Abstract

Background: Domestic refrigeration and egg handling are key factors in ensuring household food safety. Inadequate temperature control and poor hygiene in refrigerators can promote the survival and growth of foodborne pathogens. This study aimed to (i) characterize refrigerator temperature profiles and surface microbial contamination and (ii) screen eggs and egg-storage areas for the presence of Salmonella spp. and Campylobacter spp. Methods: Fifty domestic refrigerators were monitored twice in 2024 and 2025 in Porto, Portugal. The temperatures were continuously logged on the lowest shelf, which was swabbed for microbiological analysis. Surface hygiene was evaluated using total viable counts (TVC), Enterobacteriaceae, and Escherichia coli enumerated following ISO methods. Detection of pathogens Listeria monocytogenes, Salmonella spp., and Campylobacter spp. was performed using real-time PCR. Eggs (n = 92 in 2024; n = 88 in 2025), and domestic egg storage areas (total n = 76) were screened for Salmonella and Campylobacter. Results: The mean refrigerator temperatures were 6.0 ± 0.5 °C in 2024 and 6.1 ± 0.5 °C in 2025; 44% and 50% of the units, respectively, exceeded the recommended 6 °C threshold. In 2025, 31 (62%) and 33 (66%) refrigerators showed higher TVC and Enterobacteriaceae counts compared to 2024, whereas E. coli was only detected sporadically. L. monocytogenes, Salmonella spp., or Campylobacter spp. were not recovered from the refrigerator surfaces. Likewise, Salmonella and Campylobacter were not detected in any of the eggs or egg-storage sites. Indicator microorganism’s counts were not associated with the mean temperature. Conclusions: The absence of correlation between ΔT and Δ microbial counts suggests that behaviour-driven hygiene factors, rather than the relatively small year-to-year temperature differences observed, are more influential in determining household bioburden. Maintaining refrigerator temperatures ≤ 6 °C together with simple hygiene practices remains essential for reducing household food safety risks.

1. Introduction

Food safety is a cornerstone of public health, aiming to prevent foodborne illnesses that affect millions of people worldwide each year [1]. While significant attention has been given to primary production, processing, and distribution, the domestic environment remains a critical yet often underestimated stage in the food chain [2]. Household practices, including the storage of perishable foods, play a decisive role in determining the risk of microbial contamination and subsequent transmission to consumers [3].

Refrigerators are indispensable for extending the shelf life of perishable foods and limiting microbial growth [4]. However, inadequate temperature control, poor cleaning habits, and improper food storage can undermine their protective roles [5]. Surveys in several European countries have shown that a substantial proportion of domestic refrigerators operate above the Codex Alimentarius recommended threshold of 6 °C [6], often resulting in detectable microbial contamination of internal surfaces. Such conditions favour the survival and, in some cases, even the proliferation of foodborne pathogens, thereby amplifying the potential risks within households [7].

Among these pathogens, three are of particular concern: Listeria monocytogenes is psychrotrophic, capable of multiplying at refrigeration temperatures, and associated with severe illness and high mortality among vulnerable populations [8,9]. Salmonella spp. is one of the most frequent causes of foodborne outbreaks worldwide and can persist in a variety of foods and environments [10,11]. Campylobacter spp., despite being thermotolerant, survive long enough under refrigeration to cause infection and remain the leading bacterial cause of gastroenteritis globally [12,13]. Refrigeration prevents growth but does not eliminate Campylobacter; C. jejuni remained detectable after 7 days at 4 °C and even after 28 days at −20 °C in naturally contaminated broiler meat, underscoring persistence through the cold chain and into domestic storage [14].

Beyond the direct detection of pathogens, the enumeration of indicator microorganisms provides valuable insight into the overall hygiene status. Total viable counts at 30 °C reflect the general microbial load and cleaning effectiveness, whereas Enterobacteriaceae are indicative of possible fecal contamination and/or poor sanitation [15]. The detection of Escherichia coli serves as an even more specific indicator of recent fecal contamination and highlights the potential presence of enteric pathogens [16].

Eggs and egg-derived products are among the most common vehicles of Salmonella transmission worldwide, and their close association with poultry production makes them a relevant matrix for Campylobacter detection [17,18]. Evidence from domestic settings shows that Salmonella can be recovered from refrigerator surfaces, as demonstrated in a case–control study from the UK [19]. Moreover, Salmonella was found in 14% of egg storage compartments in a survey of 100 households in Belgrade [20]. These data justify the targeted monitoring of refrigerators as potential reservoirs that could compromise the safety of chilled storage. As both pathogens remain major agents of foodborne diseases, examining eggs together with refrigerator hygiene provides complementary insights into domestic microbiological risks.

Although domestic refrigerators and eggs have been studied separately in different contexts, most available data are cross-sectional, offering only a static view of microbial hazards. Longitudinal studies remain scarce, and in Portugal, there is a lack of integrated research addressing both household refrigeration practices and the microbiological status of eggs as potential vehicles of infection.

The present study addresses this gap through a two-year longitudinal investigation of domestic refrigerators and table eggs in Porto, Portugal. This study combined temperature monitoring, microbiological analysis of key pathogens and hygiene indicators, and a structured evaluation of household food safety practices. The study comprised two complementary components implemented within the same households: (i) sampling of domestic refrigerators to characterize temperature performance and surface hygiene, and (ii) microbiological screening of eggs and egg-holders and stored by consumers. These components were designed to capture different but interrelated aspects of domestic food safety behaviours. By integrating both storage environments and food matrices, the study provides a comprehensive overview of potential microbiological hazards and opportunities for risk reduction in domestic settings.

2. Materials and Methods

This longitudinal study was conducted between 2024 and 2025 to evaluate the hygiene conditions, operating temperatures, and microbiological status of domestic refrigerators. A total of 50 household refrigerators used exclusively for food storage were included in the study. Participants were recruited on a voluntary basis among residents of Porto, Portugal, without restrictions regarding age, sex, or educational background. Recruitment followed an open voluntary approach; households were not selected based on refrigerator model or characteristics, and no prioritization or ordering was applied. The selected households represented diverse demographic profiles, reflecting the real-world domestic conditions. Sampling was conducted in two campaigns approximately one year apart to enable the assessment of behavioural variations over time.

