1. Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) has emerged as a major global public health issue. The World Health Organization reports that CKD currently affects nearly 850 million people [

1].

Furthermore, CKD was ranked as the 27th leading cause of death worldwide in 1990, increasing to the 11th by 2016 [

2]; projections suggest it could become the 5th leading cause of death by 2040 [

3]. In Europe, approximately 100 million individuals are estimated to be living with CKD [

4]. Around 6 million people in France suffer from end-stage renal disease (ESRD), with over 90,000 undergoing treatment [

5].

The incidence rate of treated ESRD stands at 169 per million population, with rates 2.2 times higher in the overseas departments compared to mainland France [

6]. The rising global prevalence of diabetes, obesity, and hypertension over recent decades has contributed significantly to the surge in CKD reported in numerous epidemiological studies. This increase has led to more patients requiring dialysis and a growing demand for kidney transplantation (KT) worldwide [

7,

8,

9].

In Guadeloupe, KT has been performed since June 2004 [

10], with steady expansion until the end of 2019. However, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 disrupted healthcare systems worldwide [

11]. In France, a 25% decrease in organ transplants was observed compared to 2019, which was largely due to reduced organ procurement and the saturation of intensive care units [

12]. Guadeloupe was no exception: the partial suspension of transplant activities significantly impacted the care pathways of patients with kidney failure, exposing them to increased morbidity and mortality.

The last decade also coincides with an expansion of access criteria for kidney transplantation. Indeed, recently, studies conducted in the West and North America have reported a greater proportion of transplants with expanded criteria, or even ABO-incompatible transplants [

13,

14].

This paradigm shift responds to the need to address the graft shortage and the aging of the population. To date, in Guadeloupe, no study has compared the profile of transplant recipients and their survival according to these two periods. The cessation of transplant activity and its resumption at the University Hospital of Guadeloupe provided the opportunity to conduct this work. The objective of this study was to characterize the clinical profiles and survival outcomes of KT recipients at the University Hospital of Guadeloupe, comparing the periods before and after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

For the purposes of this study, and consistent with national data from mainland France, we defined the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in Guadeloupe as 1 March 2020, corresponding to the first officially reported cases and the implementation of public health measures in the French territories.

