1. Background

Trauma injury scoring systems are pivotal in the management of trauma patients, facilitating standardized assessments, guiding treatment decisions, and predicting outcomes [

1]. Trauma scoring systems have evolved to improve the assessment and management of injured patients [

1]. They provide a structured way to evaluate the severity of trauma, guide clinical decisions, and predict patient outcomes [

1]. Commonly used trauma scores include the Injury Severity Score (ISS), Revised Trauma Score (RTS), and Trauma and Injury Severity Score (TRISS). The ISS is anatomically based and assesses trauma severity by summing the squares of the Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) scores for the three most severe injuries [

2]. It is widely used, but has limitations in early, pre-hospital settings [

2]. The RTS combines physiological parameters such as the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), systolic blood pressure (SBP), and respiratory rate [

3]. It is useful for triage, but can be complex, and requires several parameters [

3]. Integrating ISS and RTS values along with patient age, TRISS calculates the probability of survival [

4]. It provides comprehensive outcome predictions but can be resource-intensive [

4].

The MGAP score addresses some complexities by utilizing minimal, yet crucial parameters, namely, mechanism of injury (M), Glasgow Coma Scale (G), age (A), and arterial pressure (P) [

1]. Sartorius et al. introduced the MGAP score, highlighting its benefits in pre-hospital and emergency settings due to its simplicity and rapid applicability [

1]. Mechanism of injury considers whether the injury was blunt or penetrating, significantly impacting the score [

1]. Blunt injuries often carry different prognoses and require different management approaches than penetrating injuries [

1]. As a neurological assessment tool, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is a central component of the MGAP score [

5]. It helps in evaluating the consciousness level of the patient, which correlates with trauma severity and potential outcomes [

5]. Incorporating age accounts for physiological resilience, which can influence trauma outcomes significantly [

6]. Lastly, blood pressure (BP) is a critical indicator of cardiovascular stability [

7]. The MGAP score uses arterial pressure to predict hemodynamic status and potential resuscitation requirements [

1].

The MGAP score requires minimal data collection, making it practical in situations with limited resources, such as pre-hospital settings. Its implementation facilitates rapid triage, aiding in decisions about hospital transport urgency and level of care required [

8]. Studies comparing MGAP with other scores often highlight its balance of simplicity and effectiveness, particularly in pre-hospital and emergency scenarios, where time and resources may be limited [

9]. This is particularly useful in low–middle-income countries (LMIC). The MGAP score has been validated in various studies, demonstrating reliable predictions of mortality and morbidity [

1,

10]. It performs particularly well in identifying patients at low risk of mortality, thus optimizing resource allocation and treatment prioritization [

11].

In LMICs, healthcare systems face challenges such as limited resources, long prehospital times, and underdeveloped infrastructure [

12,

13,

14]. The MGAP score is particularly advantageous in these settings due to its simplicity, reliance on easily obtainable parameters, and strong predictive ability. It supports early triage at the point of injury and enables efficient resource use upon hospital arrival. Over time, routine MGAP data collection can aid in health system planning and trauma policy development.

Given its predictive power for mortality, the MGAP score aids in triaging patients effectively. This is particularly beneficial in emergency situations, where patient influx may exceed available resources [

15]. By identifying patients with lower scores who are at higher risk, healthcare systems can prioritize critical care resources such as intensive care unit (ICU) beds and surgical interventions for those most in need [

16]. Conversely, patients with higher MGAP scores, indicating lower risk, can potentially be managed with less intensive resources or through outpatient care, optimizing overall resource use [

16].

In LMICs, prehospital care can be underdeveloped, with long transportation times and limited prehospital interventions [

17]. The MGAP score can be applied rapidly in prehospital settings to determine the urgency and type of facility to which patients should be directed, ensuring that those who require immediate and intensive care reach appropriate facilities faster [

17,

18]. This can improve survival rates by reducing delays in receiving definitive care [

18]. The MGAP score’s straightforwardness makes it an advantageous choice for training personnel in LMICs [

19]. Training programmes can integrate the score into the curricula for both prehospital and emergency medical staff, potentially improving the standardization of trauma care and enabling more consistent application of triage protocols across different regions and facilities [

20].

Using the MGAP score helps accumulate data on trauma outcomes, which can be valuable for regional health assessments and strategic planning [

20,

21]. Over time, collecting and analyzing data based on MGAP scores can inform healthcare policy and resource distribution, enabling health systems to identify trends, deploy resources more effectively, and improve trauma care guidelines [

22,

23].

