Abstract

One challenge faced by many educators is strongly engaging students to improve their intrinsic motivation in learning. This paper describes the design and beta testing of two educational escape rooms targeted towards teaching students concepts related to field robotics—an area in which educational escape rooms have yet to be used. These table-top activities are designed to strongly engage students with robotics-centric puzzles, a fun narrative, and collaborative problem-solving, with validation provided by an electronic decoder box. The sets of puzzles were beta-tested by teams of academics with a robotics background and by undergraduate students. The results indicate that participants had a high level of enjoyment and intrinsic motivation to partake in the activities, although the difficulty and in-game dynamics of some of the tasks will need to be modified for widespread deployment in the classroom.

1. Introduction

Across the world, the proliferation of robotics and automation technologies continues to grow [1]. In addition to classic 3D (dull, dangerous, and dirty) applications, several factors have contributed to this growth, including high labour costs, labour shortages, inaccessibility, improved sensors, Industry 4.0 adoption, co-bots, up-scaling, and improved throughput [2,3,4]. At present, these robots are not self-replicating (and do not integrate themselves), and thus robotics engineers are required to develop, deploy, train and maintain the growing community of robots.

This growth in robotics technology naturally requires growth in training new competent robotics engineers. The last few decades have seen significant change and innovation within the higher education sector, including gamification, blended learning, online learning, and game-based learning [5,6]. These changes have had many contributing factors, including advances in technology, competition for distracted student attention (e.g., social media), demands around learning flexibility, and recent global pandemic lockdowns. Hence, many educators are looking to evolve traditional teaching formats to improve student engagement and motivation [7]. Likewise, many institutions and organisations continue to create STEM outreach programs and online content to attract the next generation of engineers and scientists [8,9].

Escape rooms are a relatively recent recreational activity which has quickly spread from its first implementation in Japan in 2007 to become a widespread activity across the world [10]. These escape rooms tend to involve small groups of participants acting as the ‘heroes’ of an adventure as they collaboratively solve puzzles within a themed set of rooms to complete the activity within a prescribed time limit [11,12]. The goal of ‘completing the activity’ is diverse and varies depending on the genre of escape room, as it may require escaping from a room, solving a mystery, or stealing a treasure. Although the concept of escape rooms is relatively new, they have roots in far older interactive activities, including puzzle hunts, interactive theater, live-action role-playing, point-and-click adventure games, adventure/quest movies and haunted houses [10].

Educational escape rooms (EERs) borrow thematic, time-pressured, collaborative problem-solving aspects from recreational escape rooms to create engaging, interactive learning experiences [13,14,15]. Often, EERs are run as table-top activities rather than as full dedicated rooms due to space, scalability, time, and cost constraints [16]. Various benefits have been attributed to EERs, including increased student engagement, positive teamwork, enjoyment, and intrinsic motivation [14].

EERs have been deployed successfully across a variety of learner levels from primary school through to university education [17,18]. EERs continue to further proliferate through undergraduate curricula, including topics as diverse as programming, chemistry, engineering, medicine, and cybersecurity [19,20,21,22,23]. Aside from the broad range of potential topics, they have also been implemented in a number of different ways, including via lockboxes, electronic decoder boxes and websites [24,25,26].

EERs can be implemented across a wide range of areas by including key elements of an appropriate narrative/theme, a series of puzzles, an answer validation system, and a clue-delivery system. Themes abound in breadth and ideally should be paired and woven into puzzles to create an element of depth and cohesion. Puzzles can take many forms (e.g., multimedia, paper, hardware props) but need to result in a single right answer to avoid simple guessing. Ideally, the answer-validation system and clue-validation systems should fit into the theme to further promote cohesion as a complete activity.

There are several frameworks that have been proposed, often with significant overlap, to aid educational escape room designers in designing and describing their designs within the academic literature. The popular escapeED framework describes the escape room activity through six sequential steps (Participants, Objectives, Theme, Puzzles, Equipment, and Evaluation), each with sub-categories, which helps provide a balanced educational escape room design [27]. Another framework is SEGAMs (Serious Escape Games) which has designers consider aspects of constraints, pedagogy, parameterisation, tests, and background [28]. The COMET framework covers five elements (Context, Objectives, Materials, Execution, and Team Dynamics) and is centred on medical education but has potential for wide applicability [29].