2.1. Sampling

Each participating household received a standardized sampling kit that was prepared under aseptic conditions. The kit included (i) a sterile polyurethane cloth (34 × 37 cm) pre-moistened with Neutralizing Rinse Solution (SodiBox, Nevez, France) for the bottom shelf surface sampling, which was selected as it typically represents the coldest and most contamination-prone area of the refrigerator; (ii) one sterile pair of disposable gloves to wear while sampling; (iii) one sterile swab in Neutralizing Rinse Solution (Liofilchem, Roseto degli Abruzzi, Italy) for sampling the egg holder area; (iv) a sealed plastic transport bag for sample storage; and (v) an RC-5 temperature data logger (Elitech, San Jose, CA, USA).

For collecting the eggs, the kit contained a small, insulated box with two compartments for the proper transport of two eggs. Each kit also included written instructions with step-by-step guidance and an illustrated diagram detailing the sampling procedures for the refrigerator surfaces and eggs.

A structured questionnaire was included in the sampling kit to collect information on household practices related to food storage, and hygiene. The questionnaire consisted of two sections that addressed different aspects of domestic food management. The first section examined the participants’ knowledge and behaviours related to refrigerator use. The questionnaire included questions concerning (i) awareness of temperature zones within the refrigerator, (ii) organization of foods according to these zones, (iii) separation of raw and cooked foods, (iv) removal of outer packaging (e.g., cardboard or plastic) prior to storage, and (v) refrigerator cleaning practices, including the cleaning method, frequency, and timing of the last cleaning. The second section focused on egg handling and storage. Participants were asked about (i) the origin of the eggs (own production, local farms, or commercial sources), (ii) brand and country of origin, and (iii) typical storage conditions (refrigerated or at room temperature).

2.2. Temperature Measurement

Temperature measurements were conducted in situ over an 8 h overnight period. An Elitech RC-5 data logger, included in the sampling kit and programmed to record at 15 min intervals, was placed on the bottom shelf of the refrigerator to capture the lowest expected temperatures.

2.3. Microbiological Analysis

2.3.1. Refrigerator Surfaces

Surface sampling using the sterile cloths provided to participants followed the procedures described in ISO 18593:2018 [21].

To the plastic bag containing the cloth, 225 mL of Buffer Peptone Water (BPW, Alliance Bio Expertise, Bruz, France) was added and homogenized in a homogenizer (Seward, West Sussex, UK) for 2 min.

The following assays were performed: total viable counts (TVC) following ISO 4833:2013 [22] by surface plating on Plate Count Agar (PCA; Liofilchem, Roseto degli Abruzzi, Italy); enumeration of Enterobacteriaceae according to ISO 21528-2:2017 [23] using Violet Red Bile Glucose Agar (VRBG, Liofilchem, Roseto degli Abruzzi, Italy); enumeration of beta-glucuronidase-positive Escherichia coli according to ISO 16649-1:2018 [24] using Tryptone Bile X-glucuronide Agar (TBX; Liofilchem, Roseto degli Abruzzi, Italy).

Campylobacter spp., L. monocytogenes, and Salmonella spp. were detected using real-time PCR. Briefly, 25 mL of BPW was transferred to 225 mL of Bolton broth (OXOID, Thermo Fisher, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) and homogenized for 2 min. The inoculated Bolton broths were incubated for 48 h at 41.5 ± 1 °C. Campylobacter spp. detection was performed as described by Barata et al. [25]. For L. monocytogenes, 25 mL of BPW was transferred to 225 mL of Half-Fraser broth (Bio-Rad, Marnes-la-Coquette, France) and homogenized for 2 min. The inoculated Half-Fraser broths were incubated for 24 h at 30 ± 1 °C. Listeria monocytogenes detection was performed using the commercial iQ-Check Listeria monocytogenes II PCR Detection Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For the detection of Salmonella spp., 25 mL of BPW was incubated for 24 h at 37 ± 1 °C. Salmonella spp. detection was performed using the commercial iQ-Check Salmonella spp. II PCR Detection Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. All analyses were performed within 24 h of sample collection. Real-time PCR runs were performed on a Bio-Rad CFX Opus 96 real-time PCR system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and data were acquired and analyzed using CFX Maestro software (Bio-Rad).

In case of positive results, confirmation results for Enterobacteriaceae followed ISO 21528-2:2017 [23], for Campylobacter spp. followed ISO 10272-2:2017 [26], for L. monocytogenes spp. followed ISO 11290-1:2017 [27] and for Salmonella spp. followed ISO 6579-1:2017 [28].

2.3.2. Eggs

Eggs were sampled as they were found in each household—whether stored in the refrigerator or at room temperature—to accurately reflect consumer practices. In Portugal, eggs are sold unwashed and their shells may naturally carry microorganisms. Although participants were instructed to collect the eggs as they stored them, we had no information on whether any of them washed the eggs before refrigeration. Domestic egg washing is considered a poor food-safety practice, as it can disperse microorganisms through splashing, remove the protective cuticle, and facilitate microbial penetration, thereby increasing the risk of cross-contamination to the egg-holder or other refrigerator surfaces. This uncertainty in handling practices may therefore introduce a potential source of pathogenic contamination.

The eggshell and internal contents were analyzed separately. For each egg, the surface of the shell was sampled using a sterile cotton swab and Neutralizing Rinse Solution. One swab was placed in 9 mL of BPW and the other was placed in 9 mL of Bolton broth. The internal contents (yolk and white) were homogenized, and each homogenate was inoculated into 90 mL of BPW broth and 90 mL of Bolton broth. Salmonella spp. and Campylobacter spp. were investigated using pre-enrichment procedures followed by real-time PCR detection, as previously described. All samples were processed within 24 h of collection.

2.3.3. Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed to examine whether cleaning product choice differed by age group and European Qualifications Framework (EQF) level using the chi-square test. The test was applied to contingency tables constructed from the frequency of responses in each category. A significance level of p < 0.05 was adopted to determine whether the differences between the groups were statistically significant. The same was performed for microbial contamination between refrigerators cleaned with detergent-based products and those cleaned with non-detergent methods

The 75th and 95th percentiles of the temperature distribution were calculated to assess the variability and upper extremes of the domestic refrigerator performance. The 75th percentile represents the temperature below which 75% of the recorded values are observed, whereas the 95th percentile denotes the temperature exceeded by only 5% of the refrigerators, thereby identifying extreme operating conditions that may pose a risk to food safety and hygiene.