4. Discussion

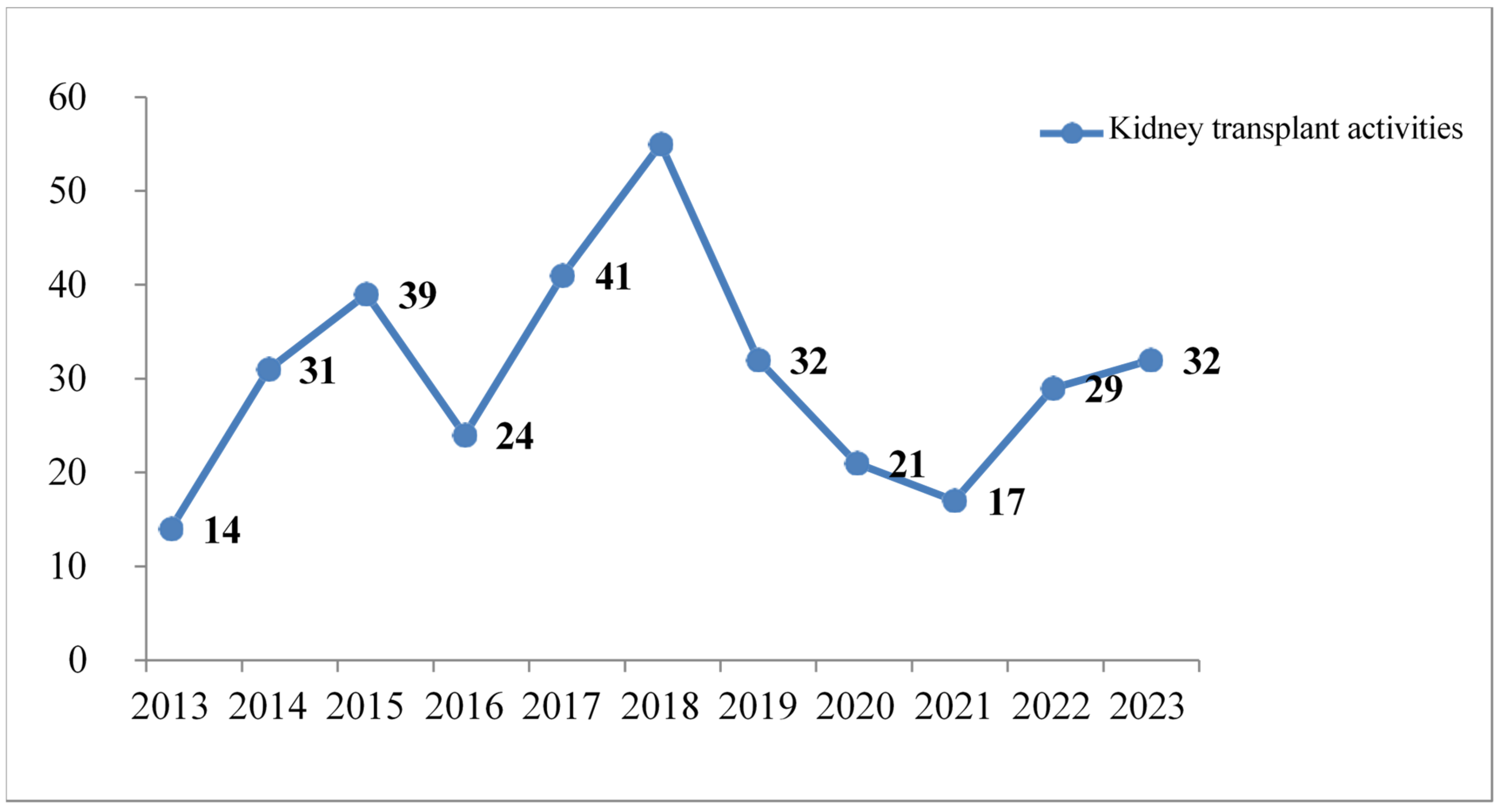

A total of 335 patients received KT during the study period. While KT activity gradually increased until 2018, it decreased again between 2019 and 2021. The Agence de la Biomédecine (ABM) confirmed this observation in France in its 2020 transplant activity report [

11].

The decrease in KT activity is primarily attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic, during which hospitals focused their efforts on patients with severe forms of the disease [

12].

In the present study, the average age of KT donors was 51.5 ± 16.1 years. This observation is consistent with data from metropolitan France [

11]. However, due to the shortage of grafts, the use of elderly donors is becoming increasingly frequent [

11]. Almost all the donors were DBD, i.e., 98.2 This quantity corresponds to only 1.8% of voluntary LRDs.

This proportion of LRDs is lower than the general average for transplant centers in France and in several other countries [

11]. Despite the first successful kidney transplant in Guadeloupe in 2004, many challenges remain. Very few people agree to donate a kidney; the rate of opposition to kidney donation is estimated at 50% in the Guadeloupean population, compared with 33% in France [

11]. To address this issue, the transplant coordination team at the CHU de Guadeloupe regularly organizes awareness-raising days to highlight the importance of live organ donation in saving lives. There are sex differences in the KT donation.

A multicenter study overseen by the European Committee on Organ Transplantation reported that men were the main source of DBMs, with proportions ranging from 63.3% to 71.9% in over 60 countries [

15]. In contrast, women represented the main source of kidneys from LRDs, accounting for 61.1%. In line with data from the general population, the three most common blood groups among KT donors were O, A, and B. The proportion of group O donors rose from 48.7% between 2013 and 2019 to 52.5% between 2020 and 2023. This increase has little impact, as the Rhesus group is not involved in organ transplantation.

The average age of patients was 52.5 ± 11.9 years (range: 22–81 years). The proportion of patients over 70 had risen from 2.1% over the period 2013 to 2019 to 8.1% from 2020 to 2023. Advanced age may be a limitation to renal transplantation; however, older patients with fewer comorbidities and fewer vascular complications may be eligible for renal transplantation. The average age of patients at the time of KT is comparable to the average reported in France [

11].