Eukel and Morrell developed a design framework which approximates an iterative waterfall project management technique comprising five steps: Design, Pilot, Evaluate, Redesign, and Re-evaluate [30]. Nicholson and Cable proposed a seven-step framework which encompasses Setting, Social, Story, Skills, Strategy, Simulation, and Self, with an emphasis on constructing a cohesive interactive story [13]. Room2Educ8 is a more recent framework consisting of nine elements (Empathise, Define, Contextualise, Design, Brief, Debrief, Prototype, Document, Evaluate) which follows a learner-centred approach relying on design principles [31].

The contribution of this paper is to describe and evaluate educational escape room puzzles in relation to student motivation to learn related to robotics fields of study (e.g., kinematics, sensors, odometry). Although educational escape rooms are being implemented in many domains, robotics (particularly in areas of perception and kinematics) is poorly covered by EER implementations. Hence, this study advances prior EER research with applications focusing on robotics education. Two escape rooms have been designed and are described with secondary school and tertiary target audiences, respectively. The puzzles are designed to teach concepts related to odometry, kinematics, and robot perception.

This paper is organised as follows: Section 2 uses the escapED framework to discuss the design and implementation of the activities in terms of what they entail, the narrative elements used, and how the escape rooms were run. In Section 3 the puzzles are presented with example solutions and intended learning outcomes. Section 4 presents and analyses the survey results and data analytics from the activities. Finally, Section 5, reflects on the lessons learnt, and suggests modifications that could be made to the activities to improve learning outcomes and playability.

2. Methodology

Two robotics-focused EERs were developed to engage students in and reinforce robotics concepts. The first activity (ER1) was targeted at high school students (ages 13–16). ER1 progresses with a theme in which participants need to locate some disaster recovery robots based on sensor, odometry, and kinematics data within a collapsing building so they can be safely recovered. ER1 assumes fundamental mathematical concepts around geometry and trigonometry.

The second activity (ER2) was targeted at undergraduate students studying robotics. ER2 progresses through a theme of recovering an exploratory robot on Mars that has been stolen by hackers using concepts related to odometry, forward kinematics, and inverse kinematics. ER2 is designed as a revision activity to follow modules in which the concepts of odometry and kinematics are explicitly taught.

We use the escapED framework formulated by Clarke et al. to describe and highlight the different elements within the escape room and how the escape room was conducted [27]. Our alignment with the escapED framework is described in Table 1 and Table 2 for each of our respective activities.

Table 1.

ER1 (high school) evaluation against escapED framework.

Table 2.

ER2 (Undergraduate robotics) evaluation of escapED framework.

Having provided a high-level evaluation of the design structures using the escapED framework, we highlight key relevant elements and follow this by providing extracts from each of the puzzles (in Section 3) to demonstrate how they should each be solved.

Although there are several different escape room validation techniques (websites, combination locks, etc.), our implementation uses an electronic decoder box [16,25]. These decoder boxes (Figure 1) provide a more immersive and less abstract experience than using a PC or tablet whilst facilitating timekeeping, data analytics, automated clue delivery, and validation of solutions. This less abstracted (non-screen) approach reduces the leap required in suspension of disbelief—a key element required to enjoy the game element of escape rooms [11,16]. The automated clue delivery operated by revealing one new digit of the code every 5 min, whilst never revealing the last digit. As the electronic decoder box uses a numeric keypad interface, all solutions need to be a number between 1 and 8 digits in length.

Figure 1.

Electronic decoder box used for solution validation, timekeeping, clue delivery, and analytics.

