed (Figure 1). Then 2359 of the former studies and 618 of the latter were removed after applying publication and language filters. Another 6178 and 1503 studies were excluded after screening the abstracts and titles. In the end, 74 studies were included in the pre-selection phase, and 40 of them were deleted after reading the full text, leaving 34 studies. At this point, 14 further articles were drawn from the lists of references of the reviews considered. A total of 48 studies were tabulated for the purposes of our umbrella review: 32 meta-analyses, 4 pooled analyses, 5 systematic reviews, and 7 other reviews. The quality of these studies varied considerably: the meta-analyses scored a mean 20.1 points on the PRISMA checklist, the pooled analyses 15.5, the systematic reviews 15.2, and the other reviews 9 points.

Table 1 contains data concerning the general characteristics of the studies identified, Table 2 shows the exposure measures and main findings of the studies, Table 3 shows the conclusions and recommendations, and Tables S1 and S2 show summaries of the results of the studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the umbrella review.

Table 2.

Results of studies included in the umbrella review.

Table 3.

Conclusions and limitations of studies included in the umbrella review.

3.1. Dietary Patterns

The umbrella review ultimately included five studies (two meta-analyses [14,15], one three-cohort analysis [16], two systematic reviews [17,18]) on the association between dietary patterns and BC risk. A diet was judged to be “healthy” if it included plenty of fiber and limited amounts of saturated fat, animal proteins, and refined sugars. The Mediterranean diet (MD) also contemplates a moderate consumption of red wine, and the use of extra-virgin olive oil for seasoning. These two (healthy and MD) eating patterns have been associated with a protective role against the development of BC [14,17,18] (Brennan, all studies combined: Odds Ratio (OR) 0.89, 95% CI 0.82–0.99). A systematic review [18], which included five cohort studies and three case-control studies, found that the case-control studies had identified an inverse association between MD and BC risk, in both pre- and post-menopausal women, but the cohort studies reported controversial results. One study that examined three cohorts using a standardized method found no association between a vegetable-based diet (characterized by high intakes of vegetables, legumes, fruit, pasta, fish, and oil) and BC risk in any of the cohorts [16]. This goes to show that the literature still does not offer a clear evidence of the association between a healthy diet and the risk of BC.

The Western diet includes large amounts of refined sugars, proteins, saturated fats, and alcohol, and—judging from case-control studies alone—it appears to be associated with a higher risk of BC (OR 1.31, 95% CI 1.05–1.63 [14]). On the other hand, when Brennan combined all types of study, there was no evidence of any difference in the risk of BC for women in the highest category of intake of Western/unhealthy dietary patterns compared with the lowest category (OR = 1.09, 95% CI: 0.98, 1.22).

3.2. Foods

Five studies (two meta-analyses [19,20], one systematic review [21], one pooled analysis [22] and one qualitative review [23]) examined the association between BC risk and red and processed meat consumption. Guo’s meta-analysis [19] found a positive association between the risk of BC and both red meat (summary RR 1.10, 95% CI 1.02–1.19) and processed meat (summary RR 1.08, 95% CI 1.01–1.15), and Taylor [20] reported an association between red meat consumption and a higher BC risk in premenopausal women (summary RR 1.24, 95% CI 1.08–1.42) [24]. On the other hand, the pooled study [22] found no significant associations between the intake of total meat, red meat or white meat, and BC risk.

It emerged from one meta-analysis [25] that a high weekly rate of egg consumption was associated with an increased risk of developing BC, that was only significant in women of postmenopausal age (RR estimates: 1.06; 95% CI 1.02–1.10).

Of the four studies that considered dairy food consumption (two meta-analyses [26,27], one pooled analysis [22], and one systematic review [28]), two reported an inverse association between the consumption of dairy products and the risk of BC [26,27].

Eleven of the studies analyzed the association between BC and the intake of soy foods, phytoestrogens, isoflavones, and lignans (six meta-analyses [9,29,30,31,32,33], three systematic reviews [22,28,34], and three qualitative reviews [35,36,37]). Three of these studies [29,32,34] demonstrated a significant inverse association between BC and a high lignans consumption in postmenopausal women, while two others [31,36] detected stronger evidence of this association in premenopausal women. The protective role of soy and phytoestrogens was recognized as significant in another seven studies [9,21,28,30,33,35,37].

Seven studies (three meta-analyses [24,33,38], two systematic reviews [21,28], one qualitative review [23], and one pooled analysis [39]) investigated dietary fiber: the three meta-analyses confirmed its protective effect against BC, the pooled analysis [39] found an inverse borderline association, while one of the systematic reviews [21] and the qualitative review [23] found no association between fruit fiber intake and the incidence of BC. The other systematic review only found a protective role for vegetable consumption, but no significant association with fruits or fruit fiber [28]. In another meta-analysis [40], Song reported a statistically significant association between citrus fruit consumption and the risk of developing BC (summary RR 0.90; 95% CI 0.85–0.96). A further meta-analysis [41] showed a significant inverse association between mushroom consumption and the risk of BC, in both premenopausal women (RR 0.96, 95% CI 0.91–1.00), and postmenopausal women (summary RR 0.94; 95% CI 0.91–0.97). The scientific evidence of any role for green tea in preventing BC is rather weak: one meta-analysis [42] and one systematic review [28] included in our umbrella review found no significant association, while a subgroup analysis showed a statistically significant inverse association in case-control studies (summary RR 0.56; 95% CI 0.38–0.83).

