COVID-19: What We Have Learnt and Where Are We Going?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Update on Recent Variants

3. Current Management Practices

Therapies for COVID-19

4. Clinical Trials Related to COVID-19

5. Conclusions

6. Future Perspectives and Challenges

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Iacopetta, D.; Ceramella, J.; Catalano, A.; Saturnino, C.; Pellegrino, M.; Mariconda, A.; Longo, P.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Aquaro, S. COVID-19 at a Glance: An Up-to-Date Overview on Variants, Drug Design and Therapies. Viruses 2022, 14, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

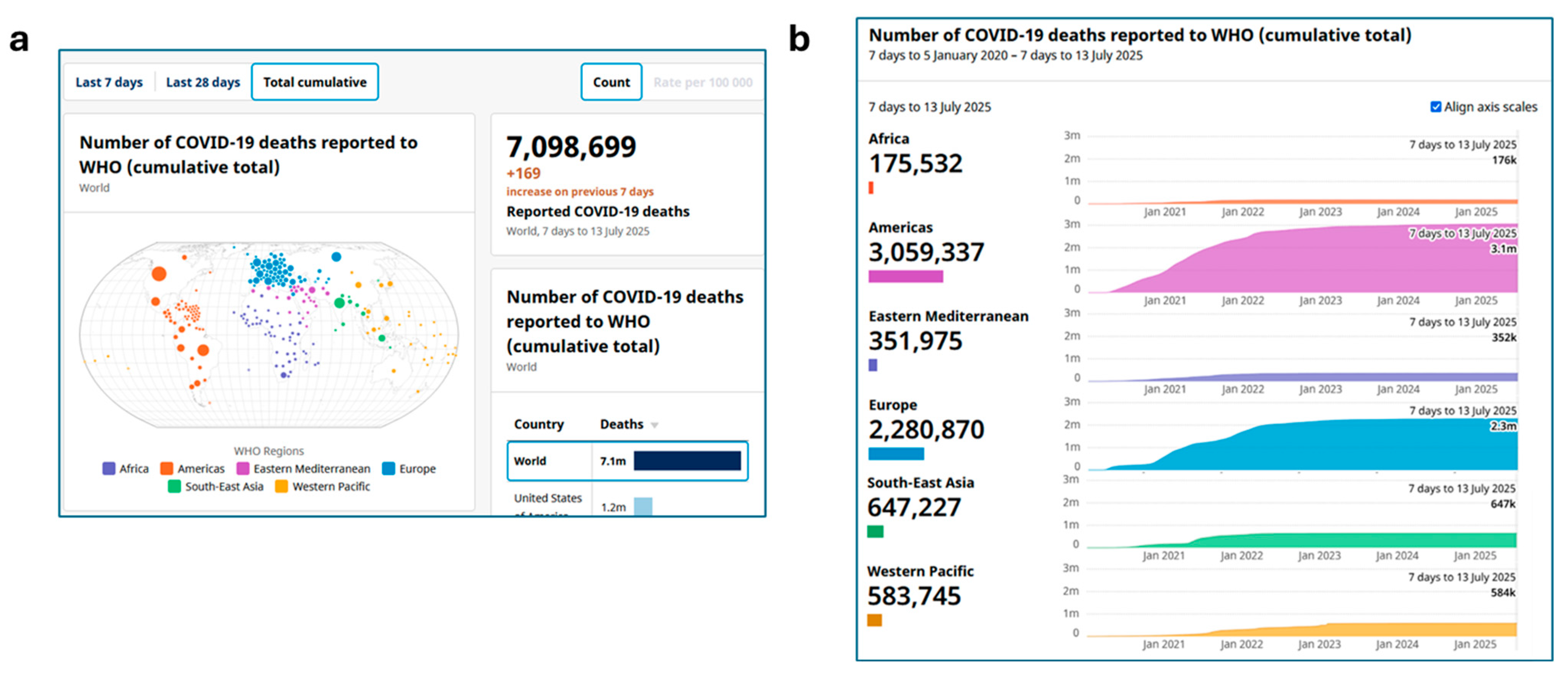

- WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online: http://covid19.who.int (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Anjos, J.R.C.D.; Correia, I.M.; de Moraes, C.A.L.C.; Cordeiro, J.F.C.; Trapé, A.A.; Mota, J.; Lopes Macado, D.R.; Santos, A.P.D. Sedentary Behavior, Physical Inactivity, and the Prevalence of Hypertension, Diabetes, and Obesity During COVID-19 in Brazil. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacopetta, D.; Catalano, A.; Ceramella, J.; Pellegrino, M.; Marra, M.; Scali, E.; Sinicropi, M.; Aquaro, S. The Ongoing Impact of COVID-19 on Pediatric Obesity. Pediatr. Rep. 2024, 16, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, A.; Iacopetta, D.; Ceramella, J.; Pellegrino, M.; Giuzio, F.; Marra, M.; Rosano, C.; Saturnino, C.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Aquaro, S. Antibiotic-Resistant ESKAPE Pathogens and COVID-19: The Pandemic beyond the Pandemic. Viruses 2023, 15, 1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Number of COVID-19 Deaths Reported to WHO (Cumulative Total). Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/deaths?n=c (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Chen, Z.; Xu, J.; Li, C.; Su, J.; Bian, Y.; Kim, H.; Lu, J. COVID-19 Drugs: A Critical Review of Physicochemical Properties and Removal Methods in Water. J. Environ. Chem. Engineer. 2025, 13, 115310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, A. COVID-19―Where Are We Now. Curr. Med. Chem. 2025, 32, 7188–7192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, A.; Ghosh Roy, S.; Dwivedi, R.; Tripathi, P.; Kumar, K.; Nambiar, S.M.; Pathak, R. Beyond the Pandemic Era: Recent Advances and Efficacy of SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines Against Emerging Variants of Concern. Vaccines 2025, 13, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulova, S.M.; Veselkina, U.S.; Astrakhantseva, I.V. Adaptation of the Vaccine Prophylaxis Strategy to Variants of the SARS-CoV-2 Virus. Vaccines 2025, 13, 761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Available online: https://www.who.int/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Vandelli, V.; Palandri, L.; Coratza, P.; Rizzi, C.; Ghinoi, A.; Righi, E.; Soldati, M. Conditioning Factors in the Spreading of COVID-19—Does Geography Matter? Heliyon 2024, 10, e25810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palandri, L.; Rizzi, C.; Vandelli, V.; Filippini, T.; Ghinoi, A.; Carrozzi, G.; De Girolamo, G.; Morlini, I.; Coratza, P.; Giovannetti, E.; et al. Environmental, Climatic, Socio-Economic Factors and Non-pharmacological Interventions: A Comprehensive Four-Domain Risk Assessment of COVID-19 Hospitalization and Death in Northern Italy. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2025, 263, 114471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

