Smartphone-Based Digital Image Processing for Fabric Drape Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Drape Coefficient Testing Procedure

2.3. Drape Coefficient Testing Methods

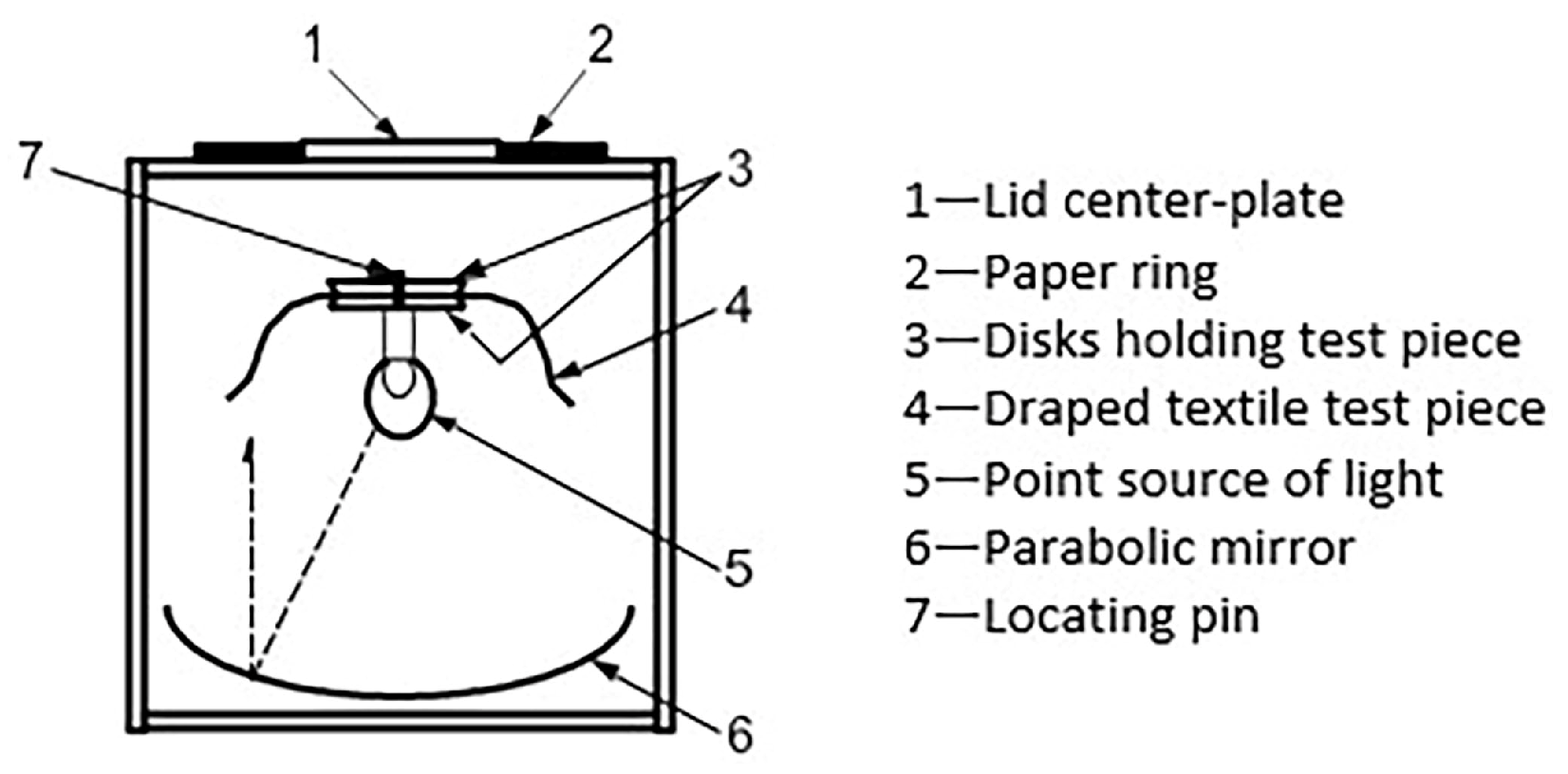

2.3.1. Conventional Cusick Method (CK)

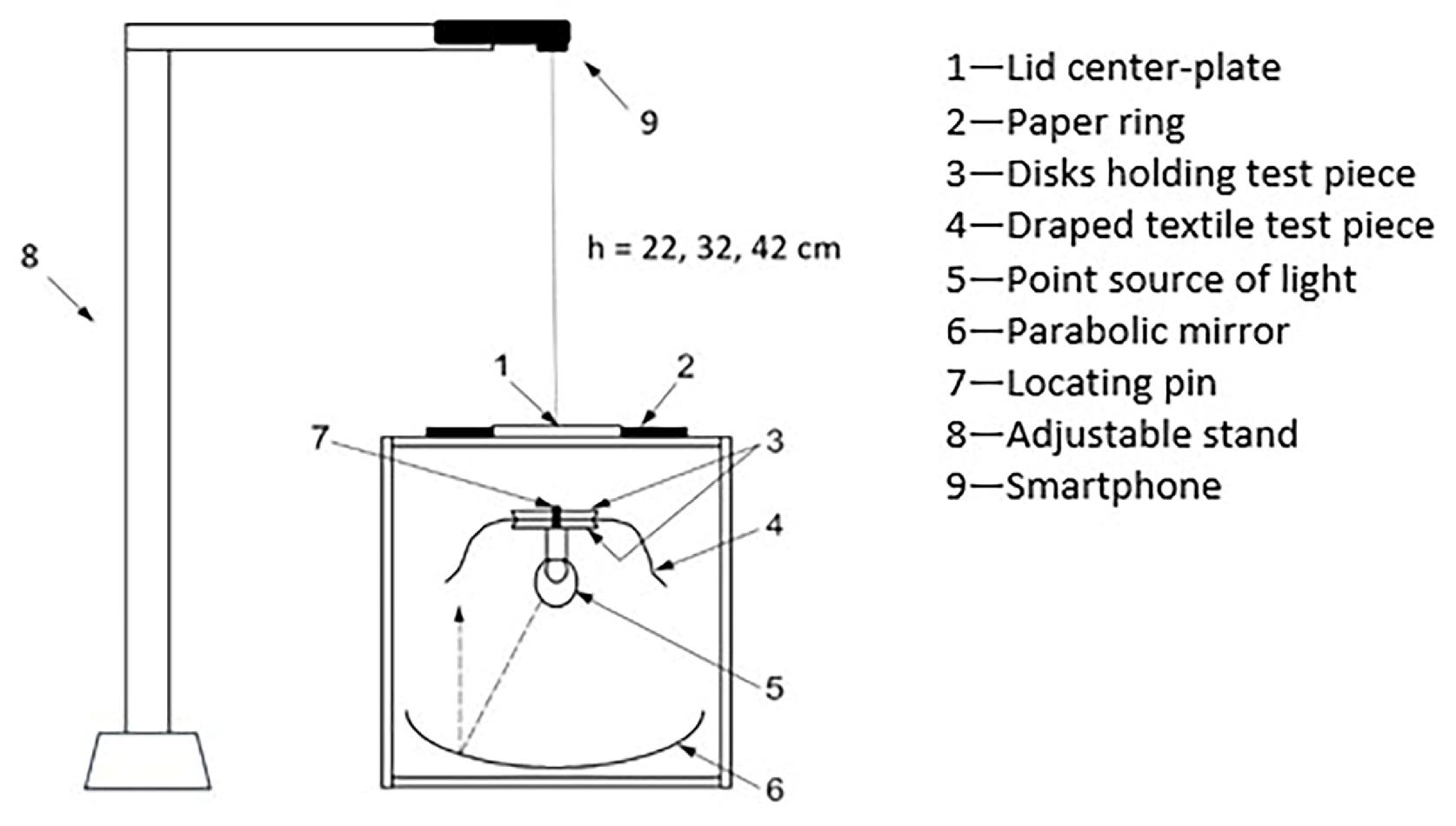

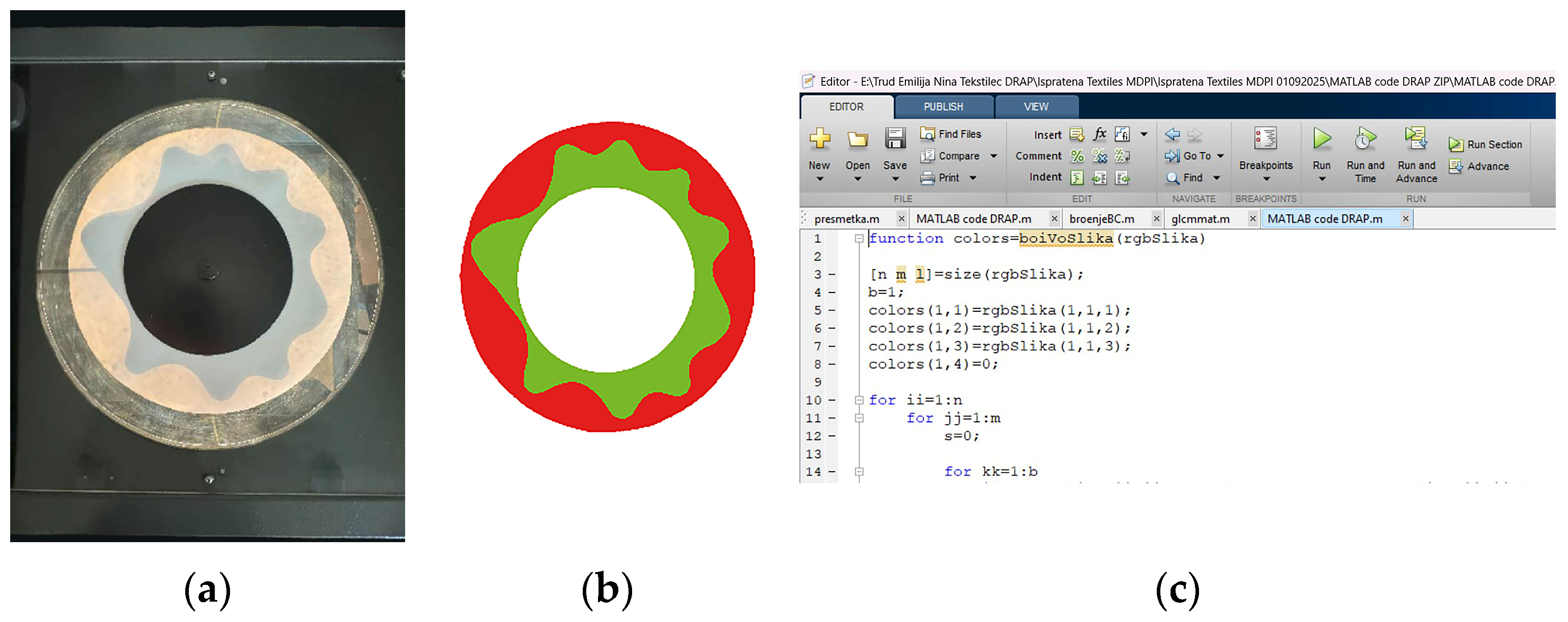

