1. Introduction

Aviation has emerged as a central topic of inquiry in tourism and climate change research, owing to its disproportionate contribution to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions relative to other subsectors (

Debbage & Debbage, 2019;

Sun et al., 2024). Tourism is estimated to generate approximately 8% of global GHG emissions, with aviation alone responsible for 52% of direct sectoral emissions, equivalent to 20% of tourism’s total emissions (

Debbage & Debbage, 2019;

Sun et al., 2024). This is disproportionality mirrored in travel consumption patterns, where fewer than 12% of the global population undertakes a flight in any given year, yet the top 1% of fliers account for more than half of all commercial aviation CO

2 emissions (

Gössling & Humpe, 2020). The resulting concentration of emissions among a small cohort has framed passenger aviation as a uniquely top-heavy source of environmental externalities, prompting calls for demand-side interventions aimed at curbing frequent flying.

The tension between aviation’s economic significance for tourism-dependent destinations and the imperative to reduce emissions captures the competing priorities faced by policymakers, industry stakeholders, and travelers. This conflict is further compounded by the persistence of entrenched mobility preferences, cultural norms surrounding leisure travel, and the structural reliance of global tourism on long-haul connectivity. At a behavioral level, this dilemma resonates with the broader value–action gap in sustainable tourism, i.e., travelers frequently convey environmental concern yet continue engaging in carbon-intensive travel behaviors (

Chaplin & Wyton, 2014;

Juvan & Dolnicar, 2014).

Although the value–action gap has been widely documented, less attention has been directed toward the concept of flight behavioral integrity. Flight behavioral integrity, within the context of the current study, is defined as the degree of alignment (or misalignment) between professed intention to reduce flying for environmental reasons and actual flight behavior. Integrating this concept into tourism research provides a nuanced lens through which to examine climate-policy support. Specifically, the extent to which integrity profiles (e.g., travelers who espouse environmental concern yet continue to fly) remain supportive of mitigation measures offers an important avenue for both theory and practice. For behavior-change models, behavioral integrity represents a distinct predictor of climate-policy attitudes beyond either values or behaviors alone. For policy design, it introduces segmentation opportunities whereby interventions may engage value-driven but behaviorally inconsistent travelers as allies in advancing decarbonization, thereby linking individual psychological dynamics with system-level strategies for reducing aviation emissions.

1.1. Travelers’ Environmental Behavioral Integrity of Flying

Environmental psychology has long documented a disjunction between individuals’ professed environmental concern and their actual travel behavior. Even self-identified environmentalists, who articulate strong concern about climate change, frequently continue to engage in carbon-intensive travel such as long-haul aviation. This inconsistency is often rationalized through appeals to structural constraints (e.g., limited alternatives), subjective needs (e.g., rest, leisure), or compensatory mechanisms (e.g., reliance on carbon offsets) (

Chaplin & Wyton, 2014;

Higham et al., 2014;

Juvan & Dolnicar, 2014). For instance, long-haul leisure trips to island destinations (e.g., the Balearics/Canaries) make non-air options impractical for the majority of tourists, illustrating the structural constraints these theories describe.

Although this body of work has been influential in demonstrating that attitudes alone are insufficient predictors of sustainable consumption, scholarship on the value–action gap has remained largely descriptive. Much of it has focused on antecedents that exacerbate misalignment, such as divergent motivational drivers for environmental attitudes versus behaviors (

Barr, 2006;

Blake, 1999;

Kollmuss & Agyeman, 2002), while paying comparatively less attention to whether value–behavior congruence itself carries implications for downstream policy attitudes. Tourism studies seldom trace these psychological dynamics into concrete traveler or industry decisions (e.g., support for destination fees, airport expansions, or rail–air integration). Bridging this gap is essential for designing sector-specific interventions as insights from related domains of behavioral integrity research suggest that alignment (or misalignment) between values and actions may shape the strength and stability of individuals’ support for systemic climate solutions.