Participants were allowed the freedom to select their own groups, with each group sitting around a shared table. Pens were provided, and during the pre-game briefing, participants were informed that they were allowed to write on the puzzles (which made them easier to solve and helped with communication). Anonymous post-activity surveys were conducted to gauge participants’ feedback in relation to puzzle difficulty, enjoyment motivation, flow, and teamwork. In addition, analytics data related to puzzle completion time and incorrect guesses was recorded for each team. Institutional human ethics approval was approved under application HEC19459.

3. Puzzle Design

Each of the escape room activities consisted of three puzzles. These puzzles were each clustered around similar themes (field robotics) and were primarily paper-based and supplemented with physical props. The puzzles were provided to students one at a time in three separate sealed envelopes. The puzzle design was presented in terms of three elements: materials provided for the puzzle; the problem that needed to be solved; and how an example key could be assembled as a solution to each problem.

3.1. ER1: Puzzle 1: Odometry

3.1.1. Materials

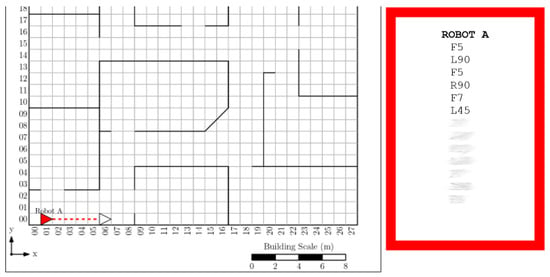

Note (storyline), building floor-plan (Figure 2), 2x robot odometry logs.

Figure 2.

Partial view of floor-plan and one of the robot logs for ER1 Puzzle 1. Red triangle is robot initial position, white triangle is robot position after first move.

3.1.2. Problem

Participants must use the robot floor-plan and the odometry logs to work out the current position of each of the two robots. The narrative explains that F relates to how far forward the robot drives and L/R refer to the angle to the left/right the robot has rotated.

3.1.3. Example Key

The key consists of the robot grid reference for each of the two robots in the form XXYY where the top-right square would be encoded as 2718.

3.2. ER1: Puzzle 2: Forward Kinematics

3.2.1. Materials

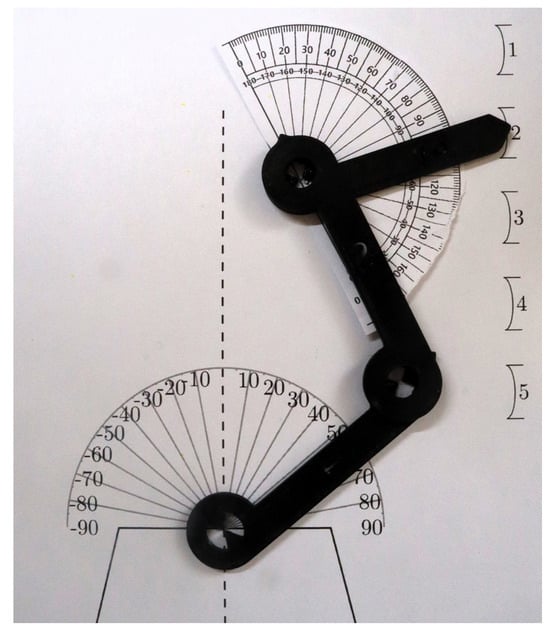

Note (storyline), 3D-printed armatures (Figure 3), Protractor, table of angles, robot angle instructions, and 2D robot profile with target buttons.

Figure 3.

Elements for Puzzle 2 with 3D-printed robot arms positioned with angles 50°, −75° and 97°(the first of multiple provided arm configurations).

3.2.2. Problem

Participants need to orient the robot arm using the provided protractors to a series of tuples of joint angles for joints 1, 2 and 3.

3.2.3. Example Key

The key consists of the button that is pointed to by the robotic arm after alignment according to each tuple of joint angles to decode different floors’ robots accessed on an elevator.

