Abstract

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are the largest family of diverse receptors in eukaryotic organisms, playing a critical role in modulating human physiology. It therefore comes as no surprise that about 36% of all currently available drugs target this superfamily. When an agonist binds to a GPCR, it induces conformational changes in the receptor that allow it to interact with intracellular proteins. This interaction triggers downstream signaling cascades that alter the cell’s activity. GPCR signaling is complex, as GPCRs transmit signals through coupling with G proteins, arrestins, and numerous other intracellular effectors. Different ligands, receptor subtypes, and cellular environments can result in the activation of distinct signaling pathways. Biased signaling through GPCRs has emerged as a frontier area in pharmacological research efforts towards designing targeted therapeutic interventions and enhancing drug efficacy and safety. This review presents the types of bias associated with GPCRs and the mechanisms underlying biased signaling. Examples of biased ligands and their therapeutic implications will be discussed. In addition, the inherent challenges in measuring signaling bias, and especially the translational gap between in vitro and in vivo assays and clinical outcomes, will be outlined.

1. Introduction to G Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs)

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) constitute a large superfamily of transmembrane receptors, encoded by approximately 800 genes in the human genome and accounting for a significant proportion of all protein-coding genes [1,2,3]. GPCRs share a conserved structure containing an extracellular N-terminal domain, seven transmembrane α-helices, and an intracellular C-terminal domain, connected by three extracellular and three intracellular loops. Only the sequence of the seven-transmembrane core of GPCRs is conserved; the lengths of the N-terminus, C-terminus, and third intracellular loop vary widely [4,5,6].

Based on sequence homology and functional similarity, GPCRs are categorized into six classes, namely class A (rhodopsin-like), class B (secretin receptor family), class C (metabotropic glutamate), class D (fungal mating pheromone receptors), class E (cAMP receptors), and class F (frizzled/smoothened). Classes A, B, C, and F are present in humans, whereas classes D and E are only in non-vertebrates. Based on phylogenetic analysis, the five families of GPCRs, known as the GRAFS system, include glutamate, rhodopsin, adhesion, frizzled, and secretin families [1,6,7].

GPCRs are predominantly expressed on the plasma membrane, but they are also located in intracellular membranes (see Section 3.4). They are highly expressed (more than 90%) in the central nervous system (CNS) [8], and crucially regulate a plethora of physiological functions, including cell growth, differentiation, and death, sensory perception like vision, taste, and smell, secretion processes, immune responses, cardiovascular regulation like contraction and vasodilation, and neural functions like neurotransmission, learning, memory, and pain [9,10,11]. They interact with a diverse array of ligands, including ions, photons (light), amino acids, peptides, sugars/carbohydrates, nucleotides, lipids, odorants, metabolic intermediates, hormones, and neurotransmitters [10,12,13]. GPCRs can also be constitutively active and signal in the absence of their endogenous ligand [12,14]. Certain GPCRs contain a single exon and do not undergo splicing, while others have multiple splice variants, resulting in more than one isoform [15]. Numerous pathophysiological conditions, such as allergic reactions, asthma, cardiovascular disorders, including hypertension and heart failure, migraine, pain, and psychotic conditions, necessitate the use of GPCR agonists or antagonists as therapeutics [16], and a major proportion of the currently marketed drugs target GPCRs [17,18,19].

2. GPCR Signaling

GPCR signaling has been predominantly studied for plasma membrane-residing GPCRs, in which receptor–ligand binding transduces signals from outside a cell to the inside. Classical textbook knowledge on GPCR signaling reports that the first step is the activation of the trimeric G proteins, which are composed of a membrane-anchored GDP-bound Gα subunit and a Gβγ dimer. GPCR activation induces conformational changes that cause the receptor to interact with the G protein and act as a guanine nucleotide exchange factor for the Gα subunit [10,18,20]. GTP-bound Gα dissociates from the Gβγ dimer and from the GPCR, allowing both Gα and Gβγ to interact with downstream effectors, following distinct and independent signaling pathways. Through the intrinsic GTPase activity of the Gα subunit, GTP is hydrolyzed to GDP, the signal terminates, and the G protein heterotrimer reassembles [21,22,23,24].

The human genome encodes 16 (21 if splice variants and pseudogenes are included) Gα, 5 Gβ, and 12 Gγ functional isoforms [20,21]. Based on their Gα subunit, G proteins are categorized into four families: Gαs, Gαi/o, Gαq/11, and Gα12/13. Gαs stimulates adenylyl cyclase (AC) to increase cAMP levels, while Gαi/o inhibits AC and decreases cAMP levels. Gαq/11 activates phospholipase β, leading to the generation of diacylglycerol and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3), which releases Ca2+ from intracellular stores. Gα12/13 activates Rho guanine nucleotide exchange factor, leading to enhanced Rho GTPase activity. Gβγ subunits regulate ion channels [18,21,23,25,26,27].

Following ligand binding, GPCRs undergo desensitization and internalization, processes originally thought to only attenuate signaling [21]. It is now known that following internalization, GPCRs signal in a β-arrestin-dependent or independent and G protein-dependent or independent manner [28,29,30]. The mammalian family of arrestins comprises four known isoforms. Arrestins-1 and -4, the visual arrestins, are expressed in the retina and interact with photopigments (rhodopsin and cone opsins). Arrestins-2 and -3, known as β-arrestins 1 and 2, are ubiquitously expressed in various tissues and interact with all GPCRs [29,31,32]. Despite the sequence and structural similarity of β-arrestins, their different preferences for distinct GPCRs result in differences in signaling and functional outcomes [33]. GPCR phosphorylation is required for the creation of high-affinity binding sites for β-arrestins. It is achieved either by protein kinases A and C or by GPCR kinases (GRKs) [18], which phosphorylate Ser and Thr residues in the third intracellular loop and the C-terminal tail of the receptor [34]. The importance of the phosphorylation step is further supported by findings that different phosphorylation patterns result in distinct receptor conformations and dictate different downstream signaling pathways [32,33,35,36,37,38]. Of the seven known GRKs, GRKs 1 and 7 are expressed in the retina and act as rhodopsin and cone opsins kinases, respectively; GRKs 2, 3, 5, and 6 are ubiquitously expressed. The expression of GRK4 is limited to a few tissues [39]. GRK4 subfamily members (GRK4/5/6) have been reported to be constitutively active and to phosphorylate unstimulated GPCRs [39,40].

When β-arrestins bind to a phosphorylated GPCR, coupling of G proteins to the receptor ends, and the GPCR-β-arrestin complex is channeled into clathrin-coated vesicles through β-arrestin’s interactions with the heavy chain of clathrin, clathrin adaptive protein 2 (AP2), and other endocytic proteins [22,41]. The membrane invaginates and, with the involvement of the GTPase dynamin, the clathrin-coated vesicles bud off into the cytosol [22]. Ubiquitinylation of β-arrestins is essential for endocytosis, enhances clathrin-AP2 binding, stabilizes the complex, and facilitates endocytosis [21,22]. Other endocytic mechanisms (clathrin- or arrestin-independent) for GPCR internalization have also been reported [42], adding to the complexity of GPCR signaling. Finally, it is well appreciated that β-arrestins can initiate alternative signaling pathways by acting as scaffold proteins, recruiting and activating downstream effectors such as extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK1/2), Src family kinases, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase independently of their binding to GPCRs [2,43,44,45].

3. GPCR Bias and Types of Biased Signaling

The GPCR bias story began to unravel in 1987, when a review on the serotonergic system first speculated on the potential benefits of selective drugs that would specifically activate downstream signaling pathways [46]. Terry Kenakin also discussed the topic in 1995, highlighting data on agonists that differentially activated GPCRs, such as muscarinic and adrenergic receptors [47]. Several subsequent studies have demonstrated that different ligands acting on the same GPCR produce different responses, due, for example, to the activation of a certain G protein over another [27,44]. These observations led to the concept that active receptors exist in more than one conformation, introducing the terms of functional selectivity or biased signaling [48]. During the 1990s and early 2000s, the idea that a ligand might preferentially activate one pathway over another, i.e., the G protein pathway over the β-arrestin pathway or vice versa, was widely accepted. Research then focused on identifying ligands that showcased this signaling bias [29,49]. Over the last two decades, methodological advances, such as the development of biosensors and the acquisition of high-resolution structures, have shed more light on the mechanistic aspects of biased signaling [50,51,52,53]. Terms such as temporal and spatial bias (see Section 3.4) enriched the notion that GPCR signaling is dynamic and complex [10,18,54,55,56]. A plethora of biased ligands have been discovered, some of which have been channeled into the preclinical or clinical pipeline (e.g., oliceridine) [48,57]. Emphasis has since been placed on identifying biased agonists with appropriate efficacy to produce a therapeutic response, minimizing the risk of side effects. Biased signaling can occur at various levels downstream of a ligand binding to its GPCR and can be categorized as follows (Figure 1):

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the different types of biased signaling downstream of GPCRs. The text describes each type in more detail. x, y, z, and n represent the different possible isoforms involved in the formation of the Gβγ complexes.