Behavioral integrity, conceptually similar to the value–action gap, denotes the degree of congruence between individuals’ espoused values and their enacted behaviors (

Simons, 2002;

Simons et al., 2022;

Tomlinson et al., 2014). However, whereas the value–action gap has typically been operationalized as a descriptive discrepancy, behavioral integrity foregrounds the psychological and behavioral consequences of alignment versus misalignment. Misalignment, in particular, is theorized to activate regulatory mechanisms such as cognitive dissonance, moral licensing, and moral compensation (

Blanken et al., 2015;

Brañas-Garza et al., 2013;

Mathex et al., 2025). For example, in laboratory economic games, participants whose behavior conflicted with their moral self-concept regulated themselves through such alternating cycles to restore self-image (

Brañas-Garza et al., 2013). In organizational contexts, leaders with low behavioral integrity were more likely to self-license by rationalizing harmful behavior (

Effron & Conway, 2015;

Klotz & Bolino, 2013). Similarly, individuals who committed private moral violations often engaged in compensatory prosocial acts (

Mathex et al., 2025).

Comparable patterns are also evident within the environmental domain, where individuals confronted with dissonance between their pro-environmental values and carbon-intensive behaviors adopt a variety of regulatory strategies to mitigate psychological tension (

Bentler et al., 2023). Some invoke prior pro-environmental actions as a form of moral credit (

Song et al., 2024), thereby legitimizing the continuation of high-impact practices such as flying while simultaneously reducing discomfort and dampening motivation for behavioral change (

Burger et al., 2022). Others engage in compensatory acts that are peripheral to the core behavior, such as hotel towel reuse or the purchase of carbon offsets, which help restore moral self-concept without confronting the main inconsistency of frequent flying (

Mathex et al., 2025;

Wang et al., 2025). In parallel, many travelers minimize or reframe the climate impact of air travel by emphasizing its economic importance for destinations or by comparing it favorably to other emission sources, thereby easing dissonance while maintaining established travel habits (

Juvan & Dolnicar, 2014;

Pratt & Tolkach, 2023;

Schrems & Upham, 2020).

Behavioral integrity thus provides a conceptual bridge between individual psychology and collective political outcomes by shaping both personal credibility and coalition-building potential in social and political arenas (

Tomlinson et al., 2014). This credibility may influence public acceptance of measures that affect visitors directly (e.g., short-haul bans, tourism levies), making integrity profiles practically relevant for policy rollouts. Despite this theoretical importance, empirical inquiry into whether distinct integrity profiles, such as high-emission individuals with strong pro-environmental values, translate into systematic differences in climate-policy support remains limited. Advancing this line of research is critical for designing interventions that do not merely rely on behavioral conformity but instead leverage varied integrity profiles to build broader bases of support for environmental initiatives.

1.2. Climate Attitudes, Emotions, and Behavioral Correlates of Environmentalism

A substantial body of scholarship in environmental psychology has established that attitudinal and affective orientations toward climate change are among the most consistent predictors of public endorsement of climate policy. Travelers who express worry about global warming, perceive it as an urgent risk, and report affinity toward environmental diversity are more likely to demonstrate stronger support for sustainable tourism, such as conserving energy and preserving local destination environments (

Demirović et al., 2025;

Passfaro et al., 2015;

Sirakaya-Turk et al., 2023). Cross-national research has further corroborated these findings, showing that belief in anthropogenic drivers of climate change and anticipation of severe impacts amplify worry, which in turn fosters approval of ambitious mitigation measures (

Gregersen et al., 2020), even when such measures are politically contentious, such as carbon taxation (

Hasanaj & Stadelmann-Steffen, 2022). In both cases, psychological concern is coupled with emotional response.