3.3. ER1: Puzzle 3: Sensors

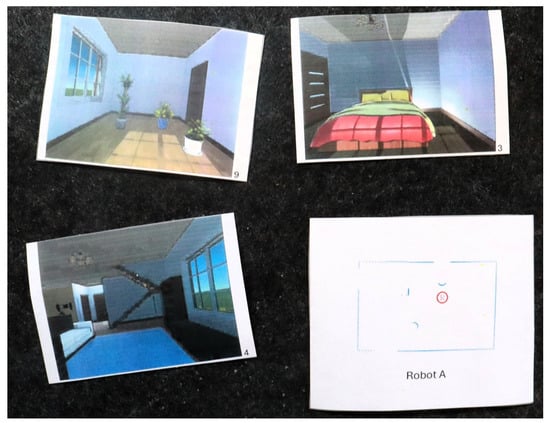

3.3.1. Materials

Note (storyline), 5x 2D lidar plots, 9x pictures of rooms (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Elements for Puzzle 3 which involves matching 2D LIDAR plots to different rooms.

3.3.2. Problem

Participants need to match each of the five LIDAR plots (labelled A–F) with one of the 9 rooms.

3.3.3. Example Key

The rooms are labelled 1–9 and the robot LIDAR plots are labelled A–E. Here, the LIDAR plot from robot A matches room 9, so the first digit is 9.

3.4. ER2: Puzzle 1: Odometry

3.4.1. Materials

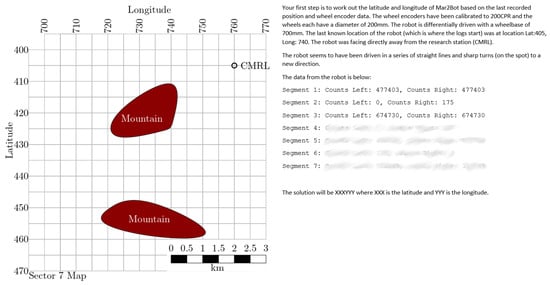

Figure 5.

Robot odometry log and map for ER2, Puzzle 1.

3.4.2. Problem

Participants must perform computations to convert the wheel encoder counts to the distance travelled for each wheel to account for rotations and distance travelled. The participants can then plot the robot movement and find the final resting place for the robot.

3.4.3. Example Key

The key consists of the final robot position with three digits for latitude and three digits for longitude.

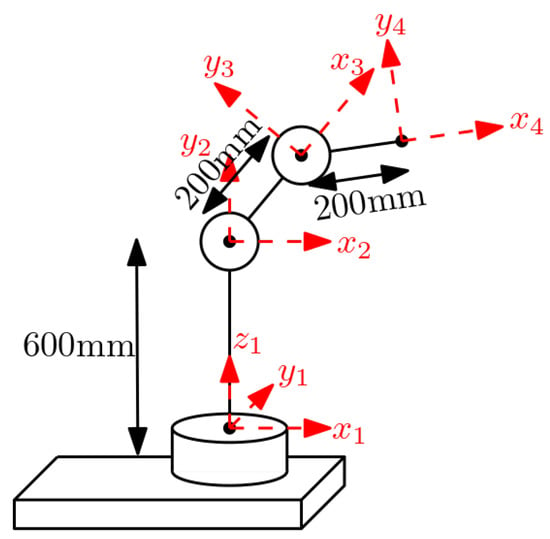

3.5. ER2: Puzzle 2: Forward Kinematics

3.5.1. Materials

Note (storyline), robot kinematic diagram (Figure 6), table of joint angles, the Denavit–Hartenberg parameters for the end effector, and a picture of a numeric keypad (similar to that used on the decoder box in Figure 1).

Figure 6.

Robot kinematic diagram for ER2, Puzzle 2 to allow kinematic positioning of the end effector to press certain digits on a keypad.

3.5.2. Problem

The arm on the robot was used to remotely push buttons on a keypad to open a secure facility. Participants need to work out the code by mapping 3D the position of the robot end effector to the different buttons on the numeric keypad.

3.5.3. Example Key

The key consists of the numbers that the robot end effector has pressed in order based on the kinematic logs (e.g., pressing the three buttons along the top of a keypad would render 123).