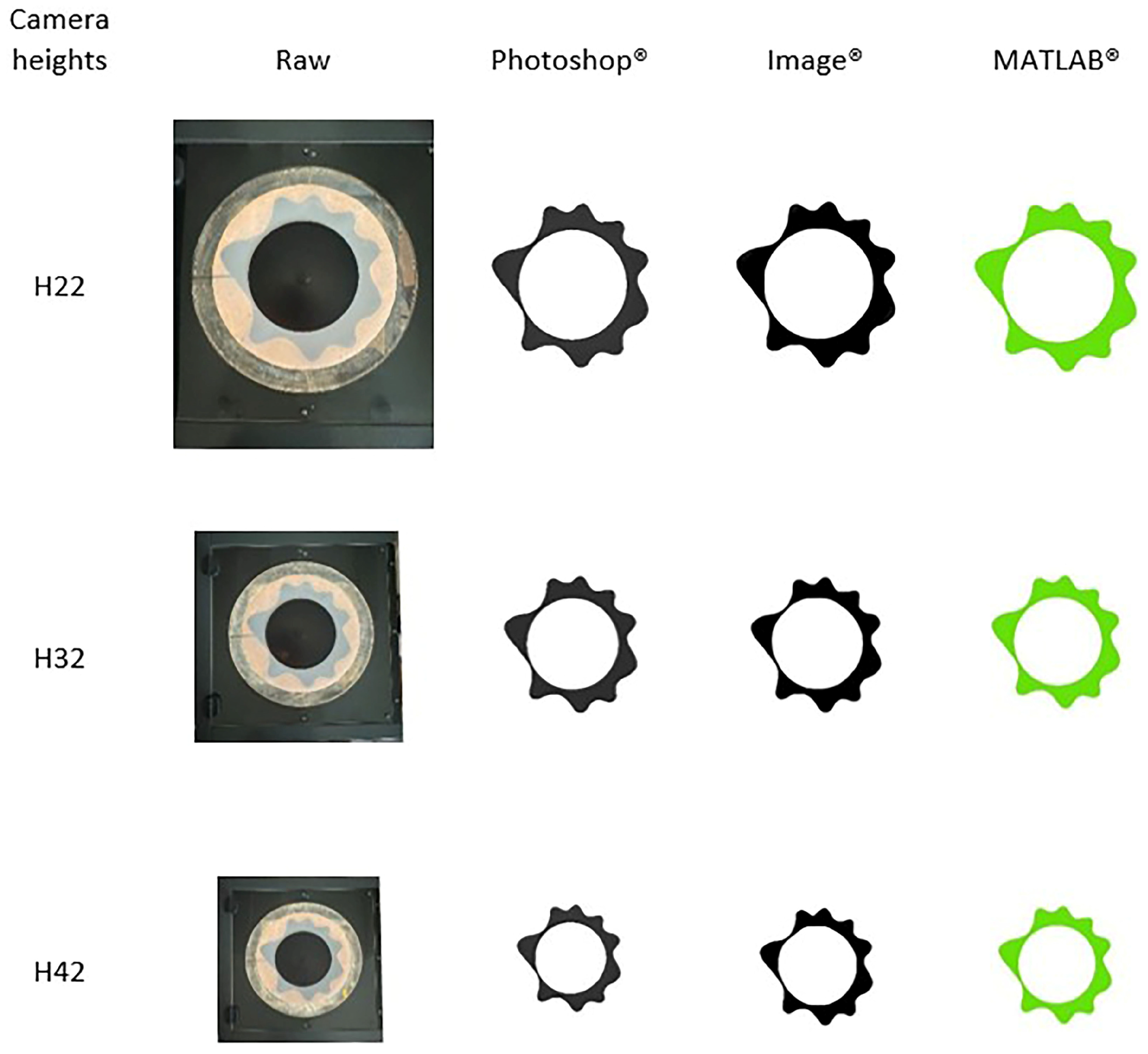

2.3.2. Smartphone-Enabled Digital Image Processing for Fabric Drape Using Photoshop® (SPDIP)

2.3.3. Smartphone-Enabled Digital Image Processing for Fabric Drape Using ImageJ® (SIDIP)

2.3.4. Smartphone-Enabled Digital Image Processing for Fabric Drape Using MATLAB® (SMDIP)