Indeed, emotions often predict policy preferences more effectively than demographic or ideological markers (

Smith & Leiserowitz, 2014). For example, negative emotions, such as concern and worry, strengthen public backing for renewable energy development and reduce dependence on fossil fuels (

Lorteau et al., 2024), largely through the intensification of moral commitment (

Böhm et al., 2023;

Myers et al., 2024). Conversely, indifference or skepticism toward climate change, alongside attitudes that prioritize economic expansion over environmental stewardship, are associated with diminished support for mitigation policies (

Haltinner et al., 2021;

Kim & Shin, 2017). These emotional and attitudinal dynamics align with the value-belief-norm (VBN) theory, which posits that the recognition of climate risks coupled with acceptance of moral responsibility functions as a central driver of support for pro-environmental action (

Han et al., 2017;

Stern et al., 1999).

Compared to attitudes and emotions, however, the predictive role of past behavior in shaping climate-policy support is mixed. Some research suggests that individuals who engage in pro-environmental behaviors (e.g., reducing household energy use) are more likely to support broader climate initiatives due to consistency effects and reinforced environmental self-identity (

Bai et al., 2021;

Gatersleben et al., 2014;

van der Werff et al., 2014;

Whitmarsh & O’Neill, 2010). Other studies, however, find that such behavior often adds little explanatory power beyond underlying attitudes and values. In such cases, spillover effects stem more from perceived social norms than from a stable internalized identity (

van der Werff et al., 2014;

Whitmarsh & O’Neill, 2010). This ambiguity is particularly evident in the context of high-emission travel. For instance, low-carbon households may still continue flying for leisure (

Alcock et al., 2017) and express lower support for aviation-specific climate policies despite high levels of environmental concern (

Kantenbacher et al., 2018).

This divergence cautions tourism practitioners that observable travel behavior may be a poor proxy for policy receptivity, as such behavior is often shaped by situational and contextual forces. In contrast, the attitudinal and psychological motivators underlying these behaviors tend to remain more stable across contexts, offering more actionable levers for communication and product design. Accordingly, an integrity-focused lens can connect traveler psychology to concrete tourism policy preferences.