To evaluate surface contamination, we applied the criteria defined by Düven et al. (2021) [29], with <5 CFU/cm2 (≈0.7 Log10) considered acceptable, 5–25 CFU/cm2 (0.7–1.4 Log10) borderline, and >25 CFU/cm2 (>1.4 Log10) unsatisfactory. To enable direct comparison with our results, which are expressed as CFU per cloth, the area-based limits were converted to CFU/cloth by approximating the sampled surface area. Based on measurements from a representative sample of domestic refrigerators in Portugal, a standard shelf area of approximately 1500 cm2 was assumed. Multiplying each value by this surface area resulted in the following operational limits for this study: <7.5 × 103 CFU/cloth (<3.88 Log10) classified as acceptable, 7.5 × 103–3.75 × 104 CFU/cloth (3.88–4.57 Log10) as borderline, and >3.75 × 104 CFU/cloth (>4.57 Log10) as unsatisfactory.

Data analysis focused on assessing the year-to-year correlations between temperature variation and microbial load. For each refrigerator, the change in mean temperature between 2024 and 2025 (ΔT)—defined as the difference in mean refrigerator temperature between the two sampling years (i.e., 2025 mean temperature minus 2024 mean temperature)—was calculated along with the corresponding change in surface counts (ΔLog10 CFU/cloth). These values were computed separately for total viable counts (TVC), Enterobacteriaceae, and E. coli, allowing the evaluation of whether temperature fluctuations were associated with variations in microbial indicators. For refrigerators in which bacterial counts could not be determined due to insufficient dilution, results were assigned the highest quantifiable value defined for this study (TVC: 6.36 Log10; Enterobacteriaceae: 6.18 Log10; E. coli: 4.18 Log10). In case of growth absence, a value of 1.00 Log10 CFU/cloth was assigned to enable statistical analysis.

The correlations between ΔT and Δ microbial counts were evaluated using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (ρ) [30,31], which measures the strength and direction of a monotonic association between two variables. The coefficient was calculated using the following equation:

where di is the difference between the ranks of each paired observation, and n is the total number of paired values. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, and p > 0.05 was interpreted as no statistically significant association.

3. Results

3.1. Participants Survey

All participants (100%) reported that they knew their refrigerator was divided into zones with different temperatures. Of these, 98% were aware that different types of food should be stored in specific areas. However, only 66% of respondents organized their food or prepared meals according to these zones to ensure proper preservation. Conversely, 34% of the respondents admitted to placing raw food on the same shelf as cooked food. Additionally, 64% of the participants stated that they usually removed double cardboard or plastic packaging from purchased products before storing them in the refrigerator.

Regarding cleaning practices, less than 1% of the participants reported using a mixture of detergent and lemon, followed by 4% who used lemon, bleach, or a combination of vinegar and bleach. Six percent used water only or a mixture of dish soap and vinegar, 10% used dish soap, 16% used a combination of detergent and vinegar, 20% relied solely on vinegar, and 24% used general-purpose cleaning detergents. It should be noted that mixing hypochlorite-based bleach with acidic cleaning products is hazardous because it can release chlorine gas. Such combinations should never be used without a thorough rinsing step between applications; nevertheless, this unsafe practice was reported by a small number of participants. In terms of cleaning frequency, less than 1% of the participants reported cleaning their refrigerator once or thrice per year, and 4% cleaned it every six months. Ten percent reported cleaning every two months, 14% every 15 days, and another 14% weekly. The majority (44%) cleaned their refrigerator monthly, while 8% stated that they cleaned it only when necessary.

The analysis of the data by age group revealed distinct patterns in cleaning preferences and product usage among the participants (Table 1). Among participants under 30 years of age, the majority (67%) reported using kitchen detergent, followed by water (22%) and vinegar (11%) for cleaning. This indicates a clear preference for commercial and ready-to-use cleaning products among this younger group. In the 31–50 age group, a similar trend was observed, with 80% using kitchen detergent, 15% opting for vinegar, and 5% using lemon. This suggests a consolidation of the use of industrial cleaning agents among working-age adults, likely because of their perceived efficiency and convenience. Participants aged 51–60 years demonstrated a more balanced distribution: 50% used kitchen detergent, 25% used water, and 25% used vinegar. This diversity in cleaning choices may reflect increased environmental awareness or a preference for natural cleaning alternatives. In contrast, the 61–70 age group showed a marked shift towards traditional and natural cleaning methods. The majority (58%) used vinegar (alone or in combination with detergent), while 17% used water and another 17% used kitchen detergent. A chi-square test of independence was conducted to examine the relationship between age group and type of cleaning product used. The associations between the variables were not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Although the results did not reach statistical significance, the data suggested a trend indicating that younger participants preferred commercial products (such as kitchen detergent), whereas older participants tended to use more natural agents, such as vinegar and water.

Table 1.

Distribution of cleaning product use by age group and EQF level among participants.

The analysis of cleaning practices according to the European Qualifications Framework (EQF) levels revealed notable differences in the types of cleaning products used by the participants. Participants with EQF level 2 showed a balanced preference between water (43%) and vinegar (43%), while a smaller proportion (14%) reported using kitchen detergents. This pattern suggests a greater reliance on natural and easily accessible cleaning agents among individuals with lower qualifications. At EQF level 4, cleaning practices were more diverse: water (20%), vinegar (30%), lemon (10%), kitchen detergent (30%), and vinegar combined with kitchen detergent (10%). This group appears to adopt a more mixed approach, combining both traditional and commercial cleaning products, possibly reflecting greater awareness of cleaning effectiveness and hygiene in this group. For participants with EQF level 6, the vast majority (76%) used kitchen detergent, while 21% used vinegar, and only 3% used water. This indicates a clear preference for commercial cleaning products among individuals with higher qualification levels, potentially linked to their perceptions of efficacy, convenience, and hygiene assurance. A chi-square test of independence was performed to examine the association between the EQF level and the type of cleaning product used. The results revealed a statistically significant relationship between these two variables (p < 0.05). Participants with lower qualification levels (EQF 2) predominantly used natural cleaning agents, such as water and vinegar, in equal proportions (43% each), whereas those at EQF level 4 showed a more balanced use of both natural and commercial products. In contrast, participants with higher qualification levels (EQF 6) primarily relied on kitchen detergent (76%), with considerably lower use of water (3%) and vinegar (21%). These findings indicate that educational or qualification level significantly influences cleaning product choice, suggesting that individuals with higher qualifications tend to favour commercial cleaning agents, possibly due to greater awareness of product efficacy, hygiene standards, and convenience. However, socioeconomic factors, such as household income, may also play a role, as individuals with lower educational levels often have more limited financial resources, which could influence their preference for more affordable alternatives, such as water and vinegar. The study did not evaluate the correct use of cleaning products, such as appropriate dilution or application practices.