3.3. Nutrients

Eight of the studies (including four meta-analyses [33,43,44,45], two systematic reviews [21,28], one pooled analysis [46] and one qualitative review [23]) analyzed fat intake and the risk of BC. One meta-analysis [43] found no statistically significant association (summary RR estimate 1.11, 95% CI 0.91–1.36); one of the systematic reviews [29] and the qualitative review [23] obtained similar results. Another four studies found an increased risk of BC in women with a high intake of total fat [21,33,44] (Boyd et al. [44]) (summary RR 1.13, 95% CI 1.03–1.25) and saturated fat [46] (summary RR 1.19, 95% CI 1.00–1.19); one study found a positive association between a high intake of total fat and BC risk in postmenopausal women only [45] (summary RR 1.04, 95% CI 1.01–1.07).

Only one of the two meta-analyses included in our review [47,48] showed a modest increase in the risk of BC for women with dietary patterns associated with a high glycemic index (GI) or glycemic load (GL) [48]. Another two studies investigating the association between foods with a high GI or GL and the risk of BC also produced controversial results [21,28].

The consumption of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) was examined in seven studies (five meta-analyses [44,45,49,50,51], one systematic review [21], and one pooled analysis [46]). Two meta-analyses [49,50] found a significant protective association, three studies [44,46,51] reported a statistically insignificant inverse association, and another two studies [21,45] identified a higher risk of BC in women with a high PUFA consumption (summary RR: 1.07; 95% CI 1.01–1.14).

As for vitamin D and calcium, three studies (two meta-analyses [52,53] and one qualitative review [54]) considered these factors, and their protective effect was confirmed.

Three studies (two meta-analyses [55,56], and one qualitative review [57]) tested the association between folate consumption and the risk of BC, finding no significant inverse association overall. The only study that considered flavonoids and flavones (one meta-analysis [58]) concluded that the risk of BC was significantly reduced in women with a high overall consumption of flavonoids (RR 0.88; 95% CI 0.80–0.96), and flavones (RR 0.80; 95% CI 0.76–0.91). One meta-analysis [59] and one systematic review [28] investigated the relationship between carotenoid consumption and BC: the meta-analysis found that α-carotene and β-carotene consumption had a significant protective effect against BC, while the systematic review showed no such association. One systematic review [28] studied the association between BC and vitamins A, B, C and E, finding no such association in ten cohort studies; a positive association between vitamin E and BC emerged in one cohort study.

The overall results of the studies are summarized in Tables S1 and S2.

4. Discussion

Judging from this review, a higher intake of total meat, or red or processed meats, or of foods with a high GI, or eggs would seem to be associated with a higher risk of BC. Other foods, such as vegetables, soy and carotenoids, would seem to be inversely associated with BC risk. One meta-analysis demonstrated an inverse association between BC and the consumption of citrus fruits and mushrooms. Some nutrients also seem to be inversely associated with BC risk, including calcium, folate, vitamin D, lignans, and carotenoids. As concerns exposure to other dietary elements (polyunsaturated fatty acids, dairy foods), the evidence is still conflicting.

4.1. Dietary Patterns

Our findings indicate that most of the literature analyzed here attributed a protective role to the MD [19,51]. Research has shown that this type of diet is rich in antioxidants, which probably inhibit the synthesis and activity of growth factors promoting the development of cancer cells. A more recent meta-analysis of studies on postmenopausal BC [61] found an inverse association between MD and BC risk, when alcohol was excluded (summary Hazard Ratio (HR) 0.92; 95% CI 0.87, 0.98), while this association disappeared when alcohol was included. This might indicate that the MD could even be used as a primary BC prevention measure, especially in postmenopausal women. Some authors have said that calorie balance, adiposity control, and exercise are important to BC prevention too, as well as the composition and quality of the diet [62,63,64,65]. The MD also seems to have a beneficial influence against the risk of BC regardless of body weight and BMI [66,67,68,69]. The literature on the traditional MD has demonstrated that dietary fiber has multiple protective effects, which include inhibiting intestinal estrogen reabsorption, and modulating cholesterol levels and glucose release, thereby reducing BC risk [70]. The protective effect of fruit and vegetables seems to be linked to their high content of beneficial substances (vitamins, minerals, salicylates, phytosterols, glucosinolates, polyphenols, phytoestrogens, sulfides, lectins, etc.), which have an antioxidant action, preventing the activation of many carcinogens, suppressing spontaneous mutations, and protecting cellular structures and DNA against the oxidative damage generated by metabolic processes [70,71,72]. Leafy vegetables are rich in lutein, zeaxanthin, folates, vitamin A and carotenoids, which are antioxidant and also able to regulate estrogen metabolism and inhibit tumor growth [73,74]. Fruits seem to have an anti-carcinogenic potential due to their antioxidant properties; this is especially true of red fruits, which contain ellagic acid, quercitin and anthocyanins. These substances stimulate the mechanisms behind the elimination of toxic substances, inhibit angiogenesis, reduce inflammation, and promote cellular apoptosis mechanisms [71,75]. Some mushroom-derived substances, like polysaccharides, are known for their anti-tumor and immunomodulatory properties, for enhancing immune system activity and protecting against tumor recurrences [76]. A pooled analysis of eight large cohort studies did not strongly associate the intake of fruit and vegetables with the risk of BC, however [46]. Another comparative study of three cohorts also indicated that a diet rich in vegetables and fruits, but also characterized by other foods such as oil and fish, was not significantly related to a lower risk of BC [46].