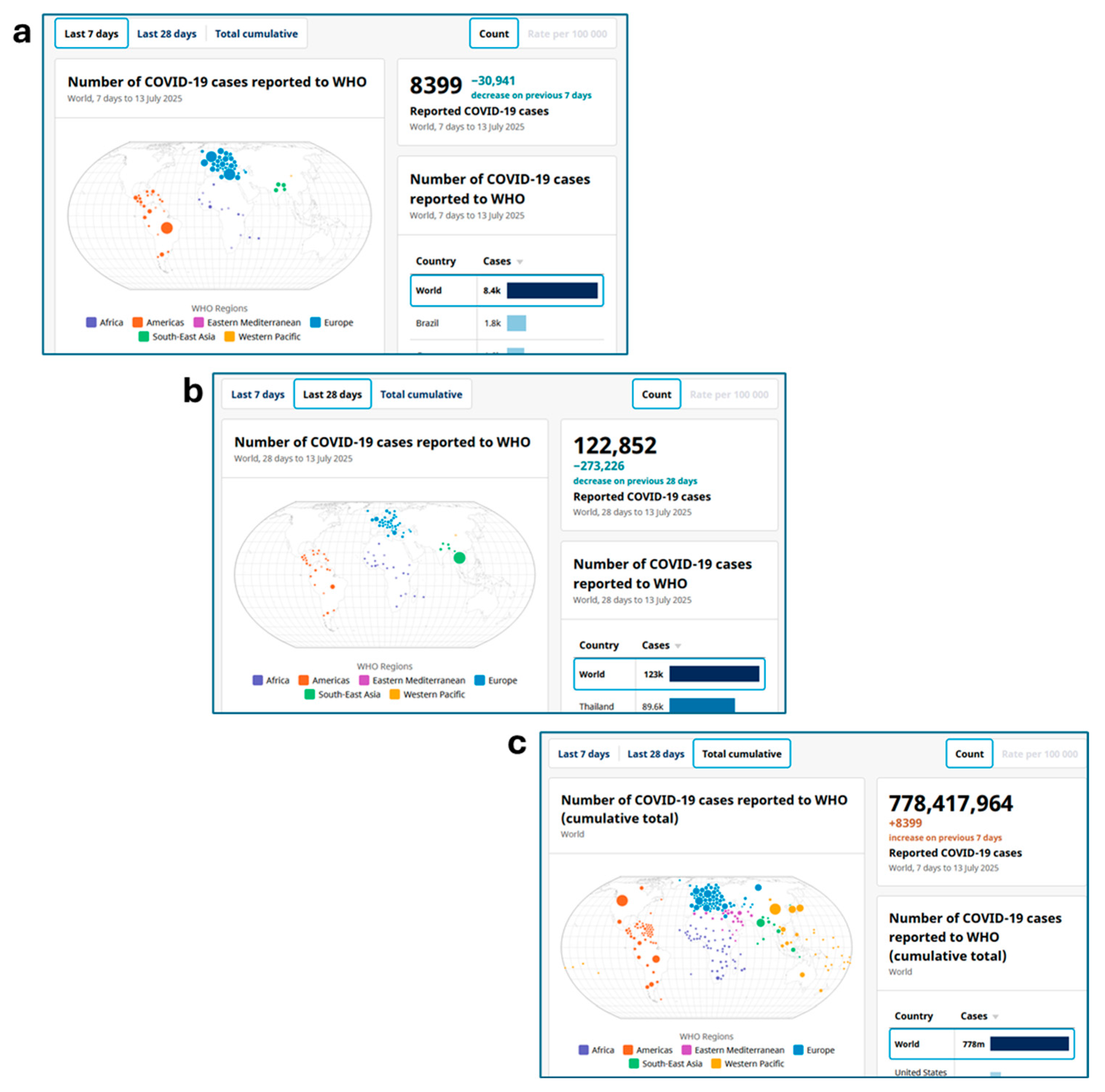

- COVID-19 Cases, World. Available online: https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?n=o (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Guo, C.; Yu, Y.; Liu, J.; Jian, F.; Yang, S.; Song, W.; Yu, L.; Shao, F.; Cao, Y. Antigenic and Virological Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 Variants BA.3.2, XFG, and NB.1.8.1. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, e374–e377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wehbe, R.; Khoshman, N.; Ousseily, Z.; Al-Tameemi, S.A.; Majzoub, R.E.; Najar, M.; Merimi, M.; Fayyad-Kazan, H.; Badran, B.; Fayyad-Kazan, M. Emerging SARS-CoV-2 Variants: Genomic Shifts, Immune Evasion, and Therapeutic Perspectives. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2025, 52, 886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y. Has Adaptive Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 Hit a Ceiling? Preprint 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branda, F.; Ciccozzi, M.; Scarpa, F. Genome-based Analyses of SARS-CoV-2 NB.1.8.1 Variant Reveals its Low Potential. Infect. Dis. 2025, 57, 805–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.T.; Islam, M.R.; Das, S.R.; Dey, B.R.; Siddiqui, T.H.; Mubarak, M. Emerging SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Subvariants in 2025: Clinical Impacts and Public Health Challenges. J. Biosci. 2025, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh. New COVID-19 Variants Detected in Bangladesh, no Major Cause for Alarm Yet. June 2025. Available online: https://www.icddrb.org/news/new-covid-19-variants-detected-in-bangladesh-no-major-cause-for-alarm-yet-09-06-2025 (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Mellis, I.A.; Wu, M.; Hong, H.; Tzang, C.C.; Bowen, A.; Wang, Q.; Gherasim, C.; Pierce, V.M.; Shah, J.G.; Purpura, L.J.; et al. Antibody Evasion and Receptor Binding of SARS-CoV-2 LP. 8.1. 1, NB. 1.8. 1, XFG, and Related Subvariants. bioRxiv 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern as of 29 August 2025. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/covid-19/variants-concern (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Aljabali, A.A.; Lundstrom, K.; Hromić-Jahjefendić, A.; Abd El-Baky, N.; Nawn, D.; Hassan, S.S.; Rubio-Casillas, A.; Redwan, E.M.; Uversky, V.N. The XEC Variant: Genomic Evolution, Immune Evasion, and Public Health Implications. Viruses 2025, 17, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angius, F.; Puxeddu, S.; Zaimi, S.; Canton, S.; Nematollahzadeh, S.; Pibiri, A.; Delogu, I.; Alvisi, G.; Moi, M.L.; Manzin, A. SARS-CoV-2 Evolution: Implications for Diagnosis, Treatment, Vaccine Effectiveness and Development. Vaccines 2024, 13, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, R. What to Know About XEC, the New SARS-CoV-2 Variant Expected to Dominate Winter’s COVID-19 Wave. JAMA 2024, 332, 1961–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaku, Y.; Yo, M.S.; Tolentino, J.E.; Uriu, K.; Okumura, K.; Ito, J.; Sato, K. Virological Characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 KP. 3, LB. 1, and KP. 2.3 Variants. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, e482–e483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; He, X.; Shi, H.; He, C.; Lei, H.; He, H.; Yang, L.; Wang, W.; Shen, G.; Yang, J.; et al. Recombinant XBB.1.5 Boosters Induce Robust Neutralization against KP.2- and KP.3-included JN.1 Sublineages. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2025, 10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LP.8.1 Lineage Report. Available online: https://outbreak.info/situation-reports?xmin=2025-01-31&xmax=2025-07-31&loc&pango=LP.8.1&selected (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Risk Evaluation for SARS-CoV-2 Variant Under Monitoring: NB.1.8.1. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/risk-evaluation-for-sars-cov-2-variant-under-monitoring-nb.1.8.1 (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Yi, B. Evaluation of the Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variant and the Spreading of LP.8.1 and NB. 1.8.1. medRxiv 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobar, O.; Cobar, S. Lo que se Conoce de XFG y XFG. 3, las Nuevas Variantes del SARS-CoV-2. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=it&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Lo+que+se+conoce+de+XFG+y+XFG.+3%2C+las+Nuevas+Variantes+del+SARS-CoV-2&btnG= (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- UK Warns of Rapid Spread of Frankenstein Strain ‘Stratus’ Covid Variant with Unusual Symptom. Available online: https://www.kurdistan24.net/en/story/849947/uk-warns-of-rapid-spread-of-frankenstein-strain-stratus-covid-variant-with-unusual-symptom?__cf_chl_tk=BX9psJiQR_D7IFhN8zaiypSjpnbDhc_9pY.LGHTo3b4-1753816132-1.0.1.1-K10YImDbNw5T8TAZsNVyXa3Z3dfEWdQq2O9WUleiy.A (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Risk Evaluation for SARS-CoV-2 Variant Under Monitoring: XFG. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/risk-evaluation-for-sars-cov-2-variant-under-monitoring-xfg (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- Ceramella, J.; Iacopetta, D.; Sinicropi, M.S.; Andreu, I.; Mariconda, A.; Saturnino, C.; Giuzio, F.; Longo, P.; Aquaro, S.; Catalano, A. Drugs for COVID-19: An Update. Molecules 2022, 27, 8562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mia, M.E.; Howlader, M.; Akter, F.; Hossain, M.M. Preclinical and Clinical Investigations of Potential Drugs and Vaccines for COVID-19 Therapy: A Comprehensive Review with Recent Update. Clin. Pathol. 2024, 17, 2632010X241263054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, J.F.; Yuan, S.; Chu, H.; Sridhar, S.; Yuen, K.Y. COVID-19 Drug Discovery and Treatment Options. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aadil, K.R.; Bhange, K.; Mishra, G.; Sahu, A.; Sharma, S.; Pandey, N.; Mishra, Y.K.; Kaushik, A.; Kumar, R. Nanotechnology Assisted Strategies to Tackle COVID and Long-COVID. BioNanoScience 2025, 15, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawazi, S.M.; Fathima, N.; Mahmood, S.; Al-Mahmood, S.M.A. Antiviral Therapy for COVID-19 Virus: A Narrative Review and Bibliometric Analysis. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2024, 85, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakti, A.S.; Susanti, I.; Kusumo, D.W. Narrative Review of Anti-Retrovirals Used in COVID-19 Treatment. J. Clin. Pharm. Pharmacol. Sci. 2024, 3, 36–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, M.D.; Warren, S.G. A Tale of Two Drugs: Molnupiravir and Paxlovid. Mutat. Res. Rev. Mutat. Res. 2025, 795, 108533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, D.K.; Gurijala, A.R.; Huang, L.; Hussain, A.A.; Lingan, A.L.; Pembridge, O.G.; Ratangee, B.A.; Sealy, T.T.; Vallone, K.T.; Clements, T.P. A Guide to COVID-19 Antiviral Therapeutics: A Summary and Perspective of the Antiviral Weapons against SARS-CoV-2 Infection. FEBS J. 2024, 291, 1632–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yousefbeigi, S.; Marsusi, F. Advanced Computational Approaches to Evaluate the Potential of New-Generation Adamantane-Based Drugs as Viroporin Inhibitors: A Case Study on SARS-CoV-2. J. Phys. Chem. B 2025, 129, 8127–8143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Xie, Y.; Hu, T.; Shen, J. Discovery and Development of VV116: A Novel Oral Nucleoside Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Drug. In Trends in Antiviral Drug Development; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 389–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakagawa, Y.; Kawaguchi, Y.; Hirose, H.; Hashiguchi, T.; Lee, J.; Hotta, A.; Kawamoto, J.; Sasaki, M.; Sawa, H.; Futaki, S. SARS-CoV-2 Inhibition through mRNA Delivery Using Engineered Extracellular Vesicles Displaying the Spike Protein. Biomaterials 2026, 325, 123594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahendran, T.R.; Cynthia, B.; Thevendran, R.; Maheswaran, S. Prospects of Innovative Therapeutics in Combating the COVID-19 Pandemic. Mol. Biotechnol. 2025, 67, 2598–2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, S.; Mukherjee, M.; Das, R. Pharmacological Strategies and Investigational Drugs for Emerging and Re-Emerging Diseases of Viral Origin. In Emerging and Re-Emerging Viral Diseases; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; pp. 113–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.A.; Singh, I.; Farid, A.; Wani, A.W.; Khanday, F.; Wani, A.K.; Shah, N.; Hassan, A.; Kabrah, A.; Qusty, N.F.; et al. Repositioning Antivirals Against COVID-19: Synthetic Pathways, Mechanisms, and Therapeutic Insights. Microb. Pathog. 2025, 206, 107724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satyam, S.M.; El-Tanani, M.; Patni, M.A.; Rehman, A.; Wali, A.F.; Rangraze, I.R.; Babiker, R.; Rabbani, S.A.; El-Tanani, Y.; Rizzo, M. Repurposing Anthelmintic Drugs for COVID-19 Treatment: A Comprehensive Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials on Ivermectin and Mebendazole. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latarissa, I.R.; Khairinisa, M.A.; Iftinan, G.N.; Meiliana, A.; Sormin, I.P.; Barliana, M.I.; Lestari, K. Efficacy and Safety of Antimalarial as Repurposing Drug for COVID-19 Following Retraction of Chloroquine and Hydroxychloroquine. Clin. Pharmacol. Adv. Appl. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, W.H.K.; Mukaka, M.; Callery, J.J.; Llewelyn, M.J.; Cruz, C.V.; Dhorda, M.; Ngernseng, T.; Waithira, N.; Ekkapongpisit, M.; Watson, J.A.; et al. Evaluation of Hydroxychloroquine or Chloroquine for the Prevention of COVID-19 (COPCOV): A Double-blind, Randomised, Placebo-Controlled Trial. PLoS Med. 2024, 21, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibrahim, S.; Siemieniuk, R.A.; Oliveros, M.J.; Islam, N.; Martinez, J.P.D.; Izcovich, A.; Qasim, N.; Zhao, Y.; Zaror, C.; Yao, L.; et al. Drug Treatments for Mild or Moderate Covid-19: Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. BMJ 2025, 389, e081165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caliman-Sturdza, O.A.; Soldanescu, I.; Gheorghita, R.E. SARS-CoV-2 Pneumonia: Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Therapeutics and COVID-19: Living Guideline. 10 November 2023. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/373975/WHO-2019-nCoV-therapeutics-2023.2-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Balkrishna, A.; Kumar, B.; Haldar, S.; Varshney, A. Looking beyond the Roots: Exploring the Untapped Potential of Withania somnifera. In Ashwagandha; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; pp. 354–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, A.; Iacopetta, D.; Ceramella, J.; Maio, A.C.; Basile, G.; Giuzio, F.; Bonomo, M.G.; Aquaro, S.; Walsh, T.J.; Sinicropi, M.S.; et al. Are Nutraceuticals Effective in COVID-19 and Post-COVID Prevention and Treatment? Foods 2022, 11, 2884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karunarathna, S.C.; Lu, W.; Patabedige, N.; Zhao, C.L.; Hapuarachchi, K.K. Unlocking the Therapeutic Potential of Edible Mushrooms: Ganoderma and their Secondary Metabolites as Novel Antiviral Agents for Combating COVID-19. N. Z. J. Bot. 2025, 63, 2470–2528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Worafi, Y.M. Evidence-Based Complementary, Alternative and Integrated Medicine and Efficacy and Safety: COVID. In Handbook of Complementary, Alternative, and Integrative Medicine; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025; pp. 271–291. [Google Scholar]