4. Results

4.1. Stage 1: Elastic-Net Regression

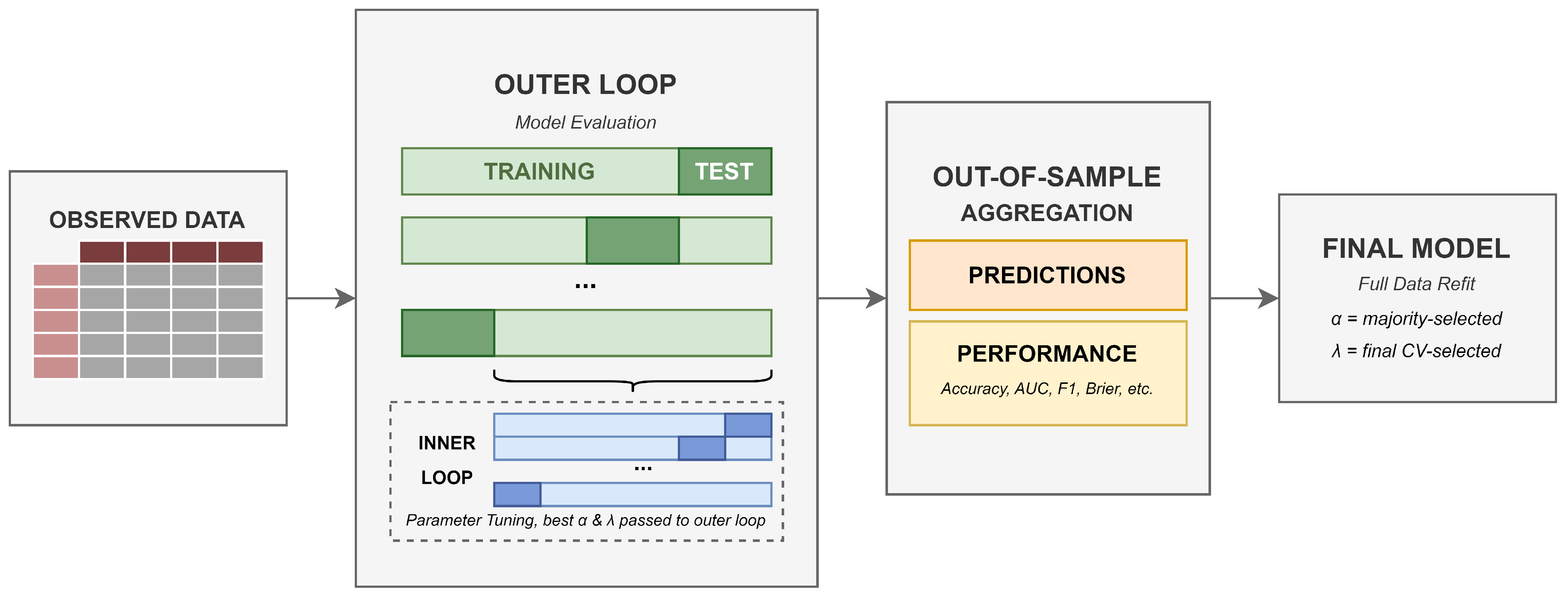

The elastic-net regularized multinomial model (

Zou & Hastie, 2005) identified an optimal penalty balance at

= 0.75, favoring sparsity through a stronger lasso contribution while retaining a modest ridge component for coefficient stabilization. Out-of-sample predictive performance (47.14%) exceeded the majority-class baseline (36.60%) (

Table 2). Although this improvement demonstrates the model’s ability to capture meaningful structure within the data, the modest gain suggested the majority of the variance was unexplained. However, because the model was utilized to identify relative predictor importance, results were interpreted as evidence of weak behavioral separability.

Macro-averaged precision (0.45), recall (0.34), and F1 (0.39) indicated uneven class-level performance, with the Avoidant Non-Flier group recognized with relatively greater fidelity (F1 = 0.60; recall = 0.76), whereas the Avoidant Flier group failed to be detected (recall = 0.00) and the Non-Avoidant Non-Flier group exhibited negligible sensitivity (recall = 0.04). Complementary performance diagnostics suggested moderate discrimination (multiclass AUC = 0.69) but limited calibration (Brier score = 0.64), with probability estimates tending toward underconfidence, as evidenced by observed accuracies exceeding predicted probabilities (e.g., 0.57 vs. 0.54).

Variable shrinkage further revealed no discriminative contribution of several psychological constructs (e.g., Negative, Powerless, Indifferent, Hopeful, No Agency, and Climate Skepticism) and limited contribution of others (e.g., Concern, Responsibility, Confident, and Distribution). In contrast, constructs such as Degrowth and Threat aligned positively with Avoidant profiles, and Growth and Skepticism aligned more strongly with Non-Avoidant profiles. Notably, coefficient structures were largely invariant across Fliers and Non-Fliers within attitudinal categories, suggesting that recent flight behavior (P12M) contributed little explanatory power beyond attitudinal orientation.

The distribution of errors was asymmetric, concentrating within attitudinal categories. In particular, Avoidant Fliers were typically reassigned as Avoidant Non-Fliers, and Non-Avoidant Non-Fliers as Non-Avoidant Fliers. This pattern is consistent with (i) largely invariant coefficient structures for Fliers versus Non-Fliers within a given attitude, (ii) the weak incremental contribution of recent flight behavior over the P12M, and (iii) near-chance discrimination when predicting Flier versus Non-Flier within attitude ( = 0.596; = 0.518). Collapsing the outcome to a binary Avoidant versus Non-Avoidant target improved accuracy to 67.97% ( = 0.758), and the four-class model’s Top-2 accuracy reached 75.56%, indicating that most errors arose within, rather than across, attitudinal boundaries.

Combined with the uneven class-level performance and improved accuracy when outcomes were collapsed to attitudinal groups, the modeling results indicate stronger differentiation by attitudes and limited predictive value for recent flight behavior.