- (1)

- Gα subunit bias: A GPCR can link to more than one of the 16 Gα subunits, each of which has its own effectors and signaling molecules. One can therefore envision numerous possibilities for each receptor. An example is the protease-activated receptor 1 (PAR1). Thrombin activation of PAR1 signals through Gαq, Gα12/13, and β-arrestin 2, while the coagulation protease–activated protein C (aPC) signals through Gα12/13 and β-arrestin 2, but not Gαq [58].

- (2)

- Gβγ subunit bias: The 5 Gβ and 12 Gγ subunits form 60 possible dimer combinations that differ in their subcellular translocation and downstream signaling kinetics and efficacy [59]. A recent study supports the notion that all β-arrestin effects mediated by GRK2/3 are Gβγ-dependent, while the β-arrestin effects mediated by GRK5/6 are independent of G proteins [60]. Certain Gβγ combinations specifically affect ion channel function, and tissue-specific expression of Gβ and Gγ subunits suggests that particular subunit combinations may correspond to distinct functions in specific tissues and organs [61].

- (3)

- G protein over β-arrestin bias: G protein bias over β-arrestin has been observed with numerous endogenous or exogenous ligands, as exemplified in the following sections.

- (4)

- β-arrestin over G protein bias: The conformational patterns of the complex between the ligand, the receptor, and the β-arrestin dictate the effectors to which arrestin will bind and how it will regulate G protein signaling [62]. Examples are discussed in the following sections.

- (5)

- β-arrestin bias: By selectively silencing each β-arrestin, it has been demonstrated that β-arrestins 1 and 2 have differential affinity for different GPCRs and activate different downstream mediators [41,63]. One example is the angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1 R), which interacts with both β-arrestins 1 and 2. Each β-arrestin stabilizes different AT1 R conformations with distinct agonist-binding affinities, suggesting that it may be possible to design AT1R-biased agonists that selectively recruit β-arrestin 1 or 2 [64]. However, the functional consequence of such an approach remains unclear.

- (6)

- GRK bias: It is known that several phosphate groups must be attached to the receptor to promote β-arrestin recruitment. Variability in receptor–ligand conformations leads to the selective recruitment of specific GRKs, resulting in distinct phosphorylation patterns, known as phosphorylation “barcodes”, and unique downstream signaling pathways [35,36,65]. Recent studies on the AT1R have shown that upon binding of angiotensin II, the recruitment of β-arrestin depends on both GRK2/3 and GRK5/6; upon binding of the β-arrestin-biased ligand TRV027, recruitment of β-arrestin depends solely on GRK5/6 [66]. GRK-specific phosphorylation “barcodes” can differentially recruit β-arrestin 1 and β-arrestin 2, activating distinct β-arrestin-mediated signaling pathways [67]. Other than acting as intermediates between G proteins and β-arrestins, GRKs may also mediate GPCR-independent signaling. This notion is supported by a recent study describing the development of GRK2-biased β2 adrenergic receptor partial agonists that increase glucose tolerance in preclinical models of diabetes and obesity, without significant cardiovascular effects [68].

3.1. Natural (Intrinsic or Physiological) Bias

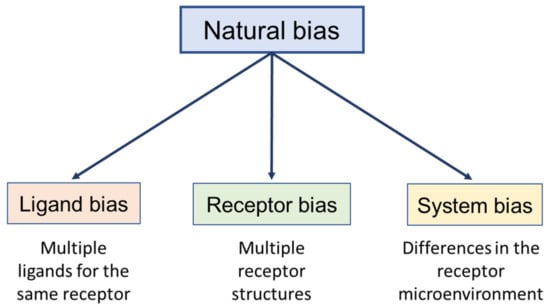

Bias exists inside the human body and is known as natural (or physiological) bias. Natural bias can be divided into endogenous ligand bias, receptor bias, and biological system bias (Figure 2). Receptor and system biases are discussed in Section 3.3 and Section 3.4, respectively. Natural ligand bias is observed for receptors with multiple ligands, contributing to fine-tuned signaling that ultimately regulates physiological cell responses and the homeostasis of one’s own organism [69]. Prevalent examples of natural ligand bias are mentioned below.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the different forms of natural bias. The same types apply to synthetic ligands.

Opioid receptors (μ, δ, κ) are activated by more than 20 different endogenous opioid peptides categorized as dynorphins, endorphins, or enkephalins, which favor different signaling pathways, leading to biased signaling at only one or all three opioid receptors [70,71,72]. Understanding how endogenous opioid peptides act as biased agonists to control physiological processes has enabled the design and synthesis of biased opioids with favorable pharmacological properties, discussed in Section 3.2.

The chemokine receptor family consists of approximately 20 receptors that bind to at least 50 endogenous ligands [73]. CCL19 and CCL21 are endogenous ligands of CCR7, a member of the CC chemokine receptor family. They both activate G protein signaling, but only CCL19 induces β-arrestin recruitment and receptor internalization [57]. Similarly, among the endogenous ligands of CXCR3, a member of the CXC chemokine receptor family, only CXCL11 is β-arrestin-biased [57].

AT1R signaling towards β-arrestins contributes to various physiological and pathological outcomes in the cardiovascular system, including cellular proliferation, hypertrophy, and fibrosis, linked to hypertension, atherosclerosis, and heart failure [21,74,75]. The octapeptide angiotensin II is an AT1R-balanced ligand that leads to vasoconstriction and cardiac or renal remodeling. An endogenously produced angiotensin heptapeptide, which lacks the angiotensin II C-terminal Phe residue, acts as a biased ligand that antagonizes the angiotensin II/AT1R/Gαq pathway, but promotes the recruitment of β-arrestin to the AT1R, explaining, at least partly, its vasodilatory and cardioprotective effects [76].

Galanin receptor 2 (GalR2) is a GPCR with two endogenous, yet structurally different, peptide ligands, galanin and spexin. In animal models, the ligands have different effects on appetite behavior; galanin increases food intake, while spexin does not. Spexin shows bias towards the Gαq pathway over β-arrestin signaling, while galanin signals through both Gαq and β-arrestin pathways. They also exhibit different rates for GalR2 internalization [77].

The calcium-sensing (CaS) receptor, which plays multiple roles in regulating calcium concentration in the body, binds diverse endogenous ligands, including Ca2+, Mg2+, amino acids, polyamines (such as spermine), and glutathione. Among them, Ca2+ and spermine show bias and activate different signaling pathways. Ca2+ preferentially induces inhibition of cAMP effects (Gαi/o signaling) and IP3 stimulation (Gαq/11) over ERK1/2 phosphorylation, whereas spermine favors ERK1/2 activation via β-arrestins [78].

Immune cells express the GPCRs hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 3 (HCA3) and GPR84, which are activated by medium-chain fatty acids and regulate metabolism. Both receptors show overlapping expression, share at least one agonist (3-hydroxydecanoic acid), and are coupled to Gαi/o proteins. The binding of 3-hydroxyoctanoic acid to HCA3 leads to activation of Gαi/ο and recruitment of β-arrestin 2, resulting in anti-inflammatory effects. The same ligand binding to GPR84 activates ERK1/2 through Ga15 and does not recruit β-arrestin 2, resulting in pro-inflammatory signaling [79,80].

When activated, the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR) in somatic cells of the gonads activates several G proteins (Gαs and Gαi/o) and β-arrestin. FSH naturally occurs in differentially glycosylated forms that exhibit biased signaling. The less glycosylated FSH21/18 preferentially activates the Gαs/cAMP/PKA pathway and is 10-fold more potent in inducing aromatase activity and increasing estrogen levels than the fully glycosylated FSH24. FSH21/18 is more abundant in younger females, and FSH24 in men and post-menopausal women [81].

Activation of PAR1 by its protease ligands is also biased. For example, thrombin triggers coupling to Gαq, Gα12/13, and β-arrestin 2, and aPC favors coupling to Gα12/13 and β-arrestin 2 but not Gαq [58]. The mechanism of bias in PARs is due to the different proteases (thrombin, elastase, matrix metalloproteinase 1, and aPC) that act as ligands, cleaving the receptor at distinct sites and unmasking different tethered ligands, which interact differentially with the cleaved receptor and activate biased signaling pathways [82].

3.2. Synthetic Ligand Bias

Ligand bias is an intrinsic property of the ligand and, besides endogenous ligands, as discussed in Section 3.1, extends to synthetic ligands, which are the result of research attempts to develop drugs with higher efficacy and better safety profiles [21,57,83,84,85,86].