- Tavakoli, Z.; Ranjbar, F.; Tackallou, S.H.; Ranjbar, B. Nanostructures for the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of COVID-19: A Review. Part. Syst. Charact. 2025, 42, 2400083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Diak, I.L.; Swank, K.; McCartan, K.; Beganovic, M.; Kidd, J.; Gada, N.; Kapoor, R.; Wolf, L.; Kangas, L.; Wyeth, J.; et al. The Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) Drug Safety Surveillance during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Drug Saf. 2023, 46, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesko, B.; Deng, A.; Chan, J.D.; Neme, S.; Dhanireddy, S.; Jain, R. Safety and Tolerability of Paxlovid (Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir) in High Risk Patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, 2049–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.-M.; Chung, J.K.; Tamanna, S.; Bang, M.-S.; Tariq, M.; Lee, Y.M.; Seo, J.-W.; Kim, D.Y.; Yun, N.R.; Seo, J.; et al. Comparable Efficacy of Lopinavir/Ritonavir and Remdesivir in Reducing Viral Load and Shedding Duration in Patients with COVID-19. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yotsuyanagi, H.; Ohmagari, N.; Doi, Y.; Yamato, M.; Bac, N.H.; Cha, B.K.; Imamura, T.; Sonoyama, T.; Ichihashi, G.; Sanaki, T.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of 5-Day Oral Ensitrelvir for Patients With Mild to Moderate COVID-19. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2354991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syed, Y.Y. Ensitrelvir fumaric acid: First approval. Drugs 2024, 84, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xocova® (Ensitrelvir Fumaric Acid) Tablets 125 mg Approved in Japan for the Treatment of SARS-CoV-2 Infection, Under the Emergency Regulatory Approval System|News|Shionogi Co., Ltd. Available online: https://www.shionogi.com/global/en/news/2022/11/e20221122.html (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- FDA Approves Veklury Remdesivir for COVID 19 Treatment in Patients With Severe Renal Impairment Including Those on Dialysis. Available online: https://www.gilead.com/news/news-details/2023/fda-approves-veklury-remdesivir-for-covid-19-treatment-in-patients-with-severe-renal-impairment-including-those-on-dialysis (accessed on 8 April 2025).