4.2. Stage 2: Factorial ANCOVA Outcomes

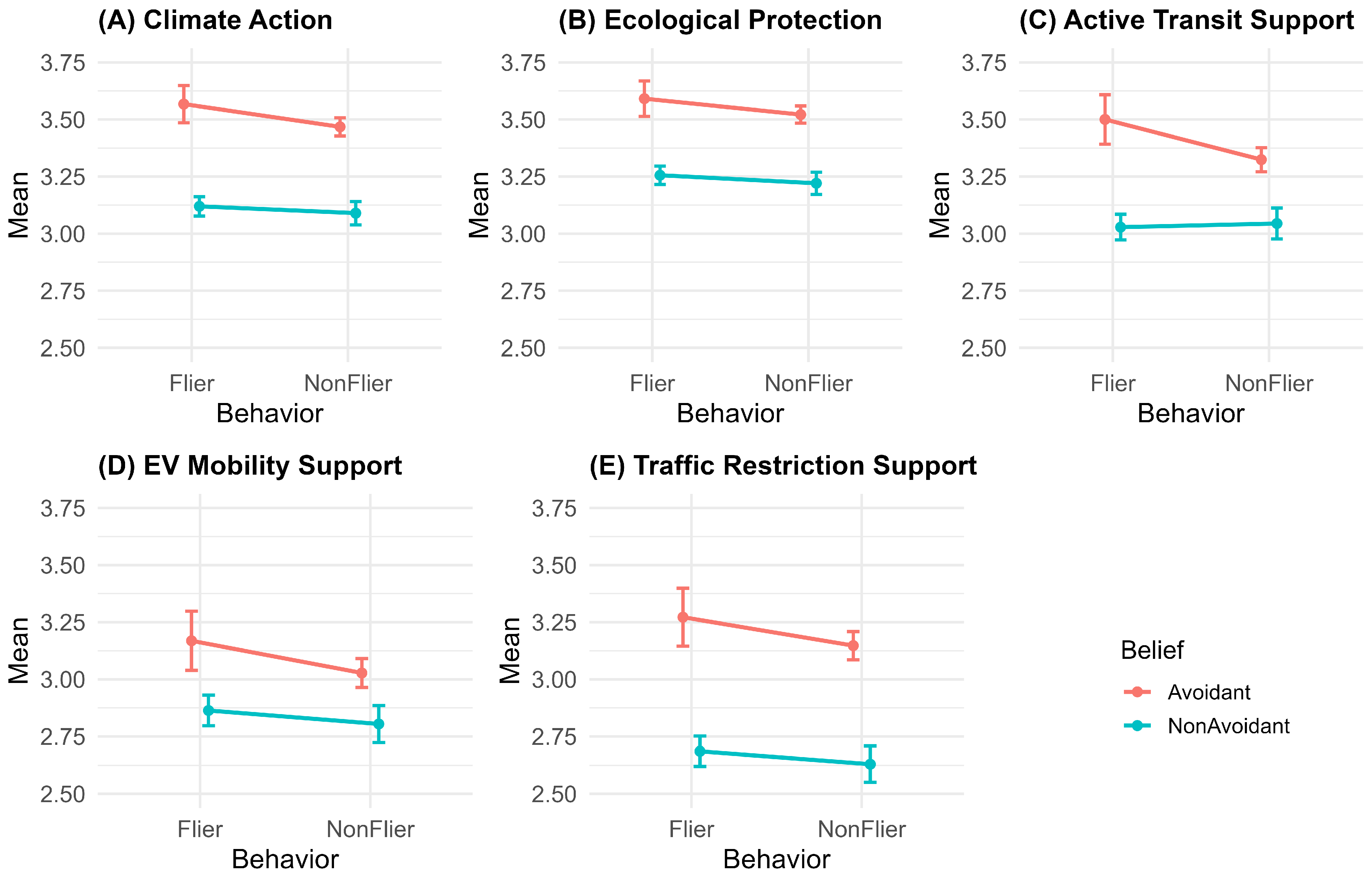

A multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) with gender, age, college education, full-time employment status, and income serving as control covariates showed a significant omnibus effect indicating a difference between the four travel groups across the set of five policy support outcomes, Pillai’s trace = 0.142, F(15, 5520) = 18.29,