2.4. Statistical Framework for Drape Coefficient Reliability Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

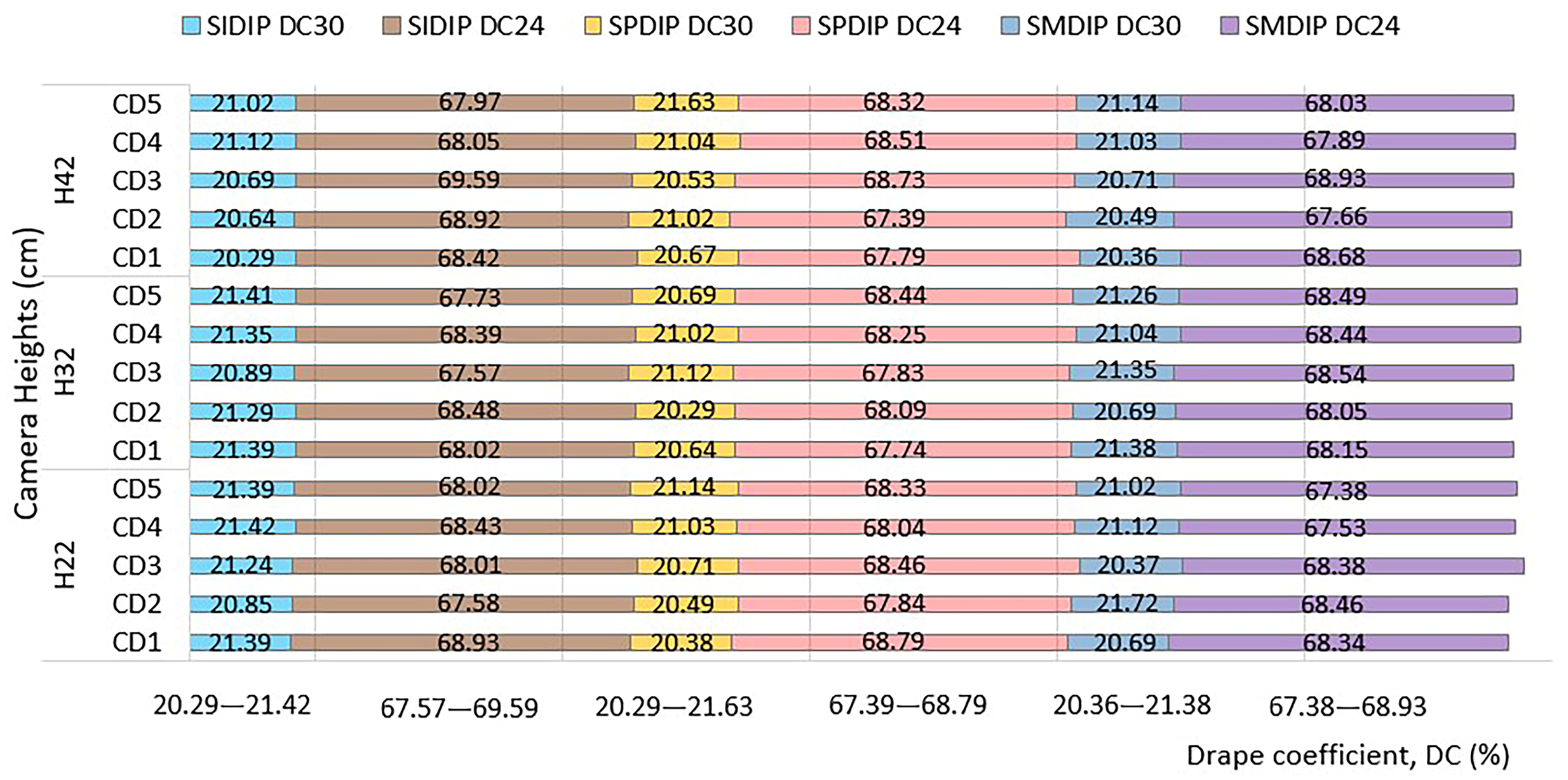

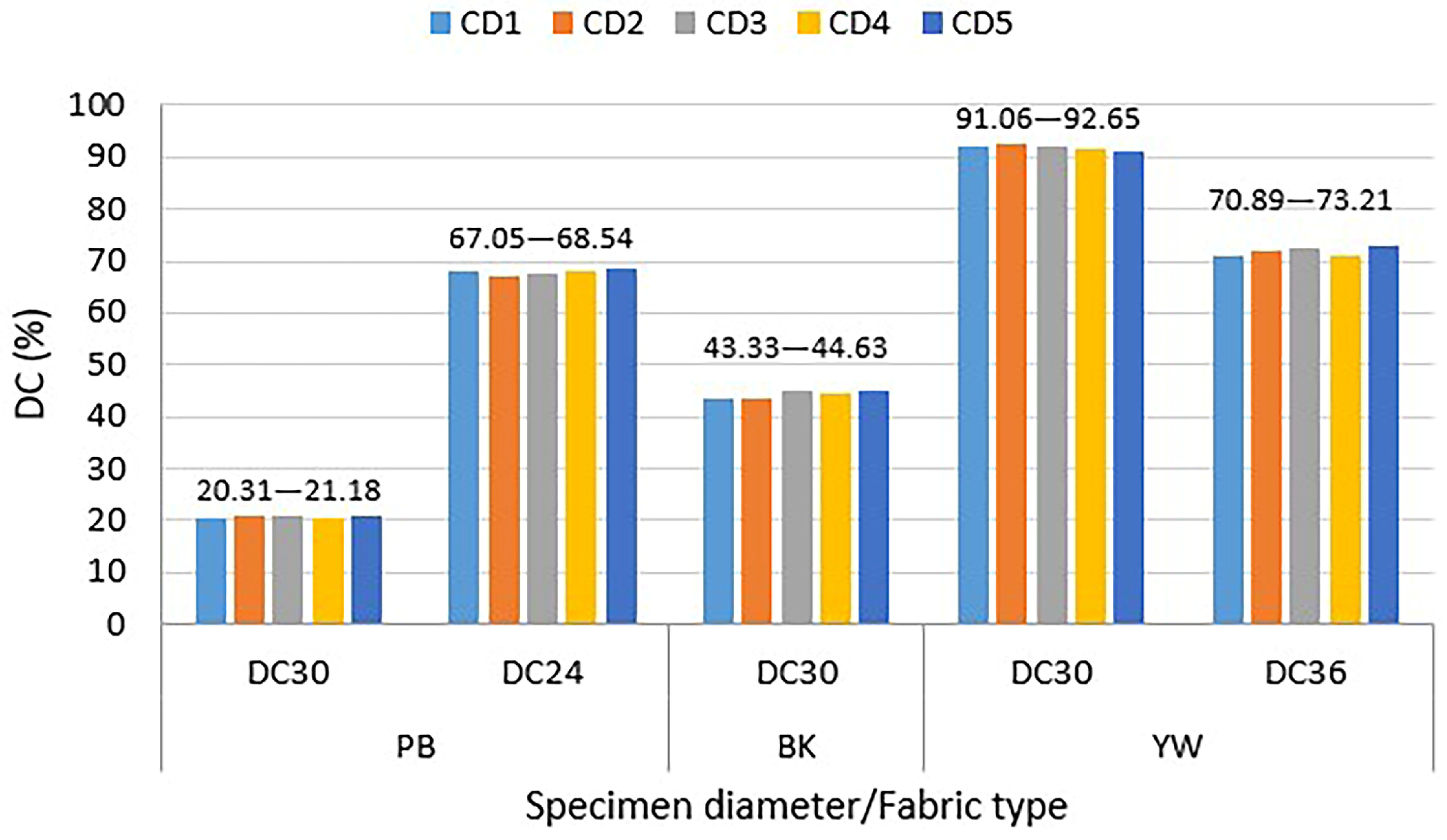

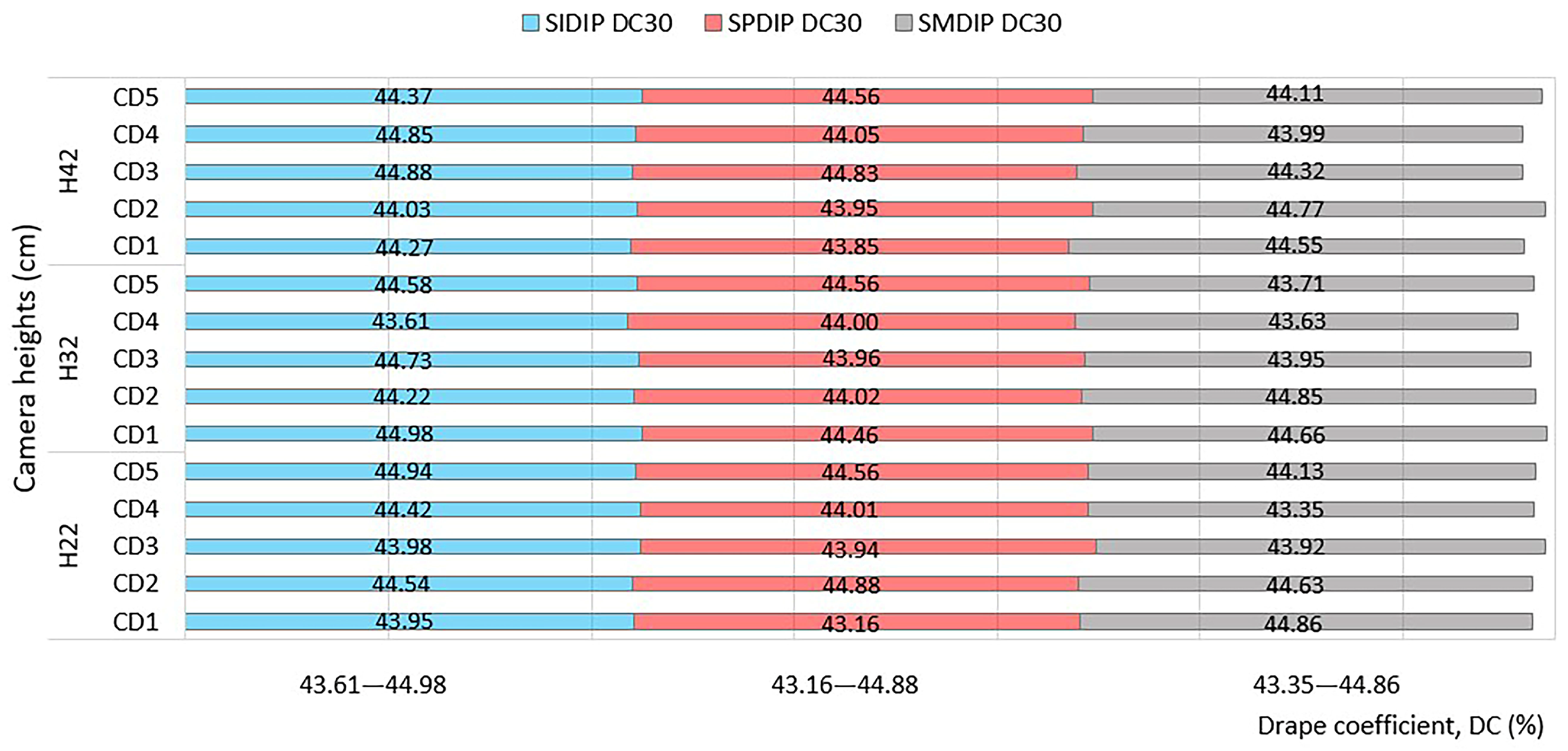

3.1. Drape Coefficient Reliability Across Fabric Weights: Influence of Camera Height and DIP Software