- El-Fattah, M.H.A.; Sharaf, Y.A.; El-Sayed, H.M.; Hassan, S.A. Eco-friendly spectrofluorimetric determination of remdesivir in the presence of its metabolite in human plasma for therapeutic monitoring in COVID-19 patients. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 20251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsica, G.; Messina, E.; Bagaglio, S.; Galli, L.; Lolatto, R.; Sampaolo, M.; Barakat, M.; Israel, R.J.; Castagna, A.; Clementi, N. Clinico-Virological Outcomes and Mutational Profile of SARS-CoV-2 in Adults Treated with Ribavirin Aerosol for COVID-19 Pneumonia. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.C.; Hsieh, C.C.; Ko, W.C. Molnupiravir—A Novel Oral Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Agent. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhimraj, A. Pharmacologic Treatment and Management of Coronavirus Disease 2019. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2025, 39, 275–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Dai, X.; Ling, Y.; Wu, L.; Tang, L.; Peng, C.; Huang, C.; Liu, H.; Lu, H.; Shen, X.; et al. Oral VV116 versus Placebo in Patients with Mild-To-Moderate COVID-19 in China: A Multicentre, Double-Blind, Phase 3, Randomised Controlled Study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogbuagu, O.; Goldman, J.D.; Gottlieb, R.L.; Singh, U.; Shinkai, M.; Acloque, G.; Fusco, D.N.; Gonzalez, E.; Kumar, P.; Luetkemeyer, A.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Obeldesivir in Low-risk, Non-hospitalised Patients with COVID-19 (OAKTREE): A Phase 3, Randomised, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streinu-Cercel, A.; Castagna, A.; Chang, S.C.; Chen, Y.S.; Koullias, Y.; Mozaffarian, A.; Hyland, R.H.; Humeniuk, R.; Caro, L.; Davies, S.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Obeldesivir in High-Risk Nonhospitalized Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (BIRCH): A Phase 3, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barghash, R.F.; Gemmati, D.; Awad, A.M.; Elbakry, M.M.; Tisato, V.; Awad, K.; Singh, A.V. Navigating the COVID-19 Therapeutic Landscape: Unveiling Novel Perspectives on FDA-Approved Medications, Vaccination Targets, and Emerging Novel Strategies. Molecules 2024, 29, 5564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoushtari, M.H.; Raji, H.; Borsi, S.H.; Tavakol, H.; Cheraghian, B.; Moeinpour, M. Evaluating the Therapeutic Effect of Sofosbuvir in Outpatients with COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial Study. Galen Med. J. 2024, 13, e3035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Nair, R.; Huang, R.; Zhu, H.; Anderson, A.; Belen, O.; Tran, V.; Chiu, R.; Higgins, K.; Chen, J.; et al. Using Machine Learning to Determine a Suitable Patient Population for Anakinra for the Treatment of COVID-19 under the Emergency Use Authorization. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2024, 115, 890–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Food and Drug Administration. Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for Kineret (Anakinra) for Unapproved Use of an Approved Product Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/163546/download?attachment (accessed on 9 September 2025).