p < 0.001. Given the significant omnibus effect, separate 2 (Avoidant vs. Non-Avoidant) × 2 (P12M Flier vs. Non-Flier) factorial ANCOVAs were conducted on each of the five dependent variables to determine the specific dimensions of policy support on which the travel groups differed (

Figure 2).

Across all outcome variables, there was a main effect of Avoidant vs. Non-Avoidant flying (see

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7; all

p < 0.001, partial

from 0.018 to 0.101), with flight Avoidant respondents reporting significantly higher endorsement of environmental and climate change policy support than their Non-Avoidant counterparts. In contrast, P12M Flier vs. Non-Flier yielded much smaller main effects that were nonsignificant to marginally significant, with small effect sizes (see

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7;

p from 0.027 to 0.058, partial

from 0.002 to 0.003), with the P12M Fliers being slightly more supportive of environmental and climate change policies than their Non-Flier counterparts. A significant interaction effect between Flight Avoidance and P12M Flight Behavior was only significant for the Active Transit Support outcome variable, albeit with a very small effect size (

p = 0.010, partial

= 0.004). There was no interaction effect for all other variables (

p from 0.215 to 0.521).

4.3. Supplemental Results

The binary measure of flight behavior used in the main analyses did not capture variability in travel patterns, such as the frequency or duration of flights. To incorporate this additional nuance, a “flight index score” was developed. Respondents reported how often they took short (<2 h), medium (2–4 h), and long (>4 h) flights. These frequencies were multiplied by a weight of 1 (short), 2 (medium), and 3 (long) to account for differences in flight duration and summed to produce a quasi-continuous index. Supplemental analyses using the flight index produced results that were consistent with those obtained with the binary classification, indicating that the additional granularity did not materially affect the findings (see

Supplemental Tables S1–S5). An additional sensitivity analysis using alternative weights of 1, 3, and 6 for short-, medium-, and long-haul flights yielded substantively identical results (see

Supplemental Tables S6–S10).

An additional supplemental analysis examined whether the perceived importance of traveling and exploring differed across the four flight profiles (

Supplemental Table S11). The results indicated significant main effects of flight-avoidant value, F(1, 2400) = 97.02,

p < 0.001, partial

= 0.051, and flight behavior, F(1, 2400) = 87.72,

p < 0.001, partial

= 0.046. Specifically, respondents who did not avoid flying for environmental reasons and those who had flown in the past 12 months reported that traveling was more important to them. However, the interaction between flight-avoidant value and flight behavior was not significant, F(1, 2400) = 1.17,

p = 0.280, partial

= 0.001.

Given the notable differences in the subjective importance of traveling between those who had and had not flown, respondents were further classified based on their reported affinity toward traveling. Individuals expressing a positive affinity were categorized as “Travelers,” while those reporting little to no affinity were categorized as “Non-Travelers.” This classification was introduced as a third factor in a 2 × 2 × 2 factorial ANCOVA to examine potential interactions between travel affinity, flight-avoidant value, and flight behavior (see

Supplemental Tables S12–S16). However, no significant interactions involving travel affinity were observed across all outcome variables,

p from 0.055 to 0.830.

5. Discussion

The present study examined the attitudinal factors underlying flight avoidance and flying behavior and assessed how these dimensions may interact to influence subsequent support for environmental policy. Results from both machine learning and inferential analyses revealed that individuals expressing normative opposition to flying for environmental reasons (i.e., flight-avoidant respondents) consistently reported stronger support for climate and environmental policy measures. Notably, this association held irrespective of whether respondents had engaged in personal air travel within the P12M. By contrast, P12M flight behavior exhibited only trivial associations with policy support and did not significantly moderate the influence of flight-avoidance attitudes. Further, the absence of significant interactions suggests that flight avoidance attitudes exert largely independent effects on policy support from behavior, reinforcing the dominance of attitudinal over behavioral factors.