3.2. Reliability of Drape Coefficient Measurements Across Digital Platforms at Varying Camera Heights

3.3. Cross-Platform Reliability in Drape Coefficient Measurement Independent of Camera Height

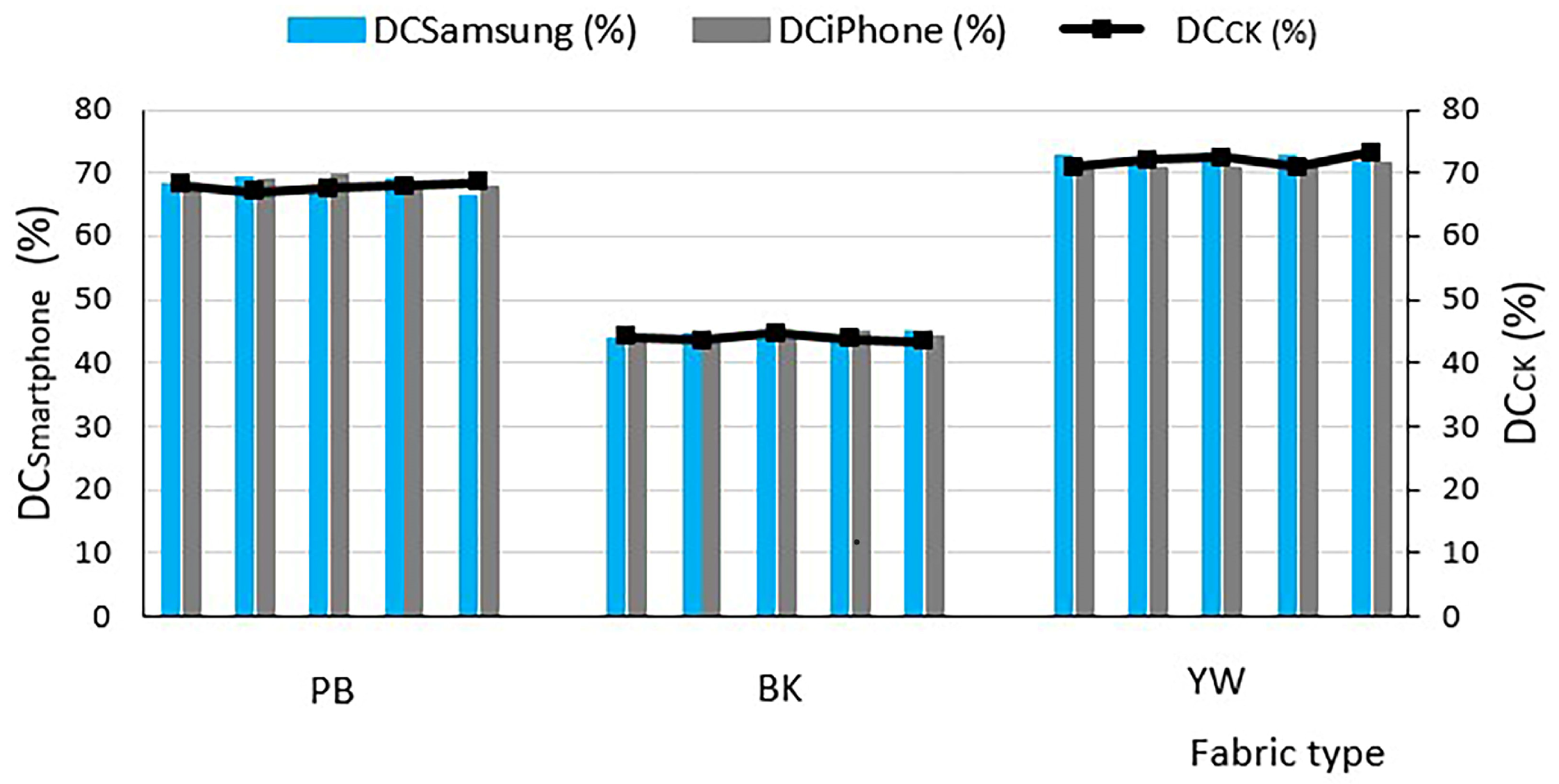

3.4. Comparison of Smartphone-Based ImageJ® Digital Image Processing Method and the Cusick Method at Optimal Camera Height