- Viermyr, H.K.; Tonby, K.; Ponzi, E.; Trouillet-Assant, S.; Poissy, J.; Arribas, J.R.; Dyon-Tafani, V.; Bouscambert-Duchamp, M.; Assoumou, L.; Halvorsen, B.; et al. Safety of Baricitinib in Vaccinated Patients with Severe and Critical COVID-19 Sub Study of the Randomised Bari-SolidAct trial. eBioMedicine 2025, 111, 105511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinstein, J.; Jagan, N.; Lorthridge-Jackson, S.; Hamer-Maansson, J.E.; Squier, P. Ruxolitinib for Emergency Treatment of COVID-19–Associated Cytokine Storm: Findings From an Expanded Access Study. Clin. Respir. J. 2025, 19, e70050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Hilgenfeld, R.; Whitley, R.; De Clercq, E. Therapeutic Strategies for COVID-19: Progress and Lessons Learned. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2023, 22, 449–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kianpour, P.; Mourtami, R.; Sahab-Negah, S.; Panahi, Y.; Bayatani, B.; Qazivini, A.; Izadi, M.; Mojtahedzadeh, M.; Shahrami, B.; Hadadi, A.; et al. Clinical Evaluation of Umifenovir as a Potential Antiviral Therapy for COVID-19: A Multi-center, Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial. Oman Med. J. 2025, 40, e716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, D.; Zhang, Q.; Lu, X.; You, Q.; Wang, L. Global First-in-class Drugs Approved in 2023–2024: Breakthroughs and Insights. Innovation 2025, 6, 100801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanetta, C.; Gasperini, C.; Amato, M.P.; Centonze, D.; Gallo, P.; Patti, F.; Riva, A.; Filippi, M. Potential Use of the SARS-CoV-2 Monoclonal Antibody Sipavibart in People with Multiple sclerosis: Definition of Different Patient Archetypes from an Italian Expert Group Perspective. J. Neurol. 2025, 272, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawazi, S.M.; Khan, J.; Othman, N.; Alolayan, S.O.; Alahmadi, Y.M.; Al Thagfan, S.S.; Helmy, S.A.; Marzo, R.R. REGEN-COV and COVID-19, Update on the Drug Profile and FDA Status: A Mini-review and Bibliometric Study. J. Public Health Res. 2021, 10, 63–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shaughnessy, J. Letter of Authorization Eli Lilly Bebtelovimab Emergency Use Authorization; FDA: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Khorramnia, S.; Navidi, Z.; Sarkoohi, A.; Iravani, M.M.; Orandi, A.; Orandi, A.; Ghazi, S.F.; Fallah, E.; Malekabad, E.S.; Moghadam, S.H.P. Remdesivir versus Sotrovimab in Coronavirus Disease 2019: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Health Sci. Rep. 2025, 8, e71118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, A.; Gonzalez-Rojas, Y.; Juarez, E.; Crespo Casal, M.; Moya, J.; Rodrigues Falci, D.; Sarkis, E.; Solis, J.; Zheng, H.; Scott, N.; et al. Effect of Sotrovimab on Hospitalization or Death Among High-Risk Patients with Mild to Moderate COVID-19: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2022, 327, 1236–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Focosi, D.; Casadevall, A.; Franchini, M.; Maggi, F. Sotrovimab: A Review of Its Efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Viruses 2024, 16, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drugs@FDA: FDA-Approved Drugs. SUPPL 149. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/daf/index.cfm?event=overview.process&ApplNo=125276 (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Haars, J.; Wallin, F.; Elfving, K.; Jonsson, A.K.; Ellström, P.; Mölling, P.; Lindha, J.; Yinc, H.; Sundqvistd, M.; Kaden, R.; et al. Dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 Variants and Mutations in Central Sweden between 2023 and 2024 and their Potential Implications on Monoclonal Antibodies Pemivibart and Sipavibart as PrEP in the Region. Infect. Dis. 2025, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lievano, F.; Doan, T. Chapter 21—Vaccine Pharmacovigilance. In Pharmacovigilance: A Practical Approach, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2026; pp. 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Pezzullo, A.M.; Cristiano, A.; Boccia, S. Global Estimates of Lives and Life-Years Saved by COVID-19 Vaccination During 2020–2024. JAMA Health Forum 2025, 6, e252223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mambelli, F.; de Araujo, A.C.V.; Farias, J.P.; de Andrade, K.Q.; Ferreira, L.C.; Minoprio, P.; Leite, L.C.; Oliveira, S.C. An Update on Anti-COVID-19 Vaccines and the Challenges to Protect Against New SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Pathogens 2025, 14, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krammer, F. The Role of Vaccines in the COVID-19 Pandemic: What Have We Learned? Semin. Immunopathol. 2024, 45, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, S.; Qayyum, H.A.; Qayyum, I.A.; Khan, Z.; Islam, T.; Ahmed, N.; Hopkins, K.L.; Sommers, T.; Akhtar, S.; Khan, S.A.; et al. COVID-19 Vaccines Side Effects among the General Population during the Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1420291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Omoush, O.; Khalil, L.; Ramadan, A.; Tarakhan, H.; Alzoubi, A.; Nabil, A.; Hajali, M.; Abdelazeem, B.; Saleh, O. Sarcoidosis and COVID-19 Vaccines: A Systematic Review of Case Reports and Case Series. Rev. Med. Virol. 2025, 35, e70011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, V.; Makary, M.A. An Evidence-Based Approach to Covid-19 Vaccination. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 2484–2486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olesińska, W.; Biernatek, M.; Lachowicz-Wiśniewska, S.; Piątek, J. Systematic Review of the Impact of COVID-19 on Healthcare Systems and Society—The Role of Diagnostics and Nutrition in Pandemic Response. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catalano, A. COVID-19: Could Irisin Become the Handyman Myokine of the 21st Century? Coronaviruses 2020, 1, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Li, X.; He, T.; Ju, F.; Qiu, Y.; Tian, Z. Impact of Physical Activity on COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, N.; Mishra, S. Impact of Yoga on Immune Response with Special Reference to COVID-19: A Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. Curr. Tradit. Med. 2024, 10, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Focosi, D.; Franchini, M.; Maggi, F.; Shoham, S. COVID-19 Therapeutics. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2024, 37, e0011923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinicaltrials.gov (Expert Search). Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/expert-search (accessed on 31 July 2025).

| VUM | Name | Date of Collection of the Earliest Example or Detection of Lineage | Date of Assignation to VUMs [22] | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| XEC | 16 May 2024 | 24 September 2024 | [8,23,24,25] | |

| LB.1 | 26 February 2024 | 28 June 2024 | [26] | |

| KP.3 | 11 February 2024 | 3 May 2024 | [27] | |

| KP.3.1.1 | 27 March 2024 | 19 July 2024 | [18] | |

| LP.8.1 | 5 March 2025 | January 2025 | [28,29,30] | |

| NB1.8.1 | Nimbus | 22 January 2025 | 23 May 2025 | [18] |

| XFG | Stratus or Frankenstein | 27 January 2025 | 25 June 2025 | [31,32,33] |

| Name (Administration Route) | Category | Approval | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paxlovid (oral) | Ritonavir + nirmatrelvir (antivirals) | Approved by US FDA (Mild to moderate infection) | [40,61] |

| Kaletra® or Aluvia® (oral) | Ritonavir + lopinavir (antivirals) | Not authorized for COVID-19 treatment | [62] |

| Ensitrelvir (Xocova) (oral) | 3CL protease inhibitor (antiviral) | Approved in Japan (2022–2023); Singapore (2023) EUA by US FDA | [63,64,65] |

| Remdesivir (Veklury®) (IV) | Antiviral (nucleoside analog) | Infection with high risk to develop severe infection. Approved by US FDA | [66,67] |

| Ribavirin (Rebetol®) (oral) | Antiviral (prevents viral RNA synthesis and mRNA capping) | Not authorized for COVID-19 treatment | [68] |

| Favipiravir or T-705 (Avigan®) (oral) | Antiviral (nucleoside analog) | Not authorized for COVID-19 treatment | [69] |