The studies included in the present review indicated that the Western diet, which involves a high intake of refined sugars, saturated fats and alcohol, is strongly associated with an increased risk of BC [14,17]. This type of diet influences inflammatory processes, and induces an increase in adiposity and the production of growth factors and hormones (estrogen and testosterone).

Overall, however, the studies reviewed did not produce consistent results concerning specific dietary patterns and the risk of BC. Further studies could probably be conducted using machine learning techniques: this type of analysis could test clusters of foods not defined a priori—instead of prototypic dietary patterns—in terms of their association with BC risk, or BC prevention. In fact, a diet can include numerous foods that might have opposite effects, in which case analyzing preset eating patterns would be unable to produce evidence of any clear association.

4.2. Foods

The significant association demonstrated by the EPIC study [77] between red or processed meat consumption and a higher risk of BC, and BC-related mortality, was also confirmed in our umbrella review [19,20]. Apart from the related fat intake, various other factors appear to be involved in the carcinogenic potential of red and processed meat: the presence of carcinogens or their precursors (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, heterocyclic aromatic amines, nitrosamines) produced by food treatments like cooking, salting or smoking; a high intake of animal proteins, with a potential increase in insulin-like growth factor (IGF) levels; hormone residues contained in meat from intensive farming; and the fact that intestinal fermentation of animal proteins raises the concentration of some polyamines, which are fundamental to cell proliferation.

A significant association also emerged between egg consumption and a higher risk of BC [24], but this relationship needs to be confirmed. The most plausible mechanism behind the carcinogenic potential of eggs might relate to their high cholesterol content (425 mg per 100 g) [24], given the recommended daily dose of 300 mg. Cholesterol is a precursor of steroid hormones, so it can influence estrogen activity and contribute to cellular inflammation, a crucial component in BC progression [78]. However, some evidence points to the association between eggs and BC being not necessarily due to cholesterol [79]: when fried at high temperatures, eggs also become a source of heterocyclic amines and several carcinogenic components, so their mutagenic activity can increase in some conditions (cooking at high temperatures and with inappropriate oil) [80].

Our umbrella review showed that studies consistently provided evidence of a protective effect of soy in the diet against the risk of BC [9,29,30,32,34,35,36], especially among postmenopausal women [28,31,33]. Phytoestrogens are structurally and functionally natural substances similar to estradiol, with a similar estrogenic activity. The evidence indicates a lower BC risk in consumers of soybean and phytoestrogen-containing plants, particularly in Asian populations (who are exposed to such foods from childhood), and in postmenopausal women. The protective effect of these foods is due to the agonist or antagonist actions against estrogens in breast tissue, reducing blood levels of estradiol [81,82] and consequently also the risk of estrogen receptor positive (ER+)/progesterone receptor positive (PR+) BC.

Finally, our umbrella review found that consuming lean dairy products was associated with a lower risk of BC [25,26], probably due to the protective effect of vitamin D and calcium [52,53,54]. Breast tissue has receptors to the biologically active form of vitamin D, calcitriol 1,25(OH)2D, which appears to be able to directly and indirectly control more than 200 genes, including those responsible for cell proliferation, malignant cell differentiation, apoptosis and angiogenesis [83]. In contrast, there are also reports of dairy product consumption leading to an increased estrogen hormone intake, which can enhance the penetrance of BC associated with Breast Related Cancer Antigens (BRCA) mutations [84]. In addition, milk has the potential to raise blood levels of growth factors, and a diet rich in animal protein is associated with high serum IGF-1 levels, which are strongly associated with a greater risk of BC [85,86].

The consumption of citrus fruits, rich in vitamin C, β-carotene, quercitin and folate, seems to have a very positive impact on health due to the antioxidant, immune-stimulant, and detoxifying properties, and a capacity to modulate insulin sensitivity and cholesterol levels [87]. In fact, our review found a 10% lower BC risk in women who consumed large amounts of citrus fruit.

4.3. Nutrients

A significant inverse association has been demonstrated between BC risk and consumption of carotenoids [88], which have antioxidant properties. These compounds, especially β-carotenes, are capable of binding and eliminating free radicals, and repairing DNA damage, inhibiting cell proliferation, inducing apoptosis, and suppressing angiogenesis [89]. Flavonoids have been acknowledged to have a role in protecting against and preventing non-communicable diseases [90,91,92,93], and neoplasms in particular, due to their potent antioxidant and DNA repairing activity. In this review, the dietary impact of various subclasses of flavonoids was analyzed, and it proved significant for flavonols, flavones, and flavan-3-ol swell classes, particularly after menopause. Folic acid, a soluble member of the vitamin B group, is needed for all DNA synthesis, repair and methylation reactions, so folate deficiency in the diet can negatively affect cell division and DNA repair mechanisms. The studies assessed in our umbrella review generally reported inconsistent results on the association between folic acid and BC, however.

Foods with a high GI, such as simple sugars, refined carbohydrates and starches, induce a rapid increase in blood glucose, and consequently stimulate insulin production. High levels of insulin cause the production of IGF-1 and testosterone, which are recognized as risk factors for BC. In addition, chronic hyperinsulinemia with associated insulin resistance has a key role in the etiology of BC as it induces the production of IGF-1, which is capable of causing mutagenic changes [94]. The studies included in our review [47,48] demonstrated no strong association between high GI food consumption and any increased risk of BC, however; this is probably due to reliability issues with the measurement indices adopted.