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gruhu, P.; Koske, D.; Storck, L.J.; Ehrmann, A. Three-dimensional printing by vat photopolymerization on textile fabrics: Method and mechanical properties of the textile/polymer composites. Textiles 2024, 4, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogh, C.; Broberg, H.P.; Hermansen, M.S.; Olesen, M.A.; Bak, B.V.L.B.; Lindgad, E.; Lund, E. Analysis of the performance of a new concept for automatic draping of wide reinforcement fabrics with pre-shear: A virtual prototyping study. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, R.; Acerbi, F.; Rosa, P.; Terzi, S. The role of digital technologies in the circular transition of the textile sector. J. Text. Inst. 2024, 116, 2860–2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertola, P.; Teunissen, J. Fashion 4.0: Innovating fashion industry through digital transformation. Res. J. Text. Appar. 2018, 22, 352–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoblich, M.; Al Ktash, M.; Wackenhyt, F.; Jehle, V.; Ostertag, E.; Brecht, M. Applying UV hyperspectral imaging for the quantification of honeydew content of raw cotton via PCA and PLS-R models. Textiles 2023, 3, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuno, G.; Carvalho, V.; Belsley, M.; Vasconcelos, M.R.; Soares, O.F.; Machado, J. Yarn features extraction using image processing and computer vision—A study with cotton and polyester yarns. Measurement 2015, 68, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, C. Application of image processing technology on testing blending ratio and blending irregularity of blended yarns. Text. Res. J. 2023, 86, 618–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanad, R.; Cassidy, T.; Cheung, T.L.V. Fabric and garment drape measurement—Part 1. J. Fiber Bioeng. Inform. 2012, 5, 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, R.; Cleveland, D.; Joseph, F. Characterization of Sustainable Bacterial Cellulose Fabricated with Vietnames ingredients for Potential Textile Application: Tensile and Handle Properties. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 104030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepien, M.; Frydrych, I. Analysis of the drapeability and bending rigidity of clothing packages—A preliminary study. Textiles 2025, 5, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenkare, N.; May-Plumlee, T. Evaluation of drape characteristics in fabrics. Int. J. Cloth. Sci. Technol. 2005, 17, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, L.; Fan JChau, D. Garment drape. In Clothing Appearance and Fit Science and Technology; Woodhead Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 114–134. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, B.; Yun, C. Multidimensional analysis for fabric drapability. Fash. Text. 2023, 10, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Kim, Y.J.; Shim, M.; Jun, Y.; Yun, C. Prediction and categorization of fabric drapability for 3D garment virtualization. Int. J. Cloth. Sci. Technol. 2020, 32, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Messiry, M.; El-Tarfawy, S. Investigation of fabric drape-flexural rigidity relation: Modified fabric drape coefficient. J. Text. Inst. 2020, 111, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matusiak, M. Influence of the structural parameters of woven fabrics on their drapeability. Fibres Text. East. Eur. 2017, 25, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusick, G.E. The measurement of fabric drape. J. Text. Inst. 1965, 59, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, M.; Haleem, A.; Singh, P.R.; Sinha, K.A. Digital economy to improve the culture of industry 4.0: A study on features, implementation and challenges. Green Technol. Sustain. 2024, 2, 100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, N.; Lin, C.; Xu, J. A new method for measuring fabric drape with a novel parameter for classifying fabrics. Fibers 2019, 7, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlatev, Z.; Indrie, L.; Ilieva, J.; Secan, C.; Tripa, S. Determination of used textiles drape characteristics for circular economy. Ind. Textila 2023, 74, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.R.; Link, R.E.; Kown, E.S.; Yoon, S.Y.; Sul, I.H.; Kim, S.; Park, C.K. A quantitative fabric drape evaluation system using image-processing technology, part 2: Effect of fabric properties on drape parameters. J. Test. Eval. 2010, 38, 102361. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, Y. A study of fabric-drape behaviour with image analysis Part I: Measurement, characterisation, and instability. J. Text. Inst. 1998, 89, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adbin, Y.; Taha, I. Description of Draping Behaviour of Woven Fabrics Over Single Curvatures by Image Processing and Simulation Techniques. Compos. Part B Eng. 2013, 45, 3792–3799. [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmick, M.; Basu, G. Portable digital drape meter with a unique sensor-based measurement system. Measurement 2021, 171, 108745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duong, D.P.; Luong, T.T.P.; Phan, D.N.; Thang, T.V. Correlation between material properties and actual–simulated drape of textile products. Results Eng. 2024, 22, 102077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarac, T.; Stepanović, J.; Ćirković, N. Analysis of a fabric drape profile. Text. Technol. 2018, 25, 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Indrie, L.; Ilieva, J.; Zlatev, Z.; Oana, P.I. An algorithm for the analysis of static hanging drape. Ind. Textilă. 2024, 74, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.S. Investigating parameters affecting the real and virtual drapability of silk fabrics for traditional Hanbok. Fash. Text. 2024, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Huang, L. CLO3D-Based 3D virtual fitting technology of down jacket and simulation research on dynamic effect of cloth. Wirel. Commun. Mob. Comput. 2022, 2022, 5835026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.M.; Yu, S.Y.; Ren, S.; Cheng, S.; Liu, J.Z. Close-range industrial photogrammetry and application: Review and outlook. Proc. SPIE 2020, 11568, 152–162. [Google Scholar]

- Tuan-Anh, N.; Oanh, V.T.; Hau, T.N. Experimental model of determining drape coefficient of fabric through image analyzing techniques. J. Tech. Educ. Sci. 2022, 17, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragab, A.; Fouda, A.; El-Deeb, H.; Hemdan, A.T. A simple method for measuring fabric drape using digital image processing. J. Text. Sci. Eng. 2017, 7, 1000320. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. A study on the fabric drape evaluation using a 3D scanning system based on depth camera with elevating device. J. Fash. Bus. 2015, 19, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinowska, K.; Wojnowski, W.; Tobiszewski, M. Smartphones as tools for equitable food quality assessment. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 111, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, M.M.; Julian, E.; Armengou, L.; Pividori, I.M. Evaluating smartphone-based optical readouts for immunoassays in human and veterinary healthcare: A comparative study. Talanta 2024, 275, 126106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, M.S.; Milašius, R. Factors of weave estimation and the effect of weave structure on fabric properties: A review. Fibers 2022, 10, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 3801:1977; Textiles—Woven Fabric—Determination of Mass per Unit Length and Mass per Unit Area. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1977.