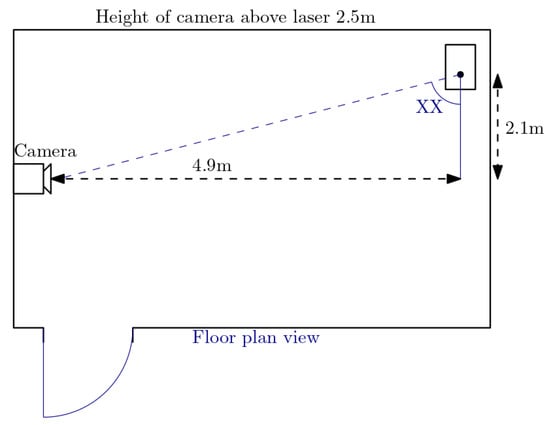

3.6. ER3: Puzzle 3: Inverse Kinematics

3.6.1. Materials

Note (storyline), room layout (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Room layout for ER2, Puzzle 3 which requires simple geometric inverse kinematics in three dimensions.

3.6.2. Problem

Participants need to work out the angles the robot needs to direct its onboard laser to disable the security camera.

3.6.3. Example Key

The angle for the laser is specified with two digits for the lateral rotation and two digits for the elevation of the laser to hit the camera (XXZZ).

4. Results and Evaluation

The following sub-sections describe and evaluate results from each of the two escape rooms based on data analytics and post-activity surveys.

4.1. Escape Room 1 Results

The activities were evaluated at several different levels and with several different groups of participants. Firstly, three groups of Alpha testers (10 players in total) were used to identify any typographical issues and ensure the puzzles were possible to solve. Eight of these Alpha testers were robotics domain experts (with PhDs in robotics field), while two of these Alpha testers were seasoned game-players who have completed numerous ERs and EERs. In addition to minor typographical changes, significant changes were made to puzzle 1 in relation to use of non-right angles and in the provided hardware for puzzle 2 (flatter protractors and clip-together 3D-printed mechanisms).

Following this, the escape rooms were trialled with engineering undergraduate students in a 4th-year robotics design subject. This activity was tested with six groups (19 participants) and a post-activity survey was used to gauge user acceptance (Table 3). An optional post-activity survey was provided where participants ranked their enjoyment of each puzzle on a scale of ‘very not fun’ (1) to ‘very fun’ (5) and then ranked each puzzle by difficulty on a scale of ‘very difficult’ (1) to ‘very easy’ (5). The final part of the survey was in Likert form with elements to gauge participants’ interest, engagement, and flow throughout the activity, with answers ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ (1) through to ‘strongly agree’. The intent for this escape room is not to make the puzzles all very hard or very easy, but assess the relative difficulty of the puzzles and learner performance for each of the puzzles. Analytics data, in terms of the time taken for each puzzle and the number of incorrect guesses, is summarised in Table 4. The analytics data was automatically and anonymously recorded by the electronic decoder box.

Table 3.

Post-activity survey results (ER1).

Table 4.

Analytics results (ER1).

Across the six Beta testing groups, only three groups successfully completed all the puzzles within the 45 min time-frame, which suggests that the level of difficulty will be too high for the target audience (high school students), as we would be aiming for a 90% completion rate with significantly less initial training. The results indicate that Puzzle 3 was the fastest to solve, although this result is misleading, as no time results are recorded for this puzzle from the three groups who did not complete the activity within the time interval. The decoder box allowed for programmed penalties, and so a 1 min time penalty was assigned for incorrect guesses (to dissuade guessing). Across the puzzles, an average of 4.8 incorrect guesses were made, though one group completed the whole activity and did not make any incorrect guesses.

Given that Puzzle 1 has the longest average completion time and the largest standard deviation, this would be the most reasonable point at which to reduce the puzzle’s difficulty or provide additional scaffolding. Students rated this puzzle with the lowest level of difficulty, which suggests that, conceptually, the puzzle is not too difficult, though the steps and any errors made along the way take up a significant amount of time. Reducing the path the robot operates over and removing the non-right-angle rotations would likely significantly reduce the time taken to solve this puzzle. One other avenue for potential improvement would be to include two sets of 3D-printed arms and paper for Puzzle 2. This way, for groups of 3–4 students, multiple configurations could be tested in parallel.