On the whole, our review identified a moderate risk of BC in women with a high total fat and/or saturated fat intake [32,44,46]. There was also evidence to support this higher BC risk applying especially to postmenopausal women [95,96,97], and the consumption of saturated fat is also associated with a higher likelihood of obesity [98,99,100,101,102,103,104]. Obesity and overweight, together with lack of exercise, are established risk factors for BC [105,106]. A diet rich in saturated fat also increases estrogen synthesis, leading to an increased cell proliferation and a consequently higher BC risk [107,108].

On the other hand, our review found that polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) can have a role in reducing BC risk [49,50], although some studies found controversial results [21,45]. A possible explanation of the discrepancy of results concerns the fact that the two studies that found a protective effect of the PUFAs against the BC specifically examined the intake of n-3/n-6 PUFAs [49] and marine n-3 PUFA [50]. On the contrary, in the two studies [21,45] which gave an opposite result, the association between BC and the PUFA subtypes was not examined. The n-3 PUFA family compete for the same metabolic pathway with the n-6 PUFA family, which is associated with cell proliferation in breast tissue. The n-3 PUFA family reduces inflammation, controls triglyceride levels, and thus reduces the risk of BC via several mechanisms, i.e., by altering the composition of the phospholipid cell membranes, inhibiting arachidonic acid (ARA) metabolism and pro-inflammatory molecule production, and modulating the expression and function of various receptors, transcription factors, and signaling molecules [109]. Marine-derived n-3 PUFA would seem to have a protective effect against the development of BC [110], particularly in postmenopausal women, whereas n-6 PUFA contribute to carcinogenic mechanisms with the production of pro-inflammatory eicosanoids, such as prostaglandin E2, which is implicated in angiogenic processes and in the suppression of cancer cell apoptosis [109,111].

Overall, our study confirms the content of the third report from the World Cancer Research Fund [112], which found moderate evidence of the following: consuming non-starchy vegetables might reduce the risk of estrogen-receptor-negative (ER-) BC; consuming foods containing carotenoids, or adopting diets high in calcium might reduce the risk of BC in both premenopausal and postmenopausal women; and consuming dairy products might reduce the risk of BC, but only in premenopausal women. Our study also indicated that other foods and nutrients, including soy, folate, vitamin D, and lignans, seem to be inversely associated with BC.

This umbrella review of studies investigating the associations between diet, or specific foods or nutrients and BC reveals the weaknesses of the observational studies and reviews published on this topic (as shown in Table 3). The main shortcoming concerns measurement errors in dietary intake assessments, which bias the estimates of any such associations. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews of case-control studies may also be affected by recall and interview bias, often revealing associations that are not confirmed in cohort studies. Some studies also adjusted inconsistently for potential confounders (e.g., physical activity, often associated with both outcome and exposure), and this could result in residual confounding elements that would bias the estimates emerging from a meta-analysis.

5. Conclusions

Nutrition is one of the most modifiable aspects of lifestyle, and nutritional choices can affect people’s health and the risk of cancer. Active strategies are warranted, including educational/behavioral interventions in high-risk groups, to promote healthy eating habits.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/13/4731/s1, Table S1: Summary of measures of BC risk associated with dietary exposures—For META-ANALYSES only; Table S2: Summary of measures of BC risk associated with dietary exposures; Table S3: Quality of studies included in the umbrella review.

Author Contributions

Study conception and design: A.B.; acquisition of data, review literature: M.P., L.L., G.G.; interpretation of data: G.G., A.B., V.B.; drafting of manuscript: G.G., L.L.; critical revision: A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no financial or other relationships that might lead to a conflict of interest.

References

- Tumore al Seno—Tumori AIRC. Available online: http://www.airc.it/tumori/tumore-al-seasp (accessed on 31 August 2017).