- ISO 5084:1996; Textiles—Determination of Thickness of Textiles and Textile Products. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1996.

- BS EN 1049-2:1994; Textiles—Woven Fabrics—Construction—Methods of Analysis—Part 2: Determination of Number of Threads per Unit Length. BSI: London, UK, 1994.

- BS 5058:1974; Method for the Assessment of Drape of Fabrics by the Use of the Drape Meter. BSI: London, UK, 1974.

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer of Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2022; pp. 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Stylios, G.K.; Powell, N.J. Engineering the drapability of textile fabrics. Int. J. Cloth. Sci. Technol. 2003, 15, 211–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, B.J. Measurement of fabric drape and its relation to fabric mechanical properties and subjective evaluation. Cloth. Text. Res. J. 1991, 10, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, N.G. Error analysis of measurements made with KES-F system. Text. Res. J. 1989, 59, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollias, S.; Delopoulos, A. Multiresolution invariant image recognition. Expert Syst. 2002, 3, 701–740. [Google Scholar]

- Vandermeulen, W.; Puzzolante, J.L.; Scibetta, M. Understanding of tensile test results on small size specimens of certified reference material BCR-661. J. Test. Eval. 2017, 45, 20150377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, N.M.; Plastino, A.; Pinto Jonior, J.A.; Freitas, A.A. Is p-value 0.05 enough? A study on the statistical evaluation of classifiers. Knowl. Eng. Rev. 2020, 36, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, R.; Agrawal, M.; Agarwala, A. Optimizing content-preserving projections for wide-angle images. ACM Trans. Graph. 2009, 28, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pribanić, T.; Cifrek, M.; Tonković, S. Effects of image distortion and resolution on 3D reconstruction systems. In Proceedings of the First International Workshop on Image and Signal Processing and Analysis, Pula, Croatia, 14–15 June 2000; pp. 183–188. [Google Scholar]

- Minwalla, C.; Shen, E.; Thomas, P.; Hornsey, R. Correlation-based measurements of camera magnification and scale factor. IEEE Sens. J. 2009, 9, 699–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palenichka, R.M.; Zscherpel, U. Robust binary segmentation of radiographic images by using multiscale relevance function. In Proceedings of the SPIE 3691, Nonlinear Image Processing XI, San Jose, CA, USA, 3 March 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Greenland, S.; Senn, S.J.; Rothman, K.J.; Carlin, J.B.; Poole, C.; Goodman, S.N.; Altman, D.G. Statistical tests, p values, confidence intervals, and power: A guide to misinterpretations. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2016, 31, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, T.H. Composition tolerances in the manufacture of two-component textile fabrics: Part II—The control of composition variation in textile manufacture. J. Text. Inst. 1977, 68, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simfukwe, M.; Peng, B.; Li, T. Fusion of measures for image segmentation evaluation. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2019, 12, 379–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Mark | Fabric Type | Chemical Composition | Fabric Weave | Yarn Linear Density (Tex) | Mass per Unit Area (g/m2) | Fabric Thickness (mm) | Fabric Density | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warp | Weft | dwarp (cm−1) | dweft (cm−1) | ||||||

| PB | Light | 100% PES | Twill | 11 | 15 | 81.86 | 0.21 | 44 | 32 |

| BK | Medium | 60% PES/40% cotton | Twill | 16 | 24 | 113.81 | 0.20 | 55 | 33 |

| YW | Heavy | 60% PES/40% cotton | Twill | 36 | 54 | 231.74 | 0.43 | 35 | 18 |

| DS 1 | DCSIDIP (%) | DCSPDIP (%) | DCSMDIP (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H22 | H32 | H42 | H22 | H32 | H42 | H22 | H32 | H42 | |

| M (%) | 68.59 | 68.03 | 68.19 | 68.15 | 68.07 | 68.29 | 68.24 | 68.33 | 68.02 |

| SD (%) | 0.67 | 0.41 | 0.51 | 0.55 | 0.29 | 0.37 | 0.54 | 0.22 | 0.52 |

| CV (%) | 0.98 | 0.61 | 0.75 | 0.80 | 0.43 | 0.54 | 0.79 | 0.32 | 0.76 |

| AE | 1.24 | 0.76 | 0.94 | 1.01 | 0.53 | 0.68 | 0.99 | 0.40 | 0.95 |

| RE | 1.80 | 1.11 | 1.37 | 1.48 | 0.78 | 0.99 | 1.46 | 0.59 | 1.40 |

| S | 0.86 | −0.10 | 0.53 | −0.58 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.45 | −0.60 | −0.62 |

| DC (%) Different Camera Placement Heights | Analysis Output | F-Test | Analysis Output | t-Test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPDIP | SIDIP | SMDIP | SPDIP | SIDIP | SMDIP | |||

| DCH22 vs. DCH32 | M1 | 68.148 | 68.590 | 68.238 | M1 | 68.148 | 68.590 | 68.238 |

| M2 | 68.070 | 68.028 | 68.334 | M2 | 68.070 | 68.028 | 68.334 | |

| V1 | 0.301 | 0.453 | 0.293 | V1 | 0.301 | 0.453 | 0.293 | |

| V2 | 0.084 | 0.171 | 0.048 | V2 | 0.0841 | 0.171 | 0.048 | |

| df | 4 | 4 | 4 | df | 8 | 8 | 8 | |

| FS | 3.575 | 2.658 | 6.091 | tS | 0.281 | 1.591 | −0.367 | |

| p | 0.122 | 0.183 | 0.055 | p | 0.786 | 0.150 | 0.723 | |

| FC | 6.388 | 6.388 | 6.388 | tC | 2.306 | 2.306 | 2.306 | |

| DCH22 vs. DCH42 | M1 | 68.148 | 68.590 | 68.238 | M1 | 68.148 | 68.590 | 68.238 |

| M2 | 68.292 | 68.194 | 68.018 | M2 | 68.292 | 68.194 | 68.018 | |

| V1 | 0.301 | 0.453 | 0.293 | V1 | 0.301 | 0.453 | 0.293 | |

| V2 | 0.136 | 0.260 | 0.269 | V2 | 0.136 | 0.260 | 0.269 | |

| df | 4 | 4 | 4 | df | 8 | 8 | 8 | |

| FS | 2.204 | 1.747 | 1.091 | tS | −0.487 | 1.049 | 0.656 | |

| p | 0.231 | 0.301 | 0.468 | p | 0.639 | 0.325 | 0.530 | |

| FC | 6.388 | 6.388 | 6.388 | tC | 2.306 | 2.306 | 2.306 | |

| DCH32 vs. DCH42 | M1 | 68.070 | 68.028 | 68.334 | M1 | 68.070 | 68.028 | 68.334 |

| M2 | 68.292 | 68.194 | 68.018 | M2 | 68.292 | 68.194 | 68.018 | |

| V1 | 0.084 | 0.171 | 0.048 | V1 | 0.084 | 0.171 | 0.048 | |

| V2 | 0.136 | 0.260 | 0.269 | V2 | 0.136 | 0.260 | 0.269 | |

| df | 4 | 4 | 4 | df | 8 | 8 | 8 | |

| FS | 0.616 | 0.657 | 0.179 | tS | −1.057 | −0.566 | 1.255 | |

| p | 0.325 | 0.347 | 0.062 | p | 0.321 | 0.587 | 0.245 | |

| FC | 6.388 | 6.388 | 6.388 | tC | 2.306 | 2.306 | 2.306 | |

| DC (%) Different Camera Placement Heights | Analysis Output | F-Test | Analysis Output | t-Test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPDIP | SIDIP | SMDIP | SPDIP | SIDIP | SMDIP | |||