In many countries, the majority of harvested organs are transplanted into men rather than women [

16]. In our study, approximately two-thirds of transplant patients were male. This proportion had fallen over the period 2020 to 2023 compared with 2013 to 2019 (55.6% versus 67.4%), possibly reflecting easier access to healthcare services for women.

In terms of comorbidities, hypertension was preeminent, followed by diabetes mellitus and obesity, with proportions of 97.6%, 25.4%, and 17.6%, respectively. This result reflects the importance of these pathologies in the epidemiology of CKD. Hypertension, diabetes, and obesity are the top three cardiovascular risk factors for CKD, both in Guadeloupe and worldwide [

1,

2,

3].

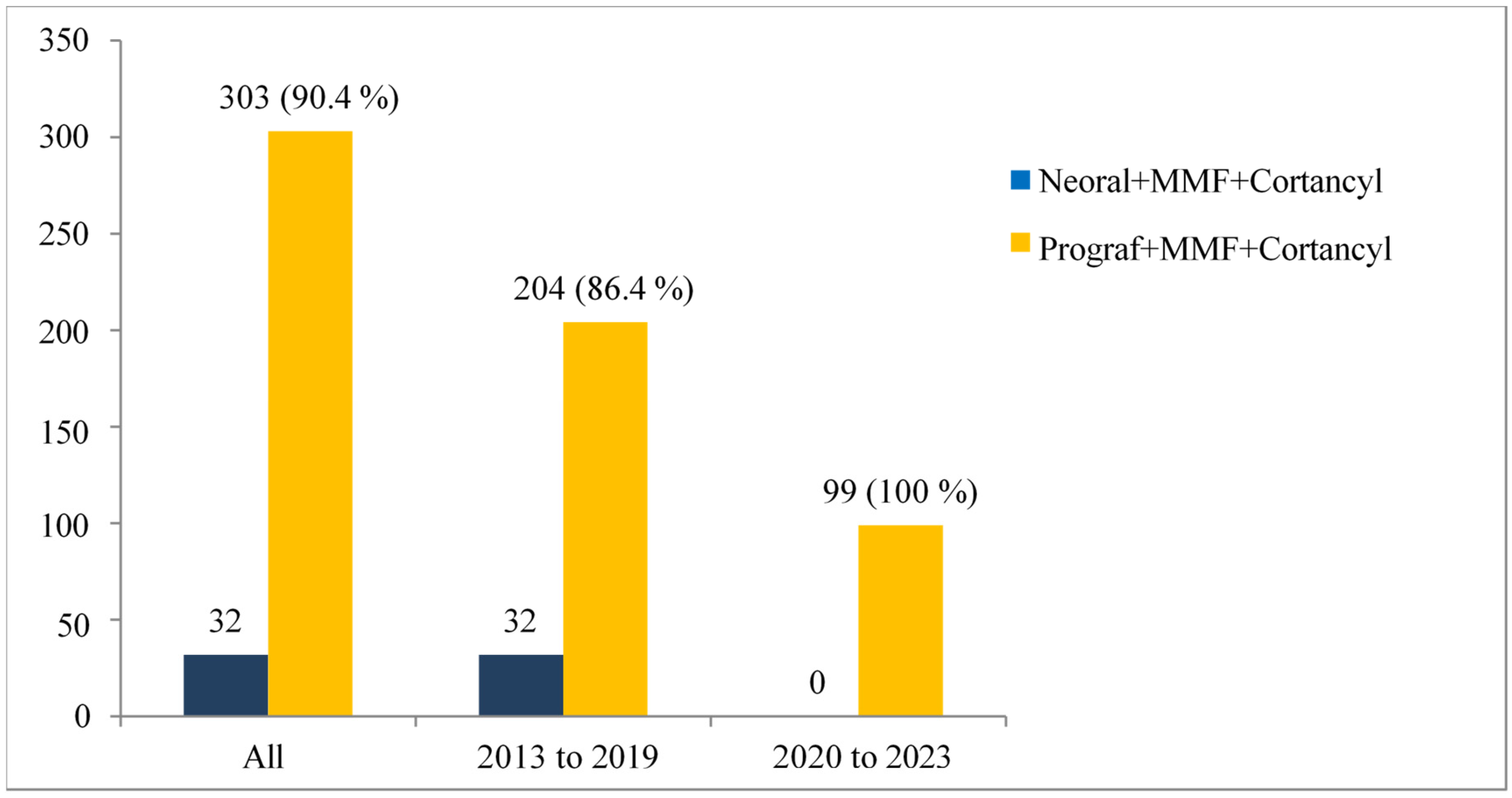

Between 2020 and 2023, the proportion of transplant patients who were obese, had heterozygous sickle cell disease, had polycystic kidney disease, had a history of blood transfusion, and tested positive for class I and II anti-HLA antibodies increased significantly.

Access to renal transplantation has become easier despite these comorbidities, thanks to the implementation of close and effective follow-up programs. For example, obese patients can benefit from bariatric surgery, gastric banding, or gastric bypass to reduce their weight and facilitate renal transplant surgery [

17].

For immunized patients, renal transplantation is no longer an absolute contraindication, as desensitization protocols and more effective immunosuppressive treatments with fewer adverse effects are now available [

18].

The terms of the transplant included several conditions that donors and recipients had to comply with. In the present study, all transplanted patients benefited from KTs with a compatible donor. All virtual and real crossmatch tests were negative. To date, ABO incompatible kidney transplants are not performed in Guadeloupe. This modality could help reduce waiting times for KTs, particularly for candidates from minority blood groups.

In France, the average waiting time for KTs with DBD is 17.2 months; however, in Guadeloupe, it is two to three times longer than in some regions of mainland France [

11].

According to the renal transplant activity report published by the ABM [

11], the average CIT has fallen from 15.4 h in 2013 to 12.4 h in 2023 throughout France.

For locally allocated transplants in Guadeloupe and Reunion, CIT had decreased from 17.1 h to 14.3 h for DBD [

11,