- Schütze, M.; Boeing, H.; Pischon, T.; Rehm, J.; Kehoe, T.; Gmel, G.; Olsen, A.; Tjønneland, A.M.; Dahm, C.C.; Overvad, K.; et al. Alcohol attributable burden of incidence of cancer in eight European countries based on results from prospective cohort study. BMJ 2011, 342, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieri, S.; Chiodini, P.; Agnoli, C.; Pala, V.; Berrino, F.; Trichopoulou, A.; Benetou, V.; Vasilopoulou, E.; Sánchez, M.J.; Chirlaque, M.; et al. Dietary fat intake and development of specific breast cancer subtypes. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2014, 106, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattisson, E.; Wirfält, P.; Wallström, B.; Gullberg, H.O.L.; Berglund, G. High fat and alcohol intakes are risk factors of postmenopausal breast cancer: A prospective study from the Malmö diet and cancer cohort. Int. J. Cancer 2004, 110, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.-X.; Ho, S.C.; Lin, F.-Y.; Chen, Y.-M.; Cheng, S.-Z.; Fu, J.-H. Dietary fat intake and risk of breast cancer: A case-control study in China. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. 2011, 20, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, E.C.; Marin, C.; Mora-Plazas, M.; Villamor, E. Higher childhood red meat intake frequency is associated with earlier age at menarche. J. Nutr. 2016, 146, 792–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varinska, L.; Gal, P.; Mojzisova, G.; Mirossay, L.; Mojzis, J. Soy and breast cancer: Focus on angiogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 11728–11749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messina, M.; McCaskill-Stevens, W.; Lampe, J.W. Addressing the soy and breast cancer relationship: Review, commentary, and workshop proceedings. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2006, 98, 1275–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Yu, M.C.; Tseng, C.C.; Pike, M.C. Epidemiology of soy exposures and breast cancer risk. Br. J. Cancer 2008, 98, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aromataris, E.; Fernandez, R.; Godfrey, C.M.; Holly, C.; Khalil, H.; Tungpunkom, P. Summarizing systematic reviews. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aromataris, E.; Fernandez, R.; Godfrey, C.; Holly, C.; Khalil, H.; Tungpunkom, P. Methodology for JBI Umbrella Reviews. Joanna Briggs Inst. Rev. Man. 2014, 1–34. Available online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4367&context=smhpapers (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D. PRISMA CHECKLIST. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, 7. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D.; Altman, D.G.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J. PRISMA Statement. Epidemiology 2011, 22, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennan, S.F.; Cantwell, M.M.; Cardwell, C.R.; Velentzis, L.S.; Woodside, J.V. Dietary patterns and breast cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 91, 1294–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwingshackl, L.; Hoffmann, G. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Int. J. Cancer 2014, 135, 1884–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Männistö, S.; Dixon, L.B.; Balder, H.F.; Virtanen, M.J.; Krogh, V.; Khani, B.R.; Berrino, F.; van den Brandt, P.A.; Hartman, A.M.; Pietinen, P.; et al. Dietary patterns and breast cancer risk: Results from three cohort studies in the DIETSCAN project. Cancer Causes Control 2005, 16, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albuquerque, R.C.R.; Baltar, V.T.; Marchioni, D.M.L. Breast cancer and dietary patterns: A systematic review. Nutr. Rev. 2014, 72, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farsinejad-Marj, M.; Talebi, S.; Ghiyasvand, R.; Miraghajani, M. Adherence to Mediterranean diet and risk of breast cancer in premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Arch. Iran. Med. 2015, 18, 786–792. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Wei, W.; Zhan, L. Red and processed meat intake and risk of breast cancer: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2015, 151, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, V.H.; Misra, M.; Mukherjee, S.D. Is red meat intake a risk factor for breast cancer among premenopausal women? Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2009, 117, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourouti, N.; Kontogianni, M.D.; Papavagelis, C.; Panagiotakos, D.B. Diet and breast cancer: A systematic review. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 66, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Missmer, S.A.; Smith-Warner, S.A.; Spiegelman, D.; Yaun, S.S.; Adami, H.O.; Beeson, W.L.; Van Den Brandt, P.A.; Fraser, G.E.; Freudenheim, J.L.; Goldbohm, R.A.; et al. Meat and dairy food consumption and breast cancer: A pooled analysis of cohort studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2002, 31, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanf, V.; Gonder, U. Nutrition and primary prevention of breast cancer: Foods, nutrients and breast cancer risk. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2005, 123, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gandini, S.; Merzenich, H.; Robertson, C.; Boyle, P. Meta-analysis of studies on breast cancer risk and diet: The role of fruit and vegetable consumption and the intake of associated micronutrients. Eur. J. Cancer 2000, 36, 636–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, R.; Qu, K.; Jiang, Z.; Yang, X.; Gao, P. Egg consumption and breast cancer risk: A meta-analysis. Breast Cancer 2014, 21, 251–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.-Y.; Zhang, L.; He, K.; Qin, L.-Q. Dairy consumption and risk of breast cancer: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011, 127, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, J.; Shen, M.; Du, S.; Chen, T.; Zou, S. The association between dairy intake and breast cancer in western and Asian populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Breast Cancer 2015, 18, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- .Michels, K.B.; Mohllajee, P.A.; Roset-Bahmanyar, E.; Beehler, G.P.; Moysich, K.B. Diet and breast cancer: A review of the prospective observational studies. Cancer 2007, 109, 2712–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, K.; Zaineddin, A.K.; Vrieling, A.; Linseisen, J.; Chang-Claude, J. Meta-analyses of lignans and enterolignans in relation to breast cancer risk. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.-Y.; Qin, L.-Q. Soy isoflavones consumption and risk of breast cancer incidence or recurrence: A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2011, 125, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trock, B.J.; Leena, H.C.; Clarke, R. Meta-analysis of soy intake and breast cancer risk. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2006, 98, 459–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velentzis, L.S.; Cantwell, M.M.; Cardwell, C.; Keshtgar, M.R.; Leathem, A.J.; Woodside, J.V. Lignans and breast cancer risk in pre- and post-menopausal women: Meta-analyses of observational studies. Br. J. Cancer 2009, 100, 1492–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-C.; Zheng, D.; Sun, J.-J.; Zou, Z.-K.; Ma, Z.-L. Meta-analysis of studies on breast cancer risk and diet in Chinese women. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2015, 8, 73–85. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mourouti, N.; Panagiotakos, D.B. Soy food consumption and breast cancer. Maturitas 2013, 76, 118–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duffy, C.; Perez, K.; Partridge, A. Implications of phytoestrogen intake for breast cancer. Cancer J. Clin. 2007, 57, 60–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lof, M.; Weiderpass, E. Epidemiologic evidence suggests that dietary phytoestrogen intake is associated with reduced risk of breast, endometrial, and prostate cancers. Nutr. Res. 2006, 26, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peeters, P.H.M.; Keinan-Boker, L.; van der Schouw, Y.T.; Grobbee, D.E. Phytoestrogens and breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2003, 77, 71–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aune, D.; Chan, D.S.; Greenwood, D.C.; Vieira, A.R.; Rosenblatt, D.A.; Vieira, R.; Norat, T. Dietary fiber and breast cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, 1394–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Warner, S.A.; Spiegelman, D.; Yaun, S.S.; Adami, H.O.; Beeson, W.L.; van den Brandt, P.A.; Folsom, A.R.; Fraser, G.E.; Freudenheim, J.L.; Goldbohm, R.A.; et al. Intake of fruits and vegetables and risk of breast cancer a pooled analysis of cohort studies. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2001, 285, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.K.; Bae, J.M. Citrus fruit intake and breast cancer risk: A quantitative systematic review. J. Breast Cancer 2013, 16, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zou, L.; Chen, W.; Zhu, B.; Shen, N.; Ke, J.; Lou, J.; Song, R.; Zhong, R.; Miao, X. Dietary mushroom intake may reduce the risk of breast cancer: Evidence from a meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e93437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seely, D.; Mills, E.J.; Wu, P.; Verma, S.; Guyatt, G.H. The effects of green tea consumption on incidence of breast cancer and recurrence of breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2005, 4, 144–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, D.D.; Morimoto, L.M.; Mink, P.J.; Lowe, K.A. Summary and meta-analysis of prospective studies of animal fat intake and breast cancer. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2010, 23, 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boyd, N.F.; Stone, J.; Vogt, K.N.; Connelly, B.S.; Martin, L.J.; Minkin, S. Dietary fat and breast cancer risk revisited: A meta-analysis of the published literature. Br. J. Cancer 2003, 89, 1672–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, L.B. A meta-analysis of fat intake, reproduction, and breast cancer risk: An evolutionary perspective. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 2011, 23, 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith-Warner, S.A.; Spiegelman, D.; Adami, H.O.; Beeson, W.L.; van den Brandt, P.A.; Folsom, A.R.; Fraser, G.E.; Freudenheim, J.L.; Goldbohm, R.A.; Graham, S.; et al. Types of dietary fat and breast cancer: A pooled analysis of cohort studies. Int. J. Cancer 2001, 92, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulholland, H.G.; Murray, L.J.; Cardwell, C.R.; Cantwell, M.M. Dietary glycaemic index, glycaemic load and breast cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Cancer 2008, 99, 1170–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullie, P.; Koechlin, A.; Boniol, M.; Autier, P.; Boyle, P. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition relation between breast cancer and high glycemic index or glycemic load: A meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies relation between breast cancer and high glycemic index or glycemic load. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Ren, X.-L.; Fu, Y.-Q.; Gao, J.-L.; Li, D. Ratio of n-3/n-6 PUFAs and risk of breast cancer: A meta-analysis of 274135 adult females from 11 independent prospective studies. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.-S.; Hu, X.-J.; Zhao, Y.-M.; Yang, J.; Li, D. Intake of fish and marine n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and risk of breast cancer: Meta-analysis of data from 21 independent prospective cohort studies. BMJ 2013, 346, F3706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhai, S.; Li, W.; Meng, Q. Linoleic acid and breast cancer risk: A meta-analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2015, 19, 1457–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Hu, P.; Xie, D.; Qin, Y.; Wang, F.; Wang, H. Meta-analysis of vitamin D, calcium and the prevention of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2010, 121, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gissel, T.; Rejnmark, L.; Mosekilde, L.; Vestergaard, P. Intake of vitamin D and risk of breast cancer—A. meta-analysis. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2008, 111, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Y.; Rohan, T.E. Vitamin D, calcium, and breast cancer risk: A review. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2006, 15, 1427–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Li, C.; Li, X.; Li, J.; Chu, R.; Wang, H. Higher dietary folate intake reduces the breast cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Cancer 2014, 110, 2327–2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, S.C.; Giovannucci, E.; Wolk, A. Folate and risk of breast cancer: A. meta-analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2007, 99, 64–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichholzer, M.; Lüthy, J.; Moser, U.; Fowler, B. Folate and the risk of colorectal, breast and cervix cancer: The epidemiological evidence. Swiss Med. Wkly. 2001, 131, 539–549. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hui, C.; Qi, X.; Qianyong, Z.; Xiaoli, P.; Jundong, Z.; Mantian, M. Flavonoids, flavonoid subclasses and breast cancer risk: A meta-analysis of epidemiologic studies. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e54318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, F.; Wang Yi, B.; Zhang, W.; Liang, J.; Lin, C.; Li, D.; Wang, F.; Pang, D.; Zhao, Y. Carotenoids and breast cancer risk: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2012, 131, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, R.E.; Pericleous, M.; Mandair, D.; Whyand, T.; Caplin, M.E. The role of dietary factors in prevention and progression of breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 2014, 34, 6861–6875. [Google Scholar]