| DCH22 vs. DCH32 | M1 | 44.248 | 44.200 | 44.348 | M1 | 44.248 | 44.200 | 44.348 |

| M2 | 44.200 | 44.110 | 44.160 | M2 | 44.200 | 44.110 | 44.160 | |

| V1 | 0.181 | 0.082 | 0.101 | V1 | 0.1806 | 0.082 | 0.101 | |

| V2 | 0.082 | 0.434 | 0.313 | V2 | 0.082 | 0.434 | 0.313 | |

| df | 4 | 4 | 4 | df | 8 | 8 | 8 | |

| FS | 2.208 | 0.188 | 0.323 | tS | 0.210 | 0.280 | 0.653 | |

| p | 0.231 | 0.067 | 0.149 | p | 0.839 | 0.786 | 0.532 | |

| FC | 6.388 | 6.388 | 6.388 | tC | 2.306 | 2.306 | 2.306 | |

| DCH22 vs. DCH42 | M1 | 44.248 | 44.480 | 44.348 | M1 | 44.248 | 44.480 | 44.348 |

| M2 | 44.110 | 44.424 | 43.978 | M2 | 44.110 | 44.366 | 43.978 | |

| V1 | 0.181 | 0.139 | 0.101 | V1 | 0.181 | 0.139 | 0.101 | |

| V2 | 0.434 | 0.283 | 0.330 | V2 | 0.434 | 0.171 | 0.330 | |

| df | 4 | 4 | 4 | df | 8 | 8 | 8 | |

| FS | 0.416 | 0.491 | 0.306 | tS | 0.394 | 0.458 | 1.260 | |

| p | 0.208 | 0.254 | 0.139 | p | 0.704 | 0.659 | 0.243 | |

| FC | 6.388 | 6.388 | 6.388 | tC | 2.306 | 2.306 | 2.306 | |

| DCH32 vs. DCH42 | M1 | 44.200 | 44.424 | 44.160 | M1 | 44.200 | 44.424 | 44.160 |

| M2 | 44.110 | 44.366 | 43.978 | M2 | 44.110 | 44.366 | 43.978 | |

| V1 | 0.082 | 0.283 | 0.313 | V1 | 0.082 | 0.283 | 0.313 | |

| V2 | 0.434 | 0.171 | 0.330 | V2 | 0.434 | 0.171 | 0.330 | |

| df | 4 | 4 | 4 | df | 8 | 8 | 8 | |

| FS | 0.188 | 1.652 | 0.950 | tS | 0.280 | 0.192 | 0.507 | |

| p | 0.067 | 0.319 | 0.480 | p | 0.786 | 0.852 | 0.626 | |

| FC | 6.388 | 6.388 | 6.388 | tC | 2.306 | 2.306 | 2.306 | |

| DC (%) Different Camera Placement Heights | Analysis Output | F-Test | Analysis Output | t-Test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPDIP | SIDIP | SMDIP | SPDIP | SIDIP | SMDIP | |||

| DCH22 vs. DCH32 | M1 | 71.338 | 71.130 | 71.350 | M1 | 71.338 | 71.130 | 71.350 |

| M2 | 71.780 | 71.578 | 71.796 | M2 | 71.78 | 71.578 | 71.796 | |

| V1 | 0.209 | 0.200 | 0.367 | V1 | 0.209 | 0.200 | 0.367 | |

| V2 | 0.186 | 0.578 | 0.444 | V2 | 0.186 | 0.578 | 0.444 | |

| df | 4 | 4 | 4 | df | 8 | 8 | 8 | |

| FS | 1.127 | 0.346 | 0.827 | tS | −1.572 | −1.135 | −1.108 | |

| p | 0.455 | 0.164 | 0.429 | p | 0.155 | 0.289 | 0.300 | |

| FC | 6.388 | 6.388 | 6.388 | tC | 2.306 | 2.306 | 2.306 | |

| DCH22 vs. DCH42 | M1 | 71.338 | 71.130 | 71.350 | M1 | 71.338 | 71.130 | 71.350 |

| M2 | 71.766 | 71.234 | 71.456 | M2 | 71.766 | 71.234 | 71.456 | |

| V1 | 0.209 | 0.200 | 0.367 | V1 | 0.209 | 0.200 | 0.367 | |

| V2 | 0.570 | 0.152 | 0.473 | V2 | 0.570 | 0.152 | 0.473 | |

| df | 4 | 4 | 4 | df | 8 | 8 | 8 | |

| FS | 0.367 | 1.319 | 0.776 | tS | −1.084 | −0.392 | −0.259 | |

| p | 0.178 | 0.397 | 0.406 | p | 0.310 | 0.705 | 0.802 | |

| FC | 6.388 | 6.388 | 6.388 | tC | 2.306 | 2.303 | 2.306 | |

| DCH32 vs. DCH42 | M1 | 71.780 | 71.578 | 71.796 | M1 | 71.780 | 71.578 | 71.796 |

| M2 | 71.766 | 71.234 | 71.456 | M2 | 71.766 | 71.234 | 71.456 | |

| V1 | 0.186 | 0.578 | 0.444 | V1 | 0.186 | 0.578 | 0.444 | |

| V2 | 0.578 | 0.152 | 0.473 | V2 | 0.570 | 0.152 | 0.473 | |

| df | 4 | 4 | 4 | df | 8 | 8 | 8 | |

| FS | 0.326 | 3.809 | 0.938 | tS | 0.036 | 0.900 | 0.794 | |

| p | 0.152 | 0.112 | 0.476 | p | 0.972 | 0.394 | 0.450 | |

| FC | 6.388 | 6.388 | 6.388 | tC | 2.306 | 2.306 | 2.306 | |

| Fabric Type | Analysis Output | F-Test | Analysis Output | t-Test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCSPDIP vs. DCSIDIP 1 | DCSPDIP vs. DCSMDIP 1 | DCSIDIP vs. DCSMDIP 1 | DCSPDIP vs. DCSIDIP 1 | DCSPDIP vs. DCSMDIP 1 | DCSIDIP vs. DCSMDIP 1 | |||