One of the best-studied receptors for biased agonism is the μ-opioid receptor. It all started with evidence showing that the serious adverse effects of morphine on the respiratory and gastrointestinal systems are downstream of β-arrestin 2. This notion was verified with studies on β-arrestin 2 knockout mice, in which morphine had the same analgesic effect, but fewer side effects [87]. This has led to the development of biased agonists that activate the G protein, but not β-arrestin 2, resulting in potent analgesia with fewer severe side effects [88]. One such drug, oliceridine, was approved by the FDA in 2020 for short-term management of moderate-to-severe acute pain, with reduced risk of respiratory depression. In the first trial in healthy volunteers, oliceridine was overall well-tolerated [89]. In a phase I trial, oliceridine at lower doses caused more analgesia than morphine with less respiratory depression and nausea [90]. In a phase II trial, oliceridine caused analgesia faster and more effectively than morphine in patients with acute postoperative pain [91]. In two phase III trials (APOLLO-1 and -2), oliceridine provided post-operative analgesia with less severe gastrointestinal and respiratory depression compared to morphine [92,93]. Many more G protein-biased μ-opioid receptor agonists are being developed and studied [94]. However, recent work argues against the initial evidence on the involvement of biased signaling in the effect of such agonists by showing that in mice, which express mutant phosphorylation-deficient μ-opioid receptors that cannot recruit β-arrestin, morphine and fentanyl produce a substantially higher analgesic effect, but also profound side effects, such as respiratory depression and constipation [95]. Similar effects of fentanyl and morphine were observed in β-arrestin 2 knockout mice [96]. By using in vitro assays, in which they overexpressed receptors and signaling molecules, it was demonstrated that a low intrinsic efficacy may be the mechanism by which novel opioids may display a better safety profile [97]. Following administration of morphine and two novel μ-opioid receptor agonists (kurkinorin and kurkinol) in β-arrestin 2 knockout mice, the side effects of these opioid agonists occurred irrespective of β-arrestin 2 activation [98], further questioning the development of G protein-biased agonists as analgesics with a favorable safety profile. The difficulty in clearly concluding on this debate is emphasized by a subsequent work that reanalyzed the data of the study by Gillis et al. [97] and concluded that partial agonism alone cannot explain the favorable effects of oliceridine and the other studied opioids, and that G protein-biased signaling is also clearly involved [99].

Another receptor that is being studied as a target for analgesics is the δ-opioid receptor. Agonists of the δ opioid receptor have analgesic effects in models of chronic pain, but a limiting factor is that they may cause epileptic episodes. A δ-opioid receptor-selective, G protein-biased agonist, PN6047, alleviates chronic pain and, following prolonged treatment, does not cause tolerance, respiratory depression, or proconvulsant activity [100]. The Phase I clinical study has confirmed that PN6047 is safe and tolerable at doses predicted to be efficacious [101]. The drug is now entering a Phase IIa clinical study [102]. Similarly, to PN6047, TRV250 is a G protein-biased δ-opioid receptor-selective agonist developed for the treatment of acute migraine, which was found to be safe and tolerable in a Phase I clinical study [103]. The treatment of migraine with G protein-biased δ-opioid receptor-selective agonists is supported by additional data on biased agonists, such as KNT-127, which effective in treating migraine-associated pain and aura in preclinical models, without seizurogenic activity [104].

The cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) is highly expressed in the CNS and binds endogenous, plant-derived, and synthetic cannabinoids, such as Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol. When activated, it predominantly signals through the Gαi/o protein to provoke analgesia, while its coupling with β-arrestin results in tolerance [105]. Efforts to develop CB1 receptor agonists that are biased for G protein-dependent signaling, with little to no β-arrestin 2 recruitment, have led to experimental compounds, such as a novel class of indole quinulidinones that cause improved cannabinoid-induced analgesia and provoke significantly less severe adverse effects and reduced motor suppression compared to non-biased full agonists [106].

Dopamine receptors are targets for treating the motor and cognitive deficits of Parkinson’s disease. To date, most drugs are agonists for the D2 dopamine receptor subtype. However, it has been observed that the D1 receptor subtype is highly expressed in the striatum and prefrontal cortex, and is also involved in motor and cognitive disorders. Based on this observation, there are efforts to develop D1-selective agonists to mitigate Parkinson’s disease-related movement disorders and cognitive impairment. To date, catechol-based selective D1 receptor agonists have failed to meet clinical criteria, mostly due to rapid receptor desensitization and tachyphylaxis. Non-catechol agonists have been evaluated [107,108,109]. Among them, tavapadon, a partial D1 receptor agonist biased for G protein signaling, has shown promising safety and efficacy data in phase III clinical trials for Parkinson’s disease [110].

The 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A (5-HT2A) receptor in the CNS also regulates cognitive functions and may be involved in the etiology of schizophrenia. Pimavanserin, an inverse agonist of the 5-HT2A receptor, is an atypical antipsychotic approved to treat psychosis associated with Parkinson’s disease. It was recently demonstrated to decrease the basal activity of Gαi/o protein without affecting the activity of Gαq/1, classifying it as a biased inverse agonist. Ketanserin, on the other hand, is a biased 5-HT2A receptor partial agonist that activates the Gαq/11 protein, but does not affect the Gαi/o or β-arrestin pathways, and is used for the treatment of hypertension [111,112]. 5-HT2A is a receptor for psychedelics, such as psilocybin and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), but also for non-hallucinogenic compounds, such as lisuride and ergotamine, despite their significant structural similarities [113]. The finding that Gαq/11, rather than β-arrestin 2 activation downstream of the 5-HT2A receptor, is essential for inducing psychedelic-like effects [114,115,116] helped explain this discrepancy, as well as why ketanserin reverses the psychedelic activities of classical psychedelics [117]. By analyzing the crystal structures of the 5-HT2A receptor bound to serotonin, lisuride, psilocin, or LSD, a binding mode that preferentially recruits β-arrestin over G protein was uncovered and used to design analogs, such as HCH-7113, which retain their anti-depressive efficacy but are non-hallucinogenic [116]. A recent in vitro study, however, argues against the biased signaling of the 5-HT2A receptor, showing that non-psychedelic 5-HT2A receptor agonists have low intrinsic efficacy in both Gαq and β-arrestin 2 signaling pathways, which may explain why they are non-psychedelic [118], similarly to what has been suggested for the better safety profile of oliceridine [97].

As discussed in Section 3.1, β-arrestin-biased ligands of the AT1R may be efficacious in various cardiovascular pathologies, such as hypertension, atherosclerosis, and heart failure [119]. TRV027 is developed as an AT1R-biased agonist that selectively acts through β-arrestin and was shown to be as effective as losartan in lowering blood pressure in an experimental model of deoxycorticosterone acetate-salt hypertension [120]. It also causes neonatal-specific, long-acting positive inotropic effect with minimal impact on the heart’s workload and oxidative stress [121]. Despite promising data and the first clinical trial in healthy volunteers, in which TRV027 was found to be well-tolerated and safe [122], it failed in Phase II clinical trial to show any benefit over placebo in improving overall outcomes for patients with acute heart failure [123,124], suggesting that there is still a long way to go to developing therapeutically efficacious AT1R biased agonists.

Beta (β)-adrenergic receptors are another extensively studied example of GPCRs showing biased agonism. Most of the known β2-adrenergic receptor agonists demonstrate similar G-protein signaling activity but exhibit differential β-arrestin bias. Through G protein signaling, β2-adrenergic receptor agonists induce relaxation of airway smooth muscle cells, leading to bronchodilation, improved airflow, and reduced morbidity. Through β-arrestin signaling, they promote receptor desensitization and loss of effectiveness. There are efforts to develop β2-adrenergic receptor agonists that favor Gαs coupling over β-arrestin binding and thus will not desensitize the receptor. Such drugs may be effective in patients who display poor responsiveness or become tolerant to chronic therapy with a balanced β2-adrenergic receptor agonist [125,126]. Among the therapeutically used bronchodilators, salmeterol has a 5 to 20-fold bias towards Gαs over β-arrestin signaling [125,127]. However, it was recently shown that it also acts as a partial agonist of Gαs coupling and a full agonist for Gαi/ο recruitment [128], suggesting that biased signaling is far more complex than expected and requires meticulous research.

On the other hand, arrestin-biased β-adrenergic receptor agonists appear to have a cardioprotective effect. Such ligands include carvedilol and nebivolol. Carvedilol is a widely used β- and α1-adrenergic receptor inverse agonist at the G protein pathway, but a β-arrestin-biased agonist that stimulates ERK1/2 phosphorylation and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) transactivation, leading to cardioprotection [125,129,130]. The dual signaling of carvedilol is believed to be the reason it outperforms other β-adrenergic receptor blockers, leading to improved clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure. Nebivolol is a partially selective β1 adrenergic receptor antagonist at the G protein pathway and a β-arrestin-biased agonist, which also promotes ERK1/2 phosphorylation and EGFR transactivation, like carvedilol. However, it also acts as a β3-adrenergic receptor agonist, which causes vasorelaxation via endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation [125,131].