A comparison of microbial contamination between refrigerators cleaned with detergent-based products (n = 26) and those cleaned with non-detergent methods (n = 20) showed no statistically significant differences in microbial contamination. The median values were similar between the two groups for TVC (4.70 vs. 4.95 Log10 CFU/cloth), and for Enterobacteriaceae (5.79 vs. 7.12 Log10 CFU/cloth).

In 2024, 48 of the 50 participants provided two eggs—one for Campylobacter spp. detection and one for Salmonella spp. detection—resulting in 96 samples. In 2025, 44 of the 50 participants provided two eggs each, resulting in 88 samples. In 2024, 44% of the eggs originated from home production and 56% from commercial establishments, and 73% (n = 37) of the participants reported storing eggs in the refrigerator. In 2025, 41% of the eggs originated from farms and 59% from commercial establishments, with 78% (n = 39) of the participants reporting refrigerator storage.

3.2. Temperature Measurement of Refrigerators

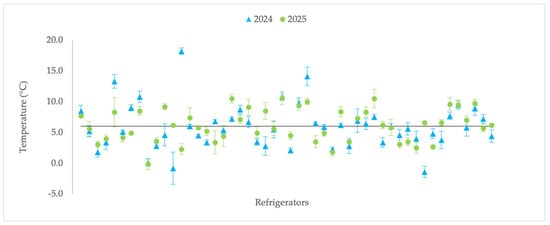

The average temperature of the 50 refrigerators monitored in 2024 was 6.0 ± 0.5 °C, ranging from −1.4 ± 1.2 °C to 18.2 ± 1.0 °C (Table 2). A total of 21 units (42%) recorded mean values above the recommended 6 °C (Figure 1). In 2025, the average temperature was 6.1 ± 0.5 °C, with a minimum of −0.1 ± 0.1 °C and a maximum of 10.6 ± 0.3 °C. 25 refrigerators (50%) exceeded the 6.0 °C threshold (Figure 1). Twenty-eight (56%) of the sampled refrigerators showed an increase in the mean temperature from 2024 to 2025.

Table 2.

Temperature profiles and surface counts for 50 domestic refrigerators sampled in 2024 and 2025.

Figure 1.

Temperature variation (°C) of 50 refrigerators sampled in 2024 (blue) and 2025 (green), with mean ± standard deviation.

3.3. Microbiological Analysis of Refrigerators Surface

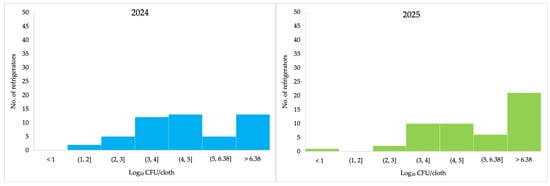

The minimum TVC was 1.43 Log10 CFU/cloth in 2024 and 2.64 Log10 CFU/cloth in 2025, while the maximum quantifiable counts were 6.20 and 6.36 Log10 CFU/cloth, respectively (Table 1). Thirty-one (62%) refrigerators had higher TVC in 2025 than those in 2024 (Table 2). In 2024, the highest proportion of TVC was observed in the category > 6.36 Log10 CFU/cloth, corresponding to 13 refrigerators. In 2025, most refrigerators also fell within this category, with 21 samples exceeding 6.36 Log10 CFU/cloth (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Total viable counts at 30 °C (Log10 CFU/cloth) for each sampled refrigerator in 2024 and 2025 following ISO 4833.

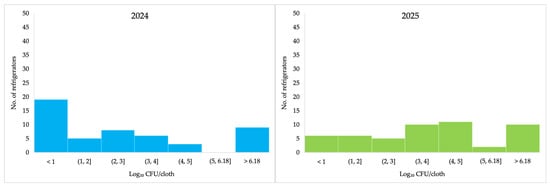

Thirty-three (66%) refrigerators showed an increase in Enterobacteriaceae counts in 2025 compared with 2024 (Table 2). The lowest values were 1.00 (2024) and 1.30 Log10 (2025), and highest quantifiable counts were 4.94 and 5.45 Log10, respectively (Table 2). In 2024, the highest proportion of Enterobacteriaceae counts was observed in the <1.00 Log10 CFU/cloth category, corresponding to 19 refrigerators. In 2025, most refrigerators (n = 11) fell within the 4.00–5.00 Log10 CFU/cloth range (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Enterobacteriaceae counts (log10 CFU/cloth) for each sampled refrigerator in 2024 and 2025 following ISO 21528-2.

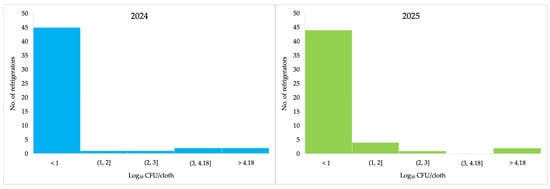

None of the refrigerators showed detectable E. coli counts in either of the two consecutive year (Table 2). The lowest counts obtained were 1.48 Log10 CFU/cloth in 2024 and 1.00 Log10 in 2025, while higher counts were 3.66 and 2.81 Log10, respectively (Table 2). In 2024 and 2025, the highest proportion of E. coli counts was observed in the <1.00 Log10 CFU/cloth category, comprising 44 and 45 refrigerators, respectively (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Results of enumeration of Escherichia coli (Log10 CFU/cloth) for each sampled refrigerator in 2024 and 2025 following ISO 16649-1.

Based on the TVC results, in 2024, 26% (n = 13) of the refrigerators were classified within the acceptable limit, 18% (n = 9) within the borderline range, and 56% (n = 28) as unsatisfactory. In 2025, the distribution shifted considerably: only 20% (n = 10) of refrigerators fell within the acceptable limit, 14% (n = 7) were borderline, and 66% (n = 33) were classified as unsatisfactory. This increase in the proportion of unsatisfactory units from 2024 to 2025 indicates a marked deterioration in overall hygiene status.