- van den Brandt, P.A.; Schulpen, M. Mediterranean diet adherence and risk of postmenopausal breast cancer: Results of a cohort study and meta-analysis. Int. J. Cancer 2017, 140, 2220–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, K.L.; Foster-Schubert, K.E.; Alfano, C.M.; Wang, C.C.; Wang, C.Y.; Duggan, C.R.; Mason, C.; Imayama, I.; Kong, A.; Xiao, L. Reduced-calorie dietary weight loss, exercise, and sex hormones in postmenopausal women: Randomized controlled trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012, 30, 2314–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pasanisi, P.; Berrino, F.; de Petris, M.; Venturelli, E.; Mastroianni, A.; Panico, S. Metabolic syndrome as a prognostic factor for breast cancer recurrences. Int. J. Cancer 2006, 119, 236–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frank, L.L.; Sorensen, B.E.; Yasui, Y.; Tworoger, S.S.; Schwartz, R.S.; Ulrich, C.M.; Irwin, M.L.; Rudolph, R.E.; Rajan, K.B.; Stanczyk, F.; et al. Effects of exercise on metabolic risk variables in overweight postmenopausal women: A randomized clinical trial. Obes. Res. 2005, 13, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McTiernan, A.; Tworoger, S.S.; Ulrich, C.M.; Yasui, Y.; Irwin, M.L.; Rajan, K.B.; Sorensen, B.; Rudolph, R.E.; Bowen, D.; Stanczyk, F.Z. Effect of exercise on serum estrogens in postmenopausal women: A 12-month randomized clinical trial. Cancer Res. 2004, 64, 2923–2928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trichopoulou, C.; Bamia, P.L.; Trichopoulos, D. Conformity to traditional Mediterranean diet and breast cancer risk in the Greek EPIC (European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition) cohort. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2010, 92, 620–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sieri, S.; Krogh, V.; Pala, V.; Muti, P.; Micheli, A.; Evangelista, A.; Tagliabue, G.; Berrino, F. Dietary patterns and risk of breast cancer in the ORDET cohort. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2004, 13, 567–572. [Google Scholar]