Arrestin-biased β1-adrenergic receptor agonists, such as carvedilol and alprenolol, also induce memory reconsolidation through ERK1/2 signaling, suggesting a potential role for such ligands in the treatment of memory-related disorders [132]. On the other hand, β1-adrenergic receptor agonists biased for Gαs coupling may also positively affect cognitive functions and memory reconsolidation, due to the protective effect of the Gαs activation in neuroinflammatory pathologies. Research has led to STD-101-D1, a selective β1 adrenergic receptor partial agonist biased for Gαs protein signaling, that needs to be further evaluated for the treatment of cognitive disorders [133].

To date, the use of β2-adrenergic receptor agonists for glycemic management has been hampered due to cardiac side effects related to Gαs and desensitization related to β-arrestin. GRK2 is essential for β2-adrenergic receptor-mediated glucose uptake, and compounds biased towards GRK2 coupling compared to balanced β2-adrenergic receptor agonists appear to outperform in preclinical models of hyperglycemia and obesity, with fewer cardiac and muscular side effects. They are to be tested in clinical trials for type 2 diabetes and obesity [68].

More recently, Shen et al. [134] developed a small molecule, AP-7-168, which biases β2-adrenergic receptor signaling through dimerization. AP-7-168 acts as a G protein-biased agonist, causing sustained bronchodilation with delayed receptor desensitization [135]. This bronchorelaxation effect is due to AP-7-168 functioning as a molecular glue, binding to the transmembrane helices 3, 4, and 5 of two monomers of the β2-adrenergic receptor to promote β2-adrenergic receptor dimerization and prevent β-arrestin recruitment [134]. These data are one example of ligand-induced dimerization as a strategy to exploit GPCR biased signaling.

Intracellular GPCR ligands may also activate biased signaling. For example, a small molecule, SBI-553, which binds to the intracellular interface of the neurotensin receptor 1 (NTSR1), has been shown to activate β-arrestins over Gαq and selectively attenuate addictive behaviors [136]. An analog of SBI-553, which contains a fluorine-to-methyl group substitution, SBI-810, has a potent peripheral and central antinociceptive effect in mice by specifically enhancing the β-arrestin 2 signaling downstream of the NTSR1, with an improved safety profile [137]. After minor chemical modifications, such analogs may also modify the G protein subtype that interacts with the receptor [138]. The use of intracellular modulators to modify G protein selectivity may apply to numerous GPCRs, which have an intracellular binding pocket accessible to small molecules, such as the muscarinic receptor M3 and the β2-adrenergic receptor [139].

The human melanocortin−4 receptor (MC4R) is expressed in the nervous system and regulates food intake and energy expenditure, but triggers cardiovascular side effects through the sympathetic nervous system. Ligands biased towards the Gαq pathway, such as the MC4-NN2-0453 peptide, suppress food intake with minimal cardiovascular effects due to Gαs, and were investigated as potentially better drugs for obesity [140,141]. However, in the first randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, MC4-NN2-0453 had no effect in reducing body weight in healthy obese patients, although it had an acceptable safety and pharmacokinetic profile [141].

Table 1 summarizes the various mechanisms by which synthetic ligands cause biased signaling. Table 2 summarizes examples of GPCR-biased drugs that have been approved or are currently in clinical trials. An extensive list of biased ligands can be found at https://biasedsignalingatlas.org/ and https://biasdb.drug-design.de/.

Table 1.

Mechanisms through which synthetic ligands bias the signaling pathway to be activated. The text contains more details, and the table is not exhaustive of the relevant literature. AR: adrenergic receptor.

Table 2.

Examples of GPCR-biased drugs approved or in clinical trials. Among the approved drugs, oliceridine, TRV250, and PN6047 were/are developed as biased agonists, while the others were shown to initiate biased signaling after their approval. AR: adrenergic receptor.

3.3. Receptor Bias

Receptor bias refers to the receptor’s tendency to preferentially activate one downstream signaling pathway over another, regardless of the ligand. Receptor bias is a form of natural bias, and the mechanisms known to lead to receptor bias are summarized in Table 3. One such mechanism is related to the structural properties of the receptor, usually resulting from mutations, genetic polymorphisms, or post-translational modifications [142]. The most striking example of receptor bias is that of the atypical chemokine receptors (ACKRs), which do not couple to G proteins, but signal through β-arrestins. An example is ACKR3 (CXCR7), which activates β-arrestin signaling pathways upon binding, interferon-inducible T-cell alpha chemoattractant and CXCL12 [143]. With the use of peptides derived from the N-terminal regions of chemokines and modified full-length chemokines, it was shown that the binding of chemokines to ACKR3 was different and less stringent compared to the binding to CXCR4, CXCR3, and other classical chemokine receptors [144], and ACKR3 is more prone to activation even by antagonists of the classical chemokine receptors [145]. It was recently demonstrated that ACKR1, formerly known as Duffy Antigen Receptor, promotes the dimerization of CXCL12, providing evidence for a novel mechanism of ACKRs’ contribution to the functional selectivity of chemokines’ signaling [146]. The monomer CXCL12 has a higher affinity for CXCR4, while ACKR1 and ACKR3 have higher affinity for the CXCL12 dimers [147,148].

Another example of receptor bias is observed in the FSHR, for which active and inactive mutations, including single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), have been reported. One such mutation is the A189V that impairs the G protein pathway without affecting the β-arrestin pathway and leads to subfertility in men and infertility in women. The p.N680S (c.2039A > G) SNP has been linked to receptor-dependent β-arrestin bias in women bearing the Ser variant [81].

Vasopressin receptor 2 (V2R) is a GPCR that promotes water reabsorption in the kidney collecting ducts to maintain body water homeostasis. Compared to the wild-type receptor, the human V2R mutation R137H associated with familial nephrogenic diabetes insipidus leads to β-arrestin-biased signaling and enhanced receptor internalization, even in the absence of its endogenous ligand (the antidiuretic hormone, arginine vasopressin). Interestingly, biased agonist pharmacochaperones can enter the cells and interact with the intracellular mutated V2Rs, enabling their translocation to the plasma membrane. They then activate the Gαs pathway without recruiting β-arrestins, providing a long-acting alternative to V2R antagonists for the treatment of familial nephrogenic diabetes insipidus [149,150].

CaS receptor represents another good example of receptor bias, with over 230 mutations identified to date. These mutations are known to be fundamental for diseases such as Bartter syndrome type V, familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia, and autosomal dominant hypercalcemia, and lead to stabilization of different receptor conformations that differentially activate G protein or β-arrestin downstream pathways [151,152,153].

The glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP1R) is primarily expressed in the pancreas and brain, and mediates the effects of GLP1, enhancing insulin secretion, regulating blood sugar, and slowing gastric emptying. GLP1R mutations, such as the T149M mutation, negatively affect the cell membrane expression of the receptor and deregulate glucose homeostasis. An allosteric GLP1R ligand biased towards β-arrestin 2 signaling has shown good efficacy in restoring glucose homeostasis and is being studied as a therapeutic option [154,155].

Melanocortin-3 receptor (MC3R) regulates energy balance, growth, puberty, and circadian rhythms. Mutated forms of the receptor have been shown to lead to biased signaling depending on the mutation, and some of these mutations might contribute to obesity pathogenesis [155]. Interestingly, following stimulation by the endogenous α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone, some mutants display biased activation of the Gαs-cAMP pathway, whereas other mutants show biased activation of the β-arrestin-ERK1/2 pathway [156]. Mutants of the MC4R with biased signaling towards β-arrestin or Gαq/11 activation have also been identified; however, further studies are required to get conclusive evidence on their functional significance [142,157].

There are more receptors, whose mutant isoforms display biased signaling, and a potential association between biased signaling and the relevant pathological condition has been hypothesized. For example, mutations of the prokineticin receptor 2 are associated with Kallmann syndrome; mutations of the G protein-coupled receptor 54 are linked to idiopathic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism; mutations of the thyrotropin receptor are linked to hypothyroidism and resistance to thyrotropin; mutations in melatonin receptors have been related to autism spectrum disorders, circadian disorders, and diabetes [142].