19]. Our results also indicate that CIT decreased significantly between the two study periods (1126.6 ± 392.3 min vs. 1002.9 ± 402.5 min). Longer CIT is known to be associated with delayed recovery of renal function and is a risk factor for graft failure [

20]. Strengthening logistical capacities and technical skills, as well as the introduction of an hourly tracking sheet for KTs, certainly helped us achieve the reduction in CIT during the second part of our study.

Our study did not specifically examine the possibility of fewer transplants from mainland France between 2020 and 2023.

Cold ischemia, a cornerstone of graft preservation, is associated with significant biochemical changes, including reduced adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production. The persistence of anaerobic glycolysis produces lactate, which generates acidosis with mediocre and inadequate energy production yield [

20,

21]. Organ cooling, while necessary, negatively impacts tissues by disrupting several metabolic pathways. For example, inhibition of the Na+/K+ ATPase pump leads to cellular and interstitial edemas, as well as disturbances in calcium homeostasis, which activate proteases and promote proteolytic lesions [

21].

All the grafts in our study were preserved with IGL-1

® solution, a new-generation preservation solution. Its colloid is a 35,000-dalton polyethylene glycol [

22]. Multicenter clinical results in KT patients showed that this solution resulted in better recovery of graft function and graft survival compared to grafts preserved with Belzer’s solution (UW), which has been recognized as the reference preservation solution in organ procurement for many years [

23].

Paradoxically, instead of decreasing, WIT actually increased during the second part of the present study (57.7 ± 17.8 min vs. 66.9 ± 21.5 min). Warm ischemia is also an important parameter of ischemia–reperfusion in transplantation, as it integrates the time taken to make graft anastomoses at the recipient’s body temperature. The prolonged duration of WIT induces cellular disorders responsible for kidney graft dysfunction [

20,

21].

Reasons that may explain our results include the introduction of new surgeons to the renal transplant unit, as well as a higher proportion of recipients aged 70 years or older, those who are obese, heterozygous sickle cell patients, and polycystic patients between 2020 and 2023. Comorbidities can promote atherosclerotic lesions, which may contribute to longer vascular anastomosis times.