Despite the relative difficulty at least half the groups had with the escape room (in terms of failing to complete it (and hence, according to the storyline, having their robots lost forever under rubble), the participants really enjoyed all of the puzzles (Q1, Q2, and Q3). They also saw significant value in this activity in engaging high school students (Q8), and this aspect received the strongest positive response in the survey. Question 7 and 11 were both subject to strong positive feedback from students relating to motivation to complete and motivation to keep moving forward with each puzzle. It is possible that this could be enhanced further if some groups did not get stuck on the first puzzle for quite so long and were able to make more progress earlier on.

Question 9 is used to help gauge flow, and although it received a less positive response than the other questions (which is quite normal in a classroom environment), it still showed a very high level of positive response, demonstrating that most students were strongly focusing their attention on the activity. Finally, Question 10 shows a positive response relating to group feedback, suggesting that the game approach within the provided groups was well received by students.

4.2. Escape Room 2 Results

The second robotics educational escape room was first Alpha tested by an academic with a background in robotics to ensure the puzzles made sense and were solvable. This testing resulted in minor modifications to improve readability and formatting.

The puzzles were then evaluated by six groups of 4th-year undergraduate students who had recently been studying concepts related to kinematics and robot navigation. Students completed the puzzles within small groups of 3–4 and had a total of 60 min to complete each activity. A post-activity survey was filled out by the participants, with a change in Question 8 to reflect the different purposes of the activity; the results are presented in Table 5. Analytics from each of the decoder boxes are presented in Table 6.

Table 5.

Post-activity survey results (ER2).

Table 6.

Analytics results (ER2).

ER2 is significantly more difficult in ER1, as it is aimed at a higher-level audience (undergraduate vs. high school) and requires significantly more domain knowledge (computation of D-H Parameters and wheel encoder data). Lecture notes were permitted for the activity and more time was provided to participants (60 min for ER2 vs. 45 min for ER1). The puzzles for ER2 are more mathematical in nature, whereas for ER1 they are more conceptual in nature with minimal computation.

Although students indicated that, overall, they enjoyed each of the puzzles for ER2, Puzzle 2, which involved performing 3D forward kinematics, was rated the least enjoyable (although only slightly) and by far the most difficult (Table 5). The difficulty associated with this puzzle led to 40% of the teams being unable to complete the escape room, and supervising staff noted that those who completed it successfully relied heavily on the in-game clues (automatically provided every 5 min). All puzzles remained quite enjoyable despite significant differences in difficulty. The puzzle with the highest level of student enjoyment (Puzzle 3) also had the most incorrect guesses, which may demonstrate that participants’ learned from mistakes in a way that was rewarding and enjoyable.

The students indicated that the activity engendered high levels of intrinsic motivation (Q7 and Q11), which broadly aligns with other studies indicating increased student motivation and engagement. Students also indicated that they judged the activity to be a good fit for the subject, as it followed instructions related to odometry by 4 weeks and instruction related to kinematics by 2 weeks. Students also indicated that they enjoyed playing the game with others (Q10). Finally, Q9 related to students’ perception of flow, indicating the degree to which students blocked out their outside environment as they were so focused on the task at hand. Many students seemed to experience at least some level of flow, although it is possible that this could be further enhanced by making the activity more immersive (e.g., adding background music and props).

4.3. Comparative Analysis

It would be preferred if the overall success rate of the two activities could be improved so that more students could reach the end of the activity, solving all the problems whilst not heavily relying on the 5 min clues. There are several ways this could be achieved, including increasing the play time (which is currently 1 h), providing elements of partly solved puzzles to steer students in the correct direction, adding scaffolding, or decreasing the level of difficulty or game-induced confusion of one or more puzzles. In particular, the students seemed to struggle with the forward kinematics puzzles, and so reducing the 3D puzzle to a 2D puzzle and reducing the number of buttons for ER1-Puzzle2 could make the activities more achievable whilst still allowing them to practice the key concepts related to forward kinematics. Additional pre-game and in-game scaffolding could be provided to further enable students to successfully progress through the puzzles.