Another mechanism through which GPCRs might be responsible for biased signaling is through their heterodimerization. An example is the biased signaling elicited by adenosine, which depends on both the receptor heterodimerization and the concentration of the ligand. At low concentrations, adenosine preferentially binds to the A1 receptor, which signals through the Gαi protein. At higher concentrations, adenosine also binds to the A2A receptor, which heterodimerizes with A1 and decreases its affinity for agonists. In this case, adenosine signals through the Gαs protein, which is activated by the A2A receptor [158]. The formation of A1-A2A receptor heterodimers was demonstrated using a combination of radioligand-binding, co-immunoprecipitation, bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET), and time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) techniques [159]. Another example is the heterodimerization of the μ- and δ-opioid receptors, which leads to constitutive recruitment of β-arrestin 2 and, consequently, to morphine tolerance. A combination of morphine and a δ-opioid receptor antagonist dissociated β-arrestin 2 from the heterodimer and enhanced morphine’s effect, while delaying tolerance [160]. The μ- and δ-opioid heterodimer exhibits restricted distribution in the brain and is upregulated in response to chronic morphine administration. Compounds, such as CYM51010, which specifically target these heterodimers but not the corresponding monomeric receptors, have an antinociceptive effect similar to morphine, but decreased tolerance [161]. The receptor for platelet-activating factor (PAF) has also been shown to form dimers and oligomers, even at low densities, in transfected cell lines. These oligomeric structures are biased for G protein signaling, with decreased β-arrestin recruitment [162]. ACKR3 has been shown to affect CXCL12 signaling by forming heterodimers with CXCR4, limiting activation of G proteins by CXCR4 and the chemotaxis of lymphocytes induced by CXCL12 [163]. Similarly, macrophage migration inhibitory factor, an ACKR3 agonist, enhanced the formation of CXCR4-ACKR3 heterodimers and inhibited CXCL12-induced platelet activation and thrombus formation [164]. CXCR4-ACKR3 heterodimers exist in vivo and play a potentially significant role in promoting colorectal tumorigenesis by recruiting β-arrestin 1 to the nucleus and enhancing histone demethylation and transcription of inflammatory factors and oncogenes [165]. Despite the increasing number of examples that appear in the literature, oligomerization of class A GPCRs is disputed, possibly due to spatial constraints from the cell membrane, such as local lipid environment, viscosity, and elasticity, which affect the stability and lifetime of the monomer-dimer equilibrium. For example, using state-of-the-art approaches, Kubatova et al. (2025) [166] investigated the effect of different membrane mimetic environments on the dimerization propensity of β1 adrenergic receptors. They found that receptor dimerization depends on the membrane composition and physical constraints, highlighting the complexities in studying class A GPCR dimerization.

Table 3.

Main mechanisms related to receptor bias. The text contains more details, and the table is not exhaustive of the relevant literature.

Table 3.

Main mechanisms related to receptor bias. The text contains more details, and the table is not exhaustive of the relevant literature.

| Mechanism | Bias | Receptor(s) | Potential Implication | Ligand(s) | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receptor mutations/SNPs | β-arrestin over G protein | FSHR (A189V) | Sub/infertility (men/women) | Unknown | [81] |

| V2R (R137H) | Familial nephrogenic diabetes insipidus | Unknown | [149,150] | ||

| CaS (several) | Bartter syndrome type V, familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia, and autosomal dominant hypercalcemia | Unknown | [151,152,153] | ||

| GLP1R (T149M) | Disturbed glucose metabolism | Allosteric modulator | [154,155] | ||

| MC3R (several) | Obesity | Unknown | [156] | ||

| G protein over β-arrestin | CaS (several) | Bartter syndrome type V, familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia, and autosomal dominant hypercalcemia | Unknown | [151,152,153] | |

| MC3R (several) | Obesity | Unknown | [156] | ||

| Receptor di/oligomerization | Gs over Gi | A1/A2A receptor heterodimer | Inhibition of A1 signaling | High adenosine concentrations | [158] |

| β-arrestin over G protein | μ-opioid/δ-opioid receptor heterodimer | Morphine tolerance | Prolonged morphine treatment, CYM51010 | [160,161] | |

| G protein over β-arrestin | PAF receptor di/oligomers | Decreased agonist-induced internalization | PAF | [162] | |

| β-arrestin over G protein | ACKR3/CXCR4 | Inhibition of CXCL12-induced chemotaxis of lymphocytes, platelet activation, and thrombus formation Enhancement of colorectal tumorigenesis | CXCL12 dimers | [164,165] |

3.4. System Bias

System bias (Table 4) refers to differential signaling resulting from the biological system, e.g., variations in receptor density, different expression levels of transducers (G proteins, β-arrestins), and differences in downstream signaling machinery (kinases, scaffolding proteins, effectors) [167,168]. System bias is a form of natural bias that should be carefully considered when studying the effects of biased ligands, since differences in the experimental system may lead to contradictory and confusing results. Another critical point to consider in translational approaches is that system bias may differ in different species [169].

An example of system bias due to different expression levels of transducers is related to the D2 receptors. Ligands for the D2 dopamine receptor biased for β-arrestin 2 act as antagonists or agonists in the striatum or the prefrontal cortex, respectively. The differential expression of β-arrestins and GRKs across brain regions may be the reason [170,171,172]. The D1-selective agonist tavapadon is G protein-biased, acting as a partial agonist of Gαs and a full agonist of Gαolf. The latter is highly expressed in the striatum, and this may explain the significant effect of tavapadon in controlling Parkinson’s disease-related motor disorders. Gαs predominates in the prefrontal cortex, explaining the low efficacy of tavapadon in enhancing cognitive function [173]. Expressing different levels of Gα protein subunits in a controlled cellular system has provided further evidence that the G protein stoichiometry is crucial for the bias of β-adrenergic receptor agonists, affecting both their potency and efficacy [174].

An example of the significant role of the receptor density in biased signaling is the D2 dopamine receptor. By using an in vitro system and manipulating the expression levels of the D2 receptor, it was found that the partial D2 agonist aripiprazole preferentially activated β-arrestin 2 over Gαi1 at high D2 levels. In contrast, at low receptor levels, it preferentially activated Gαi1. Another D2 partial agonist, brexpiprazole, which has lower intrinsic activity compared to aripiprazole, showed bias for Gαi1 at high D2 receptor levels and β-arrestin 2 bias at low D2 receptor levels. Cariprazine, also a D2 partial agonist, demonstrated β-arrestin 2 bias irrespective of D2 receptor density [175].

Two other forms of system bias are temporal and spatial biases. Structurally different ligands may not alter effector activation, but rather change the duration of signaling (temporal bias) or the subcellular compartment (spatial or location bias) where signaling will take place. The compositional diversity of Gβγ subunits is considered one of the reasons for the spatial and temporal biased signaling of GPCRs; the activity of distinct combinations of Gβγ subunits leads to different kinetics and efficacy across subcellular compartments [59].

Spatial bias occurs when a GPCR in the presence of the same ligand triggers different downstream signaling pathways depending on the receptor’s subcellular location within the cell [10]. The development of advanced tools for high-resolution tracking of GPCRs has led to the realization that these receptors do not signal exclusively from the plasma membrane or the endosomes. Instead, GPCRs are found in all membranous organelles within cells, including the nucleus, and act as functional receptors that modulate signal transduction [10,18]. An example of spatial bias is observed in the case of FSHR with the A189V mutation, which, as discussed in Section 3.3, results in decreased expression at the plasma membrane. Data indicate that reduced plasma membrane levels of wild-type FSHR also elicit biased β-arrestin signaling [81], suggesting that biased signaling downstream of this mutation may also be categorized as system bias. Signaling elicited by GPCR activation in different intracellular compartments, as well as the underlying mechanisms involved, e.g., whether GPCRs translocate upon activation or reside in these compartments, remain incompletely understood. Here, we focus on a few examples where ligands that preferentially activate receptors at specific subcellular locations may have therapeutic advantages. For instance, in rat cardiac myocytes, β-adrenergic receptors that are localized on the Golgi and plasma membrane are activated independently of each other. Activation of the Golgi-localized receptors contributes to cardiac hypertrophy, and cell-penetrant β-blockers, such as metoprolol, are more efficacious than non-permeable drugs, e.g., sotalol, in such cases [176]. Endosomal GPCR signaling through G proteins also seems to be physiologically relevant. For example, endosomal substance P neurokinin 1 receptor (NK1R) signaling leads to sustained excitation of spinal neurons and pain transmission. Antagonists that reach the endosomal NK1R seem to be more effective analgesics than conventional plasma membrane–targeted antagonists [177]. Psychedelic substances act as 5-HT2A receptor agonists and promote cortical structural and functional neuroplasticity, but are hallucinogenic. Although the psychedelics’ hallucinogenic effects have been attributed to the activation of Gαq/11 downstream of the 5-HT2A receptor [116], their efficacy in promoting neuroplasticity is due to the activation of intracellular pools of the 5-HT2A receptor. Most 5-HT2A receptors in cortical neurons are localized to the Golgi and are activated by psychedelic substances that are lipophilic and easily diffuse through the plasma membrane. Serotonin does not cross the plasma membrane and acts solely on the plasma membrane receptors [178]. The metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR5 is involved in modulating neural signaling in both excitatory and inhibitory pathways and is a target for developing treatments for anxiety disorders and neurodegenerative diseases. mGluR5 is located at both the cell membrane and the nuclear membrane. Depending on its location, it activates different signaling pathways, and a membrane-permeable antagonist has been demonstrated to produce a greater analgesic effect compared to membrane-impermeable antagonists [179]. CB1 receptors are localized at both the plasma and mitochondrial membranes, and the genetic deletion specifically of the mitochondrial CB1 receptors in the hippocampus prevented cannabinoid-induced amnesia. Although there are no mitochondria-specific CB1 modulators up to date, these data support their development as potentially safer cannabinoid therapeutics [180].