- Murtaugh, M.A.; Sweeney, C.; Giuliano, A.R.; Herrick, J.S.; Hines, L.; Byers, T.; Baumgartner, K.B.; Slattery, M.L. Diet patterns and breast cancer risk in Hispanic and non-Hispanic white women: The Four-Corners Breast Cancer Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 978–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Yu, M.C.; Tseng, C.-C.; Stanczyk, F.Z.; Pike, M.C. Dietary patterns and breast cancer risk in Asian American women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 89, 1145–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.P.; Goldman, M.; Connolly, J.M.; Strong, L.E. High-fiber diet reduces serum estrogen concentrations in premenopausal women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1991, 54, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surh, Y.-J. Cancer chemoprevention with dietary phytochemicals. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2003, 3, 768–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrino, F. Il Cibo dell’Uomo. La Via della Salute tra Conoscenza Scientifica e Antiche Saggezze; Franco Angeli: Milan, Italy, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Masala, G.; Assedi, M.; Bendinelli, B.; Ermini, I.; Sieri, S.; Grioni, S.; Sacerdote, C.; Ricceri, F.; Panico, S.; Mattiello, A.; et al. Fruit and vegetables consumption and breast cancer risk: The EPIC Italy study. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2012, 132, 1127–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribaya-Mercado, J.D.; Blumberg, J.B. Lutein and zeaxanthin and their potential roles in disease prevention. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2004, 23, 567S–587S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allegro, G.; Villarini, A. Prevenire i Tumori Mangiando con Gusto; Sperling & Kupfer: Milan, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Wasser, S. Medicinal mushrooms as a source of antitumor and immunomodulating polysaccharides. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2003, 60, 258–274. [Google Scholar]

- Rohrmann, S.; Overvad, K.; Bueno-de-Mesquita, H.B.; Jakobsen, M.U.; Egeberg, R.; Tjønneland, A.; Nailler, L.; Boutron-Ruault, M.C.; Clavel-Chapelon, F.; Krogh, V.; et al. Meat consumption and mortality—Results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. BMC Med. 2013, 11, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferretti, G.; Bacchetti, T.; Nègre-Salvayre, A.; Salvayre, R.; Dousset, N.; Curatola, G. Structural modifications of HDL and functional consequences. Atherosclerosis 2006, 184, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aune, D.; De Stefani, E.; Ronco, A.L.; Boffetta, P.; Deneo-Pellegrini, H.; Acosta, G.; Mendilaharsu, M. Egg consumption and the risk of cancer: A multisite case-control study in Uruguay. Asian Pacific J. Cancer Prev. 2009, 10, 869–876. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Zhou, Y.; Hu, R.T.; Hou, L.N.; Du, Y.J.; Zhang, X.J.; Olkkonen, V.M.; Tan, W.L. Egg consumption and risk of bladder cancer: A meta-analysis. Nutr. Cancer 2013, 65, 538–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.J.; Anderson, K.E.; Grady, J.J.; Nagamani, M. Effects of soya consumption for one month on steroid hormones in premenopausal women: Implications for breast cancer risk reduction. Cancer Epidemiol. Prev. Biomark. 1996, 5, 63–70. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L.-J.W.; Anderson, K.E.; Grady, J.J.; Kohen, F.; Nagamani, M. Decreased ovarian hormones during a soya diet: Implications for breast cancer prevention. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 4112–4121. [Google Scholar]