Participant feedback was encouragingly high across all of the trials, despite the relatively low success rate. Given that this is a review of Beta testing, the sample sizes are fairly small (29 participants for ER1 and 22 participants for ER2) but they do reflect positive results which should be further improved as the escape room puzzles are refined. Further testing for both sets of escape rooms with different cohorts would be useful, and should integrate aspects of pre/post quizzes, control groups and focus groups.

Some of the student feedback suggested that rewards (such as chocolate) should be included for successful completion of the activity (or for the winning team). Some authors strongly discourage the use of rewards, as games should be fun without the need for an incentive such as a reward, and adding a reward system may cause players to become goal-focused and skip elements (e.g., those involving a combination lock to get to the reward) [13]. The decoder box approach, with built-in penalties, tends to dissuade guessing, and so the latter concern is less relevant in this context. We consider that further research could be conducted with regard to adding rewards to an EER that is actually fun (rather than trying to make it fun at a price)—particularly if it can be integrated in a thematic way.

5. Conclusions

This study describes and evaluates two different educational escape rooms used to provide an active learning experience related to field robotics concepts. Post-activity surveys indicated that participants’ intrinsic motivation, engagement, and satisfaction were really high, even when they were faced with a significantly high level of difficulty. The educational escape room format provides a good scope of peer interactions and collaborative problem-solving while providing some level of flow for the majority of participants.

Based on participants’ feedback, a number of modifications will be made, including improving the clarity of images for the LIDAR puzzle, improving the provided hardware for the non-computational kinematics puzzles, and reducing the degrees of freedom for the computational kinematics puzzle. These modifications should ensure success for a greater cross-section of future participants whilst resulting in less reliance on in-game clues.

We are optimistic that modified versions of these activities will encourage students to study robotics and related STEM fields through a fun, engaging learning experience. Going beyond predominately paper-based EER problem-solving, we see significant potential for some escape room activities that incorporate actual human–robot interaction, possibly using forms of teleoperation, impedance learning, or haptic control [32].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.R. and M.F.; methodology, R.R. and M.F.; validation, R.R.; formal analysis, R.R.; investigation, R.R.; resources, R.R.; data curation, R.R.; writing—original draft preparation, R.R. and M.F.; visualization, M.F.; funding acquisition, R.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank our test participants (staff and students) from Bristol Robotics Laboratory, La Trobe University, and Escape Room Education, who have helped improve the puzzles’ quality, clarity and solvability.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hagele, M. Double-digit growth highlights a boom in robotics [industrial activities]. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2017, 24, 12–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, K.; Shiomi, M.; Kanda, T.; Hagita, N. Are robots appropriate for troublesome and communicative tasks in a city environment? IEEE Trans. Auton. Ment. Dev. 2011, 4, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makedon, V.; Mykhailenko, O.; Vazov, R. Dominants and Features of Growth of the World Market of Robotics. Eur. J. Manag. Issues 2021, 29, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digilina, O.; Teslenko, I. The robotics market: Development prerequisites, features and prospects. In Proceedings of the SHS Web of Conferences, EDP Sciences, Zilina, Slovakia, 13–14 October 2021; Volume 101, p. 02029. [Google Scholar]

- García-Morales, V.J.; Garrido-Moreno, A.; Martín-Rojas, R. The transformation of higher education after the COVID disruption: Emerging challenges in an online learning scenario. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 616059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coleman, T.E.; Money, A.G. Student-centred digital game–based learning: A conceptual framework and survey of the state of the art. High. Educ. 2020, 79, 415–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, J.; Ringer, A.; Saville, K.; Parris, M.A.; Kashi, K. Students’ motivation and engagement in higher education: The importance of attitude to online learning. High. Educ. 2022, 83, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Grant, W.J. A good story well told: Storytelling components that impact science video popularity on YouTube. Front. Commun. 2020, 5, 581349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillinghast, R.C.; Appel, D.C.; Winsor, C.; Mansouri, M. STEM outreach: A literature review and definition. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Integrated STEM Education Conference (ISEC), Princeton, NJ, USA, 1 August 2020; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, S. Peeking Behind the Locked Door: A Survey of Escape Room Facilities. 2015. Available online: https://scottnicholson.com/pubs/erfacwhite.pdf (accessed on 29 August 2025).