In general, very few post-renal transplant complications were reported, both in 2013–2019 and 2020–2023. This low complication rate can be attributed to the fact that renal transplant practice at the CHU de Guadeloupe dates back to 2004, and the teams are better trained and have acquired experience [

5].

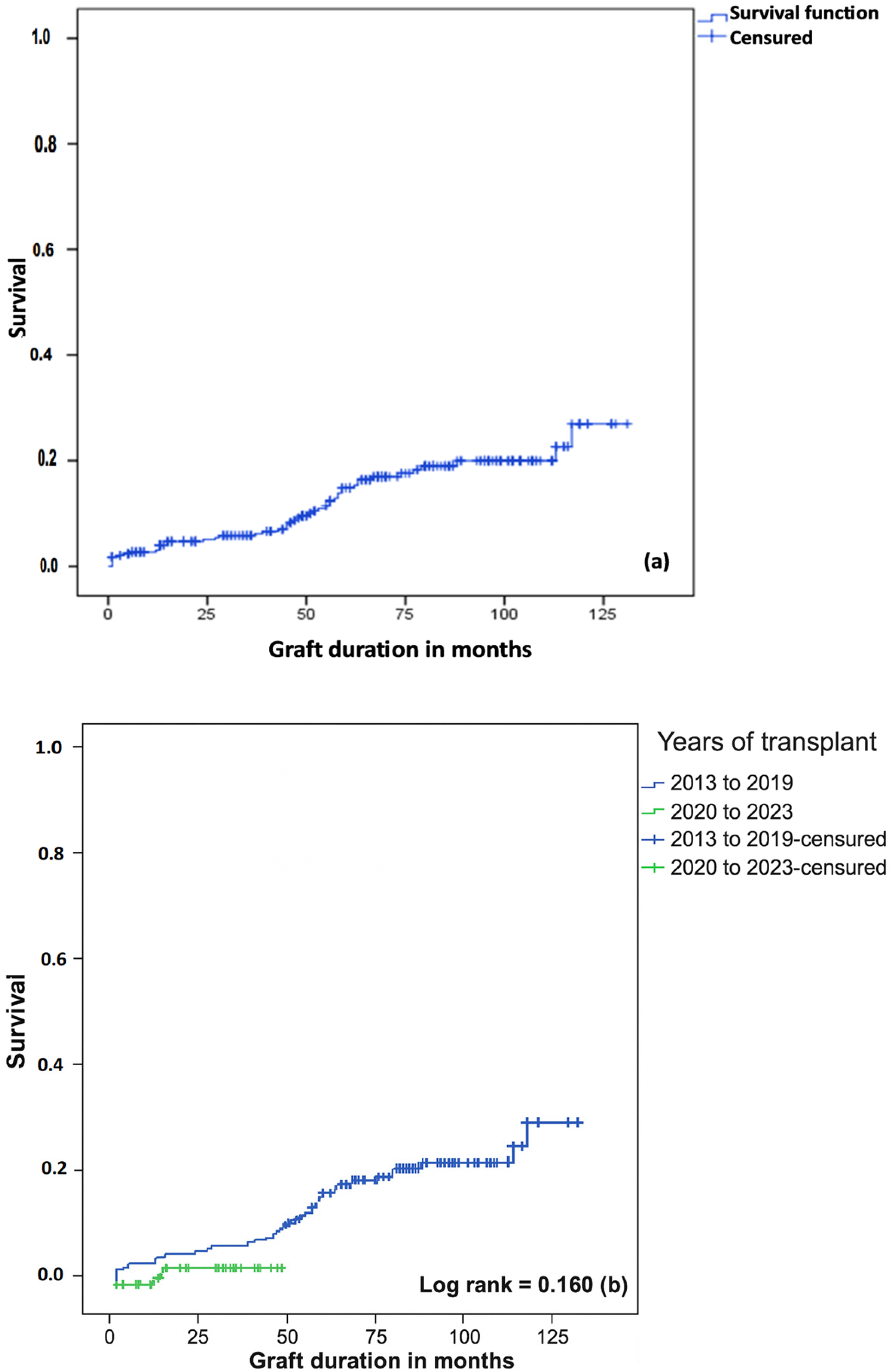

RGF remains one of the most dreaded complications following KT. Our study showed that 14.3% of KT patients developed RGF, with the majority of these cases occurring among patients transplanted before 2020. Graft survival was 97.3% at 6 months, 85.1% at 5 years, and 73.1% at 10 years. Our results are in line with the literature [