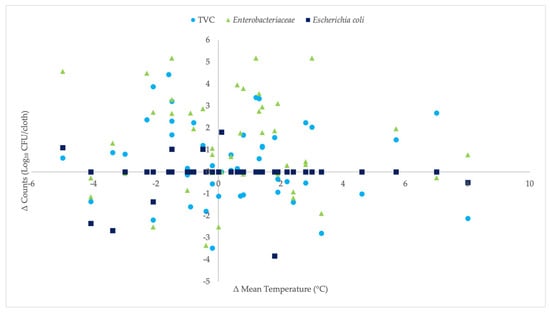

For each refrigerator, no statistically significant association was observed between year-to-year changes in mean temperature (ΔT, 2025–2024) and the corresponding changes in surface counts (ΔLog10 CFU/cloth): TVC, p = 0.382; Enterobacteriaceae, p = 0.794; and E. coli, p = 0.615 (Figure 5). In practical terms, this suggests that temperature alone accounts for little temporal variation in microbial indicators. Data from refrigerator no. 13 were excluded from the longitudinal analysis because the units monitored in 2024 and 2025 were different. After being notified that the 2024 temperature data indicated non-compliance with the recommended refrigerated storage conditions, the owner replaced the refrigerator.

Figure 5.

Relationship between changes in mean refrigerator temperature (ΔT, 2025–2024) and changes in surface counts (ΔLog10 CFU/cloth): TVC (●), Enterobacteriaceae (▲), and β-glucuronidase-positive E. coli (■).

Neither Campylobacter spp. nor Salmonella spp. were detected in the egg holder samples in 2024 (n = 37/50) or 2025 (n = 39/50). Likewise, all refrigerator surface samples (n = 100; 50 per year) were negative for Campylobacter spp., L. monocytogenes, and Salmonella spp.

3.4. Detection of Salmonella and Campylobacter in Eggs

None of the 92 eggs analyzed tested positive for Campylobacter spp. or Salmonella spp.

4. Discussion

This two-year household study provides a longitudinal perspective on refrigeration practices and surface hygiene under real-life conditions. Monitoring these pathogens in domestic refrigerators warrants attention, given that Campylobacteriosis is the most frequently reported zoonosis in the European Union and salmonellosis typically ranks second —highlighting the epidemiological importance of both [32].

Masson et al. (2017) [33] conducted an observational study in France to assess how consumers organized food items within domestic refrigerators under controlled laboratory conditions. Their findings are directly comparable to those of the present study: they reported that only 30% of participants removed external packaging before storage, particularly for products such as yoghurts and fresh vegetables. In our study, similar behaviours were observed, with most participants also retaining external packaging for several food categories, suggesting that this practice is common across different European populations. None of the participants demonstrated an understanding of the internal temperature gradient within the refrigerator. Most individuals arranged foods according to convenience and visibility rather than food safety criteria. Consequently, temperature-sensitive items such as raw meat, ready-to-eat salads, and fresh pasta were often stored in inappropriate zones, representing a potential risk of cross-contamination. Overall, a lack of awareness regarding cold zones (0–6 °C) was widespread among participants, even when visual indicators were present inside the appliance. Participants in the present study reported substantially greater awareness of refrigerator temperature zones and recommended storage practices compared with those observed by Masson et al. Overall, 100% of respondents recognized that refrigerators are divided into zones with different temperatures, and 98% acknowledged that specific foods should be stored accordingly. However, this awareness did not always translate into correct behaviour: only 66% organized their food items according to these zones, while 34% admitted placing raw and cooked foods on the same shelf. Moreover, 64% reported removing external cardboard or plastic packaging before storage, a markedly higher proportion than that described by Masson et al., (2017) [33].

Most participants in the present study (44%) reported cleaning their refrigerator monthly, while smaller proportions cleaned it every 15 days (14%), weekly (14%), or every two months (10%). Only a minority reported infrequent cleaning (4% biannually, <1% once or three times per year). These results suggest that most households perform refrigerator cleaning at relatively regular intervals. Similar findings were reported by Ovca et al. (2020) [34] in Slovenia, who observed that 38% of consumers cleaned their refrigerators monthly and 32% every 2–3 months, indicating that infrequent cleaning is a common household practice across European populations. The authors also found that cleaning frequency was associated with education level and perceived food safety risk, suggesting that behavioural rather than technical factors may drive hygiene-related routines. In line with these findings, the present study also revealed a significant association between educational level and cleaning behaviour. Participants with higher EQF levels predominantly used commercial cleaning agents such as kitchen detergent, whereas those with lower qualification levels more frequently relied on natural products such as water and vinegar. This pattern supports the hypothesis proposed by Ovca et al. (2020) [34] and Lagendijk et al. (2008) [3] in the United States, that cleaning-related practices are influenced more by behavioural and educational factors than by technical knowledge alone. The results suggest that higher educational attainment may be associated with a stronger perception of hygiene efficacy and food safety, leading to the use of industrial cleaning products, while lower educational levels are linked to simpler, more traditional cleaning methods. There is currently no EU-level public health guideline defining how frequently domestic refrigerators should be cleaned, and therefore the practices reported by participants cannot be evaluated against a formal standard.

The temperature distribution observed in this study aligns with previous Portuguese and European data. In Portugal, Azevedo et al. (2005) [35] reported that approximately 70% of domestic refrigerators operated above 6 °C, while Galvão et al. (2017) [36] and Dumitrașcu et al. (2020) [37] found mean temperatures close to 5–6 °C, with upper values frequently exceeding 8 °C. A recent European synthesis by Bonanno et al. (2024) [38] consolidated these national datasets, estimating the 75th percentile of Portuguese domestic refrigerator temperatures between 6 °C and 8 °C, and the 95th percentile around 10–12 °C. According to our results, the 75th percentile of refrigerator temperatures in Portuguese households was 8.3 °C and the 95th percentile 10.8 °C, values consistent with those previously reported for Portugal. This aligns with Bonanno et al. (2024) [38], who estimated 10 °C as the 95th percentile across European households, used to establish the shelf-life study temperatures [39].