Although data related to location bias are accumulating, the mechanisms governing intracellular GPCR signaling are mostly unknown. It was recently shown that GRKs contribute to location bias in GPCR signaling. For the CXCR3 receptor, it has been demonstrated that the impact of receptor location on G protein and β-arrestin signaling is ligand-specific, and activation of receptors at different locations has different functional outcomes and significance [181]. This seems to be due to distinct patterns of GRK recruitment to the plasma membrane or the endosomal CXCR3, depending on the agonist used to activate the receptor [182]. It was also demonstrated that the local environment determines the preferred active receptor conformation upon agonist binding. For example, the δ-opioid receptor is primarily localized in the Golgi, but also in the plasma membrane in neurons. By using conformational biosensors and high-resolution imaging, it was found that the same δ-opioid-selective receptor agonist activates distinct active conformations in each compartment that differentially couple to distinct effectors and produce distinct signaling responses [183].

Table 4.

Main mechanisms related to system bias. The text contains more details, and the table is not exhaustive of the relevant literature.

Table 4.

Main mechanisms related to system bias. The text contains more details, and the table is not exhaustive of the relevant literature.

| Reason | Bias | Location | Receptor | Ligand(s)/Effect | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Receptor density | β-arrestin over G protein | Cell membrane | D2 dopamine receptor | Aripiprazole at high receptor levels Brexpiprazole at low receptor levels Cariprazine at all receptor levels | [175] |

| G protein over β-arrestin | Cell membrane | D2 dopamine receptor | Aripiprazole at low receptor levels Brexpiprazole at high receptor levels | [175] | |

| Subcellular receptor localization | Unknown | Golgi | β-adrenergic receptor in cardiac myocytes | Cell-permeable metoprolol to prevent cardiac hypertrophy | [176] |

| β-arrestin over G protein | 5-HT2A receptors in cortical neurons | Lipophilic psychedelic substances promote neuroplasticity | [178] | ||

| G protein over β-arrestin | δ-opioid receptor | Distinct effectors and signaling responses | [183] | ||

| Unknown | Endosomes | NK1R in spinal neurons | Cell-permeable antagonists as effective analgesics | [177] | |

| CXCR3 | Biased signaling depending on the chemokine | [181,182] | |||

| Mitochondrial membrane | CB1 receptor in the hippocampus | Related to cannabinoid-induced amnesia | [180] | ||

| Nuclear membrane/nucleus | Neural mGluR5 | Cell-permeable antagonists for greater analgesia | [179] | ||

| G protein expression levels | ↑ Gαolf | Striatum | D1 dopamine receptor | Tavapadon in Parkinson’s | [173] |

| ↑ Gαs | Prefrontal cortex | D1 dopamine receptor | Tavapadon, but does not affect cognitive function | [173] | |

| β-arrestin expression levels | ↑ β-arrestin 2 | Prefrontal cortex | β-arrestin 2-biased D2 receptor ligands | Agonistic activity | [170,171,172] |

| ↓ β-arrestin 2 | Striatum | β-arrestin 2-biased D2 receptor ligands | Antagonistic activity | [170,171,172] |

4. Limitations Associated with Ligand Bias Investigation

Despite the discoveries and advances in the field of biased GPCR signaling and the enthusiasm surrounding this area of research, numerous limitations need to be addressed. One of the most critical aspects to consider when identifying ‘druggable’ ligand bias is to eliminate system and observation bias. Observation or assay bias is an artifact of the methodological approach, especially when signaling outputs are measured using assays with different sensitivities, dynamic ranges, and signal-to-noise ratios. Assay types and assay conditions can have a great impact on the interpretation of one effect as being biased. More traditional approaches for bias measurement used GTP/GDP exchange [35S]–GTPγS binding assay, mainly for detecting Gαs and Gαq signaling) or effectors downstream of the receptor, such as Ca2+ or IP3 levels. The main concept in the newer approaches, FRET and BRET, is that a fluorescent or bioluminescent energy donor bound to a GPCR interacts with a fluorescent or bioluminescent energy acceptor bound to effectors such as G proteins or β-arrestins. The energy transfer can be identified and analyzed when the distance, thus the interaction of the receptor and the effector, changes, giving a more precise indication of GPCR activation. Examples of such experiments yielding different outcomes depending on the assays used for GPCR activation exist in the literature [168]. These can be avoided using multiple, well-validated assays, where responses from both unbiased and biased ligands are compared in parallel [184]. Allosteric ligands, such as ions in the buffer used, as well as experimental conditions, such as temperature, pH, and osmolarity, can interfere with ligand binding and downstream outcomes [185]. Equally important is the questioning and investigation of whether data derived from a simple in vitro model can be translated to whole organs and body systems.

Another important aspect to consider is that studying the effect of ligands on GPCR signaling usually requires overexpression of the evaluated receptor. Since native cells behave differently from recombinant cells, the data generated thereby need to be handled with caution and further validated in appropriate contexts, i.e., primary cells, tissues, or animal models [69,186]. On this note, a recent study examining AT1R and its response to both unbiased angiotensin II and β-arrestin-biased agonists reported that in AT1R-overexpressing cells, β-arrestin-biased ligands lost their functional selectivity [186]. Similarly, elimination of selected G protein expression by utilizing CRISPR/Cas9 editing as a relatively new approach to identifying β-arrestin signaling readouts without the fear of G protein contribution may differ from the natural signaling pathways of the human body [187].

The sensitivity and specificity of the chosen functional assay can profoundly affect the determination of bias. An extra difficulty relates to the identification of β-arrestin signaling. This is because, in contrast to the G-protein-dependent signaling, which can be measured directly, readouts of β-arrestin signaling are ambiguous. Arrestin signaling is often measured indirectly, with parameters such as the internalization rate or ERK1/2 activation. These measurements are improper or insufficient because such procedures may or may not require arrestin activation (e.g., ERK1/2 activation can depend on both G protein and β-arrestin), making this readout more deceiving than helpful [69].

Ligand bias is recognized following comparison with an unbiased reference ligand, which is not always feasible to find. Endogenous agonists used as reference ligands may be biased themselves [188]. Moreover, GPCRs exist in a dynamic equilibrium between multiple conformations, including inactive and active states, even in the absence of a ligand. No ligand, including biased ligands, can shift this equilibrium completely to a single conformation, thus hardening the study of the mechanistic aspects of biased signaling, especially in vivo [65,69,189].

As a result of the discussed difficulties and due to the complexity of the signaling pathways, some reports challenge the notion of the β-arrestin bias concept, even related to the efficacy and safety profile of oliceridine [189].

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

In GPCR signaling, receptors can selectively couple with multiple G protein subtypes, engage different GRKs and other kinases, and recruit β-arrestins and other effectors. The goals of drug discovery targeting biased agonists focus on exploiting therapeutically relevant pathways while minimizing the impact from pathways linked to adverse effects. Meaningful evaluation of bias necessitates the appropriate context (relevant cells, tissues, in vivo models). Factors such as allosteric modulators, signaling bias, oligomerization, and signaling from different locations all contribute to GPCR functions, complicating the recognition and development of biased GPCR ligands. With the use of more sensitive experimental tools, recognition of the challenges involved in the field, and optimization of assays to overcome limitations, the development of more and reliably validated biased agonists will be facilitated. Another approach not discussed in this review, which relates to GPCRs that couple to multiple G proteins, is developing molecules that target specific G protein α or βγ subunits. Such molecules have been developed and demonstrate strong efficacy in numerous preclinical disease models for thrombosis, asthma, melanoma, opioid analgesia, chronic inflammatory disease, heart failure, fibrosis, and others [20]. Artificial intelligence is also being employed, and through numerous simulations and machine learning tools, is expected to facilitate the modeling of GPCR signaling and the prediction/analysis of ligand-induced biased signaling [190].