- Wiemker, M.; Elumir, E.; Clare, A. Escape room games. Game Based Learn. 2015, 55, 55–75. [Google Scholar]

- Veldkamp, A.; van de Grint, L.; Knippels, M.C.P.; van Joolingen, W.R. Escape education: A systematic review on escape rooms in education. Educ. Res. Rev. 2020, 31, 100364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, S.; Cable, L. Unlocking the Potential of Puzzle-Based Learning: Designing Escape Rooms and Games for the Classroom; Sage Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fotaris, P.; Mastoras, T. Escape rooms for learning: A systematic review. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Games Based Learning, Odense, Denmark, 3–4 October 2019; pp. 235–243. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, S. Creating engaging escape rooms for the classroom. Child. Educ. 2018, 94, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, R. Design of an open-source decoder for educational escape rooms. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 145777–145783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lathwesen, C.; Belova, N. Escape rooms in STEM teaching and Learning—Prospective field or declining trend? A literature review. Educ. Sci. 2021, 11, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yllana-Prieto, F.; González-Gómez, D.; Jeong, J.S. The escape room and breakout as an aid to learning STEM contents in primary schools: An examination of the development of pre-service teachers in Spain. Education 3-13 2023, 53, 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Pernas, S.; Gordillo, A.; Barra, E.; Quemada, J. Examining the use of an educational escape room for teaching programming in a higher education setting. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 31723–31737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avargil, S.; Shwartz, G.; Zemel, Y. Educational escape room: Break Dalton’s code and escape! J. Chem. Educ. 2021, 98, 2313–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, R.; Bennett, A. Increasing engagement with engineering escape rooms. IEEE Trans. Games 2020, 14, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guckian, J.; Eveson, L.; May, H. The great escape? The rise of the escape room in medical education. Future Healthc. J. 2020, 7, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decusatis, C.; Gormanly, B.; Alvarico, E.; Dirahoui, O.; McDonough, J.; Sprague, B.; Maloney, M.; Avitable, D.; Mah, B. A cybersecurity awareness escape room using gamification design principles. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 12th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC), Virtual, 26–29 January 2022; pp. 0765–0770. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, N.; Darby, W.; Coronel, H. An escape room as a simulation teaching strategy. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2019, 30, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, R.; Hall, R. Tabletop Escape Room Activities for Engaging Outreach in Engineering—A Preliminary Approach. IEEE Trans. Games 2023, 16, 331–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Pernas, S.; Gordillo, A.; Barra, E.; Quemada, J. Escapp: A web platform for conducting educational escape rooms. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 38062–38077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, S.; Peel, D.; Arnab, S.; Morini, L.; Keegan, H.; Wood, O. EscapED: A framework for creating educational escape rooms and interactive games to for higher/further education. Int. J. Serious Games 2017, 4, 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guigon, G.; Humeau, J.; Vermeulen, M. A model to design learning escape games: SEGAM. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Computer Supported Education, Funchal, Madeira, Portugal, 15–17 March 2018; pp. 191–197. [Google Scholar]

- Dittman, J.M.; Amendola, M.F.; Ramraj, R.; Haynes, S.; Lange, P. The COMET framework: A novel approach to design an escape room workshop for interprofessional objectives. J. Interprof. Care 2022, 36, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eukel, H.; Morrell, B. Ensuring educational escape-room success: The process of designing, piloting, evaluating, redesigning, and re-evaluating educational escape rooms. Simul. Gaming 2021, 52, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fotaris, P.; Mastoras, T. Room2Educ8: A framework for creating educational escape rooms based on design thinking principles. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Burdet, E.; Si, W.; Yang, C.; Li, Y. Impedance learning for human-guided robots in contact with unknown environments. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2023, 39, 3705–3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).