These findings align with prior research demonstrating that internalized norms, environmental values, and identity, as opposed to behavioral purity, serve as the more central predictors of environmental concern and policy endorsement (

Berneiser et al., 2022;

van der Werff et al., 2014). Within the aviation domain, this pattern echoes past evidence that pro-environmental attitudes frequently correspond with sustainable household practices but rarely translate into reductions in discretionary air travel (

Alcock et al., 2017;

Árnadóttir et al., 2021;

Kroesen, 2013). These results suggest that environmental identity may constitute a psychologically foundational determinant of policy support, outweighing the influence of strict behavioral adherence. That is, identity functions as a cognitive-motivational foundation that enhances acceptance of structural measures rather than as a substitute for them.

More unexpectedly, individuals who reported air travel within the P12M expressed marginally higher support for climate policy than their non-flying counterparts. Although the effect size was small, this counterintuitive result may be attributable to compensatory psychological mechanisms (

Oswald & Ernst, 2020;

Pratt & Tolkach, 2023;

Schrems & Upham, 2020). Cognitive dissonance theory suggests that individuals confronting the tension between high-emission behaviors and pro-climate values may reduce dissonance by reinforcing adjacent commitments, such as endorsing ambitious environmental policies (

Árnadóttir et al., 2021;

Schrems & Upham, 2020). A second explanation centers on socioeconomic privilege. That is, frequent flyers are disproportionately likely to possess higher levels of education, income, and cosmopolitan outlook, all of which are consistently linked to greater environmental awareness and policy support (

Fisher & LaMondia, 2024;

Oswald & Ernst, 2020). On the other hand, results should also be interpreted in light of the broader post-COVID rebound in leisure mobility, which temporarily amplified travel demand irrespective of environmental attitudes and may have attenuated observed behavioral integrity.

The infrastructural context of Germany and its neighboring regions is also likely to have influenced the present findings. Many of Germany’s most frequently visited foreign destinations (e.g., Spain, Greece, Turkey) commonly require air travel owing to geographical distance or logistical constraints. For example, although travel within the EU or Schengen area is administratively streamlined, journeys to the Balearic or Canary Islands typically necessitate flying, as overland and maritime alternatives are disproportionately unduly complex and impractical for lower to middle-socioeconomic groups. Likewise, non-European destinations (e.g., Egypt, the United States) are effectively inaccessible without air travel. Such structural limitations are barriers to norm-consistent travel behavior across European contexts (

Hepting et al., 2020) and reinforce that behavioral non-alignment may stem as much from infrastructural and systemic limitations (

Árnadóttir et al., 2021;

Berneiser et al., 2022).

5.1. Behavioral Integrity as Context-Dependent

Although behavioral integrity is often examined at the individual level, where misalignments between values and actions are attributed to personal dispositions or volitional choice, this perspective can obscure the structural and situational conditions that shape behavioral feasibility. Socioeconomic circumstances, geographic location, and other infrastructural constraints can substantially limit the practicability of aligning behavior with environmental values. For instance, long-distance leisure travel is frequently only practical via air transport due to geographic and logistical constraints. Moreover, although the expansion of budget airlines has increased accessibility for broader socioeconomic groups, the overall expenses associated with leisure travel (e.g., accommodation, local transportation, activities, opportunity costs of time) are likely to remain significant obstacles for lower-income groups.

Recognizing this distinction carries important implications for how integrity is assessed in environmental and sustainability research. Many existing approaches implicitly assume that individuals possess the freedom and resources to act in accordance with their values. When this assumption is not met, constrained behaviors may be misinterpreted as a lack of commitment (

Gifford, 2011;

Steg et al., 2014). Overlooking the influence of structural barriers risks systematically underestimating genuine normative commitment, particularly among those operating in the most restrictive contexts.