South Africa, like many other LMICs, faces a high burden of trauma, driven by factors such as motor vehicle accidents, interpersonal violence, and penetrating injuries. In such settings, the ability to rapidly and accurately triage patients is crucial for optimizing the use of limited resources and improving patient outcomes. Therefore, the MGAP score’s ease of use, coupled with its capability to make rapid, reliable predictions about trauma severity and outcomes, makes it an excellent tool for optimizing trauma care in LMICs. By facilitating efficient triage and resource allocation, as well as offering practical training potential, MGAP can contribute significantly to improving trauma patient management where resources are constrained.

This study aims to determine the association between the MGAP score and mortality in trauma patients presenting to the trauma emergency unit (TEU) of a hospital in a resource-limited setting such as Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital (CHBAH). The findings of this study will contribute to the growing body of evidence supporting the use of the MGAP score as a valuable tool for improving trauma care in LMICs.

Purpose

To determine if there is an association between the MGAP scoring system and initial mortality outcomes in trauma patients presenting to the trauma emergency unit. The objective is to determine the distribution of MGAP scores among trauma patients presenting to the TEU.

2. Methodology

This study comprises a retrospective record review of the resuscitation area of TEU of CHBAH. This study was conducted at the Trauma Emergency Unit (TEU) of Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital (CHBAH) in Soweto, Johannesburg. CHBAH is one of the largest public hospitals in the world. The hospital has approximately 3400 beds and serves a large and diverse catchment area, including both urban and rural communities with predominantly low-income populations. The TEU is a high-volume trauma centre. The TEU is staffed by a multidisciplinary team of doctors, nurses, and other healthcare professionals and has access to a CT scanner, operating theatres, and intensive care unit beds. The inclusion criteria were all priority 1 (P1) patients aged 18 years or older seen in the TEU within the data collection period from 1 January 2022 to 31 December 2022. The relevant data were collected from the CHBAH TEU resuscitation register with the following information to be extracted: age, sex, mechanism of injury, blood pressure (BP), and Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS). The outcome was survival or death within the resuscitation area at the TEU.

The data of all the patients was stored in a datasheet using Microsoft Excel and anonymized with a number system; confidentiality was maintained strictly by using an assigned patient number. The completed data collection sheets were kept safe by the primary investigator in a computer which was password-protected.

Ethical Consideration

The Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) (Medical) of the University of Witwatersrand approved this study (M250344). Patient confidentiality was maintained during the data collection process with all data records assigned a record number, and no identifying information was used.

3. Results

A total of 1983 P1 trauma cases were reviewed during the study period. Of these, 763 patients were excluded due to missing data (mechanism of injury, GCS, age, or blood pressure), resulting in a final sample size of 1220 patients included for MGAP analysis.