24,

25,

26]. According to a study from 1993 to 2016 [

27], of 59,162 patients who received a KT, overall graft survival was 91.4% at 1 year, 79.4% at 5 years, and 62.4% at 10 years. Graft survival is known to vary according to the timing and modalities of renal transplantation. In recent years, there has been an increasing use of donors with extended criteria and recipients with multiple comorbidities. In addition, several teams now perform ABO–incompatible transplants. For example, the ABM report estimates 3-year post-renal transplant survival at 82.4% for the period 2018 to 2022, compared with 85.3% for the period 2012 to 2014 [

11].

RGF was independently associated with intraoperative events and allograft nephropathy from 2013 to 2019.

It is known that after transplantation, the renal graft can be the site of allograft nephropathy, which is responsible for a progressive deterioration in renal function. Several studies indicate that this complication represents a major prognostic factor in long-term graft loss [

24,

28].

Most cases are attributable to causes such as calcineurin inhibitor intoxication, diabetic or hypertensive nephropathy, or viral infection, notably BK virus nephritis and cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection.

Pre-formed positive anti-HLA class I antibodies, a grade 1 IFTA score at 3 months post-transplant, and male donors were associated with RGF in the univariate analysis. It has been established that patients immunized prior to transplantation are at risk of graft dysfunction, and anti-HLA class I antibodies may appear following immunizing events, including blood transfusion (presence of platelets and granulocytes), as well as pregnancy and previous transplantation [

18]. Despite the presence of preformed anti-HLA class II Ac and positive DSA results in some patients, these factors were not associated with RGF. This variation may be explained by the fact that not all anti-HLA antibodies have the same clinical significance and do not necessarily expose patients to rejection [

25].

Furthermore, the quantification of DSA enables us to better assess its correlation with the risk of organ rejection [

26].

The association between the IFTA score and RGF corroborates data in the literature [

29]. Interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy correspond to an abnormal accumulation of connective tissue in the kidneys, resulting in structural damage and impaired kidney function [

29].

No obvious explanation exists for the role of the male donor in justifying RGF in the univariate analysis of our study.

This link was not retained in the multivariate analysis. To date, few studies have investigated the role of male donors in graft survival. However, for other grafts, notably skin, the role of the sex-linked HY system has been reported [

30]. This histocompatibility gene, located on the Y chromosome and therefore absent in women, can lead to rejection of a male skin graft transplanted to a female of the same lineage.