| Molnupiravir (Lagevrio) (oral) | Antiviral (nucleoside analog) | Mild to moderate infection EUA by US FDA | [40,70] |

| Mindeudesivir (VV116 or JT001) (oral) | Antiviral (nucleoside analog) | Not authorized for COVID-19 treatment Mild to moderate infection | [71] |

| Obeldesivir (GS-5245 or ATV006) (oral) | Antiviral (nucleoside analog) | Phase 3 clinical studies | [72,73] |

| Sofosbuvir (oral) | Antiviral (nucleoside analog) | Not approved by FDA for COVID-19 Phase 3 clinical studies | [74,75] |

| Galidesivir (BCX4430 or Immucillin-A) (IM, IV) | Antiviral (nucleoside analog) | Not approved by FDA for COVID-19 | [35] |

| Anakinra (Kineret) (IV) | Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist | Not approved by FDA for COVID-19 EUA by US FDA | [76,77] |

| Baricitinib (Olumiant) (oral) | Anti-inflammatory: Janus kinase (JAK1/JAK2) inhibitor | Not approved by FDA for COVID-19 | [78] |

| Ruxolitinib (oral) | Anti-inflammatory: Selective Janus kinase [JAK]1/JAK2 inhibitor | Phase 3 (for emergency treatment of COVID-19-associated cytokine storm in patients eligible for hospitalization) | [79] |

| Sabizabulin (oral) | Anticancer: Microtubule inhibitor | Phase 3 trial (≈408 patients) | [80] |

| Umifenovir, brand-name Arbidol (oral) | Antiviral: Fusion inhibitor | Not authorized for COVID-19 treatment | [81] |

| Leritrelvir (RAY1216) | Antiviral: SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitor | Not authorized for COVID-19 treatment | [82] |

| Evusheld (IM) | anti-Spike monoclonal antibodies: tixagevimab and cilgavimab | Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) | [41,83] |

| Regen-CoV (Ronapreve®) (IV, SC) | IgG1j monoclonal antibodies: casirivimab and imdevimab | Not authorized for COVID-19 treatment (mild-to-moderate infection) | [84] |

| Bebtelovimab (LY-CoV1404) (IV) | Human IgG1 monoclonal antibody | Not authorized for COVID-19 treatment (mild-to-moderate infection) | [85] |

| Sotrovimab (VIR-7831 or GSK4182136) (Xevudy®) (IV, IM) | IgG1j monoclonal antibody | Not authorized for COVID-19 treatment (mild-to-moderate infection) US EUA phase 2 clinical trial | [86,87,88] |

| Tocilizumab (Actemra) (IV) | IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibody | US FDA approved for hospitalized adults on systemic steroids and oxygen/ventilatory support. WHO-recommended for severe/critical cases. | [89] |

| Pemivibart (Pemgarda™/VYD222) (IV) | Monoclonal antibody | Not authorized for COVID-19 treatment EUA FDA | [90] |

| Name of the Clinical Trial | Topic of the Study | NCT Number (Status) | Completion Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| A Study to Learn About the Study Medicine Paxlovid (Nirmatrelvir + Ritonavir) in Adults Aged 60 and Older Living in Korean Long-term Care Hospitals Who Have COVID-19 | Antivirals (Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir) | NCT07089680 (Recruiting) | 30 November 2025 (Estimated) |

| A Study to Learn About Effects of Living With COVID-19 and the Use of the Medicines Nirmatrelvir-Ritonavir in Treating COVID-19 | Antivirals (Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir) | NCT06085924 (Recruiting) | 31 December 2025 (Estimated) |

| Study Understanding Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis of Novel Antibodies (SUPERNOVA) Sub-study | mAb (Sipavibart) | NCT05648110 (Completed) | 11 February 2025 |

| A Study to Learn About the Study Medicine Ibuzatrelvir in Adults With COVID-19 Who Are Severely Immunocompromised | Antiviral (Ibuzatrelvir) | NCT07013474 (Recruiting) | 6 May 2027 (Estimated) |

| Evaluation of Direct Antiviral Treatments Against SARS-CoV-2 in Immunocompromised Patients with COVID-19. A G2i Study, National Multicenter Observational and Retrospective from June 2023 to April 2024 (COVID) | Antivirals | NCT06683937 (Not yet recruiting) | 1 June 2025 (Estimated) |

| Finding Treatments for COVID-19: A Trial of Antiviral Pharmacodynamics in Early Symptomatic COVID-19 (PLATCOV) | Antivirals | NCT05041907 (Recruiting) | January 2027 (Estimated) |

| Efficacy of Colchicine in Improving Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Mild-to-Moderate COVID-19 Pneumonia in Lahore: A Randomized Control Trial (Colchicine) | Anti-inflammatory (Colchicine) | NCT06847204 (Recruiting) | 24 June 2025 (Estimated) |

| To Evaluate the Safety, Efficacy, and Pharmacokinetics of Orally Administered Prolectin-M | Gal-3 antagonist (Prolectin-M) | NCT05733780 (Not yet recruiting) | February 2024 (Estimated) |

| A Study on the Effects in Healthy People of a New Drug Called PDI204 for Treating COVID-19 (PHONIC) | Human IgG mAb (PDI204) | NCT06965751 (Not yet recruiting) | 31 December 2025 (Estimated) |

| A Study of the Efficacy of Troxerutin in Preventing Thrombotic Events in COVID-19 Patients | Bioflavonoid (Troxerutin) | NCT06355258 (Recruiting) | March 2025 (Estimated) |

| Efficacy and Safety of Nitazoxanide 600 Mg in the Outpatient Treatment of COVID-19 and Influenza | Antiparasitic (Nitazoxanide) | NCT06817096 (Recruiting) | June 2027 (Estimated) |

| T Cell Therapy Opposing Novel COVID-19 Infection in Immunocompromised Patients (TONI) | Coronavirus-specific T cell (CST) | NCT05141058 (Recruiting) | 15 December 2027 (Estimated) |