| PB | M1 | 68.170 | 68.170 | 68.271 | M1 | 68.17 | 68.170 | 68.271 |

| M2 | 68.271 | 68.197 | 68.197 | M2 | 68.271 | 68.197 | 68.197 | |

| V1 | 0.158 | 0.158 | 0.312 | V1 | 0.158 | 0.158 | 0.312 | |

| V2 | 0.312 | 0.193 | 0.193 | V2 | 0.312 | 0.193 | 0.193 | |

| df | 14 | 14 | 14 | df | 28 | 28 | 28 | |

| FS | 0.506 | 0.818 | 1.616 | tS | −0.569 | −0.174 | 0.403 | |

| p | 0.107 | 0.356 | 0.190 | p | 0.574 | 0.863 | 0.690 | |

| FC | 2.484 | 2.484 | 2.484 | tC | 2.048 | 2.048 | 2.048 | |

| BK | M1 | 44.186 | 44.186 | 44.423 | M1 | 44.186 | 44.186 | 44.423 |

| M2 | 44.423 | 44.162 | 44.162 | M2 | 44.423 | 44.162 | 44.162 | |

| V1 | 0.203 | 0.202 | 0.172 | V1 | 0.203 | 0.203 | 0.172 | |

| V2 | 0.172 | 0.237 | 0.237 | V2 | 0.172 | 0.237 | 0.237 | |

| df | 14 | 14 | 14 | df | 28 | 28 | 28 | |

| FS | 1.179 | 0.854 | 0.724 | tS | −1.503 | 0.140 | 1.583 | |

| p | 0.381 | 0.386 | 0.277 | p | 0.144 | 0.890 | 0.125 | |

| FC | 2.484 | 2.484 | 2.484 | tC | 2.048 | 2.048 | 2.048 | |

| YW | M1 | 71.628 | 71.628 | 71.314 | M1 | 71.628 | 71.628 | 71.31 |

| M2 | 71.314 | 71.534 | 71.534 | M2 | 71.314 | 71.534 | 71.53 | |

| V1 | 0.321 | 0.321 | 0.305 | V1 | 0.321 | 0.321 | 0.305 | |

| V2 | 0.305 | 0.406 | 0.406 | V2 | 0.305 | 0.406 | 0.406 | |

| df | 14 | 14 | 14 | df | 28 | 28 | 28 | |

| FS | 1.052 | 0.791 | 0.753 | tS | 1.537 | 0.427 | −1.011 | |

| p | 0.463 | 0.334 | 0.301 | p | 0.136 | 0.673 | 0.321 | |

| FC | 2.484 | 2.484 | 2.484 | tC | 2.048 | 2.048 | 2.048 | |

| DS 1 | DCCK | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PB | BK | YW | |

| M (%) | 67.85 | 43.88 | 71.93 |

| SD (%) | 0.55 | 0.50 | 0.98 |

| CV (%) | 0.81 | 1.14 | 1.36 |

| AE (%) | 1.01 | 0.92 | 1.80 |

| RE (%) | 1.49 | 2.09 | 2.50 |

| S | −0.43 | 0.83 | 1.19 |

| DS 1 | DCSIDIP (%) | DCSPDIP (%) | DCSMDIP (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H22 | H32 | H42 | H22 | H32 | H42 | H22 | H32 | H42 | |

| M (%) | 44.48 | 44.42 | 44.37 | 44.25 | 44.20 | 44.11 | 44.35 | 44.16 | 43.98 |

| SD (%) | 0.37 | 0.53 | 0.41 | 0.42 | 0.29 | 0.66 | 0.32 | 0.56 | 0.57 |

| CV (%) | 0.84 | 1.20 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 0.65 | 1.49 | 0.72 | 1.27 | 1.31 |

| AE | 0.68 | 0.98 | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.53 | 1.21 | 0.58 | 1.03 | 1.05 |

| RE | 1.54 | 2.20 | 1.71 | 1.76 | 1.19 | 2.74 | 1.32 | 2.33 | 2.40 |

| S | 0.10 | −0.95 | 0.38 | 0.70 | 0.65 | −0.45 | 0.31 | 0.48 | 0.87 |

| DS 1 | DCSIDIP (%) | DCSPDIP (%) | DCSMDIP (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H22 | H32 | H42 | H22 | H32 | H42 | H22 | H32 | H42 | |

| M (%) | 71.13 | 71.58 | 71.23 | 71.34 | 71.78 | 71.77 | 71.35 | 71.80 | 71.46 |

| SD (%) | 0.45 | 0.76 | 0.39 | 0.46 | 0.43 | 0.76 | 0.61 | 0.67 | 0.69 |

| CV (%) | 0.63 | 1.06 | 0.55 | 0.64 | 0.60 | 1.05 | 0.85 | 0.93 | 0.96 |

| AE | 0.82 | 1.40 | 0.72 | 0.84 | 0.79 | 1.39 | 1.11 | 1.22 | 1.26 |

| RE | 1.16 | 1.95 | 1.00 | 1.18 | 1.10 | 1.93 | 1.56 | 1.70 | 1.77 |

| S | 0.62 | −0.25 | 0.83 | −0.37 | 0.83 | 0.22 | −0.44 | −0.51 | −0.79 |

| Sample Designation | Analysis Output | (PB) DCCK24 vs. DCSIDIP24 1 | (BK) DCCK30 vs. DCSIDIP30 1 | (YW) DCCK36 vs. DCSIDIP36 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-test | M1 | 67.848 | 43.876 | 71.930 |

| M2 | 68.590 | 44.480 | 71.330 | |

| V1 | 0.305 | 0.248 | 0.957 | |

| V2 | 0.453 | 0.139 | 0.180 | |

| df | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Fs | 0.672 | 1.788 | 5.314 | |

| p | 0.355 | 0.294 | 0.067 | |

| FC | 6.388 | 6.388 | 6.388 | |

| t-test | M1 | 67.848 | 43.876 | 71.930 |

| M2 | 68.590 | 44.480 | 71.330 | |

| V1 | 0.305 | 0.248 | 0.958 | |

| V2 | 0.453 | 0.139 | 0.180 | |

| df | 8 | 8 | 8 | |

| ts | −1.905 | −2.170 | 1.257 | |

| p | 0.093 | 0.062 | 0.244 | |

| tC | 2.306 | 2.306 | 2.306 |

| Sample Designation | Analysis Output | (PB) DCCK24 vs. DCSIDIP24 1 | (BK) DCCK30 vs. DCSIDIP30 1 | (YW) DCCK36 vs. DCSIDIP36 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F-test | M1 | 67.848 | 43.876 | 71.93 |

| M2 | 68.086 | 44.216 | 72.47 | |

| V1 | 0.304 | 0.248 | 0.958 | |

| V2 | 1.417 | 0.125 | 0.275 | |

| df | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Fs | 0.215 | 1.979 | 3.477 | |

| p | 0.082 | 0.262 | 0.127 | |

| FC | 6.388 | 6.388 | 6.388 | |

| t-test | M1 | 67.848 | 43.876 | 71.93 |

| M2 | 68.086 | 44.216 | 72.47 | |

| V1 | 0.304 | 0.248 | 0.958 | |

| V2 | 1.417 | 0.125 | 0.275 | |

| df | 8 | 8 | 8 | |

| ts | −0.405 | −1.243 | −1.086 | |

| p | 0.695 | 0.248 | 0.308 | |

| tC | 2.306 | 2.306 | 2.306 |

| Fabric Type | Mean DCCK (%) | Mean DCiPhone (%) | Mean DCSamsung (%) | k (iPhone/Cusick) | k (Samsung/Cusick) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PB | 67.85 | 68.59 | 68.09 | 1.011 | 1.004 |

| BK | 43.88 | 44.48 | 44.32 | 1.014 | 1.010 |

| YW | 71.93 | 71.13 | 72.43 | 0.989 | 1.007 |

| Device | Intercept (a) | Slope (b = Coefficient of Compliance) | R2 | p-Value | 95% Confidence Interval (b) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iPhone | 2.03 | 0.97 | 0.993 | 1.57 × 10−15 | 0.923–1.019 |

| Samsung | 0.75 | 0.99 | 0.991 | 1.48 × 10−14 | 0.936–1.052 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Toshikj, E.; Mladenovikj, N. Smartphone-Based Digital Image Processing for Fabric Drape Assessment. Textiles 2025, 5, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/textiles5040063

Toshikj E, Mladenovikj N. Smartphone-Based Digital Image Processing for Fabric Drape Assessment. Textiles. 2025; 5(4):63. https://doi.org/10.3390/textiles5040063

Chicago/Turabian StyleToshikj, Emilija, and Nina Mladenovikj. 2025. "Smartphone-Based Digital Image Processing for Fabric Drape Assessment" Textiles 5, no. 4: 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/textiles5040063

APA StyleToshikj, E., & Mladenovikj, N. (2025). Smartphone-Based Digital Image Processing for Fabric Drape Assessment. Textiles, 5(4), 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/textiles5040063