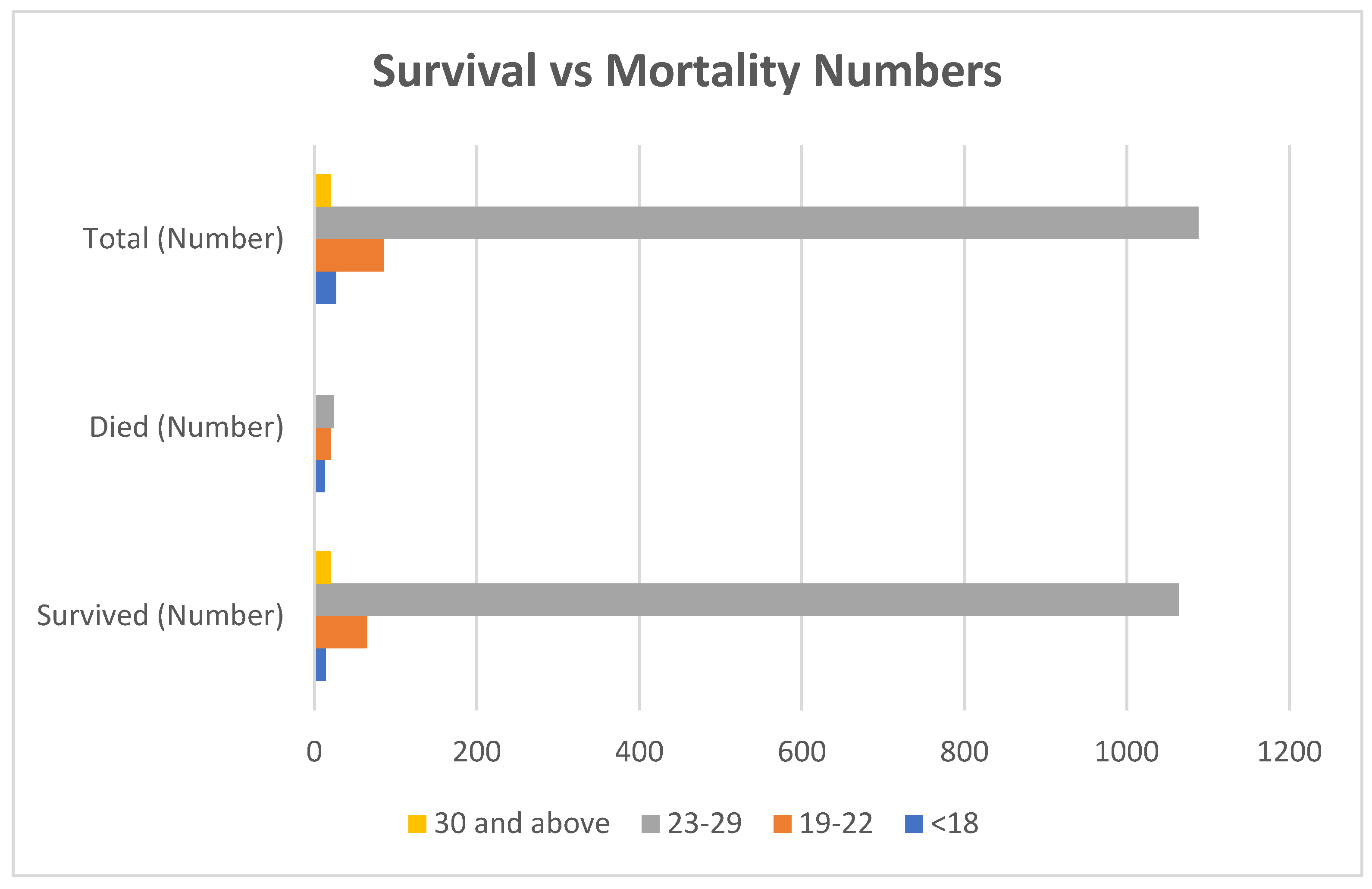

As demonstrated in

Table 1, high-risk (≤18): this group has a substantially higher mortality rate (48.1%), indicating the MGAP score effectively identifies patients at significant risk. Intermediate-risk (19–22): in this group, the mortality rate is lower (23.5%) compared to the high-risk group, suggesting effective risk stratification. Low-risk (23–29): the mortality rate is significantly low (2.2%), demonstrating the MGAP score’s ability to identify patients with a favourable prognosis. As evidenced in

Figure 1, very-low-risk (30 and above): this group had zero mortality, suggesting the MGAP score accurately classifies patients with an extremely low risk of death.

Table 2 compares the MGAP scores according to mortality; the Mann–Whitney U test (due to the non-normal distribution of MGAP scores) showed a

p-value of 2.2 × 10

−16, demonstrating a statistically significant (

p < 0.0001) value. There is a statistically significant difference in MGAP scores between patients who survived and those who died. Lower MGAP scores are associated with higher mortality.

When analyzing the association between the GCS score and mortality, the Mann–Whitney U test (due to the non-normal distribution of GCS scores) showed a p-value of 3.142 × 10−13, which is statistically significant (p < 0.0001). There is a statistically significant difference in GCS scores between patients who survived and those who died. Lower GCS scores are associated with higher mortality. MOI had a chi-square of 0.7681, which was not statistically significant.

Looking at the systolic BP and mortality, the Mann–Whitney U test (due to non-normal distribution of systolic BP) once again was statistically significant (p < 0.05), with a p-value of 0.0001174. There is a statistically significant difference in systolic BP between patients who survived and those who died. Lower systolic BP is associated with higher mortality.

Lastly, in

Table 3, the mechanism of injury and mortality when utilizing the chi-square test had a

p-value of 0.7681; therefore, it was not statistically significant (

p > 0.05). There is no statistically significant association between the mechanism and mortality.

Therefore, in summary, there is a strong inverse correlation as the MGAP scores increase, which indicates lower risk, and then mortality decreases significantly. This suggests that the MGAP score is a good predictor of survival.