Author Contributions

N.G.L. conceptualized and prepared the first draft of this review as part of his MPharm diploma thesis. E.P. (Evangelia Pantazaka) organized and revised the manuscript. E.P. (Evangelia Papadimitriou) supervised the work, drafted the review, and formatted the final manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| 5-HT2A | 5-hydroxytryptamine 2A |

| AC | Adenylyl cyclase |

| ACKRs | Atypical chemokine receptors |

| AP2 | Adaptive protein 2 |

| aPC | Activated protein C |

| AR | Adrenergic receptor |

| AT1R | Angiotensin II type 1 receptor |

| BRET | Bioluminescence resonance energy transfer |

| CaS | Calcium sensing |

| CB1 | Cannabinoid 1 |

| CCR | CC chemokine receptor |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CXCR | CXC chemokine receptor |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| ERK | Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| FRET | Fluorescence resonance energy transfer |

| FSHR | Follicle-stimulating hormone receptor |

| GalR2 | Galanin receptor 2 |

| GLP1 | Glucagon-like peptide 1 |

| GPCRs | G protein-coupled receptors |

| GRKs | GPCR kinases |

| HCA3 | Hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 3 |

| LSD | Lysergic acid diethylamide |

| MC4R | Melanocortin−4 receptor |

| NK1R | Neurokinin 1 receptor |

| NTSR1 | Neurotensin receptor 1 |

| PAF | Platelet activation factor |

| PAR1 | Protease-activated receptor 1 |

| SNP | Single-nucleotide polymorphism |

| V2R | Vasopressin receptor 2 |

References

- Alexander, S.P.H.; Christopoulos, A.; Davenport, A.P.; Kelly, E.; Mathie, A.A.; Peters, J.A.; Veale, E.L.; Armstrong, J.F.; Faccenda, E.; Harding, S.D.; et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2023/24: G protein-coupled receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 180, S23–S144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slosky, L.M.; Caron, M.G.; Barak, L.S. Biased Allosteric Modulators: New Frontiers in GPCR Drug Discovery. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2021, 42, 283–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoneberg, T.; Liebscher, I. Mutations in G Protein-Coupled Receptors: Mechanisms, Pathophysiology and Potential Therapeutic Approaches. Pharmacol. Rev. 2021, 73, 89–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boutin, J.A.; Legros, C. The five dimensions of receptor pharmacology exemplified by melatonin receptors: An opinion. Pharmacol. Res. Perspect. 2020, 8, e00556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, I.; Ueda, T.; Kofuku, Y.; Eddy, M.T.; Wuthrich, K. GPCR drug discovery: Integrating solution NMR data with crystal and cryo-EM structures. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019, 18, 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odoemelam, C.S.; Percival, B.; Wallis, H.; Chang, M.W.; Ahmad, Z.; Scholey, D.; Burton, E.; Williams, I.H.; Kamerlin, C.L.; Wilson, P.B. G-Protein coupled receptors: Structure and function in drug discovery. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 36337–36348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pizio, A.; Levit, A.; Slutzki, M.; Behrens, M.; Karaman, R.; Niv, M.Y. Comparing Class A GPCRs to bitter taste receptors: Structural motifs, ligand interactions and agonist-to-antagonist ratios. Methods Cell Biol. 2016, 132, 401–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wang, Y.; Ni, H.; Yao, M.; Cheng, L.; Lin, X. The role of orphan G protein-coupled receptors in pain. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Shadangi, S.; Rana, S. G-protein coupled receptors in neuroinflammation, neuropharmacology, and therapeutics. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2025, 242, 117301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crilly, S.E.; Puthenveedu, M.A. Compartmentalized GPCR Signaling from Intracellular Membranes. J. Membr. Biol. 2021, 254, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, S.J.; Tobin, A.B. Design of Next-Generation G Protein-Coupled Receptor Drugs: Linking Novel Pharmacology and In Vivo Animal Models. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2016, 56, 535–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wacker, D.; Stevens, R.C.; Roth, B.L. How Ligands Illuminate GPCR Molecular Pharmacology. Cell 2017, 170, 414–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Martin, B.; Brenneman, R.; Luttrell, L.M.; Maudsley, S. Allosteric modulators of G protein-coupled receptors: Future therapeutics for complex physiological disorders. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009, 331, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, M.F.; Tampé, R. Ligand-independent receptor clustering modulates transmembrane signaling: A new paradigm. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2023, 48, 156–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marti-Solano, M.; Crilly, S.E.; Malinverni, D.; Munk, C.; Harris, M.; Pearce, A.; Quon, T.; Mackenzie, A.E.; Wang, X.; Peng, J.; et al. Combinatorial expression of GPCR isoforms affects signalling and drug responses. Nature 2020, 587, 650–656, Correction in Nature 2020, 588, E24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagi, K.; Onaran, H.O. Biased agonism at G protein-coupled receptors. Cell. Signal. 2021, 83, 109981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sriram, K.; Insel, P.A. G Protein-Coupled Receptors as Targets for Approved Drugs: How Many Targets and How Many Drugs? Mol. Pharmacol. 2018, 93, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammad Nezhady, M.A.; Rivera, J.C.; Chemtob, S. Location Bias as Emerging Paradigm in GPCR Biology and Drug Discovery. iScience 2020, 23, 101643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, W.; He, T.; Liao, J.; Qian, Z.; Zhao, J.; Cong, Z.; Sun, D.; Liu, Z.; et al. Genome-wide pan-GPCR cell libraries accelerate drug discovery. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2024, 14, 4296–4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A.P.; Smrcka, A.V. Targeting G protein-coupled receptor signalling by blocking G proteins. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2018, 17, 789–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gareri, C.; Rockman, H.A. G-Protein-Coupled Receptors in Heart Disease. Circ. Res. 2018, 123, 716–735, Correction in Circ. Res. 2018, 123, e34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calebiro, D.; Miljus, T.; O’Brien, S. Endomembrane GPCR signaling: 15 years on, the quest continues. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2025, 50, 46–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzen, E.; Ceraudo, E.; Berchiche, Y.A.; Rico, C.A.; Fürstenberg, A.; Sakmar, T.P.; Huber, T. G protein subtype-specific signaling bias in a series of CCR5 chemokine analogs. Sci. Signal. 2018, 11, eaao6152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Littmann, T.; Buschauer, A.; Bernhardt, G. Split luciferase-based assay for simultaneous analyses of the ligand concentration- and time-dependent recruitment of β-arrestin2. Anal. Biochem. 2019, 573, 8–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suno, R. Exploring Diverse Signaling Mechanisms of G Protein-Coupled Receptors through Structural Biology. J. Biochem. 2024, 175, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horioka, M.; Ceraudo, E.; Lorenzen, E.; Sakmar, T.P.; Huber, T. Purinergic Receptors Crosstalk with CCR5 to Amplify Ca2+ Signaling. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2021, 41, 1085–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Anderson, P.J.; Rajagopal, S.; Lefkowitz, R.J.; Rockman, H.A. G Protein-Coupled Receptors: A Century of Research and Discovery. Circ. Res. 2024, 135, 174–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raehal, K.M.; Bohn, L.M. β-arrestins: Regulatory role and therapeutic potential in opioid and cannabinoid receptor-mediated analgesia. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 2014, 219, 427–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, M.G.; Barak, L.S. A Brief History of the β-Arrestins. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 1957, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilardaga, J.P.; Jean-Alphonse, F.G.; Gardella, T.J. Endosomal generation of cAMP in GPCR signaling. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014, 10, 700–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahsai, A.W.; Shah, K.S.; Shim, P.J.; Lee, M.A.; Shreiber, B.N.; Schwalb, A.M.; Zhang, X.; Kwon, H.Y.; Huang, L.Y.; Soderblom, E.J.; et al. Signal transduction at GPCRs: Allosteric activation of the ERK MAPK by β-arrestin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2303794120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Tesmer, J.J.G. G protein-coupled receptor interactions with arrestins and GPCR kinases: The unresolved issue of signal bias. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 102279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maharana, J.; Sarma, P.; Yadav, M.K.; Saha, S.; Singh, V.; Saha, S.; Chami, M.; Banerjee, R.; Shukla, A.K. Structural snapshots uncover a key phosphorylation motif in GPCRs driving β-arrestin activation. Mol. Cell 2023, 83, 2091–2107.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry-Hauser, N.A.; Asher, W.B.; Hauge Pedersen, M.; Javitch, J.A. Assays for detecting arrestin interaction with GPCRs. Methods Cell Biol. 2021, 166, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dwivedi-Agnihotri, H.; Chaturvedi, M.; Baidya, M.; Stepniewski, T.M.; Pandey, S.; Maharana, J.; Srivastava, A.; Caengprasath, N.; Hanyaloglu, A.C.; Selent, J.; et al. Distinct phosphorylation sites in a prototypical GPCR differently orchestrate β-arrestin interaction, trafficking, and signaling. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabb8368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, A.I.; Perry, N.A.; Gurevich, V.V.; Iverson, T.M. Phosphorylation barcode-dependent signal bias of the dopamine D1 receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 14139–14149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhu, M.K.; Debroy, A.; Murarka, R.K. Molecular Insights into Phosphorylation-Induced Allosteric Conformational Changes in a β2-Adrenergic Receptor. J. Phys. Chem. B 2022, 126, 1917–1932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, E.H.; Abrol, R. Thermodynamic role of receptor phosphorylation barcode in cannabinoid receptor desensitization. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2025, 743, 151100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurevich, E.V.; Tesmer, J.J.; Mushegian, A.; Gurevich, V.V. G protein-coupled receptor kinases: More than just kinases and not only for GPCRs. Pharmacol. Ther. 2012, 133, 40–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Homan, K.T.; Vishnivetskiy, S.A.; Manglik, A.; Tesmer, J.J.; Gurevich, V.V.; Gurevich, E.V. G Protein-coupled Receptor Kinases of the GRK4 Protein Subfamily Phosphorylate Inactive G Protein-coupled Receptors (GPCRs). J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 10775–10790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kee, T.R.; Khan, S.A.; Neidhart, M.B.; Masters, B.M.; Zhao, V.K.; Kim, Y.K.; McGill Percy, K.C.; Woo, J.A. The multifaceted functions of β-arrestins and their therapeutic potential in neurodegenerative diseases. Exp. Mol. Med. 2024, 56, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moo, E.V.; van Senten, J.R.; Brauner-Osborne, H.; Moller, T.C. Arrestin-Dependent and -Independent Internalization of G Protein-Coupled Receptors: Methods, Mechanisms, and Implications on Cell Signaling. Mol. Pharmacol. 2021, 99, 242–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurevich, V.V.; Chen, Q.; Gurevich, E.V. Arrestins: Introducing Signaling Bias Into Multifunctional Proteins. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2018, 160, 47–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gesty-Palmer, D.; Luttrell, L.M. Refining efficacy: Exploiting functional selectivity for drug discovery. Adv. Pharmacol. 2011, 62, 79–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueras-Ortiz, C.; Yudowski, G.A. The Multiple Waves of Cannabinoid 1 Receptor Signaling. Mol. Pharmacol. 2016, 90, 620–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, B.L.; Chuang, D.M. Multiple mechanisms of serotonergic signal transduction. Life Sci. 1987, 41, 1051–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenakin, T. Agonist-receptor efficacy. II. Agonist trafficking of receptor signals. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1995, 16, 232–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luttrell, L.M. Minireview: More than just a hammer: Ligand “bias” and pharmaceutical discovery. Mol. Endocrinol. 2014, 28, 281–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guven, B.; Onay-Besikci, A. Past and present of beta arrestins: A new perspective on insulin secretion and effect. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 956, 175952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Su, C.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, H. Cryo-EM Structures and AlphaFold3 Models of Histamine Receptors Reveal Diverse Ligand Binding and G Protein Bias. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilger, D. The role of structural dynamics in GPCR-mediated signaling. FEBS J. 2021, 288, 2461–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, S.C.; Bouvier, M. Illuminating the complexity of GPCR pathway selectivity-advances in biosensor development. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2021, 69, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, R.H.J.; English, J.G. Advancements in G protein-coupled receptor biosensors to study GPCR-G protein coupling. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 180, 1433–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eiger, D.S.; Hicks, C.; Gardner, J.; Pham, U.; Rajagopal, S. Location bias: A “Hidden Variable” in GPCR pharmacology. Bioessays 2023, 45, e2300123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundmann, M.; Kostenis, E. Temporal Bias: Time-Encoded Dynamic GPCR Signaling. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2017, 38, 1110–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayser, C.; Melkes, B.; Derieux, C.; Bock, A. Spatiotemporal GPCR signaling illuminated by genetically encoded fluorescent biosensors. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2023, 71, 102384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, P.; Scharf, M.M.; Bermudez, M.; Egyed, A.; Franco, R.; Hansen, O.K.; Jagerovic, N.; Jakubik, J.; Keseru, G.M.; Kiss, D.J.; et al. Progress on the development of Class A GPCR-biased ligands. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 182, 3249–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Künze, G.; Isermann, B. Targeting biased signaling by PAR1: Function and molecular mechanism of parmodulins. Blood 2023, 141, 2675–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuho, I.; Skamangas, N.K.; Muntean, B.S.; Martemyanov, K.A. Diversity of the Gβγ complexes defines spatial and temporal bias of GPCR signaling. Cell Syst. 2021, 12, 324–337.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthees, E.S.F.; Filor, J.C.; Jaiswal, N.; Reichel, M.; Youssef, N.; D’Uonnolo, G.; Szpakowska, M.; Drube, J.; König, G.M.; Kostenis, E.; et al. GRK specificity and Gβγ dependency determines the potential of a GPCR for arrestin-biased agonism. Commun. Biol. 2024, 7, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tennakoon, M.; Senarath, K.; Kankanamge, D.; Ratnayake, K.; Wijayaratna, D.; Olupothage, K.; Ubeysinghe, S.; Martins-Cannavino, K.; Hebert, T.E.; Karunarathne, A. Subtype-dependent regulation of Gβγ signalling. Cell. Signal. 2021, 82, 109947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wootten, D.; Christopoulos, A.; Marti-Solano, M.; Babu, M.M.; Sexton, P.M. Mechanisms of signalling and biased agonism in G protein-coupled receptors. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 638–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oakley, R.H.; Laporte, S.A.; Holt, J.A.; Caron, M.G.; Barak, L.S. Differential affinities of visual arrestin, beta arrestin1, and beta arrestin2 for G protein-coupled receptors delineate two major classes of receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 17201–17210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanni, S.J.; Hansen, J.T.; Bonde, M.M.; Speerschneider, T.; Christensen, G.L.; Munk, S.; Gammeltoft, S.; Hansen, J.L. β-Arrestin 1 and 2 stabilize the angiotensin II type I receptor in distinct high-affinity conformations. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 161, 150–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gurevich, V.V.; Gurevich, E.V. Biased GPCR signaling: Possible mechanisms and inherent limitations. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 211, 107540, Correction in Pharmacol. Ther. 2020, 213, 107615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakami, K.; Yanagawa, M.; Hiratsuka, S.; Yoshida, M.; Ono, Y.; Hiroshima, M.; Ueda, M.; Aoki, J.; Sako, Y.; Inoue, A. Heterotrimeric Gq proteins act as a switch for GRK5/6 selectivity underlying β-arrestin transducer bias. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Schafer, C.T.; Mukherjee, S.; Wang, K.; Gustavsson, M.; Fuller, J.R.; Tepper, K.; Lamme, T.D.; Aydin, Y.; Agrawal, P.; et al. Effect of phosphorylation barcodes on arrestin binding to a chemokine receptor. Nature 2025, 643, 280–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motso, A.; Pelcman, B.; Kalinovich, A.; Kahlous, N.A.; Bokhari, M.H.; Dehvari, N.; Halleskog, C.; Waara, E.; de Jong, J.; Cheesman, E.; et al. GRK-biased adrenergic agonists for the treatment of type 2 diabetes and obesity. Cell 2025, 188, 5142–5156.e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenakin, T. Biased Receptor Signaling in Drug Discovery. Pharmacol. Rev. 2019, 71, 267–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, I.; Sierra, S.; Lueptow, L.; Gupta, A.; Gouty, S.; Margolis, E.B.; Cox, B.M.; Devi, L.A. Biased signaling by endogenous opioid peptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 11820–11828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaVigne, J.; Keresztes, A.; Chiem, D.; Streicher, J.M. The endomorphin-1/2 and dynorphin-B peptides display biased agonism at the mu opioid receptor. Pharmacol. Rep. 2020, 72, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, G.L.; Lane, J.R.; Coudrat, T.; Sexton, P.M.; Christopoulos, A.; Canals, M. Biased Agonism of Endogenous Opioid Peptides at the μ-Opioid Receptor. Mol. Pharmacol. 2015, 88, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, Z.; Shen, Q.; Yao, B.; Mao, C.; Chen, L.N.; Zhang, H.; Shen, D.D.; Zhang, C.; Li, W.; Du, X.; et al. Identification and mechanism of G protein-biased ligands for chemokine receptor CCR1. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2022, 18, 264–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Liu, Y.; Zaidi, S.A.; Xu, L.; Zhan, Y.; Chen, A.; Guo, J.; Huang, X.P.; Roth, B.L.; Katritch, V.; et al. Structural insights into angiotensin receptor signaling modulation by balanced and biased agonists. EMBO J. 2023, 42, e112940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szakadáti, G.; Tóth, A.D.; Oláh, I.; Erdélyi, L.S.; Balla, T.; Várnai, P.; Hunyady, L.; Balla, A. Investigation of the fate of type I angiotensin receptor after biased activation. Mol. Pharmacol. 2015, 87, 972–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galandrin, S.; Denis, C.; Boularan, C.; Marie, J.; M’Kadmi, C.; Pilette, C.; Dubroca, C.; Nicaise, Y.; Seguelas, M.H.; N’Guyen, D.; et al. Cardioprotective Angiotensin-(1-7) Peptide Acts as a Natural-Biased Ligand at the Angiotensin II Type 1 Receptor. Hypertension 2016, 68, 1365–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Alcaraz, A.; Lee, Y.N.; Yun, S.; Hwang, J.I.; Seong, J.Y. Conformational signatures in β-arrestin2 reveal natural biased agonism at a G-protein-coupled receptor. Commun. Biol. 2018, 1, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, A.R.; Hvidtfeldt, M.; Brauner-Osborne, H. Biased agonism of the calcium-sensing receptor. Cell Calcium 2012, 51, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]