| Name of the Clinical Trial | Topic of the Study | NCT Number (Status) | Completion Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| A Study of mRNA-1283 Injection Compared With mRNA-1273 Injection in Participants ≥12 Years of Age to Prevent COVID-19 (NextCOVE) | Vaccines | NCT05815498 (Completed) | 12 April 2025 |

| Open-label, Multi-center, Non-Inferiority Study of Safety and Immunogenicity of BIMERVAX for the Prevention of COVID-19 in Adolescents From 12 Years to Less Than 18 Years of Age | Vaccines | NCT06234956 (Recruiting) | 30 December 2024 (Estimated) |

| A Randomized Trial Evaluating a mRNA-VLP Vaccine’s Immunogenicity and Safety for COVID-19 (ARTEMIS-C) | Vaccines | NCT06147063 (Completed) | 27 March 2025 |

| A Trial of a Next Generation COVID-19 Vaccine Delivered by Inhaled Aerosol (AeroVax) | Vaccine delivery | NCT06381739 (Recruiting) | January 2027 (Estimated) |

| Study to Investigate the Immunogenicity, Reactogenicity, and Safety of mRNA-1083 Vaccine (SARS-CoV-2 [COVID-19] and Influenza) in Adults ≥50 Years of Age | Vaccines | NCT06694389 (Active, not recruiting) | 10 December 2025 (Estimated) |

| A Clinical Study to Investigate the Safety and Immunogenicity in Relation to Product Attributes of mRNA-1083 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 [SARS-CoV-2] and Influenza Vaccine) | Vaccines | NCT06508320 (Active, not recruiting) | 17 September 2025 (Estimated) |

| A Study to Assess Long-term Outcomes of Myocarditis Following Administration of COVID-19 mRNA Vaccine (SPIKEVAX) | Vaccines | NCT06189053 (Active, not recruiting) | 31 October 2028 (Estimated) |

| A Study on the Clinical Course, Outcomes, and Risk Factors of Myocarditis and Pericarditis After Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine | Vaccines | NCT06113692 (Active, not recruiting) | 30 June 2025 (Estimated) |

| Post-marketing Surveillance (PMS) Use-Result Surveillance with SPIKEVAX BIVALENT and SPIKEVAX X Injection | Vaccines | NCT06333704 (Recruiting) | 10 December 2028 (Estimated) |

| A Study to Investigate the Immunogenicity, Reactogenicity, and Safety of mRNA-1083 (Influenza and COVID-19) Vaccine in Adults ≥18 to <65 Years of Age | Vaccines | NCT06864143 (Recruiting) | 3 September 2025 (Estimated) |

| A Study to Evaluate the Safety and Immunogenicity of the mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines in Healthy Children Between 6 Months to Less than 6 Years of Age | Vaccines | NCT05436834 (Recruiting) | 27 October 2025 (Estimated) |

| A Study to Evaluate the Immunogenicity and Safety of mRNA-1283 COVID-19 Variant-containing Formulations | Vaccines | NCT07089706 (Recruiting) | 11 September 2025 (Estimated) |

| A Study to Learn About COVID-19 RNA-Based Variant-Adapted Vaccine Candidate(s) Against SARS-CoV-2 in Adults, Including Those at Higher Risk of Severe COVID-19 | Vaccines | NCT07069309 (Recruiting) | 6 January 2026 (Estimated) |

| A Study to Learn About How the Flu and COVID-19 Vaccines Act in Healthy People | Vaccines (in combination with flu vaccine) | NCT06821061 (Recruiting) | 22 December 2025 (Estimated) |

| Evaluation of COVID-19 Immune Barrier and Reinfection Risk (COVID) | Vaccines and reinfection | NCT05774093 (Recruiting) | 31 July 2027 (Estimated) |

| COVID-19: Early Detection of Worsening by Voice and Respiratory Pattern Characteristics (COVOICE) | Early Detection of COVID-19 | NCT05892549 (Recruiting) | July 2026 (Estimated) |

| A Study of Post COVID-19 Mechanisms for Chronic Lung Sequelae | Post COVID-19 | NCT06006884 (Recruiting) | August 2027 (Estimated) |

| Ensitrelvir for Viral Persistence and Inflammation in People Experiencing Long COVID (PREVAIL-LC) | Ensitrelvir in long-COVID patients | NCT06161688 (Active, not recruiting) | 31 December 2025 (Estimated) |

| Medical Herbs Inhibit Inflammation Directing T Cells to Kill the COVID-19 Virus (COVID) | Dietary Supplements | NCT04790240 (Recruiting) | 30 May 2027 (Estimated) |

| Breathing Techniques and Meditation for Health Care Workers During COVID-19 Pandemic | Breathing Techniques and Meditation | NCT04482647 (Active, not recruiting) | 30 April 2027 (Estimated) |

| Comparison of Cardiopulmonary Fitness Level with Normal Values After COVID-19 | Cardiopulmonary Fitness Level Study | NCT04753346 (Recruiting) | 1 January 2024 (Estimated) |

| CU-COMMITS: COVID-19 Care in Black and Latino Communities and Households. Clinical and Molecular Outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 | Long-term Outcomes of COVID-19 | NCT05467930 (Recruiting) | May 2027 (Estimated) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Hellenic Society for Microbiology. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Catalano, A. COVID-19: What We Have Learnt and Where Are We Going? Acta Microbiol. Hell. 2025, 70, 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/amh70040042

Catalano A. COVID-19: What We Have Learnt and Where Are We Going? Acta Microbiologica Hellenica. 2025; 70(4):42. https://doi.org/10.3390/amh70040042

Chicago/Turabian StyleCatalano, Alessia. 2025. "COVID-19: What We Have Learnt and Where Are We Going?" Acta Microbiologica Hellenica 70, no. 4: 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/amh70040042

APA StyleCatalano, A. (2025). COVID-19: What We Have Learnt and Where Are We Going? Acta Microbiologica Hellenica, 70(4), 42. https://doi.org/10.3390/amh70040042