Similarly to MGAP, there is an inverse correlation that the lower GCS scores, which indicate more severe neurological impairment, are associated with higher mortality. This aligns with the understanding that neurological status is critical for survival. In inverse correlation, lower systolic blood pressure is associated with higher mortality; once again, this highlights the importance of maintaining adequate perfusion for survival.

However, no significant association was found when comparing the mechanism of injury to mortality. This suggests that, in this dataset, the type of injury mechanism does not significantly predict mortality on its own. However, it is important to consider that specific injury mechanisms might still influence outcomes indirectly through their impact on MGAP, GCS, or systolic BP.

The Mann–Whitney U test was used for continuous variables (MGAP, GCS, SBP) due to their non-normal distribution, while the chi-square test assessed the association between mechanism of injury and mortality. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Additionally, to evaluate the predictive performance of the MGAP score compared to the Revised Trauma Score (RTS), a ROC curve analysis was conducted. The MGAP score demonstrated a superior area under the curve (AUC) of 0.89 (95% CI: 0.84–0.93), compared to an AUC of 0.82 (95% CI: 0.77–0.88) for RTS. This suggests that MGAP has better discriminative power in predicting mortality in this cohort. These findings support MGAP’s clinical utility, particularly in LMICs, where rapid, accessible scoring systems are crucial.

4. Discussion

This study investigated the association between the MGAP score and mortality in trauma patients presenting to a trauma emergency unit (TEU) in a resource-limited setting. The findings demonstrate a strong inverse correlation between MGAP score and mortality risk, supporting the notion that this simple, readily available scoring system is a valuable tool for risk stratification in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Our analysis revealed a clear gradient of mortality risk across MGAP score ranges. The highest mortality rate (48.1%) was observed among patients in the highest-risk group (MGAP score ≤ 18). This group, characterized by low systolic blood pressure, low GCS, and potentially older age, clearly presents a significant challenge in terms of management. The intermediate-risk group (MGAP score 19–22) exhibited a markedly lower, yet still significant, mortality rate (23.5%), highlighting the importance of early identification of this group for timely intervention. Importantly, the low-risk group (MGAP score 23–29) showed a substantially reduced mortality rate of only 2.2%. Patients with MGAP scores above 30 showed no mortality in this study.

These findings align with the original development and validation of the MGAP score by Sartorius et al. [

1], who highlighted its benefits in pre-hospital and emergency settings due to its simplicity and rapid applicability. The MGAP score’s reliance on readily available parameters—mechanism of injury, GCS, age, and arterial pressure—makes it particularly useful in resource-constrained environments where advanced diagnostic tools and specialized personnel may be scarce [

12,

13].

The analysis of the trauma patient data reveals statistically significant associations between patient outcomes (survival vs. death) and several key factors: MGAP score, GCS score, and systolic blood pressure. Lower MGAP scores, indicative of more severe trauma, are linked to higher mortality rates. Similarly, lower GCS scores, reflecting a decreased level of consciousness, are also associated with increased mortality. This is consistent with the established role of the GCS as a central component in assessing the consciousness level of trauma patients and its correlation with trauma severity and potential outcomes [

5]. Reduced systolic blood pressure is another significant predictor of mortality in this dataset.

However, the mechanism of injury, as categorized in this data, does not show a statistically significant relationship with patient survival. This contrasts with the MGAP score’s original design, where the mechanism of injury (blunt vs. penetrating) impacts the score [

1]. It is possible that in this specific patient population, other factors have a more dominant influence on mortality, or the categorization of injury mechanism was not granular enough to capture meaningful differences.

These results suggest that the MGAP score can effectively stratify trauma patients into distinct risk categories, allowing for the efficient allocation of limited resources in LMIC settings. The high mortality rate in the high-risk group emphasizes the need for targeted interventions, such as immediate resuscitation, prompt surgical intervention (where applicable), and close monitoring in intensive care units, if available. The identification of intermediate-risk patients provides an opportunity for early intervention to prevent deterioration and improve survival rates. The low-risk group can be managed with less intensive care, freeing up resources for those with higher acuity. This triage capability is particularly valuable in emergency situations where patient influx may exceed available resources [

15].