- Bartolozzi, G. Fisiopatologia della vitamina D (seconda parte). Medico. E. Bambino. Pagine. Elettron. 2007, 10, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Pasanisi, P.; Bruno, E.; Venturelli, E.; Manoukian, S.; Barile, M.; Peissel, B.; De Giacomi, C.; Bonanni, B.; Berrino, J.; Berrino, F. Serum levels of IGF-I and BRCA penetrance: A case control study in breast cancer families. Fam. Cancer 2011, 10, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norat, T.; Dossus, L.; Rinaldi, S.; Overvad, K.; Grønbaek, H.; Tjønneland, A.; Olsen, A.; Clavel-Chapelon, F.; Boutron-Ruault, M.C.; Boeing, H. Diet, serum insulin-like growth factor-I and IGF-binding protein-3 in European women. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 61, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, L.-Q.; He, K.; Xu, J.-Y. Milk consumption and circulating insulin-like growth factor-I level: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2009, 60, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silalahi, J. Anticancer and health protective properties of citrus fruit components. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2007, 11, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeke, C.E.; Tamimi, R.M.; Berkey, C.S.; Colditz, G.A.; Eliassen, A.H.; Malspeis, S.; Willett, W.C.; Frazier, A.L. Adolescent carotenoid intake and benign breast disease. Pediatrics 2014, 133, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Lu, Z.; Bai, L.; Shi, Z.; Zhao, W.e.; Zhao, B. β-Carotene induces apoptosis and up-regulates peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ expression and reactive oxygen species production in MCF-7 cancer cells. Eur. J. Cancer 2007, 43, 2590–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, C.; Yujie, F.; Lijia, Y.; Long, Y.; Hongxia, X.; Yong, Z.; Jundong, Z.; Qianyong, Z.; Mantian, M. MicroRNA-34a and microRNA-21 play roles in the chemopreventive effects of 3,6-dihydroxyflavone on 1-methyl-1-nitrosourea-induced breast carcinogenesis. Breast Cancer Res. 2012, 14, R80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, X.; Coburn, R.A.; Morris, M.E. Structure activity relationships and quantitative for the flavonoid-mediated inhibition of breast cancer resistance protein. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2005, 70, 627–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuhouser, M.L. Review. Dietary flavonoids and cancer risk: Evidence from human population studies. Nutr. Cancer 2004, 50, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.A.; Kasum, C.M. Dietary flavonoids: Bioavailability, metabolic effects, and safety. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 2002, 22, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, V.; Belfiore, A. Insulin receptors in breast cancer: Biological and clinical role. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 1994, 19, 324–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laamiri, F.Z.; Otmani, A.; Ahid, S.; Barkat, A. Lipid profile among Moroccan overweight women and breast cancer: A case-control study. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2013, 6, 439–445. [Google Scholar]

- Sieri, S.; Krogh, V.; Ferrari, P.; Berrino, F.; Pala, V.; Thiébaut, A.C.; Tjønneland, A.; Olsen, A.; Overvad, K.; Jakobsen, M.U.; et al. Dietary fat and breast cancer risk in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 1304–1312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, B.; Doll, R. Environmental factors and cancer incidence and mortality in different countries, with special reference to dietary practices. Int. J. Cancer 1975, 15, 617–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/publications/obesity/en/ (accessed on 29 June 2020).

- Golay, A.; Bobbioni, E. The role of dietary fat in obesity. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 1997, 21, S2–S11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Astrup, A.; Buemann, B.; Western, P.; Toubro, S.; Raben, A.; Christensen, N.J. Obesity as an adaptation to a high-fat diet: Evidence from a cross-sectional study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1994, 59, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jequier, E. Pathways to obesity. Int. J. Obes. 2002, 26, S18–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, J.O.; Melanson, E.L.; Wyatt, H.T. Dietary fat intake and regulation of energy balance: Implications for obesity. J. Nutr. 2000, 130, 284S–288S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, G.A.; Popkin, B.M. Dietary fat intake does affect obesity! Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1998, 68, 1157–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrauwen, P.; Westerterp, K.R. The role of high-fat diets and physical activity in the regulation of body weight. Br. J. Nutr. 2000, 84, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, S.C.; Wolk, A. Excess body fatness: An important cause of most cancers. Lancet 2008, 371, 536–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossus, L.; Kaaks, R. Nutrition, metabolic factors and cancer risk. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 22, 551–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Key, T.J.; Allen, N.E.; Spencer, E.A.; Travis, R.C. Nutrition and breast cancer. The Breast 2003, 12, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahmann, P.H.; Lissner, L.; Berglund, G. Breast cancer risk in overweight postmenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol. Prev. Biomark. 2004, 13, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Murff, H.J.; Shu, X.O.; Li, H.; Yang, G.; Wu, X.; Cai, H.; Wen, W.; Gao, Y.T.; Zheng, W. Dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids and breast cancer risk in Chinese women: A prospective cohort study. Int. J. Cancer 2011, 128, 1434–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Ma, D.W.L. The role of n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids in the prevention and treatment of breast cancer. Nutrients 2014, 6, 5184–5223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corso, G.; Maisonneuve, P.; Massari, G.; Invento, A.; Pravettoni, G.; De Scalzi, A.; Intra, M.; Galimberti, V.; Morigi, C.; Lauretta, M.; et al. Validation of a Novel Nomogram for Prediction of Local Relapse after Surgery for Invasive Breast Carcinoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2020, 27, 1864–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Breast Cancer. Continuous Update Project Expert Report. 2018. Available online: https://www.wcrf.org/sites/default/files/Summary-of-Third-Expert-Report-2018.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2020).

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).