Beyond temperature monitoring, the assessment of microbial contamination in refrigerators surfaces provided critical insight into household hygiene. Analyses focused on indicator microorganisms (total viable counts, Enterobacteriaceae, β-glucuronidase-positive E. coli) and significant pathogens (Campylobacter spp., L. monocytogenes and Salmonella spp.), given their relevance for food safety. It should be noted that published studies vary greatly in sampling methodology and reporting units. Many investigations express results as CFU/cm2 using swabs or contact plates, whereas the present study applied ISO 18593-based cloth sampling and reports results as CFU/cloth. These methodological differences influence microbial recovery efficiency and therefore limit direct numerical comparison. For this reason, comparisons with the literature are interpreted cautiously and focus on qualitative trends rather than absolute values.

It is important to note that all samples were collected by the participants themselves using the sampling kits provided. While this approach was necessary for the logistics of the longitudinal study conducted in domestic environments, it may introduce variability due to differences in how individuals performed the sampling. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with this limitation in mind.

Comparable findings have been reported across Europe. In Ireland, Kennedy et al. (2005) [40] found high microbial loads in domestic refrigerators, with mean TVC of approximately 7.1 log CFU/cm2 and total coliforms around 4.0 log CFU/cm2; E. coli was detected on 6–7% of surfaces, indicating substantial hygiene deficiencies in a subset of households. In Italy, Catellani et al. (2014) [41] reported that more than 50% of the refrigerators examined showed TVC above 2 log CFU/cm2 and Enterobacteriaceae counts ranging from below the detection limit up to 4.18 log CFU/cm2, with contamination more frequent on lower shelves. More recently, Andritsos et al. (2021) [42] found that TVC exceeded 1.3 log CFU/cm2 in 41.4% of Greek households. In the present study, overall microbial loads on refrigerator surfaces were within the lower range of those reported in previous European surveys, yet a similar pattern of heterogeneity among households was observed, suggesting that surface contamination is primarily influenced by domestic hygiene habits and cleaning frequency rather than by differences in appliance performance or temperature, as reported in this study.

No target pathogens were detected in this study, as all refrigerator shelves and egg holder samples tested negative for Campylobacter sp., L. monocytogenes, and Salmonella spp. This absence of detection is in line with recent European findings reporting low but occasional pathogen occurrence in domestic refrigerators. Listeria monocytogenes was identified in 1 of 53 domestic refrigerators from households with vulnerable consumers in Portugal [38], while Salmonella spp. was found in 13.9% of egg racks from Serbian households [20]. Regarding Campylobacter, although it is rarely isolated from refrigerator environments [43], Campylobacter remains viable under refrigeration [44,45] and is strongly associated with poultry products, requiring control throughout storage and preparation [46]. These findings suggest that, although pathogen prevalence in domestic refrigerators is generally low, egg-contact areas may act as occasional contamination sources. The absence of pathogens in the present study likely reflects effective food hygiene practices, adequate refrigeration temperatures, and limited cross-contamination, reinforcing the importance of proper cleaning routines and segregation of raw and ready-to-eat foods within domestic refrigerators.

The absence of Campylobacter and Salmonella detection in eggs is consistent with European evidence indicating a low prevalence of these pathogens, typical confined to external shell contamination rather than internal contents, although eggs in Europe are sold unwashed and the “best before” label refers to shelf life stored at room temperature [47]. In Germany, Messelhäusser et al. (2011) [48] detected Campylobacter and Salmonella on 4.1% and 1.1% of shells, with all yolks tested negative. Correspondingly, UK retail surveys of imported eggs [31] identified an overall weighted Salmonella prevalence of 3.3%, exhibiting substantial geographic heterogeneity (e.g., 4.4% for Spanish vs. 0.3% for French eggs). Complementary catering surveys detected Salmonella in approximately 0.3–0.38% of pooled samples [32]. Systematic reviews similarly estimate mean Salmonella positivity in European table eggs at approximately 0.37%, indicating that contamination events at the retail level are infrequent [33].

In aggregate, these data support the plausibility of the observed absence of Salmonella at the consumer level and underscore that, despite the overall effectiveness of EU control measures, localized persistence of infection or deviations from prescribed biosecurity standards can occasionally result in outbreak-associated contamination within the production continuum.

According to The European Union One Health 2023 Zoonoses Report [32], eggs and egg products represented one of the predominant food vehicles in strong-evidence outbreaks: Among 95 outbreaks attributed to this vehicle, Salmonella accounted for 83 (87.4%), with a pronounced concentration in Poland and Spain. At the production stage, the EU-wide flock-level prevalence of Salmonella in laying hens was reported at 3.7%. This prevalence level reflects ongoing compliance with Regulation (EC) No 2160/2003 [49] on the control of Salmonella and other specified zoonotic agents, which mandates coordinated national control programs across Member States to achieve progressive reduction targets for Salmonella serovars of public health significance. These programs encompass vaccination of laying flocks, stringent biosecurity, feed control, and microbiological monitoring. The consistently low prevalence observed across the EU suggests substantial effectiveness of these harmonized interventions in minimizing Salmonella circulation at the primary production level.

5. Conclusions

In this two-year paired study, a considerable proportion of domestic refrigerators operated above the recommended threshold of 6 °C, and surface hygiene indicators—particularly TVC and Enterobacteriaceae—showed significant increases between 2024 and 2025. In contrast, E. coli occurrences were sporadic, and no consistent association was observed between mean temperature and microbial indicators, suggesting that behaviour-driven hygiene practices (e.g., cleaning frequency, segregation of raw and ready-to-eat foods, spill management, and door-opening behaviour) exert greater influence on microbial burden than temperature alone.

No target pathogens—L. monocytogenes, Salmonella spp., or Campylobacter spp.—were recovered from refrigerator surfaces across either sampling campaign. Likewise, in the egg component, all samples tested negative for Salmonella spp. and Campylobacter spp. on shells, in contents, and within egg-storage areas. These results are congruent with the low baseline prevalence reported in European surveillance data, reflecting the sustained effectiveness of upstream control measures under Regulation (EC) No 2160/2003 and associated EU zoonoses reduction programs.