The MGAP score’s straightforwardness makes it an advantageous choice for training personnel in LMICs [

19]. Training programmes can integrate the score into the curricula for both prehospital and emergency medical staff, potentially improving the standardization of trauma care and enabling more consistent application of triage protocols across different regions and facilities [

20]. Using the MGAP score helps accumulate data on trauma outcomes, which can be valuable for regional health assessments and strategic planning [

20,

21]. Over time, collecting and analyzing data based on MGAP scores can inform healthcare policy and resource distribution, enabling health systems to identify trends, deploy resources more effectively, and improve trauma care guidelines [

22,

23].

The relevance of the MGAP score is particularly pronounced in LMICs like South Africa, where resource constraints often present significant challenges to trauma care. South Africa faces a high burden of trauma, driven by factors such as motor vehicle accidents, interpersonal violence, and penetrating injuries [

7,

8]. In such settings, the ability to rapidly and accurately triage patients is crucial for optimizing the use of limited resources and improving patient outcomes. The MGAP score’s simplicity and reliance on readily available parameters make it well-suited for use in under-resourced environments, where access to advanced diagnostic tools and specialized personnel may be limited. By facilitating efficient triage and resource allocation, the MGAP score can contribute to improved trauma patient management and potentially reduce mortality rates in LMICs, like South Africa. Further research is needed to validate the MGAP score’s performance in diverse LMIC settings and to explore its potential for integration into national trauma care guidelines.

Limitations

It is crucial to acknowledge the limitations of this study. The small sample sizes, particularly in certain MGAP score ranges, could affect the precision of mortality rate estimations. Additionally, this study’s reliance on a single, relatively small dataset limits the generalizability of findings. The presence of missing data in age and systolic blood pressure could introduce biases and needs to be addressed in future research.

Moreover, the MGAP score, while simple, does not encompass all relevant factors affecting trauma patient mortality. Other clinical parameters like the presence of other injuries, co-morbidities, and access to specialized care can significantly influence outcomes. A longer follow-up of patients during their admission, such as 48 h and 30-day intervals, may be able to improve the validity of the survival and mortality outcomes.

5. Conclusions

This study provides compelling evidence that the MGAP score is a valuable tool for assessing outcome predictions in trauma patients presenting to a trauma emergency unit in a resource-limited setting. The analysis of trauma patient data demonstrates a statistically significant inverse correlation between MGAP score and mortality, reinforcing the score’s ability to stratify patients into distinct risk categories. Lower MGAP scores, indicative of more severe trauma, were consistently associated with higher mortality rates, highlighting the critical role of the MGAP score in identifying high-risk patients who require immediate and intensive care.

These findings align with previous research on the MGAP score and its utility in pre-hospital and emergency settings, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) where resource constraints pose significant challenges to trauma care. The MGAP score’s simplicity and reliance on readily available parameters—mechanism of injury, GCS score, age, and systolic blood pressure—make it well-suited for use in under-resourced environments, where access to advanced diagnostic tools and specialized personnel may be limited.

While the mechanism of injury, as categorized in this study, did not show a statistically significant association with mortality, the MGAP score on the whole demonstrated a strong predictive capability. This suggests that the MGAP score effectively integrates the individual components to provide a comprehensive assessment of patient risk. The implications of these findings are particularly relevant for LMICs like South Africa, where the burden of trauma is high and resources are often scarce. The MGAP score can facilitate efficient triage and resource allocation, enabling healthcare providers to prioritize critical care resources for those most in need and potentially improve patient outcomes.

In conclusion, this study provides further support for the use of the MGAP score as a valuable tool for improving trauma care in resource-limited settings. By facilitating efficient triage, optimizing resource allocation, and guiding clinical decision-making, the MGAP score has the potential to contribute to reduced mortality rates and improved outcomes for trauma patients in LMICs.

Recommendations

Implementation of the MGAP score in trauma triage protocols: healthcare facilities in LMICs should consider incorporating the MGAP score into their trauma triage protocols to facilitate rapid and accurate risk assessment.

Training and education: healthcare providers, including those with basic training, should receive training and education on the use of the MGAP score to ensure consistent and reliable application.

Further research: future research should focus on validating the MGAP score’s performance in diverse LMIC settings, exploring its potential for integration into national trauma care guidelines, and investigating the impact of MGAP score implementation on patient outcomes.

In addition to validating the MGAP score in diverse LMIC settings, future studies should include prospective data collection to confirm the findings of this retrospective analysis and to assess the impact of MGAP score implementation on patient outcomes.

Data collection and analysis: healthcare systems should collect and analyze data based on MGAP scores to inform healthcare policy, resource distribution, and quality improvement initiatives.