Distinguishing between constrained and unconstrained circumstances may yield a more accurate and context-sensitive approach to investigating how individuals maintain, negotiate, or adapt their integrity when structural barriers impede value-consistent action. Such an approach can offer practical guidance for designing interventions that support integrity-enhancing behaviors in settings where options are limited, while also providing a more precise conceptual understanding of integrity grounded in the lived conditions that shape environmental decision-making (

Hansmann & Binder, 2021;

Thøgersen, 2014).

5.2. Implications for Tourism and Hospitality

Guided by findings demonstrating that attitudinal factors more robustly predicted policy support whereas recent flying behavior contributed minimal explanatory value, tourism and hospitality initiatives may benefit from prioritizing attitudinal segmentation over behavioral proxies when assessing climate or environmental support sentiment. In practice, this entails orienting customer insight efforts toward understanding how travelers perceive and emotionally engage with sustainability, and leveraging these insights to tailor message framing, loyalty incentives, and product positioning. In contrast, observable flight behavior may serve as a less stable or less reliable indicator of receptivity to climate action, potentially due to contextual or infrastructural limitations that constrain behavioral expression.

Consistent with prior research indicating that pro-sustainability values and environmental awareness are stronger predictors of sustainable travel intentions than past behavior alone (

Ma et al., 2024), supplementary analyses from the present study suggest that those exhibiting a strong inclination toward travel will do so regardless of their sustainability orientations. Conversely, non-fliers may claim to avoid air travel out of environmental concern, though such abstention may instead be attributed to limited interest in travel or other situational constraints. In other words, environmental reasoning may serve as a socially desirable justification aligned with prevailing normative expectations. Practitioners should therefore interpret self-reported environmental motives with caution and integrate attitudinal data with contextual insights concerning travelers’ actual mobility options.

The finding that air travel remains prevalent even among sustainability-oriented individuals implies the presence of structural or practical barriers that hinder the feasibility of adopting low-carbon travel alternatives. Enhancing the accessibility and convenience of such alternatives relative to air travel (e.g., expanding train or intercity coach services) may increase the likelihood that environmentally conscious travelers align their behaviors with their values (

Janchai & Suvittawat, 2025;

Laachach & Alhemimah, 2024). This dynamic presents immediate opportunities for practitioners and policymakers to develop and promote visible low-carbon options while communicating transparent emissions performances. Such initiatives may have the potential to facilitate the translation of positive environmental attitudes into concrete behavioral change, preserving tourism demand and creating competitive advantages for organizations that position themselves at the forefront of travel decarbonization.

5.3. Limitations

Given the cross-sectional design, the causal directionality of our findings is not definitive and remains conceptual. Experimental or quasi-experimental designs can yield stronger causal inferences. Second, the study relies on self-reported data and may be subject to recall error or social desirability bias. These concerns are particularly salient for flight activity and environmental attitudes, which are likely influenced by prevailing social norms. Third, although the robustness check using the weighted flight index provides a more fine-grained account of air travel behavior, the index does not capture the nuances underlying travel decisions, such as whether the personal flights were discretionary (e.g., vacation) or obligatory (e.g., attending a funeral). Indeed, although the absence of significant interaction effects lends interpretive clarity to the role of normative identity, it also highlights potential constraints in the behavioral measurement itself. Future research can distinguish between discretionary and obligatory personal travel (e.g., vacations versus family emergencies) and employ qualitative methods such as focus groups or semi-structured interviews to explore how travelers justify continued support for sustainability initiatives when their actions diverge from their values. Lastly, the present findings are situated within the sociocultural and infrastructural context of Germany, a country characterized by relatively high levels of environmental concern, well-developed rail infrastructure, and frequent international travel. Generalizations to other national contexts should therefore be made with caution.