Overall, the findings underscore the complementary roles of structural control (e.g., maintaining refrigeration at ≤5 °C with continuous temperature logging) and behavioural interventions (regular cleaning, removal of soiled packaging, strict segregation of raw and ready-to-eat items, and limiting door openings) in mitigating domestic microbial food safety risks. Strengthening consumer adherence to these simple, high-impact practices remains essential to sustaining the food safety gains achieved through EU-wide production-level Salmonella control policies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.R.B. and G.A.; methodology, A.R.B., B.F., P.O., H.G. and G.A.; formal analysis, A.R.B. and G.A.; investigation, A.R.B., B.F., P.O., H.G., M.J.S. and G.A.; data curation, A.R.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.R.B. and G.A.; writing—review and editing, A.R.B., B.F., P.O., H.G., M.J.S. and G.A.; supervision, M.J.S. and G.A.; project administration, G.A.; funding acquisition, G.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by FCT (Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology), PhD grant number (2023.04257.BDANA) attributed to Ana Rita Barata and the ongoing project GenoPheno4trait Ref. PTDC/BAA-AGR/4194/2021. The authors acknowledge the support given by FCT–Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, under the projects UID/04033/2025: Centre for the Research and Technology of Agro-Environmental and Biological Sciences and LA/P/0126/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/LA/P/0126/2020) and CECA-ICETA UIDB/00211/2020.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was not required for this study due to its non-interventional and minimal-risk design. The research was based on an anonymous, voluntary questionnaire assessing household food storage and hygiene practices. Sociodemographic variables (age and educational level) were collected only in broad categories, without recording any direct or indirect personal identifiers. No sensitive personal data were collected, and all responses were handled anonymously, in accordance with Portuguese and EU data-protection legislation. Participation was entirely voluntary, and informed consent was implied through completion of the questionnaire.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BPW | Buffer Peptone Water |

| ISO | International Organization for Standardization |

| PCA | Plate Count Agar |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| TBX | Tryptone Bile X-glucuronide |

| TVC | Total Viable Count |

| VRBG | Violet Red Bile Glucose |

References

- Insfran-Rivarola, A.; Tlapa, D.; Limon-Romero, J.; Baez-Lopez, Y.; Miranda-Ackerman, M.; Arredondo-Soto, K.; Ontiveros, S. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effects of Food Safety and Hygiene Training on Food Handlers. Foods 2020, 9, 1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Tang, Y. Enhancing Food Security and Environmental Sustainability: A Critical Review of Food Loss and Waste Management. Resour. Environ. Sustain. 2021, 4, 100023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagendijk, E.; Asséré, A.; Derens, E.; Carpentier, B. Domestic Refrigeration Practices with Emphasis on Hygiene: Analysis of a Survey and Consumer Recommendations. J. Food Prot. 2008, 71, 1898–1904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coorey, R.; Ng, D.S.; Jayamanne, V.S.; Buys, E.M.; Munyard, S.; Mousley, C.J.; Njage, P.M.; Dykes, G.A. The Impact of Cooling Rate on the Safety of Food Products as Affected by Food Containers. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2018, 17, 827–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farber, J.M.; Peterkin, P.I. Listeria monocytogenes, a Food-Borne Pathogen. Microbiol. Rev. 1991, 55, 476–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO); World Health Organization (WHO). Codex Alimentarius Guidelines on the Application of the General Principles of Food Hygiene to the Control of Listeria monocytogenes in Foods; CAC/GL 61-2007; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO); World Health Organization (WHO). Codex Alimentarius Commission Procedural Manual, 30th ed.; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2025; ISBN 978-92-5-139597-4. [Google Scholar]