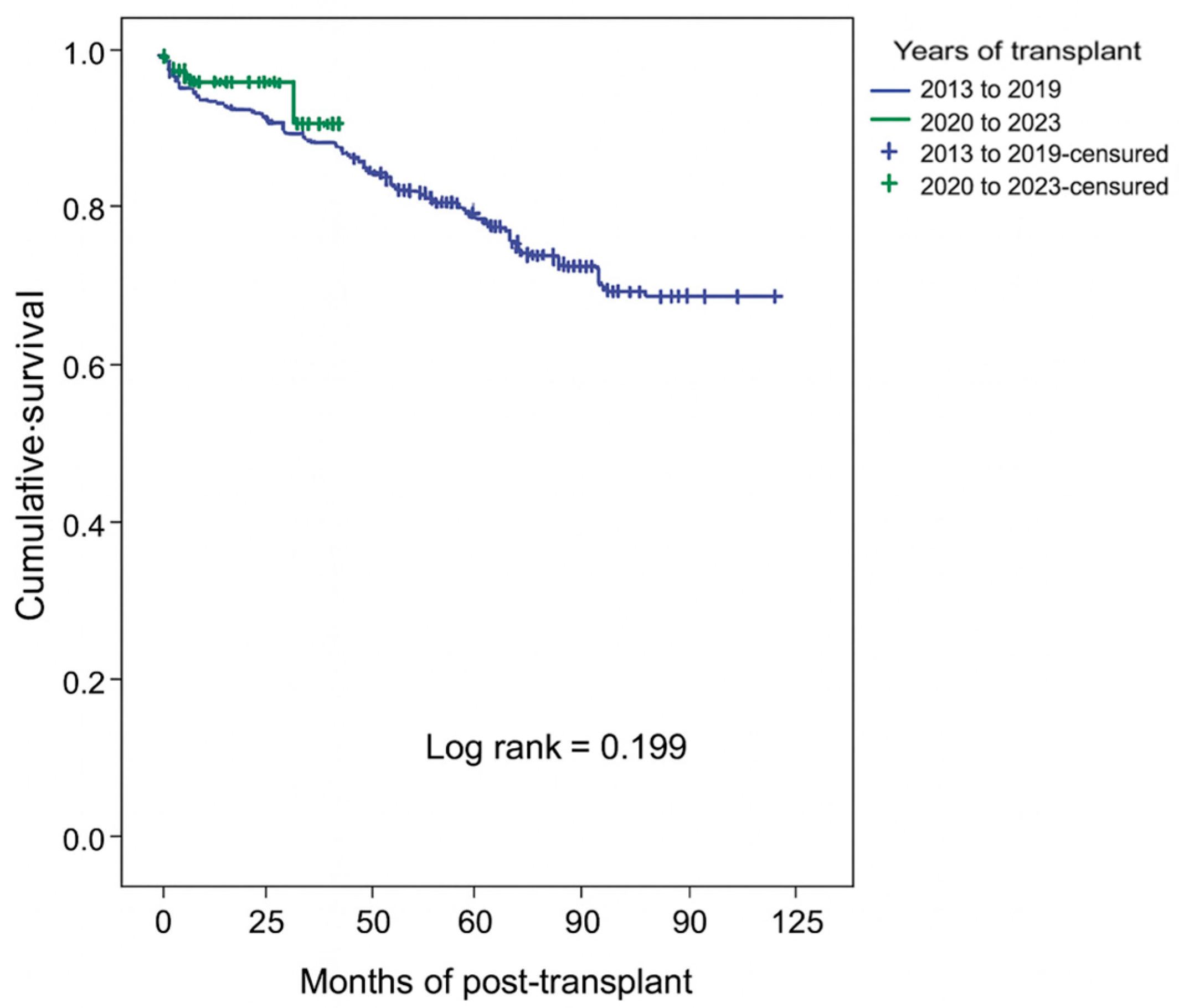

Patient survival at 6 months post-transplant was 97.3%, compared to 83.2% at 5 years and 72.3% at 10 years. Our results align with the existing literature [

11]. Patient survival was better in the absence of RGF, in younger recipients (age < 60 years), in the absence of a history of diabetes mellitus, when KT was performed in more recent years (2020–2023 vs. 2013–2019), and for a shorter CIT (≤1200 min vs. >1200 min).

These results corroborate data in the literature [

11,

31,

32]. Some patients with RGF died before being dialyzed. These are generally patients who did not present metabolic complications indicating emergency dialysis but who presented pathologies leading to death within a brief time.

Death at home, multi-visceral failure due to sepsis, and COVID-19 infection were the three main causes of patient death, regardless of the group (patients transplanted between 2013 and 2019 vs. patients transplanted between 2020 and 2023). These results are in line with the literature, which reports that infectious and cardiovascular complications are the main causes of death after KT [

31,

32].

This study has some limitations. These include the retrospective nature of the study, the duration of observation, which was limited to 4 years in the second group of patients (between the years 2020 and 2023), the monocentric nature, limiting observations to the University Hospital of Guadeloupe, the absence of certain data, such as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) quantification, and de novo DSA results. Nonetheless, our study possesses certain strengths.

It is the first to compare transplant activity before and after the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in Guadeloupe. Although there was a higher proportion of immunized patients and those with comorbidities among transplant patients in recent years, our results indicated that overall survival was unaffected.

It should also be noted that this study reported on practices carried out within the renal transplant team at the University Hospital of Guadeloupe, enabling us to consider strategies for further improving patient management.