- Osek, J.; Lachtara, B.; Wieczorek, K. Listeria monocytogenes—How This Pathogen Survives in Food-Production Environments? Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 866462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebesin, I.; Amoka, S.; Olomoko, C.; Olubunmi, O.; Balogun, A. Listeria monocytogenes in Food Production and Food Safety: A Review. J. Food Sci. Nutr. Ther. 2024, 10, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billah, M.M.; Rahman, M.S. Salmonella in the Environment: A Review on Ecology, Antimicrobial Resistance, Seafood Contaminations, and Human Health Implications. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2024, 13, 100407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zizza, A.; Fallucca, A.; Guido, M.; Restivo, V.; Roveta, M.; Trucchi, C. Foodborne Infections and Salmonella: Current Primary Prevention Tools and Future Perspectives. Vaccines 2024, 13, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampers, I.; Habib, I.; De Zutter, L.; Dumoulin, A.; Uyttendaele, M. Survival of Campylobacter spp. in Poultry Meat Preparations Subjected to Freezing, Refrigeration, Minor Salt Concentration, and Heat Treatment. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 137, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veronese, P.; Dodi, I. Campylobacter jejuni/coli Infection: Is It Still a Concern? Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maziero, M.T.; Cristina, T.; De Oliveira, R.M. Effect of Refrigeration and Frozen Storage on the Campylobacter jejuni Recovery from Naturally Contaminated Broiler Carcasses. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2010, 41, 501–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvoy, J.M.; Sheridan, J.J.; Blair, I.S.; McDowell, D.A. Microbial Contamination on Beef in Relation to Hygiene Assessment Based on Criteria Used in EU Decision 2001/471/EC. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2004, 92, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holcomb, D.A.; Stewart, J.R. Microbial Indicators of Fecal Pollution: Recent Progress and Challenges in Assessing Water Quality. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2020, 7, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bermudez-Aguirre, D.; Carter, J.; Niemira, B.A. An Investigation About the Historic Global Foodborne Outbreaks of Salmonella spp. in Eggs: From Hatcheries to Tables. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, O.; Kobalka, P.; Zhang, Q. Detection and Survival of Campylobacter in Chicken Eggs. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2003, 95, 1070–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parry, S.M.; Slader, J.; Humphrey, T.; Holmes, B.; Guildea, Z.; Palmer, S.R. A Case-Control Study of Domestic Kitchen Microbiology and Sporadic Salmonella Infection. Epidemiol. Infect. 2005, 133, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janjic, J.; Ivanovic, J.; Glamoclija, N.; Boskovic, M.; Baltic, T.; Glisic, M.; Baltic, M.Z. The Presence of Salmonella Spp. in Belgrade Domestic Refrigerators. Procedia Food Sci. 2015, 5, 125–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 18593:2018; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Methods for Surface Sampling. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- ISO 4833-1:2013; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Microorganisms—Part 1: Colony Count at 30 °C by the Pour Plate Technique. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- ISO 21528-2; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Detection and Enumeration of Enterobacteriaceae —Part 2: Colony-Count Technique. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- ISO 16649-1; Microbiology of the Food Chain-Horizontal Method for the Enumeration of Beta-Glucuronidase-Positive Escherichia coli—Part 1: Colony-Count Technique at 44 °C Using Membranes and 5-Bromo-4-Chloro-3-Indolyl Beta-D-Glucuronide. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Barata, A.R.; Nunes, B.; Oliveira, R.; Guedes, H.; Almeida, C.; Saavedra, M.J.; da Silva, G.J.; Almeida, G. Occurrence and Seasonality of Campylobacter spp. in Portuguese Dairy. Farms. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 383, 109961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 10272-1; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for Detection and Enumeration of Campylobacter spp.—Part 1: Detection Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- ISO 11290-1; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Detection and Enumeration of Listeria monocytogenes and of Listeria spp.—Part 1: Detection Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- ISO 6579-1; Microbiology of the Food Chain—Horizontal Method for the Detection, Enumeration and Serotyping of Salmonella —Part 1: Detection of Salmonella spp. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Düven, G.; Tiryaki Gündüz, G.; Kışla, D. Determination of Hygienic Status of Refrigerators Surface. Food Health 2021, 7, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, E.J.; Choi, K.O.; Sim, S.; Choi, J.; Uhm, Y.; Kim, S.; Lim, E.; Lee, Y.J. Patterns of Household and Personal Care Product Use by the Korean Population: Implications for Aggregate Human Exposure and Health Risk. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2020, 32, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulpiisova, A.; Dikhanbayeva, F.; Tegza, A.; Tegza, I.; Abzhanova, S.; Moldakhmetova, Z.; Uazhanova, R.; Alikhanov, K.; Yerzhigitov, Y.; Shambulova, G.; et al. Assessment of Food Safety Awareness and Hygiene Practices among Food Handlers in Almaty, Kazakhstan. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EFSA. The European Union One Health 2023 Zoonoses Report. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e9106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masson, M.; Delarue, J.; Blumenthal, D. An Observational Study of Refrigerator Food Storage by Consumers in Controlled Conditions. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 56, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ovca, A.; Škufca, T.; Jevšnik, M. Temperatures and Storage Conditions in Domestic Refrigerators—Slovenian Scenario. Food Control 2021, 123, 107715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azevedo, I.; Regalo, M.; Mena, C.; Almeida, G.; Carneiro, L.; Teixeira, P.; Hogg, T.; Gibbs, P.A. Incidence of Listeria spp. in Domestic Refrigerators in Portugal. Food Control 2005, 16, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvão, D.; Gaspar, P.D.; Da Silva, P.D.; Pires, L. Thermal Performance, Usage Behaviour and Food Waste of Domestic Refrigerators in a University Student Community: Findings towards Cities Sustainability. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2017, 223, 539–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrașcu, L.; Nicolau, A.I.; Neagu, C.; Didier, P.; Maître, I.; Nguyen-The, C.; Skuland, S.E.; Møretrø, T.; Langsrud, S.; Truninger, M.; et al. Time-Temperature Profiles and Listeria monocytogenes Presence in Refrigerators from Households with Vulnerable Consumers. Food Control 2020, 111, 107078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, L.; Bergis, H.; Gnanou-Besse, N.; Asséré, A.; Danan, C. Which Domestic Refrigerator Temperatures in Europe?-Focus on Shelf-Life Studies Regarding Listeria monocytogenes (Lm) in Ready-to-Eat (RTE) Foods. Food Microbiol. 2024, 123, 104595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergis, H.; Bonanno, L.; Asséré, A.; Lombard, B.; Polet, M.; Andersen, J.K. EURL Lm Technical Guidance Document on Challenge Tests and Durability Studies for Assessing Shelf-Life of Ready-to-Eat Foods Related to Listeria monocytogenes in Collaboration with a Working Group of Representatives of National Reference Laboratories (NRLs) for Listeria monocytogenes and a Competent Authority (CA). Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-07/biosafety_fh_mc_tech-guide-doc_listeria-in-rte-foods_en_0.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Kennedy, J.; Jackson, V.; Blair, I.S.; Mcdowell, D.A.; Cowan, C.; Bolton, D.J. Food Safety Knowledge of Consumers and the Microbiological and Temperature Status of Their Refrigerators. J. Food Prot. 2005, 68, 1421–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catellani, P.; Miotti Scapin, R.; Alberghini, L.; Radu, I.L.; Giaccone, V. Levels of Microbial Contamination of Domestic Refrigerators in Italy. Food Control 2014, 42, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andritsos, N.D.; Stasinou, V.; Tserolas, D.; Giaouris, E. Temperature Distribution and Hygienic Status of Domestic Refrigerators in Lemnos Island, Greece. Food Control 2021, 127, 108121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, V.; Blair, I.S.; McDowell, D.A.; Kennedy, J.; Bolton, D.J. The Incidence of Significant Foodborne Pathogens in Domestic Refrigerators. Food Control 2007, 18, 346–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haddad, N.; Burns, C.M.; Bolla, J.M.; Prévost, H.; Fédérighi, M.; Drider, D.; Cappelier, J.M. Long-Term Survival of Campylobacter jejuni at Low Temperatures Is Dependent on Polynucleotide Phosphorylase Activity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 7310–7318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Shibiny, A.; Connerton, P.; Connerton, I. Survival at Refrigeration and Freezing Temperatures of Campylobacter Coli and Campylobacter jejuni on Chicken Skin Applied as Axenic and Mixed Inoculums. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2009, 131, 197–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-S.; Kim, T.-Y.; Lim, M.-C.; Khan, M.S.I. Campylobacter Control Strategies at Postharvest Level. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2024, 33, 2919–2936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EC) No 589/2008 of 23 June 2008 Laying Down Detailed Rules for Implementing Council Regulation (EC) No 1234/2007 as Regards Marketing Standards for Eggs. Off. J. Eur. Union 2008, 163, 6–23. [Google Scholar]

- Messelhäusser, U.; Thärigen, D.; Elmer-Englhard, D.; Bauer, H.; Schreiner, H.; Höller, C. Occurrence of Thermotolerant Campylobacter spp. on Eggshells: A Missing Link. for Food-Borne Infections? Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 3896–3897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Commission Regulation (EC) No 2160/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 November 2003 on the control of Salmonella and other specified food-borne zoonotic agents. Off. J. Eur. Union 2003, 325, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.